Unlocking the Potential of Bacillus Strains for a Two-Front Attack on Wireworms and Fungal Pathogens in Oat

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

2.2. Plant Growth Promoting Traits of Bacteria and AMPs Gene Detection

2.3. Insecticidal Potential

2.4. Antifungal Potential

2.5. Molecular Identification of Potentially Effective Isolates

2.6. Pot Experiments

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

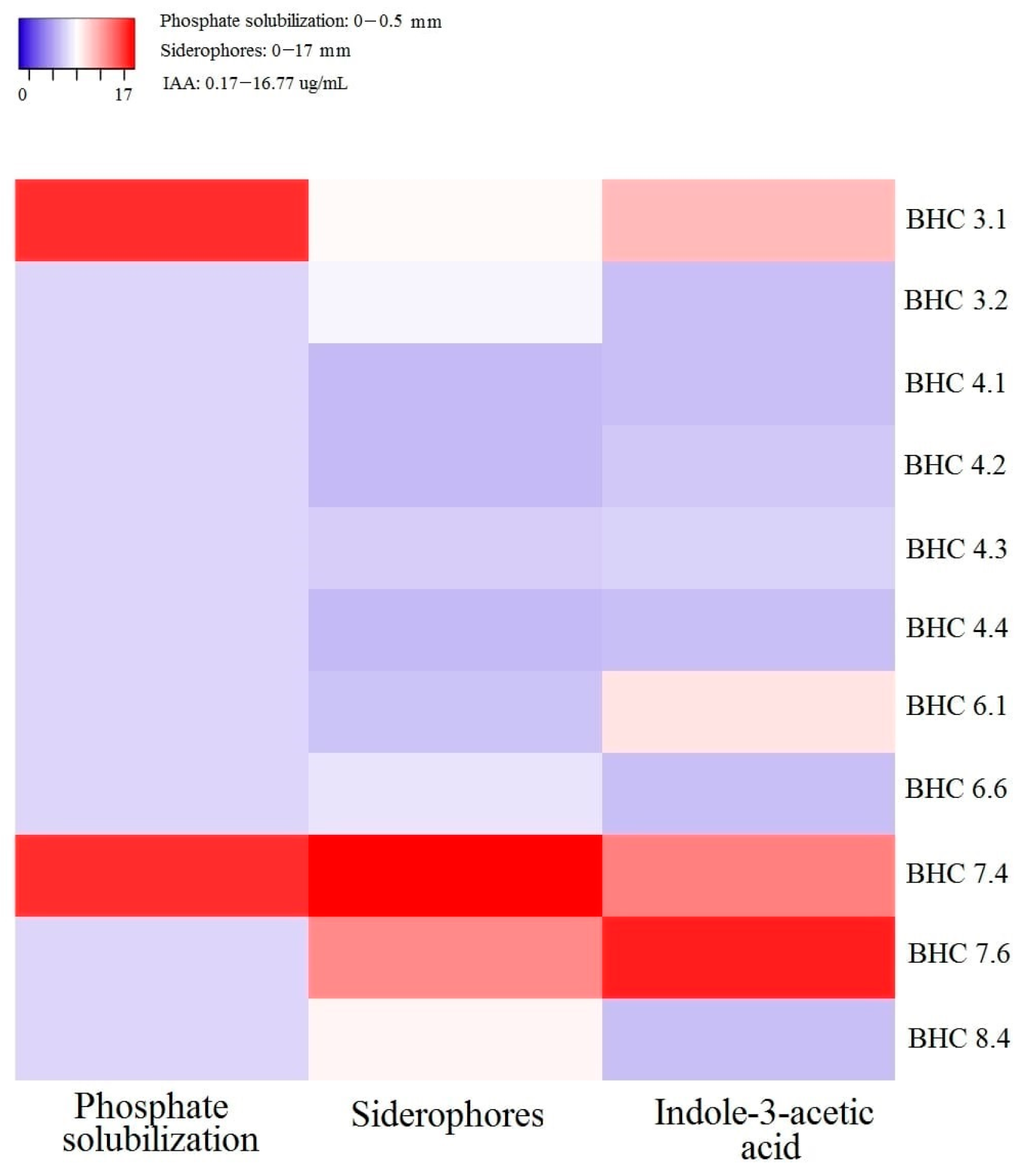

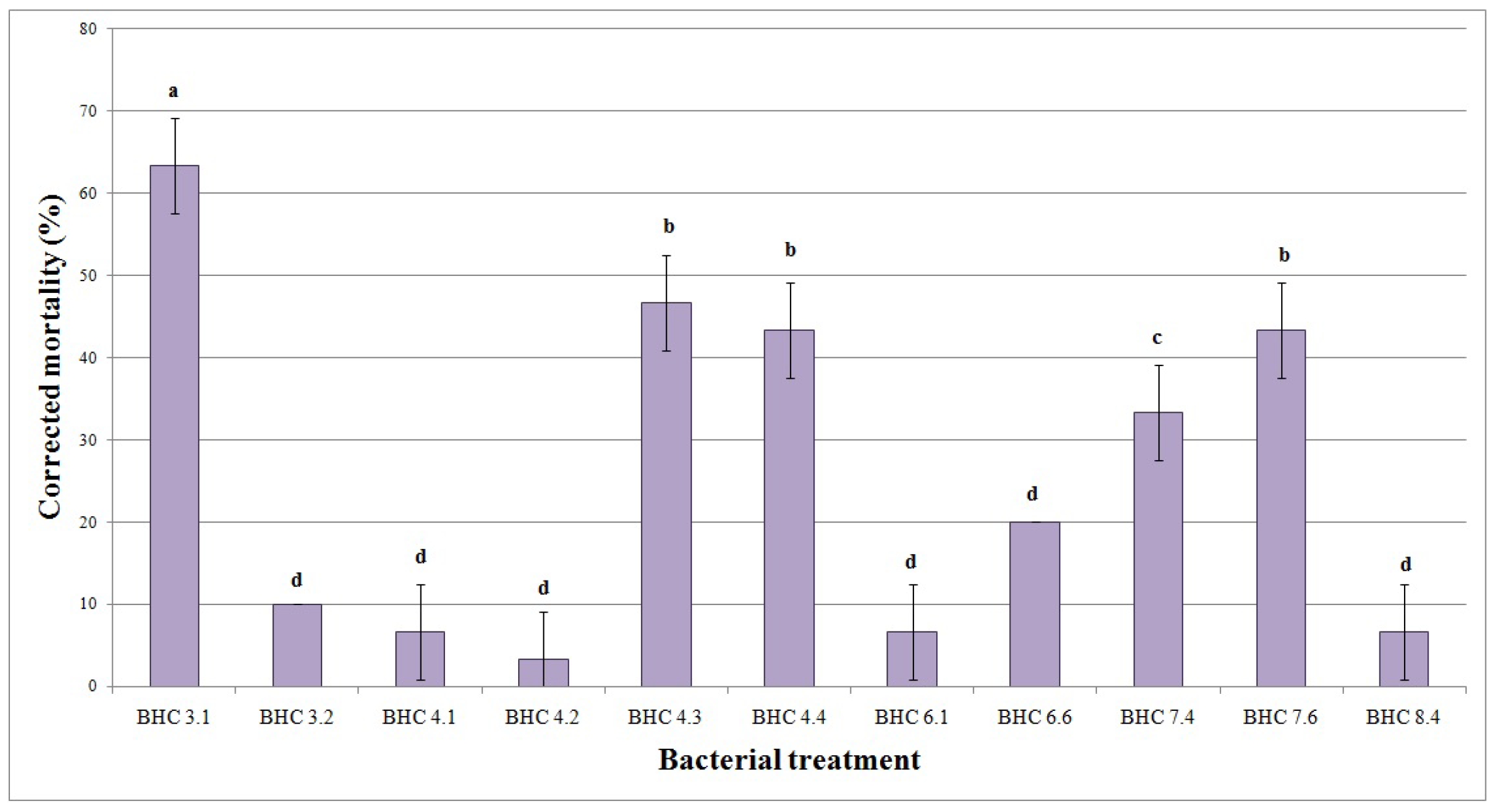

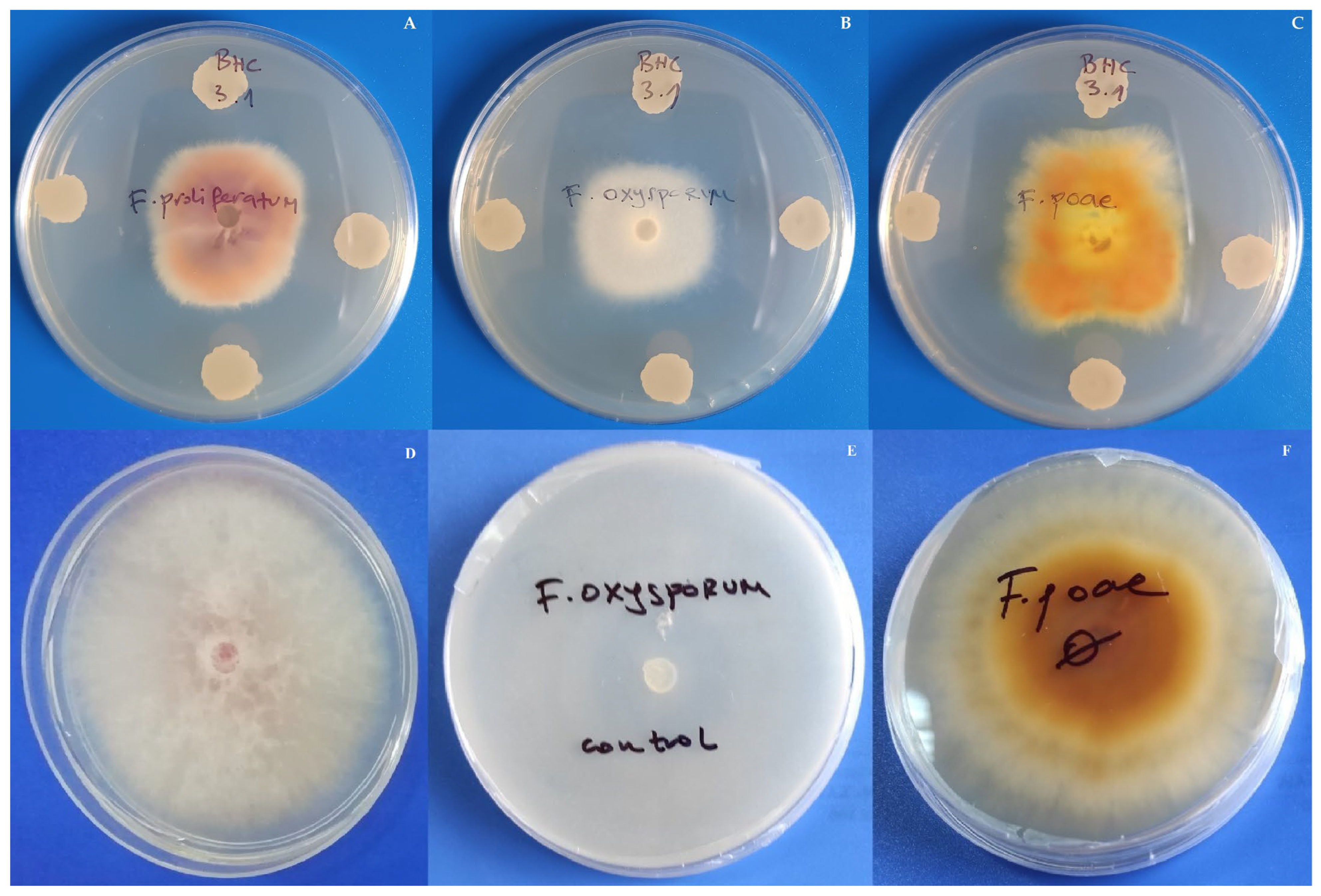

