Molecular Cloning and Characterization of G Alpha Proteins from the Western Tarnished Plant Bug, Lygus hesperus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Insect Rearing

2.2. Identification and Cloning of L. hesperus Gα Subunits

| Primer | Sequence (5'–3') | Primer | Sequence (5'–3') | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ga deg 1 F | ACNATNGTNAARCARATG (TIVKQM) | Degenerate PCR | LhGao 679 F | CGACGTGATACAGAGGATG | Transcriptional Expression Profiling |

| Ga deg 2 F | GAYGTNGGNGGNCARYG (DVGGQR) | LhGao 1,211 R | TTGTCAATGGCGACTTCTT | ||

| Ga deg 3 F | AARTGGATHCAYTGYTT (KWIHCF) | LhGai 499 F | AACTACGTTCCAACTCAGC | ||

| Ga deg 1a R | RTCTTYTTRTTNAGRAA (FLNKKD) | LhGai 1,026 R | ATCAGTGACAGCATCGAAG | ||

| Ga deg 1b R | RTCYTGYTTRTTNAGRAA (FLNKQD) | LhGas 331 F | GTCCGCGTCGACTATATAC | ||

| Ga deg 2 R | TCNGTNACNGCRTCRAANAC (VFDAVTD) | LhGas 862 R | CCTTGATCTTCTCTGCCAG | ||

| LhGaq 468 F1 | GGAAATCGATAGAGTGGCAG | ||||

| LhGai sp F2 | CAAGTGGTTTGTCGAGACTTCC | 5' & 3' RACE | LhGaq 474 F2 | GGCGAGAATAGAGAGTCCAG | |

| LhGai sp R1 | CATCTTCTGCAAGTACTAGGTCGT | LhGaq 1,036 R1 | AAGGTTGTACTCCTTGAGATTT | ||

| LhGai sp R2 | TGTTAGTGTCAGTAGCGCAGGT | LhGaq 1,035 R2 | CTAGATTGAATTCTTTGAGTGCA | ||

| LhGai sp F2b | GGTTCCAATACGTATGAAGAAGCAG | LhGa12/13 307 F | TTGAGCCGGAATTGATCAA | ||

| LhGaq2 F1 | TCCTTGTCGCGCTCAGTGAATACG | LhGa12/13 834 R | CCACGAGAACTTGATCGAA | ||

| LhGaq2 F2 | TCGAATCGGAAAATGAGAACCGAATGGA | ||||

| LhGaq2 R1 | GGACGAGTGCTGGAACCAGGGGTA | LH Gas no stop R | TAGCAACTCATATTGGCG | Cellular Localization | |

