The Mediating Role of Mental Toughness in the Relationship Between Burnout and Perceived Stress Among Hungarian Coaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Coach Burnout

2.2.2. Mental Toughness

2.2.3. Perceived Stress

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Comparison of Burnout Values with International Data

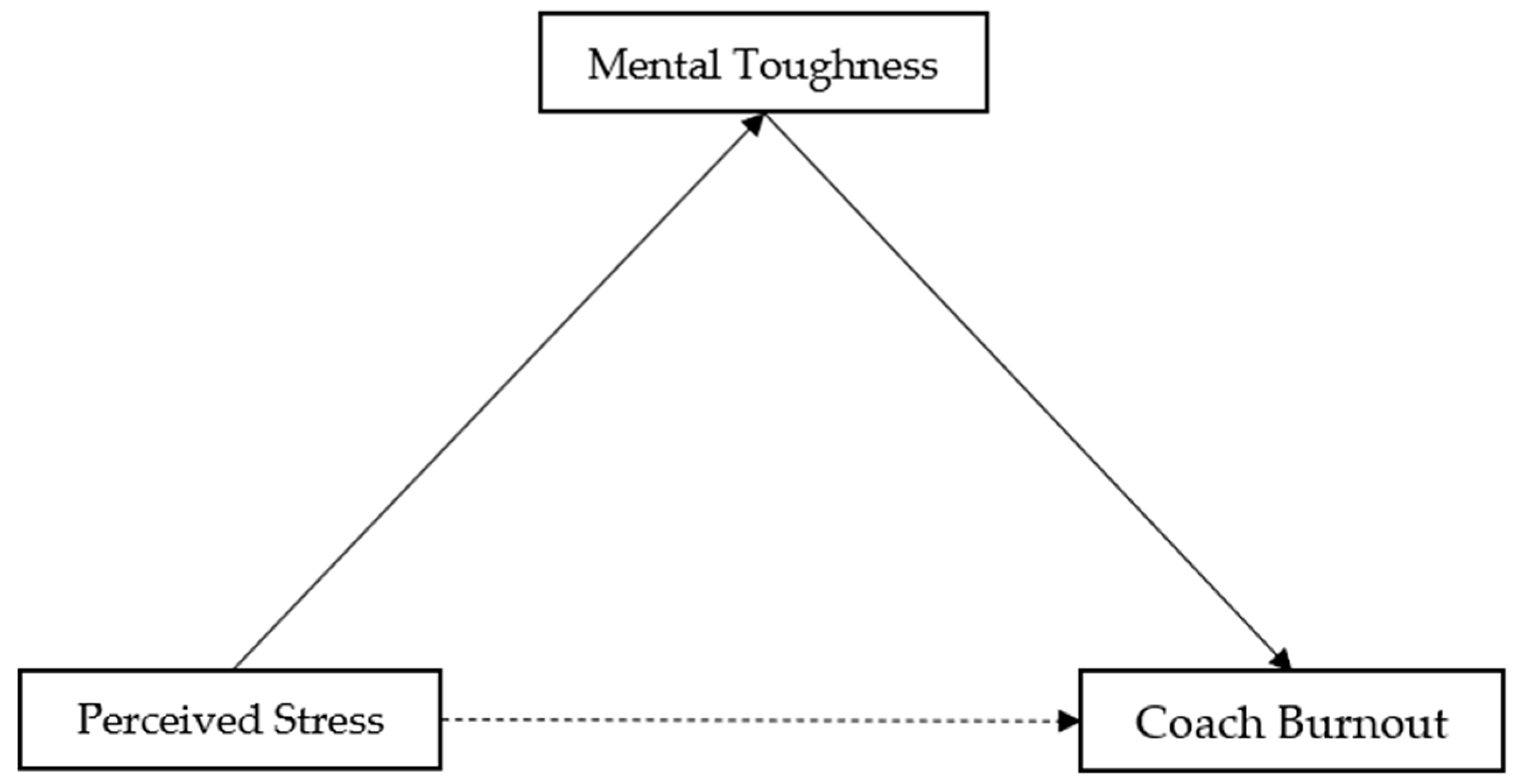

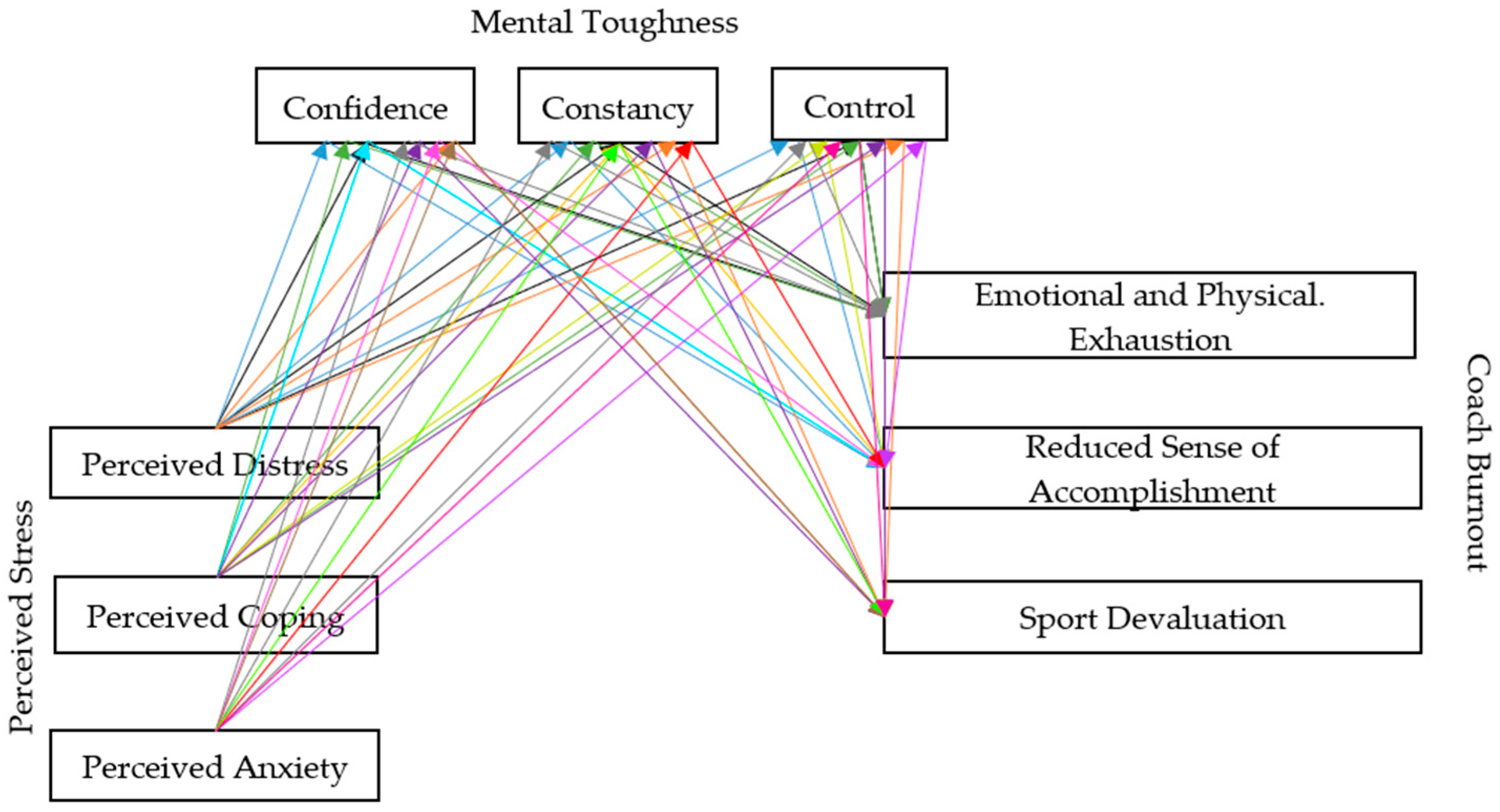

3.4. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. First Hypothesis

4.2. Second Hypothesis

4.3. Third Hypothesis

4.4. Limits and Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBQ | Coach Burnout Questionnaire |

| SMTQ | Sports Mental Toughness Questionnaire |

| PSS | Perceived Stress Scale |

| PSS | Perceived Stress |

| CB | Coach Burnout |

| MT | Mental Toughness |

| PD | Perceived Distress |

| PC | Perceived Coping |

| PA | Perceived Anxiety |

| EPE | Emotional and Physical Exhaustion |

| RSA | Reduced Sense of Accomplishment |

| SD | Sport Devaluation |

References

- Walsh, J. Becoming an Effective Youth Sports Coach. In Sport Pedagogy; Armour, K., Ed.; Pearson Education Ltd.: Harlow, UK, 2011; pp. 287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, D. Your role as a youth sports coach. In Handbook for Youth Sport Coaches; Seefeldt, V., Ed.; American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance: Reston, VA, USA, 1987; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mitten, M.J. The coach and the safety of athletes: Ethical and legal issues. In The Ethics of Coaching Sports; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman-Lamb, N.; Silva, D. “The coaches always make the health decisions”: Conflict of interest as exploitation in power five college football. SSM-Qual. Res. Health 2024, 5, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, J. Sport Coaching Research and Practice: Ontology, Interdisciplinarity and Critical Realism; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. Stress Without Distress; Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, C.C.; Rutter, L.A.; Brown, T.A. Chronic environmental stress and the temporal course of depression and panic disorder: A trait-state-occasion modeling approach. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2015, 125, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. Stress without Distress. In Psychopathology of Human Adaptation; Serban, G., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1976; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, H.; Kenttä, G.; Hassmén, P. Athlete burnout: An integrated model and future research directions. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2011, 4, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixdorf, I.; Beckmann, J.; Nixdorf, R. Psychological predictors for depression and burnout among German junior elite athletes. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, N. How to solve the Mind-Body Problem. J. Conscious. Stud. 2000, 7, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, H.; Skoog, T. The mediational role of perceived stress in the relation between optimism and burnout in competitive athletes. Anxiety Stress Coping 2011, 25, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; González, A.D.; Gabani, F.L.; De Andrade, S.M. