High-Intensity Functional Training: Perceived Functional and Psychosocial Health-Related Outcomes from Current Participants with Mobility-Related Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. High-Intensity Functional Training (HIFT)

1.2. Study Purpose

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Approach

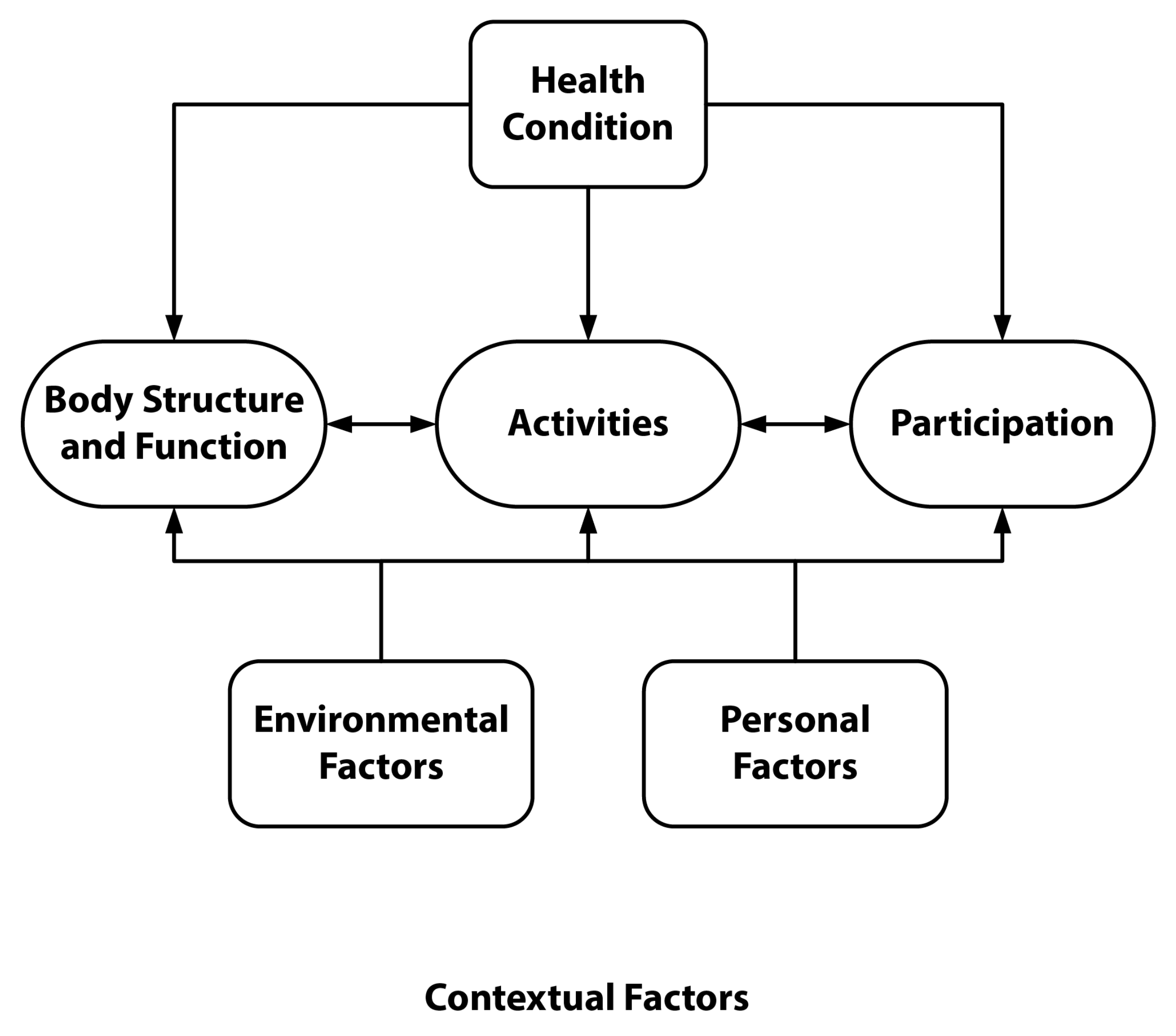

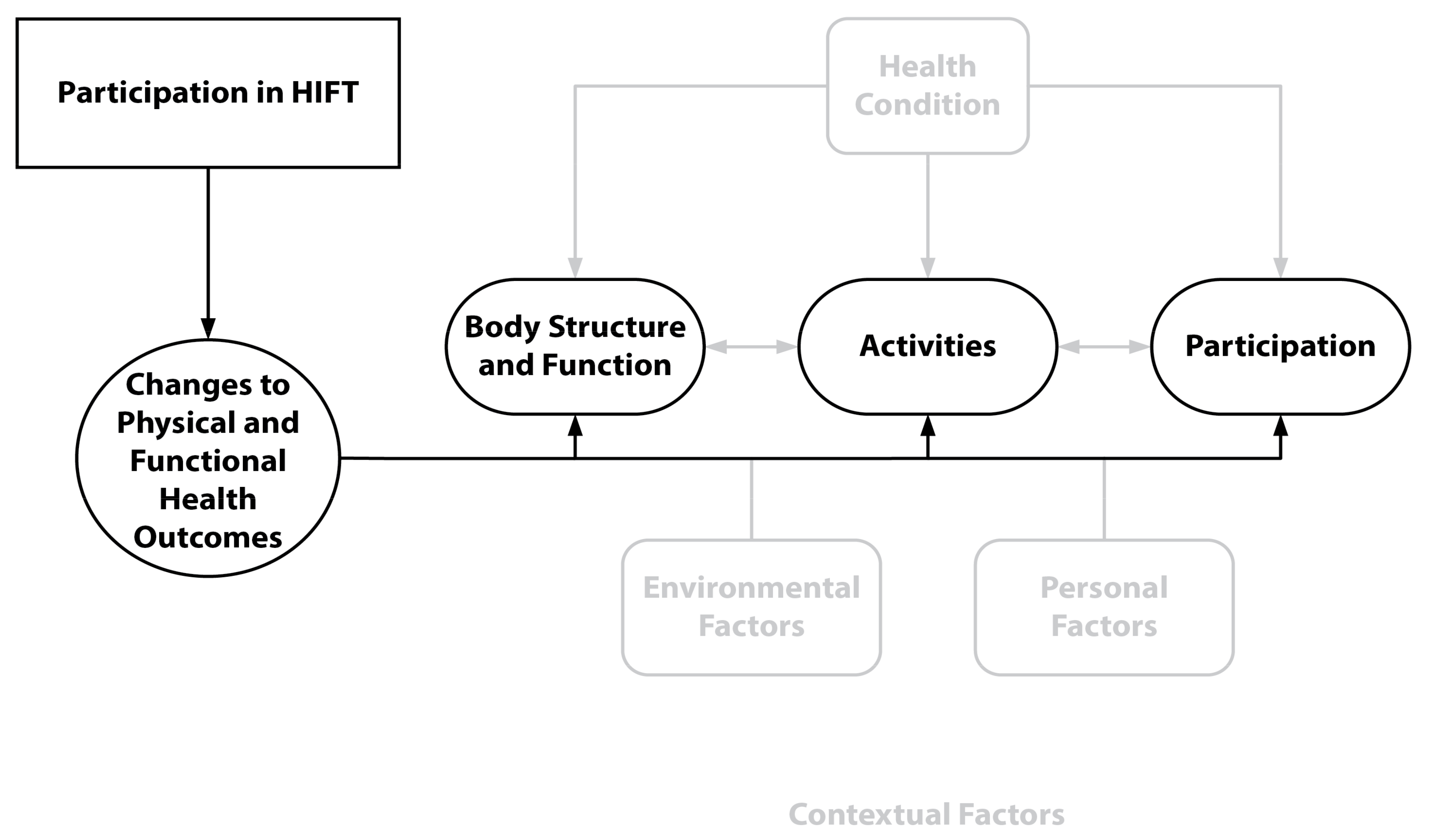

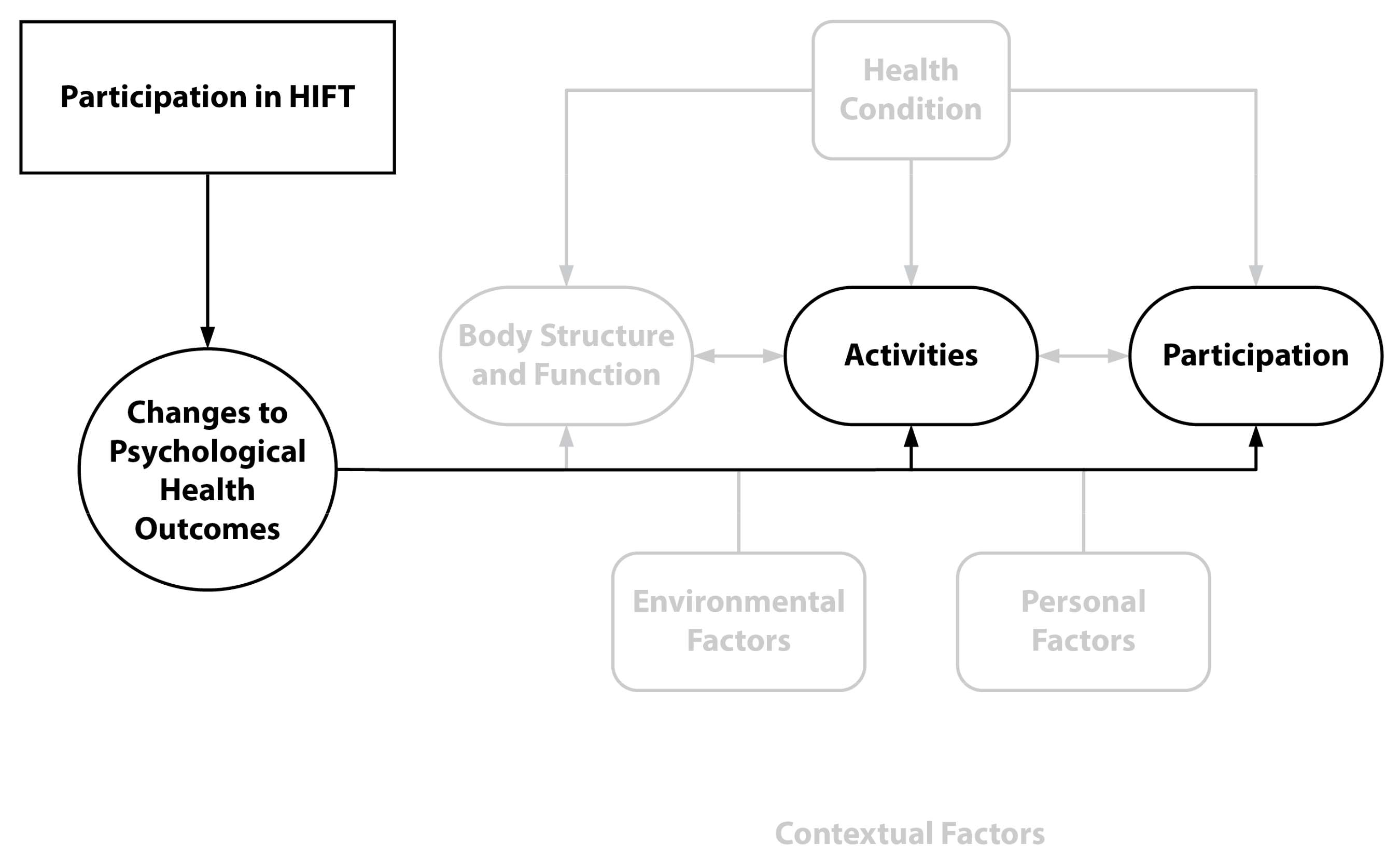

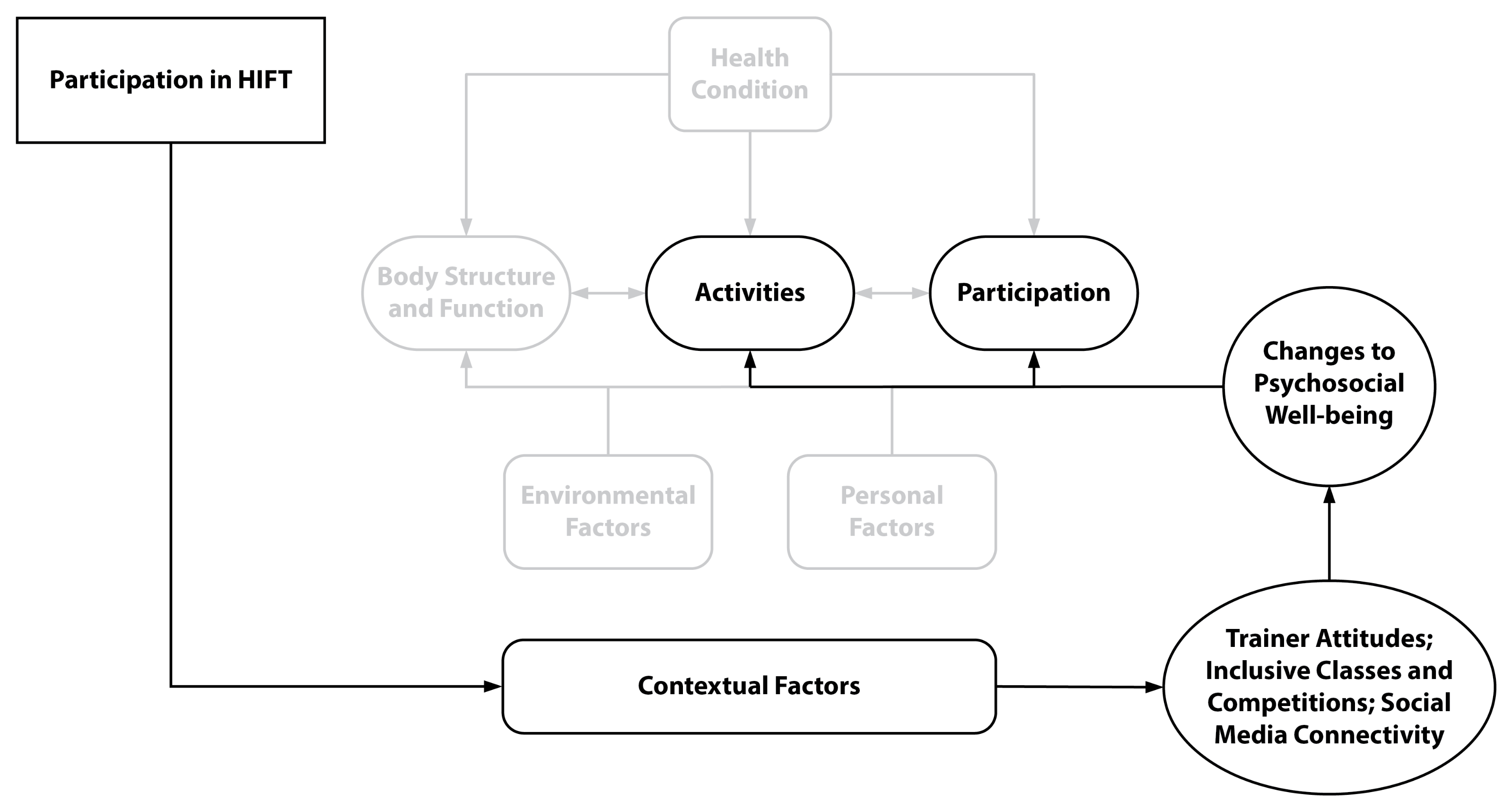

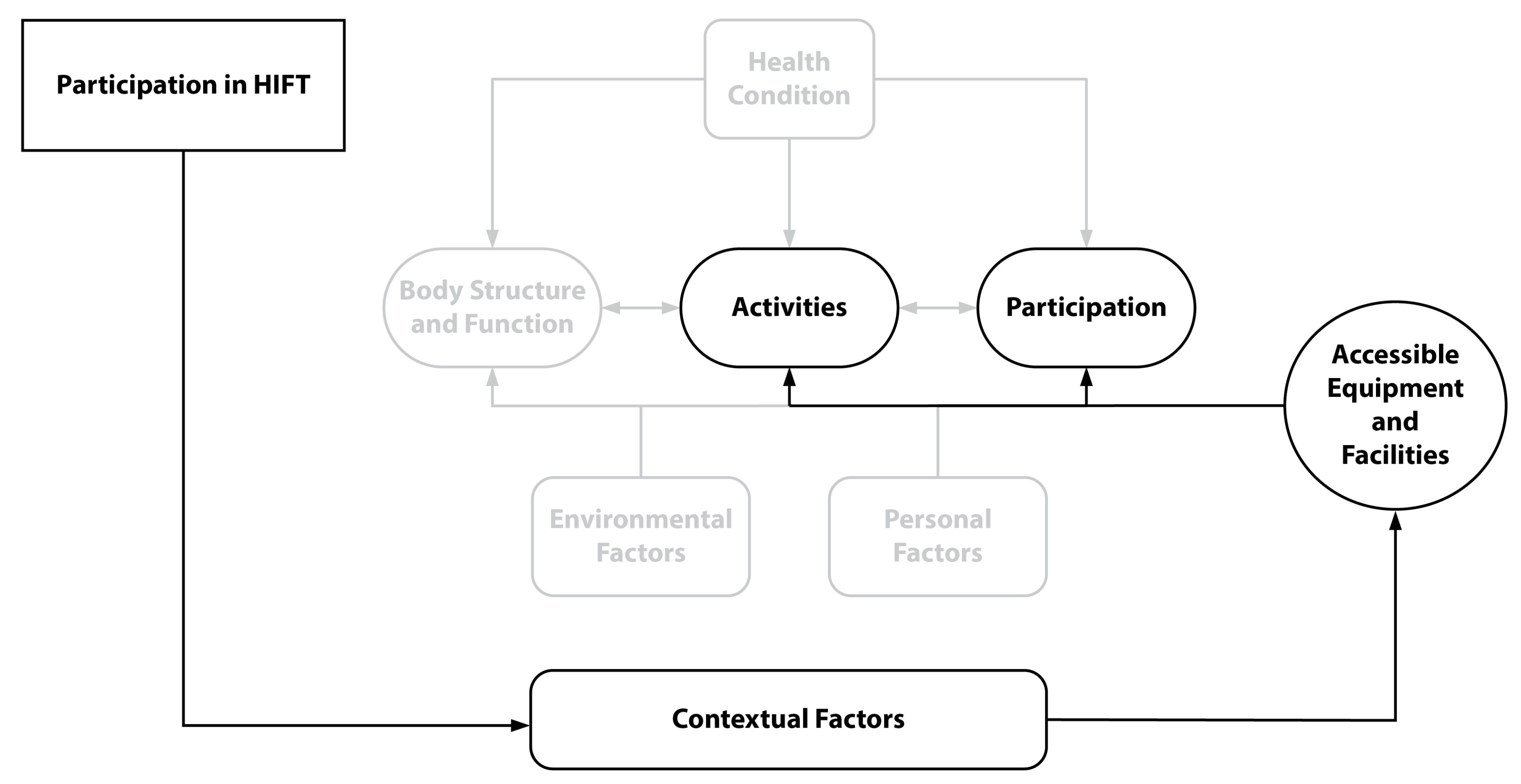

2.2. Conceptual Framework

2.3. Participant Recruitment, Criteria, and Sampling

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Participants

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.3. Health Themes

3.3.1. Physical and Functional Health Outcomes

3.3.2. Psychological Health Outcomes

3.3.3. Psychosocial Well-Being Themes

3.4. Contextual Factor Themes

3.4.1. The HIFT Environment

3.4.2. Advice for Others

4. Discussion and Implications

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lai, B.; Young, H.-J.; Bickel, C.S.; Motl, R.W.; Rimmer, J.H. Current trends in exercise intervention research, technology, and behavioral change strategies for people with disabilities: A scoping review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 96, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, J.; Lai, B. Framing new pathways in transformative exercise for individuals with existing and newly acquired disability. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.L.; Ma, J.K.; Martin Ginis, K.A. Participant experiences and perceptions of physical activity-enhancing interventions for people with physical impairments and mobility limitations: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research evidence. Health Psychol. Rev. 2017, 11, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazipour, C.H.; Evans, M.B.; Leo, J.; Lithopoulos, A.