Colonization Priority of Spider Mites Modulates Antioxidant Defense of Bean Plants

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Plant Cultivation

2.1. Population Experiments

2.2. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

2.3. Data Analyzes

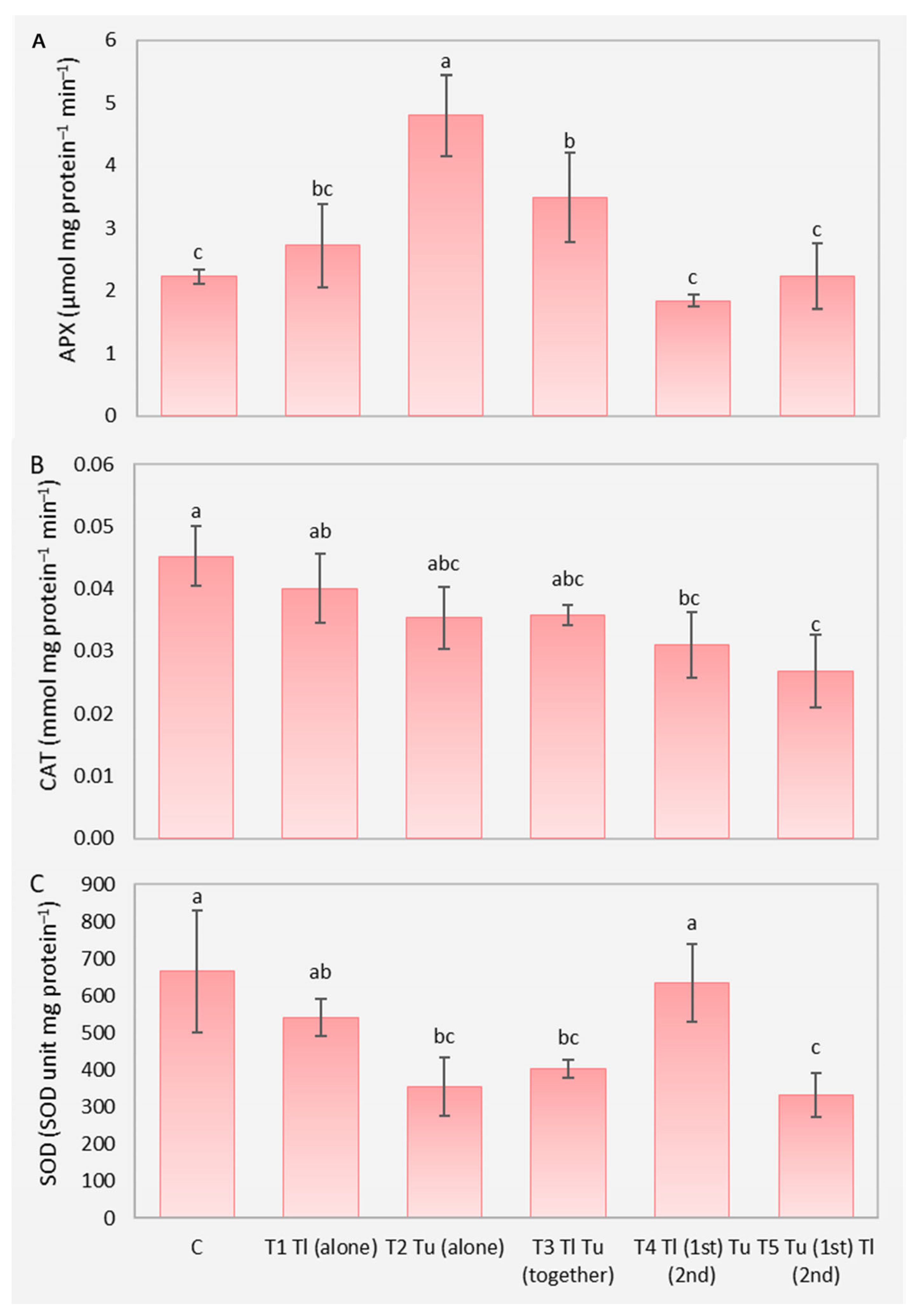

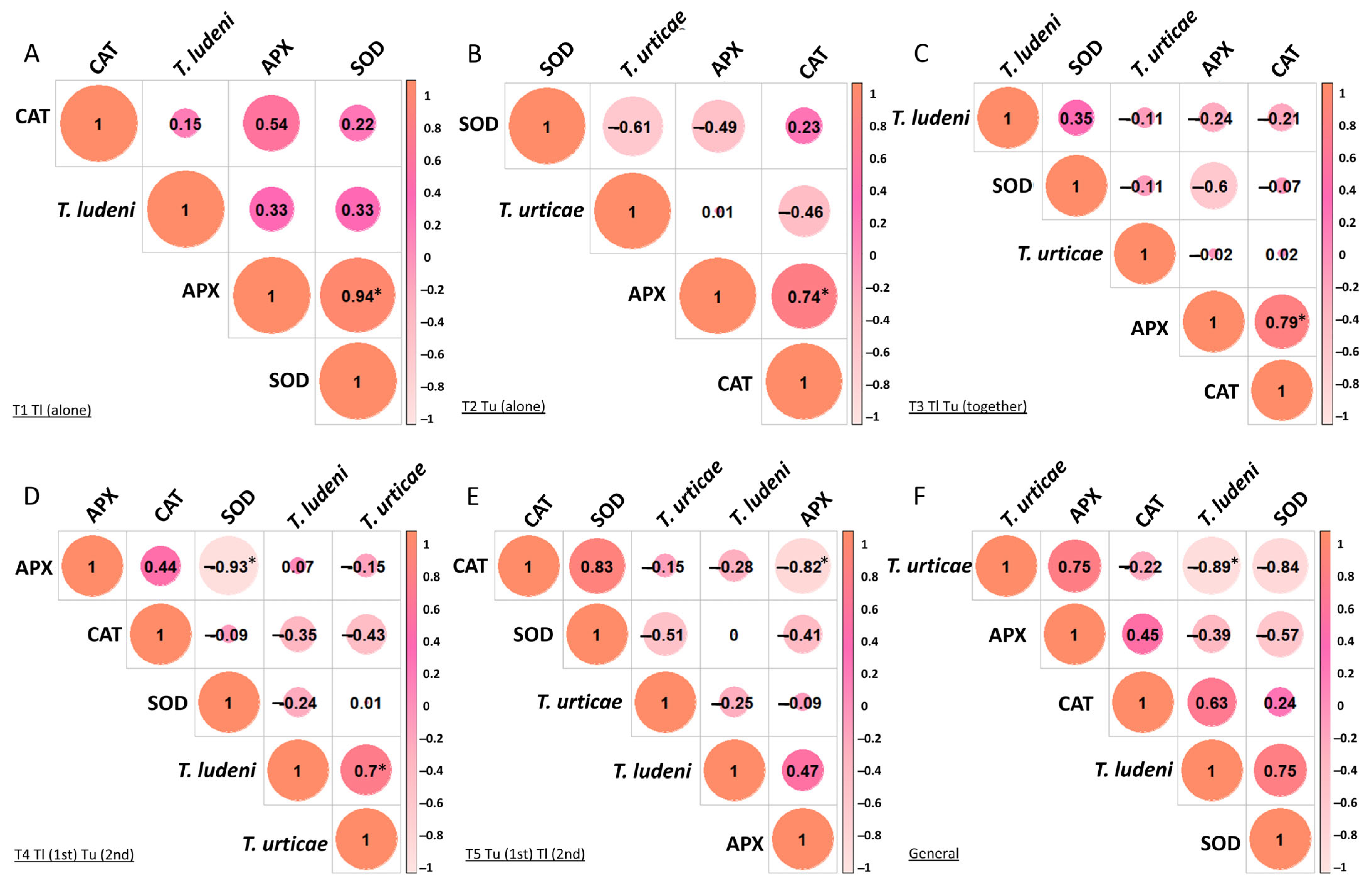

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chesson, P. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabás, G.; D’Andrea, R.; Stump, S.M. Chesson’s coexistence theory. Ecol. Monogr. 2018, 88, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaak, J.W.; De Laender, F. Intuitive and broadly applicable definitions of niche and fitness differences. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 23, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukami, T. Historical contingency in community assembly: Integrating niches, species pools, and priority effects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2015, 46, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, L.D.; Vanoverbeke, J.; Kilsdonk, L.J.; Urban, M.C. Evolving perspectives on monopolization and priority effects. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016, 31, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragata, I.; Costa-Pereira, R.; Kozak, M.; Majer, A.; Godoy, O.; Magalhaes, S. Specific sequence of arrival promotes coexistence via spatial niche pre-emption by the weak competitor. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 1629–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinho, D.P.; Janssen, A.; Dias, T.; Cruz, C.; Magalhães, S. Down-regulation of plant defence in a resident spider mite species and its effect upon con- and heterospecifics. Oecologia 2015, 180, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, D.P.; Janssen, A.; Li, D.; Cruz, C.; Magalhães, S. The distribution of herbivores between leaves matches their performance only in the absence of competitors. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 8405–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migeon, A.; Dorkeld, F. Spider Mites Web: A Comprehensive Database for the Tetranychidae. 2024. Available online: https://www1.montpellier.inrae.fr/CBGP/spmweb (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Reichert, M.B.; Silva, G.L.; Rocha, M.S.; Johann, L.; Ferla, N.J. Mite fauna (Acari) in soybean agroecosystem in the northwestern region of Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2014, 19, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, M.B.; Schneider, J.R.; Wurlitzer, W.B.; Ferla, N.J. Impacts of cultivar and management practices on the diversity and population dynamics of mites in soybean crops. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2024, 92, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, M.R.; Ament, K.; Sabelis, M.W.; Haring, M.A.; Schuurink, R.C. Differential timing of spider mite-induced direct and indirect defenses in tomato plants. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, M.R.; Sabelis, M.W.; Haring, M.A.; Schuurink, R.C. Intraspecific variation in a generalist herbivore accounts for differential induction and impact of host plant defences. Proc. R. Soc. B 2008, 275, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, R.A.; Lemos, F.; Bleeker, P.M.; Schuurink, R.C.; Pallini, A.; Oliveira, M.G.A.; Lima, E.R.; Kant, M.; Sabelis, M.W.; Janssen, A. A herbivore that manipulates plant defence. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurlitzer, W.B.; Schneider, J.R.; Silveira, J.A.G.; de Almeida Oliveira, M.G.; Ferla, N.J. Mite Infestation Induces a Moderate Oxidative Stress in Short-Term Soybean Exposure. Plants 2025, 14, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, E.F.; Pallini, A.; Janssen, A. Herbivores with similar feeding modes interact through the induction of different plant responses. Oecologia 2015, 180, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Redox sensing and signalling associated with reactive oxygen in chloroplasts, peroxisomes and mitochondria. Physiol. Plant. 2003, 119, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. ROS are good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, N.A.; Shafiq, F.; Ashraf, M. Ascorbic acid—A potential oxidant scavenger and its role in plant development and abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Fartyal, D.; Agarwal, A.; Shukla, T.; James, D.; Kaul, T.; Negi, Y.K.; Arora, S.; Reddy, M.K. Abiotic stress tolerance in plants: Myriad roles of ascorbate peroxidase. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. Novel insight into functions of ascorbate peroxidase in higher plants: More than a simple antioxidant enzyme. Redox Biol. 2023, 64, 1027789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, F.R.; Oliveira, J.T.A.; Martins-Miranda, A.S.; Viégas, R.A.; Silveira, J.A.G. Superoxide dismutase, catalase and peroxidase activities do not confer protection against oxidative damage in salt-stressed cowpea leaves. New Phytol. 2004, 163, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhamdi, A.; Noctor, G.; Baker, A. Plant catalases: Peroxisomal redox guardians. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 525, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Roychoudhury, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Anjum, N.A.; Gill, R.; Yadav, S.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M.; Mishra, P.; Sabat, S.C.; Tuteja, N. Superoxide Dismutase—Mentor of Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 10375–10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurlitzer, W.B.; Labudda, M.; Silveira, J.A.G.; Matthes, R.D.; Schneider, J.R.; Ferla, N.J. From signaling to stress: How does plant redox homeostasis behave under phytophagous mite infestation? Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 561–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Spinach chloroplasts scavenge hydrogen peroxide on illumination. Plant Cell Physiol. 1980, 21, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.D.; Prasad, T.K.; Stewart, C.R. Changes in isozyme profiles of catalase, peroxidase, and glutathione reductase during acclimation to chilling in mesocotyls of maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1995, 109, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakmak, I.; Marschner, H. Magnesium deficiency and high light intensity enhance activities of superoxide dismutase, ascorbate peroxidase, and glutathione reductase in bean leaves. Plant Physiol. 1992, 98, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Longo, O.T.; González, C.A.; Pastori, G.M.; Trippi, V.S. Antioxidant defenses under hyperoxygenic and hyperosmotic conditions in leaves of two lines of maize with differential sensitivity to drought. Plant Cell Physiol. 