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raedeke, T.D. Coach Commitment and Burnout: A One-Year Follow-Up. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2004, 16, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, M.; Lemyre, P.-N.; Kenttä, G. The process of burnout among professional sport coaches through the lens of self-determination theory: A qualitative approach. Sports Coach. Rev. 2014, 3, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.S.; Weiss, M.R. Relationships among Coach Burnout, Coach Behaviors, and Athletes’ Psychological Responses. Sport Psychol. 2000, 14, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.S.; Lavallee, D.; Spray, C.M. Coping with the effects of fear of failure: A preliminary investigation of young elite athletes. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2009, 3, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovzhik, L.M.; Bochaver, K.A.; Reznichenko, S.I.; Bondarev, D.V. Sport coaches burnout as a threat to professional success, mental health and Well-Being. Clin. Psychol. Spec. Educ. 2021, 10, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccese, T.M.; Mayerberg, C.K. Gender differences in perceived burnout of college coaches. J. Sport Psychol. 1984, 6, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, B.C.; Gill, D.L. An examination of Personal/Situational variables, stress appraisal, and burnout in collegiate Teacher-Coaches. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1993, 64, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, B.C.; Eklund, R.C.; Ritter-Taylor, M. Stress and Burnout among Collegiate Tennis Coaches. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1999, 21, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, D.L.; Judd, M.R. Gender Differences in Burnout among Coaches of Women’s Athletic Teams at 2-Year Colleges. Sociol. Sport J. 1993, 10, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vealey, R.S.; Udry, E.M.; Zimmerman, V.; Soliday, J. Intrapersonal and situational predictors of coaching burnout. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1992, 14, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş, Ö.; Karakoç, B.; Karakoç, Ö. Analysis of burnout levels of judo coaches in the COVID-19 Period: Mixed method. J. Educ. Issues 2021, 7, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altfeld, S.; Kellmann, M. Are German coaches highly exhausted? A study of differences in personal and environmental factors. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2015, 10, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencay, S.; Gencay, O.A. Burnout among Judo Coaches in Turkey. J. Occup. Health 2011, 53, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinauskas, R.; Malinauskiene, V.; Dumciene, A. Burnout and Perceived Stress among University Coaches in Lithuania. J. Occup. Health 2010, 52, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singe, S.M.; Cairns, A.; Eason, C.M. Age, sex, and years of experience: Examining burnout among secondary school athletic trainers. J. Athl. Train. 2022, 57, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinauskas, R.; Malinauskiene, V. Characteristics of Stress and Burnout among Lithuanian University Coaches: A Pre-Pandemic Coronavirus and Post-Pandemic Period Comparison. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusoga, P.; Bentzen, M.; Kentta, G. Coach burnout: A scoping review. Int. Sport Coach. J. 2019, 6, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connaughton, D.; Wadey, R.; Hanton, S.; Jones, G. The development and maintenance of mental toughness: Perceptions of elite performers. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 26, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, P.J.; Earle, K.; Sewell, D. Mental Toughness: The Concept and Its Measurement. In Solutions in Sport Psychology; Cockerill, I., Ed.; Thomson: London, UK, 2002; pp. 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- St Clair-Thompson, H.; Devine, L. Mental toughness in higher education: Exploring the roles of flow and feedback. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 43, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denovan, A.; Dagnall, N.; Drinkwater, K. Examining what Mental Toughness, Ego Resiliency, Self-efficacy, and Grit measure: An exploratory structural equation modelling bifactor approach. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 22148–22163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.; Zaichkowsky, L. Explanatory Style among Elite Ice Hockey Athletes. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1998, 87, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Hanton, S.; Connaughton, D. What is this thing called mental toughness? An investigation of elite sport performers. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2002, 14, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucciardi, D.F.; Hanton, S.; Gordon, S.; Mallett, C.J.; Temby, P. The concept of mental toughness: Tests of dimensionality, nomological network, and traitness. J. Personal. 2014, 83, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gucciardi, D.F. Commentary: Mental Toughness and Individual Differences in learning, educational and work performance, Psychological well-being, and Personality: A Systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.; Lu, F.J.H.; Gill, D.L.; Hsu, Y.-W.; Wong, T.-L.; Kuan, G. Effects of mental toughness on athletic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 22, 1317–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X.; Fan, Y.; Mao, Y.; Wang, P. Effects and mechanisms of social support on the adolescent athletes engagement. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1987, 57, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Best, S.; Meerstetter, F.; Walter, M.; Ludyga, S.; Brand, S.; Bianchi, R.; Madigan, D.J.; Isoard-Gautheur, S.; Gustafsson, H. Effects of stress and mental toughness on burnout and depressive symptoms: A prospective study with young elite athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, M.; Gerber, M. Does mental toughness buffer the relationship between perceived stress, depression, burnout, anxiety, and sleep? Int. J. Stress Manag. 2018, 26, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, F.; St Clair-Thompson, H.; Postlethwaite, A. Mental toughness and perceived stress in police and fire officers. Polic. Int. J. 2018, 41, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Kalak, N.; Lemola, S.; Clough, P.J.; Perry, J.L.; Pühse, U.; Elliot, C.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Brand, S. Are adolescents with high mental toughness levels more resilient against stress? Stress Health 2012, 29, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Feldmeth, A.K.; Lang, C.; Brand, S.; Elliot, C.