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Program conditions that foster quality physical activity participation experiences for people with a physical disability: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehn, M.; Kroll, T. Staying physically active after spinal cord injury: A qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators to exercise participation. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Riley, B.; Wang, E.; Rauworth, A.; Jurkowski, J. Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities: Barriers and facilitators. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 26, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, L.A.; Barfield, J.P.; Brasher, J.D. Perceived benefits and barriers to exercise among persons with physical disabilities or chronic health conditions within action or maintenance stages of exercise. Disabil. Health J. 2012, 5, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scelza, W.M.; Kalpakjian, C.Z.; Zemper, E.D.; Tate, D.G. Perceived barriers to exercise in people with spinal cord injury. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 84, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayes, N.M.; McPherson, K.M.; Taylor, D.; Schlüter, P.J.; Kolt, G.S. Facilitators and barriers to engagement in physical activity for people with multiple sclerosis: A qualitative investigation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.L.; Smith, B.; Papathomas, A. The barriers, benefits and facilitators of leisure time physical activity among people with spinal cord injury: A meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 404–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarsma, E.A.; Dijkstra, P.U. Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2014, 24, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, K.; Morris, E.A.; Kwon, J. Disability, access to out-of-home activities, and subjective well-being. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 163, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letts, L.; Ginis, K.A.M.; Faulkner, G.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Gorczynski, P. Preferred methods and messengers for delivering physical activity information to people with spinal cord injury: A focus group study. Rehabil. Psychol. 2011, 56, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levins, S.M.; Redenbach, D.M.; Dyck, I. Individual and societal influences on participation in physical activity following spinal cord injury: A qualitative study. Phys. Ther. 2004, 84, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, G.; Brorsson, A.; Hansson, E.E.; Troein, M.; Strandberg, E.L. Physical activity on prescription (PAP) from the general practitioner’s perspective–a qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, S.; Malone, E.; Lekiachvili, A.; Briss, P. Health care industry insights: Why the use of preventive services is still low. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Kim, Y.; Wilroy, J.; Bickel, C.S.; Rimmer, J.H.; Motl, R.W. Sustainability of exercise intervention outcomes among people with disabilities: A secondary review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1584–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hak, P.T.; Hodzovic, E.; Hickey, B. The nature and prevalence of injury during CrossFit training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kercher, V.M.; Kercher, K.; Bennion, T.; Levy, P.; Alexander, C.; Amaral, P.C.; Li, Y.-M.; Han, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R. 2022 Fitness Trends from around the Globe. ACSM’s Health Fit. J. 2022, 26, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official CrossFit Affiliate Map. 2022. Available online: https://map.crossfit.com/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Henderson, S. CrossFit’s