Communism and Anti-Communist Dissent in Romania as Reflected in Contemporary Textbooks

Abstract

“History makes fools of those who do not know it, by repeating itself.”Nicolae Iorga(Romanian Historian, 1871–1940)

1. Introduction

2. Literature

3. Conceptual Framework

4. Methodology

5. Results and Discussion

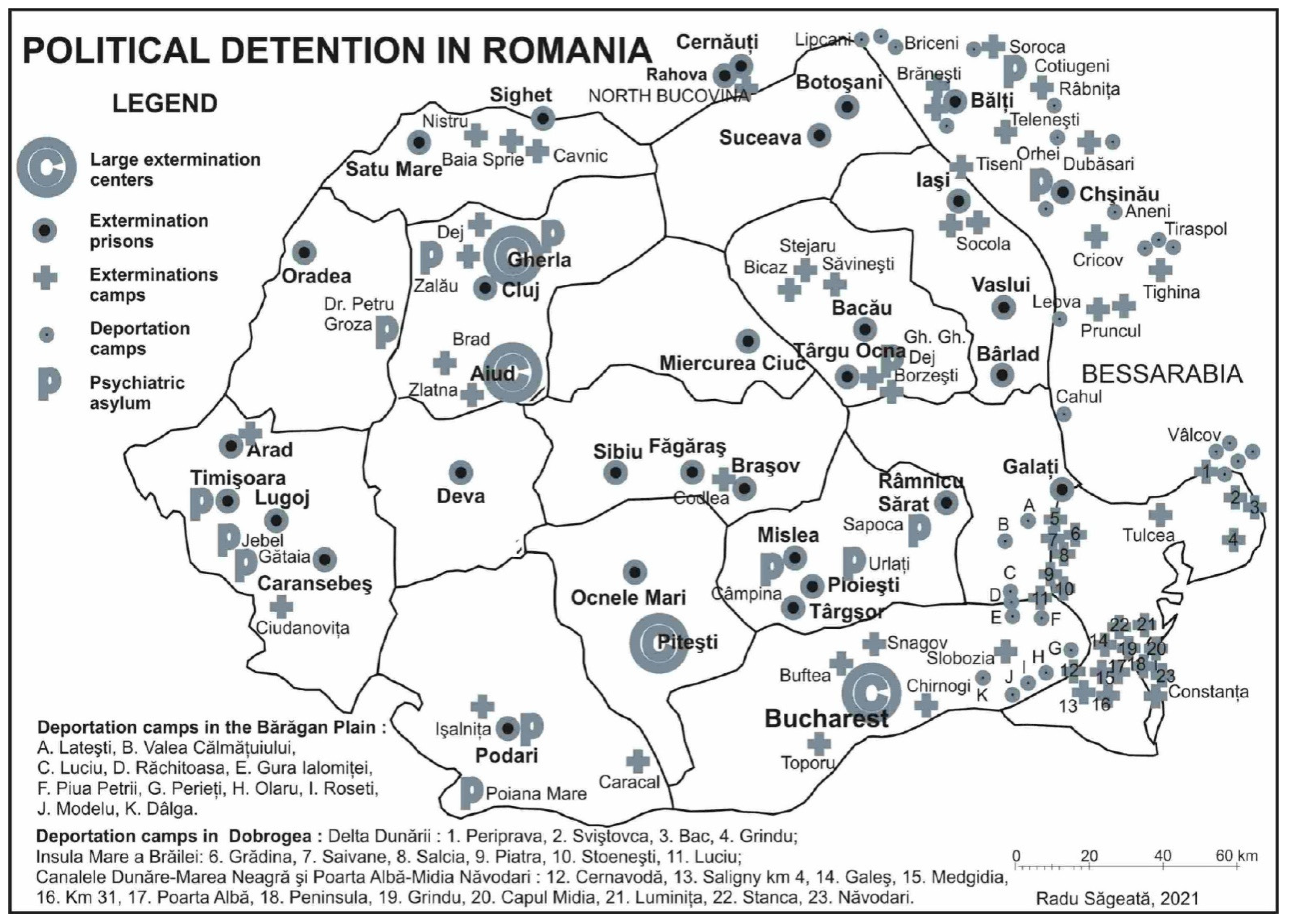

5.1. The Suppression of Public Rights and Freedoms, Censorship and Repression or … “It Used to Be Worse”

5.2. Communism as a Motor Factor of Economic and Social Development or … “It Used to Be Better”. From Information in Textbooks to the Emotional Stories of Nostalgic Parents and Grandparents

