Tourism Dependency and Perceived Local Tourism Governance: Perspective of Residents of Highly-Visited and Less-Visited Tourist Destinations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Do residents who are more economically dependent on tourism perceive local tourism governance differently than those whose incomes do not directly depend on tourism development?

- Do residents of highly-visited (mature) tourist destinations perceive the quality of local tourism governance and the level of involvement of residents in decision making differently than the residents of less-visited destinations?

2. Materials and Methods

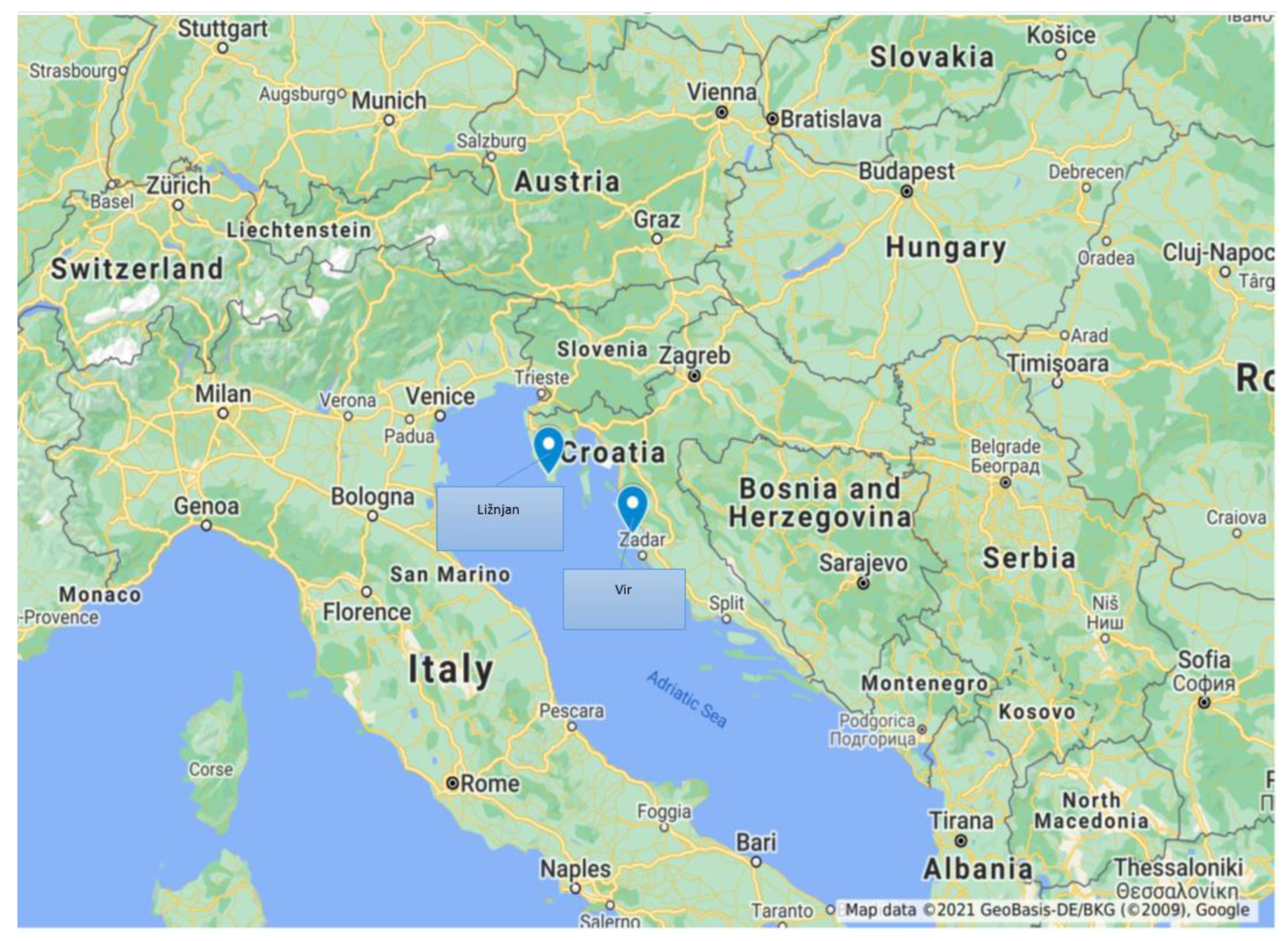

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Methods

- “I am satisfied with the quality of the local private-sector stakeholders’ organization” (variable: private sector organization);

