Jogging during the Lockdown: Changes in the Regimes of Kinesthetic Morality and Urban Emotional Geography in NW Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. COVID-19 Pandemic and the Experience of Urban Space

1.2. Jogging and the Experience of Urban Space

1.3. Jogging and COVID-19 in Italy

1.4. The Study Location

1.5. Objectives

- How did COVID-19 change the livability of the city?;

- How did the lockdown change the meaning of a cultural physical practices in an urban environment?;

- How did the lockdown change the understanding of the city environment among the joggers?; and

- How did the clash between opposing kinesthetic moralities develop for the joggers?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Role of Jogging

“For me, jogging means freedom. It allows me to undress from my everyday life. I take off my jacket and my tie and put on one of those absurd sports shirts. No cell phone. No wallet. I jump on the street and am alone with my thoughts. I listen to the noises of the city and the countryside. It’s hard to say in words, but that’s why I love to jog every day. It’s my salvation or at least it was before the COVID [pandemic]. Before the lockdown I always felt free when I jogged. Then it became different… the very city was different… and I found I was asking myself ‘Am I wrong? Am I the enemy of the people? Or is it the city turned into a hostile place?’”

“I started jogging five or six years ago when I changed jobs. Before I worked in a shop and with shifts, I managed to go to the swimming pool most days. Since I started working in the restaurant sector I started commuting to [a nearby town]. There is no swimming pool there and I could not put the times together to go every day to the swimming pool in Alessandria. So, I decided to start running every day. For better or for worse, I manage to go running every day in the morning, one hour. It makes me feel good and I don’t have big-time problems.”

“I started jogging twenty years ago. I was twenty-five or so. From jogging then I started to participate in some non-competitive races, such as Stralessandria. Jogging is my way to relax after a day in the office. Taking part in these competitions amuses me because I team up with friends. To meet with friends for running is important. Every week, before the pandemic, on Saturday afternoons, I and other friends went for a run. Sometimes just outside the city, we took the car and went to some new places in the countryside. For me, at the end of the day, jogging is to live the space of the city and the countryside and share emotions with the people who run with me.”

“I started jogging a few years ago; it must have been 2015. […] It is often the only real physical activity I do […]. I work in an office: hours in front of the computer. The most I walk is from home to the garage and from the parking lot to the office. I need to run; it’s freedom and well-being for me. Before, Alessandria was for me just the street from home to work and another bunch of places and shops. Since I have started jogging, I have known new places, such as the hamlets around the city, or the hills just beyond the river. I also met new people who jog like me every day on the embankments.”

“My wife and I are both professionals and, in the evening, when we are back from the office, we go for a run in the countryside. We both run. It is something we do mostly two or three times a week and it is our way to escape from the city and it makes us feel good.”

3.2. The Experience of the Lockdown

“I usually run at 6.00/6.30 AM. If I meet someone it is some animal or possibly someone from my condominium (I live in a condominium). March and April were tough. Even before the most stringent obligations, people have changed. It didn’t matter if I had a mask or whatever. For the first time, I realized that people were looking at me. A neighbor, one day, started shouting at me from the balcony: “Bastard! You want to kill us all!” The thing repeated for some days. Then, I started going to run earlier; at 5.00, in order not to meet anyone, but still, I did not feel safe. I felt like they had put me in a cage. In the end, I bought a treadmill and for almost a month I didn’t put my nose out of the flat.”

“My jogger quarantine experience? A bucket of cold water at the beginning of March. I don’t speak metaphorically. It was still more or less allowed to go for a run. I leave the house to do my usual run. I go under various condominiums and shops. I usually go around 7.00 in the morning and it’s not like there are all these people. Well … I was running and: “splash!”. From the second floor, a man threw a bucket of water over me. I almost had a heart attack. Was it a joke? No. He shouted at me: “You should be ashamed running these days! Stay at home!” I didn’t do anything. I didn’t say anything. I left, running. What could I do? Should I denounce him? For what? After that day, I hung up the boots. Once and for all after that episode. Well, more or less. Sometimes I got up before dawn and went around a few blocks … but I felt I was moving in a hostile landscape; not because of the virus. Because of the people around me.”

