Identification and Expression Analysis of the Cytochrome P450 Genes in Phyllotreta striolata and CYP6TH1/CYP6TH2 in the Involvement of Pyridaben Tolerance

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Rearing

2.2. Toxicological Bioassay

2.3. Sample Preparation for RNA-Seq

2.4. RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

2.5. Data Processing and Differential Expression Analysis

2.6. P450 Gene Identification, Phylogeny, and Expression Profiling

2.7. qRT-PCR Validation

2.8. RNA Interference and Toxicity Bioassay

2.9. Molecular Docking

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of CYP Genes

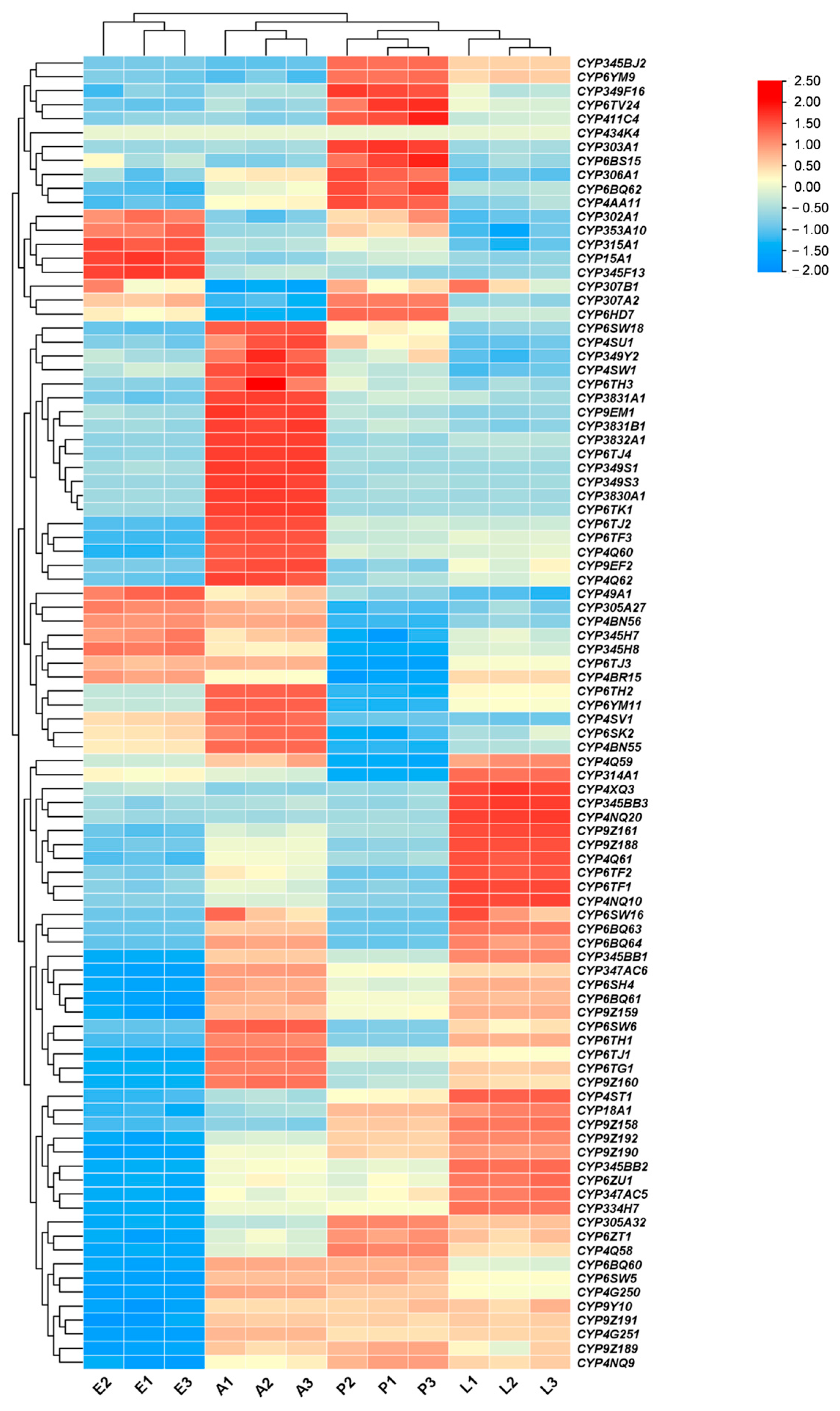

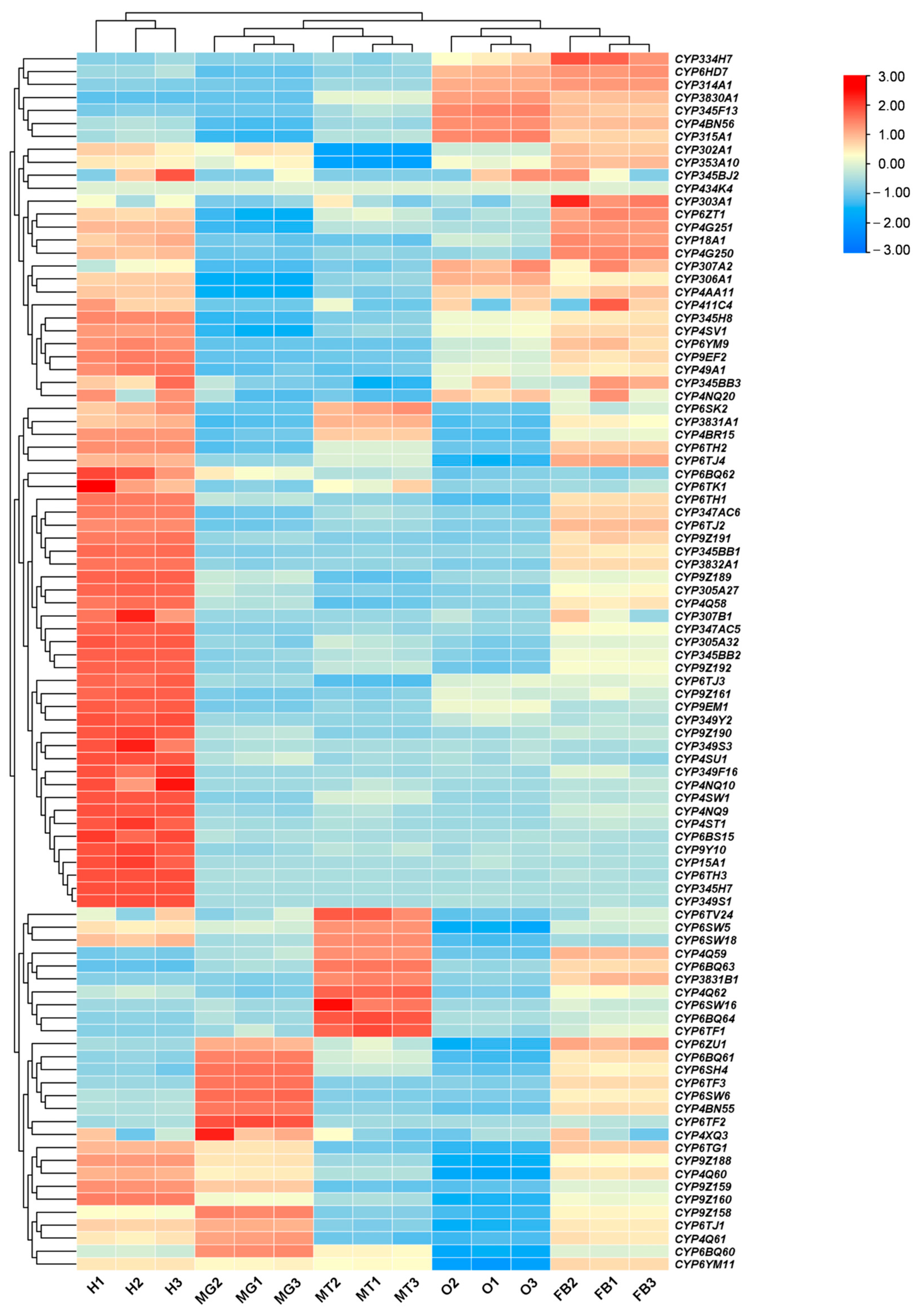

3.2. Tissue and Stage Expression Pattern

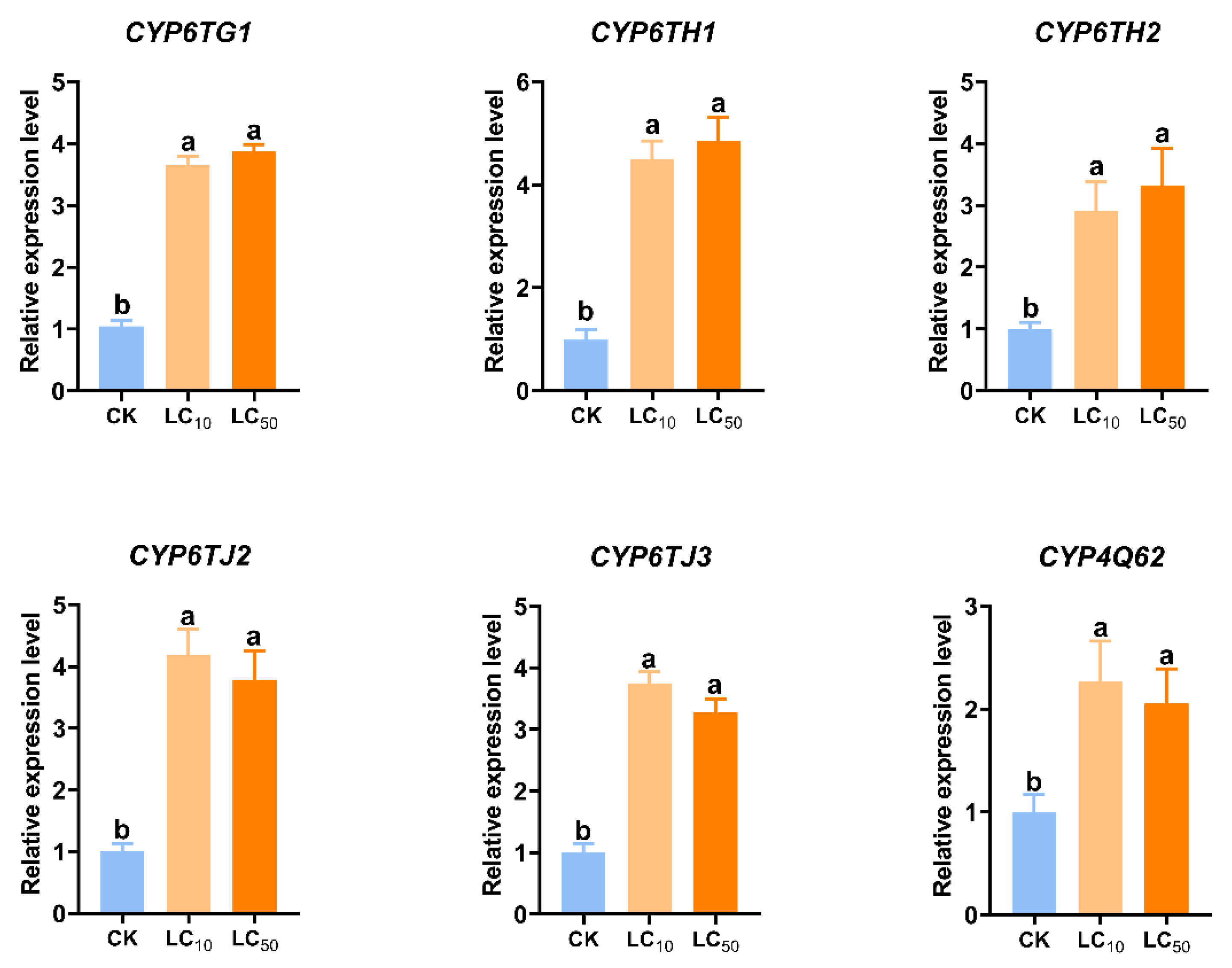

3.3. Impact of Pyridaben on Insect Survival and P450 Gene Expression

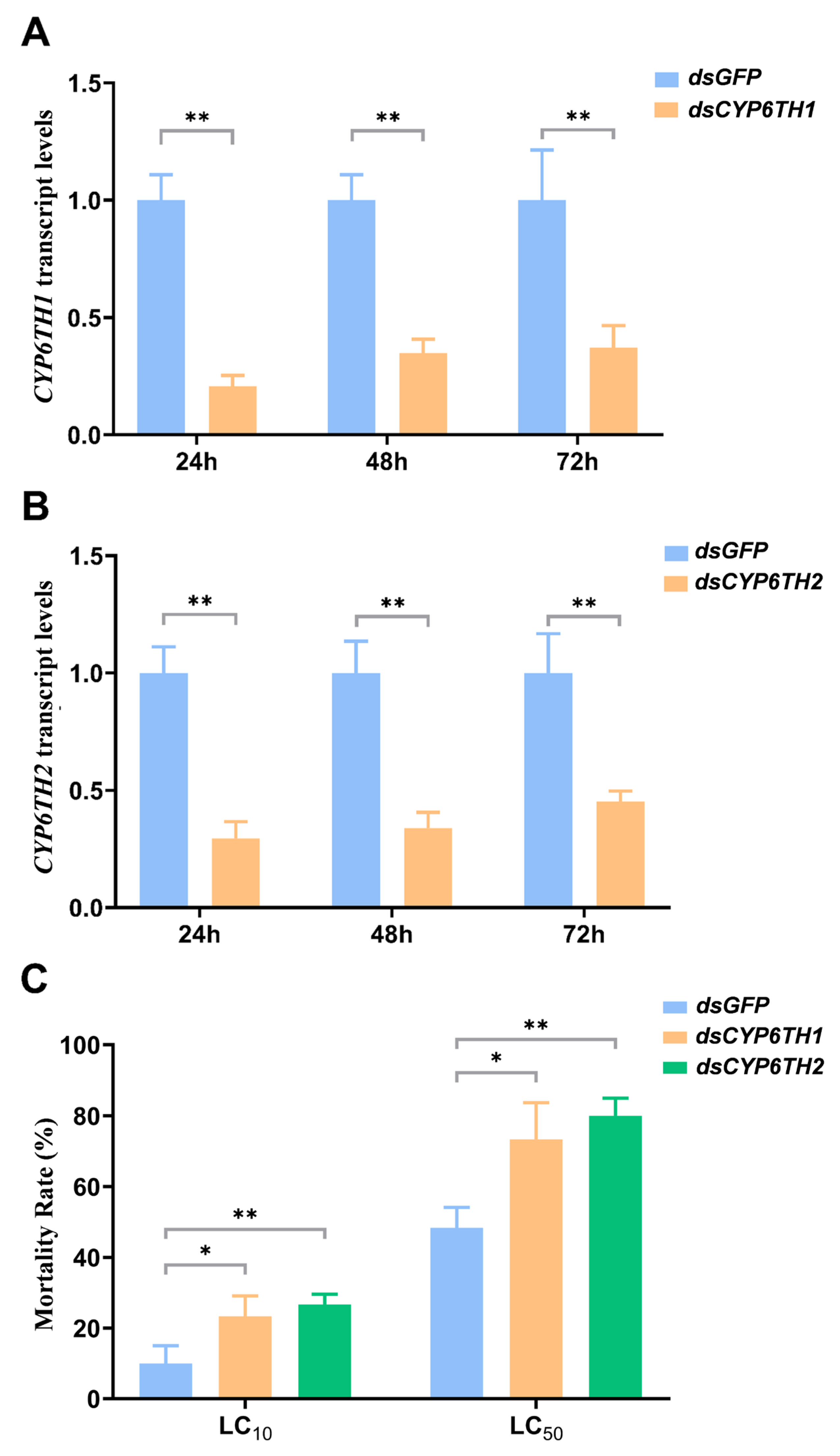

3.4. Knockdown of CYP6TH1 and CYP6TH2 Reduces Survival of P. striolata to Pyridaben Treatments

