Effectiveness of Repellent Plants for Controlling Potato Tuber Moth (Symmetrischema tangolias) in the Andean Highlands

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Climate Data

2.3. Plant Material

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Experimental Management

2.6. Storage Variables Evaluated

2.6.1. Incidence of Moth Attack (%)

2.6.2. Moth Damage Severity (%)

2.6.3. Live Larvae Count

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Incidence of Moth Attack (%) in Huaytorco and Samaday

3.2. Moth Damage Severity (%) in Huaytorco and Samaday

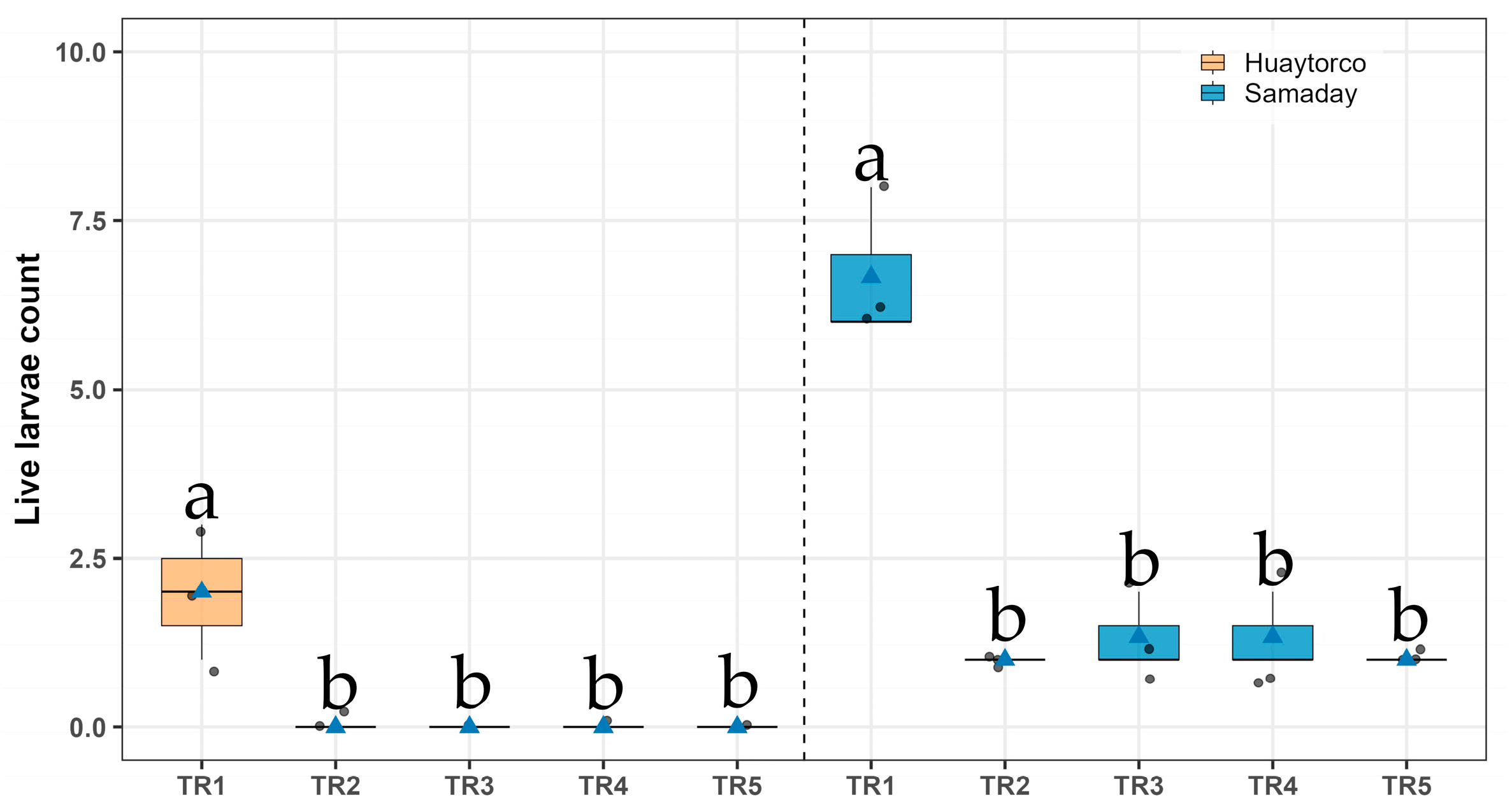

3.3. Live Larvae Count in Huaytorco and Samaday

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beumer, K.; Stemerding, D. A Breeding Consortium to Realize the Potential of Hybrid Diploid Potato for Food Security. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 1530–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jian, Y.; Dong, D.; Huang, S.; et al. The Gap-Free Potato Genome Assembly Reveals Large Tandem Gene Clusters of Agronomical Importance in Highly Repeated Genomic Regions. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.K.; Sharma, S.; Shah, M.A. Sustainable Management of Potato Pests and Diseases; Swarup, K., Sanjeev, S., Mohd Abas, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; ISBN 9789811676956. [Google Scholar]