3.1. Plant Growth Promoting and Biocontrol Potential of Bacterial Isolates

3.2. Molecular Identification of Bacterial Isolates

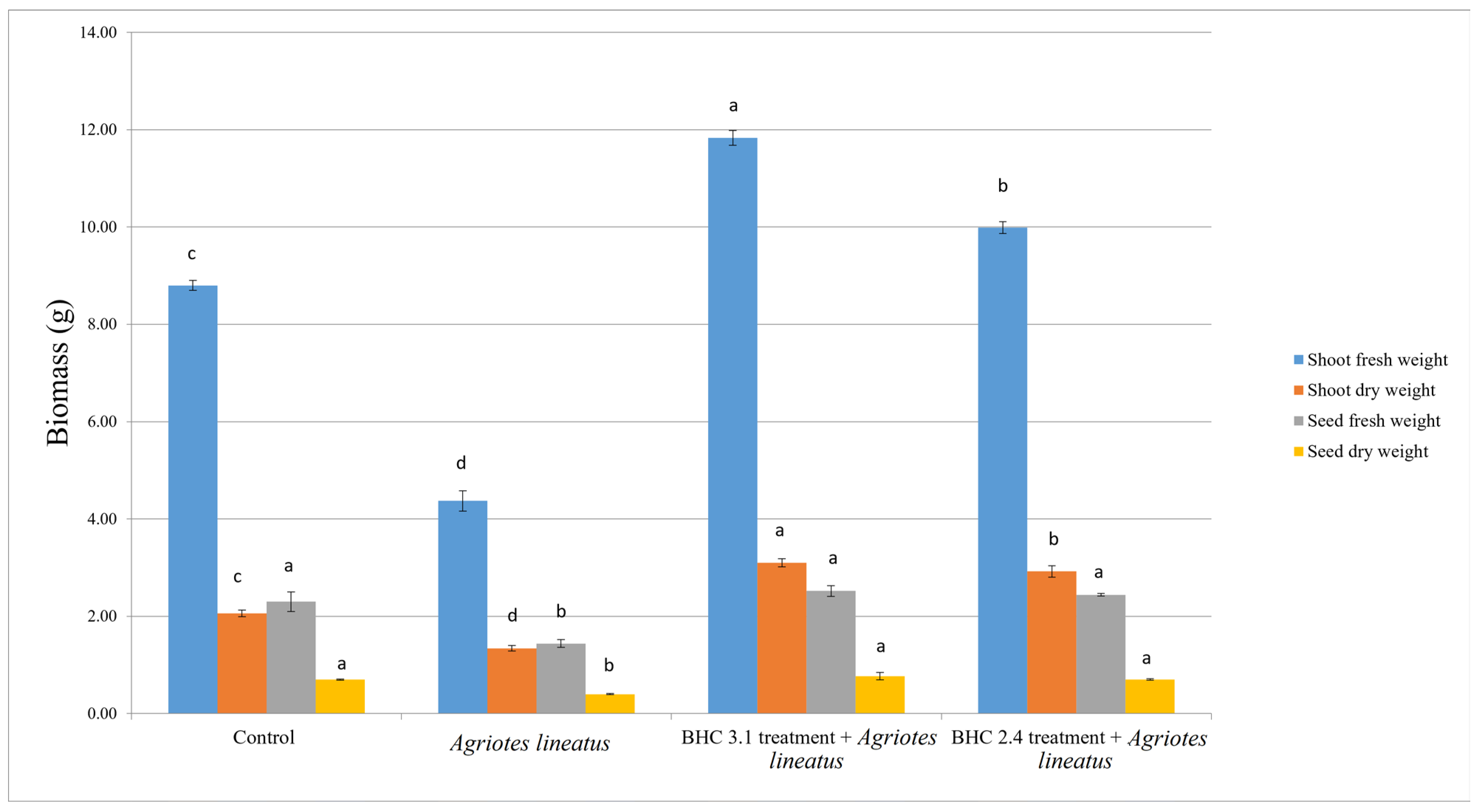

3.3. Impact of Bacillus Inoculation on Oat Plants Infested by Agriotes lineatus

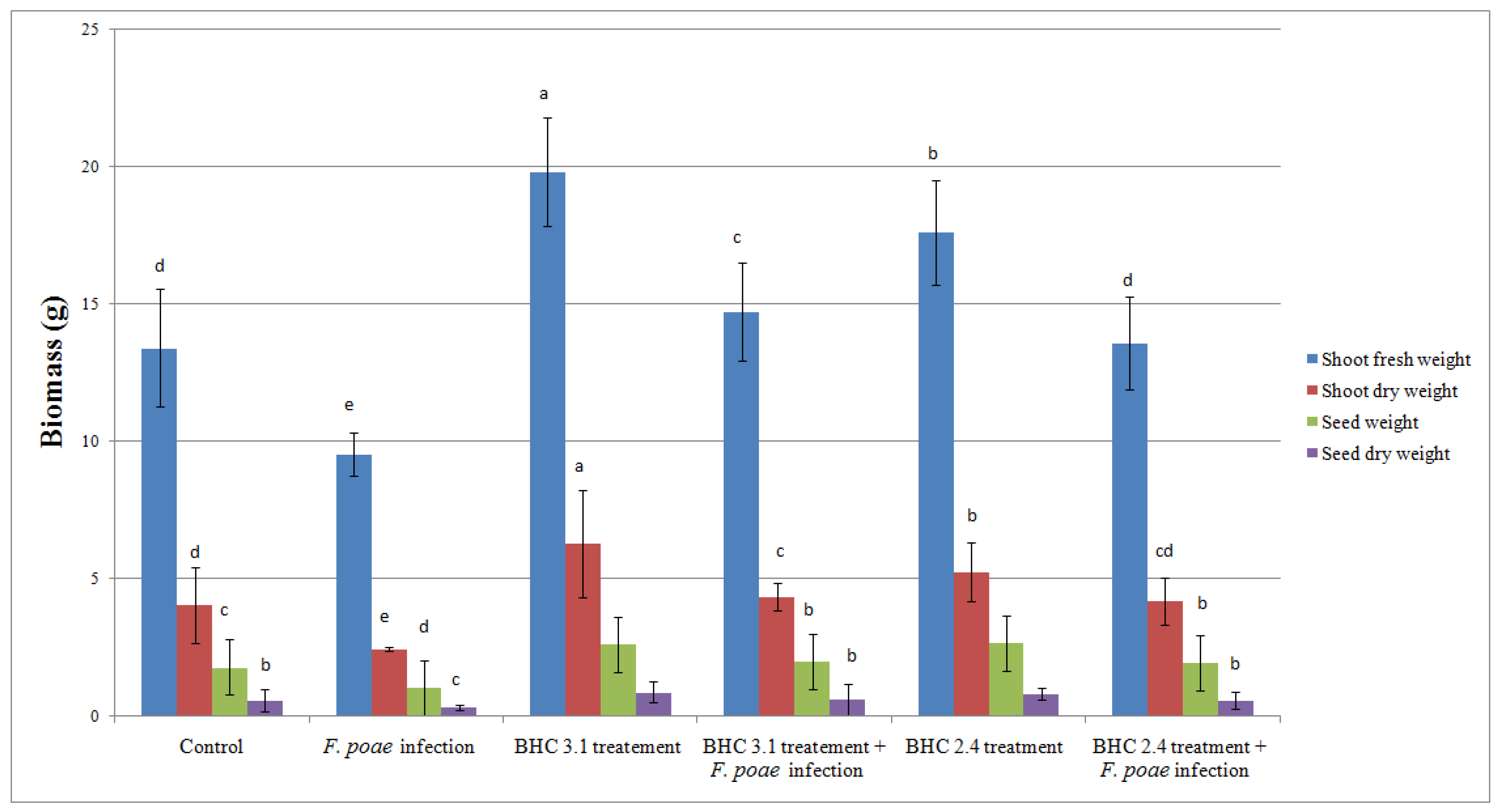