| LhGaq2 R2 | TCCATTCGGTTCTCATTTTCCGATTCGA | LhGaq no stop R | AACAAGGTTGTACTCCTTGAGA | ||

| LhGas F1 | CCGCCATCATATTCGTGACCGCCT | LH Gi no stop R | GAATAGGCCACAATTTTTTAAGTTT | ||

| LhGas F2 | AAGACCCCACGCAGAACCGTCTCA | ||||

| LhGas R1 | TGAGACGGTTCTGCGTGGGGTCTT | ||||

| LhGas R2 | AGGCGGTCACGAATATGATGGCGG | ||||

| LhGas + stop R | TTATAGCAACTCATATTGGCG | Full Length Clones | |||

| LH Gas start F | AAATCGTCATGGGGTGC | ||||

| LhGaq start F | AGATGGCGTGCTGTTTG | ||||

| LhGaq end R | TTAAACAAGGTTGTACTCCTTGAGA | ||||

| LhGi start F | TAATGGGTTGCGCGATCAG | ||||

| LhGi end R | TTAGAATAGGCCACAATTTTTTAAGTTT | ||||

| LhGao start F | ATGGGCTGTGCAATGTCTG | ||||

| LhGao stop R | TTAGTAAAGTCCACAACC | ||||

| LhGa12/13 start | ATGGCGAGTGATATATTTTG | ||||

| LhGa12/13 stop | TCATTGCAACATGAGGGAT |

2.3. Bioinformatic Analyses

2.4. Transcriptional Profiling of L. hesperus Gα Subunits

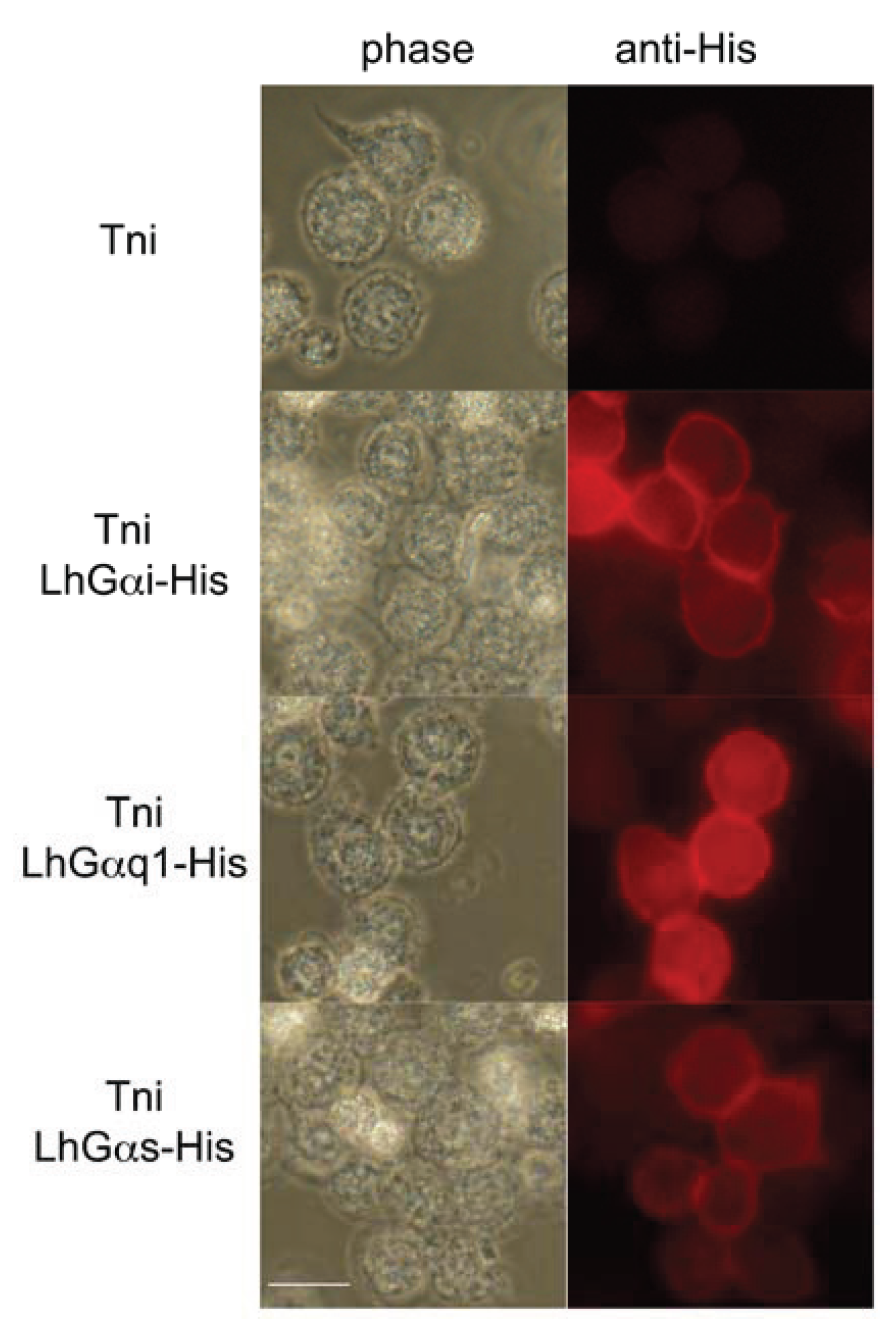

2.5. Immunocytochemical Localization of L. hesperus Gα in Cultured Insect Cells

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of L. hesperus Gα Sequences

| Query | Description | Accession | E Value | % identity | % positives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LhGαs | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(s) subunit alpha [Zootermopsis nevadensis] | KDR14965.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 340/379 (90%) | 359/379 (94%) |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(s) subunit alpha [Diaphorina citri] | XP_008468199.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 338/380 (89%) | 360/380 (94%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(s) subunit alpha [Acyrthosiphon pisum] | XP_001944148.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 335/380 (88%) | 362/380 (95%) | |

| guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha stimulating activity polypeptide [Daphnia pulex] | EFX88427.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 330/379 (87%) | 359/379 (94%) | |

| guanine nucleotide-binding protein G, putative [Pediculus humanus corporis] | XP_002431834.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 331/380 (87%) | 355/380 (93%) | |

| LhGαi | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(i) subunit alpha [Zootermopsis nevadensis] | KDR22153.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 321/355 (90%) | 339/355 (95%) |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(i) subunit alpha-like [Megachile rotundata] | XP_003707938.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 314/355 (88%) | 333/355 (93%) | |

| PREDICTED: G protein alpha i subunit [Tribolium castaneum] | XP_008200240.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 313/355 (88%) | 331/355 (93%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(i) subunit alpha-like [Apis mellifera] | XP_395172.2 | 0.00E + 00 | 311/355 (88%) | 331/355 (93%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(i) subunit alpha-like [Bombus terrestris] | XP_003393073.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 310/355 (87%) | 330/355 (92%) | |

| LhGαq1 | GTP-binding protein alpha subunit, gna [Anopheles sinensis] | KFB50356.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 336/353 (95%) | 343/353 (97%) |

| AGAP005079-PI [Anopheles gambiae str. PEST] | XP_313956.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 336/353 (95%) | 343/353 (97%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha isoform X1 [Acyrthosiphon pisum] | XP_001948628.2 | 0.00E + 00 | 333/353 (94%) | 346/353 (98%) | |

| GTP-binding protein alpha subunit, gna [Aedes aegypti] | XP_001660884.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 335/353 (95%) | 343/353 (97%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha-like isoform 1 [Megachile rotundata] | XP_003702524.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 335/353 (95%) | 344/353 (97%) | |

| LhGαq2 | PREDICTED: G protein alpha q subunit isoform X2 [Acyrthosiphon pisum] | XP_008178833.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 322/353 (91%) | 337/353 (95%) |

| AGAP005079-PB [Anopheles gambiae str. PEST] | XP_001688493.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 325/353 (92%) | 334/353 (94%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha-like isoform 5 [Megachile rotundata] | XP_003702528.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 318/353 (90%) | 338/353 (95%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha-like isoform X5 [Apis mellifera] | XP_006562642.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 319/353 (90%) | 334/353 (94%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha-like isoform X13 [Apis dorsata] | XP_006615865.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 318/353 (90%) | 333/353 (94%) | |

| LhGαq3 | PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha-like isoform 2 [Megachile rotundata] | XP_003702525.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 334/353 (95%) | 343/353 (97%) |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha isoform X3 [Acyrthosiphon pisum] | XP_008178834.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 331/353 (94%) | 345/353 (97%) | |