Explosive Affiliate Growth by the Numbers. In Morning Chalk Up. 2018. Available online: https://morningchalkup.com/2018/10/23/crossfits-explosive-affilaite-growth-by-the-numbers/ (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Heinrich, K.M.; Patel, P.M.; O’Neal, J.L.; Heinrich, B.S. High-intensity compared to moderate-intensity training for exercise initiation, enjoyment, adherence, and intentions: An intervention study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.; Sales, A.; Carlson, L.; Steele, J. A comparison of the motivational factors between CrossFit participants and other resistance exercise modalities: A pilot study. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2016, 9, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, B.A.; Bergman, S.M. What keeps athletes in the gym? Goals, psychological needs, and motivation of CrossFit™ participants. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 16, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, D.P.; Polito, L.F.T.; Foschini, D.; Urtado, C.B.; Otton, R. Motives, Motivation and Exercise Behavioral Regulations in CrossFit and Resistance Training Participants. Psychology 2018, 9, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, B.A.; Bergman, S.M. Relationships Among Goal Contents, Exercise Motivations, Physical Activity, and Aerobic Fitness in University Physical Education Courses. Percept Mot. Ski. 2016, 122, 678–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bycura, D.; Feito, Y.; Prather, C.C. Motivational Factors in CrossFitÆ Training Participation. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2017, 4, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, P.; Woodruff, S.J. Examining the influence of CrossFit participation on body image, self-esteem, and eating behaviours among women. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar]

