1. Introduction

What are the commercial limits to social identity? Making the assumption that the activities you engage in and objects that you acquire have entertainment and informational value to others, at what point does your presentation of self become a potentially commercialized object? When that presentation of self is displayed on stage, at what point does the audience stop relating to you as the person, versus you as the presentation? In this work, we explore the world of the social media influencer, an individual whose digital presence commands an audience that is receptive to a number of lifestyle and commercial suggestions. This receptivity is achieved through digital communication in online social networks. These influencers, via either their own commercial ventures or via third-party contractual arrangements, advertise and endorse products and services through online communication messaging.

Inter-meshing their own identities and relationships with commercial entanglements, online influencers extend relationship marketing to the digital age. In doing so, they leverage social relationships beyond their immediate social nexus and scale up their reach through digital network technologies. Examining the quantitative dimensions of the communication channels, findings demonstrate that the network morphologies through which individuals are able to sustain an engaged audience are minimally effected by the introduction of commercialism into social relationships. The analysis explores how audience receptivity to commercial content has much less to do with the nature of the content as “advertisement”, and much more to do with the network morphologies that underly that commercial message. Accordingly, we present the hypotheses that (H1) a content message’s status as advertisement, when made explicit, has a statistically significant positive effect on an audience networks’ level of engagement with the message content when viewed on the aggregate; and (H2) an individual’s network size has a significant effect on the audience’s level of engagement with the message content. Both hypotheses are based on presumptions that online social networks’ commercial undertones as an advertising-driven platform have spillover effects into the content generated by its users.

As of 2020, “Instagram”, a product offering of Facebook, Inc., passed over 1 billion registered users in the previous year and has become the predominant channel for influencer marketing. That volume of users combined with the high number of influencers makes Instagram an important platform for research. Similarly, according to a recent survey, nearly 34% of US consumers have make a purchase on the recommendation of an influencer [

1]. Instagram was ranked the most important influencer marketing platform by over 89% of respondents in the survey. Given the extent and magnitude of such commercialization of identities online, not only does the platform offer considerable research opportunities, but also demonstrates the pervasiveness of relationship marketing on a massive scale.

To understand why such a phenomenon of ‘influencing’ is different than social capital acquisition or commercial advertising, we must root the phenomenon in sociological terms. To ‘influence’ is an act of performance. It is an act of commercial intimacy through the use of a micro-celebrity. It is commercial in the sense of involving an economic transaction, yet intimate in the sense of utilizing a window into a semi-private life through the lens of an individual personal mobile device. The micro-celebrity factor is a vehicle of notoriety constructed through digital niche networks on social media. These terms help understand why such behavior is salient on social networking platforms, and why such behavior has the potential to shape cultural outcomes.

2. Background

Ever since E. Goffman’s [

2,

3] early 20th-century theories on social performance, scholars have utilized the stage metaphor in description of individual and group social action. It captures the psychological act of public and private space building and the difference between social orientation of actors within those spaces. The translation of such front-of-stage and back-stage categories to online social media was bound to happen in due course [

4]. Whether that medium be the manifestation of status through competition, or the posing of a photo for internet distribution, the mechanisms of performativity and the analogs to the social act remain the same.

The unique relationship of content production on social media is a dynamic relationship of peer-to-peer consumption through production, or produsage. This modality of interacting with online platforms developed from the prosumption paradigm [

5] in which consumers performed a greater amount of labor in order to consume products and services. In the web 2.0 conceptualization of online behavior, users of online technologies are both involved in the production and consumption of content online simultaneously. In effect, they become both a producer and a consumer of goods and services by engaging in social platform discourse and content generation [

6]. Such content production and consumption has an effect of flattening information hierarchies, but also has the potential to exploit users as a form of free labor [

7]. By interacting with other members online, users engage in a form of sociality that develops from an act of writing or content production that is both aimed at and shaped by the potential reception of such content by other users. Connections between other users, or ‘friendships’ are a form of social boundary making, which presupposes in-group and out-group characterizations. Some individual users are perceived as ‘closer’ and others as more distant from both qualitative and quantitative dimensions.