| AGAP005079-PF [Anopheles gambiae str. PEST] | XP_001688489.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 333/353 (94%) | 343/353 (97%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha-like isoform X8 [Apis mellifera] | XP_623211.2 | 0.00E + 00 | 328/353 (93%) | 341/353 (96%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha-like isoform 1 [Megachile rotundata] | XP_003702524.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 325/353 (92%) | 338/353 (95%) | |

| LhGαq4 | PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha-like isoform 3 [Megachile rotundata] | XP_003702526.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 324/353 (92%) | 334/353 (94%) |

| G protein alpha q isoform 2 [Bombyx mori] | NP_001128385.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 322/353 (91%) | 335/353 (94%) | |

| PREDICTED: G protein alpha q subunit isoform X4 [Acyrthosiphon pisum] | XP_008178835.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 320/353 (91%) | 336/353 (95%) | |

| GTP-binding protein alpha subunit, gna [Aedes aegypti] | XP_001660885.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 322/353 (91%) | 334/353 (94%) | |

| AGAP005079-PD [Anopheles gambiae str. PEST] | XP_001688487.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 322/353 (91%) | 334/353 (94%) | |

| LhGαq5 | PREDICTED: G protein alpha q subunit-like [Diaphorina citri] | XP_008479779.1 | 4.00E − 102 | 145/157 (92%) | 151/157 (96%) |

| PREDICTED: G protein alpha q subunit isoform X4 [Acyrthosiphon pisum] | XP_008178835.1 | 2.00E − 99 | 152/193 (79%) | 155/193 (80%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha-like isoform 3 [Megachile rotundata] | XP_003702526.1 | 2.00E − 99 | 153/193 (79%) | 155/193 (80%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha isoform X3 [Tribolium castaneum] | XP_008195246.1 | 1.00E − 98 | 152/193 (79%) | 155/193 (80%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha isoform X5 [Acyrthosiphon pisum] | XP_008178836.1 | 2.00E − 98 | 152/193 (79%) | 155/193 (80%) | |

| LhGα12 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha-like protein [Harpegnathos saltator] | EFN86700.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 287/367 (78%) | 327/367 (89%) |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha homolog [Apis mellifera] | XP_394382.2 | 0.00E + 00 | 286/367 (78%) | 326/367 (88%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha homolog [Nasonia vitripennis] | XP_001600076.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 282/363 (78%) | 324/363 (89%) | |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha-like protein [Acromyrmex echinatior] | EGI64184.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 288/368 (78%) | 328/368 (89%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha homolog [Bombus terrestris] | XP_003402866.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 283/367 (77%) | 325/367 (88%) | |

| LhGαo | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(o) subunit alpha [Locusta migratoria] | P38404.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 346/354 (98%) | 349/354 (98%) |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(o) subunit alpha [Zootermopsis nevadensis] | KDR16702.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 345/354 (97%) | 348/354 (98%) | |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(o) subunit alpha [Camponotus floridanus] | EFN66163.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 344/354 (97%) | 348/354 (98%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(o) subunit alpha-like isoform 1 [Megachile rotundata] | XP_003701784.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 342/354 (97%) | 347/354 (98%) | |

| PREDICTED: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(o) subunit alpha [Microplitis demolitor] | XP_008545405.1 | 0.00E + 00 | 339/354 (96%) | 346/354 (97%) |