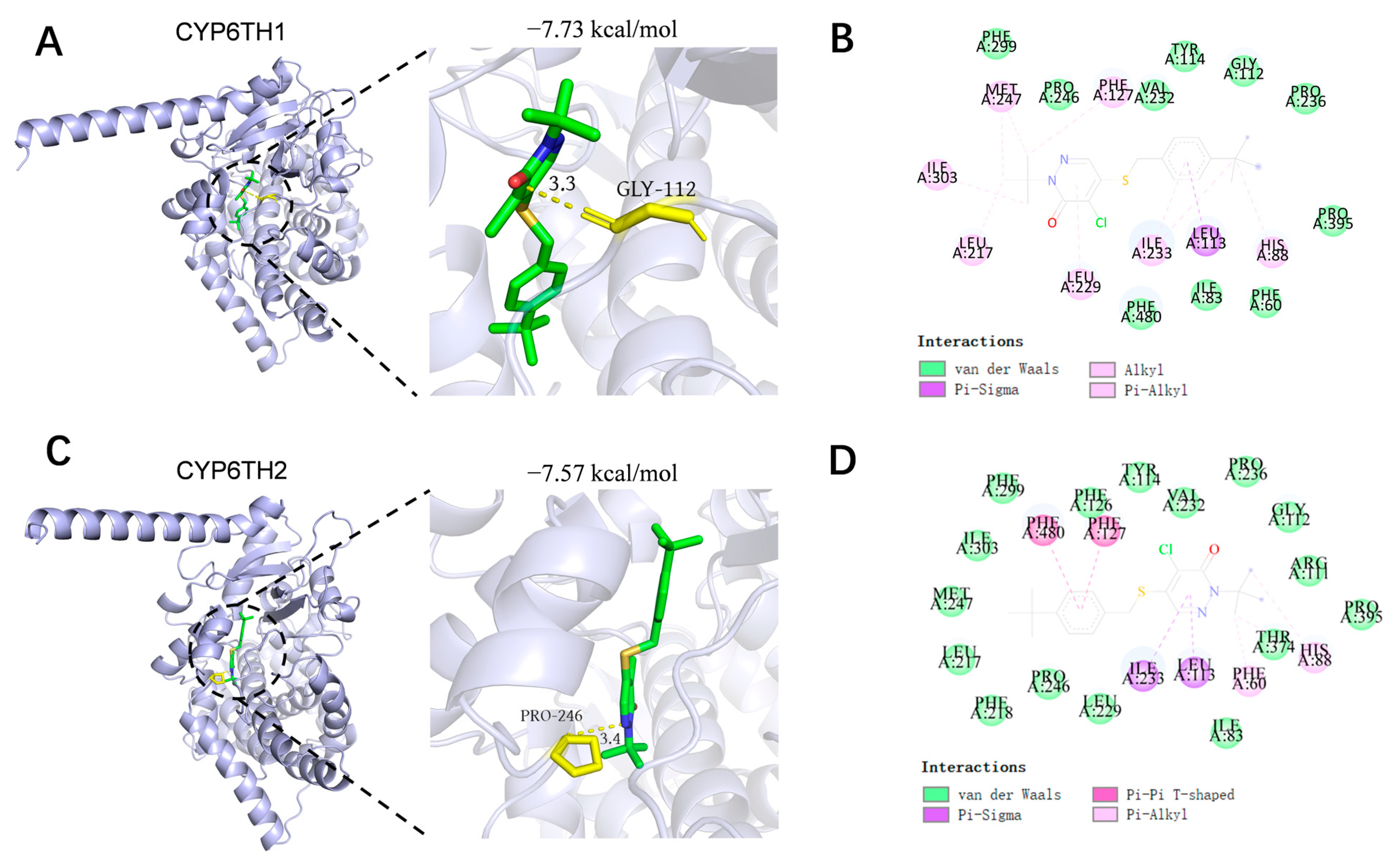

3.5. Predicted Binding of CYP6TH1 and CYP6TH2 with Pyridaben

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Costamagna, A.C.; Beran, F.; You, M. Biology, ecology, and management of flea beetles in Brassica Crops. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2024, 69, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengfei, X.; Nanda, S.; Fengliang, J.; Qingsheng, L.; Xia, F. Control efficiency and mechanism of spinetoram seed-pelleting against the striped flea beetle Phyllotreta striolata. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qiu, L.; Wang, H.; Fu, J. Chemicals used for controlling Phyllotreta striolata (F.). Fujian J. Agric. Sci. 2007, 1, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M.; Huang, D. Field Trials of Several Pesticides against Phyllotreta striolata. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2017, 13, 149–150. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.L.; Li, X.L.; Li, J.J.; Wang, X.M. Control effect of five pesticides against Rehamanniae flea beetle and their influence on natural enemies. Hunan Agric. Sci. 2008, 3, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, L.; Qiao, K.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, K. Toxicity of clothianidin and other insecticides to Phyllotreta striolata. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2015, 2, 230–234. [Google Scholar]