Instagram is a platform that ‘presupposes a networked intimacy in its adoption of the term “friends” to refer to one’s followers and following’ [

8]. That presupposed networked intimacy by default is not intended to be of a commercial nature. The relationship between a friend and another friend on the platform while existing on a commercial platform is presupposed to be of an organically social nature. That presupposition is one of the factors that make a product or service recommendation more powerful than those seen on other mass-communication platforms. That presupposed intimacy is derived from a sense of ‘context collapse’ [

9]. While there are many different contexts for individuals’ sharing and social circles on social media, the main lining of a single channel to a large number of out-degree relationships effectively pushes context to the lowest common denominator in terms of audience. An individual may feel that while they have a number of social relationships on the platform, some intimate, others distant, the content that is delivered throughout the platform has a presupposition to be suitable for everyone, but designed to be of a more intimate nature than not.

2.1. Commercial Intimacy

Like many other social media platforms, Instagram relies heavily on the production of content that is delivered through socially-mediated relationships. In effect, platform revenue streams rely on individual contributors to produce enough content to outsize the number of advertisement placements. The platform is interested in generating enough non-commercial content that is socially relevant to allow the insertion of commercial advertisement by the platform into the newsfeeds of its users. The mechanisms are similar to a television channel building enough informative and entertaining content to maximize the placements of advertisements and commercial messaging. Expanding the reach of the network through out-degree followers is an effective way for the platform to maximize the delivery of content to individual consumers, yet the creation of those networks involves a give and take between personal and impersonal connection on behalf of users.

Platforms and users tap into what Papacharissi has documented as a grounding of expression and connection in affect [

10]. As social media tap into feelings of engagement that are affordances of the digital technologies themselves, they enable emotional and affective ties through digital traces. Those affective ties can be generated from a wide variety of domains, for example Cervi has shown how social media users derive emotional benefit from the produsage of travel content, which can, in turn, affect future purchasing decisions [

11]. Such affective ties carry over into the realm of advertisement, as much of the tactics in that domain are driven by affective strategies to tie emotional states to a given product or service.

Individuals can increase the size of their out-degree networks by providing useful, entertaining or unique content that offers glimpses into a person’s lived experience. Such content utilizes affective ties to bridge connections in ways that would be difficult through non-digital modalities. For example, Marwick et al. show how celebrities divulge personal information as a way to build intimacy with their out-degree network [

12]. Similarly, Baym documents how individual musicians see their social media audiences as ‘equals’ and reciprocate the uni-directional relationship between artist and consumer [

13]. The connections that are formed via social media networks, while impersonal in their lack of physical connection or direct user-to-user messaging, entail an invitation to semi-private spaces. The ‘informational and entertainment value’ of the social media content lies in the crossing of barriers between public and private spaces, particularly on Instagram. The public space, allowing for commercialism in the public imaginary runs in contradistinction to the private space supposedly shying away from such commercialism. That network relationship, however, is often formed from a commercial nature in the quasi-private realm.

2.2. Instagram

As a mobile device application, Instagram enables users to capture images and videos on their devices and deliver that media to a network of out-degree relationships. Out-degree followers make an implicit assumption that the content is generated from the individual’s personal device. While this is not always the case, as many individuals utilize other higher-end cameras and videos to generate their content, this implicit assumption is built into the platform and provides a sense of intimacy, as their individual is connecting to other individuals from one mobile device to another.

Alhabash et al. document how Instagram is one of the higher use-intensive platforms amongst other popular social networks [

14]. It stands out for its convenience and entertainment values when viewed in comparison to use patterns on other social media networks. That usage, and the fact that content is supposedly derived from the privacy of one’s personal mobile device, invites a large volume of human subjects in the network content. Such content can be photos of other individuals or photos or videos that the individual has taken of themselves (selfies). Bakhshi et al. point to the differentials between photos of faces and all other content on Instagram to highlight how photos of faces drive engagement (likes and comments) much higher than other types of content [

15]. They discover that this effect is consistent across all ages of platform users. Lee et al. also show that motivations for Instagram users are derived predominantly from ‘social interaction, archiving, self-expression, escapism, and peeking’ [

16]. Such motivations, especially the latter, back up the context collapse described by Abidin [

17], and highlight how the personal-ness of the social media network Instagram invites a unique form of receptivity in out-degree networks. In combination with the motivations of users on the network, the content that is generated reflects those incentives and outcomes. Hu et al. provide an analysis of the various categories, bucketing content into 8 categories. In their work, they discover a predominance of photos of friends and selfies as opposed to the rest of the classifications [

18].