1993, 34, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutases I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolker, B. bbmle: Tools for General Maximum Likelihood Estimation. R Package Version 1.0.25.1. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=bbmle (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.john-fox.ca/Companion/downloads.html (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Lenth, R.V. Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 69, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihaka, R.; Gentleman, R. R: A language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 1996, 5, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargione, J.; Brown, C.S.; Tilman, D. Community assembly and invasion: An experimental test of neutral versus niche processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8916–8920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannette, R.L.; Fukami, T. Historical contingency in species interactions: Towards niche-based predictions. Ecol. Lett. 2014, 17, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delory, B.M.; Weidlich, E.W.A.; von Gillhaussen, P.; Temperton, V.M. When history matters: The overlooked role of priority effects in grassland overyielding. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 2369–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, T.N.; Letten, A.D.; Gilbert, B.; Fukami, T. Applying coexistence theory to priority effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 6205–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferragut, F.; Garzón-Luque, E.; Pekas, A. The invasive spider mite Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) alters community composition and host-plant use of native relatives. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2013, 60, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadini, M.A.; Oliveira, H.G.; Venzon, M.; Pallini, A.; Vilela, E.F. Distribuição espacial de ácaros fitófagos (Acari: Tetranychidae) em morangueiro. Neotrop. Entomol. 2007, 36, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foott, W.H. Competition between two species of mites. I. Experimental results. Can. Entomol. 1962, 94, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War, A.R.; Paulraj, M.G.; Ahmad, T.; Buhroo, A.A.; Hussain, B.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Sharma, H.C. Mechanisms of plant defense against insect herbivores. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1306–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandalios, J.G. Oxidative stress: Molecular perception and transduction of signals triggering antioxidant gene defenses. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2005, 38, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: Protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, V.C.; Tran, N.T.; Nguyen, D.S. The involvement of peroxidases in soybean seedlings’ defense against infestation of cowpea aphid. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2016, 10, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, M.E.; Arnaiz, A.; Velasco-Arroyo, B.; Grbic, V.; Diaz, I.; Martinez, M. Arabidopsis response to the spider mite Tetranychus urticae depends on the regulation of reactive oxygen species homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahtousi, S.; Talaee, L. The effect of spermine on Tetranychus urticae–Cucumis sativus interaction. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E. Comparison of catalase in diploid and haploid Rana rugosa using heat and chemical inactivation techniques. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 1997, 118, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Manchanda, G. ROS generation in plants: Boon or bane? Plant Biosyst. 2009, 143, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, S.; Osman, M.A. Alleviation of oxidative stress induced by spider mite invasion through application of elicitors in bean plants. Egypt. J. Biol. 2012, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, K.; Kot, I.; Górska-Drabik, E.; Jurado, I.G.; Kmieć, K.; Łagowska, B. Physiological response of basil plants to twospotted spider mite (Acari: Tetranychidae) infestation. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, K.; Jurado, I.G.; Kot, I.; Górska-Drabik, E.; Kmieć, K.; Łagowska, B.; Skwaryło-Bednarz, B.; Kopacki, M.; Jamiołkowska, A. Defense responses in the interactions between medicinal plants from Lamiaceae family and the two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Agronomy 2021, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworak, A.; Nykiel, M.; Walczak, B.; Miazek, A.; Szworst-Łupina, D.; Zagdańska, B.; Kiełkiewicz, M. Maize proteomic responses to separate or overlapping soil drought and two-spotted spider mite stresses. Planta 2016, 244, 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.Y.; Tian, S.S.; Liu, S.S.; Wang, W.Q.; Sui, N. Energy dissipation and antioxidant enzyme system protect photosystem II of sweet sorghum under drought stress. Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Tansley Review No. 112. Oxygen processing in photosynthesis: Regulation and signaling. New Phytol. 2000, 146, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, D.F.; Rodriguez, J.G.; Brown, G.C.; Luu, K.T.; Volden, C.S. Peroxidative responses of leaves in two soybean genotypes injured by twospotted spider mites (Acari: Tetranychidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 1986, 79, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Balfagón, D.; Arbona, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A. Modulation of antioxidant defense system is associated with combined drought and heat stress tolerance in citrus. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, K.R.; Bonifacio, A.; Martins, M.O.; Sousa, R.H.; Monteiro, M.V.; Silveira, J.A. Heat shock combined with salinity impairs photosynthesis but stimulates antioxidant defense in rice plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 225, 105851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. Abiotic stress, the field environment and stress combination. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittler, R.; Blumwald, E. Genetic engineering for modern agriculture: Challenges and perspectives. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, N.; Rivero, R.M.; Shulaev, V.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.; Irulappan, V.; Bagavathiannan, M.V.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Impact of combined abiotic and biotic stresses on plant growth and avenues for crop improvement by exploiting physio-morphological traits. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fixed Effects | Χ2 | DF | p-Value | |