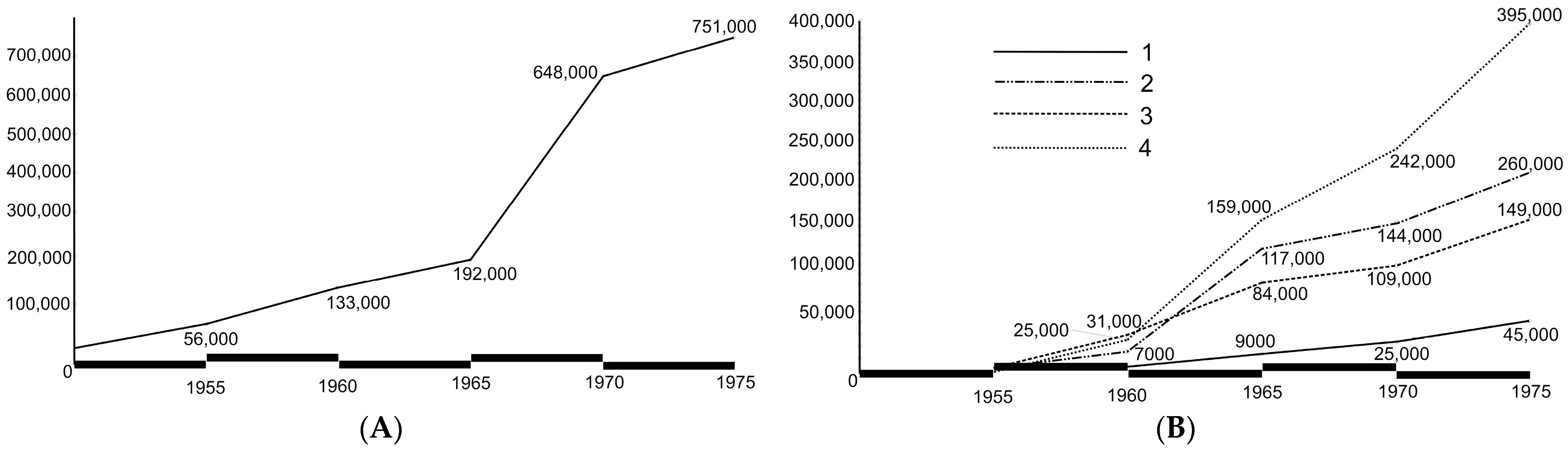

5.2.1. Industrialization and Urbanization as a “Response” to the Valev Plan. Nationalist Communism and Its Social Consequences

5.2.2. Romanian Society under Communist Totalitarianism. Repression Versus Obedience and Adaptation

5.3. The Young Generation’s Perception of Communism between “It Used to Be Worse” and “It Used to Be Better”

5.3.1. The Quality of Education in Romania. How We Begin the Analysis

- -

- A lack of adapting to changes in society. In the current technological conditions and the influx of information through various media sources, learning is no longer limited to how much one can assimilate, but to what one assimilates, to how one extracts knowledge from the multitude of information one can obtain. A. Schleicher, director of education of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, believed, in this regard, that “in the 20th century, democracy had to do with the right of being equal to others; in the 21st century, democracy has to do with the right of being different. We must understand that students need to learn differently” (Schleicher, quoted by [52]);

- -

- A lack of equity in Romanian schools. There are very big differences in how students perform in different schools, which stems from unequal development (rural–urban, disadvantaged regions and social environments, areas of endemic poverty, etc.);

- -

- A lack of satisfaction with the educational process, both in the case of students, as well as teachers. Students learn strictly in order to achieve good grades, and teachers teach strictly related to their subject. Romania needs high-calibre teachers, leaders who also constantly learn and collaborate with students. The Romanian educational system, developed in the 1960s and 1970s, under the thumb of communist totalitarianism, has made not enough progress in this regard.