2.3. Micro-Celebrity

The concept of micro-celebrity hinges on the functionality in social media to create mini-networks in which broadcast modalities of content distribution are prevalent and betweenness centrality and cliques form on a smaller scale. While notable individuals with a high out-degree count can certainly be found on Instagram, a large number of individuals with a relatively significant number of out-degree relationships (1000–50,000) exist on the platform [

19]. Such individuals are often labeled as ‘micro-influencers’ by marketers and advertising professionals. Their existence in large numbers expands commercial possibilities through the use of paid promotions. When solicited in bulk, micro-influencers can often command similar advertising outcomes as mass media channels. Conceptually, micro-celebrity can be thought of as ‘the commitment to deploying and maintaining one’s online identity as if it were a branded good’ [

20] (p. 346). Utilizing similar methods and strategies to commercial marketing, such identity maintenance crafts and curates an image with reference to its prospective audience as customers, rather than social actors. The act of such maintenance, utilizing Goffman’s [

2,

3] stage terminology, highlights an extensive back-stage rehearsal of a front-of-stage performance. That performance is a form of commercial identity making, which attempts to persuade the audience that there is no front-of-stage/back-stage distinction. It raises the question as to the extent of such preparations and whether such preparations, when commercially motivated, can still maintain their ‘aura’ of individual-ness.

There are distinct consequences to such boundary transgression. For instance, micro-celebrity brings issues to the forefront of the negative effects of curative practices. Brown et al. discuss the effects of such curation on body image, highlighting that the over exposure of curated images has a negative effect on mood and self-perception of one’s own body [

21]. Pittmann also demonstrates that while there are negative effects to such image-based social networks like Instagram, they can have a positive effect on certain emotional states such as loneliness [

22]. Laden within the concept of micro-celebrity is the network power that such individuals command through the social media networks. That network power leads to a unique ability influence others when combined with commercial intimacy.

2.4. Influencers

While the terms micro-celebrity and influencer are not-mutually exclusive, the emphasis on the latter suggests that the individuals in question are actively employing that network power to achieve certain ends. Those ends may be of suggestion for either social or commercial ends. Ends-driven social media behavior, when directed towards a commercial outcome, are powerful tools. A number of studies have examined the power of such individuals in shaping consumer behavior, changing public opinion and motivating collective action. Lim et al. show the impact of such influencer behavior on purchase intention [

23]. Khamis et al. go even further to suggest that influencer culture is an extension of neo-liberal individualism in the digital age [

24]. Despite the network power of influencers, Zhang et al. demonstrate that messages from individual influencers are tied to the user-content fit [

25]. So, in order for users to maintain their network power, there must be an alignment between the identity of the influencer as constructed through their content messages and their audience. This finding is important as it underpins our analysis that out-degree networks that have grown over time are based on the effective harmony between user–message fit. This harmony should manifest itself as individuals consume both non-sponsored and sponsored content on their social media network feeds.

3. Methods

To explore this difference in network power, and the levels of engagement of users with various forms of messages, this study was interested in exploring two distinct ideas. Firstly, we wished to examine how the content of a given message, namely the status of the message as commercial or non-commercial, would effect engagement levels on the post. Broadly, we wished to discover how the receptivity of a message, when viewed in the aggregate, was affected by the commercial underpinning of the message. In those messages that had a commercial underpinning, users were made explicitly aware that the content of the post was an advertisement or ‘sponsored’ by the use user of a hashtag. That convention, which was established as a platform rule, enabled users to detect commercial messages, in the same place as they would be likely to ‘engage’ with the message: near the comment and like buttons. Accordingly, we were interested in the effect of such ‘sponsored’ tagging on the volume of ‘like’ and ‘comment’ actions by others on the social media post. As a way to formalize that engagement, we defined engagement levels for an individual content message (

) as the sum of likes (

l) and comments (

c) divisible by the size of the user’s network followers (

f).