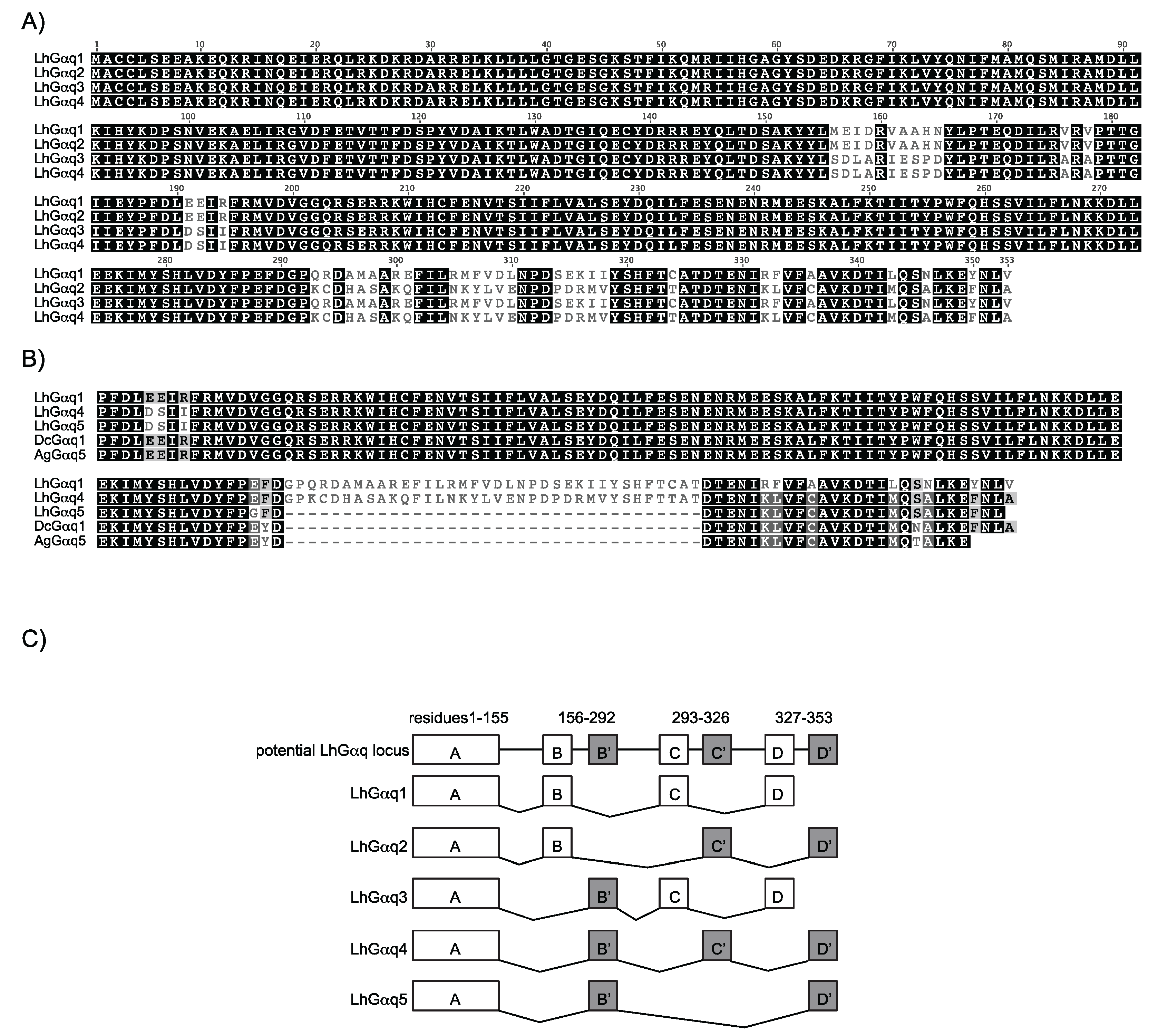

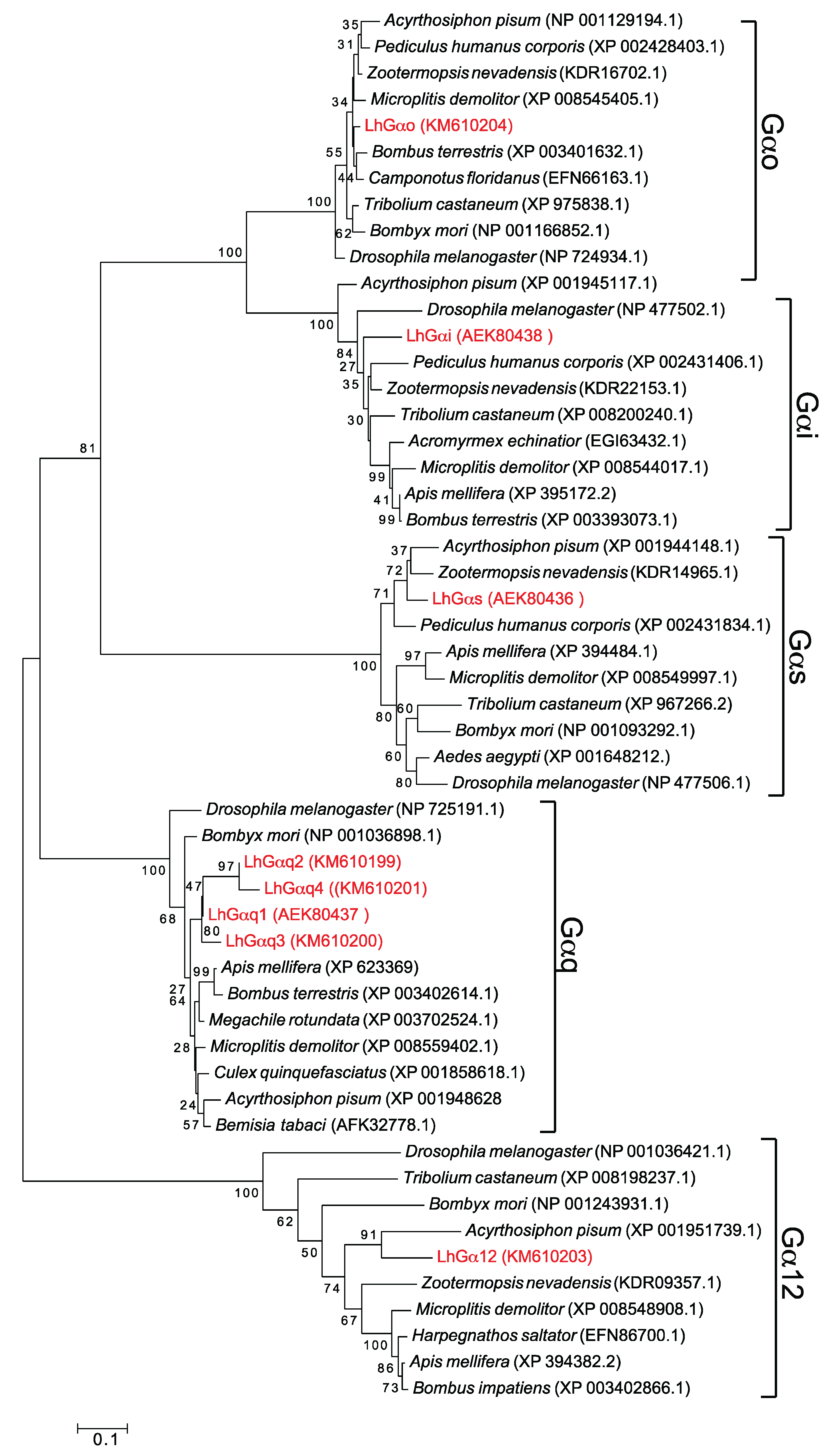

3.2. Bioinformatic Analysis of LhGα Subunits

| LhGαq1 | LhGαq2 | LhGαq3 | LhGαq4 | LhGαq5 | LhGαs | LhGαi | LhGαo | LhGα12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LhGαq1 | 100 | 93 | 96 | 89 | 72 | 42 | 49 | 48 | 44 |