“It was a horrible time. Every day, we received new decrees that instituted new prohibitions we, as public officers, had to enforce and make people respect. Most of the time, the norms appeared to contradict the ones of the day before. Every day, newspapers and television spoke only of death and contagion. We reach a level of collective delirium. Everyone was looking at everyone else as a possible enemy, a plague carrier. Let alone, what people should have thought seeing us, four idiots running around the neighborhood in multicolored shirts. I can understand why some yelled at us or told us that we were criminals. Try to explain to them that we weren’t hurting anyone. I continued jogging during the lockdown, around my home… but it was quite shitty. It was not real jogging. We were in a cage even if we can technically run. That’s for sure.”

“During the lockdown, I continued to work. […However,] tension and fear were high: a dozen colleagues were affected by the disease or had close relatives affected. […] When I got home, I needed to be distracted; I needed to move [recalls Laura]. As far as I could, I kept jogging [… but] when they put the obligation to run within a few meters from home, I started going around the block. I felt like an idiot, but I continued for a few days. Then the police stopped me. They were about to fine me because I was jogging. We discussed for a good ten minutes before they understood I was just jogging around my block. I read about other joggers being stupidly fined on the internet and I read about people who were starting to run up and down the stairs of their buildings. I live in a ten-story building. I started doing it too: up and down, up, and down. I did not use my shoes because I did not want to bother my neighbors too much. I ran with two pairs of socks to make no noise. There was certainly someone else in the building who ran on the stairs during the night because I could hear the rushing up and down. In the end, I made the stairs go well. In May, the first time I was able to run on the street again without fear of being fined or insulted, I started to cry with happiness.”

“During the lockdown we [Francesco and his wife] worked mostly from home […]. We live outside the city and there are just fields and a few farmhouses around. Thus, we felt we could go jogging without a big fuss. However, in April, we were blocked twice by policemen in civilian dress, and we reckon they were patrolling the area now and then. So, we decided to change time. We started going out in the dark, very early in the morning. We fixed our alarm at 4.30 and we went out. It was crazy, I know…”

3.3. The Experience of the End of the Lockdown

“Well… normally I jog because I feel better… it is for my health… During the lockdown it was different. It was not simple, and I did not feel freedom by jogging during the lockdown. However, it was a way of still feeling in control of my life in a moment of… well… when everything appeared out of control.”