- -

- Chronic underfunding. An analysis at the European level highlights the fact that the Romanian education system is the least funded in the EU, benefitting from just 3.1% of GDP in 2020, a percentage that decreased in 2021 to only 2.5% of GDP, compared to 7.8% of GDP in Denmark or 7.6% in Sweden. In comparison, Bulgaria assigns 4.1% of GDP to education, and Hungary 4.7% [53].

5.3.2. The Young Generation’s Perception of Communism as Reflected in Several Polls

- What are, in your opinion, the three main characteristics of communism?

- How do you appreciate the influence of communism on contemporary Romanian society?

- What do you think about communism?

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Dunca, A. Education and post-communist transitional justice: Negotiating the communist past in a memorial museum. Southeast Eur. Black Sea Stud. 2019, 19, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurtu, I.; Dondorici, F.; Ionescu, V.; Lica, E.-E.; Osanu, O.; Poamă, E.; Stoica, R. Istorie. Manual Pentru Clasa a XII-a [History. School Book for the 12th Grade]; Gimnasium Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2007; 151p. [Google Scholar]

- Stoica, S.; Băluţoiu, V.; Becheru, D.-S.; Bilcea, V.; Bondar, A.; Grecu, M. Istorie. Manual Pentru Clasa a VIII-a [History. School Book for the 8th Grade]; CD Press Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2020; 135p. [Google Scholar]

- Soare, A.-C.; Cojocaru, D.-A.; Grozav, G.; Pavelescu, A. Istorie. Manual Pentru Clasa a VIII-a [History. School book for the 8th Grade]; Art Klett Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2020; 120p. [Google Scholar]

- Le Breton, J.-M. L’Europe Centrale et Orientale de 1917 à 1990 [Central and Eastern Europe from 1917 to 1990]; Nathan, Paris, France, 1994 & Cavaliotti Publishing Houses: Bucharest, Romania, 1996; 306p. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, S.; Budeancă, C. (Eds.) Countryside and Communism in Eastern Europe. Perceptions, Attitudes, Propagandas; LIT Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2016; 672p. [Google Scholar]

- Naimark, N.; Pons, S.; Quinn-Judge, S. (Eds.) The Cambridge History of Communism, Volume II: The Socialist Camp and World Power, 1941–1960; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; 684p. [Google Scholar]

- Hassner, P. Beyond History and Memory. In Stalinism and Nazism. History and Memory Compared; Rousso, H., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2004; pp. 283–295. [Google Scholar]

- Laignel-Lavastine, A. Fascism and Communism in Romania: The Comparative Stakes and Uses. In Stalinism and Nazism. History and Memory Compared; Rousso, H., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2004; pp. 157–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, G. Communism in Romania 1944–1962; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1964; 378p. [Google Scholar]

- Shafir, M. Romania: Politics, Economics and Society: Political Stagnation and Stimulated Change; Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA; Frances Pinter: London, UK, 1985; 232p. [Google Scholar]

- Shafir, M. România comunistă (1948–1985). O analiză politică, economică şi socială [Communist Romania (1948–1985). A Political, Economic and Social Analysis]; Meteor Press: Bucuresti, Romania, 2021; 432p. [Google Scholar]

- Tismăneanu, V. Arheologia terorii [Archeology of Terror]; Curtea Veche Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2008; 195p. [Google Scholar]

- Deletant, D. Ceauşescu and the Securitate. Coercion and Dissent in Romania 1965–1989; Routledge: London, UK, 1995; 456p. [Google Scholar]

- Deletant, D. România sub regimul comunist [Romania under Communist Rule]; Civic Academy Foundation: Bucharest, Romania, 2006; 294p. [Google Scholar]

- Deletant, D. Communist Terror in Romania Gheorghiu Dej and the Police State 1948–1965; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2000; 351p. [Google Scholar]

- Troncotă, T. România comunistă. Propagandă şi cenzură [Communist Romania. Propaganda and Censorship]; Tritonic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2006; 224p. [Google Scholar]