| LhGαq2 | 93 | 100 | 89 | 96 | 75 | 42 | 47 | 46 | 44 |

| LhGαq3 | 96 | 89 | 100 | 93 | 78 | 42 | 50 | 48 | 45 |

| LhGαq4 | 89 | 96 | 93 | 100 | 81 | 42 | 48 | 46 | 44 |

| LhGαq5 | 72 | 75 | 78 | 81 | 100 | 39 | 47 | 47 | 43 |

| LhGαs | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 39 | 100 | 41 | 42 | 35 |

| LhGαi | 49 | 47 | 50 | 48 | 47 | 41 | 100 | 67 | 38 |

| LhGαo | 48 | 46 | 48 | 46 | 47 | 42 | 67 | 100 | 39 |

| LhGα12 | 44 | 44 | 45 | 44 | 43 | 35 | 38 | 39 | 100 |

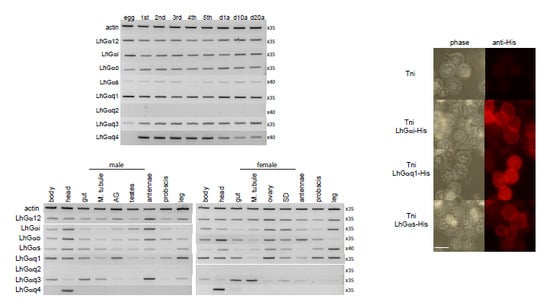

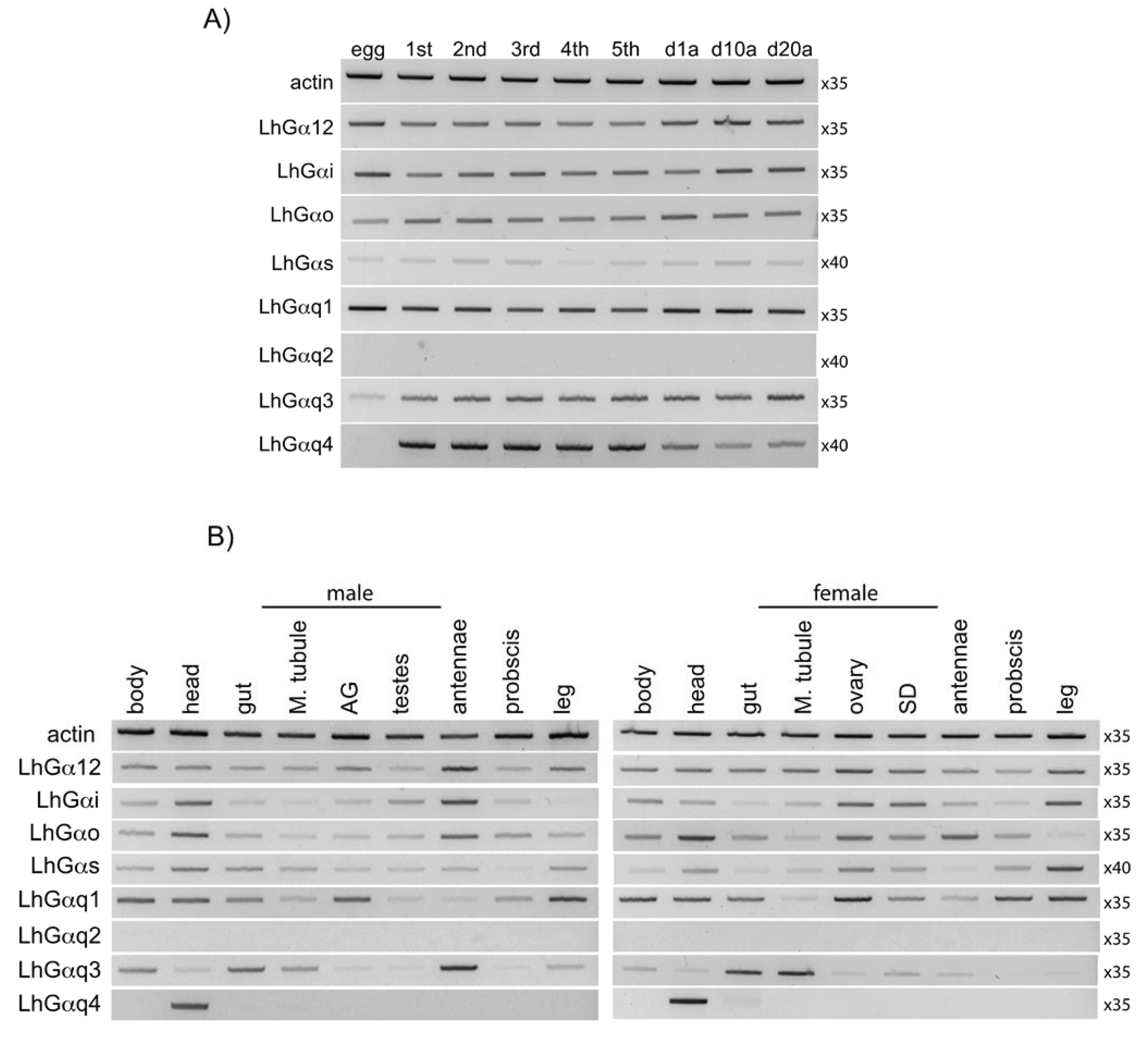

3.3. End Point PCR-Based Transcriptional Expression Profiling

3.4. Intracellular Localization of Transiently Expressed LhGα Subunits

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Offermanns, S. G-proteins as transducers in transmembrane signalling. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2003, 83, 101–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Vera, T.M.; Vanhauwe, J.; Thomas, T.O.; Medkova, M.; Preininger, A.; Mazzoni, M.R.; Hamm, H.E. Insights into G protein structure, function, and regulation. Endocr. Rev. 2003, 24, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldham, W.M.; Hamm, H.E. Structural basis of function in heterotrimeric G proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2006, 39, 117–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, P.; Casey, P.J.; Meigs, T.E. Biologic functions of the G12 subfamily of heterotrimeric g proteins: Growth, migration, and metastasis. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 6677–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worzfeld, T.; Wettschureck, N.; Offermanns, S. G12/G13-mediated signalling in mammalian physiology and disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008, 29, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, T.; Vosshall, L.B. Controversy and consensus: Noncanonical signaling mechanisms in the insect olfactory system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009, 19, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stengl, M.; Funk, N.W. The role of the coreceptor Orco in insect olfactory transduction. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2013, 199, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistrand, M.; Käll, L.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L. A general model of G protein-coupled receptor sequences and its application to detect remote homologs. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, R.; Sachse, S.; Michnick, S.W.; Vosshall, L.B. Atypical membrane topology and heteromeric function of Drosophila odorant receptors in vivo. PLOS Biol. 2006, 4, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundin, C.; Käll, L.; Kreher, S.A.; Kapp, K.; Sonnhammer, E.L.; Carlson, J.R.; von Heijne, G.; Nilsson, I. Membrane topology of the Drosophila OR83b odorant receptor. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 5601–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-J.; Anderson, A.R.; Trowell, S.C.; Luo, A.-R.; Xiang, Z.-H.; Xia, Q.-Y. Topological and functional characterization of an insect gustatory receptor. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e24111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, J.J.; Hoffmann, E.J.; Perera, O.P.; Snodgrass, G.L. Identification of the western tarnished plant bug (Lygus hesperus) olfactory co-receptor Orco: Expression profile and confirmation of atypical membrane topology. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 81, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Pellegrino, M.; Nakagawa, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Vosshall, L.B.; Touhara, K. Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature 2008, 452, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, R.; Kiely, A.; Beale, M.; Vargas, E.; Carraher, C.; Kralicek, A.V.; Christie, D.L.; Chen, C.; Newcomb, R.D.; Warr, C.G. Drosophila odorant receptors are novel seven transmembrane domain proteins that can signal independently of heterotrimeric G proteins. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 38, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Tanaka, K.; Touhara, K. Sugar-regulated cation channel formed by an insect gustatory receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11680–11685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicher, D.; Schäfer, R.; Bauernfeind, R.; Stensmyr, M.C.; Heller, R.; Heinemann, S.H.; Hansson, B.S. Drosophila odorant receptors are both ligand-gated and cyclic-nucleotide-activated cation channels. Nature 2008, 452, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talluri, S.; Bhatt, A.; Smith, D.P. Identification of a Drosophila G protein alpha subunit (dGq alpha-3) expressed in chemosensory cells and central neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 11475–11479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquin-Joly, E.; Francois, M.-C.; Burnet, M.; Lucas, P.; Bourrat, F.; Maida, R. Expression pattern in the antennae of a newly isolated lepidopteran Gq protein alpha subunit cDNA. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 2133–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, N.; Atsumi, S.; Tabunoki, H.; Sato, R. Expression and localization of three G protein alpha subunits, Go, Gq, and Gs, in adult antennae of the silkmoth (Bombyx mori). J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 485, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rützler, M.; Lu, T.; Zwiebel, L.J. Galpha encoding gene family of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae: Expression analysis and immunolocalization of AGalphaq and AGalphao in female antennae. J. Comp. Neurol. 2006, 499, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boto, T.; Gomez-Diaz, C.; Alcorta, E. Expression analysis of the 3 G-protein subunits, Galpha, Gbeta, and Ggamma, in the olfactory receptor organs of adult Drosophila melanogaster. Chem. Senses 2010, 35, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Farhat, K.; Oberland, S.; Gisselmann, G.; Neuhaus, E.M. The stimulatory Gα(s) protein is involved in olfactory signal transduction in Drosophila. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e18605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegelberger, G.; van den Berg, M.J.; Kaissling, K.E.; Klumpp, S.; Schultz, J.E. Cyclic GMP levels and guanylate cyclase activity in pheromone-sensitive antennae of the silkmoths Antheraea polyphemus and Bombyx mori. J. Neurosci. 1990, 10, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boekhoff, I.; Seifert, E.; Göggerle, S.; Lindemann, M.; Krüger, B.-W.; Breer, H. Pheromone-induced second-messenger signaling in insect antennae. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1993, 23, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Diaz, C.; Martin, F.; Alcorta, E. The cAMP transduction cascade mediates olfactory reception in Drosophila melanogaster. Behav. Genet. 2004, 34, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Roman, G.; Hardin, P.E. Go contributes to olfactory reception in Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Physiol. 2009, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, J.S.I.; Katanayeva, N.; Katanaev, V.L.; Galizia, C.G. Role of G o/i subgroup of G proteins in olfactory signaling of Drosophila melanogaster. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 39, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalidas, S.; Smith, D.P. Novel genomic cDNA hybrids produce effective RNA interference in adult Drosophila. Neuron 2002, 33, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kain, P.; Chakraborty, T.S.; Sundaram, S.; Siddiqi, O.; Rodrigues, V.; Hasan, G. Reduced odor responses from antennal neurons of G(q)alpha, phospholipase Cbeta, and rdgA mutants in Drosophila support a role for a phospholipid intermediate in insect olfactory transduction. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 4745–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Q.; Sato, H.; Murata, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Ozaki, M.; Nakamura, T. Contribution of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate transduction cascade to the detection of “bitter” compounds in blowflies. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A 2009, 153, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimoto, H.; Takahashi, K.; Ueda, R.; Tanimura, T. G-protein gamma subunit 1 is required for sugar reception in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 3259–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, K.; Kohatsu, S.; Clay, C.; Forte, M.; Isono, K.; Kidokoro, Y. Gsalpha is involved in sugar perception in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 6143–6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kain, P.; Badsha, F.; Hussain, S.M.; Nair, A.; Hasan, G.; Rodrigues, V. Mutants in phospholipid signaling attenuate the behavioral response of adult Drosophila to trehalose. Chem. Senses 2010, 35, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredendiek, N.; Hütte, J.; Steingräber, A.; Hatt, H.; Gisselmann, G.; Neuhaus, E.M. Goa is involved in sugar perception in Drosophila. Chem. Senses 2011, 36, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.A.; Carlson, J.R. Role of G-proteins in odor-sensing and CO2-sensing neurons in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 4562–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devambez, I.; Agha, M.A.; Mitri, C.; Bockaert, J.; Parmentier, M.-L.; Marion-Poll, F.; Grau, Y.; Soustelle, L. Gαo is required for l-canavanine detection in Drosophila. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, D.R. An annotated listing of host plants of Lygus hesperus Knight. Entomol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1977, 23, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Young, O.P. Host plants of the tarnished plant bug, Lygus lineolaris (Heteroptera: Miridae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1986, 79, 747–762. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmer, J.L.