As individual network sizes vary across the sample population, we normalized engagement levels based on out-degree network size. We were also interested in exploring the relationship between the individual’s network power as denoted by follower size (f) and engagement levels of commercial and non-commercial posts. One effect of this form of normalization was to compare engagement levels for users that have various sizes of networks in terms of follower counts. Hence, engagement level is proportional to network reach, not a global rate of ordinal actions. There are some limitations to this approach as highlighted in the discussion section of this work; however, this approach enables us to cross-compare engagement levels across various out-degree network sizes in a way that allows for examination across a wide range of social media follower ranges.

Data Collection

Our data collection process proceeded in two phases: (1) collection of sponsored posts for a 1 month time window and (2) collection of non-sponsored posts for the time window based on the topics found in the sponsored posts. To obtain the required information, a software application was constructed to request live information about Instagram content from the company’s web platform. Making recurring requests for the content over a period of 1 month, data was collected on social media posts. Such data included the body of the content, the number of likes and the number of comments, the poster (user) information regarding their in-degree and out-degree counts, and their profile descriptions. Specifically, on Instagram’s website, we requested the tag page for the #sponsored hashtag and gathered the content from the current time to a month in the past. For phase 1, this process collected content for a one month window from 15 April 2020 to 15 May 2020 to collect all the sponsored posts for that time period as a snapshot of the total population of sponsored posts.

For phase 2, in order to include a control sample to compare engagement levels, we utilized a snowball sample from the sponsored posts themselves (n = 29,273). For example, in a post that had the text, ‘#sponsored. I know you. #summerdrinks #summerdrink #drinkrecipes’, we collected all the hashtags that were not ‘#sponsored‘ from our population of sponsored posts (#summerdrinks #summerdrink #drinkrecipes). We then pulled 29,273 posts from an equal number of non-sponsored hashtags. In sum, we collected 58,547 posts for a four-week period that included an equal number of commercial and non-commercial tagged messages. The collected data included the entire population of sponsored content for the time period, and a sample population of non-sponsored content. As the non-sponsored content population vastly exceeded the number of sponsored content, as well as computational power available, we selected a snowball sample of the snapshot population derived from the sponsored content’s hashtags. Once we obtained a similar size of non-sponsored content, the research moved to the analysis phase. We then tabulated the engagement level for each of those posts.

4. Findings

The results of the analysis showed a heavily skewed level of engagement for the vast number of users. Not only did the majority of users have a follower size (out-degree) of less than 5000, but they also had the highest levels of engagement relative to their total out-degree. There is a significant effect of a post’s classification as ‘sponsored’ on engagement level as demonstrated in

Table 1. The effect is also greater when combined with the out-degree edge counts of the post’s user node.

