A Scoping Review of Sport National Concussion Guidelines in Squash

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. What Is Sports Related Concussion (SRC) and Why Is It Important?

1.2. The Amsterdam Statement

1.3. Are Squash Players at Risk of Concussion?

1.4. Who Regulates Squash?

1.5. Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stage 1: Identify the Research Question(s)

- Which national squash governing bodies have published concussion guidelines appropriate for use in squash?

- If a country does not have a squash-specific concussion guideline, does it have a national or grassroots sport concussion guideline that is appropriate for use in squash?

- Do the current guidelines follow the Amsterdam Statement recommendations?

2.2. Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Stage 3: Study Selection

2.4. Stage 4 and 5: Charting the Data and Collating, Summarising, and Reporting Results

3. Results

3.1. Individual Country’s Guidelines

3.2. Recognition

3.3. Rest and Return to Play (RTP)

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

4.2. Individual Country’s Guidelines

4.3. Recognition of Concussion

4.4. Rest and Return to Play

4.5. Implications of Research

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

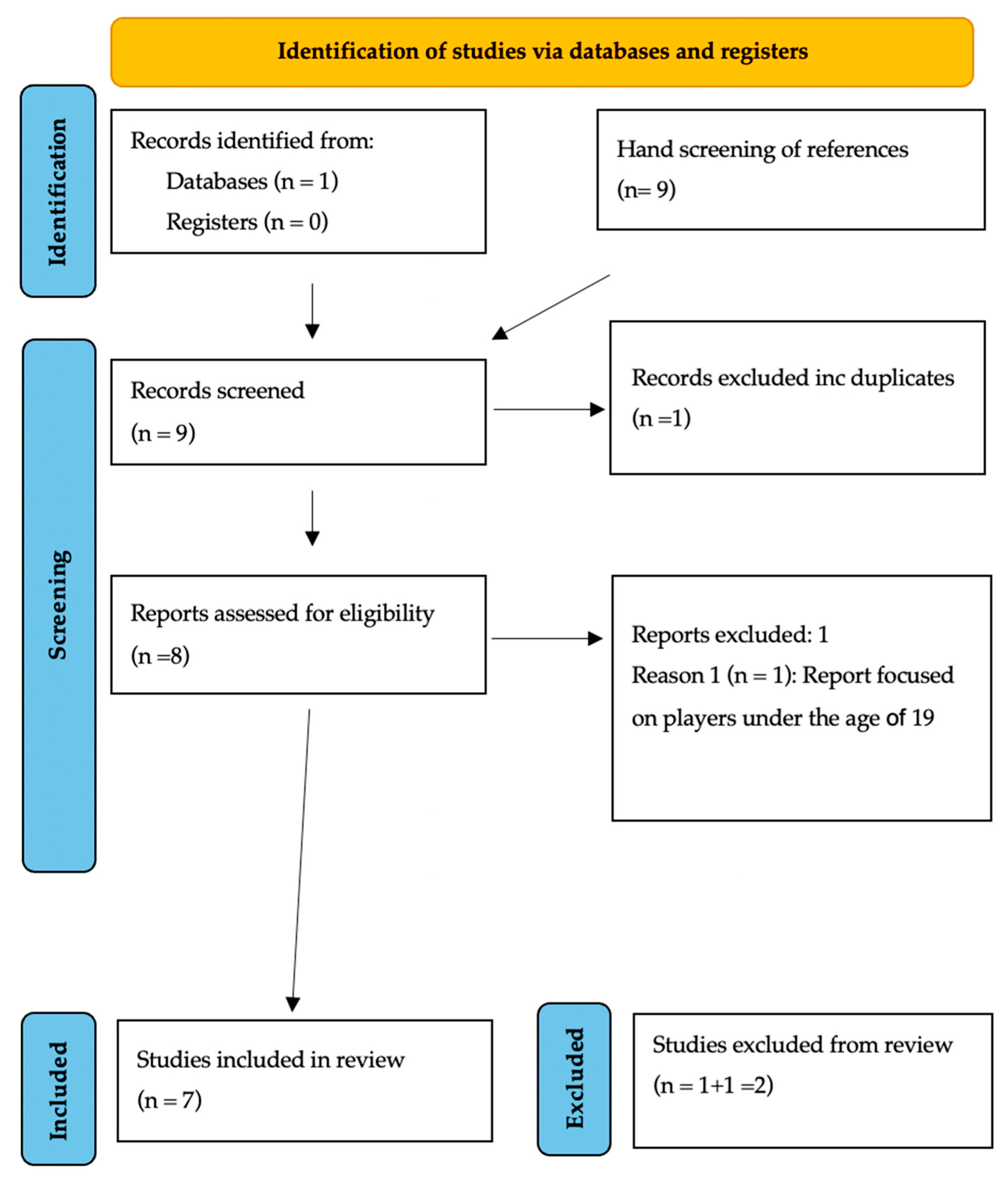

Appendix A. PRISMA Flow Diagram for Scoping Review

References

- McCrory, P.; Feddermann-Demont, N.; Dvořák, J.; Cassidy, J.D.; McIntosh, A.; Vos, P.E.; Echemendia, R.J.; Meeuwisse, W.; Tarnutzer, A.A. What is the definition of sports-related concussion: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS Inform. Concussion. NHS 24:UK. 2025. Available online: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/injuries/head-and-neck-injuries/concussion/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Daly, E.; Pearce, A.J.; Finnegan, E.; Cooney, C.; McDonagh, M.; Scully, G.; McCann, M.; Doherty, R.; White, A.; Phelan, S.; et al. An assessment of current concussion identification and diagnosis methods in sports settings: A systematic review. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tator, C.H. Concussions and their consequences: Current diagnosis, management and prevention. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2013, 185, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, T.; Foris, L.A.; Donnally, C.J., III. Second Impact Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448119/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- McLendon, L.A.; Kralik, S.F.; Grayson, P.A.; Golomb, M.R. The Controversial Second Impact Syndrome: A Review of the Literature. Pediatr. Neurol. 2016, 62, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, G.; Gardner, A.J.; Schneider, K.J.; Guskiewicz, K.M.; Bailes, J.; Cantu, R.C.; Castellani, R.J.; Turner, M.; Jordan, B.D.; Randolph, C.; et al. A systematic review of potential long-term effects of sport-related concussion. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patricios, J.S.; Schneider, K.J.; Dvorak, J.; Ahmed, O.H.; Blauwet, C.; Cantu, R.C.; Davis, G.A.; Echemendia, R.J.; Makdissi, M.; McNamee, M.; et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: The 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport–Amsterdam, October 2022. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrory, P.; Meeuwisse, W.; Dvořák, J.; Aubry, M.; Bailes, J.; Broglio, S.; Cantu, R.C.; Cassidy, D.; Echemendia, R.J.; Castellani, R.J.; et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: The 5th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, M.; Cantu, R.; Dvorak, J.; Graf-Baumann, T.; Johnston, K.; Kelly, J.; Lovell, M.; McCrory, P.; Meeuwisse, W.; Schamasch, P. Summary and agreement statement of the First International Conference on Concussion in Sport, Vienna 2001. Physician Sportsmed. 