Acute Decrease in Glenohumeral Internal Rotation During Repetitive Baseball Pitching Is Associated with Transient Structural Changes in Medial Longitudinal Arch of Stride Leg: Pilot Study Using Mixed Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Repetitive pitching would acutely decrease shoulder internal rotation range of motion (IRROM).

- The acute decrease in IRROM would be associated with changes in navicular height and the mechanical properties of the AbH and PF on the stride-leg side.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size Determination

2.2. Participants

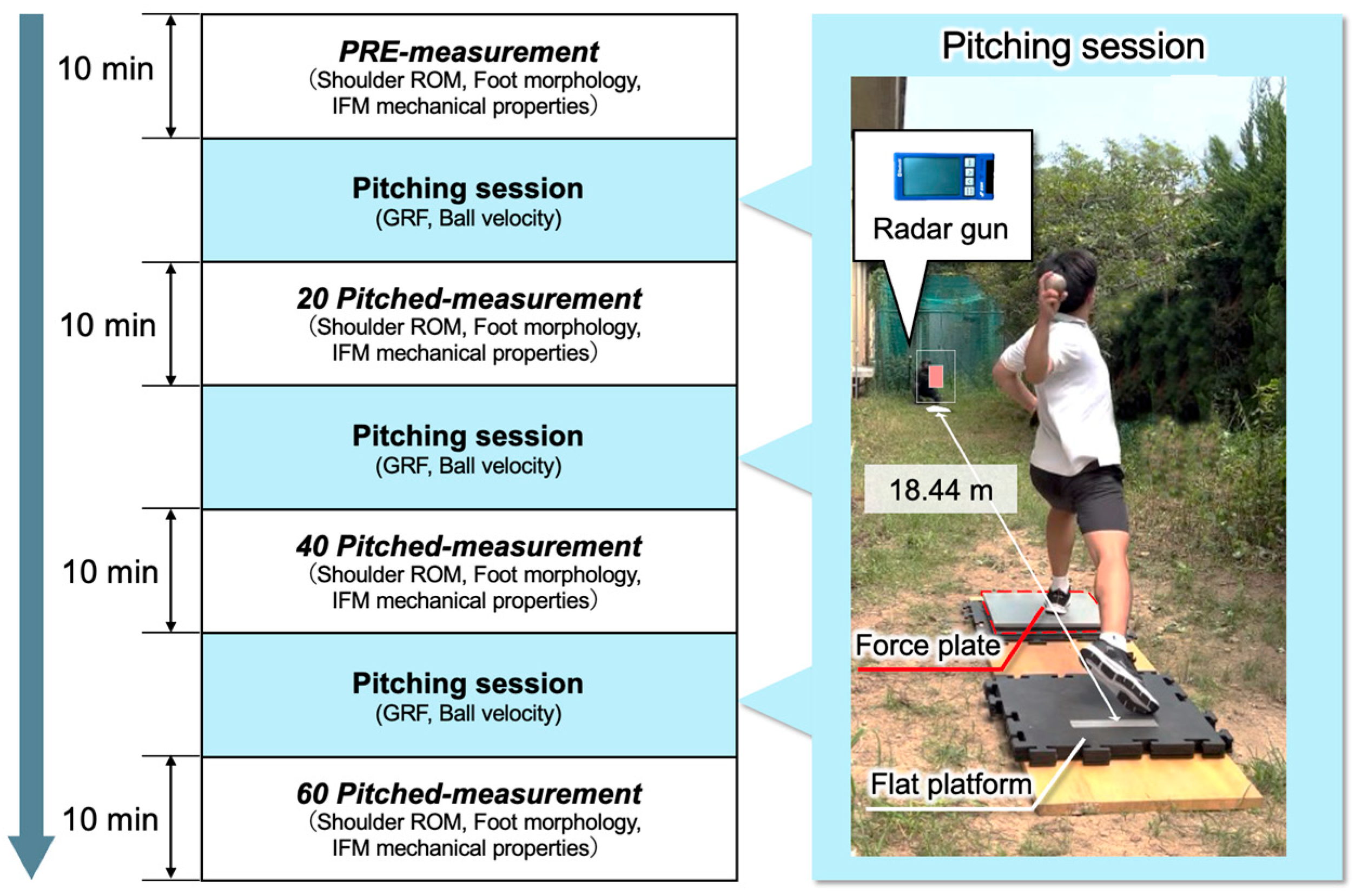

2.3. Procedures for Conducting Pitching Sessions and Measurement Sessions

2.4. Measurement of ROM of the Shoulder Joint

2.5. Morphological Assessment of the Foot

2.6. Mechanical Property Assessment of the Intrinsic Foot Muscle

2.7. Measurement of the GRF of the Stride Leg During Pitching