- Khalighi, M.; Dermauw, W.; Wybouw, N.; Bajda, S.; Osakabe, M.; Tirry, L.; Thomas, V.L. Molecular analysis of cyenopyrafen resistance in the two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 72, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Hu, J. Residue levels and risk assessment of acetamiprid–pyridaben mixtures in cabbage under various open field conditions. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2023, 37, e5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, S. Toxicity and field control efficacy of five insecticides against Phyllotreta striolata. Plant Prot. 2020, 46, 272–275. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, G.; Weng, Q. Screening of complex formulation against Phyllotreta spp. and effects in the field conditions. Agrochemicals 2019, 58, 759–762. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, H.; Choi, J.; Shin, E.; Kang, W.; Cho, S.; Kim, H.; Park, B.; Kim, G. Susceptibility to acaricides and the frequencies of point mutations in etoxazole-and pyridaben-resistant strains and field populations of the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae). Insects 2021, 12, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Xia, M.; Luo, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, C.; Yuan, G.; Wang, J.; Dou, W. Resistance of Panonychus citri (McGregor) (Acari: Tetranychidae) to pyridaben in China: Monitoring and fitness costs. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Ni, J.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Chai, J.; Xie, D.; Da, A.; Huang, P.; Li, S.; Ding, W. Acaricide resistance of Tetranychus cinnabarinus (Acari: Tetraychidae) from mulberry plantations in southwest China. Int. J. Acarol. 2013, 39, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Li, M.; Gong, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, T. Cytochrome P450s—Their expression, regulation, and role in insecticide resistance. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 120, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Hu, J.; Yang, J.; Yin, C.; Du, T.; Huang, M.; Fu, B.; Gong, P.; Liang, J.; Liu, S.; et al. Cytochrome P450 CYP6DB3 was involved in thiamethoxam and imidacloprid resistance in Bemisia tabaci Q (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 194, 105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, R.; Zhu, B.; Gao, X.; Liang, P. Overexpression of cytochrome P450 CYP6BG1 may contribute to chlorantraniliprole resistance in Plutella xylostella (L.). Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 74, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Xing, Z.; Dong, H.; Chen, X.; Ren, M.; Liu, K.; Rao, C.; Tan, A.; Su, J. Cytochrome P450 CYP6AE70 confers resistance to multiple insecticides in a Lepidopteran Pest, Spodoptera exigua. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 23141–23150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.B.; Niu, J.Z.; Yang, L.H.; Zhang, K.; Dou, W.; Wang, J.J. Transcription profiling of two cytochrome P450 genes potentially involved in acaricide metabolism in citrus red mite Panonychus citri. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2013, 106, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R. The cytochrome p450 homepage. Hum. Genome 2009, 4, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewitz, K.F.; O’Connor, M.B.; Gilbert, L.I. Molecular evolution of the insect Halloween family of cytochrome P450s: Phylogeny, gene organization and functional conservation. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 37, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolden, M.; Paine, M.J.I.; Nauen, R. Sequential phase I metabolism of pyrethroids by duplicated CYP6P9 variants results in the loss of the terminal benzene moiety and determines resistance in the malaria mosquito Anopheles funestus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2022, 148, 103813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Du, M.; Oreilly, A.O.; Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y. Single amino acid variations drive functional divergence of cytochrome P450s in Helicoverpa species. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2022, 146, 103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondji, C.S.; Hearn, J.; Irving, H.; Wondji, M.J.; Weedall, G. RNAseq-based gene expression profiling of the Anopheles funestus pyrethroid-resistant strain FUMOZ highlights the predominant role of the duplicated CYP6P9a/b cytochrome P450s. G3-Genes Genomes Genet. 