How Do Host Plants Mediate the Development and Reproduction of Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) When Fed on Tetranychus evansi or Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae)?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plants Material and Mite Colonies

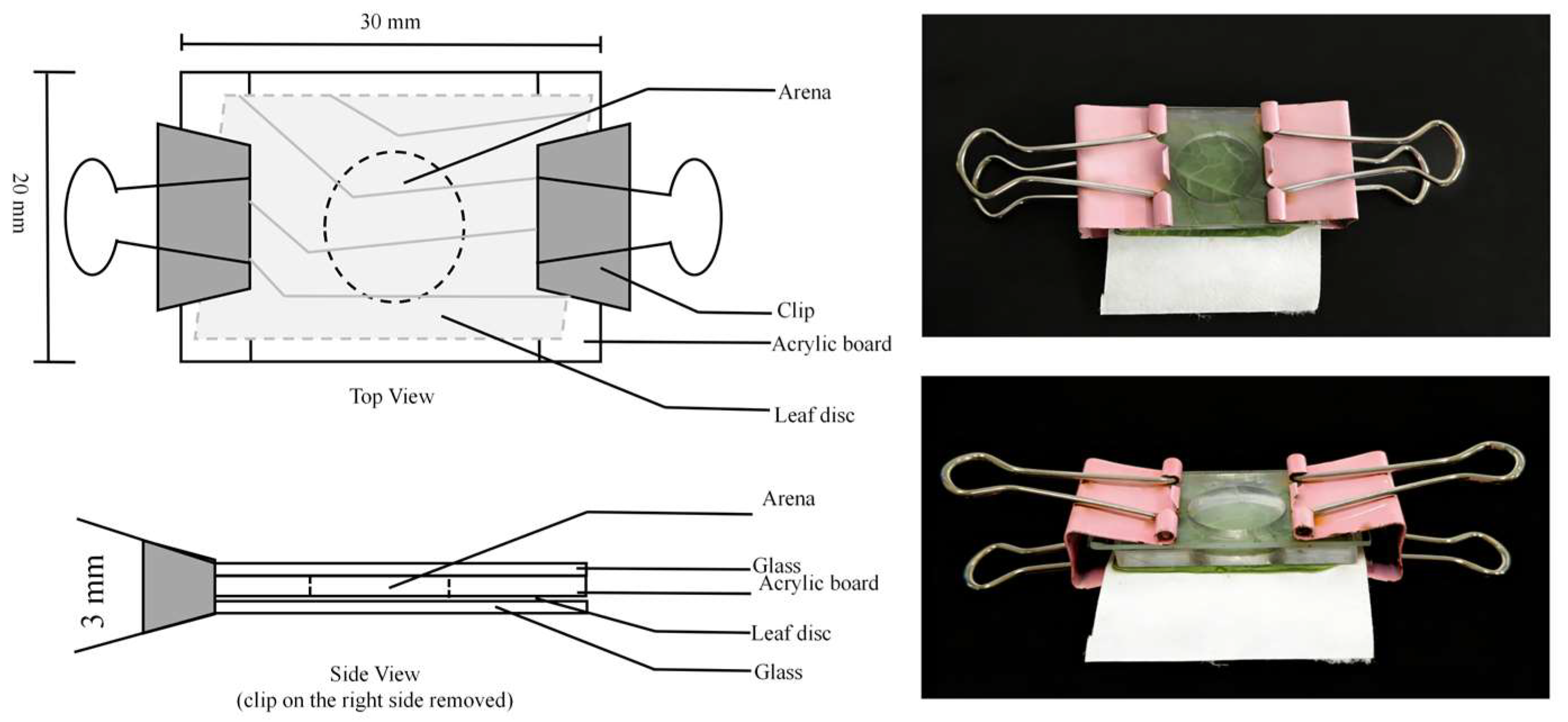

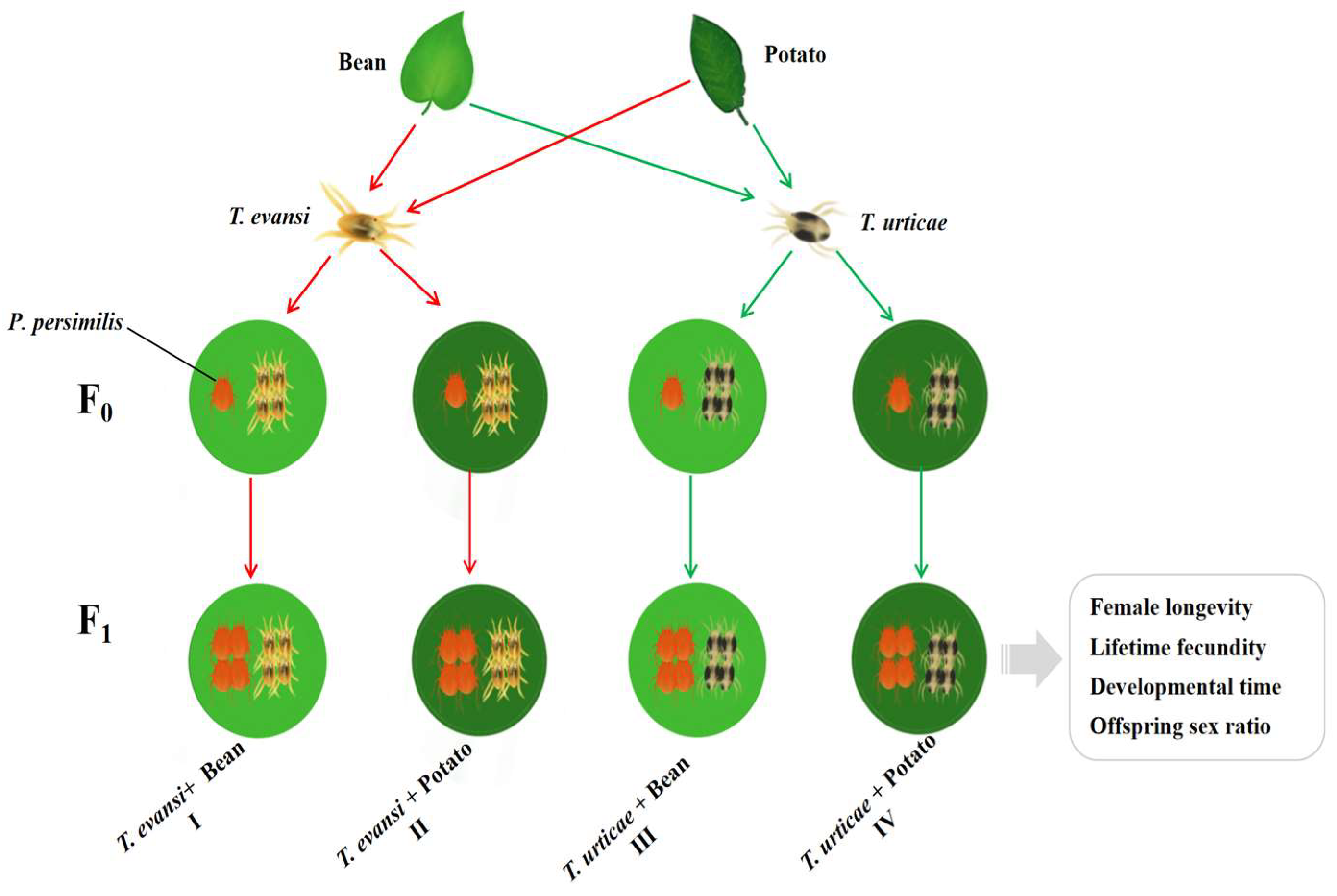

2.2. Experiment Set-Up

2.3. Life History Parameters and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

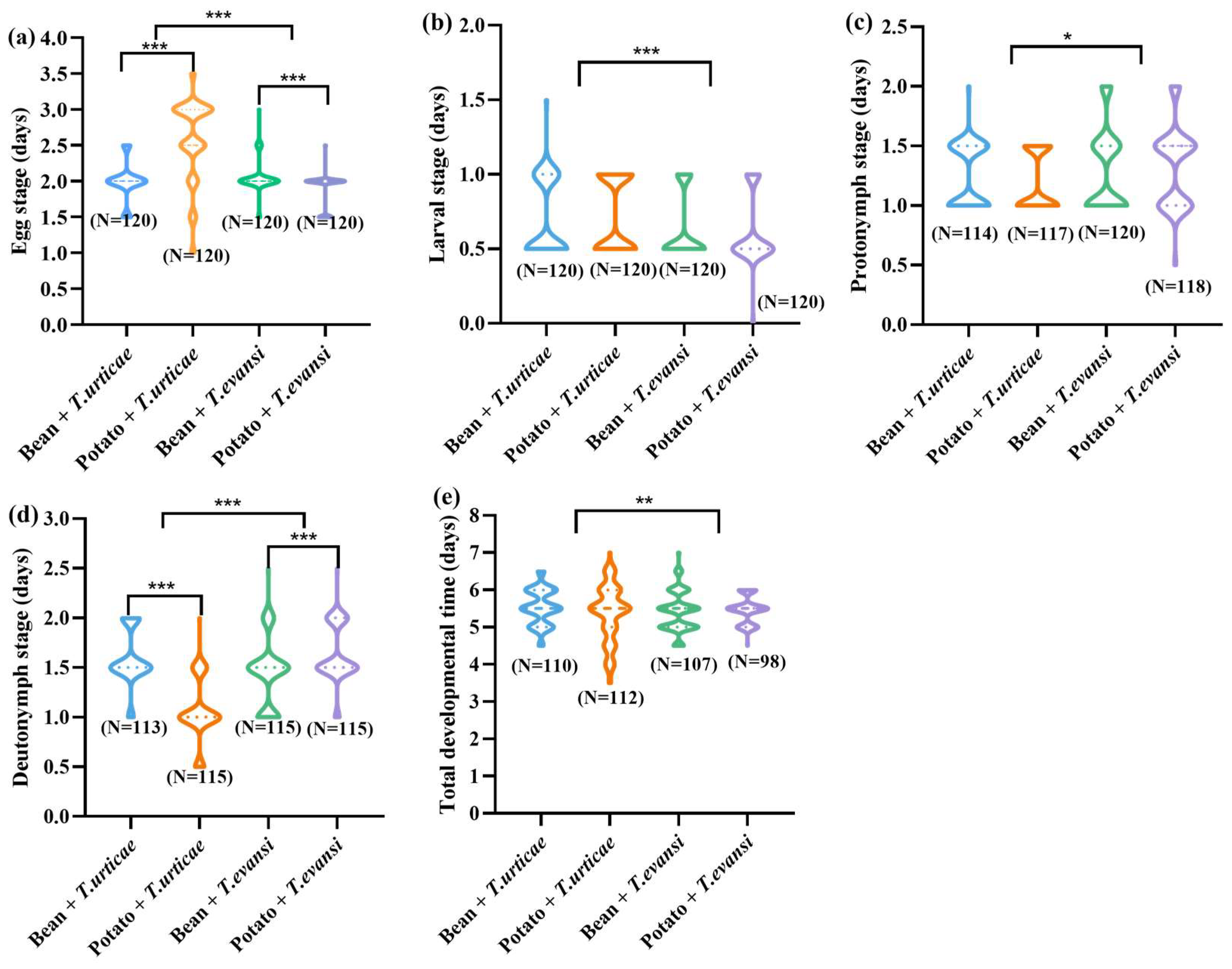

3.1. Influence of Host Plants on Immature Stages of P. persimilis Fed with T. urticae and T. evansi

3.2. Influence of Host Plants on Life Span of P. persimilis Fed with T. urticae and T. evansi

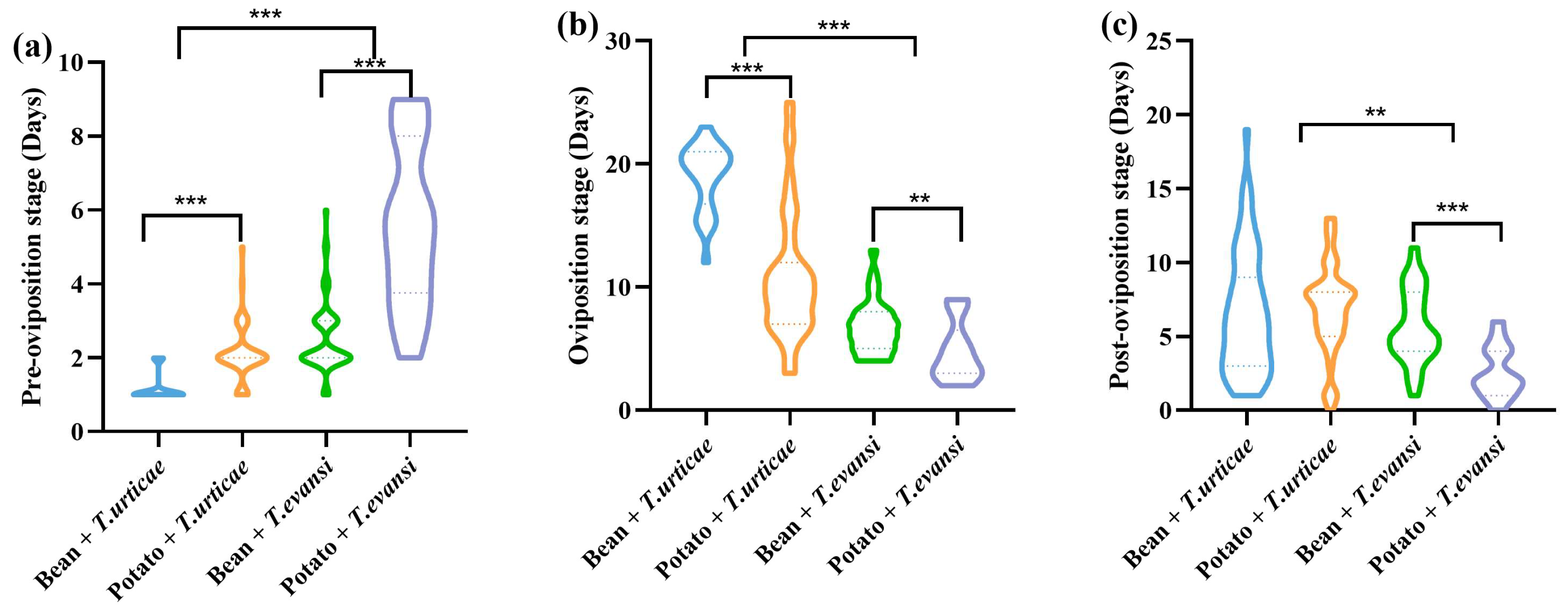

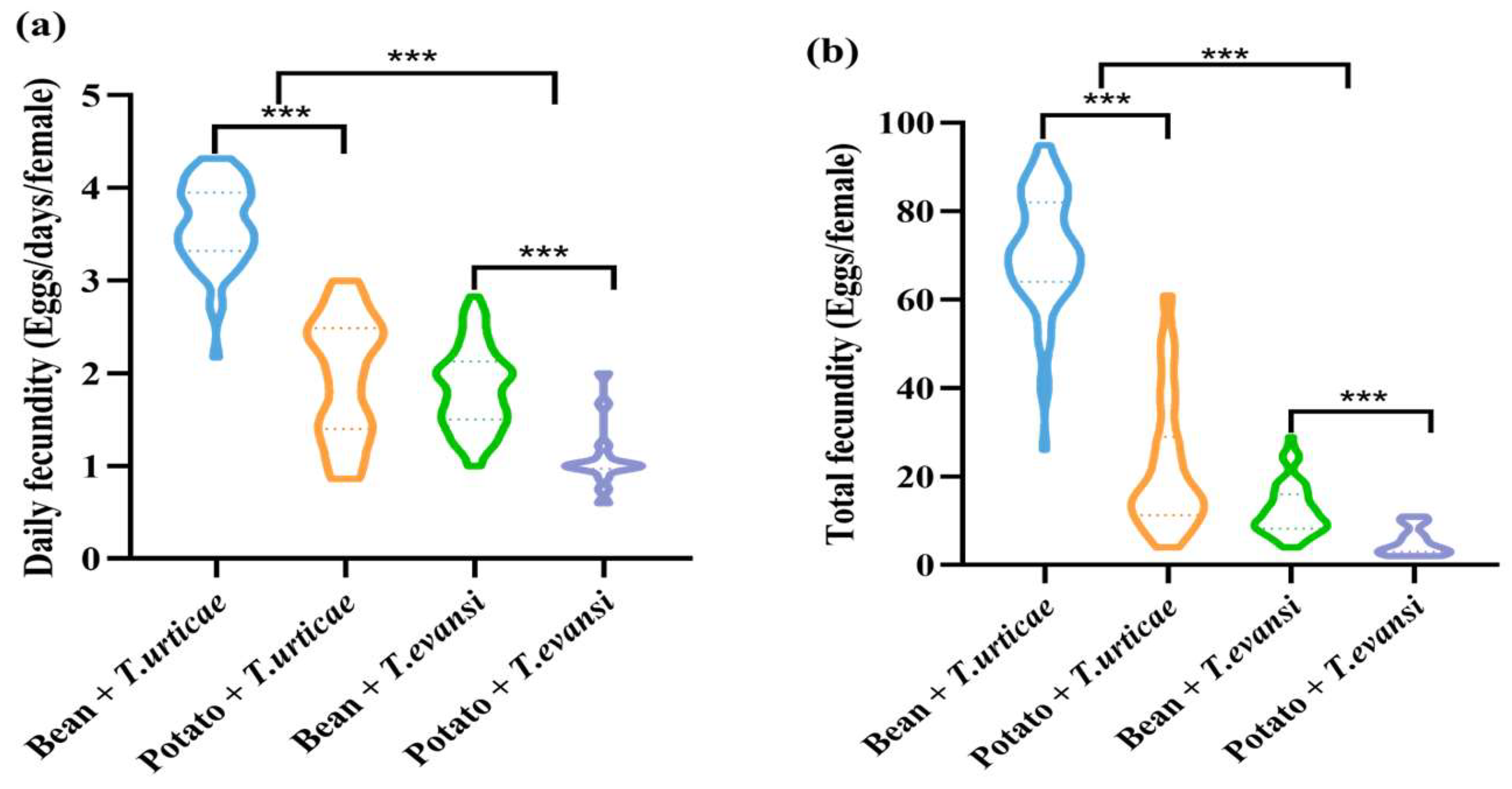

3.3. Influence of Host Plants on Fecundity of P. persimilis Fed with T. urticae and T. evansi

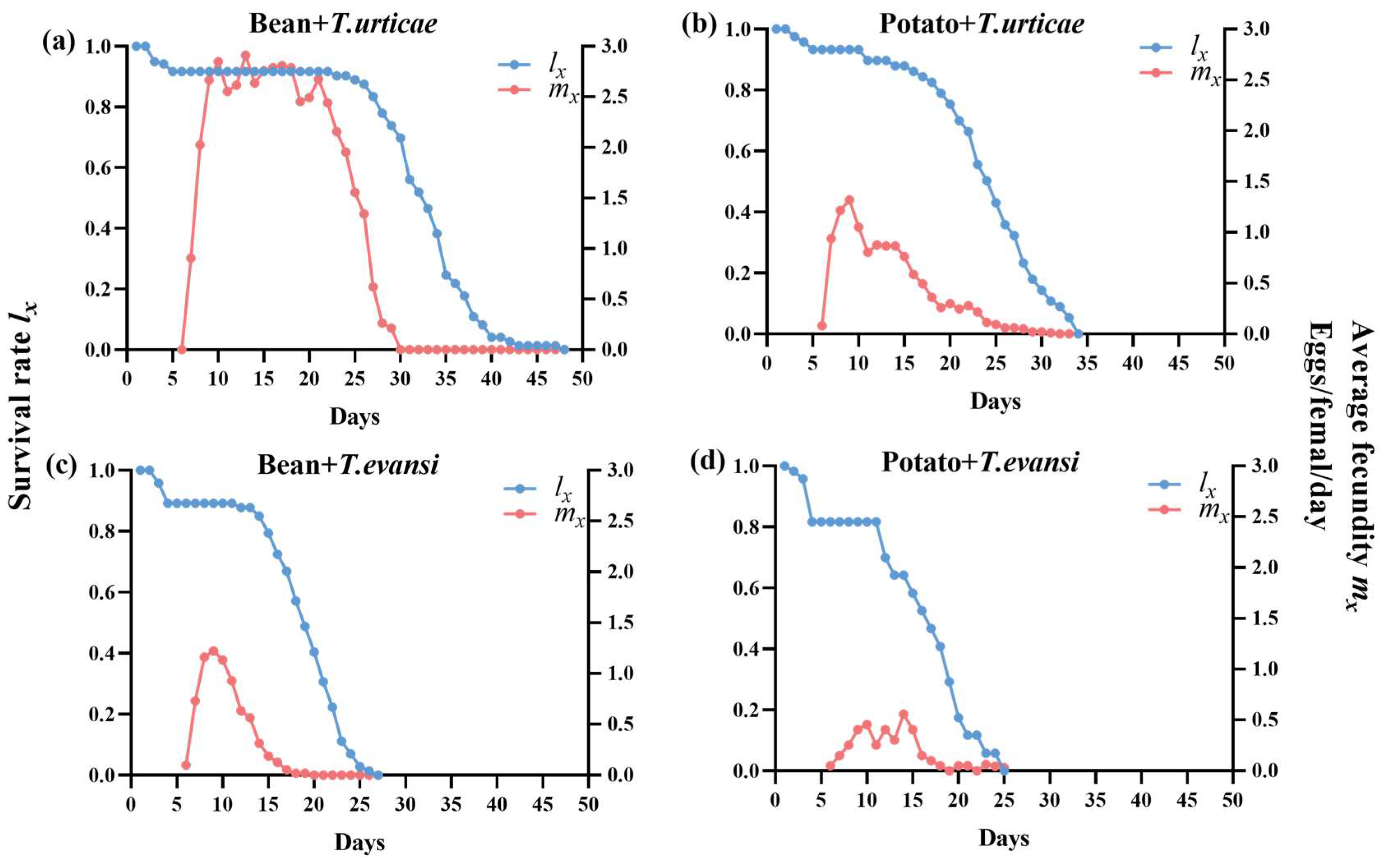

3.4. Survival Rate and Daily Female Fecundity of P. persimilis Fed with T. urticae and T. evansi

3.5. Life Table Parameters of P. persimilis Fed on T. urticae and T. evansi Reared on Two Different Host Plants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferragut, F.; Luque, E.G.; Pekas, A. The Invasive Spider Mite Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) Alters Community Composition and Host-Plant Use of Native Relatives. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2013, 60, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migeon, A.; Nouguier, E.; Dorkeld, F. Spider Mites Web: A Comprehensive Database for the Tetranychidae; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 557–560. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E.W.; Pritchard, A.E. The Tetranychoid Mites of Africa. Hilgardia 1960, 29, 455–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubou, A.; Migeon, A.; Roderick, G.K.; Navajas, M. Recent Emergence and Worldwide Spread of the Red Tomato Spider Mite, Tetranychus evansi: Genetic Variation and Multiple Cryptic Invasions. Biol. Invasions. 