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

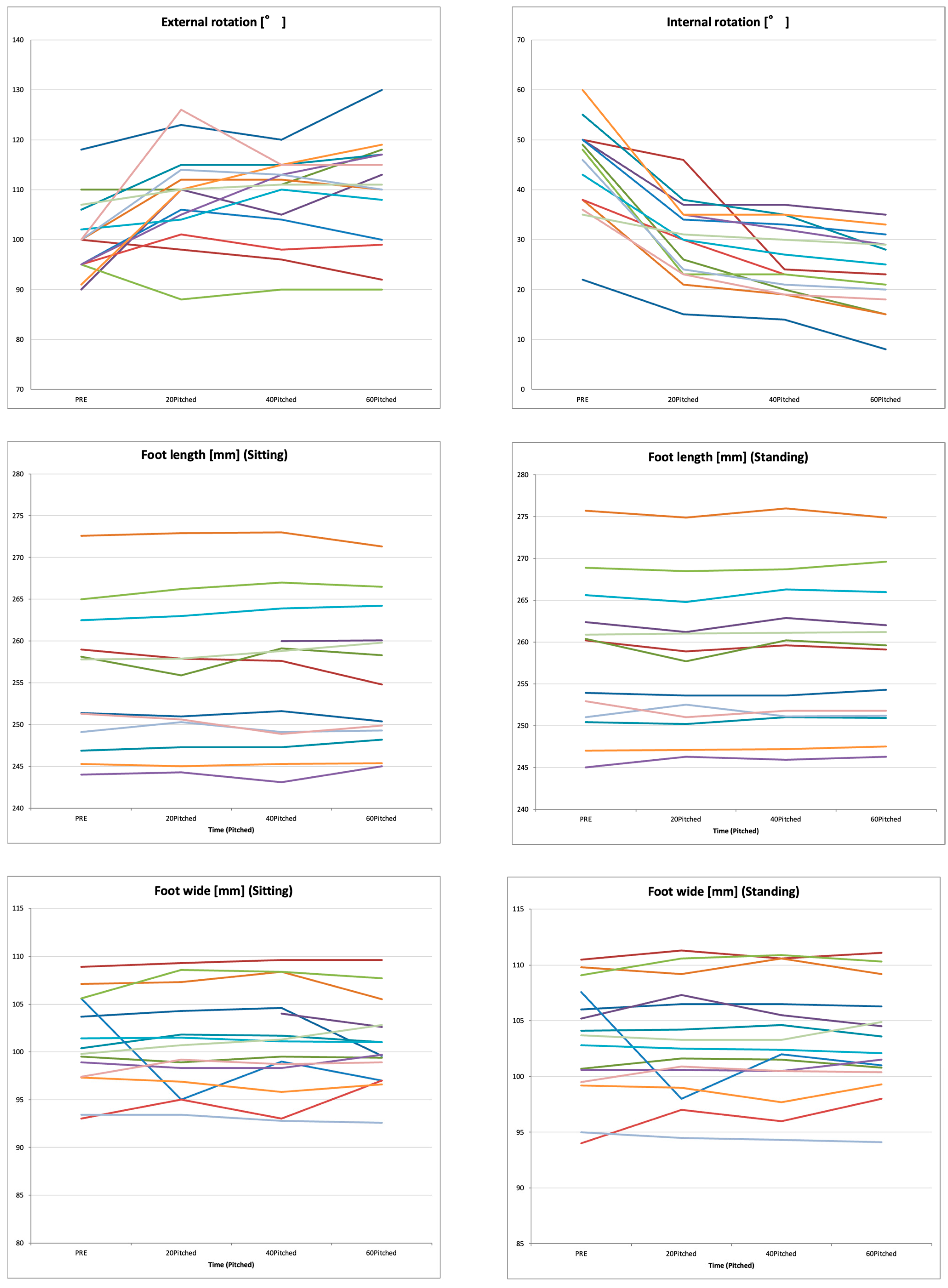

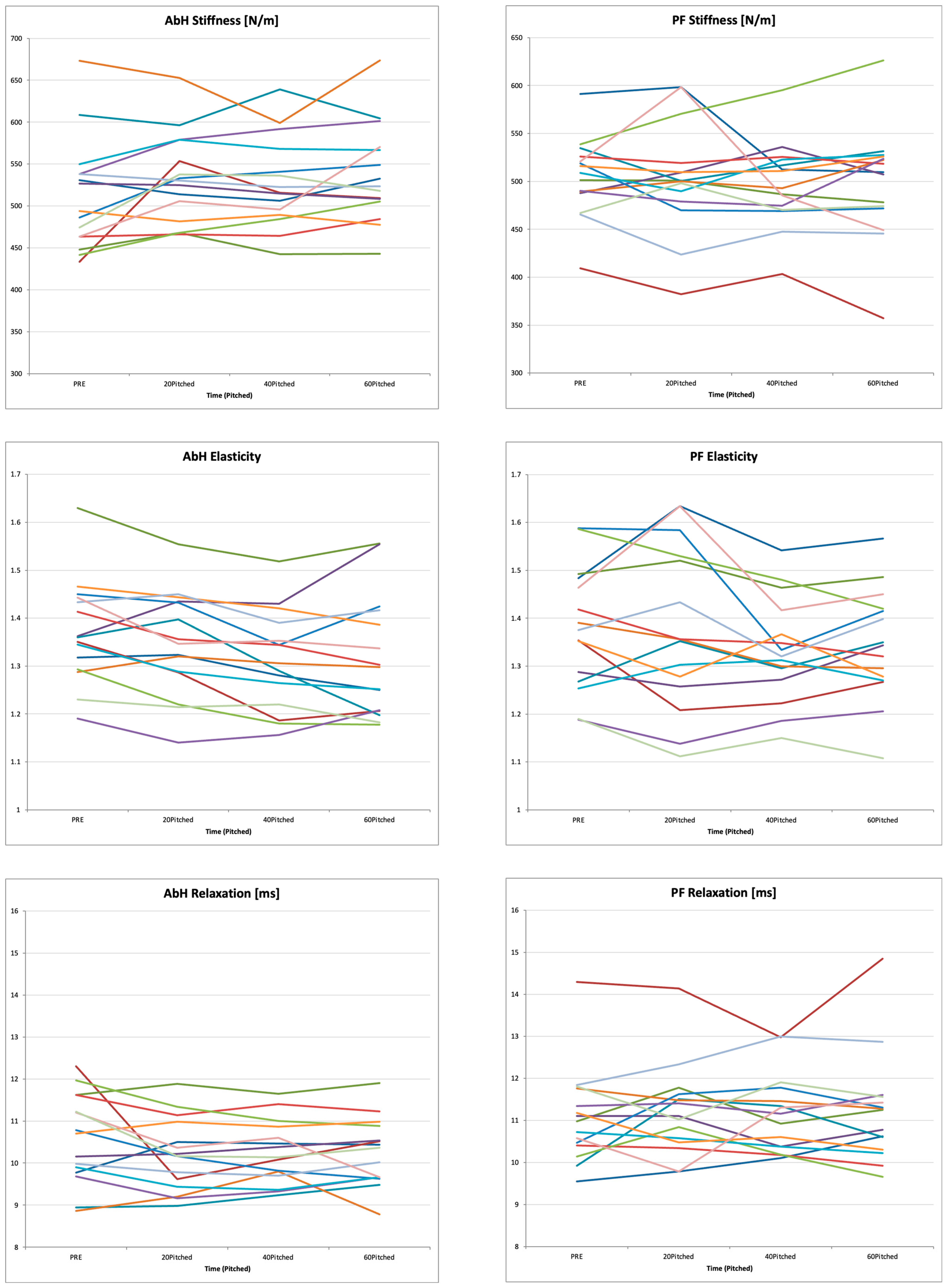

3.1. Temporal Changes in Shoulder ROM, Foot Morphology, and Muscle Mechanical Properties During Repeated Pitching

3.2. Correlations Between Changes in Shoulder IR and GRFs of the Lead Foot During Pitching

3.3. Correlations Between Changes in Shoulder IR and GRFs of the Stride Leg During Pitching

3.4. Relationship Between GRF Components and Changes in Muscle Elasticity and Pitching Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AbH | Abductor hallucis |

| BW | Body weight |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| GIRD | Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit |

| GRF | Ground reaction force |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| IR | Internal rotation |

| LHA | Leg–heel alignment |

| LMM | Linear mixed-effects model |

| MLA | Medial longitudinal arch |

| PF | Plantar fascia |

| ROM | Range of motion |

Appendix A

| Muscle | Property | ICC (1,1) | SEM | MDC95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AbH | Tone [Hz] | 0.90 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Stiffness [N/m] | 0.98 | 10.1 | 28 | |

| Elasticity | 0.92 | 0.036 | 0.099 | |

| Relaxation [ms] | 0.96 | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| Creep | 0.95 | 0.013 | 0.036 | |

| PF | Tone [Hz] | 0.88 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Stiffness [N/m] | 0.91 | 12.4 | 34.4 | |

| Elasticity | 0.96 | 0.028 | 0.078 | |

| Relaxation [ms] | 0.89 | 0.2 | 0.7 | |

| Creep | 0.94 | 0.015 | 0.041 |

| Δ Navicular Height (Sitting) [°] | Δ Navicular Height (Standing) [°] | Δ AbH Elasticity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| Δ Navicular height (sitting) [mm] | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Δ Navicular height (standing) [mm] | 0.856 ** | <0.001 | - | - | - | - |