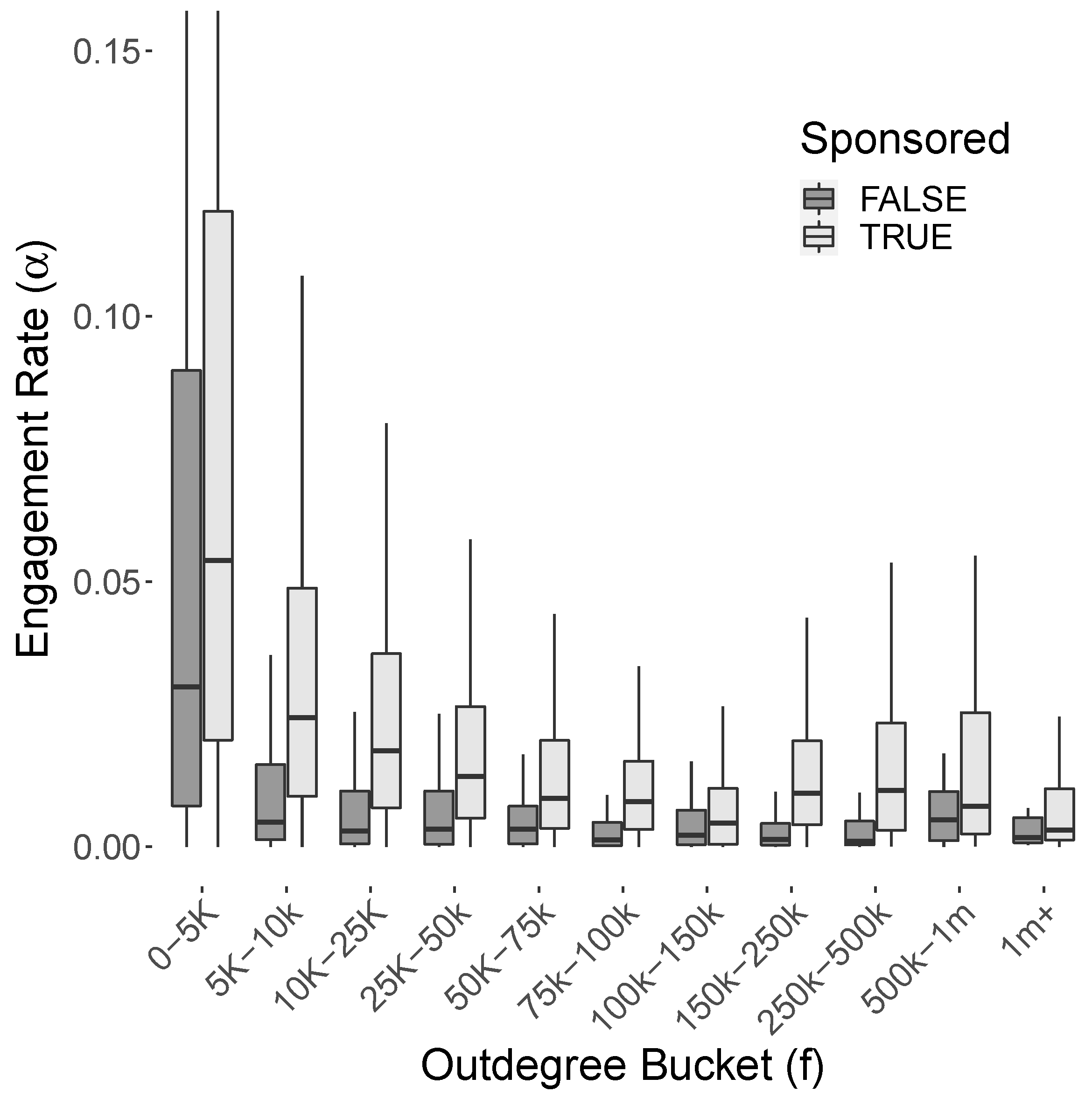

Diving into the summary descriptive statistics of the analysis, we see that the variation between means amongst engagement buckets indicates evidence that supports our initial hypothesis. Firstly, we see that the majority of users fell into the 0–5 K level of out-degree edges, which is common for most social networks. As shown in

Figure 1, we see that the median engagement level is different for sponsored and non-sponsored posts across all out-degree buckets, with the largest difference occurring at the lower end of the spectrum. With regards to our first hypothesis (

H1), we do find that there is a statistically significant difference between messages that are sponsored and non-sponsored. We find that sponsored posts have a higher engagement level across the board for user follower networks of all sizes. This may be due to the amount of effort being put into the construction of a sponsored message being greater than an non-sponsored message, or it may be due to the level of interest in the associated sponsored hashtags having wider reach than other tags that the user may use on non-sponsored content. Additionally, we find evidence to support the second hypothesis (

H2) that engagement levels differ across network size for both sponsored and non-sponsored content.

Looking first at the difference between sponsored and non-sponsored content in

Table 2, it is clear that the effect is approximately similar across all engagement levels (0.1, ±0.05). While engagement levels are higher for smaller networks, the difference between sponsored and non-sponsored content remains relatively consistent across all buckets, with sponsored content having a lead over non-sponsored content.

We see that both hypotheses, (H1) that a message’s status as advertisement has a significant effect on engagement level with the content, and (H2) that the network size has a significant effect on engagement level, are supported by our findings. While it would appear that as an individual’s audience size grows, the engagement level of that audience decreases as a percentage of their total out-degree. Such a finding is consistent with the transition from an individual’s network from organically social and interactive to more broadcast modalities. We can infer that the relationship to an individual changes as an individual out-degree network grows beyond 5K followers. The individual may be producing content that is less tailored to a specific audience, and more standardized towards a general audience.