- Denize, E. Propaganda comunistă în România (1948–1953) [Communist Propaganda in Romania (1948–1953)], 2nd ed.; Cetatea de Scaun Publishing House: Suceava, Romania, 2011; 400p. [Google Scholar]

- Gherasim, G.-T. România: Martiri şi supravieţuitori din comunism [Romania: Martyrs and Survivors of Communism]; Libris Editorial Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2018; 172p. [Google Scholar]

- Corobca, L. (Ed.) Panorama comunismului în România [Panorama of Communism in Romania]; Polirom Publishing House: Iaşi, Romania, 2021; 1152p. [Google Scholar]

- Betea, L. Ceauşescu şi epoca sa [Ceauşescu and His Time]; Corint Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2021; 848p. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, A. Europe’s Divided Memory. In Clashes in European Memory: The Case of Communism Repression and the Holocaust; Blaive, M., Gerbel, C., Thomas, L., Eds.; Studien Verlag: Innsbruck, Austria, 2011; pp. 270–280. [Google Scholar]

- Brunnbauer, U. Remembering Communism During and after Communism. Contemp. Eur. Hist. 2012, 21, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Macdonald, S. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; 320p. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, M. Communism, Youth and Generation. In The Cambridge History of Communism; Pons, S., Smith, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 475–502. [Google Scholar]

- Mrozik, A.; Holubec, S. (Eds.) Historical Memory of Central and East European Communism; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; 294p. [Google Scholar]

- Creţan, R.; Light, D.; Richards, S.; Dunca, A. Encountering the victims of Romanian communism: Young people and empathy in a memorial museum. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2018, 59, 632–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohrib, C.-A. The Romanian “Latchkey Generation” writes back: Memory genres of post-communism on Facebook. Mem. Stud. 2019, 12, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Young, C. Habit, Memory, and the Persistence of Socialist—Era Street Names in Post-socialist Bucharest, Romania. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2014, 104, 668–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artwińska, A.; Mrozik, A. (Eds.) Gender, Generations, and Communism in Central and Eastern Europe and Beyond; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Stan, M. Istoria ilustrată a românilor pentru elevi [The Illustrated History of Romanians for Students]; Litera Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2018; 111p. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, I.-A. Istoria ilustrată a românilor pentru tineri [The Illustrated History of Romanians for Young People]; Litera Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2018; 238p. [Google Scholar]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Dunca, A. Museums and transitional justice: Assessing the impact of a memorial museum on young people in post-communist Romania. Societies 2021, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Dunca, A. Transitional justice and the political ‘work’ of domestic tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdeli, G.; Cândea, M.; Braghină, C.; Costachie, S.; Zamfir, D. Dicţionar de Geografie Umană [Dictionary of Human Geography]; Corint Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1999; 391p. [Google Scholar]

- Serebrian, O. Dicţionar de Geopolitică [Dictionary of Geopolitics]; Polirom Publishing House: Iaşi, Romania, 2006; 339p. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, L. (Ed.) Oxford. Dicţionar de Politică [The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics]; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996; Univers Enciclopedic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2001; 526p. [Google Scholar]

- Zamfir, C.; Vlăsceanu, L. Dicţionar de sociologie urmat de indicatori demografici, economici, sociali şi sociologici [Dictionary of Sociology Followed by Demographic, Economic, Social and Sociological Indicators]; Babel Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1993; 769p. [Google Scholar]

- Stoica, S.; Becheru, D.-S. Istorie. Manual pentru clasa a VII-a [History. School Book for the 7th Grade]; CD Press Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2019; 95p. [Google Scholar]

- Coteanu, I. Micul dicţionar academic [The Little Academic Dictionary], IV-ed.; Univers Enciclopedic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2003; 1408p. [Google Scholar]