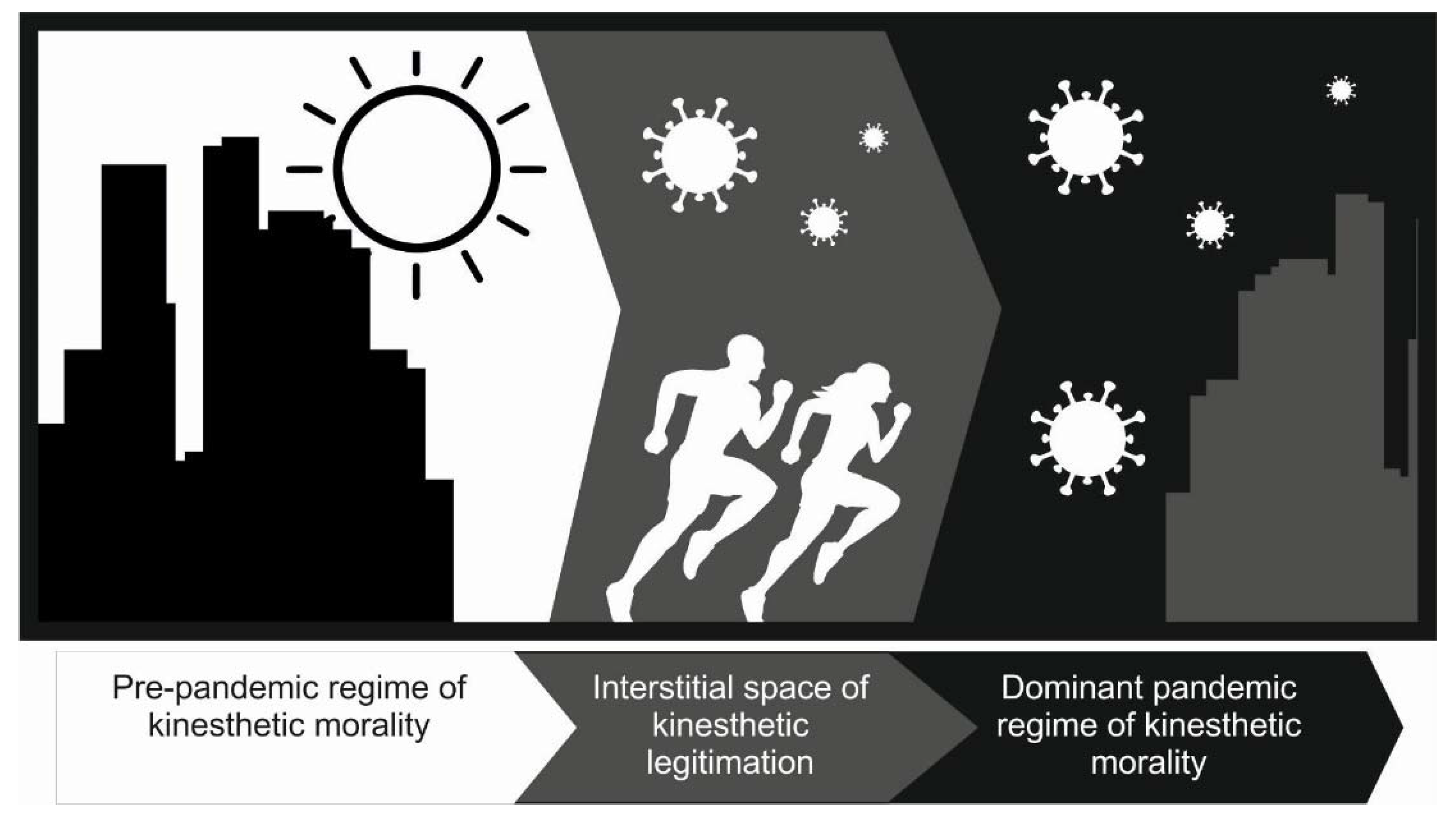

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1. | Overall, the research was conducted from a common perspective to anthropological research in which the researcher is placed within the local reality, being a participant observer of the local context [58]. As pointed out by Bourdieu [59], this perspective is not antithetical to a rigorous social analysis insofar as it is made explicit and the role of the researcher within the research context is objectified. In this sense, my personal experience and involvement with jogging was not a cause of awe or embarrassment, but a factor capable of creating a positive and empathic atmosphere during interviews. |