- Feito, Y.; Heinrich, K.M.; Butcher, S.J.; Poston, W.S.C. High-Intensity Functional Training (HIFT): Definition and Research Implications for Improved Fitness. Sports 2018, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eather, N.; Morgan, P.; Lubans, D. Effects of exercise on mental health outcomes in adolescents: Findings from the CrossFit™ teens randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 26, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, A.C.; Goldsmith, A.; Damon, Z.; Walker, M. The influence of sense of community on the perceived value of physical activity: A cross-context analysis. Leis. Sci. 2016, 38, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman-Sandland, J.; Hawkins, J.; Clayton, D. The role of social capital and community belongingness for exercise adherence: An exploratory study of the CrossFit gym model. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, G.N.; Jasinski, D.; Dunn, S.C.; Fletcher, D. Athlete identity and athlete satisfaction: The nonconformity of exclusivity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, A.J.; Schmader, T.; Sylvester, B.D.; Jung, M.E.; Zumbo, B.D.; Martin, L.J.; Beauchamp, M.R. Effects of social belonging and task framing on exercise cognitions and behavior. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 36, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; Papathomas, A.; Perrier, M.-J.; Smith, B.; Group, S.-S.R. Psychosocial factors associated with physical activity in ambulatory and manual wheelchair users with spinal cord injury: A mixed-methods study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock, C.K.; Poston, W.S.; Heinrich, K.M.; Jahnke, S.A.; Jitnarin, N. The benefits of high-intensity functional training fitness programs for military personnel. Mil. Med. 2016, 181, e1508–e1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baştuğ, G.; ÖZcan, R.; GÜLtekİN, D.; GÜNay, Ö. The effects of Cross-fit, Pilates and Zumba exercise on body composition and body image of women. Int. J. Sport. Exerc. Train. Sci. 2016, 2, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.A.; Drake, N.B.; Carper, M.J.; DeBlauw, J.; Heinrich, K.M. Are changes in physical work capacity induced by high-intensity functional training related to changes in associated physiologic measures? Sports 2018, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, A.F.M.; dos Santos, G.B.; dos Reis, T.; Valerino, A.J.R.; Del Rosso, S.; Boullosa, D.A. Differences in Physical Fitness between Recreational CrossFit® and Resistance Trained Individuals. J. Exerc. Physiol. Online 2016, 19, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, K.M.; Spencer, V.; Fehl, N.; Carlos Poston, W.S. Mission essential fitness: Comparison of functional circuit training to traditional Army physical training for active duty military. Mil. Med. 2012, 177, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawska-Cialowicz, E.; Wojna, J.; Zuwala-Jagiello, J. Crossfit training changes brain-derived neurotrophic factor and irisin levels at rest, after wingate and progressive tests, and improves aerobic capacity and body composition of young physically active men and women. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 66, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feito, Y.; Hoffstetter, W.; Serafini, P.; Mangine, G. Changes in body composition, bone metabolism, strength, and skill-specific performance resulting from 16-weeks of HIFT. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198324. [Google Scholar]

