Portrayal of Immigrants in Danish Media—A Qualitative Content Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Perspectives Underpinning the Study

3. Materials and Methods

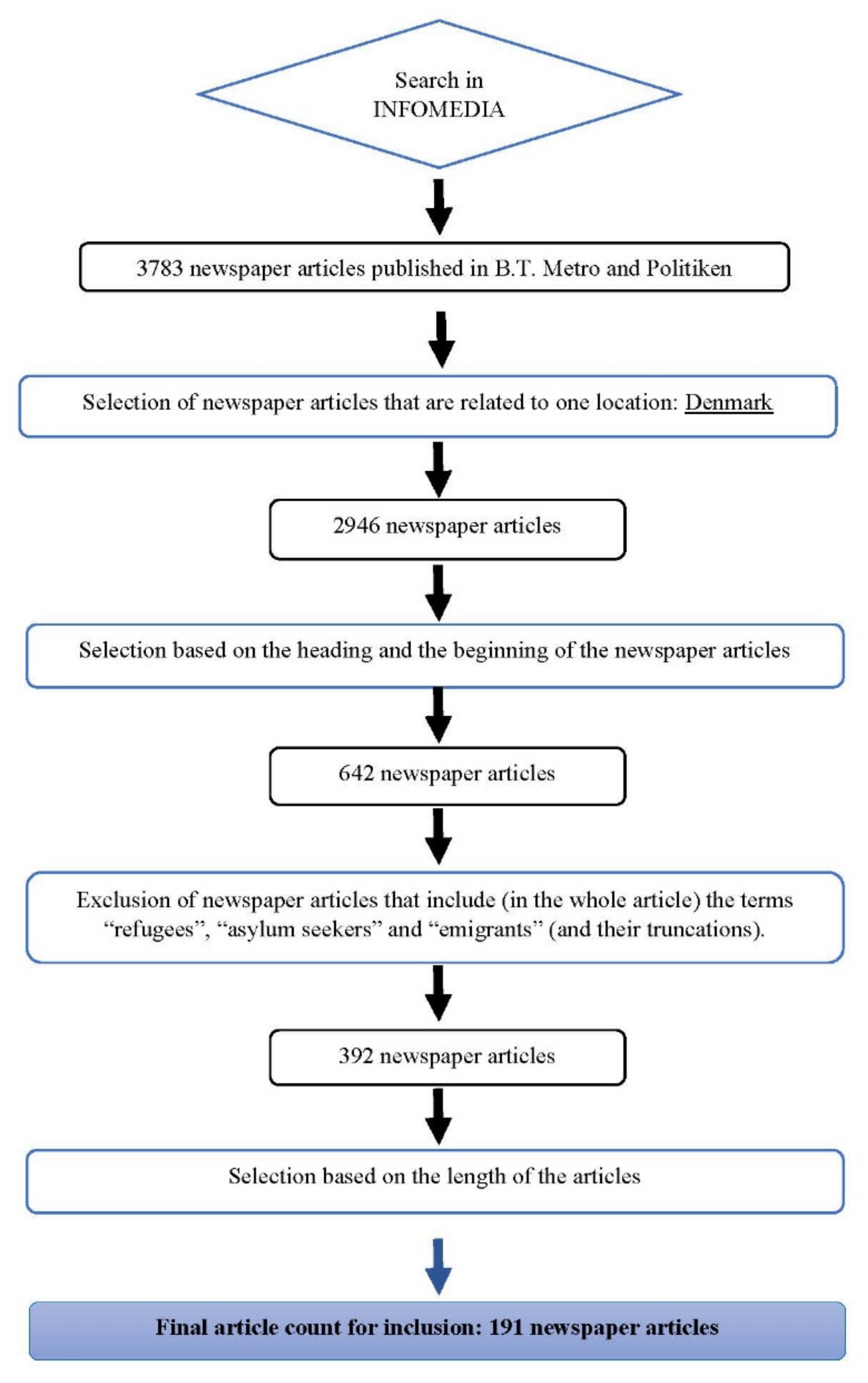

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Qualitative Content Analysis

3.3. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Portrayal of Immigrants

One should not have read much in the Qur’an or followed the news very much without understanding the seriousness and quickly ascertaining the debilitating reality: violence against women, honour killings and serious violations in these Muslim environments.(‘B.T. Metro’, 7 October 2019)