2011, 13, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Jin, P.Y.; Sun, C.P.; Hong, X.Y. First Distribution Record of the Tomato Red Spider Mite Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) in Mainland China. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2019, 24, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, T.; Vontas, J.; Tsagkarakou, A.; Dermauw, W.; Tirry, L. Acaricide Resistance Mechanisms in the Two-spotted Spider Mite Tetranychus urticae and other Important Acari: A review. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 40, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, J.; Desaki, Y.; Hata, K.; Uemura, T.; Yasuno, A.; Islam, M.; Maffei, M.E.; Ozawa, R.; Nakajima, T.; Galis, I.; et al. Tetranins: New Putative Spider Mite Elicitors of Host Plant Defense. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaratian, A.; Fathipour, Y.; Moharramipour, S. Comparative Life Table Analysis of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) on 14 Soybean Genotypes. Insect. Sci. 2011, 18, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P. Um novo acaro nocivo ao tomateiro na Bahia. Bol. Inst. Biol. Bahia 1954, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Moutia, L.A. Contribution to the study of some phytophagous Acarina and their predators in Mauritius. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1958, 49, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, B.W. Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (Acari: Tetranychidae); a New Pest of Tobacco in Zimbabwe; Coresta Phytopathology and Agronomy Study Group: Bergerac, France, 1983; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- de Moraes, G.J.; McMurtry, J.A. Comparison of Tetranychus evansi and T. urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) as Prey for Eight Species of Phytoseiid Mites. Entomophaga 1985, 30, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zheng, L.; Ye, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, C. Evaluation of the Predatory Mite Neoseiulus barkeri against Spider Mites Damaging Rubber Trees. Insects 2023, 14, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Lenteren, J.C. The State of Commercial Augmentative Biological Control: Plenty of Natural Enemies, but a Frustrating Lack of Uptake. BioControl 2012, 57, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opit, G.; Nechols, J.; Margolies, D. Biological Control of Twospotted Spider mites, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae), using Phytoseiulus persimilis Athias-Henriot (Acari: Phytoseidae) on Ivy Geranium: Assessment of Predator Release Ratios. Biol. Control 2004, 29, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opit, G.P. Comparing Chemical and Biological Control Strategies for Twospotted Spider Mites (Acari: Tetranychidae) in Commercial Greenhouse Production of Bedding Plants. J. Econ. Entomol. 2009, 102, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, G.J.; McMurtry, J.A. Suitability of the Spider Mite Tetranychus evansi as Prey for Phytoseiulus persimilis. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1986, 40, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grostal, R.; O’Dowd, D.J. Plants, Mites and Mutualism: Leaf Domatia and the Abundance and Reproduction of Mites on Viburnum tinus (Caprifoliaceae). Oecologia 1994, 97, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyari, H.; Fard, P.A.; Nozari, J. Effects of Host on Functional Response of Offspring in Two Populations of Trissolcus grandis, on the Sunn Pest. J. Appl. Entomol. 