- Triveño, G. Estudio de Potencial Demanda de Variedades de Papa Biofortificadas y Variedades Para Procesamiento; International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Riego. Perfil Productivo y Competitivo de los Principales Cultivos del Sector. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYjYwYTk5MDgtM2M0MS00NDMyLTgzNDEtMjNhNjEzYWQyOTNlIiwidCI6IjdmMDg0NjI3LTdmNDAtNDg3OS04OTE3LTk0Yjg2ZmQzNWYzZiJ9 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego. Indicadores Productivos y Económicos del Cultivo de la Papa; Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego: Lima, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cayetano, P.; Peña, K.; Olivarez, E.; Vargas, S. Estudio de Vigilancia Tecnológica en el Cultivo de Papa; Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria: Lima, Peru, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, L.; Suárez, V.; Thiele, G. Estudio de la Adopción de Variedades de Papa en Zonas Pobres del Perú; International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thiele, G.; Hareau, G.; Suárez, V.; Chujoy, E.; Bonierbale, M.; Maldonado, L. Varietal Change in Potatoes in Developing Countries and the Contribution of the International Potato Center: 1972–2007; International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, M.; Ali, A.; Du, X.; Mei, X.; Gao, Y. Optimization and Field Evaluation of Sex-Pheromone of Potato Tuber Moth, Phthorimaea Operculella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 3903–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Rondon, S.I.; Gao, Y. Synthesis and Bioactivity Studies of the Potato Tuber Moth, Phthorimaea Operculella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) Sex Pheromone Analogs. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 81, 7381–7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.D.; Wu, S.Y.; Yan, J.J.; Reitz, S.; Gao, Y.L. Establishment of Beauveria Bassiana as a Fungal Endophyte in Potato Plants and Its Virulence against Potato Tuber Moth, Phthorimaea Operculella (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Insect Sci. 2023, 30, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañedo, V.; Dávila, W.; Carhuapoma, P.; Kroschel, J.; Kreuze, J. A Temperature-Dependent Phenology Model for Apanteles Subandinus Blanchard, Parasitoid of Phthorimaea Operculella Zeller and Symmetrischema Tangolias (Gyen). J. Appl. Entomol. 2022, 146, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroschel, J.; Cañedo, V.; Alcázar, J.; Miethbauer, T. Manejo de Plagas de la Papa en la Región Andina del Perú: Guía de Capacitación; International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón, R. Desarrollo de Componentes del Manejo Integrado de las Polillas de la Papa (Phthorimaea Operculella y Symme-Trischema Tangolias) en Bolivia y el Bioinsecticida Baculovirus (Matapol); Fundacion Proinpa: Cochabamba, Bolivia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moawad, S.S.; Ebadah, I.M.A. Impact of Some Natural Plant Oils on Some Biological Aspects Of the Potato Tuber Moth, Phthorimaea Opercullela, (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2007, 3, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. Biopesticides: A Need for Food and Environmental Safety. J. Biofertil. Biopestic. 2012, 3, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divekar, P. Botanical Pesticides: An Eco-Friendly Approach for Management of Insect Pests. Acta Sci. Agric. 2023, 7, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christaki, E.; Bonos, E.; Giannenas, I.; Florou-Paneri, P. Aromatic Plants as a Source of Bioactive Compounds. Agriculture 2012, 2, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greff, B.; Sáhó, A.; Lakatos, E.; Varga, L. Biocontrol Activity of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants and Their Bioactive Components against Soil-Borne Pathogens. Plants 2023, 12, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysargyris, A.; Skaltsa, H.; Konstantopoulou, M. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs): The Connection between Cultivation Practices and Biological Properties. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, T.; Sivakumar, D.T. A Systematic Review on Traditional Medicinal Plants Used for Traditional Control of Insects. Int. J. Bot. Stud. 2022, 7, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Henagamage, A.P.; Ranaweera, M.N.; Peries, C.M.; Premetilake, M.M.S.N. Repellent, Antifeedant and Toxic Effects of Plants-Extracts against Spodoptera Frugiperda Larvae (Fall Armyworm). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 48, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradel, W.; Hareau, G.; Quintanilla, L.; Suárez, V. Adopcion e Impacto de Variedades Mejoradas de Papa en el Peru: Resultados de Una Encuesta a Nivel Nacional (2013); International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baca, P.; Ríos, F. Niveles y Umbrales de Daños Económicos de las Plagas; Zamorano-Escuela Agrícola Panamericana: Tegucigalpa, Honduras, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz, R.; Ramírez, D.A.; Kroschel, J.; Andrade-Piedra, J.; Barreda, C.; Condori, B.; Mares, V.; Monneveux, P.; Perez, W. Impact of Climate Change on the Potato Crop and Biodiversity in Its Center of Origin. Open Agric. 2018, 3, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.M.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, K.H.; Jeon, S.W.; Jung, S.; Lee, W.H. The Potential Distribution of the Potato Tuber Moth (Phthorimaea Operculella) Based on Climate and Host Availability of Potato. Agronomy 2019, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, B.; Poudel, A.; Aryal, S. The Impact of Climate Change on Insect Pest Biology and Ecology: Implications for Pest Management Strategies, Crop Production, and Food Security. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Benítez, N.; Torralbo-Cabrera, Y.P.; Stashenko, E.E. Actividad Repelente e Insecticida de Cuatro Aceites Esenciales de Plantas Recolectadas En Chocó-Colombia Contra Tribolium Castaneum. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromat. 2024, 23, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves, E.; Fernández Méndez, J.; Lias, J.; Rondón, M.; Briceño, B. Actividad Repelente de Aceites Esenciales Contra Las Picaduras de Lutzomyia Migonei (Diptera: Psychodidae). Rev. Biol. Trop. 2010, 58, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, P.C.; Molina, I.Y.; Yábar, E.; Gianoli, E. Oviposition Deterrence of Shoots and Essential Oils of Minthostachys spp. (Lamiaceae) against the Potato Tuber Moth. J. Appl. Entomol. 2007, 131, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Quispe, L.; Pino, J.A.; Tomaylla-Cruz, C.; Aragón-Alencastre, L.J.; Solís-Quispe, A.; Solís-Quispe, J.A. Chemical Composition and Larvicidal Activity of the Essential Oils from Minthostachys Spicata (Benth) Epling and Clinopodium Bolivianum (Benth) Kuntze against Premnotrypes Latithorax Pierce. Am. J. Essent. Oils Nat. Prod. 2018, 6, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sofi, M.A.; Nanda, A.; Sofi, M.A.; Maduraiveeran, R.; Nazir, S.; Siddiqui, N.; Nadeem, A.; Shah, Z.A.; Rehman, M.U. Larvicidal Activity of Artemisia Absinthium Extracts with Special Reference to Inhibition of Detoxifying Enzymes in Larvae of Aedes aegypti L. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajilov-Krstev, T.; Jovanović, B.; Jović, J.; Ilić, B.; Miladinović, D.; Matejić, J.; Rajković, J.; Äorević, L.; Cvetković, V.; Zlatković, B. Antimicrobial, Antioxidative, and Insect Repellent Effects of Artemisia Absinthium Essential Oil. Planta Medica 2014, 80, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Guleria, N.; Deeksha, M.G.; Kumari, N.; Kumar, R.; Jha, A.K.; Parmar, N.; Ganguly, P.; de Aguiar Andrade, E.H.; Ferreira, O.O.; et al. From an Invasive Weed to an Insecticidal Agent: Exploring the Potential of Lantana Camara in Insect Management Strategies—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalvenzi, L.; Durofil, A.; Cáceres Claros, C.; Pérez Martínez, A.; Guardado Yordi, E.; Manfredini, S.; Baldini, E.; Vertuani, S.; Radice, M. Unleashing Nature’s Pesticide: A Systematic Review of Schinus Molle Essential Oil’s Biopesticidal Potential. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, N.C.; Retamozo, R.C. Potato Moth Control with Local Plants in the Storage of Potato. In Natural Crop Protection in the Tropic; Stoll, G., Ed.; Margraf Verlag: Weikersheim, Germany, 2000; pp. 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, A.; Sisay, A. Evaluation of Some Botanicals to Control Potato Tuber Moth Phothoromaea Operculella (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) at Bako, West Shoa, Ethiopia. E. Afr. J. Sci. 2011, 5, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaby, A.; Abdel-Rhman, H.; Abdel-Aziz, S.; Moawad, S.S. Susceptibility of Different Potato Varieties to Infestation by Potato Tuber Moth and Role of the Plant Powders on Their Protection. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2014, 7, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza Choqque, L.M. Especies de la Polilla de Papa y Efecto Repelencia de Plantas Aromáticas en Papa Nativa Wankucho (s. Tuberosum Ssp. Andigena) en Almacenes de Santo Tomas-Chumbivilcas 2014; Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco: Cusco, Peru, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Giri, Y.P.; Thapa, R.B.; Dangi, N.; Aryal, S.; Shrestha, S.M.; Pradhan, S.B.; Sporleder, M. Distribution and Seasonal Abundance of Potato Tuber Moth: Phthorimaea Operculella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Nepal. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 2, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, L. Studies on Natural Repellents against Potato Tuber Moth (Phthorimaea Operculella Zeller) in Country Stores. Potato Res. 1987, 30, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, R.S.; Kumar, R.; Kashyap, N.P. Bioecology of Potato Tuber Moth, Phthorimaea Operculella Zeller in Mid Hills of Himachal Pradesh. J. Entomol. Res. 2001, 25, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Mazrou, K.; Labdelli, F.; Bousmaha, F.; Chelef, M.; Adamou-Djerbaoui, M. The Efficacy of Three Different Plant Extracts on Some Biological Features of the Potato Tuber Moth, Phthorimaea Operculella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) by Different Application Methods. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 78, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hamed, N.A.; Shaalan, H.S.; Fargalla, F.H.H. Effectiveness of Some Plant Powders and Bioinsecticides against Phthorimaea Operculella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) on Some Potato Cultivars. J. Plant Prot. Pathol. 2011, 2, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.K.; Chahil, G.; Goyal, G.; Gill, A.; Gillett-Kaufman, J.L. Potato Tuberworm Phthorimaea Operculella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Available online: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1031 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Koller, J.; Gonthier, J.; Norgrove, L.; Arnó, J.; Sutter, L.; Collatz, J. A Parasitoid Wasp Allied with an Entomopathogenic Virus to Control Tuta Absoluta. Crop Prot. 2024, 179, 106617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, B.; Prasad Mainali, R.; Aryal, S. Biopesticides as a Promising Alternative to Control Potato Tubermoth, Phthorimaea Operculella (Zeller 1873), in Potatoes Underfarmer Storage Conditions. In Proceedings of the 15th National Outreach Research Workshop, Kaski, Nepal, 15–16 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beniaich, G.; Mabchour, I.; Mssillou, I.; Lfitat, A.; El Kamari, F.; Allali, A.; Hosen, M.E.; Supti, S.J.; Bin Jardan, Y.A.; Shazly, G.A.; et al. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Insecticidal Properties of Chemically Characterized Essential Oils Isolated from Artemisia Herba-Alba: In Vivo, in Vitro, and in Silico Approaches. Plant Biosyst.—Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2025, 159, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadoglidou, K.I.; Chatzopoulou, P. Approaches and Applications of Mentha Species in Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Description | Dose (g/15 kg) |