The claim that Muslims give birth to 3-4-5 children is not true.(‘Politiken’, 8 May 2019)

[The woman], who speaks and writes Danish and has learned it in just 11 months (…), has never received social benefits.(‘B.T. Metro’, 31 May 2019)

It has not been easy for Iamae to say goodbye to her friends, family and studies in Brazil—her country, which she loves. But because of Lasse’s illness, she needed to do it, so they could live together.(‘B.T. Metro’, 2 November 2019)

Somalis (…) are the foreign nationality most frequently convicted of pernicious crime, such as murder/attempted murder, violence and robbery.(‘B.T. Metro’, 1 June 2019)

Far too many women with non-Western backgrounds are not in the labour market.(‘B.T. Metro’, 15 June 2019)

In Denmark, it is often talked about that other cultures, other values and backgrounds can be part of the cause of violence and crime.(‘B.T. Metro’, 19 November 2019)

A good place to start is to say thank you to the many citizens of foreign descent who drive our buses, empty our garbage bins, provide care for our elderly and clean our workplaces while others are laying around and sleeping. Thank you for your efforts. Denmark would be a poorer country without you!.(‘Politiken’, 21 May 2019)

He does not buy the story that well over half of women from Arab countries are some poor people who are frozen out of a discriminatory labour market. Tesfaye’s implicit postulate is such that there is work for everyone who wants to work.(‘Politiken’, 27 January 2019)

The most obvious explanation [for their low employment rate] is that their human capital is too weak. They are too poorly educated, their language skills are too weak, they have too little experience with the Danish labour market, which is why their employment-relevant networks many times do not exist at all…when non-Western women are educated, they actually use the education to a great extent to get to work afterwards.(‘Politiken’, 26 September 2019)

I needed to reflect on my Pakistani and Danish roots, and I have learned to set my own boundaries. (…) I need to break some of the patterns that have been created through generations.(‘Politiken’, 10 February 2019)

In a Danish family, she had seen that men could also cook and set the table. And she went home to her own traditional home and demanded that the men do this. (…) Today, (…) [she] is an independent activist, speaker, consultant, moderator.(‘Politiken’, 15 February 2019)

[She] gradually changed her sceptical attitude. Now she advises her friends to send their daughters to school.(‘Politiken’, 10 February 2019)

There are foreigners that we do not want in this country, but which, unfortunately, we also cannot send home right now, because they risk being subject to the death penalty or torture in their home country.(‘Politiken’, 26 September 2019)

4.2. Issues around Immigrants and Immigration

4.2.1. Integration—Success or Failure

Studies show that an increasing number of Muslims want to break the foundations in Denmark and establish Islamic religious law instead of the constitution.(‘B.T. Metro’, 14 May 2019)

Darkened Muslim forces in Denmark play with completely different rules of game than all of us democratic and freedom-loving Danes do.(‘B.T. Metro’, 7 October 2019)

We must be able to speak openly and critically about the role of Islam in Danish society, just as we must maintain that Denmark is based on free Christian values.(‘B.T. Metro’, 30 November 2019)

The state spends 33 billion kroner a year on non-Western immigration. Read again: 33 billion—it’s a kind of (tax) kroner anyway. AN AMOUNT THAT should strictly be zero—or almost zero.(‘B.T. Metro’, 14 May 2019)

Integration must work, not just cost money. (…) [There has been] more than 15 years of the uncontrolled use of public funds for the world’s coloured integration projects.(‘Politiken’, 7 July 2019)

4.2.2. Discourse on Discrimination

If it’s not Ramadan, then it’s our clothing. And if it’s not our clothing, then it’s obviously our names. Everything about immigrants is obviously problematic.(‘B.T. Metro’, 2 February 2019)

Herning Municipality received harsh criticism from the Institute for Human Rights for illegal discrimination on the basis of ethnicity in school relocation.(‘B.T. Metro’, 29 November 2019)

There are examples of discrimination against students with foreign-sounding names like Yousef—not because the teachers are racist but because they are hard pressed. Therefore, they can better accommodate Mathias and his like.(‘Politiken’, 24 March 2019)