References

- Rose-Redwood, R.; Kitchin, R.; Apostolopoulou, E.; Rickards, L.; Blackman, T.; Crampton, J.; Rossi, U.; Buckley, M. Geographies of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.; Smart, A. Thoughts about Public Space During Covid-19 Pandemic. City Soc. 2020, 32, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, P. COVID-19 as Atmospheric Dis-ease: Attuning into Ordinary Effects of Collective Quarantine and Isolation. Space Cult. 2020, 23, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.; Lewis, E. Affect and Emotion, Anthropology of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 236–240. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia; Athlone: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, G. Running and Being: The Total Experience; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, A. Pierre Bourdieu and the Sociological Study of Sport: Habitus, Capital and Field. In Sport and Modern Social Theorists; Giulianotti, R., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, A. The history of a habit: Jogging as a palliative to sedentariness in 1960s America. Cult. Geogr. 2015, 22, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillick, M.R. Health Promotion, Jogging, and the Pursuit of the Moral Life. J. Health Politics Policy Law 1984, 9, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Life; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- Camy, J.; Adamkiewics, E.; Chantelat, P. Sporting Uses of the City: Urban Anthropology Applied to the Sports Practices in the Agglomeration of Lyon. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 1993, 28, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, A.; McCormack, D.P. Affective Cities. In Routledge Handbook of Physical Cultural Studies; Silk, M.L., Andrews, D.L., Thorpe, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.; Rose, J.; Standridge, S.H.; Pruitt, C.L. Experiences of urban cycling: Emotional geographies of people and place. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Davidson, J.; Cameron, L.; Bondi, L. Emotion, Place and Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, M. Il Bello Della Bicicletta; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, A.; Szakolczai, A. Walking into the Void: A Historical Sociology and Political Anthropology of Walking; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bodin, M.; Hartig, T. Does the outdoor environment matter for psychological restoration gained through running? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karusisi, N.; Bean, K.; Oppert, J.-M.; Pannier, B.; Chaix, B. Multiple dimensions of residential environments, neighborhood experiences, and jogging behavior in the RECORD Study. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K. Ordinary Affects; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2007; p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Gervasoni, M. Storia D’Italia Degli Anni Ottanta: Quando Eravamo Moderni; Marsilio: Venice, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdea, L.; Michelini, M. L’intensità dell’attività fisica degli occupati. In Proceedings of the AIQUAV 2018. V Convegno Nazionale dell’Associazione Italiana per gli Studi sulla Qualità della Vita, Fiesole (FI), Italy, 13–15 December 2018; Libro dei Contributi Brevi. di Bella, E., Maggino, F., Trapani, M., Eds.; Genoa University Press: Genoa, Italy, 2019; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Patucchi, M. Running “partito di maggioranza”, il 51% degli italiani corre almeno una volta al mese. La Repubblica 2017. Available online: https://www.repubblica.it/sport/running/storie/2017/06/03/news/running_partito_di_maggioranza_il_50_degli_italiani_corre_almeno_una_volta_al_mese-167137753/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Marathonworld. Numeri e curiosità. Marathonworld 2015. Available online: https://www.marathonworld.it/praticanti-running-corsa-maratona-italia-2015.html (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cassa di Risparmio di Alessandria. L’economia Alessandrina Dal Secondo Dopoguerra a Ogg; Cassa di Risparmio di Alessandria SPA: Alessandria, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Caramellino, A. L’archiettura rurale alessandrina. In L’architettura Ruale in Provincia di Alessandria; Caramellino, A., Ed.; Provincia di Alessandria: Alessandria, Italy, 1999; pp. 64–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquariello, M.; Chiesi, G. L’analisi dei determinanti di un’area territoriale. Studio preliminare in preparazione del Piano strategico per il comune di Alessandria. POLIS Work. Pap. 2009, 152, 1–121. [Google Scholar]