- Petre, Z.; Căpiţă, C.; Stănescu, E.; Lung, E.; Livadă-Cadeschi, L.; Ciupală, A.; Ţurcanu, F.; Vlad, L.; Andreescu, S. Istorie. Manual pentru clasa a XII-a [History. School Book for the 12th Grade]; Corint Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2008; 160p. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, A.; Manea, V.-A.; Palade, E.; Teodorescu, B. Istorie. Manual pentru clasa a XII-a [History. School Book for the 12th Grade]; Corint Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2007; 128p. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, A. Peste 30,000 de români au fost ucişi de comunişti la Canalul Dunăre—Marea Neagră [Over 30,000 Romanians were Killed by Communists while Working on the Danube Canal—Black Sea]. Acad. Caţavencu 2009, 24. Available online: http://www.asapteadimensiune.ro/file-d (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- The Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and the Memory of the Romanian Exile. Politics of Memory in Post-communist Europe; Zeta Books: Bucharest, Romania, 2020; Volume I, 298p. [Google Scholar]

- Vesalon, L.; Creţan, R. Monoindustrialism and the struggle for alternative development: The case of Roşia Montană project. Tijdschr. voor Economischeen Soc. Geogr. 2013, 104, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Văran, C.; Creţan, R. Place and the spatial politics of intergenerational remembrance on the Iron Gate displacements 1966–1972. Area 2018, 50, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A.; Manea, V.; Palade, E.; Petrescu, F.; Teodorecu, B. Istorie. Manual pentru clasa a XI-a [History. School Book for the 11th Grade]; Corint Educaţional Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2014; 128p. [Google Scholar]

- Ciupercă, I.; Cozma, E. Istorie. Manual pentru clasa a XI-a [History. School Book for the 11th Grade]; Corint Educaţional Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2014; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Guvernul României [Government of Romania]. Calitatea în învăţământul românesc actual [Quality in Current Romanian Education]; Guvernul României: Bucharest, Romania, 2020. Available online: https://eduform.snsh.ro (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Peticilă, M. Generația 2009–2021. Aproape 204,000 de elevi înscrişi în clasa I acum 12 ani, doar 152 000 au ajuns la finalul liceului/Au avut 17 miniștri ai Educației [Generation 2009-2021. Almost 204,000 Students Enrolled in the First Grade 12 Years Ago, Only 152,000 Reached the End of High School/They had 17 Ministers of Education]; EduPedu.ro: Bucharest, Romania, 2021; Available online: https://www.edupedu.ro/generatia-2009-2021-aproape-204-000-de-elevi-inscrisi-in-clasa-i-acum-12-ani-doar-152-000-au-ajuns-la-finalul-liceului/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Ministry of Nation Education, Bucharest, Romania. Available online: https://www.newsmaker.ro (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Ionescu, C. Învăţământul românesc, văzut prin ochi internaţionali. O descriere nemiloasă de la șeful educaţiei OECD: Ce fac sistemele cele mai performante ale lumii, iar în România se face mai mult pe hârtie [Romanian Education, Seen through International Eyes. A Ruthless Description from the Head of Education OCDE: What Do the Best Performing Systems in the World Do, and in Romania More is Done on Paper]. Bucharest, 2020. Available online: https://www.edupedu.ro/invatamantul-romanesc-vazut-prin-ochi-internationali-o-descriere-nemiloasa-de-la-seful-educatiei-oecd-ce-fac-sistemele-cele-mai-performante-iar-in-romania-se-face-cel-mult-pe-hartie/ (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- The World Bank. Government Expenditure on Education (% of GDP). UNESCO Institute of Statistics: Paris, France, September 2020. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.XPD.TOTL.GD.ZS (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Deutsche Welle. Tinerii şi provocarea trecutului [Youth and the Challenge of the Past]. 2011. Available online: https://p.dw.com/p/10sJU (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- The Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and the Memory of the Romanian Exile; The Centre for Opinion and Market Studies. Percepţia actuală asupra comunismului [The Current Perception of Communism]. Bucharest, 2013. Available online: https://www.crimelecomunismului.ro (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Soare, A. Ce părere au tinerii despre Nicolae Ceauşescu şi cum văd aceştia comunismul [What do Young People Think About Nicolae Ceauşescu and How They See Communism]. 2017. Available online: https://editiadedimineata.ro/ce-parere-au-tinerii-despre-nicolae-ceausescu-si-cum-vad-acestia-comunismul/ (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Pew Research Centre. End of Communism Cheered but Now with More Reservations. 2 November 2009. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2009/11/02/end-of-communism-cheered-but-now-with-more-reservations/ (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Bujoreanu, S. Cum au răspuns mai mulţi tineri între 19 şi 22 de ani la 6 întrebări esenţiale despre comunism [How Did Several Young People between the Ages of 19 and 22 Answer 6 Essential Questions about Communism]. 2019. Available online: https://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-esential-23561292-stiu-tinerii-despre-comunism.htm (accessed on 18 August 2021).