| Δ AbH Elasticity | 0.233 | 0.073 | 0.274 * | 0.034 | - | - |

References

- Burkhart, S.S.; Morgan, C.D.; Kibler, W.B. The disabled throwing shoulder: Spectrum of pathology part I: Patho-anatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy 2003, 19, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.B.; Noonan, T. Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit in throwing athletes: Current perspectives. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2018, 9, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.A.; De Giacomo, A.F.; Neumann, J.A.; Limpisvasti, O.; Tibone, J.E. Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit and risk of upper extremity injury in overhead athletes: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Sports Health 2018, 10, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.H.; Huang, T.S.; Huang, C.Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Tsai, Y.S.; Lin, J.J. Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit on pitching biomechanics and muscle activity. Int. J. Sports Med. 2022, 43, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.W.; Sheridan, S.; Reuther, K.E.; Kelly, J.D., IV; Thomas, S.J. The contribution of posterior capsule hypertrophy to soft tissue glenohumeral internal rotation deficit in healthy pitchers. Am. J. Sports Med. 2022, 50, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirabito, N.S.; Topley, M.; Thomas, S.J. Acute effect of pitching on range of motion, strength, and muscle architecture. Am. J. Sports Med. 2022, 50, 1382–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaga, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Goto, H.; Nozaki, M.; Fukuyoshi, M.; Tsuchiya, A.; Murase, A.; Ono, T.; Otsuka, T. Posterior shoulder capsules are thicker and stiffer in the throwing shoulders of healthy college baseball players: A quantitative assessment using shear-wave ultrasound elastography. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 2935–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, W.B. Clinical biomechanics of the elbow in tennis: Implications for evaluation and diagnosis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 1203–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinaldo, A.L.; Buttermore, J.; Chambers, H. Effects of upper trunk rotation on shoulder joint torque among baseball pitchers of various levels. J. Appl. Biomech. 2007, 23, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, M.; Sugiyama, T.; Takai, Y.; Kanehisa, H.; Maeda, A. Kinematic and kinetic profiles of trunk and lower limbs during baseball pitching in collegiate pitchers. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2014, 13, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aguinaldo, A.L.; Chambers, H. Correlation of throwing mechanics with elbow valgus load in adult baseball pitchers. Am. J. Sports Med. 2009, 37, 2043–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciascia, A.; Thigpen, C.; Namdari, S.; Baldwin, K. Kinetic chain abnormalities in the athletic shoulder. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2012, 20, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, J.A., Jr.; Werner, S.L. Lower-extremity ground reaction forces in collegiate baseball pitchers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 1782–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, Y.; Oi, T.; Tanaka, H.; Inui, H.; Fujioka, H.; Tanaka, J.; Yoshiya, S.; Nobuhara, K. Increased horizontal shoulder abduction is associated with an increase in shoulder joint load in baseball pitching. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014, 23, 1757–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, M.P.; Borstad, J.D.; Oñate, J.A.; Chaudhari, A.M. Stride leg ground reaction forces predict throwing velocity in adult recreational baseball pitchers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2708–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howenstein, J.; Kipp, K.; Sabick, M.B.; Brophy, R.H. Peak horizontal ground reaction forces and impulse correlate with energy flow from the trunk to the arm in baseball pitching. J. Appl. Biomech. 2020, 36, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakase, K.; Shitara, H.; Tajika, T.; Kuboi, T.; Ichinose, T.; Sasaki, T.; Hamano, N.; Endo, F.; Kamiyama, M.; Miyamoto, R.; et al. The Relationship Between Dynamic Balance Ability and Shoulder Pain in High School Baseball Pitchers. Sports Health 2022, 14, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigenbaum, L.A.; Roach, K.E.; Kaplan, L.D.; Lesniak, B.; Cunningham, S. The association of foot arch posture and prior history of shoulder or elbow surgery in elite-level baseball pitchers. J. Orthop Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 43, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiolkowski, P.; Brunt, D.; Bishop, M.; Woo, R.; Horodyski, M. Intrinsic pedal musculature support of the medial longitudinal arch: An electromyography study. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2003, 42, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, N.; Hirota, A.; Komiya, M.; Morikawa, M.; Mizuta, R.; Fujishita, H.; Nishikawa, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Urabe, Y. Intrinsic foot muscle hardness is related to dynamic postural stability after landing in healthy young men. Gait Posture 2021, 86, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Swart, A.F.M.J.; van Trigt, B.; Wasserberger, K.; Hoozemans, M.J.M.; Veeger, D.H.E.J.; Oliver, G.D. Energy flow through the lower extremities in high school baseball pitching. Sports Biomech. 2022, 22, 1081–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takabayashi, T.; Edama, M.; Inai, T.; Kubo, M. Differences in rearfoot, midfoot, and forefoot kinematics of normal foot and flatfoot during running. J. Orthop. Res. 2021, 39, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, S.; Maeda, N.; Komiya, M.; Tashiro, T.; Yoshimi, M.; Mizuta, R.; Ishida, A.; Urabe, Y. Acute effects of running 10 km on the medial longitudinal arch height: Dynamic evaluation using a three-dimensional motion capture system during gait. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 2024, 52, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiotani, H.; Mizokuchi, T.; Yamashita, R.; Naito, M.; Kawakami, Y. Acute effects of long-distance running on mechanical and morphological properties of the human plantar fascia. Scand J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Hirota, K.; Otsuki, R.; Onodera, J.; Kodesho, T.; Taniguchi, K. Morphological and mechanical characteristics of the intrinsic and extrinsic foot muscles under loading in individuals with flat feet. Gait Posture 2024, 108, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mits, S.; Coorevits, P.; De Clercq, D.; Elewaut, D.; Woodburn, J.; Roosen, P. Reliability and validity of the INFOOT three-dimensional foot digitizer for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2011, 101, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Lin, G.; Wang, M.J. Comparing 3D foot scanning with conventional measurement methods. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2014, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, A.; Piérola, A.; Parrilla, E.; Izquierdo, M.; Uriel, J.; Nácher, B.; Ortiz, V.; González, J.C.; Page, Á.F.; Alemany, S. Fast, portable and low-cost 3D foot digitizers: Validity and reliability of measurements. In Proceedings of the 3DBODY.TECH 2017 8th International Conference and Exhibition on 3D Body Scanning and Processing Technologies, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–12 October 2017; pp. 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maeda, N.; Ikuta, Y.; Tsutsumi, S.; Arima, S.; Ishihara, H.; Ushio, K.; Mikami, Y.; Komiya, M.; Nishikawa, Y.; Nakasa, T.; et al. Relationship of chronic ankle instability with foot alignment and dynamic postural stability in adolescent competitive athletes. Orthop J. Sports Med. 2023, 11, 23259671231202220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viir, R.; Laiho, K.; Kramarenko, J.; Mikkelsson, M. Repeatability of trapezius muscle tone assessment by a myometric method. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2006, 6, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orner, S.; Kratzer, W.; Schmidberger, J.; Grüner, B. Quantitative tissue parameters of Achilles tendon and plantar fascia in healthy subjects using a handheld myotonometer. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2018, 22, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinci Incel, N.; Genç, H.; Erdem, H.R.; Yorgancioglu, Z.R. Muscle imbalance in hallux valgus: An electromyographic study. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003, 82, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltner, M.E.; Dapena, J. Dynamics of the shoulder and elbow joints of the throwing arm during a baseball pitch. Int. J. Sport Biomech. 1986, 2, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G. Effect size guidelines for individual and group differences in physiotherapy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 106, 1844–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber-Gregory, D.N. Ridge regression and multicollinearity: An in-depth review. Model Assist. Stat. Appl. 2018, 13, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freehill, M.T.; Archer, K.R.; Diffenderfer, B.W.; Ebel, B.G.; Cosgarea, A.J.; McFarland, E.G. Changes in collegiate starting pitchers’ range of motion after single game and season. Phys. Sportsmed. 2014, 42, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinold, M.M.; Wilk, K.E.; Macrina, L.C.; Sheheane, C.; Dun, S.; Fleisig, G.S.; Crenshaw, K.; Andrews, J.R. Changes in shoulder and elbow passive range of motion after pitching in professional baseball players. Am. J. Sports Med. 2008, 36, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, M.G.; Tibone, J.E.; McGarry, M.H.; Schneider, D.J.; Veneziani, S.; Lee, T.Q. A cadaveric model of the throwing shoulder: A possible etiology of superior labrum anterior-to-posterior lesions. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2005, 87, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opplert, J.; Babault, N. Acute effects of dynamic stretching on muscle flexibility and performance: An analysis of the current literature. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Watanabe, D.; Wada, M. Eccentric muscle contraction potentiates titin stiffness-related contractile properties in rat fast-twitch muscles. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2022, 133, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, A.L.; Lindstedt, S.L.; Nishikawa, K.C. Physiological mechanisms of eccentric contraction and its applications: A role for the giant titin protein. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridén, J.; Sfakianos, P.N.; Hargens, A.R. Muscle soreness and intramuscular fluid pressure: Comparison between eccentric and concentric load. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 1986, 61, 2175–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Johnson, M.; Bader, D.A.; Cortes, D.H. The shear modulus of lower-leg muscles correlates to intramuscular pressure. J. Biomech. 2019, 83, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawama, R.; Yamamoto, M.; Matsuo, S.; Shinohara, M. Factors influencing acute and chronic changes in muscle stiffness: A narrative review. J. Phys. Fit Sports Med. 2024, 13, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Bíró, I.; Sárosi, J.; Fang, Y.; Gu, Y. Comparison of ground reaction forces as running speed increases between male and female runners. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1378284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.L.-W.; Agresta, C.E.; Lipps, D.B.; Provenzano, S.G.; Hafer, J.F.; Wong, D.W.-C.; Zhang, M.; Zernicke, R.F. Ultrasound elastographic assessment of plantar fascia in runners using rearfoot strike and forefoot strike. J. Biomech. 2019, 89, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumpl, L.; Schiele, N.R.; Cannavan, D.; Larkins, L.W.; Brown, A.F.; Bailey, J.P. Acute effects of high-intensity interval running on plantar fascia thickness and stiffness in healthy adults. J. Appl. Biomech. 2025, 41, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.; Martin, R.; Welch, H.; Williams, L.; Morris, K. Objective assessment of stiffness in the gastrocnemius muscle in patients with symptomatic Achilles tendons. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2019, 5, e000622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, K.; Egawa, K.; Ikeda, T.; Fukuda, K.; Kanai, S. Relationship between foot muscle morphology and severity of pronated foot deformity and foot kinematics during gait: A preliminary study. Gait Posture 2021, 86, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, K.F.; Hulburt, T.C.; Kimura, B.M.; Aguinaldo, A.L. Relationship between ground reaction force and throwing arm kinetics in high school and collegiate pitchers. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2022, 62, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagamoto, H.; Takahashi, S.; Okunuki, T.; Wakamiya, K.; Maemichi, T.; Kurokawa, D.; Muraki, T.; Takahashi, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Aizawa, T.; et al. Prevalence of impaired foot function in baseball players with and without disabled throwing shoulder/elbow: A case–control study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, X.; Yu, P.; Song, Y.; Sun, D.; Liang, M.; Bíró, I.; Gu, Y. Influence of medial longitudinal arch flexibility on lower limb joint coupling coordination and gait impulse. Gait Posture 2024, 114, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserberger, K.W.; Giordano, K.A. Ground reaction forces in baseball pitching: Temporal associations with pitch velocity among high-velocity pitchers. Sports Biomech. 2023, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, A.C.; Crosbie, J.; Ouvrier, R.A. Development and validation of a novel rating system for scoring foot posture: The Foot Posture Index. Clin. Biomech. 2006, 21, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClymont, J.; Forsyth, A. Reliability of the arch height index measurement system and Foot Posture Index in adults: A systematic review. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2020, 36, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | PRE | 20 Pitched | 40 Pitched | 60 Pitched | F | p | η2G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Shoulder ROM in 90°-Abducted | |||||||