2022, 12, jkab352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Zeng, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, M.; Shentu, X. Two critical detoxification enzyme genes, NlCYP301B1 and NlGSTm2 confer pymetrozine resistance in the brown planthopper (BPH), Nilaparvata lugens Stal. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 206, 106199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Yang, D.; Long, W.C.; Xiao, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, N.; Yang, Y. Genome-wide identification, molecular evolution and gene expression of P450 gene family in Cyrtotrachelus buqueti. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, P.; Zheng, H.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, D. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the Cytochrome P450 gene family in Bemisia tabaci MED and their roles in the insecticide resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shahzad, M.F.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Han, P.; Li, F.; Han, Z. Genome-wide analysis reveals the expansion of Cytochrome P450 genes associated with xenobiotic metabolism in rice striped stem borer, Chilo suppressalis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 443, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Li, G.Y.; Li, L.; Song, Q.S.; Stanley, D.; Wei, S.J.; Zhu, J.Y. Genome-wide and expression-profiling analyses of the cytochrome P450 genes in Tenebrionidea. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 111, e21954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh, K.; Nelson, D.R.; Ramirez, S.R. The Birth-and-Death Evolution of Cytochrome P450 Genes in Bees. Genome Biol. Evol. 2021, 13, evab261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.M.; Harpur, B.A.; Dogantzis, K.A.; Zayed, A.; Berenbaum, M.R. Genomic footprint of evolution of eusociality in bees: Floral food use and CYPome “blooms”. Insectes Soc. 2018, 65, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, R. Arthropod CYPomes illustrate the tempo and mode in P450 evolution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1814, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, Q.; Zhang, T.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Ma, E. Characteristics of Halloween genes and RNA interference-mediated functional analysis of LmCYP307a2 in Locusta migratoria. Insect Sci. 2022, 29, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hasnain, A.; Cheng, Q.; Xia, L.; Cai, Y.; Hu, R.; Gong, C.; Liu, X.; Pu, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Resistance monitoring and mechanism in the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) for chlorantraniliprole from Sichuan Province, China. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1180655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, B.; Tian, P.; Luo, C. Life-History Parameters of Phyllotreta striolata (F.) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Acquired by a Laboratory-Rearing Method. Insects 2025, 16, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, T.X.; Wang, D.F.; Ma, Y.P.; Zeng, L.L.; Meng, L.W.; Zhang, Q.; Dou, W.; Wang, J.J. Genome-wide and expression-profiling analyses of the cytochromeP450 genes in Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) and screening of candidate P450 genes associated with malathion resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 2932–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtof, M.; Lenaerts, C.; Cullen, D.; Vanden Broeck, J. Extracellular nutrient digestion and absorption in the insect gut. Cell Tissue Res. 2019, 377, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zou, X.; Zhang, N.; Feng, Q.; Zheng, S. Detoxification of insecticides, allechemicals and heavy metals by glutathione S-transferase SlGSTE1 in the gut of Spodoptera litura. Insect Sci. 2015, 22, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameku, T.; Yoshinari, Y.; Fukuda, R.; Niwa, R. Ovarian ecdysteroid biosynthesis and female germline stem cells. Fly 2017, 11, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauen, R.; Bass, C.; Feyereisen, R.; Vontas, J. The Role of Cytochrome P450s in Insect Toxicology and Resistance. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2022, 67, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, L. Regulation of CncC in insecticide-induced expression of cytochrome P450 CYP9A14 and CYP6AE11 in Helicoverpa armigera. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 197, 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Wang, W.; Deng, M.; Yang, Z.; Peng, H.; Huang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Lu, K. CYP321A Subfamily P450s Contribute to the Detoxification of Phytochemicals and Pyrethroids in Spodoptera litura. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 14989–15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Chen, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Sun, T.; Shen, Z. Identification of cytochrome P450 gene family and functional analysis of HgCYP33E1 from Heterodera glycines. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1219702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Du, S.; Liu, R.; Dai, W. Overexpression of Multiple Cytochrome P450 Genes Conferring Clothianidin Resistance in Bradysia odoriphaga. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 7636–7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Qiu, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, K.; Dai, W. Functional Characterization of CYP6QE1 and CYP6FV21 in Resistance to lambda-Cyhalothrin and Imidacloprid in Bradysia odoriphaga. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 2925–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.; Ma, E.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, K.Y.; Zhang, J. RNA interference of cytochrome P450 CYP6F subfamily genes affects susceptibility to different insecticides in Locusta migratoria. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 2154–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Gong, P.; Yin, C.; Yang, J.; Liu, S.; Fu, B.; Wei, X.; Liang, J.; Xue, H.; He, C.; et al. Cytochrome P450 CYP6EM1 confers resistance to thiamethoxam in the whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) via detoxification metabolism. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 208, 106272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Tang, J.; Gao, B.; Qu, C.; Wang, J.; Luo, C.; Wang, R. Overexpression of CYP6CX4 contributing to field-evolved resistance to flupyradifurone, one novel butenolide insecticide, in Bemisia tabaci from China. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 265, 131056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gong, C.; Pu, J.; Peng, A.; Yang, J.; Wang, X. Enhancement of Tolerance against Flonicamid in Solenopsis invicta Queens through Overexpression of CYP6AQ83. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Xie, X.; Hu, H.; Wu, J.; Ye, C.; Tang, R.; Wu, Z.; Shu, B. The chemosensory protein CSP4 increased dinotefuran tolerance in Diaphorina citri adults. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 213, 106503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Lu, K. Functional characterization of CYP6AE subfamily P450s associated with pyrethroid detoxification in Spodoptera litura. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 219, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Xiao, T.; Lu, K. Contribution of UDP-glycosyltransferases to chlorpyrifos resistance in Nilaparvata lugens. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 190, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Mai, W.; Pu, X.; Mo, H.; Shu, B.; Wu, Z. Identification and Expression Analysis of the Cytochrome P450 Genes in Phyllotreta striolata and CYP6TH1/CYP6TH2 in the Involvement of Pyridaben Tolerance. Insects 2026, 17, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010029

Zhu Y, Liu Z, Mai W, Pu X, Mo H, Shu B, Wu Z. Identification and Expression Analysis of the Cytochrome P450 Genes in Phyllotreta striolata and CYP6TH1/CYP6TH2 in the Involvement of Pyridaben Tolerance. Insects. 2026; 17(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yongqin, Zhongting Liu, Wenyong Mai, Xinhua Pu, Haoyue Mo, Benshui Shu, and Zhongzhen Wu. 2026. "Identification and Expression Analysis of the Cytochrome P450 Genes in Phyllotreta striolata and CYP6TH1/CYP6TH2 in the Involvement of Pyridaben Tolerance" Insects 17, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010029

APA StyleZhu, Y., Liu, Z., Mai, W., Pu, X., Mo, H., Shu, B., & Wu, Z. (2026). Identification and Expression Analysis of the Cytochrome P450 Genes in Phyllotreta striolata and CYP6TH1/CYP6TH2 in the Involvement of Pyridaben Tolerance. Insects, 17(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010029