2002, 30, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrory, P.; Johnston, K.; Meeuwisse, W.; Aubry, M.; Cantu, R.; Dvorak, J.; Graf-Baumann, T.; Kelly, J.; Lovell, M.; Schamasch, P. Summary and agreement statement of the 2nd International Conference on Concussion in Sport, Prague 2004. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrory, P.; Meeuwisse, W.; Johnston, K.; Dvorak, J.; Aubry, M.; Molloy, M.; Cantu, R. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: The 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2008. S. Afr. J. Sports Med. 2009, 21, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, P.; Meeuwisse, W.H.; Aubry, M.; Cantu, B.; Dvořák, J.; Echemendia, R.J.; Engebretsen, L.; Johnston, K.; Kutcher, J.S.; Raftery, M.; et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: The 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Squash Federation. Rules of Singles Squash 2024; World Squash Federation: Hastings, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.worldsquash.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/240102_Rules-of-Singles-Squash-2024-V1.2.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Finch, C.; Eime, R. The epidemiology of squash injury. Int. Sport. J. 2001, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- PSA Squash Tour. Lucas Serme Withdraws US Open Third Round (10 October 2022). Available online: https://www.psasquashtour.com/news/lucas-serme-withdraws-us-open-third-round/ (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- PSA Squash Tour. Cardenas Pulls Out PSA World Championship Third Round (12 May 2025). Available online: https://www.psasquashtour.com/featured-news/cardenas-pulls-out-psa-world-championship-third-round/ (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Davis, G.A.; Makdissi, M.; Bloomfield, P.; Clifton, P.; Cowie, C.; Echemendia, R.; Falvey, E.C.; Fuller, G.W.; Green, G.A.; Harcourt, P.; et al. Concussion Guidelines in National and International Professional and Elite Sports. Neurosurgery. Neurosurgery 2020, 87, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Football Association. If in Doubt, Sit Them Out: English FA Concussion Guidelines; The FA.: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.englandfootball.com/concussion (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Rugby Football Union. Headcase: Extended Guidelines; RFU: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://rfu.widen.net/s/rqg8bssfgb/headcase_extended-guidelines_aug_2023 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- British Cycling. Concussion Guidelines; British Cycling: Manchester, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.britishcycling.org.uk/zuvvi/media/media/press/British_Cycling_-_Concussion_Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- England Hockey. Concussion Policy; England Hockey: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://assets-eu-01.kc-usercontent.com/d66c6a48-e05a-01b8-e0ec-59ee93833239/cb563990-892c-44e6-b943-dcd2606c1073/Hockey%20Concussion%20Policy%20Nov%202018%20v2.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.; Zarin, L.E.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist SECTION. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squash Info. Women’s PSA World Squash Rankings. Available online: https://www.squashinfo.com/rankings/women (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Squash Info. Men’s PSA World Squash Rankings. Available online: https://www.squashinfo.com/rankings/men (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- World Squash Federation. WSF Information: Member Nations. World Squash. Available online: https://www.worldsquash.org/wsf-information/member-nations-2-2/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Squash Canada. Squash Canada Concussion Protocol; Squash Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://squash.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Squash-Canada-Concussion-Protocol-Approved-06-09-191.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Parachute Canada. Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport, 2nd ed.; Parachute Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://parachute.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Concussion-Guideline-2024.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Sport and Recreation Alliance. UK Concussion Guidelines for Grassroots; UK Government: London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://sportandrecreation.org.uk/files/uk-concussion-guidelines-for-grassroots-non-elite-sport---november-2024-update-061124084139.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- ACC. Sport Concussion in New Zealand: National Guidelines; ACC: Wellington, New Zealand, 2024; Available online: https://sportnz.org.nz/media/50udkfu5/acc_cis-guidelines_jan2024.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Aspetar Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Hospital. Sports Concussion. Patient Information, Common Sports Injuries—Head. Aspetar. Available online: https://www.aspetar.com/en/patient-information/common-sports-injuries/head/sports-concussion (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Sportscotland. If in Doubt, Sit Them Out. In Scottish Sports Concussion Guidance: Grassroots Sport and General Public; Sportscotland: Glasgow, UK, 2024; Available online: https://sportscotland.org.uk/media/ztfnilyc/concussion-guidance-2024.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heads Up: Concussion and Head Injury Awareness; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, n.d. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/heads-up/index.html (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Parachute Canada. Concussion Collection: Concussion Harmonization Project; Parachute Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://parachute.ca/en/professional-resource/concussion-collection/concussion-harmonization-project/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- World Rugby. Laws of the Game Rugby Union; World Rugby: Dublin, Ireland, 2025; Available online: https://passport.world.rugby/media/k2ekxsmo/2501en-world-rugby-laws-2025-compressed.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Scullion, E.; Heron, N. A Scoping Review of Concussion Guidelines in Amateur Sports in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echemendia, R.J.; Burma, J.S.; Bruce, J.M.; Davis, G.A.; Giza, C.C.; Guskiewicz, K.M.; Naidu, D.; Black, A.M.; Broglio, S.; Kemp, S.; et al. Acute evaluation of sport-related concussion and implications for the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT6) for adults, adolescents and children: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliason, P.H.; Galarneau, J.-M.; Kolstad, A.T.; Pankow, M.P.; West, S.W.; Bailey, S.; Miutz, L.; Black, A.M.; Broglio, S.P.; Davis, G.A.; et al. Prevention strategies and modifiable risk factors for sport-related concussions and head impacts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | Governing Body | Squash-Specific Concussion Policy | National Sports Related Concussion Policy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | Belgian Squash Federation | No | No |