Native language teaching in the sense of teaching minority mother tongues has not been considered enriching for the pupils in question in the same way as [teaching] Danish as a native language.(‘Politiken’, 24 March 2019)

For decades, Danish and a narrow form of Danishness have been the norm in the education system, in which bilingualism, teaching minority mother tongues and interculturalism have had difficult circumstances.(‘Politiken’, 24 March 2019)

There is a deep concern that there are some in Denmark who seem to think that people should be expelled solely because of their faith. 28 percent of the surveyed Danes either fully or partially agree that Muslims should be sent out of Denmark.(‘B.T. Metro’, 17 November 2019)

4.3. Discourses Revealing Xenophobia

With 63,537 votes, equivalent to 1.88 percent, Stram Kurs became eligible for party support of more than 2 million kroner a year and is now continuing its anti-Muslim campaign with more resources than they had before the election.(‘Politiken’, 27 October 2019)

Just because a generation decides that now there must be a lot of coloured people, they are not entitled to it. The next generation may not agree that they should grow up in a multicultural society (…). I hope to stop the flow of migrants to Europe. The whole of Europe will be transformed into a shithole because those people cannot contribute or fit culturally with us.(‘Politiken’, 19 May 2019)

25,000 people came on the Syrian wave that should be thrown home. They have no right to be here, and we have nothing to use them for.(‘Politiken’, 19 May 2019)

Denmark is in a desperate situation where the Danes are being exterminated. It’s because of immigration, and it doesn’t matter if it’s from Arab, Asian or Eastern European countries.(‘Politiken’, 19 May 2019)

Discourses around Danish Immigration Policy

The minister will use ‘all the tools we have available’ to reduce the number of people ‘on tolerated stay’. They have long been a rock in the shoes of the minister at all times in the field, and now the stone seems to have become larger.(‘Politiken’, 26 September 2019)

The strategy is to cripple the freedom of movement of the convicts and—despite international conventions—give them such intolerable conditions that they move [out of the country].(‘Politiken’, 3 February 2019)