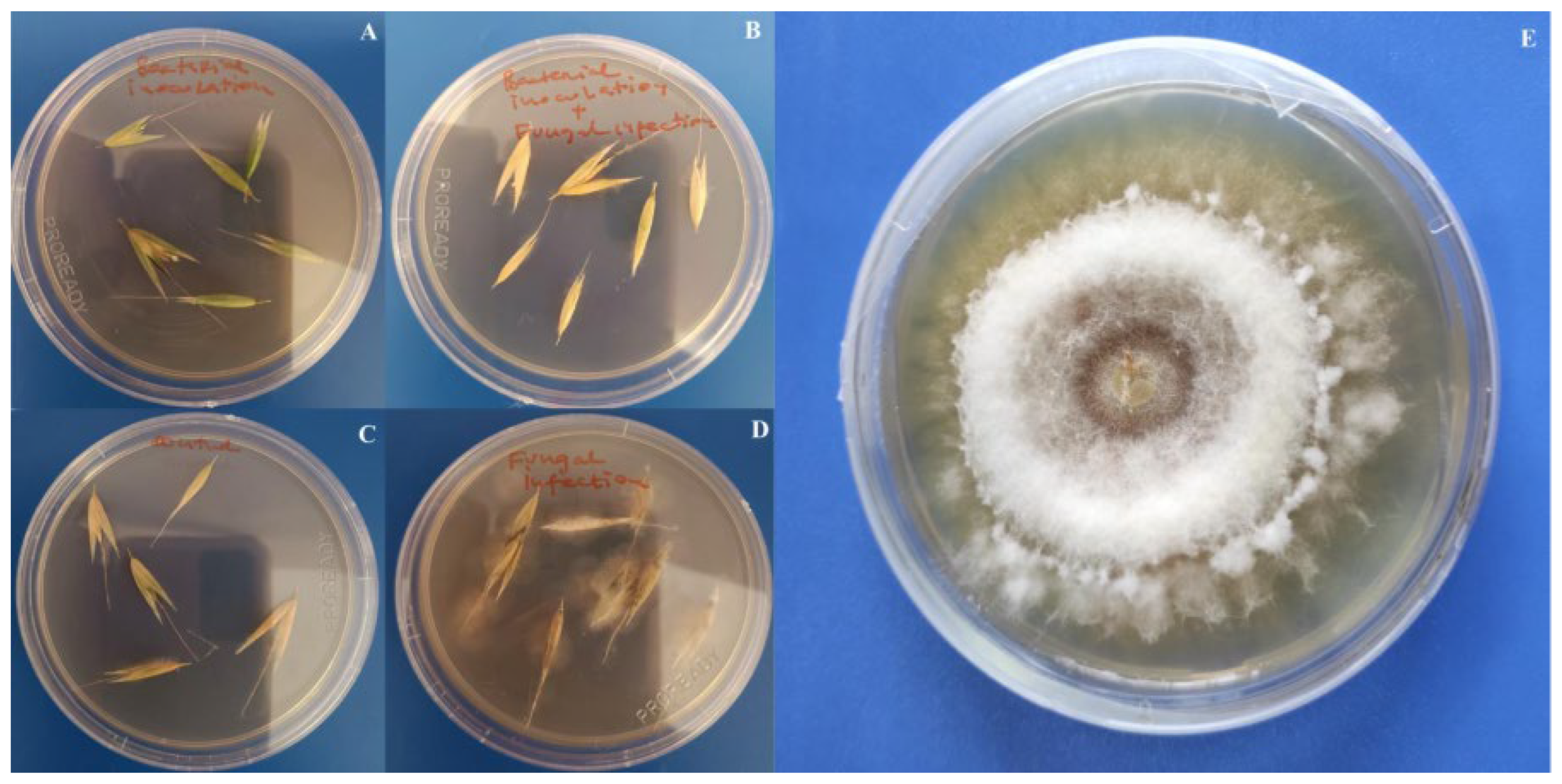

3.4. Impact of Bacillus Inoculation on Oat Plants Infected by Fusarium poae

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGP | plant growth-promoting |

| PGPR | plant growth-promoting Rhizobacteria |

| NA | nutrient agar |

| EPS | exopolysaccharides |

| SID | siderophores |

| IAA | indole-3-acetic acid |

| CAS | Chrome Azurol agar |

| Flav | arbitrary units, indicating relative accumulation of flavonoid compounds |

| Anth | arbitrary units, indicating relative accumulation of anthocyanin pigments |

