Application Method Determines Effects of Beauveria bassiana on Eucalyptus grandis Growth and Leaf-Cutting Ant Foraging

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Maintenance of Leaf-Cutting Ant Colonies

2.2. Fungus: Isolation and Molecular Characterization

2.3. Fungal Suspension

2.4. Treatment of Eucalyptus with Conidial Suspensions

2.5. Confirmation of the Endophytic Colonization in Eucalyptus

2.6. Biometric Parameters of Eucalyptus Treated with Conidial Suspension

2.7. Foraging Behavior Assessment

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

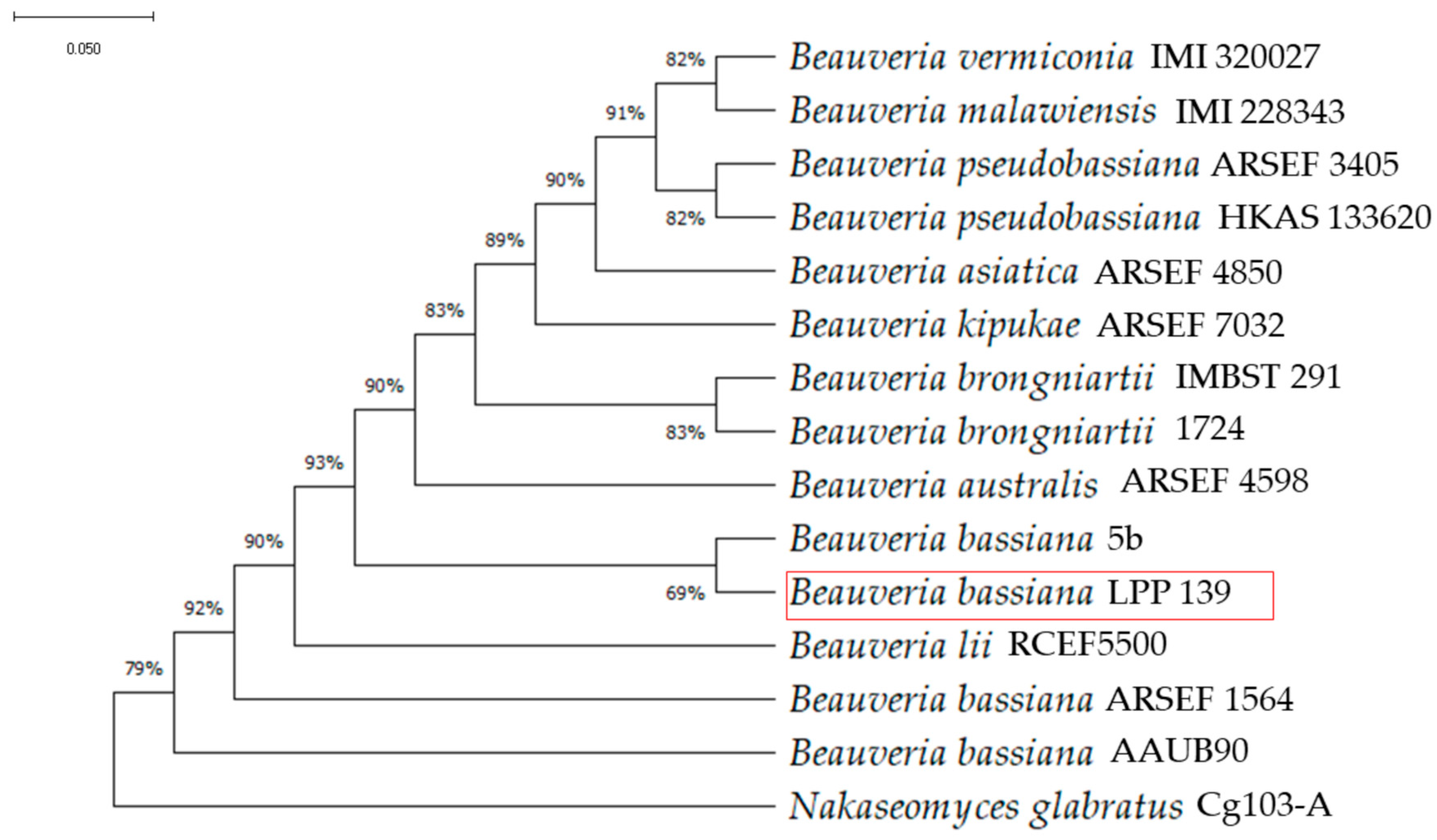

3.1. Beauveria Isolate Identification

3.2. Assessment of Endophytic Colonization