| Canada | Squash Canada | Yes—Squash Canada Concussion Protocol [29] | Yes—Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport [30] |

| Colombia | Colombian Squash Federation | No | No |

| Egypt | Egyptian Squash Federation | No | No |

| England | England Squash | No | Yes—UK Concussion Guidelines for Non-Elite (Grassroots) Sport November 2024 [31] |

| France | French Squash Federation | No | No |

| Germany | German Squash Association | No | No |

| Hong Kong | Squash Association of Hong Kong, China | No | No |

| Hungary | Hungarian Squash Association | No | No |

| India | Squash Rackets Federation of India | No | No |

| Japan | Japan Squash Association | No | No |

| Malaysia | Squash Racquets Association of Malaysia (SRAM) | No | No |

| Mexico | Mexico Squash Association | No | No |

| New Zealand | Squash New Zealand | No | Yes—Sport Concussion in New Zealand: National Guidelines [32] |

| Peru | Peruvian Squash Federation | No | No |

| Qatar | Qatar Squash Federation | No | Yes—The Aspetar Sport Related Concussion Programme [33] |

| Scotland | Scottish Squash | No | Yes—If in doubt, sit them out. Scottish Sports Concussion Guidance: grassroots sport and general public [34] |

| Spain | Spanish Squash Federation | No | No |

| Switzerland | Swiss Squash | No | No |

| United States | US Squash | No | Guidance available on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website [35] |

| Wales | Squash Wales | No | UK Concussion Guidelines for Non-Elite (Grassroots) Sport November 2024 [31] |

| Country | Sideline Assessment and Recommendation of Screening Tools | List of Signs and Symptoms of Concussion | Immediate Removal of Player with Suspected Concussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | N/A * | N/A | N/A |

| Canada | Yes—recommends CRT5, SCAT5 and Child SCAT5 | Yes | Yes |

| Colombia | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Egypt | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| England | No | Yes | Yes |

| France | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Germany | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hong Kong | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hungary | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| India | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Japan | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Malaysia | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mexico | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| New Zealand | No | Yes | Yes |

| Peru | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Qatar | Yes—recommends CRT6, SCAT6 and SCOAT6 | Yes | Yes |

| Scotland | No | Yes | Yes |

| Spain | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Switzerland | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| United States | No | Yes | Yes |

| Wales | No | Yes | Yes |

| Country | Initial Period of Relative Rest (hours) | Guidance on Return to Play | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | N/A ** | N/A | N/A |

| Canada | 24–48 | Yes | Return-to-School Strategy Squash-Specific Return-to-Sport Strategy |

| Colombia | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Egypt | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| England | 24 | Yes | Graduated return to activity (education/work) and sport programme |

| France | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Germany | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hong Kong | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hungary | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| India | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Japan | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Malaysia | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mexico | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| New Zealand | 24–48 | Yes | Includes a return to work/sport guide |

| Peru | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Qatar | Yes | Return to sport/learning guidance | |

| Scotland | 24–48 | Yes | Return to work/play guidance |

| Spain | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Switzerland | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| United States | Not explicitly stated | Yes | 6-step return to play progression Focus on children |

| Wales | 24 | Yes | Graduated return to activity (education/work) and sport programme |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mangan, N.; Heron, N. A Scoping Review of Sport National Concussion Guidelines in Squash. Sports 2025, 13, 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13090325

Mangan N, Heron N. A Scoping Review of Sport National Concussion Guidelines in Squash. Sports. 2025; 13(9):325. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13090325

Chicago/Turabian StyleMangan, Nina, and Neil Heron. 2025. "A Scoping Review of Sport National Concussion Guidelines in Squash" Sports 13, no. 9: 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13090325

APA StyleMangan, N., & Heron, N. (2025). A Scoping Review of Sport National Concussion Guidelines in Squash. Sports, 13(9), 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13090325