| External rotation [°] | 100.3 ± 7.5 | 108.8 ± 9.4 * | 108.5 ± 8.31 ** | 109.9 ± 10.8 * | 11.048 | <0.001 | 0.162 |

| Internal rotation [°] | 45.3 ± 10.2 | 29.9 ± 8.0 * | 26.1 ± 7.12 ** | 23.4 ± 7.6 **,††,§§ | 76.262 | <0.001 | 0.528 |

| 2. Foot morphological parameter | |||||||

| Foot length [mm] (Sitting) | 255.3 ± 8.1 | 255.2 ± 8.8 | 255.7 ± 9.0 | 255.6 ± 8.4 | 0.090 | 0.965 | 0.074 × 10−3 |

| Foot length [mm] (Standing) | 257.9 ± 8.6 | 257.5 ± 8.5 | 258.1 ± 9.0 | 258.0 ± 8.7 | 0.085 | 0.956 | 0.078 × 10−2 |

| Foot wide [mm] (Sitting) | 101.0 ± 4.7 | 100.7 ± 5.1 | 101.1 ± 5.2 | 100.7 ± 4.4 | 0.079 | 0.903 | 0.052 × 10−2 |

| Foot wide [mm] (Standing) | 103.2 ± 5.1 | 103.1 ± 5.1 | 103.1 ± 5.1 | 103.1 ± 4.7 | 0.012 | 0.998 | 0.042 × 10−3 |

| Navicular height [mm] (Sitting) | 44.3 ± 3.7 | 42.8 ± 3.8 | 41.7 ± 4.6 * | 40.0 ± 3.8 **,†† | 13.715 | <0.001 | 0.141 |

| Navicular height [mm] (Standing) | 39.7 ± 4.6 | 38.1 ± 4.5 * | 36.4 ± 4.6 ** | 35.1 ± 4.5 **,†† | 19.836 | <0.001 | 0.138 |