| Year of Reference | The Perception on Communism in Romania (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Good Idea, Correctly Implemented | Good Idea, Poorly Implemented | Bad Idea | |

| 2009 | 12 | 41 | 34 |

| 2013 | 14 | 47 | 27 |

| Subject Data | Answers to Questions | General Opinion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/W | Age | Occupation | A:Q1 | A:Q2 | A:Q3 | A:Q4 | |

| M | 22 | Sociology Student | The parents’ experience | The Police, restrictions in place | The international context | Repressive, stupid, but reformative | Unfavourable |

| W | 22 | Manager’s Assistant | Hard times, queuing, rationing | The lack of access to information | For fear of the authorities, the citizen’s resignation | He rationed food, developed the economy and infrastructure | Unfavourable |

| W | 18 | Highschool Student | Queuing, shortages | The outlawing of abortions | The people’s mentality | He changed the educational system, he passed harsh laws | Unfavourable |

| W | 19 | Law Student | Pain, repression | The perversion of values | The lack of unity to effect change | The main representation of all horrors | Unfavourable |

| M | 19 | Economics Student | Dark times which impact present-day mentalities | The mentality born during that time | The lack of international involvement | He did both good and bad things | Neutral |

| W | 19 | Highschool Graduate | Repression | Unquestionable obedience | The fear | Was not a good president, because he acted against the citizens | Unfavourable |

| M | 19 | Sociology Student | Food and electricity shortages | Censorship and the repressive system | In the beginning, the system worked | He was inspired by the cult of personality, he exported everything the country produced | Unfavourable |

| Subject Data | The Main Characteristics of Communism and of Nicolae Ceauşescu according to the Interviewed Subject | General Opinion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/W | Age | Occupation | ||

| M | 20 | Law Student | There are no reasons for communism nostalgia. It was a difficult time, of lies and shortcomings. The cities were demolished, history was distorted. The urban physiognomy was destroyed. | Unfavourable |

| W | 19 | Psychology Student | The communist regime wished to promote freedom, but the opposite happened. Everything worked on the basis of who-knows-who, which still has consequences in the population’s way of thinking. | Unfavourable |

| M | 21 | Geography Student | Romania was governed by the Russians, Ceauşescu was a puppet. Young intellectuals were imprisoned and beaten, even imprisoned, and killed in camps. Man must be free, think freely and express himself freely. | Unfavourable |

| W | 23 | Coventry University Graduate | They are not nostalgic for communism. There was censorship, TV broadcast was limited and propaganda-based. There were frequent power outages. Everyone had a job, work was mandatory. There were food shortages, queues were a common occurrence. | Unfavourable |

| M | 21 | Psychology Student | Ceauşescu was a typical example of the average Romanian: mediocre intellectual abilities, displayed a tendency to assert himself, had ambitions, pride, megalomania, was easily influenced. The communist regime was based on an oversized economy, a chaotic use of resources, fear, all sorts of shortages, stable employment, and services. | Unfavourable |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Săgeată, R.; Damian, N.; Mitrică, B. Communism and Anti-Communist Dissent in Romania as Reflected in Contemporary Textbooks. Societies 2021, 11, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040140

Săgeată R, Damian N, Mitrică B. Communism and Anti-Communist Dissent in Romania as Reflected in Contemporary Textbooks. Societies. 2021; 11(4):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040140

Chicago/Turabian StyleSăgeată, Radu, Nicoleta Damian, and Bianca Mitrică. 2021. "Communism and Anti-Communist Dissent in Romania as Reflected in Contemporary Textbooks" Societies 11, no. 4: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040140

APA StyleSăgeată, R., Damian, N., & Mitrică, B. (2021). Communism and Anti-Communist Dissent in Romania as Reflected in Contemporary Textbooks. Societies, 11(4), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040140