References

- POWO. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Joyce, S.A.; Kamil, A.; Fleige, L.; Gahan, C.G.M. The Cholesterol-Lowering Effect of Oats and Oat Beta Glucan: Modes of Action and Potential Role of Bile Acids and the Microbiome. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D.; Dhungana, B.; Caffe, M.; Krishnan, P. A review of health-beneficial properties of oats. Foods 2021, 10, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakić, R.; Ikanović, J.; Popović, V.; Rakić, S.; Janković, S.; Ristić, V.; Petković, Z. Environment and digestate affect on the oats quality and yield parametars. Agric. For. 2023, 69, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Ahad, I.; Dorjey, S.; Arifie, U.; Aafreen Rehman, S. A review on insect pest comlex of oat (Avena sativa L.). Int. J. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2017, 6, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcia, C.; Terzi, V.; Ghizzoni, R.; Carrara, I.; Gazzetti, K. Looking for Fusarium resistance in Oat: An update. Agronomy 2024, 14, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottalico, A.; Perrone, G. Toxigenic Fusarium species and mycotoxins associated with head blight in small-grain cereals in Europe. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2002, 108, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, M.; Benefer, C.M.; Blackshaw, R.P.; van Herk, W.G.; Vernon, R.S. Biology, ecology, and control of elaterid beetles in agricultural land. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015, 60, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Rodriguez, A.; O’Neill, R.P.; Wanner, K.W. A survey of wireworm (Coleoptera: Elateridae) species infesting cereal crops in Montana. Pan-Pac. Entomol. 2014, 90, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knodel, J.J.; Shrestha, G. Pulse crops: Pest management of wireworms and cutworms in the Northern Great Plains of United States and Canada. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2018, 111, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, S.; Le Cointe, R.; Lehmhus, J.; Plantegenest, M.; Furlan, L. Alternative Strategies for Controlling Wireworms in Field Crops: A Review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, R.S.; van Herk, W.G. Wireworms as Pests of Potato. In Insect Pests of Potato, 2nd ed.; Alyokhin, A., Rondon, S.I., Gao, Y., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2013; Chapter 7; pp. 103–164. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, L. IPM thresholds for Agriotes wireworm species in maize in Southern Europe. J. Pest. Sci. 2014, 87, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Reddy, G.V. Evaluation of trap crops for the management of wireworms in spring wheat in Montana. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2017, 11, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunke, A.; O’keefe, L.; Bahlai, C.; Sears, M.; Hallett, R. Guilty by association: An evaluation of millipedes as pests of carrot and sweet potato. J. Appl. Entomol. 2012, 136, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, A.; Häberli, M.; Stamp, P. Quality deficiencies on potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers caused by Rhizoctonia solani, wireworms (Agriotes ssp.) and slugs (Deroceras reticulatum, Arion hortensis) in different farming systems. Field Crops Res. 2012, 128, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, J.; Soares Chaves, M.; Sganzerla Graichen, F.A.; Federizzi, L.C.; Dresch, L.F. Impact of Fusarium Head Blight in Reducing the Weight of Oat Grains. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 6, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikka, H.; Manninen, O.; Hautsalo, J.; Pietilä, L.; Jalli, M.; Veteläinen, M. Genome-wide Association Study and Genomic Prediction for Fusarium graminearum Resistance Traits in Nordic Oat (Avena sativa L.). Agronomy 2020, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, T.E.; Hicks, C.; Hermans, A.; Shields, S.; Overy, D.P. Debunking the myth of Fusarium poae T-2/HT-2 toxin production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 3949–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöneberg, T.; Jenny, E.; Wettstein, F.E.; Bucheli, T.D.; Mascher, F.; Bertossaa, M.; Musa, T.; Seifert, K.; Gräfenhan, T.; Keller, B.; et al. Occurrence of Fusarium species and mycotoxins in Swiss oats—Impact of cropping factors. Eur. J. Agron. 2018, 92, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielewicz, J.; Jajor, E.; Horoszkiewicz, J.; Korbas, M.; Blecharczyk, A.; Idziak, R.; Sobiech, Ł.; Grzanka, M.; Szymański, T. Protection of oats against Puccinia and Drechslera fungi in various meteorological conditions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsiuk, N.; Bakalova, A.; Ribitska, G.; Denysiuk, Y.; Liubakivskyi, O. The efficiency of seed treatment in oats cultivation in conditions of the Ukrainian forest-steppe. Sci. Horizo. 2020, 8, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.J.; Hawkins, J.N.; Fraaije, A.B. The evolution of fungicide resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 90, 29–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes de Chaves, M.; Reginatto, P.; Souza da Costa, B.; Itiki de Paschoal, R.; Lettieri Teixeira, M.; Meneghello Fuentefria, A. Fungicide Resistance in Fusarium graminearum Species Complex. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Mosqueda, M.D.C.; Flores, A.; Rojas-Sánchez, B.; Urtis-Flores, C.A.; Morales-Cedeño, L.R.; Valencia-Marin, M.F.; Chávez-Avila, S.; Rojas-Solis, D.; Santoyo, G. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria as Bioinoculants: Attributes and Challenges for Sustainable Crop Improvement. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfte, H.; Whiteley, H.R. Insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol. Rev. 1989, 53, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaisse, H.; Lereclus, D. How does Bacillus thuringiensis produce so much insecticidal crystal protein? J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 6027–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lereclus, D.; Agaisse, H.; Grandvalet, C.; Salamitou, S.; Gominet, M. Regulation of Bacillus thuringiensis virulence gene expression. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2000, 290, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Peng, Q.; Song, F.; Lereclus, D. Regulation of cry Gene Expression in Bacillus thuringiensis. Toxins 2014, 6, 2194–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Vazquez, M.C.; Vela-Sanchez, R.A.; Rojas-Ruiz, N.E.; Carabarin-Lima, A. Importance of Cry Proteins in Biotechnology: Initially a Bioinsecticide, Now a Vaccine Adjuvant. Life 2021, 11, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, M.F.; Bellier, A.; Balasubramani, V.; Hu, Y.; Hsu, W.; Nielsen-LeRoux, C.; McGillivray, S.M.; Nizet, V.; Aroian, R.V. The pore-forming protein Cry5B elicits the pathogenicity of Bacillus sp. against Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e29122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnepf, E.; Crickmore, N.; Van Rie, J. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 775–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, A.; Gill, S.S.; Soberón, M. Mode of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry and Cyt toxins and their potential for insect control. Toxicon 2007, 49, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhang, X.; Chou, S.H.; Wang, J.; He, J. Which Is Stronger? A Continuing Battle Between Cry Toxins and Insects. Fron. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 665101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dervišević Milenković, M.; Knežević, M.; Jovković, M.; Maksimović, J.; Buzurović, U.; Pavlović, J.; Buntić, A. Sustainable Wireworm Control in Wheat via Selected Bacillus thuringiensis Strains: A Biocontrol Perspective. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knežević, M.; Dervišević, M.; Jovković, M.; Jevđenović, G.; Maksimović, J.; Buntić, A. Versatile role of Bacillus velezensis: Biocontrol of Fusarium poae and wireworms and barley plant growth promotion. Biol. Control 2025, 206, 105789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.A.; Weber, R.P. Colorimetric estimation of indoleacetic acid. Plant Physiol. 1951, 26, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milagres, A.M.F.; Machuca, A.; Napoleão, D. Detection of siderophore production from several fungi and bacteria by a modification of chrome azurol S (CAS) agar plate assay. J. Microbiol. Methods 1999, 37, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhbakhsh-Zamin, F.; Sachdev, D.; Kazemi-Pour, N.; Engineer, A.; Pardesi, K.R.; Zinjarde, S.; Dhakephalkar, P.K.; Chopade, B.A. Characterization of plant-growth-promoting traits of Acinetobacter species isolated from rhizosphere of Pennisetum glaucum. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 21, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkić, I.; Živković, S.; Berić, T.; Ivanović, Ž.; Gavrilović, V.; Stanković, S.; Fira, D. Characterization and evaluation of two Bacillus strains, SS-12.6 and SS-13.1, as potential agents for the control of phytopathogenic bacteria and fungi. Biol. Control 2013, 65, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, I.M.R.; Cabrefiga, J.; Montesinos, E. Antimicrobial peptide genes in Bacillus strains from plant environments. Int. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Yan, G.; Huang, S.; Geng, Y.; Soberón, M.; Bravo, A.; Geng, L.; Zhang, J. Characterization of Two Novel Bacillus thuringiensis Cry8 Toxins Reveal Differential Specificity of Protoxins or Activated Toxins against Chrysomeloidea Coleopteran Superfamily. Toxins 2020, 12, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, D.; Bel, Y.; Menezes de Moura, S.; Jurat-Fuentes, J.L.; Grossi de Sa, M.F.; Robles-Fort, A.; Escriche, B. Distinct Impact of Processing on Cross-Order Cry1I Insecticidal Activity. Toxins 2025, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Sunda, S.D.; Sanadhya, S.; Nath, D.J.; Khandelwal, S.K. Molecular characterization and PCR-based screening of cry genes from Bacillus thuringiensis strains. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammasittirong, A.; Attathom, T. PCR-based method for the detection of cry genes in local isolates of Bacillus thuringiensis from Thailand. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2008, 98, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, M.; Amaresan, N.; Sankaranarayanan, A. Plant-microbe interactions. In Springer Protocols Handbooks; Senthilkumar, M., Amaresan, N., Sankaranarayanan, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, J.E.; Rincon, M.C.; Orduz, S. Diversity of Bacillus thuringiensis strains from Latin America. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5269–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danismazoglu, M.; Demir, İ.; Sevim, A.; Demirbag, Z.; Nalcacioglu, R. An investigation on the bacterial flora of Agriotes lineatus (Coleoptera: Elateridae) and pathogenicity of the Flora members. Crop Protect. 2012, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbebor, N.; Adekunle, A.T. Inhibition of conidial germination and mycelial growth of Corynespora cassiicola (Berk and Curt) of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis muell. Arg.) using extracts of some plants. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 4, 996–1000. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajb/article/view/71145/0 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Buntić, A.; Jelušić, A.; Milić, M.; Dimitrijević, S.; Buzurović, U.; Milinković, M.; Knežević, M. Antimicrobial peptides (AMP)-producing Bacillus spp. for the management of Fusarium infection and alfalfa growth promotion. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 8283–8293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draganić, V.; Lozo, J.; Biočanin, M.; Dimkić, I.; Garalejić, E.; Fira, Đ.; Stanković, S.; Berić, T. Genotyping of Bacillus spp. isolate collection from natural samples. Genetika 2017, 49, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horneck, D.A.; Miller, R.O. Determination of Total Nitrogen in Plant Tissue. In Handbook of Reference Methods for Plant Analysised; Kalra, Y.P., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 1998; Chapter 9; pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- DomínguezArrizabalaga, M.; Villanueva, M.; Escriche, B.; AncínAzpilicueta, C.; Caballero, P. Insecticidal Activity of Bacillus thuringiensis Proteins against Coleopteran Pests. Toxins 2020, 12, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumyantsev, S.D.; Alekseev, V.Y.; Sorokan, A.V.; Burkhanova, G.F.; Cherepanova, E.A.; Garafutdinov, R.R.; Maksimov, I.G.; Veselova, S.T. Additive effect of the composition of Endophytic Bacteria Bacillus subtilis on systemic resistance of wheat against Greenbug Aphid Schizaphis graminum due to Lipopeptides. Life 2023, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L. Lipopeptides from Bacillus velezensis ZLP-101 and their mode of action against bean aphids Acyrthosiphon pisum Harris. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhuang, W.; Zeng, Z. Bacillus velezensis BV01 Has Broad-Spectrum Biocontrol Potential and the Ability to Promote Plant Growth. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lv, W.; Zhang, S.; Du, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; et al. Bacillus velezensis SS-20 as a potential and efficient multifunctional agent in biocontrol, saline-alkaline tolerance, and plant-growth promotion. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2025, 205, 105772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Su, S.; Bo, S.; Zheng, B.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Xu, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, P.; Fan, K.; et al. A Bacillus velezensis strain isolated from oats with disease-preventing and growth-promoting properties. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Dai, J.; Xu, Z.; Diao, Y.; Yang, N.; Fan, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Gao, S.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation and mechanisms of Bacillus velezensis ax22 against Rice bacterial blight. Biol. Control 2025, 207, 105820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspareto, R.N.; Jalal, A.; Ito, W.C.N.; Oliveira, C.E.D.S.; Garcia, C.M.D.P.; Boleta, E.H.M.; Rosa, P.A.L.; Galindo, F.S.; Buzetti, S.; Ghaley, B.B.; et al. Inoculation with Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria and Nitrogen Doses Improves Wheat Productivity and Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gao, D.; Zhang, L.; Guo, L.; Ge, J.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Z. Study on Optimal Nitrogen Application for Different Oat Varieties in Dryland Regions of the Loess Plateau. Plants 2024, 13, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacterial Isolate | Identity 16S rRNA | Identity tuf | NCBI Accession Number | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHC 3.1 | 99.89% | 99.83% | PX482504 | B. velezensis |