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Pühse, U. The Relationship between Mental Toughness, Stress, and Burnout among Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study with Swiss Vocational Students. Psychol. Rep. 2015, 117, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulus, D.R.; Sargeant, J.; Zarate, D.; Griffiths, M.D.; Stavropoulos, V. Burnout profiles among esports players: Associations with mental toughness and resilience. J. Sports Sci. 2024, 42, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, M.; Gygax, B.; Cody, R. Coach-athlete relationship and burnout symptoms among young elite athletes and the role of mental toughness as a moderator. Sports Psychiatry 2024, 3, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Nicholls, A.R. Mental toughness and burnout in junior athletes: A longitudinal investigation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 32, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Yang, S.-Y. The Effect of social support on athlete burnout in weightlifters: The mediation effect of mental toughness and sports motivation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 649677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Tao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, H. Emotional Intelligence and Burnout among Adolescent Basketball Players: The Mediating Effect of Emotional Labor. Sports 2024, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levillain, G.; Vacher, P.; de Roten, Y.; Nicolas, M. Influence of Defense Mechanisms on Sport Burnout: A Multiple Mediation Analysis Effects of Resilience, Stress and Recovery. Sports 2024, 12, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raanes, E.F.W.; Hrozanova, M.; Moen, F. Identifying Unique Contributions of the Coach–Athlete Working Alliance, Psychological Resilience and Perceived Stress on Athlete Burnout among Norwegian Junior Athletes. Sports 2019, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, F.; Hrozanova, M.; Stiles, T.C.; Stenseng, F. Burnout and Perceived Performance Among Junior Athletes—Associations with Affective and Cognitive Components of Stress. Sports 2019, 7, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.S.; Ostrow, A.C. Coach and Athlete Burnout: The Role of Coaches’ Decision-making Style. In Sports and Athletics Developments; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bíró, E.; Papp-Bata, Á.; Pucsok, J.M.; Rátgéber, L.; Barna, L.; Németh, K.; Nagy, B.F.; Balogh, L. Hungarian Adaptation of the Coach Burnout Questionnaire. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2025, 25, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torma, E.P.; Papp-Bata, Á.; Balogh, L. Breakable performance—The role of mental toughness in elite sport, international outlook. Stad. Hung. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheard, M.; Golby, J.; Van Wersch, A. Progress toward Construct Validation of the Sports Mental Toughness Questionnaire (SMTQ). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 25, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. Perceived stress scale. In Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists; PsycTESTS Dataset; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauder, A.; Konkoly, B.T. AZ ÉSZLELT STRESSZ KÉRDŐÍV (PSS) MAGYAR VERZIÓJÁNAK JELLEMZŐI. (Hungarian Adaptation of the Perceived Stress Scale). Mentálhig. Pszichoszomatika 2006, 7, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeer, I.; Lyle, J. Coaching experience: Examining its role in coaches’ decision making. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 7, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilo, R.A.; Hassmén, P. Burnout and turnover intentions in Australian coaches as related to organisational support and perceived control. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2016, 11, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundkvist, E.; Gustafsson, H.; Davis, P.A. What is missing and why it is missing from coach burnout research. In The Psychology of Effective Coaching and Management; Davis, P.A., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 407–428. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, N.C.H.; Zhao, J.H. Demographic, personal, and situational variables associated with burnout in Singaporean coaches. Sports Coach. Rev. 2018, 8, 262–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, B. The Impact of Entrapment: Exploring the Role of Entrapment in Coach Burnout. Ph.D. Thesis, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK, 2022. Available online: https://britishcanoeingawarding.org.uk/wp-content/files/Exploring_Coach_Burnout_-_Benjamin_Woodruff.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Holden, C.L.; Jeanfreau, M.M. Are Perfectionistic Standards Associated with Burnout? Multidimensional Perfectionism and Compassion Experiences Among Professional MFTs. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2023, 45, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtulget, E.; Çepikkurt, F. An Investigation of Perfectionism and Mental Toughness in Athletes. Int. J. Recreat. Sports Sci. 2024, 8, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Stress, Culture, and Community; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lantos, T.; McNally, R.J.Q.; Nyári, T.A. Patterns of suicide deaths in Hungary between 1995 and 2017. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.D.; De Neve, J.-E.; Aknin, L.B.; Wang, S. World Happiness Report 2025; Wellbeing Research Centre, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hertting, K.; Wagnsson, S.; Grahn, K. Perceptions of Stress of Swedish Volunteer Youth Soccer Coaches. Sports 2020, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.A.; Walker, L.F.; Hall, E.E. Effects of workplace stress, perceived stress, and burnout on collegiate coach mental health outcomes. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 974267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoğlu, H.E.; Cengiz, C.; Hazar, Z.; Erdeveciler, Ö.; Balcı, V. The impact of mental toughness on resilience and well-being: A comparison of hearing-impaired and non-hearing-impaired athletes. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 34, e2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, T.A.; Deiters, J.; Harmison, R.J. Mental toughness, social support, and athletic identity: Moderators of the life stress–injury relationship in collegiate football players. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2013, 3, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N = 333 |