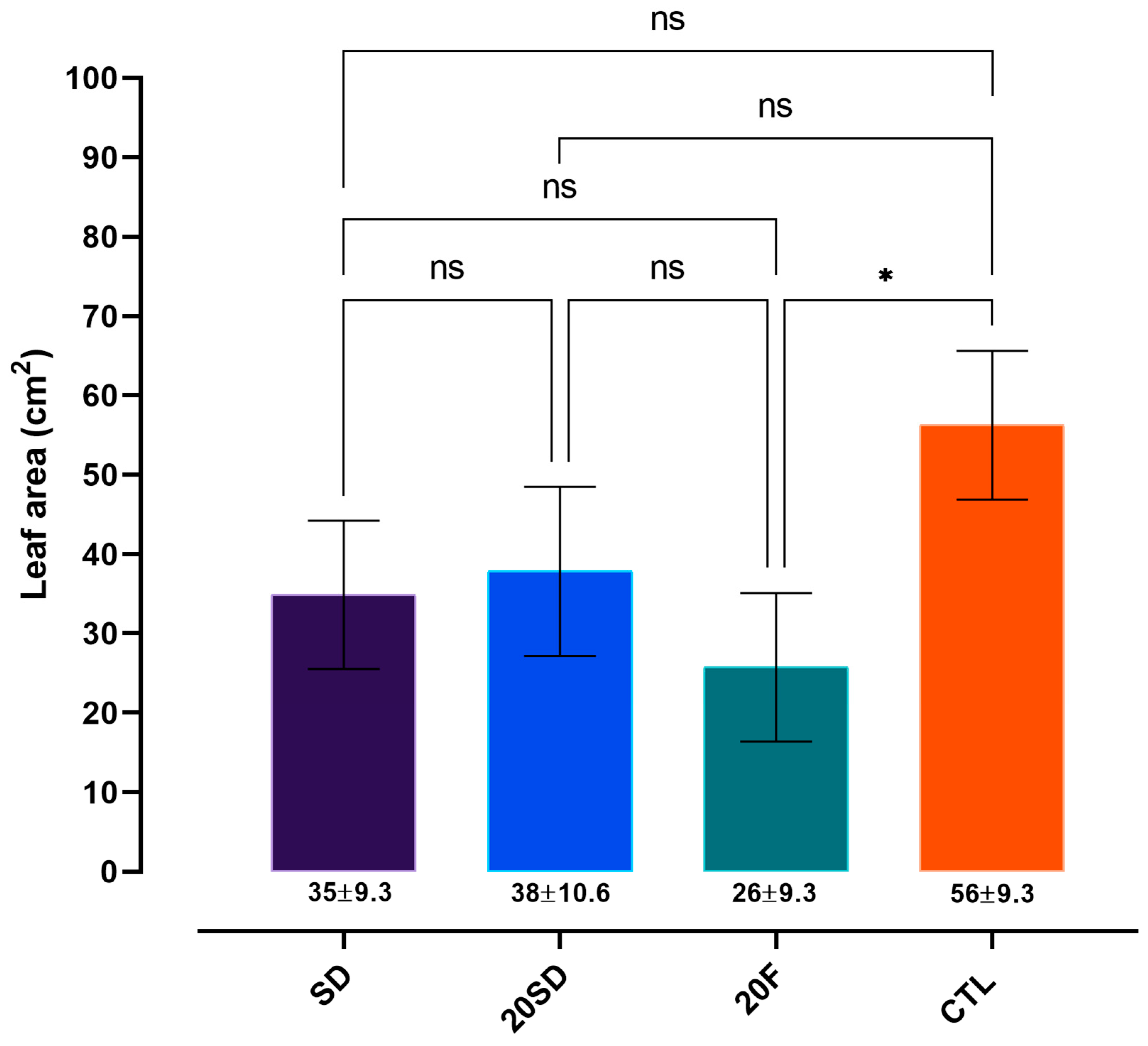

3.3. Plant Biometric Parameters

3.4. Ant Foraging Behavior

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPF | Entomopathogenic fungi |

| SD | Soil drenching at sowing |

| 20SD | Soil drenching 20 days after sowing |

| 20F | Foliar spraying 20 days after sowing |

| CTL | Non-inoculated control plants |

Appendix A

| Specie | GenBank Accession No. | Query Cover (%) | E-Value | Percent Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beauveria brongniartii strain IMBST 291 | FJ973055.1 | 90 | 0.0 | 97.58 |

| Beauveria brongniartii strain 1724 | FJ973056.1 | 90 | 0.0 | 97.58 |

| Beauveria vermiconia strain IMI 320027 | FJ973062.1 | 84 | 6 × 10−178 | 93.53 |