- Paine, J.; Uptgraft, J.; Wylie, R. Command and General Staff College CrossFit Study 2010; Army Command and General Staff Coll: Fort Leavenworth, KS, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, V. A Pilot Study on High Intensity Functional Training in an Adaptive Population. Ph.D. Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhatten, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mockeridge, J.; Lazouras, C.; Gallardo, O.; Kasayama, J. High Intensity Functional Exercise Group Class for Acute Rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, e82–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derikx, T.C.; Brands, I.M.; Goedhart, A.T.; Hoens, W.H.; Heijenbrok–Kal, M.H.; Van Den Berg Emons, R.H. High-volume and high-intensity functional training in patients with multiple sclerosis: A pilot study on feasibility and functional capacity. J. Rehabil. Med.-Clin. Commun. 2022, 5, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindelöf, N. Effects and Experiences of High-Intensity Functional Exercise Programmes among Older People with Physical or Cognitive Impairment; Luleå Tekniska Universitet: Luleå, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K.; Zirkenbach, A.; Muri-Rosenthal, J.; Hardman, J.S. Adaptive and Inclusive Training: A Practical Guide for the Adatpive and Inclusive Trrainer Certification Course; Adaptive Training Academy: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, P.; Taylor, N.; Hindson, L. A pilot investigation of a psychosocial activity coursefor people with spinal cord injuries. Psychol. Health Med. 2006, 11, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporner, M.L.; Fitzgerald, S.G.; Dicianno, B.E.; Collins, D.; Teodorski, E.; Pasquina, P.F.; Cooper, R.A. Psychosocial impact of participation in the national veterans wheelchair games and winter sports clinic. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, A.; Martin Ginis, K.; Pelletier, C.; Ditor, D.; Foulon, B.; Wolfe, D. The effects of exercise training on physical capacity, strength, body composition and functional performance among adults with spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Spinal Cord 2011, 49, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayed, N.; Cieza, A.; Edmond Bickenbach, J. Linking health and health-related information to the ICF: A systematic review of the literature from 2001 to 2008. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 1941–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization 1946. Bull. World Health Organ. 2002, 80, 983. [Google Scholar]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000, 320, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J.V.; King, L. Journeying from the philosophical contemplation of constructivism to the methodological pragmatics of health services research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 40, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.B. When you don’t know what you don’t know: Evaluating workshops and training sessions using the retrospective pretest methods. In Proceedings of the Meeting of the American Evalution Asssocaition Annual Conference, Arlington, VA, USA, 6–9 November 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, C.C.; McGuigan, W.M.; Katzev, A.R. Measuring program outcomes: Using retrospective pretest methodology. Am. J. Eval. 2000, 21, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, C.H.; Albright, K.J.; Lequerica, A. Using the ICF to code and analyse women’s disability narratives. Disabil. Rehabil. 2008, 30, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Shenoy, S.S. Impact of exercise on targeted secondary conditions. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Disability in America: A New Look; The National Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Motl, R.W.; Pilutti, L.A. The benefits of exercise training in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 8, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. WG Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS). 2018. Available online: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/ (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Rubbin, J.; Babbie, B. Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophic and Practical Guide; Falmer Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Turner III, D.W.; Hagstrom-Schmidt, N. Qualitative Interview Design. In Howdy or Hello? Technical and Professional Communication. 2022. Available online: https://oer.pressbooks.pub/howdyorhello/back-matter/appendix-qualitative-interview-design/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, E.H.; Curry, L.A.; Devers, K.J. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 1758–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brantlinger, E.; Jimenez, R.; Klingner, J.; Pugach, M.; Richardson, V. Qualitative studies in special education. Except. Child. 2005, 71, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, K.M.; Kurtz, B.K.; Patterson, M.; Crawford, D.A.; Barry, A. Incorporating a Sense of Community in a Group Exercise Intervention Facilitates Adherence. Health Behav. Res. 2022, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M.C. CrossFit: Fitness cult or reinventive institution? Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2015, 52, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Riley, B.; Wang, E.; Rauworth, A. Accessibility of health clubs for people with mobility disabilities and visual impairments. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 2022–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.J.; Coleman, L.; Babkes Stellino, M. The relationship between basic psychological need satisfaction, behavioral regulation, and participation in CrossFit. J. Sport Behav. 2016, 39, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer, J.H. The conspicuous absence of people with disabilities in public fitness and recreation facilities: Lack of interest or lack of access? Am. J. Health Promot. 2005, 19, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.M.; Nimon, K. Retrospective Pretest: A Practical Technique for Professional Development Evaluation. J. Ind. Teach. Educ. 2007, 44, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, G.S. Response-shift bias: A problem in evaluating interventions with pre/post self-reports. Eval. Rev. 1980, 4, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatt, J.; Taylor-Powell, E. Using the Retrospective Post-Then-Pre-Design; Quick Tips# 27; University of Wisconsin-Extension: Madison, WI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dominski, F.H.; Serafim, T.T.; Siqueira, T.C.; Andrade, A. Psychological variables of CrossFit participants: A systematic review. Sport Sci. Health 2020, 17, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, H.S. Self-selection bias in business ethics research. Bus. Ethics Q. 2006, 16, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Survey Only (n = 28) | Interview + Survey (n = 10) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 15 | 54 | 6 | 60 |

| Male | 13 | 46 | 4 | 40 |

| Age | ||||

| M = 37.7 years (SD = 9.3) Range = 25–58 | M = 45.3 years (SD = 12.6) Range = 26–62 | |||

| 18–34 years | 15 | 54 | 2 | 20 |

| 35–64 years | 13 | 46 | 8 | 80 |

| Race a | ||||

| White race | 13 | 93 | 9 | 90 |

| Not reported | 1 | 7 | 1 | 10 |

| Ethnicity a | ||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latinx | 12 | 86 | 9 | 90 |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| Employment a | ||||

| Full time | 13 | 93 | 4 | 40 |

| Other/not specified | 1 | 7 | 6 | 60 |

| Primary Disability Category | ||||

| Congenital (e.g., limb difference) | 5 | 18 | 1 | 10 |

| Health impairment (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| Injury (e.g., spinal cord injury, amputation) | 13 | 46 | 4 | 40 |

| Neurological (e.g., cerebral palsy) | 10 | 36 | 4 | 40 |

| Age of disability onset b | M = 23.4 years (SD = 22.2) Range birth to 56 yrs. | |||

| Length of time of having primary disability b | ||||

| M = 21.9 years (SD = 17.1) Range, 1–56 yrs. | ||||

| Length of HIFT participation | ||||

| M = 4.2 yrs.; SD = 2.9 Range, 3 mo. to 12 yrs. | M = 3.3 yrs.; SD = 2.4 yrs. Range, 7 mo. to 9.1 yrs. | |||

| Subtheme/Quotes (Participant Identifier; Disability Category) |

|---|

| Physical Health |

| “My blood sugar was never high anymore. My A1C’s down to 5.3, which is normal.” (AA-02, injury) * |

| “Avoided physical therapy by strengthening my whole body through [HIFT]” (AA-53, congenital) |

| “I have a rare disease called Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, [HIFT] has allowed me to gain muscle I was not born with and also keep my disease maintained from progressing. Weight loss and even success with my surgeries and treatments. My heart health has improved, and it calms my nerve pain and improves its function.” (AA-68, congenital) |

| “Every time I go to the doctor I get told that I have the best vitals/blood work they’ve seen all day.” (AA-06, neurological) |