| LHA [°] | 6.1 ± 3.5 | 6.1 ± 3.2 | 6.3 ± 3.3 | 6.5 ± 3.6 | 0.364 | 0.707 | 0.002 |

| 3. Mechanical properties of muscle | |||||||

| 3-1. Abductor Hallucis | |||||||

| Tone [Hz] | 23.4 ± 1.8 | 24.1 ± 1.4 | 24.0 ± 1.3 | 24.1 ± 1.5 | 3.137 | 0.067 | 0.043 |

| Stiffness [N/m] | 511.2 ± 66.0 | 532.7 ± 53.3 | 527.5 ± 53.4 | 537.8 ± 58.5 * | 3.450 | 0.025 | 0.031 |

| Elasticity | 1.37 ± 0.11 | 1.35 ± 0.11 | 1.31 ± 0.10 **,† | 1.32 ± 0.13 * | 6.218 | 0.007 | 0.048 |

| Relaxation Time [ms] | 10.6 ± 1.1 | 10.2 ± 0.9 | 10.3 ± 0.7 | 10.2 ± 0.8 | 2.364 | 0.123 | 0.023 |

| Creep | 0.70 ± 0.10 | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 0.611 | 0.574 | 0.014 |

| 3-2. Planter Fascia | |||||||

| Tone [Hz] | 23.2 ± 1.3 | 23.2 ± 1.7 | 23.3 ± 1.21 | 23.3 ± 1.8 | 0.053 | 0.984 | 0.001 |

| Stiffness [N/m] | 504.4 ± 40.9 | 503.3 ± 57.3 | 496.6 ± 43.9 | 497.9 ± 58.4 | 0.281 | 0.740 | 0.005 |

| Elasticity | 1.40 ± 0.10 | 1.38 ± 0.17 | 1.33 ± 0.11 | 1.34 ± 0.12 | 2.567 | 0.067 | 0.025 |

| Relaxation Time [ms] | 11.1 ± 1.1 | 11.2 ± 1.1 | 11.2 ± 0.9 | 11.2 ± 1.3 | 0.272 | 0.845 | 0.003 |

| Creep | 0.74 ± 0.10 | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 0.75 ± 0.08 | 0.74 ± 0.07 | 0.321 | 0.746 | 0.006 |

| 4. Pitching performance | |||||||

| Ball velocity [km/h] | 100.9 ± 5.3 | 101.7 ± 4.8 | 100.8 ± 5.4 | 0.475 | 0.627 | 0.006 | |

| Fastball velocity [km/h] | 109.0 ± 6.0 | 109.6 ± 5.0 | 109.2 ± 6.2 | 0.243 | 0.742 | 0.002 | |

| 5. Pitching kinetics parameter | |||||||

| Peak_GRF_Anteroposterior component [%BW] | 18.0 ± 4.1 | 17.5 ± 4.9 | 18.7 ± 4.4 | 0.742 | 0.476 | 0.013 | |

| Peak_GRF_Mediolateral component [%BW] | 72.7 ± 10.8 | 73.3 ± 7.7 | 77.5 ± 11.6 | 2.926 | 0.082 | 0.045 | |

| Peak_GRF_Vertical component [%BW] | 175.0 ± 10.9 | 184.9 ± 25.4 | 182.5 ± 25.1 | 1.662 | 0.210 | 0.039 |