We also see that in terms of monetization of content on Instagram, a message’s status as ‘sponsored’ does not have a negative effect on engagement levels. In fact, the opposite is true, regardless of the out-degree bucket size. The positive effect is relatively consistent across the spectrum of network sizes. This is likely due to the amount of effort that is placed in sponsored content. Since the individual is provided remuneration for the message, the push towards higher quality is significantly greater than a self-motivated message without commercial undertones.

Micro-celebrity effectively acts as a means for sponsors of social media content to garner a higher engagement level of their sponsored content, despite having a lower reach than individuals who command higher out-degree networks in the millions. What is unique about engagement on Instagram is that the commerciality of the message is intertwined with the nature of the platform to the extent that content ‘quality’ rather than content ‘personality’ has a greater effect on engagement level. By this, it is suggested that the connection to the individual as a non-commercial back-of-stage actor is less important than the quality of the presentation of the individual. If the content of the post, and its status as ‘advertisement’ or ‘sponsored’ had such an effect, we would have seen either an overall decrease in engagement, or a decrease in engagement relative to out-degree network size.

Limitations

The data sample of this study is a snapshot of the content in Instagram across a small window of 1 month. Future longitudinal research should investigate the change in engagement levels across buckets over time. For instance, there may be variation around engagement levels depending on the time of year or the total network size of the platform as it grows and shrinks. This research was limited by platform API access, but could be expanded to collect data synchronously over the course of a longer window.

Additionally, regarding engagement levels, we tabulated the engagement level as a ratio of likes and comments to their out-degree network size. While this helps standardize engagement levels across many different bucket sizes, it ignores the likes and comments derived from individuals who follow hashtags in addition to individuals. Users may be interested in specific topics and not necessarily follow the individual. Further research could incorporate the followers of specific hashtags in addition to followers of individuals.

5. Discussion

The affordances of

produsage on social media provide individuals with an opportunity to shape conversations with other individuals outside of broadcast modalities. By generating content and engaging in communicative practices with other individuals on a peer-to-peer level, they shape conversations in ways that traditional media cannot entertain [

6]. While this interactivity has the potential to flatten hierarchies [

7], it does involve a form of labor that allows other parties to benefit. When individuals attempt to capture some of the economic value that such behavior can produce, this research demonstrates that individuals can succeed in such endeavors. Even when conventions such as labelling content ‘advertising’ are employed which overly dramatize that individuals are commodifying their content, their strategies of performativity are largely successful.

Such performances back up what Papacharissi has proposed–that social media ground expression in affect [

10]. The feelings of engagement and connection build affective ties that transcend beyond overt ‘commerciality’. Even in circumstances where the network morphology between social media users constitutes an imbalance of network power, (e.g., one node with a high out degree, another with a low out degree), we see affective ties strong enough to withstand commerciality in the relationship. We also find support for Pittmann’s findings of image-based social networks’ positive effect on loneliness [

22], and the work of Zhang et al. that influencing behavior is dependent on user content fit [

25].

6. Conclusions

Social media identity, as both a theoretical concept and performed actualization, is undoubtedly intertwined with the platform in which it operates. The commercial undertones that guide conversation channel behavior in ways that often benefit the platform owners at the expense of the individual users. As more and more individuals push the boundaries of their identity to commercialize the acquired relationships on the platform, the ‘performance’ becomes the reality. Commercialism in content, whether understood as part of the medium or as a necessary component to mediating human behavior online, does not curtail the monetization of identity in social media. In some circumstances, said commercialism can even enhance an individual’s network power and engagement with their online community.

The network power and the affective ties of social media influencers push the boundaries of identity in ways in which public figures have long been able to transcend. By either capitalizing on the public’s interest in the back-stage private life of a highly public life, or through inviting emotional ties that would be impossible in other mediums, highly public individuals have always had the power to capitalize on their notoriety. With the rise of micro celebrities, we see a democratization of commerciality of publicity that, as this research demonstrates, is largely unburdened by the limitations of non-commercialized affective ties.