| Treatments | 320.94 | 7 | <0.001 *** | |

| Foliar region | 2.79 | 1 | 0.09 | |

| Pairwise comparisons | Estimate | Std. error | z-value | p-value |

| T1 T. ludeni—T2 T. urticae | −0.050 | 0.07 | −0.70 | 0.484 |

| T1 T. ludeni—T3 T. ludeni | 0.802 | 0.10 | 8.34 | <0.001 |

| T1 T. ludeni—T4 T. ludeni | 0.384 | 0.08 | 4.73 | <0.001 |

| T1 T. ludeni—T5 T. ludeni | 3.078 | 0.25 | 12.51 | <0.001 |

| T3 T. ludeni—T4 T. ludeni | −0.418 | 0.10 | −4.03 | <0.001 |

| T3 T. ludeni—T5 T. ludeni | 2.276 | 0.25 | 8.93 | <0.001 |

| T4 T. ludeni—T5 T. ludeni | 2.694 | 0.25 | 10.80 | <0.001 |

| T2 T. urticae—T3 T. urticae | 0.187 | 0.08 | 2.40 | 0.020 |

| T2 T. urticae—T4 T. urticae | 1.006 | 0.10 | 10.18 | <0.001 |

| T2 T. urticae—T5 T. urticae | 0.319 | 0.08 | 4.03 | <0.001 |

| T3 T. urticae—T4 T. urticae | 0.820 | 0.10 | 7.96 | <0.001 |

| T3 T. urticae—T5 T. urticae | 0.132 | 0.08 | 1.57 | 0.131 |

| T4 T. urticae—T5 T. urticae | −0.688 | 0.10 | −6.62 | <0.001 |

| Random effect | Variance | Std. dev. | N | |

| Plants | 0.010 | 0.010 | 10 | |

| Leaves | 0.043 | 0.020 | 5 | |

| Model selection | AICc 1 | dAICc 2 | DF 3 | Weight 4 |

| GLMM negative binomial (selected) | 2465 | 0.0 | 12 | 1 |

| GLMM Poisson | 7436 | 4970 | 11 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Da-Costa, T.; Schneider, J.R.; Pavan, A.M.; Rodighero, L.F.; de Azevedo Meira, A.; Ferla, N.J.; Gonçalves Soares, G.L. Colonization Priority of Spider Mites Modulates Antioxidant Defense of Bean Plants. Insects 2026, 17, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020145

Da-Costa T, Schneider JR, Pavan AM, Rodighero LF, de Azevedo Meira A, Ferla NJ, Gonçalves Soares GL. Colonization Priority of Spider Mites Modulates Antioxidant Defense of Bean Plants. Insects. 2026; 17(2):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020145

Chicago/Turabian StyleDa-Costa, Tairis, Julia Renata Schneider, Aline Marjana Pavan, Luana Fabrina Rodighero, Anderson de Azevedo Meira, Noeli Juarez Ferla, and Geraldo Luiz Gonçalves Soares. 2026. "Colonization Priority of Spider Mites Modulates Antioxidant Defense of Bean Plants" Insects 17, no. 2: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020145

APA StyleDa-Costa, T., Schneider, J. R., Pavan, A. M., Rodighero, L. F., de Azevedo Meira, A., Ferla, N. J., & Gonçalves Soares, G. L. (2026). Colonization Priority of Spider Mites Modulates Antioxidant Defense of Bean Plants. Insects, 17(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020145