| Age | 43.08 ± 12.95 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 108 (32%) |

| Male | 225 (68%) |

| Level | |

| First Class and National Team | 164 (49%) |

| Lower Classes | 169 (51%) |

| Coaching experience | |

| Debutant (1–5 years) | 75 (23%) |

| Average experience (6–10 years) | 81 (24%) |

| Experienced (+10 years) | 177 (53%) |

| Aerobics | 5 | Jiu-Jitsu | 1 |

| American Football | 1 | Judo | 20 |

| Athletics | 13 | Karate | 3 |

| Badminton | 1 | Orienteering | 1 |

| Basketball | 25 | Pentathlon | 2 |

| Beach Volleyball | 1 | Personal Training | 3 |

| Boxing | 4 | Rhythmic Gymnastics | 6 |

| Canoeing | 11 | Sailing | 7 |

| Cycling | 3 | Speed skating | 3 |

| Dance | 3 | Swimming | 12 |

| Fencing | 12 | Synchronized Swimming | 3 |

| Figure Skating | 1 | Table Tennis | 5 |

| Football | 36 | Tennis | 2 |

| Futsal | 6 | Triathlon | 10 |

| Gymnastics | 5 | Volleyball | 24 |

| Handball | 95 | Water Polo | 7 |

| Ice Hockey | 1 | Wrestling | 1 |

| Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Burnout | 3.91 | 0.60 | −0.70 | 0.70 |

| Overall Mental Toughness | 44.69 | 5.19 | −0.65 | 1.24 |

| Overall Stress | 21.09 | 7.54 | 0.51 | 0.42 |

| Authors | Country | International Studies Mean | International Studies SD | Present Study Mean | Present Study SD | Report | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional and Physical Exhaustion | |||||||

| Harris and Ostrow, 2008 [56] | USA | 2.73 | 0.98 | 3.98 | 0.78 | greater p < 0.001 | 0.94 |

| Kilo and Hassmén, 2016 [67] | Australia | 2.39 | 0.95 | 0.93 | |||

| Lundkvist et al., 2016 [68] | Sweden | 2.12 | 0.05 | 0.90 | |||

| Ong and Zhao, 2018 [69] | Singapore | 2.35 | 0.82 | 0.91 | |||

| Woodruff, 2022 [70] | United Kingdom | 2.23 | 0.95 | 0.93 | |||

| Malinauskas and Malinauskiene, 2023 [29] | Lithuania | 2.16 | 0.62 | 0.76 | |||

| Bíró et al., 2025 [57] | Hungary | 2.04 | 1.10 | 0.89 | |||

| Reduced Sense of Accomplishment | |||||||

| Harris and Ostrow, 2008 [56] | USA | 2.73 | 0.67 | 3.82 | 0.64 | greater p < 0.001 | 0.81 |