- “I am satisfied with the quality of local public-sector stakeholders’ organization” (variable: public sector organization);

- “I am satisfied with the level of involvement of local residents in tourism-related planning and decision making” (variable: involvement of residents).

2.3. Sample

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gossling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J.; Novelli, M. Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel & Tourism; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Villace-Molinero, T.; Fernandez-Munoz, J.J.; Orea-Giner, A. Understanding the new post-COVID-19 risk scenario: Outlooks and challenges for a new era of tourism. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Song, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F. Designing tourism governance: The role of local residents. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadinejad, A.; Moyle, B.D.; Scott, N.; Kralj, A.; Nunkoo, R. Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A review. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Vogt, C.A. The Relationship between Residents’ Attitudes toward Tourism and Tourism Development Options. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G.; Konovalov, E.; Murphy, L.; McGehee, N. Mobilities, community well-being and sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 532–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Tourism development and sustainable well-being: A Beyond GDP perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldić Frleta, D.; Đurkin Badurina, J. Well-Being and Residents’ Tourism Support—Mature Island Destination Perspective. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2020, 23, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Berno, T. Beyond Social Exchange Theory Attitudes Toward Tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1556–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K.; Johnson, R. Modelling resident attitudes towards tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.; Rodrigues, A.; Fernandes, D.; Pires, C. The role of local government management of tourism in fostering residents support to sustainable tourism development: Evidence from a Portuguese historic town. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2016, 6, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, P.C. Resident attitudes toward heritage tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Porras-Bueno, N.; de los Ángeles Plaza-Mejía, M. Explaining residents’ attitudes to tourism. Is a universal model possible? Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 460–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida García, F.; Balbuena Vázquez, A.; Cortés Macías, R. Resident’s attitudes towards the impacts of tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-X.; Choong, Y.-O.; Ng, L.-P. Local residents’ support for sport tourism development: The moderating effect of tourism dependency. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 24, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.J.; Zhou, J.Y.; Lu, T.Y.; Kim, T.T. The moderating effects of resident characteristics on perceived gaming impacts and gaming industry support: The Case of Macao. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teye, V.; Sönmez, S.F.; Sirakaya, E. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, N.; Dredge, D. Local tourism governance: A comparison of three network approaches. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presenza, A.; Del Chiappa, G.; Sheehan, L. Residents’ engagement and local tourism governance in maturing beach destinations. Evidence from an Italian case study. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. A typology of governance and its implications for tourism policy analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, A.C.; Nóbrega, W.R. Governance in tourist destinations: Challenges in modern Society. Braz. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R. Governance and sustainable tourism: What is the role of trust, power and social capital? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurkin, J.; Perić, M. Organising for community-based tourism: Comparing attitudes of local residents and local tourism entrepreneurs in Ravna Gora, Croatia. Local Econ. 2017, 32, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldić Frleta, D.; Đurkin Badurina, J. Factors affecting residents’ support for cultural tourism development. In Proceedings of the ToSEE—Tourism in Southern and Eastern Europe Creating Innovative Tourism Experiences: The Way to Extend the Tourist Season, Opatija, Croatia, 16–18 May 2019; pp. 641–653. [Google Scholar]