2004, 128, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, K.F.S.; Albuquerque, G.S.; Lima, J.O.G.D.; Pallini, A.; Molina-Rugama, A.J. Neoseiulus idaeus (Acari: Phytoseiidae) as a Potential Biocontrol Agent of the Two-spotted Spider Mite, Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) in Papaya: Performance on Different Prey Stage-host Plant Combinations. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2007, 41, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitenhuis, R.; Shipp, L.; Scott-Dupree, C.; Brommit, A.; Lee, W. Host Plant Effects on the Behaviour and Performance of Amblyseius swirskii (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2014, 62, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Lv, J.L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, B.M.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.N.; Wang, E.D. Prey Preference and Life Table of Amblyseius orientalis on Bemisia tabaci and Tetranychus cinnabarinus. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.M. Prey Switching in Rhyacophila dorsalis (Trichoptera) Alters with Larval Instar. Freshw. Biol. 2006, 51, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, N.; Thuy, N.T.; Quyen, H.L. Effects of Different Diets on Biological Characteristics of Predatory Mite Amblyseius eharai (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Insects 2023, 14, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.J.; Zhang, C.H.; Yi, Z.j.; Ran, X.C.; Zhang, L.S.; Liu, C.X.; Wang, M.Q.; Chen, H.Y. Effects of Three Prey Species on Development and Fecundity of the Predaceous Stinkbug Arma chinensis (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Chin. J. Bio Control 2016, 32, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Zhang, K.S.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.Q. Development and Reproduction of Four Predatory Mites (Parasitiformes: Phytoseiidae) Feeding on the Spider Mites Tetranychus evansi and T. urticae (Trombidiformes: Tetranychidae) and the Dried. Fruit Mite Carpoglyphus lactis (Sarcoptiformes: Carpoglyphidae). Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2024, 29, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.A. Leaf Structures Affect Predatory Mites (Acari: Phytoseiidae) and Biological Control: A Review. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2014, 62, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitenhuis, R.; Murphy, G.; Shipp, L.; Scott-Dupree, C. Amblyseius swirskii in Greenhouse Production Systems: A Floricultural Perspective. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2015, 65, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.N.; Guo, D.D.; Jiang, J.Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhang, J.P. Effects of Host Plant Species on the Development and Reproduction of Neoseiulus bicaudus (Phytoseiidae) Feeding on Tetranychus turkestani (Tetranychidae). Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2016, 21, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paspati, A.; Rambla, J.L.; López Gresa, M.P.; Arbona, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Granell, A.; González-Cabrera, J.; Urbaneja, A. Tomato Trichomes are Deadly Hurdles Limiting the Establishment of Amblyseius swirskii Athias-Henriot (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Biol. Control 2021, 157, 104572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomo, B.; Giannino, F.; Stéphanie, S.; Venturino, E. Effects of Limited Volatiles Release by Plants in Tritrophic Interactions. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2019, 16, 3331–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L. The Intrinsic Rate of Natural Increase of an Insect Population. J. Anim. Ecol. 1948, 17, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, I.P.; Toledo, S.; Moraes, G.J.; Kreiter, S.; Knapp, M. Search for Effective Natural Enemies of Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) in Northwest Argentina. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2007, 43, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmento, R.A.; Oliveira, H.G.; Holtz, A.M.; Da Silva, S.M.; Serrao, J.E.; Pallini, A. Fat Body Morphology of Eriopis connexa (Coleoptera, Coccinelidae) in Function of Two Alimentary Sources. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2004, 47, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.E.; Oliveira, C.L.; Sarmento, R.A.; Fadini, M.A.M.; Moreira, L.R. Biological Aspects of the Predator Cycloneda sanguinea (Linnaeus, 1763) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) Fed with Tetranychus evansi (Baker and Pritchard, 1960) (Acari: Tetranychidae) and Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas, 1878) (Homoptera: Aphididae) [Aspectos biologicos do predador Cycloneda sanguinea (Linnaeus, 1763) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) Alimentado com Tetranychus evansi (Baker e Pritchard, 1960) (Acari: Tetranychidae) e Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas, 1878) (Homoptera: Aphididae)]. Biosci. J. 2005, 21, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Navajas, M.; Moraes, G.J.; Auger, P.; Migeon, A. Review of the invasion of Tetranychus evansi: Biology, Colonization Pathways, Potential Expansion and Prospects for Biological Control. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2013, 59, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, G.J.; McMurtry, J.A. Chemically Mediated Arrestment of the Predaceous Mite Phytoseiulus persimilis by Extracts of Tetranychus evansi and Tetranychus urticae. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1985, 1, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, T.; Tsuchiya, A.; Kitashima, Y. Influence of Prey on Developmental Performance, Reproduction and Prey. Consumption of Neoseiulus californicus (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2006, 40, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, G.J.; McMurtry, J.A. Physiological Effect of the Host Plant on the Suitability of Tetranychus urticae as Prey for Phytoseiulus persimilis. Entomphaga 1987, 32, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, L.A.; Ferragut, F. Life-history of Predatory Mites Neoseiulus californicus and Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on Four Spider Mite Species as Prey, with Special Reference to Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae). Biol. Control 2005, 32, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geem, M.; Harvey, J.A.; Gols, R. Development of a Generalist Predator, Podisus maculiventris, on Glucosinolate Sequestering and Nonsequestering Prey. Naturwissenschaften 2014, 101, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, C.; Friberg, M. Enemy-free Space and Habitat-specific Host Specialization in a Butterfly. Occologia 2008, 157, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, F.; Wink, M. Mediation of Cardiac Glycoside Insensitivity in the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus): Role of an Amino Acid Substitution in the Ouabain Binding Site of Na+K+-ATPase. J. Chem. Ecol. 1996, 22, 1921–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordyce, J.A. The Lethal Plant Defence Paradox Remains: Inducible Host-plant Aristolochic Acids and The Growth and Defence of the Pipevine swallowtail. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2001, 100, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, B.; Schluttenhofer, C.; Wu, Y.M.; Pattanaik, S.; Yuan, L. Transcriptional regulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1829, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stages | Term | F Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg | P | F(1, 387) = 1.049 | 0.306 |