| Kilo and Hassmén, 2016 [67] | Australia | 2.02 | 0.62 | 0.80 | |||

| Ong and Zhao, 2018 [69] | Singapore | 2.04 | 0.63 | 0.82 | |||

| Woodruff, 2022 [70] | United Kingdom | 2.16 | 0.61 | 0.77 | |||

| Malinauskas and Malinauskiene, 2023 [29] | Lithuania | 2.64 | 0.46 | 0.77 | |||

| Bíró et al., 2025 [47] | Hungary | 2.93 | 0.98 | 0.65 | |||

| Sport Devaluation | |||||||

| Harris and Ostrow, 2008 [56] | USA | 2.03 | 0.84 | 3.84 | 0.84 | greater p < 0.001 | 0.88 |

| Kilo and Hassmén, 2016 [67] | Australia | 1.97 | 0.73 | 0.84 | |||

| Ong and Zhao, 2018 [69] | Singapore | 1.93 | 0.69 | 0.81 | |||

| Woodruff, 2022 [70] | United Kingdom | 1.96 | 0.77 | 0.84 | |||

| Malinauskas and Malinauskiene, 2023 [29] | Lithuania | 2.08 | 0.46 | 0.71 | |||

| Bíró et al., 2025 [47] | Hungary | 2.20 | 1.18 | 0.66 | |||

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (TIE) PS → CB | −0.169 | −0.175 | 0.053 | 3.158 | 0.002 |

| Direct effect | |||||

| PS → CB | −0.382 | −0.383 | 0.075 | 5.089 | 0.000 |

| PS → MT | −0.692 | −0.699 | 0.023 | 29.711 | 0.000 |

| MT → CB | 0.244 | 0.251 | 0.077 | 3.155 | 0.002 |

| Total Effect | −0.550 | −0.558 | 0.045 | 12.224 | 0.000 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (TIE) PD→ EPE | −0.132 | −0.133 | 0.042 | 3.101 | 0.002 |

| PD → Confidence → EPE | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.025 | 1.998 | 0.046 |

| PD → Constancy → EPE | −0.122 | −0.123 | 0.046 | 2.617 | 0.009 |

| PD → Control → EPE | −0.060 | −0.061 | 0.022 | 2.730 | 0.006 |

| Direct effect | −0.369 | −0.371 | 0.064 | 5.772 | 0.000 |

| Total Effect | −0.501 | −0.505 | 0.051 | 9.891 | 0.000 |

| (TIE) PC → EPE | −0.194 | −0.199 | 0.049 | 3.926 | 0.000 |

| PC → Confidence → EPE | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.035 | 1.817 | 0.069 |

| PC → Constancy → EPE | −0.185 | −0.189 | 0.051 | 3.649 | 0.000 |

| PC → Control → EPE | −0.073 | −0.074 | 0.020 | 3.611 | 0.000 |

| Direct effect | −0.139 | −0.137 | 0.070 | 1.995 | 0.046 |

| Total Effect | −0.334 | −0.337 | 0.057 | 5.867 | 0.000 |

| (TIE) PA → EPE | −0.131 | −0.134 | 0.040 | 3.239 | 0.001 |

| PA → Confidence → EPE | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.023 | 2.137 | 0.033 |

| PA → Constancy → EPE | −0.121 | −0.123 | 0.043 | 2.837 | 0.005 |

| PA → Control → EPE | −0.058 | −0.059 | 0.018 | 3.204 | 0.001 |

| Direct effect | −0.328 | −0.327 | 0.062 | 5.249 | 0.000 |

| Total Effect | −0.458 | −0.462 | 0.050 | 9.247 | 0.000 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (TIE) PD → RSA | −0.267 | −0.273 | 0.044 | 6.023 | 0.000 |

