Urinary Incontinence in Young Gymnastics Athletes: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: adolescent and adult female gymnasts.

- Concept: evaluation of stress urinary incontinence in gymnasts.

- Context: to assess incontinence in a training environment, in a sports context.

2.2. Evidence Sources

2.3. Research Strategy

2.4. Evidence Selection

2.5. Analysis and Results Presentation

3. Results

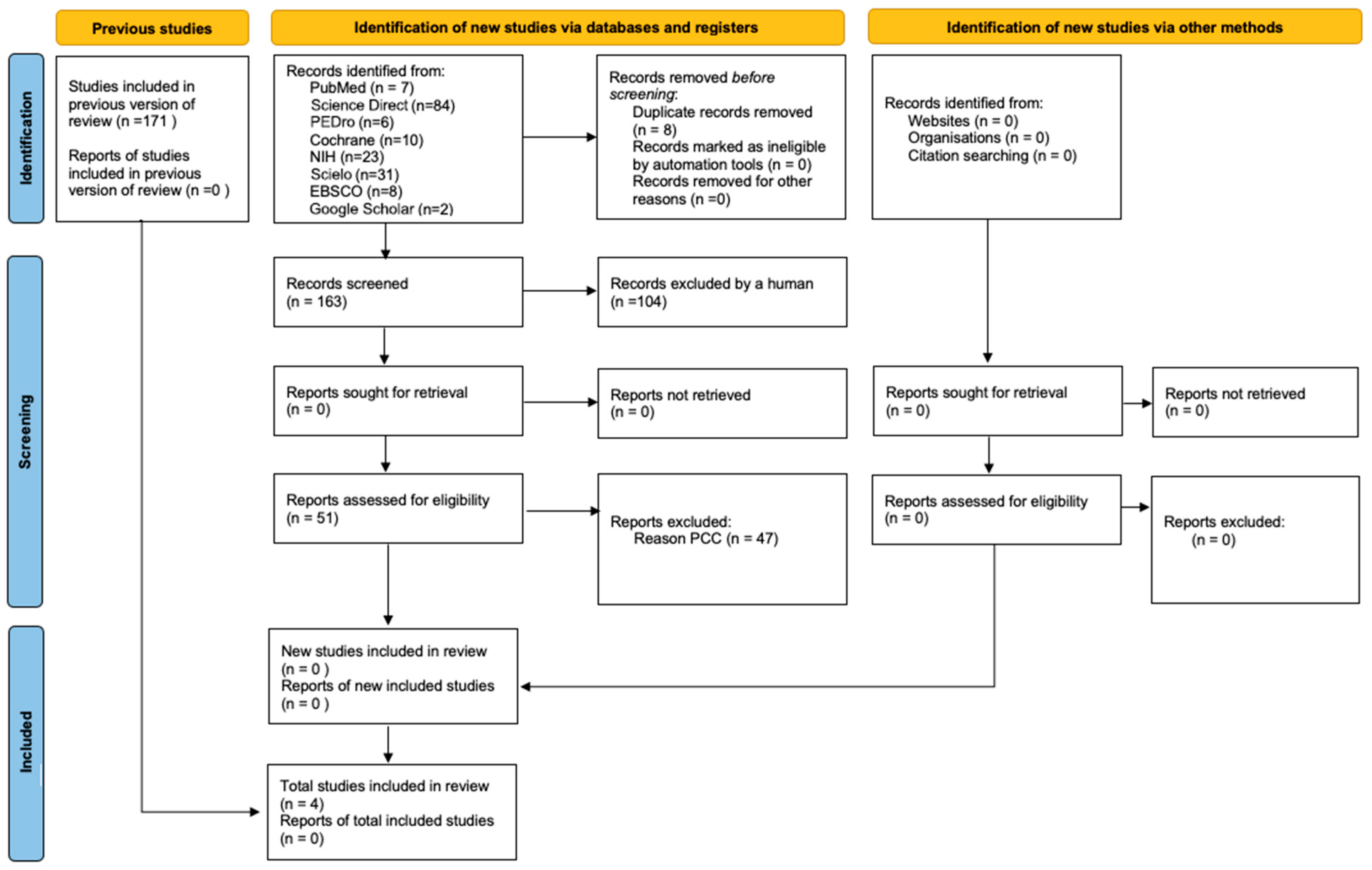

3.1. Selection of Evidence Sources

3.2. Types of Study

3.3. Participant Characteristics

3.4. Intervention

3.5. Assessment Tools

3.6. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haylen, B.T.; De Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011, 29, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’ANcona, C.; Haylen, B.; Oelke, M.; Abranches-Monteiro, L.; Arnold, E.; Goldman, H.; Hamid, R.; Homma, Y.; Marcelissen, T.; Rademakers, K.; et al. The International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms and dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2019, 38, 433–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedicação, A.; Haddad, M.; Saldanha, M.; Driusso, P. Comparação da qualidade de vida nos diferentes tipos de incontinência urinária feminina. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2009, 13, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aoki, Y.; Brown, H.W.; Brubaker, L.; Cornu, J.N.; Daly, J.O.; Cartwright, R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milsom, I.; Altman, D.; Cartwright, R.; Lapitan, M.C.; Nelson, R.; Sillén, U.; Tikkinen, K. Epidemiology of Urinary Incon-tinence (UI) and other Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) and Anal Incontinence (AI). In Incontinence: 5th International Consultation on Incontinence, Paris, February 2012, 5th ed.; Abrams, P., Cardozo, L., Khoury, S., Wein, A.J., Eds.; ICUD-EAU: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 15–107. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, S.; Dinis, P.; Rolo, F.; Lunet, N. Prevalence, treatment and known risk factors of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in the non-institutionalized Portuguese population. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2009, 20, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preda, A.; Moreira, S. Incontinência Urinária de Esforço e Disfunção Sexual Feminina: O Papel da Reabilitação do Pavimento Pélvico. Acta Médica Port. 2019, 32, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benício, C.D.A.V.; Luz, M.H.B.A.; De Oliveira Lopes, M.V.; De Carvalho, N.A.R. Incontinência Urinária: Prevalência e Fatores de Risco em Mulheres em uma Unidade Básica de Saúde. Estima 2016, 14, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Lopes, M.V.; Higa, R. Restrições causadas pela incontinência urinária à vida da mulher. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2006, 40, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, P.; Cardozo, L.; Fall, M.; Griffiths, D.; Rosier, P.; Ulmsten, U.; van Kerrebroeck, P.; Victor, A.; Wein, A. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation sub-committee of the international continence society. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 187, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.B.A.; Barra, A.A.; Saltiel, F.; Silva-Filho, A.L.; Fonseca, A.M.R.M.; Figueiredo, E.M. Urinary incontinence and other pelvic floor dysfunctions in female athletes in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bø, K. Urinary Incontinence, Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, Exercise and Sport. Sports Med. 2004, 34, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, I.E.; Shaw, J.M. Physical activity and the pelvic floor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.M.; Nygaard, I.E. Role of chronic exercise on pelvic floor support and function. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2017, 27, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nygaard, I.; DeLancey, J.; Arnsdorf, L.; Murphy, E. Exercise and incontinence. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1995, 33, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carls, C. The prevalence of stress urinary incontinence in high school and college-age female athletes in the midwest: Implications for education and prevention. Urol. Nurs. 2007, 27, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Bø, K.; Borgen, J.S. Prevalence of stress and urge urinary incontinence in elite athletes and controls. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1797–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thyssen, H.H.; Clevin, L.; Olesen, S.; Lose, G. Urinary Incontinence in Elite Female Athletes and Dancers. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2002, 13, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliasson, K.; Larsson, T.; Mattsson, E. Prevalence of stress incontinence in nulliparous elite trampolinists. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2002, 12, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.; Srivastava, K.; Ochuba, O.; Ruo, S.W.; Alkayyali, T.; Sandhu, J.K.; Waqar, A.; Jain, A.; Poudel, S. Stress Urinary Incontinence Among Young Nulliparous Female Athletes. Cureus 2021, 13, e17986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, A.P.; Marcondes, F.K. Estresse, ciclo reprodutivo e sensibilidade cardíaca às catecolaminas. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2002, 38, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guezennec, C.; Oliver, C.; Lienhard, F.; Seyfried, D.; Huet, F.; Pesce, G. Hormonal and metabolic response to a pistol-shooting competition. Sci. Sports 1992, 7, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, M.C.D.; Bø, K. High level rhythmic gymnasts and urinary incontinence: Prevalence, risk factors, and influence on performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaug, K.L.; Engh, M.E.; Frawley, H.; Bø, K. Urinary and anal incontinence among female gymnasts and cheerleaders—Bother and associated factors. A cross-sectional study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 33, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Roza, T.M.; Brandão, S.M.; Mascarenhas, T.; Jorge, R.N.; Duarte, J.A. Volume of Training and the Ranking Level Are Associated With the Leakage of Urine in Young Female Trampolinists. Am. J. Ther. 2015, 25, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, T.H.; Church, J.M.; Fleshman, J.W.; Kane, R.L.; Mavrantonis, C.; Thorson, A.G.; Wexner, S.D.; Bliss, D.; Lowry, A.C. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 1999, 42, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterill, N.P.; Norton, C.P.; Avery, K.N.L.; Abrams, P.; Donovan, J.L.P. Psychometric Evaluation of a New Patient-Completed Questionnaire for Evaluating Anal Incontinence Symptoms and Impact on Quality of Life: The ICIQ-B. Dis. Colon Rectum 2011, 54, 1235–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Maria, U.P.; Juzwiak, C.R. Cultural adaptation and validation of the low energy availability in females questionnaire (LEAF-Q). Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2021, 27, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.J.; Nattiv, A.; Joy, E.; Misra, M.; I Williams, N.; Mallinson, R.J.; Gibbs, J.C.; Olmsted, M.; Goolsby, M.; Matheson, G.; et al. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, California, May 2012 and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, S.; Reinhold, E.J.; Pearce, G.S. The Beighton Score as a measure of generalised joint hypermobility. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegel, M.; Meston, C.; Rosen, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): Cross-Validation and Development of Clinical Cutoff Scores. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2005, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, K.M.; Da Roza, T.; Da Silva, L.L.; Wolpe, R.E.; Da Silva Honório, G.J.; Da Luz, S.C. Female sexual function and urinary incontinence in nulliparous athletes: An exploratory study. Phys. Ther. Sport 2018, 33, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bø, K. Physiotherapy management of urinary incontinence in females. J. Physiother. 2020, 66, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin, C.; Hay-Smith, E.J.C.; Mac Habée-Séguin, G. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 5, 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Women: Management. In NICE Guideline; NICE: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tamanini, J.T.N.; Dambros, M.; D’ANcona, C.A.L.; Palma, P.C.R.; Rodrigues Netto, N., Jr. Validação para o português do “International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Short Form” (ICIQ-SF). Rev. Saude Publica 2004, 38, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboia, D.M.; Firmiano, M.L.V.; Bezerra, K.d.C.; Neto, J.A.V.; Oriá, M.O.B.; Vasconcelos, C.T.M. Impacto dos tipos de incontinência urinária na qualidade de vida de mulheres. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2017, 51, e03266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, K.; Donovan, J.; Peters, T.J.; Shaw, C.; Gotoh, M.; Abrams, P. ICIQ: A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2004, 23, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bø, K.; Nygaard, I.E. Is Physical Activity Good or Bad for the Female Pelvic Floor? A Narrative Review. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seegmiller, J.G.; McCaw, S.T. Ground Reaction Forces Among Gymnasts and Recreational Athletes in Drop Landings. J. Athl. Train. 2003, 38, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Database | Search Strategy | Filters Used |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“woman” OR “female” OR “athlete”) AND (“gymnastic” OR “trampoline” OR “acrobatic” OR “high impact sport”) AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders” OR “loss of urine” OR “urine leakage”) AND (“prevalence” OR “treatment” OR “knowledge” OR “impact” OR “quality of life” OR “prevention”) | Published between 2012 and 2023 Full text available Study type: journal article, clinical trial, randomised controlled trial, books and documents Language: English, Portuguese Age: adolescents (13–18 years), young adults (19–24 years), adults (19–44 years) Sex: female |