- Wesley, J.M.; Ainsworth, E.L. Creating Communities of Choice: Stakeholder Participation in Community Planning. Societies 2018, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dangi, T.B.; Petrick, J.F. Augmenting the Role of Tourism Governance in Addressing Destination Justice, Ethics, and Equity for Sustainable Community-Based Tourism. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 2, 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- CBS—Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Tourist Arrivals and Nights in 2019. Available online: http://www.dzs.hr/ (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Vir Tourism. Available online: https://www.virturizam.hr/en/island-vir/2021 (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Troncoso Skidmore, S.; Thompson, B. Bias and precision of some classical ANOVA effect sizes when assumptions are violated. Behav. Res. 2013, 45, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duro, J.A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Turrion-Prats, J.; Fernández-Fernández, M. Covid-19 and tourism vulnerability. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, C.H. Residents’ preferences for involvement in tourism development and influences from individual profiles. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2013, 10, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, G.; Pedrini, G.; Zamparini, L. Assessing perceived job quality among seasonal tourism workers: The case of Rimini, Italy. Tour. Econ. 2020. (online first). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukhu, R.; Singh, S. Perceived Sustainability of Seasonal Employees on Destination and Work—A Study in the Tourism Industry. In Sustainable Human Resource Management; Vanka, S., Rao, M.B., Singh, S., Pulaparthi, M.R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlić, I.; Portolan, A.; Puh, B. (Un)supported current tourism development in UNESCO protected site. The case of Old City of Dubrovnik. Economies 2017, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodwin, H. Overtourism: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment. Available online: https://responsibletourismpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/TWG16-Goodwin.pdf/ (accessed on 27 October 2019).

- Butcher, J. The War on Tourism. Spiked Online 2020. Available online: https://www.spiked-online.com/2020/05/04/the-war-on-tourism (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Pavlinović Mršić, S.; Čale, D. Analysis of the ETIS system of indicators for the assessment and monitoring of tourism sustainability in the city of Split, Croatia. Oeconomica Iadert. 2020, 10, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Inhabitants (According to 2011 Census) | Number of Visitors in 2019 [30] | |

|---|---|---|

| Vir | 3000 | 95,413 |

| Ližnjan | 3965 | 32,611 |

| Vir (n = 265) | Ližnjan (n = 149) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 126 | 51.3 | 61 | 40.9 |

| Female | 128 | 48.3 | 84 | 56.4 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.4 | 4 | 2.7 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–25 | 39 | 14.7 | 3 | 2.0 |

| 26–35 | 70 | 26.4 | 23 | 15.4 |

| 36–45 | 51 | 19.2 | 46 | 30.9 |

| 46–55 | 52 | 19.6 | 39 | 26.2 |

| >56 | 53 | 20.0 | 38 | 25.5 |

| Education | ||||

| Elementary school | 18 | 6.8 | 3 | 2.0 |

| High school | 155 | 58.5 | 55 | 36.9 |

| College | 81 | 30.6 | 69 | 46.3 |

| Master/PhD | 10 | 3.8 | 18 | 12.1 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.4 | 4 | 2.7 |

| Connection to tourism | ||||

| Permanent work in tourism | 61 | 23.0 | 10 | 6.7 |

| Seasonal employment in tourism | 33 | 12.5 | 9 | 6.0 |

| Tourism as additional source of income (private accommodation owners) | 53 | 20.0 | 74 | 49.7 |

| No relation to tourism | 118 | 44.5 | 56 | 37.6 |

| Permanent Work in Tourism | Seasonal Employment in Tourism | Tourism as Additional Source of Income (Private Accommodation Owners) | No Relation to Tourism | F | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | St. Dev. | Mean | St. Dev. | Mean | St. Dev. | Mean | St. Dev. | |||

| Private sector organization | 3.29 | 1.175 | 2.55 | 1.216 | 3.20 | 1.305 | 2.34 | 1.196 | 15,309 | 0.000 |

| Public sector organization | 3.26 | 1.432 | 2.51 | 1.330 | 2.90 | 1.314 | 2.13 | 1.192 | 13,663 | 0.000 |

| Involvement of residents | 2.93 | 1.295 | 2.30 | 1.281 | 2.42 | 1.306 | 1.74 | 1.046 | 15,115 | 0.000 |

| Dependent Variable | (I) | (J) | Mean Difference (I–J) | Std. Error | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private sector organization | Seasonal | Permanent | −0.736 * | 0.240 | 0.012 |