| BHC 3.2 | 99.53% | 99.82% | PX482503 | B. mycoides |

| BHC 4.1 | 100% | 100% | PX482507 | B. pumilus |

| BHC 4.2 | 100% | 99.56% | PX482521 | B. pseudomycoides |

| BHC 4.3 | 100% | 100% | PX482522 | B. safensis |

| BHC 4.4 | 100% | 99.78% | PX482523 | Peribacillus frigotolerans |

| BHC 6.1 | 100% | 99.60% | PX482525 | B. pseudomycoides |

| BHC 6.6 | 99.83% | 100% | PX482528 | B. toyonensis |

| BHC 7.4 | 99.60% | 100% | PX482529 | B. toyonensis/B. thuringiensis |

| BHC 7.6 | 100% | 100% | PX482535 | B. mycoides |

| BHC 8.4 | 99.88% | 100% | PX482537 | B. pseudomycoides |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Buntić, A.; Dervišević Milenković, M.; Pavlović, J.; Buzurović, U.; Maksimović, J.; Jovković, M.; Knežević, M. Unlocking the Potential of Bacillus Strains for a Two-Front Attack on Wireworms and Fungal Pathogens in Oat. Insects 2026, 17, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010028

Buntić A, Dervišević Milenković M, Pavlović J, Buzurović U, Maksimović J, Jovković M, Knežević M. Unlocking the Potential of Bacillus Strains for a Two-Front Attack on Wireworms and Fungal Pathogens in Oat. Insects. 2026; 17(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuntić, Aneta, Marina Dervišević Milenković, Jelena Pavlović, Uroš Buzurović, Jelena Maksimović, Marina Jovković, and Magdalena Knežević. 2026. "Unlocking the Potential of Bacillus Strains for a Two-Front Attack on Wireworms and Fungal Pathogens in Oat" Insects 17, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010028

APA StyleBuntić, A., Dervišević Milenković, M., Pavlović, J., Buzurović, U., Maksimović, J., Jovković, M., & Knežević, M. (2026). Unlocking the Potential of Bacillus Strains for a Two-Front Attack on Wireworms and Fungal Pathogens in Oat. Insects, 17(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010028