| Cochrane | (“gymnastic” OR “trampolim” OR “acrobatic” OR “high impact sport”) AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders”) | Published between 2012 and 2023 Language: English Publication type: Clinical trials |

| Science Direct | (“gymnastic” OR “trampolim” OR “acrobatic” OR “high impact sport”) AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders”). | Published between 2012 and 2023 Publication type: research articles, book chapters Access: free access, open archive |

| Scielo | (“gymnastic” OR “trampolim” OR “acrobatic” OR “high impact sport”) AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders”) | Published between 2012 and 2023 Language: English, Portuguese Type of literature: articles |

| EBSCO | (“gymnastic” OR “trampolim” OR “acrobatic” OR “high impact sport”) AND (“urinary incontinence” OR “stress urinary incontinence” OR “pelvic floor disorders”) | Published between 2012 and 2023 References available Type of publication: academic journal articles, reports, books |

| PEDro | “incontinence. Subdisciplina: “sports” | Published from 2012 onwards Method: clinical trial |

| NIH | “urinary incontinence”. Outros termos: “sport” | Articles published from 2012 onwards Study type: clinical trial, observational study Status: completed and closed Expanded access: available Study with results Age: children and adults Sex: female |

| Authors /Year | Study | Objectives | Participants | Assessment Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeida et al. (2016) [11] | Cross-sectional study | To investigate the occurrence of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) symptoms among athletes and non-athletes. To investigate the influence of sport on the occurrence and severity of urinary dysfunction. | n = 163 Athletes (n = 67): artistic gymnastics and trampoline (n = 9) Non-athletes (n = 96) 15–29 years BMI athletes: 21.7 (±2.6) BMI non-athletes: 20.9 (±3.9) Nulliparous IU (gymnasts): 88.9% IUE (gymnasts): 87.5% | ICIQ-UI-SF FISI Criteria Rome III FSFI ICIQ-VS | Pelvic floor dysfunctions Influence of modality Impact on quality of life Attitude towards UI |

| Da Roza et al. (2015) [27] | Cohort study | To investigate the association between UI severity and training volume and athletic performance in young female nulliparous trampolinists. | n = 22 Trampolinists/ National level 14–25 years BMI: 20.4 (±1.3) Nulliparous SUI: 72.7% | ICIQ-UI-SF | Prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) Association between UI severity and training volume Impact on quality of life and athletic performance |

| Gram et Bø, (2020) [25] | Cross-sectional study | To investigate the prevalence and risk factors of UI in rhythmic gymnasts and the impact of UI on sports performance. Evaluate PFM knowledge and PFM training. | n = 107 Rhythmic gymnastics International level 12–21 years BMI: 18.5 (±5.3) Nulliparous 65.4% menarche UI: 31.8% SUI: 61.8% UI: 8.8% UI: 17.6% Other UI: 11.8% | ICIQ-UI-SF “Triad-specific self-report questionnaire” LEAF-SF Beighton score | UI prevalence Prevalence of type of UI Impact of UI on athletic performance Knowledge about PFM and its training |

| Skaug et al., (2022) [26] | Cross-sectional study | To investigate the prevalence and risk factors of UI and anal incontinence (AI) in high-performance female artistic gymnasts (AG), team gymnasts (TG) and female cheerleaders. To investigate the impact of UI/IA on sports performance. To assess the athletes’ knowledge of PFM. | n = 319 Artistic gymnastics (n = 68), Team gymnastics (n = 116), Cheerleading (n = 135) National and international level 12–36 years BMI: 21.7 (±2.7) Nulliparous 92.2% menarcas IU: AG 70.6%, TG 83.6% IUE: AG 70.6%, TG 80.2% IUU: AG 8.8%, TG 12.9% | ICIQ-UI-SF ICIQ-B LEAF-Q | Prevalence of UI and AI Prevalence of type of UI Impact on athletic performance Knowledge of UI |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Higounenc, A.; Carvalhais, A.; Vieira, Á.; Lopes, S. Urinary Incontinence in Young Gymnastics Athletes: A Scoping Review. Sports 2025, 13, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13090319

Higounenc A, Carvalhais A, Vieira Á, Lopes S. Urinary Incontinence in Young Gymnastics Athletes: A Scoping Review. Sports. 2025; 13(9):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13090319

Chicago/Turabian StyleHigounenc, Alice, Alice Carvalhais, Ágata Vieira, and Sofia Lopes. 2025. "Urinary Incontinence in Young Gymnastics Athletes: A Scoping Review" Sports 13, no. 9: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13090319

APA StyleHigounenc, A., Carvalhais, A., Vieira, Á., & Lopes, S. (2025). Urinary Incontinence in Young Gymnastics Athletes: A Scoping Review. Sports, 13(9), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13090319