|---|---|---|

| TR-1 | Control | --- |

| TR-2 | Dried leaves of Marco (Ambrosia peruviana) | 200 g/15 kg of seed potato |

| TR-3 | Dried leaves of Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) | 200 g/15 kg of seed potato |

| TR-4 | Dried leaves of Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) | 200 g/15 kg of seed potato |

| TR-5 | Dried leaves of Muña (Minthostachys mollis) | 200 g/15 kg of seed potato |

| Treatments | Location | Incidence (%) | Severity (%) | Live Larvae Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR1 | Huaytorco | 3.11 a ± 1.11 | 30.0 a ± 2.89 | 2.0 a ± 0.58 |

| TR2 | Huaytorco | 1.99 ab ± 0.67 | 11.67 b ± 1.67 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 |

| TR3 | Huaytorco | 2.00 ab ± 0.77 | 10.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 |

| TR4 | Huaytorco | 0.00 b ± 0.0 | 0.00 c ± 0.00 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 |

| TR5 | Huaytorco | 1.33 ab ± 0.00 | 15.00 b ± 2.89 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 |

| TR1 | Samaday | 95.55 a ± 1.35 | 80.0 a ± 5.00 | 6.67 a ± 0.67 |

| TR2 | Samaday | 12.00 b ± 3.06 | 20.00 b ± 2.89 | 1.00 b ± 0.00 |

| TR3 | Samaday | 9.56 b ± 4.06 | 11.67 b ± 1.67 | 1.33 b ± 0.33 |

| TR4 | Samaday | 3.33 b ± 0.77 | 9.00 b ± 3.78 | 1.33 b ± 0.33 |

| TR5 | Samaday | 3.55 b ± 1.89 | 6.67 b ± 1.67 | 1.00 b ± 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Villanueva, A.; Escobal, F.; Cabrera, H.; Cántaro-Segura, H.; Diaz-Morales, L.; Matsusaka, D. Effectiveness of Repellent Plants for Controlling Potato Tuber Moth (Symmetrischema tangolias) in the Andean Highlands. Insects 2026, 17, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010024

Villanueva A, Escobal F, Cabrera H, Cántaro-Segura H, Diaz-Morales L, Matsusaka D. Effectiveness of Repellent Plants for Controlling Potato Tuber Moth (Symmetrischema tangolias) in the Andean Highlands. Insects. 2026; 17(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillanueva, Alex, Fernando Escobal, Héctor Cabrera, Héctor Cántaro-Segura, Luis Diaz-Morales, and Daniel Matsusaka. 2026. "Effectiveness of Repellent Plants for Controlling Potato Tuber Moth (Symmetrischema tangolias) in the Andean Highlands" Insects 17, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010024

APA StyleVillanueva, A., Escobal, F., Cabrera, H., Cántaro-Segura, H., Diaz-Morales, L., & Matsusaka, D. (2026). Effectiveness of Repellent Plants for Controlling Potato Tuber Moth (Symmetrischema tangolias) in the Andean Highlands. Insects, 17(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects17010024