| ΔIRROM [°] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | 95% CI | |

| Δ Navicular height (sitting) [mm] | 0.520 ** | <0.001 | [0.27, 0.71] |

| Δ Navicular height (standing) [mm] | 0.596 ** | <0.001 | [0.38, 0.76] |

| Δ Leg heel angle [°] | 0.141 | 0.299 | [−0.17, 0.42] |

| Δ AbH Tone [Hz] | −0.118 | 0.368 | [−0.40, 0.19] |

| Δ AbH Stiffness [N/m] | −0.151 | 0.250 | [−0.43, 0.16] |

| Δ AbH Elasticity | 0.427 ** | <0.001 | [0.13, 0.65] |

| Δ AbH Relaxation [ms] | 0.083 | 0.527 | [−0.23, 0.38] |

| Δ AbH Creep | −0.053 | 0.689 | [−0.35, 0.26] |

| Δ PF Tone [Hz] | −0.049 | 0.713 | [−0.34, 0.27] |

| Δ PF Stiffness [N/m] | 0.015 | 0.908 | [−0.28, 0.31] |

| Δ PF Elasticity | 0.181 | 0.167 | [−0.13, 0.46] |

| Δ PF Relaxation [ms] | −0.117 | 0.374 | [−0.40, 0.19] |

| Δ PF Creep | −0.146 | 0.267 | [−0.43, 0.16] |

| Fastball velocity [km/h] | 0.013 | 0.933 | [−0.28, 0.30] |

| Peak_GRF_Anteroposterior component [%BW] | 0.189 | 0.213 | [−0.12, 0.47] |

| Peak_GRF_Mediolateral component [%BW] | 0.234 | 0.122 | [−0.08, 0.50] |

| Peak_GRF_Vertical component [%BW] | −0.380 * | 0.010 | [−0.61, −0.10] |

| R2 | Fixed Effect | Estimate (β) | SE | Df | t-Value | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.596 | Intercept | −2.303 | 7.653 | 35.109 | −0.301 | 0.765 | [−17.838, 13.233] |

| Time = 20 Pitched | 3.494 | 1.920 | 34.278 | 1.820 | 0.077 | [−0.406, 7.395] | |

| Time = 40 Pitched | 2.426 | 1.067 | 26.707 | 2.274 | 0.031 * | [0.236, 4.616] | |

| Time = 60 Pitched | Reference | - | - | - | - | - | |

| ΔStand_Navicular_Height | 0.465 | 0.350 | 35.945 | 1.330 | 0.192 | [−0.244, 1.174] | |

| ΔAbH_Elasticity | 29.235 | 14.164 | 38.095 | 2.064 | 0.046 * | [0.978, 55.257] | |

| Peak_GRF_Vertical_component | −0.087 | 0.036 | 30.666 | −2.424 | 0.021 * | [−0.160, −0.014] |

| Fixed Effect | Estimate (β) | SE | Df | t-Value | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔAbH_Elasticity | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.094 | 0.094 | 43.626 | 0.993 | 0.326 | [−0.096, 0.283] |

| Peak_GRF_Anteroposterior component | −0.003 | 0.003 | 44.917 | −1.240 | 0.221 | [−0.008, 0.002] |

| Peak_GRF_Mediolateral component | 0.001 | 0.001 | 43.699 | 1.007 | 0.320 | [−0.001, 0.002] |

| Peak_GRF_Vertical component | −0.001 | 0 | 43.258 | −2.050 | 0.047 * | [−0.002, −0.0001] |

| Fastball velocity [km/h] | ||||||

| Intercept | 99.878 | 6.036 | 32.118 | 16.546 | <0.001 | [87.584, 112.172] |

| Peak_GRF_Anteroposterior component | 0.363 | 0.167 | 31.795 | 2.170 | 0.038 * | [0.022, 0.703] |

| Peak_GRF_Mediolateral component | −0.043 | 0.051 | 33.479 | −0.839 | 0.407 | [−0.148, 0.061] |

| Peak_GRF_Vertical component | 0.032 | 0.028 | 29.837 | 1.148 | 0.260 | [−0.025, 0.088] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abekura, T.; Maeda, N.; Tashiro, T.; Arima, S.; Kaizuka, R.; Koyanagi, M.; Iwata, K.; Yoshida, H.; Ito, G.; Ueda, M.; et al. Acute Decrease in Glenohumeral Internal Rotation During Repetitive Baseball Pitching Is Associated with Transient Structural Changes in Medial Longitudinal Arch of Stride Leg: Pilot Study Using Mixed Model. Sports 2025, 13, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120446

Abekura T, Maeda N, Tashiro T, Arima S, Kaizuka R, Koyanagi M, Iwata K, Yoshida H, Ito G, Ueda M, et al. Acute Decrease in Glenohumeral Internal Rotation During Repetitive Baseball Pitching Is Associated with Transient Structural Changes in Medial Longitudinal Arch of Stride Leg: Pilot Study Using Mixed Model. Sports. 2025; 13(12):446. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120446

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbekura, Takeru, Noriaki Maeda, Tsubasa Tashiro, Satoshi Arima, Ryosuke Kaizuka, Madoka Koyanagi, Koshi Iwata, Haruka Yoshida, Ginji Ito, Mayu Ueda, and et al. 2025. "Acute Decrease in Glenohumeral Internal Rotation During Repetitive Baseball Pitching Is Associated with Transient Structural Changes in Medial Longitudinal Arch of Stride Leg: Pilot Study Using Mixed Model" Sports 13, no. 12: 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120446

APA StyleAbekura, T., Maeda, N., Tashiro, T., Arima, S., Kaizuka, R., Koyanagi, M., Iwata, K., Yoshida, H., Ito, G., Ueda, M., & Yamada, T. (2025). Acute Decrease in Glenohumeral Internal Rotation During Repetitive Baseball Pitching Is Associated with Transient Structural Changes in Medial Longitudinal Arch of Stride Leg: Pilot Study Using Mixed Model. Sports, 13(12), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120446