| “[Increased] strength to lift, carry, or drag items” (AA-55, congenital) |

| “Since starting [HIFT], my MS symptoms have minimized. My gait and balance have drastically improved. I am no longer falling. My walking speed is much faster. I also experience less fatigue and brain fog” (AA-01, neurological) |

| “Health-wise it has given me more stamina, more strength. It has corrected a curving spine” (AA-05, injury) |

| “I have better balance and strength. More than I ever have had. I have had 8 surgeries (joint replacements & fusions) due to my RA [rheumatoid arthritis]. I have osteoporosis and I have COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], but I feel GREAT. I can do things I never thought I could, like bench presses, wall balls, etc. The coaches work with me to adapt to my physical limitations” (AA-04, health impairment) |

| Functional Health |

| “But I think what [HIFT] has helped, is if I would unload the dishwasher, it would take me hours to recuperate, or maybe a day to recuperate from doing the dishes. And now, I’m cooking, I’m cleaning up afterwards, I empty the dishwasher.” (AA-02, injury) * |

| “It has given me more energy and helped me be more independent on my own. Example: I can now put my chair in and out of my car on my own. And I can stand assisted for longer periods of time.” (AA-06, neurological) |

| “Opening doors. I always used to struggle opening door handles. But I’ve got the ability now. And the technique of being able to actually open the door, door handle and pull the door, shut the door. Obviously, just wheeling around the house is a lot easier than it used to be.” (AA-05, injury) * |

| “[HIFT] has allowed me to take care of some of my own needs without so much relying on somebody else.” (AA-02, injury) * |

| “I think [HIFT] is a great path to getting that autonomy. Anytime you can get more function, more strength, and you’re not relying on somebody else, you have more options.” (AA-03, injury) * |

| “I couldn’t do wheelchair ramps before. And now I go up wheelchair ramps like they’re flat.” (AA-02, injury) * |

| “I credit [HIFT] for being able to continue working, and for my ongoing general physical and mental wellness.” (AA-09, neurological) |

| “[HIFT has] been especially helpful in my daily life as a wheelchair user. My strength is important to do transfers properly and my endurance is important to continue to live independently.” (AA-51, injury) |

| “I am much stronger, have better balance, and better ability to live my life the way I want. I strongly believe [HIFT] has played a major role in my strength and independence, at this point as my disease progresses.” (AA-09, neurological) |

| “Improves strength, balance, and endurance, which affects my capability to improve and accomplish all ADLs [activities of daily living].” (AA-59, injury) |

| Quotes (Participant Identifier; Disability Category) |

|---|

| “For me it’s mental, the physical aspect is secondary.” (AA-106, congenital) |

| “And to increase my self-esteem and confidence. I am learning how to know my own body within by knowing when to push, and when not to.” (AA-58, neurological) |

| “[HIFT] has helped me believe in myself again unlike anything else I’ve done.” (AA-101, Injury) |

| “Outside the gym, [HIFT] has given me many coping strategies to handle day to day life.” (AA-09, neurological) |

| “[HIFT] has given me tremendous confidence again, [HIFT] seems to be a family and not just people at the gym.” (AA-02, injury) * |

| “I’m 40 years old. I lived 38 of those years lacking confidence, and self-esteem because I’m different. [HIFT], specifically my [gym] gave me an opportunity to shine and be my best self.” (AA-07, congenital) * |

| “Significant reduction in fatigue and depression.” (AA-01, neurological) |

| “[HIFT] keeps me happy and sane. My job can be very stressful. And working out at the end of the day is a stress reliever. It refreshes me and energizes me.” (AA-09, neurological) |

| “Helps with anxiety and depression and PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder].” (AA-106, congenital) |

| Subtheme/Quotes (Participant Identifier; Disability Category) |

|---|

| General Social Support/Affiliation |

| “The social aspect of the [HIFT] community is the best around. I work out 4–5 days a week at my gym as the only adaptive athlete. Nobody there cares or treats me differently outside of offering help to get gear set up.” (AA-08, injury) |

| “[HIFT] provided a sense of community and comradery that really helped me at the time. The gym was very inclusive and supportive of me.” (AA-103, Injury) |

| “And it’s more of a family the way people cheer you on and root you on, and they want to see you succeed. It’s not like going to the gym—it’s not like that. There’s a whole community [in HIFT]” (AA-02, injury) * |

| “[HIFT] has also made my confidence skyrocket thanks to the ability to do workouts with other people. Even though I might have a shorter run or do step-ups instead of box jumps, the workouts still feel like I’m working with the group and pushing myself.” (AA-50, congenital) |

| “The social support of the community has been huge, and my ability to be around other adaptive athletes has been important in my mental and physical health.” (AA-09, neurological) |

| “As a person with a spinal cord injury who lives all day in a wheelchair, I am always viewed differently by the general public. They feel that we are weak, always need help, and someone to feel sorry for. The HIFT community helps show you none of that is true. That is a huge benefit to anybody’s mental health.” (AA-08, injury) |

| “They’ve never looked at me as just a person in a wheelchair. I’m just one of I am one of the members.” (AA-05, injury) * |

| Relationships with HIFT Trainers |

| “The owner of our gym messaged back to me was like, ‘Hey, I’ve never worked with a person in a wheelchair, but I’ll give it a try. Come on in.’ In my 4 years of doing [HIFT] I have had zero injuries since I have coaches that make sure I do not overuse certain muscles. They make sure that my workouts stay varied, so nothing is overused.” (AA-08, injury) * |

| “Unlike a lot of places where, when I roll in immediately the owners are nervous that I’m setting them up for some sort of action under the Americans with Disabilities Act. And in the [HIFT] box, [they] were welcoming us. There weren’t any coaches that you could sense hostility from. They all seem to embrace us being there.” (AA-03, injury) |

| “[My HIFT] has an incredible coaching staff with a decade of programming and [HIFT] coaching experience. They have navigated my needs as an adaptive athlete and have a lot to do with all of the progress I’ve made since joining their gym in August 2019.” (AA-60 neurological) |