- Comune di Alessandria. Convegno Turismo Tempo Libero Sport: Alessandria, 29–30 November 1975; Comune di Alessandria: Alessandria, Italy, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Volpato, G.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Gruppuso, P.; Zocchi, D.M.; Pieroni, A. Baby pangolins on my plate: Possible lessons to learn from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fontefrancesco, M.F. Effetto Lockdown: Come Sono Cambiate le Abitudini Alimentari Degli Italiani Durante L’emergenza COVID-19; Università degli Studi di Scienze Gastronomiche: Bra, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fontefrancesco, M.F. The Urban Disease Revealed In Italy. Anthropol. News 2020. Available online: https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/the-urban-disease-revealed-in-italy/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Guigoni, A.; Ferrari, R. Pandemia 2020. La Vita Quaotidiana in Italia Con il Covid-19; M&J Publishing House: Danyang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Candea, M. Arbitrary locations: In defence of the bounded field-site. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2007, 13, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, C.J. Toward a Variable Conceptualization for Comparative Research. Soc. Hist. 1980, 5, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliara, F.; Gigliuto, L. Di Corsa of Course; Malcor D’: Catania, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball Sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R. The life story interview. In Handbook of Interview Research; Gubrium, J.F., Holstein, J.A., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 2158244014522633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maanen, J. Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, D. Ethnography. In The SAGE Dictionary of Social Research Methods; Jupp, V., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C.; Adams, T.E.; Bochner, A.P. Autoethnography: An Overview. Hist. Soc. Res. Hist. Soz. 2011, 36, 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Weight of the World; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, R.; Martin, E.; Vesperi, M.D. An Anthropology of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anthropol. Now 2020, 12, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decorato, F. AL Il Nemico Invisibile. 2020. Available online: https://radiogold.it/cronaca/251329-libro-fotografie-alessandria-covid-lockdown-nemico-invisibile-fabio-decorato-csva/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Deleuze, G. What is a dispositif? In Michel Foucault, Philosopher: Essays Translated from the French and German; Armstrong, T.J., Ed.; Harvester Wheatsheaf: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, N. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affects; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Logic of Practice; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Westheimer, J.; Kahne, J. What Kind of Citizen? The Politics of Educating for Democracy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2004, 41, 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- di Nardo, F.; Williams, G.; Patterson, L.; Harrison, A.; Verma, A. Current Challenges for Urban Health. Health Policy Non-Commun. Desease Diabetes 2017, 4, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant, L. Body and Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer; Reaktion: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values; Prentice-Hall: Engelwood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Gruppuso, P.; Whitehouse, A. Exploring taskscapes: An introduction. Soc. Anthropol. 2020, 28, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. Affective Economies. Soc. Text 2004, 22, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strenght of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walby, S. Crisis; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley, J.P. Participan Observation; Waveland Press, Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Participant Objectivation. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2003, 9, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Id. | Age Group | Change | Incidents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1M | 30/40 | Interruption | None |

| 2M | 30/40 | Location, Range | Insults |

| 3M | 30/40 | Range, Duration | Police |

| 4M | 30/40 | Interruption | None |

| 5M | 30/40 | Range, Duration | None |

| 6M | 30/40 | Location, Period | Insults |

| 7M | 30/40 | Interruption | Insults |

| 8M Luca | 41/63 | Interruption | Insults |

| 9M Francesco | 41/63 | Period | Police |

| 10M Simone | 41/63 | Range | Insults |

| 11M | 41/63 | Interruption | None |

| 12M | 41/63 | Interruption | None |

| 13M | 41/63 | Range, Duration | Insults |

| 14M | 41/63 | Location | Insults, Attack |

| 15M | 41/63 | Interruption | Insults, Police |

| 16F Laura | 30/40 | Range, Location, Period | Police |

| 17F | 30/40 | Interruption | None |

| 18F | 30/40 | Location, Period | Attack |

| 19F | 30/40 | Range, Duration | None |

| 20F | 30/40 | Interruption | None |

| 21F | 30/40 | Interruption | Police |

| 22F | 30/40 | Range, Period | Police |

| 23F Maria | 41/63 | Interruption | Insults, Attack |

| 24F | 41/63 | Range, Duration | Insults |

| 25F | 41/63 | Interruption | None |

| 26F | 41/63 | Range, Duration | None |

| 27F | 41/63 | Range, Duration | Insults |

| 28F | 41/63 | Interruption | None |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fontefrancesco, M.F. Jogging during the Lockdown: Changes in the Regimes of Kinesthetic Morality and Urban Emotional Geography in NW Italy. Societies 2021, 11, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040124

Fontefrancesco MF. Jogging during the Lockdown: Changes in the Regimes of Kinesthetic Morality and Urban Emotional Geography in NW Italy. Societies. 2021; 11(4):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040124

Chicago/Turabian StyleFontefrancesco, Michele Filippo. 2021. "Jogging during the Lockdown: Changes in the Regimes of Kinesthetic Morality and Urban Emotional Geography in NW Italy" Societies 11, no. 4: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040124

APA StyleFontefrancesco, M. F. (2021). Jogging during the Lockdown: Changes in the Regimes of Kinesthetic Morality and Urban Emotional Geography in NW Italy. Societies, 11(4), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040124