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Byers, J.A.; Shope, K.L.; Smith, J.P. Behavioral response of Lygus hesperus to conspecifics and headspace volatiles of alfalfa in a Y-tube olfactometer. J. Chem. Ecol. 2004, 30, 1547–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackmer, J.L.; Canas, L.A. Visual cues enhance the response of Lygus hesperus (Heteroptera: Miridae) to volatiles from host plants. Environ. Entomol. 2005, 34, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Blackmer, J.L.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Zhu, S. Plant volatiles influence electrophysiological and behavioral responses of Lygus hesperus. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers, J.A.; Fefer, D.; Levi-Zada, A. Sex pheromone component ratios and mating isolation among three Lygus plant bug species of North America. Naturwissenschaften 2013, 100, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, J.J.; Geib, S.M.; Fabrick, J.A.; Brent, C.S. Sequencing and de novo assembly of the western tarnished plant bug (Lygus hesperus) transcriptome. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e55105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhaes, L.C.; van Kretschmar, J.B.; Donohue, K.V.; Roe, R.M. Pyrosequencing of the adult tarnished plant bug, Lygus lineolaris, and characterization of messages important in metabolism and development. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2013, 146, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.J.; Perera, O.P.; Snodgrass, G.L. Cloning and expression profiling of odorant-binding proteins in the tarnished plant bug, Lygus lineolaris. Insect Mol. Biol. 2014, 23, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, J.J.; Chaney, K.; Geib, S.M.; Fabrick, J.A.; Brent, C.S.; Walsh, D.; Lavine, L.C. Transcriptome-based identification of ABC transporters in the western tarnished plant bug Lygus hesperus. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickens, J.C.; Callahan, F.E.; Wergin, W.P.; Murphy, C.A.; Vogt, R.G. Intergeneric distribution and immunolocalization of a putative odorant-binding protein in true bugs (Hemiptera, Heteroptera). J. Exp. Biol. 1998, 201, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quan, F.; Forte, M.A. Two forms of Drosophila melanogaster Gs alpha are produced by alternate splicing involving an unusual splice site. Mol. Cell Biol. 1990, 10, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.J.; Dobbs, M.B.; Verardi, M.L.; Hyde, D.R. dgq: A Drosophila gene encoding a visual system-specific G alpha molecule. Neuron 1990, 5, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, S.; Wieschaus, E. The Drosophila gastrulation gene concertina encodes a Gα-like protein. Cell 1991, 64, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, J.J.; Kajigaya, R.; Imai, K.; Matsumoto, S. The Bombyx mori sex pheromone biosynthetic pathway is not mediated by cAMP. J. Insect Physiol. 2007, 53, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, J.J.; Lee, J.M.; Matsumoto, S. Gqalpha-linked phospholipase Cbeta1 and phospholipase Cgamma are essential components of the pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide (PBAN) signal transduction cascade. Insect Mol. Biol. 2010, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horgan, A.M.; Lagrange, M.T.; Copenhaver, P.F. A developmental role for the heterotrimeric G protein Go alpha in a migratory population of embryonic neurons. Dev. Biol. 1995, 172, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raming, K.; Krieger, J.; Breer, H. Molecular cloning, sequence and expression of cDNA encoding a G 0-protein from insect. Cell. Signal. 1990, 2, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, G.-J.; Gong, Z.-J.; Cheng, J.-A.; Zhu, Z.-R.; Mao, C.-G. Cloning and expression analysis of a G-protein α subunit-Gαo in the rice water weevil Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus Kuschel. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2011, 76, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Q.; Li, H.-C.; Yuan, G.-H.; Guo, X.-R.; Luo, M.-H. Gene cloning and expression analysis of G protein αq subunit from Helicoverpa assulta (Guenée). Agric. Sci. China 2008, 7, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Qin, Y. Cloning and expression analysis of G-protein Gαq subunit and Gβ1 subunit from Bemisia tabaci Gennadius (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2014, 87, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewen-Campen, B.; Jones, T.E.M.; Extavour, C.G. Evidence against a germ plasm in the milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus, a hemimetabolous insect. Biol. Open 2013, 2, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debolt, J.W. Meridic diet for rearing successive generations of Lygus hesperus. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1982, 75, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Patana, R. Disposable diet packet for feeding and oviposition of Lygus hesperus (Hemiptera: Miridae). J. Econ. Entomol. 1982, 75, 668–669. [Google Scholar]