| “Especially with being a quadriplegic and having more weight on me than I wanted, it’s really not easy to get in and out of your chair. [My trainer] had never worked with a person in a wheelchair before, but he was all for learning. And I’ll never forget, he treated me no different than he does any other new member who comes in—he literally had me do the exact same workout that he has everybody else do. He actually had me getting out of my wheelchair, which I hadn’t voluntarily done in probably 10 years.” (AA-08, injury) * |

| Social Media |

| “Through Instagram I found other adaptive athletes doing [HIFT] and that was the most eye-opening experience. I’ve made friends with other adaptive athletes by sharing our stories and how we adapt to different movements.” (AA-07, congenital) * |

| “The friends I have made from [HIFT Competitions] and through social media that are all in the same situation as me is great.” (AA-08, injury) |

| “So, I first got started [on Instagram]. And I found all these really great athletes like [names omitted], they both have missing limbs. And I was like, whoa, wait, this kid is climbing a rope. I found all these other really amazing athletes that were just like me, and I’m like, ‘Alright, so I can do this!’” (AA-07, congenital) * |

| Inclusive Competitions |

| “Being able to compete even with adaptive movements has given me the chance to train with people and not be excluded.” (AA-05, injury) |

| “Through the recent announcement of including adaptive athletes—I have the chance to compete with others just like me. I’ve never been able to do that. Ever.” (AA-07, congenital) * |

| Integrated Classes |

| “[HIFT] is more than just about working out and getting fit. It is about a community of people who support each other. It’s a group of people who all look to me as an equal and not a disabled person. That helps everyone’s mental health but especially people with a spinal cord injury since we are viewed differently.” (AA-08, injury) |

| “No, we just have a really special [gym], because it has an adapted focus, and I call it the land of misfit toys because we kind of joke that we assume everyone is adaptive until proven differently.” (AA-01, neurological) * |

| “Even though I am an adaptive athlete, people treat me and push me the same as any other athlete.” (AA-06, neurological) * |

| Quotes (Participant Identifier; Disability Category) |

|---|

| “I have a custom-made jump rope. It’s got an attachment that goes around my left arm that can be tightened. And so that I jump right when I jump rope, it looks very much like an able-bodied person jump roping.” (AA-07, congenital) * |

| “I’ve made my own wheelie bar, that is a very heavy-duty wheelie bar. So that whenever I’m lifting up anything overhead, I can’t flip or anything else to hurt myself.” (AA-08, injury) |

| “[The box I’m at now], he purposefully designed it so it could be wheelchair accessible.” (AA-01, neurological) * |

| “We’ve gone through a couple variations of attachment to the rig. What I currently use is a construction strap, looping around the rig and I can jump into it.” (AA-07, congenital) * |

| “And so, whenever the gym got a SkiErg, I of course cannot fit in my wheelchair. So, I took two old belts that I had that were Canvas belts looped them around the handles, then use those as kind of extensions.” (AA-08, injury) * |

| Quotes (Participant Identifier; Disability Category) |

|---|

| “I think [HIFT] should have been introduced to people of all disabilities a long time ago. It should be a coordinated effort between healthcare and [HIFT] training.” (AA-04, health impairment) |

| “I have been told over and over again by doctors that [HIFT] is dangerous, that I shouldn’t do it, that I won’t be able to do many of the movements. Quite to the contrary, over and over I prove them wrong. While my body requires constant maintenance and my capabilities are changing as my condition progresses, [HIFT] has given me the strength and the tools to maintain a high level of health and fitness. Doctors should spend more time understanding what [HIFT] actually is, and the positive benefits (physical and mental) of doing it and being a part of the community.” (AA-09, neurological) |

| “As soon as I started doing [HIFT], I thought it should be included in the recovery of any spinal cord injury program.” (AA-51, injury) |

| “I would like for healthcare providers to know—when done correctly and adapted with a knowledgeable coach—the physical and emotional benefits of [HIFT] far outweigh any medication.” (AA-10, neurological) |

| “[HIFT] is/was the single most important contributory factor in my recovery from amputation.” (AA-72, injury) |

| “Doctors don’t understand how [HIFT] is important with my neurological problem and I’m really frustrated that healthcare system does not understand how good it is.” (AA-74, neurological) |

| “Each person can start out with traditional therapy mixed with some [HIFT] and gradually work towards exclusively [HIFT] that can be maintained once they leave rehab and are at home.” (AA-59, injury) |

| “I don’t really think that there’s any disability out there that wouldn’t benefit in some way from [HIFT].” (AA-06, neurological) * |

| “[HIFT] has kept me functional and well far better than any experience I’ve had with doctors or physical therapy. My neurologist is consistently impressed by my strength, independence, and balance.” (AA-09, neurological) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koon, L.M.; Hall, J.P.; Arnold, K.A.; Donnelly, J.E.; Heinrich, K.M. High-Intensity Functional Training: Perceived Functional and Psychosocial Health-Related Outcomes from Current Participants with Mobility-Related Disabilities. Sports 2023, 11, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11060116

Koon LM, Hall JP, Arnold KA, Donnelly JE, Heinrich KM. High-Intensity Functional Training: Perceived Functional and Psychosocial Health-Related Outcomes from Current Participants with Mobility-Related Disabilities. Sports. 2023; 11(6):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11060116

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoon, Lyndsie M., Jean P. Hall, Kristen A. Arnold, Joseph E. Donnelly, and Katie M. Heinrich. 2023. "High-Intensity Functional Training: Perceived Functional and Psychosocial Health-Related Outcomes from Current Participants with Mobility-Related Disabilities" Sports 11, no. 6: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11060116

APA StyleKoon, L. M., Hall, J. P., Arnold, K. A., Donnelly, J. E., & Heinrich, K. M. (2023). High-Intensity Functional Training: Perceived Functional and Psychosocial Health-Related Outcomes from Current Participants with Mobility-Related Disabilities. Sports, 11(6), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11060116