| PD → Confidence → RSA | −0.121 | −0.123 | 0.026 | 4.609 | 0.000 |

| PD → Constancy → RSA | −0.075 | −0.078 | 0.039 | 1.900 | 0.057 |

| PD → Control → RSA | −0.071 | −0.072 | 0.025 | 2.879 | 0.004 |

| Direct effect | −0.107 | −0.103 | 0.075 | 1.424 | 0.155 |

| Total Effect | −0.373 | −0.376 | 0.056 | 6.609 | 0.000 |

| (TIE) PC → RSA | −0.317 | −0.321 | 0.046 | 6.923 | 0.000 |

| PC → Confidence → RSA | −0.154 | −0.155 | 0.033 | 4.720 | 0.000 |

| PC → Constancy → RSA | −0.100 | −0.104 | 0.042 | 2.363 | 0.018 |

| PC → Control → RSA | −0.062 | −0.063 | 0.019 | 3.211 | 0.001 |

| Direct effect | −0.055 | −0.054 | 0.070 | 0.786 | 0.432 |

| Total Effect | −0.372 | −0.375 | 0.056 | 6.692 | 0.000 |

| (TIE) PA → RSA | −0.240 | −0.245 | 0.038 | 6.321 | 0.000 |

| PA → Confidence → RSA | −0.115 | −0.117 | 0.025 | 4.578 | 0.000 |

| PA → Constancy → RSA | −0.071 | −0.074 | 0.036 | 1.961 | 0.050 |

| PA → Control → RSA | −0.053 | −0.054 | 0.018 | 2.949 | 0.003 |

| Direct effect | −0.111 | −0.109 | 0.059 | 1.866 | 0.062 |

| Total Effect | −0.350 | −0.354 | 0.051 | 6.900 | 0.000 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (TIE) PD → SD | −0.187 | −0.194 | 0.040 | 4.642 | 0.000 |

| PD → Confidence → SD | −0.064 | −0.066 | 0.029 | 2.196 | 0.028 |

| PD → Constancy → SD | −0.129 | −0.134 | 0.049 | 2.644 | 0.008 |

| PD → Control → SD | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.029 | 0.209 | 0.834 |

| Direct effect | −0.052 | −0.050 | 0.069 | 0.758 | 0.449 |

| Total Effect | −0.240 | −0.245 | 0.054 | 4.423 | 0.000 |

| (TIE) PC → SD | −0.279 | −0.288 | 0.046 | 6.140 | 0.000 |

| PC → Confidence → SD | −0.096 | −0.099 | 0.038 | 2.500 | 0.012 |

| PC → Constancy → SD | −0.178 | −0.183 | 0.053 | 3.358 | 0.001 |

| PC → Control → SD | −0.005 | −0.006 | 0.022 | 0.244 | 0.807 |

| Direct effect | 0.102 | 0.108 | 0.066 | 1.549 | 0.121 |

| Total Effect | −0.177 | −0.181 | 0.056 | 3.180 | 0.001 |

| (TIE) PA → SD | −0.163 | −0.169 | 0.037 | 4.453 | 0.000 |

| PA → Confidence → SD | −0.058 | −0.060 | 0.028 | 2.035 | 0.042 |

| PA → Constancy → SD | −0.109 | −0.113 | 0.045 | 2.430 | 0.015 |

| PA → Control → SD | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.019 | 0.208 | 0.835 |

| Direct effect | −0.104 | −0.103 | 0.065 | 1.599 | 0.110 |

| Total Effect | −0.267 | −0.272 | 0.049 | 5.471 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bíró, E.; Balogh, L. The Mediating Role of Mental Toughness in the Relationship Between Burnout and Perceived Stress Among Hungarian Coaches. Sports 2025, 13, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13060174

Bíró E, Balogh L. The Mediating Role of Mental Toughness in the Relationship Between Burnout and Perceived Stress Among Hungarian Coaches. Sports. 2025; 13(6):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13060174

Chicago/Turabian StyleBíró, Eszter, and László Balogh. 2025. "The Mediating Role of Mental Toughness in the Relationship Between Burnout and Perceived Stress Among Hungarian Coaches" Sports 13, no. 6: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13060174

APA StyleBíró, E., & Balogh, L. (2025). The Mediating Role of Mental Toughness in the Relationship Between Burnout and Perceived Stress Among Hungarian Coaches. Sports, 13(6), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13060174