| Beauveria bassiana strain AAUB90 | MT588422.1 | 83 | 0.0 | 97.61 |

| Beauveria bassiana ARSEF 1564 | NR_111678.1 | 95 | 0.0 | 99.09 |

| Beauveria asiatica ARSEF 4850 | NR_111596.1 | 97 | 0.0 | 96.29 |

| Beauveria australis ARSEF 4598 | NR_111597.1 | 97 | 0.0 | 98.14 |

| Beauveria pseudobassiana ARSEF 3405 | NR_111598.1 | 97 | 0.0 | 97.22 |

| Beauveria kipukae ARSEF 7032 | NR_111600.1 | 97 | 0.0 | 97.67 |

| Beauveria lii strain RCEF5500 | NR_111678.1 | 97 | 0.0 | 97.91 |

| Beauveria malawiensis IMI 228343 | NR_136979.1 | 90 | 0.0 | 95.75 |

| Beauveria pseudobassiana strain HKAS 133620 | PV132939.1 | 89 | 0.0 | 97.26 |

| Beauveria bassiana isolate 5b | GQ379914.1 | 87 | 0.0 | 99.22 |

| Nakaseomyces glabratus voucher Cg103-A | KY981525.1 | 33 | 7 × 10−63 | 91.98 |

References

- Griffiths, T. Forests of Ash: An Environmental History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Sarre, A. Global Forest Resources Assessment, 2020: Main Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, J.; Turnbull, T.; Rennenberg, H.; Adams, M.A. Plasticity of leaf respiratory and photosynthetic traits in Eucalyptus grandis and E. regnans grown under variable light and nitrogen availability. Front. For. Glob. Change 2020, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBA-Indústria Brasileira de Árvores. Available online: https://www.iba.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/relatorio2024.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Lock, P.; Legg, P.; Whittle, L.; Black, S. Global Outlook for Wood Markets to 2030: Projections of Future Production, Consumption and Trade Balance; ABARES Report to Client Prepared for the Forest and Wood Products Australia; Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elli, E.F.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Bender, F.D. Impacts and uncertainties of climate change projections on Eucalyptus plantations productivity across Brazil. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 474, 118365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.F.; Machado, P.S.; Damacena, M.B.; Santos, S.A.; Guimarães, L.M.; Klopfenstein, N.B.; Alfenas, A.C. A new, highly aggressive race of Austropuccinia psidii infects a widely planted, myrtle rust-resistant, eucalypt genotype in Brazil. For. Pathol. 2021, 51, e12679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavigliasso, P.; González, E.; Scherf, A.; Villacide, J. Landscape configuration modulates the presence of leaf-cutting ants in eucalypt plantations. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickele, M.A.; Penteado, S.D.R.; de Queiroz, E.C. Artificial defoliation on Eucalyptus benthammii and Eucalyptus dunnii for simulation of leaf-cutting ant attacks. Floresta 2023, 53, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherf, A.; Corley, J.; Gioia, C.; Eskiviski, E.; Carazzo, C.; Patzer, H.; Dimarco, R. Impact of a leaf-cutting ant (Atta sexdens L.) on a Pinus taeda plantation: A 6 year-long study. J. Appl. Entomol. 2022, 146, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, U.G.; Kardish, M.R.; Ishak, H.D.; Wright, A.M.; Solomon, S.E.; Bruschi, S.M.; Carlson, A.L.; Bacci, M., Jr. Phylogenetic patterns of ant-fungus associations indicate that farming strategies, not only a superior fungal cultivar, explain the ecological success of leafcutter ants. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 2414–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Lucia, T.M.; Gandra, L.C.; Guedes, R.N. Managing leaf-cutting ants: Peculiarities, trends and challenges. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabattini, J.A.; Zanuncio, J.C.; Lemes, P.G. Chemical control of Acromyrmex lundi (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in anthropic ecosystems. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 3155–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, Y.; Barizon, R.R.M.; Kummrow, F.; Menezes-Sousa, D.; Assalin, M.R.; Rosa, M.A.; Almeida Pazianotto, R.A.; de Oliveira Lana, J.T. Environmental occurrence of perfluorooctanesulfonic acid from sulfluramid-based ant bait usage and its ecotoxicological risks. Environ. Res. 2025, 279, 121851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Sun, P.; Yin, C.