- Brent, C.S.; Hull, J.J. Characterization of male-derived factors inhibiting female sexual receptivity in Lygus hesperus. J. Insect Physiol. 2014, 60, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strathmann, M.; Wilkie, T.M.; Simon, M.I. Diversity of the G-protein family: Sequences from five additional alpha subunits in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 7407–7409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, P.J.K.; Grigliatti, T.A. Diversity of G proteins in Lepidopteran cell lines: Partial sequences of six G protein alpha subunits. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2004, 57, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Wen, L.; Gao, X.; Jin, C.; Xue, Y.; Yao, X. CSS-Palm 2.0: An updated software for palmitoylation sites prediction. Protein Eng. Design Sel. 2008, 21, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: A multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinform. 2004, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucl. Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.T.; Taylor, W.R.; Thornton, J.M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1992, 8, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, S.M.; Hoveland, L.L.; Yarfitz, S.; Hurley, J.B. The Drosophila Go alpha-like G protein gene produces multiple transcripts and is expressed in the nervous system and in ovaries. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 18544–18551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ratnaparkhi, A.; Banerjee, S.; Hasan, G. Altered levels of Gq activity modulate axonal pathfinding in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 4499–4508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Graveley, B.R.; Brooks, A.N.; Carlson, J.W.; Duff, M.O.; Landolin, J.M.; Yang, L.; Artieri, C.G.; van Baren, M.J.; Boley, N.; Booth, B.W.; et al. The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 2011, 471, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, S.-H.; Dunham, J.P.; Carey, B.; Chang, P.L.; Li, F.; Edman, R.M.; Fjeldsted, C.; Scott, M.J.; Nuzhdin, S.V.; Tarone, A.M. A de novo transcriptome assembly of Lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae) with predicted alternative splices, single nucleotide polymorphisms and transcript expression estimates. Insect Mol. Biol. 2012, 21, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venables, J.P.; Tazi, J.; Juge, F. Regulated functional alternative splicing in Drosophila. Nucl. Acids Res. 2011, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, T.C.; Schmidt, C.J.; Neer, E.J. G-protein alpha o subunit: Mutation of conserved cysteines identifies a subunit contact surface and alters GDP affinity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 10295–10299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posner, B.A.; Mixon, M.B.; Wall, M.A.; Sprang, S.R.; Gilman, A.G. The A326S mutant of Gialpha1 as an approximation of the receptor-bound state. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 21752–21758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrari, Y.; Crouthamel, M.; Irannejad, R.; Wedegaertner, P.B. Assembly and trafficking of heterotrimeric G proteins. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 7665–7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, K.; Becker, A.; Sun, Y.; Hardy, R.; Zuker, C. Gq alpha protein function in vivo: Genetic dissection of its role in photoreceptor cell physiology. Neuron 1995, 15, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardie, R.C.; Martin, F.; Cochrane, G.W.; Juusola, M.; Georgiev, P.; Raghu, P. Molecular basis of amplification in Drosophila phototransduction: Roles for G protein, phospholipase C, and diacylglycerol kinase. Neuron 2002, 36, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunahara, R.K.; Taussig, R. Isoforms of mammalian adenylyl cyclase: Multiplicities of signaling. Mol. Interv. 2002, 2, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewavitharana, T.; Wedegaertner, P.B. Non-canonical signaling and localizations of heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabet, P.; Dumuis, A.; Sebben, M.; Pantaloni, C.; Bockaert, J.; Homburger, V. Immunocytochemical localization of the guanine nucleotide-binding protein Go in primary cultures of neuronal and glial cells. J. Neurosci. 1988, 8, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gabrion, J.; Brabet, P.; Nguyen Than Dao, B.; Homburger, V.; Dumuis, A.; Sebben, M.; Rouot, B.; Bockaert, J. Ultrastructural localization of the GTP-binding protein Go in neurons. Cell. Signal. 1989, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfgang, W.J.; Quan, F.; Goldsmith, P.; Unson, C.; Spiegel, A.; Forte, M. Immunolocalization of G protein alpha-subunits in the Drosophila CNS. J. Neuorsci. 1990, 10, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hull, J.J.; Wang, M. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of G Alpha Proteins from the Western Tarnished Plant Bug, Lygus hesperus. Insects 2015, 6, 54-76. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects6010054

Hull JJ, Wang M. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of G Alpha Proteins from the Western Tarnished Plant Bug, Lygus hesperus. Insects. 2015; 6(1):54-76. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects6010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleHull, J. Joe, and Meixian Wang. 2015. "Molecular Cloning and Characterization of G Alpha Proteins from the Western Tarnished Plant Bug, Lygus hesperus" Insects 6, no. 1: 54-76. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects6010054

APA StyleHull, J. J., & Wang, M. (2015). Molecular Cloning and Characterization of G Alpha Proteins from the Western Tarnished Plant Bug, Lygus hesperus. Insects, 6(1), 54-76. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects6010054