| S | F(1, 387) = 1.049 | 0.306 | |

| P × S | F(1, 387) = 82.679 | <0.001 *** | |

| Larval | P | F(1, 387) = 3.522 | 0.061 |

| S | F(1, 387) = 3.523 | 0.061 | |

| P × S | F(1, 387) = 8.112 | 0.005 ** | |

| Protonymph | P | F(1, 387) = 1.867 | 0.173 |

| S | F(1, 387) = 1.868 | 0.173 | |

| P × S | F(1, 387) = 11.358 | <0.001 *** | |

| Deutonymph | P | F(1, 387) = 0.487 | 0.485 |

| S | F(1, 387) = 0.488 | 0.485 | |

| P × S | F(1, 387) = 325.171 | <0.001 *** | |

| Total developmental time | P | F(1, 387) = 0.379 | 0.538 |

| S | F(1, 387) = 0.380 | 0.538 | |

| P × S | F(1, 387) = 3.478 | 0.063 | |

| Pre-oviposition period | P | F(1, 193) = 159.623 | <0.001 *** |

| S | F(1, 193) = 227.256 | <0.001 *** | |

| P × S | F(1, 193) = 45.897 | <0.001 *** | |

| Oviposition period | P | F(1, 193) = 92.111 | <0.001 *** |

| S | F(1, 193) = 284.56 | <0.001 *** | |

| P × S | F(1, 193) = 36.395 | <0.001 *** | |

| Post-oviposition period | P | F(1, 193) = 6.101 | 0.014 * |

| S | F(1, 193) = 21.965 | <0.001 *** | |

| P × S | F(1, 193) = 9.59 | 0.002 * | |

| Daily fecundity | P | F(1, 193) = 188.23 | <0.001 *** |

| S | F(1, 193) = 236.548 | <0.001 *** | |

| P × S | F(1, 193) = 26.896 | <0.001 *** | |

| Total fecundity | P | F(1, 193) = 199.332 | <0.001 *** |

| S | F(1, 193) = 361.16 | <0.001 *** | |

| P × S | F(1, 193) = 107.846 | <0.001 *** |

| Plants | Net Reproductive Rate (R0) | Mean Generation Time (T, Days) | Intrinsic Rate of Natural Increase (rm, Day−1) | Finite Rate of Increase λ | Doubling Time for Population (t, Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bean + T. urticae | 44.16 | 16.45 | 0.23 | 1.26 | 3.01 |

| Potato + T. urticae | 10.30 | 12.44 | 0.19 | 1.21 | 3.70 |

| Bean + T. evansi | 6.32 | 10.11 | 0.18 | 1.20 | 3.80 |

| Potato + T. evansi | 2.53 | 11.55 | 0.08 | 1.08 | 8.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Bi, S.; Huang, C.; Ran, L.; Yang, L.; Xiao, L.; Tan, Q.; Wang, E. How Do Host Plants Mediate the Development and Reproduction of Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) When Fed on Tetranychus evansi or Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae)? Insects 2026, 17, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020133

Zhang Y, Bi S, Huang C, Ran L, Yang L, Xiao L, Tan Q, Wang E. How Do Host Plants Mediate the Development and Reproduction of Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) When Fed on Tetranychus evansi or Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae)? Insects. 2026; 17(2):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020133

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yannan, Sijin Bi, Chuqin Huang, Li Ran, Li Yang, Lan Xiao, Qiumei Tan, and Endong Wang. 2026. "How Do Host Plants Mediate the Development and Reproduction of Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) When Fed on Tetranychus evansi or Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae)?" Insects 17, no. 2: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020133

APA StyleZhang, Y., Bi, S., Huang, C., Ran, L., Yang, L., Xiao, L., Tan, Q., & Wang, E. (2026). How Do Host Plants Mediate the Development and Reproduction of Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) When Fed on Tetranychus evansi or Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae)? Insects, 17(2), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020133