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Ren, G.; Peng, L.; Wang, F. Distribution and potential health risks of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in water, sediment, and fish in Dongjiang River Basin, Southern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 99501–99510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Gao, Y.; Cui, L.; Wang, T.; Liang, Y.; Qu, G.; Yuan, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Jiang, G. Occurrence, temporal trends, and half-lives of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in occupational workers in China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente. National Implementation Plan Brazil: Convention Stockholm; MMA: Brasília, Brasil, 2015; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, R.R.S.; Teodoro, T.B.P.; Carolino, A.T.; Bitencourt, R.O.B.; Souza, W.G.; Boechat, M.S.B.; Sobrinho, R.R.; Silva, G.A.; Samuels, R.I. Production of Escovopsis conidia and the potential use of this parasitic fungus as a biological control agent of leaf-cutting ant fungus gardens. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffré, D.; Folgarait, P.J. Entomopathogenic Strains of the Fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum Damage the Fungus Cultivar of Pest Leaf-Cutter Ants. Neotrop. Entomol. 2023, 52, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teodoro, T.B.P.; Carolino, A.T.; Queiroz, R.R.S.; Oliveira, P.B.; Moreira, D.D.O.; Silva, G.A.; Samuels, R.I. Production of Escovopsis weberi (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) Mycelial Pellets and Their Effects on Leaf-Cutting Ant Fungal Gardens. Pathogens 2023, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folgarait, P.J.; Goffré, D.; Giraldo Osorio, A. Beauveria bassiana for the control of leafcutter ants: Strain and host differences. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgarait, P.J.; Goffré, D. Biological control of leaf-cutter ants using pathogenic fungi: Experimental laboratory and field studies. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2021, 169, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, N.; Szczepaniec, A. Endophytic entomopathogenic fungi as biological control agents of insect pests. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 6033–6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irsad; Shahid, M.; Haq, E.; Mohamed, A.; Rizvi, P.Q.; Kolanthasamy, E. Entomopathogen-based biopesticides: Insights into unraveling their potential in insect pest management. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1208237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, L.E.P.; Mota Filho, T.M.M.; Camargo, R.D.S.; Matos, C.A.O.; Forti, L.C. Effects of Entomopathogenic Fungi on Individuals as Well as Groups of Workers and Immatures of Atta sexdens rubropilosa Leaf-Cutting Ants. Insects 2020, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Giraldo, S.M.; Niño-Castro, A.; López-Peña, A.; Trejos-Vidal, D.; Correa-Bueno, O.; Montoya-Lerma, J. Immunity and survival response of Atta cephalotes (Hymenoptera: Myrmicinae) workers to Metarhizium anisopliae infection: Potential role of their associated microbiota. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Bidochka, M.J. The endophytic fungi Metarhizium, Pochonia, and Trichoderma, improve salt tolerance in hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Meng, Q.; Chen, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; Zou, Z. Evaluating Beauveria bassiana Strains for Insect Pest Control and Endophytic Colonization in Wheat. Insects 2025, 16, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulamtat, R.; El Fakhouri, K.; Jaber, H.; Oubayoucef, A.; Ramdani, C.; Fikraoui, N.; Al-Jaboobi, M.; El Fadil, M.; Maafa, I.; Mesfioui, A.; et al. Pathogenicity of entomopathogenic Beauveria bassiana strains on Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner). Front. Insect Sci. 2025, 5, 1552694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, S.; Karimi, J.; Cheniany, M.; Seifi, A.; Loverodge, J.; Butt, T.M. Endophytic entomopathogenic fungi enhance plant immune responses against tomato leafminer. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2025, 209, 108270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wei, T.; Lou, H.; Shu, X.; Chen, Q. A Critical Review on Communication Mechanism within Plant-Endophytic Fungi Interactions to Cope with Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Y.Y.; Ting, A.S.Y. Influence of fungal infection on plant tissues: FTIR detects compositional changes to plant cell walls. Fungal Ecol. 2019, 37, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranesi, M.; Vitale, S.; Staropoli, A.; Di Lelio, I.; Izzo, L.G.; De Luca, M.G.; Becchimanzi, A.; Pennacchio, F.; Lorito, M.; Woo, S.L.; et al. Field isolates of Beauveria bassiana exhibit biological heterogeneity in multitrophic interactions of agricultural importance. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 286, 127819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Guzmán, A.; Rey, M.D.; Froussart, E.; Quesada-Moraga, E. Elucidating the Effect of Endophytic Entomopathogenic Fungi on Bread Wheat Growth through Signaling of Immune Response-Related Hormones. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e00882-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macuphe, N.; Oguntibeju, O.O.; Nchu, F. Evaluating the Endophytic Activities of Beauveria bassiana on the Physiology, Growth, and Antioxidant Activities of Extracts of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Plants 2021, 10, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, H.G.; Della Lucia, T.M.C.; Moreira, D.D.O. Posição taxonomica das formigas cortadeiras. In As Formigas Cortadeiras, 1st ed.; Della Lucia, T.M.C., Ed.; Folha de Viçosa: Viçosa, Brasil, 1993; pp. 4–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Zermeño, M.A.; Gallou, A.; Berlanga-Padilla, A.M.; Serna-Domínguez, M.G.; Arredondo-Bernal, H.C.; Montesinos-Matías, R. Characterisation of entomopathogenic fungi used in the biological control programme of Diaphorina citri in Mexico. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 1192–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; Volume 18, pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Controle Microbiano de Insetos; Alves, S.B., Ed.; FEALQ: Piracicaba, Brasil, 1998; p. 1163. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, L.C.D.; Xavier, A.; Cruz, A.C.F.D.; Gallo, R.; Gatti, K.C.; Miranda, N.A.; Otoni, W.C. Effects of explant type, culture media and picloram and dicamba growth regulators on induction and proliferation of somatic embryos in Eucalyptus grandis x E. urophylla. Rev. Árvore 2017, 41, e410502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, S.; Ortiz, V.; Vega, F.E. Establishing fungal entomopathogens as endophytes: Towards endophytic biological control. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 74, 50360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, L.F.; Miranda, L.R.L.S.; Moraes, G.K.A.; Junior, A.F.C.; Chapla, V.M. Potencial biotecnológico de fungos endofiticos isolados de Clitoria gianensis. J. Biotechnol. Biodivers. 2024, 12, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, S.; Falconieri, G.S.; Bertini, L.; Pascale, A.; Bizzarri, E.; Morales-Sanfrutos, J.; Sabidó, E.; Ruocco, M.; Monti, M.M.; Russo, A.; et al. Beauveria bassiana rewires molecular mechanisms related to growth and defense in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 4225–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, C.; Tremmel, M.; Wirth, R. Do leaf cutting ants cut undetected? Testing the effect of ant-induced plant defences on foraging decisions in Atta colombica. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E.O. The Leafcutter Ants: Civilization by Instinct; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Aponte Rolon, B.; Arnold, A.E.; Sánchez Juliá, M.; Van Bael, S.A. Evaluating endophyte-rich leaves and leaf functional traits for protection of tropical trees against natural enemies. Funct. Ecol. 2025, 39, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Ju, Z.; Shi, H.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Zhou, W. Dual role of endophytic entomopathogenic fungi: Induce plant growth and control tomato leafminer Phthorimaea absoluta. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 4557–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khoury, C. Molecular insight into the endophytic growth of Beauveria bassiana within Phaseolus vulgaris in the presence or absence of Tetranychus urticae. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 2485–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Imran, Q.M.; Ahmed, M.B.; Falak, N.; Khatoon, A.; Yun, B.W. Endophyte-Mediated Stress Tolerance in Plants: A Sustainable Strategy to Enhance Resilience and Assist Crop Improvement. Cells 2022, 11, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, B.B.; López-Díaz, C.; Jiménez-Fernández, D.; Montes-Borrego, M.; Muñoz-Ledesma, F.J.; Ortiz-Urquiza, A.; Quesada-Moraga, E. In-planta detection and monitorization of endophytic colonization by a Beauveria bassiana strain using a new-developed nested and quantitative PCR-based assay and confocal laser scanning microscopy. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2013, 114, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyling, N.V. Methods for Isolation of Entomopathogenic Fungi from the Soil Environment; Laboratory Manual; Department of Ecology, Faculty of Life Science, University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Dinamarca, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, F.E. The use of fungal entomopathogens as endophytes in biological control: A review. Mycologia 2018, 110, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo Lopez, D.; Sword, G.A. The endophytic fungal entomopathogens Beauveria bassiana and Purpureocillium lilacinum enhance the growth of cultivated cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and negatively affect survival of the cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa zea). Biol. Control 2015, 89, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabaluk, J.T.; Ericsson, J.D. Metarhizium anisopliae seed treatment increases yield of field corn when applied for wireworm control. Agron. J. 2007, 99, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastías, D.A.; Gianoli, E.; Gundel, P.E. Fungal endophytes can eliminate the plant growth-defence trade-off. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Xia, W.; Cao, P.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhan, C.; Wang, N. Integrated Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Plant Hormones Jasmonic Acid and Salicylic Acid Coordinate Growth and Defense Responses upon Fungal Infection in Poplar. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra-Bucari, L.; González, M.G.; Iglesias, A.F.; Aguayo, G.S.; PeNalosa, M.G.; Vera, P.V. Beauvaria bassiana multifunction as an endophyte: Growth promotion and biologic of Trialeurodes vaporariorum, (Westwood) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in tomato. Insects 2020, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhao, X.; Huang, S.; Deng, J.; Li, X.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y. Pest management via endophytic colonization of tobacco seedlings by the insect fungal pathogen Beauveria bassiana. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 2007–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.S.; Montagu, K.D.; Conroy, J.P. Temperature effects on wood anatomy, wood density, photosynthesis and biomass partitioning of Eucalyptus grandis seedlings. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasso, M.; Hunt, M.; Jacobs, A.; O’Reilly-Wapstra, J. Characterisation of wood quality of Eucalyptus nitens plantations and predictive models of density and stiffness with site and tree characteristics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 491, 118992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekamawanti, H.A.; Simanjuntak, L.; Muin, A. Assessment of the Physical Quality of Eucalyptus pellita Seedlings from Shoot Cutting by Age Level. J. Sylva Lestari 2021, 9, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuepp, C.A.; Kratz, D.; Gabira, M.M.; Wendling, I. Survival and initial growth in the field of eucalyptus seedlings produced in different substrates. Pesq. Agropecu. Bras. 2020, 55, e01587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota Filho, T.M.M.; Camargo, R.D.S.; Stefanelli, L.E.P.; Zanuncio, J.C.; Dos Santos, A.; de Matos, C.A.O.; Forti, L.C. Allogrooming, Self-grooming, and Touching Behavior as a Mechanism to Disperse Insecticides Inside Colonies of a Leaf Cutting Ant. Neotrop. Entomol. 2022, 51, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.; Cable, R.N.; Mueller, U.G.; Bacci, M., Jr.; Pagnocca, F.C. Antagonistic interactions between garden yeasts and microfungal garden pathogens of leaf-cutting ants. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2009, 96, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Marín, H.; Zimmerman, J.K.; Rehner, S.A.; Wcislo, W.T. Active use of the metapleural glands by ants in controlling fungal infection. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2006, 273, 1689–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mas, N.; Gutiérrez-Sánchez, F.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Grandi, L.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Manuel Muñoz-Redondo, J.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M.; Quesada-Moraga, E. Endophytic Colonization by the Entomopathogenic Fungus Beauveria bassiana Affects Plant Volatile Emissions in the Presence or Absence of Chewing and Sap-Sucking Insects. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 660460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, P.; Howse, P.E.; Jackson, C.W. Control of the behaviour of leafcutting ants by their “symbiotic” fungus. Experientia 1996, 52, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saverschek, N.; Roces, F. Foraging leafcutter ants: Olfactory memory underlies delayed avoidance of plants unsuitable for the symbiotic fungus. Anim. Behav. 2011, 82, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falibene, A.; Roces, F.; Rössler, W. Long-term avoidance memory formation is associated with a transient increase in mushroom body synaptic complexes in leaf-cutting ants. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A.; Roces, F. Avoidance of plants unsuitable for the symbiotic fungus in leaf-cutting ants: Learning can take place entirely at the colony dump. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Queiroz, R.R.d.S.; Teodoro, T.B.P.; Carolino, A.T.; Bitencourt, R.d.O.B.; Samuels, R.I. Application Method Determines Effects of Beauveria bassiana on Eucalyptus grandis Growth and Leaf-Cutting Ant Foraging. Insects 2026, 17, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020134

Queiroz RRdS, Teodoro TBP, Carolino AT, Bitencourt RdOB, Samuels RI. Application Method Determines Effects of Beauveria bassiana on Eucalyptus grandis Growth and Leaf-Cutting Ant Foraging. Insects. 2026; 17(2):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020134

Chicago/Turabian StyleQueiroz, Raymyson Rhuryo de Sousa, Thais Berçot Pontes Teodoro, Aline Teixeira Carolino, Ricardo de Oliveira Barbosa Bitencourt, and Richard Ian Samuels. 2026. "Application Method Determines Effects of Beauveria bassiana on Eucalyptus grandis Growth and Leaf-Cutting Ant Foraging" Insects 17, no. 2: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020134

APA StyleQueiroz, R. R. d. S., Teodoro, T. B. P., Carolino, A. T., Bitencourt, R. d. O. B., & Samuels, R. I. (2026). Application Method Determines Effects of Beauveria bassiana on Eucalyptus grandis Growth and Leaf-Cutting Ant Foraging. Insects, 17(2), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17020134