| Additional income | −0.655 * | 0.183 | 0.002 | ||

| No connection | 0.204 | 0.173 | 0.641 | ||

| Permanent | Seasonal | 0.736 * | 0.240 | 0.012 | |

| Additional income | 0.081 | 0.219 | 0.983 | ||

| No connection | 0.941 * | 0.212 | 0.000 | ||

| Additional income | Seasonal | 0.655 * | 0.183 | 0.002 | |

| Permanent | −0.081 | 0.219 | 0.983 | ||

| No connection | 0.860 * | 0.144 | 0.000 | ||

| No connection | Seasonal | −0.204 | 0.173 | 0.641 | |

| Permanent | −0.941 * | 0.212 | 0.000 | ||

| Additional income | −0.860 * | 0.144 | 0.000 | ||

| Public sector organization | Seasonal | Permanent | −0.755 * | 0.249 | 0.014 |

| Additional income | −0.391 | 0.190 | 0.168 | ||

| No connection | 0.375 | 0.180 | 0.161 | ||

| Permanent | Seasonal | 0.755 * | 0.249 | 0.014 | |

| Additional income | 0.364 | 0.228 | 0.380 | ||

| No connection | 1.130 * | 0.220 | 0.000 | ||

| Additional income | Seasonal | 0.391 | 0.190 | 0.168 | |

| Permanent | −0.364 | 0.228 | 0.380 | ||

| No connection | 0.765 * | 0.149 | 0.000 | ||

| No connection | Seasonal | −0.375 | 0.180 | 0.161 | |

| Permanent | −1.130 * | 0.220 | 0.000 | ||

| Additional income | −0.765 * | 0.149 | 0.000 | ||

| Involvement of residents | Seasonal | Permanent | −0.633 | 0.251 | 0.064 |

| Additional income | −0.122 | 0.191 | 0.920 | ||

| No connection | 0.554 * | 0.171 | 0.009 | ||

| Permanent | Seasonal | 0.633 | 0.251 | 0.064 | |

| Additional income | 0.511 | 0.231 | 0.130 | ||

| No connection | 1.187 * | 0.215 | 0.000 | ||

| Additional income | Seasonal | 0.122 | 0.191 | 0.920 | |

| Permanent | −0.511 | 0.231 | 0.130 | ||

| No connection | 0.676 * | 0.140 | 0.000 | ||

| No connection | Seasonal | −0.554 * | 0.171 | 0.009 | |

| Permanent | −1.187 * | 0.215 | 0.000 | ||

| Additional income | −0.676 * | 0.140 | 0.000 |

| Vir | Ližnjan | t Sig. (2-Tailed) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Private sector organization | 2.47 | 1.252 | 3.21 | 1.233 | t = −5.826 p = 0.000 |

| Public sector organization | 2.42 | 1.385 | 2.77 | 1.220 | t = −2.689 p = 0.008 |

| Involvement of residents | 2.10 | 1.280 | 2.28 | 1.213 | t = −1.347 p = 0.179 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Đurkin Badurina, J.; Soldić Frleta, D. Tourism Dependency and Perceived Local Tourism Governance: Perspective of Residents of Highly-Visited and Less-Visited Tourist Destinations. Societies 2021, 11, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030079

Đurkin Badurina J, Soldić Frleta D. Tourism Dependency and Perceived Local Tourism Governance: Perspective of Residents of Highly-Visited and Less-Visited Tourist Destinations. Societies. 2021; 11(3):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030079

Chicago/Turabian StyleĐurkin Badurina, Jelena, and Daniela Soldić Frleta. 2021. "Tourism Dependency and Perceived Local Tourism Governance: Perspective of Residents of Highly-Visited and Less-Visited Tourist Destinations" Societies 11, no. 3: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030079

APA StyleĐurkin Badurina, J., & Soldić Frleta, D. (2021). Tourism Dependency and Perceived Local Tourism Governance: Perspective of Residents of Highly-Visited and Less-Visited Tourist Destinations. Societies, 11(3), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030079