4.4. Voices Presented and General Tone Used

5. Discussion

5.1. Portrayal of Immigrants

5.2. Issues around Immigrants and Immigration Described by the Media

5.2.1. About Integration

5.2.2. About the Discourse on Racial Discrimination and Xenophobia

5.3. Whose Voices Were Heard?

5.4. Media Discourses’ Potential Effects on Migrants and Immigration

5.5. Limitations

5.6. Strengths and Future Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. B.T. (Berlinske Tidene)

Appendix A.2. Politiken

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. International Migration Report 2017: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/404); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fietkau, S.; Hansen, K.M. How perceptions of immigrants trigger feelings of economic and cultural threats in two welfare states. Eur. Union Politics 2018, 19, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegert, K.; Hovden, J.F. Identity, empathy and argument: Immigrants in culture and entertainment journalism in the scandinavian press. Javn. Public 2019, 26, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, J.M.; Meltzer, C.E.; Heidenreich, T.; Herrero, B.; Theorin, N.; Lind, F.; Berganza, R.; Boomgaarden, H.G.; Schemer, C.; Strömbäck, J. The European media discourse on immigration and its effects: A literature review. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2018, 42, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, C.; Jacobs, L. Television News Content of Minority Groups as an Intergroup Context Indicator of Differences Between Target-Specific Prejudices. Mass Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovden, J.F.; Mjelde, H. Increasingly Controversial, Cultural, and Political: The Immigration Debate in Scandinavian Newspapers 1970–2016. Javn. Public 2019, 26, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enroth, N. EU citizens and undocumented migrants in the news: Quantitative patterns of representation in Swedish news media 2006–2016. Nord. Soc. Work Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.; Garcia-Blanco, I.; Moore, K. Press Coverage of the Refugee and Migrant Crisis in the EU: A Content Analysis of Five European Countries; Project Report; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/56bb369c9.html (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Yilmaz, F. How the Workers Became Muslims: Immigration, Culture, and Hegemonic Transformation in Europe; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbour, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sniderman, P.M.; Hagendoorn, L.; Prior, M. Predisposing factors and situational triggers: Exclusionary reactions to immigrant minorities. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2004, 98, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberger, G. Portrayal of immigrants in news magazines. Migr. Etn. Teme 2004, 20, 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, R.; Scholten, P. Framing the immigration policy agenda: A qualitative comparative analysis of media effects on dutch immigration policies. Int. J. Press/Politics 2017, 22, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauzy, J.P.; Appave, G. Communicating Effectively about Migration. In Reporting at the Southern Borders: Journalism and Public Debates on Immigration in the US and the EU; Dell’Orto, G., Birchfield, V., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Van Klingeren, M.; Boomgaarden, H.G.; Vliegenthart, R.; de Vreese, C.H. Real world is not enough: The media as an additional source of negative attitudes toward immigration, comparing Denmark and the Netherlands. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 31, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomgaarden, H.G.; Vliegenthart, R. How news content influences anti-immigration attitudes: Germany, 1993–2005. Eur. J. Political Res. 2009, 48, 516–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, B.N. Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, K.M.; Jakobsen, V. Køn, Etnicitet og Barrierer for Integration. Fokus på Uddannelse, Arbejde og Foreningsliv [Gender, Ethnicity and Barriers for Integration]. Rep. No. 05(01), 1–114; Socialforskningsinstituttet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ólafs, H.; Zielińska, M. “I Started to Feel Worse When I Understood More”: Polish Immigrants and the Icelandic Media, in Thjóðarspegillinn 2010; Social Science Research Institute, University of Iceland: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Number of Immigrants in Denmark in 2020, by Country of Origin. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/571909/number-of-immigrants-indenmark-by-country-of-origin/ (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Tajfel, H. Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sides, J.; Citrin, J. European Opinion about Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests and Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. The Spectacle of the ‘Other’. In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices; Hall, S., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1997; pp. 225–290. [Google Scholar]

- Pinchevski, A. Alterity. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy; Wiley-Blackwell-ICA International Encyclopedias of Communication Series; Jensen, K.B., Craig, R.T., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2016; pp. 719–729. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behaviour. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.W. Realistic group conflict theory: A review and evaluation of the theoretical and empirical literature. Psychol. Rec. 1993, 43, 395–413. [Google Scholar]

- ILO; IOM; OHCHR. International Migration, Racism, Discrimination and Xenophobia. Geneva: UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online: http://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/international_migration_racism.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Boehnke, K. Cited in Akokpari and Matlosa: International Migration, Xenophobia and Policy Challenges for Regional Integration in Southern Africa, Pretoria, July 2001.

- United Nations, Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner. The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, Article 1. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cerd.aspx (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondracki, N.L.; Wellman, N.S.; Amundson, D.R. Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvale, S. Doing Interviews; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.G.; Weibel, K.; Vitus, K. ‘There is no racism here’: Public discourses on racism, immigrants and integration in Denmark. Patterns Prejud. 2017, 51, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, E.; Foldspang, A. Discrimination, mental problems and social adaptation in young refugees. Eur. J. Public Health 2008, 18, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, H.; McMahon, S.; Jones, K. Victims and Villains: Migrant Voices in the British Media; Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University: Coventry, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, U.M.; Simon, E. Das bild der migranten im WDR fernsehen. Ergebnisse einer empirischen programmanalyse. Media Perspekt. 2005, 3, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Masini, A.; Van Aelst, P.; Zerback, T.; Reinemann, C.; Mancini, P.; Mazzoni, M.; Damiani, M.; Coen, S. Measuring and explaining the diversity of voices and viewpoints in the news. J. Stud. 2018, 19, 2324–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cengiz, P.-M.; Eklund Karlsson, L. Portrayal of Immigrants in Danish Media—A Qualitative Content Analysis. Societies 2021, 11, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020045

Cengiz P-M, Eklund Karlsson L. Portrayal of Immigrants in Danish Media—A Qualitative Content Analysis. Societies. 2021; 11(2):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020045

Chicago/Turabian StyleCengiz, Paula-Manuela, and Leena Eklund Karlsson. 2021. "Portrayal of Immigrants in Danish Media—A Qualitative Content Analysis" Societies 11, no. 2: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020045

APA StyleCengiz, P.-M., & Eklund Karlsson, L. (2021). Portrayal of Immigrants in Danish Media—A Qualitative Content Analysis. Societies, 11(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020045