Unraveling the Impacts of Long-Term Exposure in Low Environmental Concentrations of Antibiotics on the Growth and Development of Aquatica leii (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) from Transcription and Metabolism

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Materials

2.2. Antibiotics Treatment and Sample Collection

2.3. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity Assays

2.4. RNA Isolation and Transcriptome Sequencing

2.5. Transcriptome Assembly, DEG Screening, and Enrichment Analyses

2.6. Metabolite Extraction and Detection

2.7. Metabolome Analysis

2.8. Combination Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Influence of OTC and LEV on Growth, Development, and Physiology of A. leii

3.2. Transcriptomic Changes Under OTC and LEV Treatments of A. leii

3.3. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of the LEV and OTC-Responsive DEGs of A. leii

3.4. Differential Expression of Insect Hormone-Biosynthesis-Related Genes Under OTC and LEV Treatments

3.5. Overall Metabolomic Structure of A. leii Under OTC and LEV Treatments

3.6. Metabolomic Profiles of A. leii Under OTC and LEV Treatments

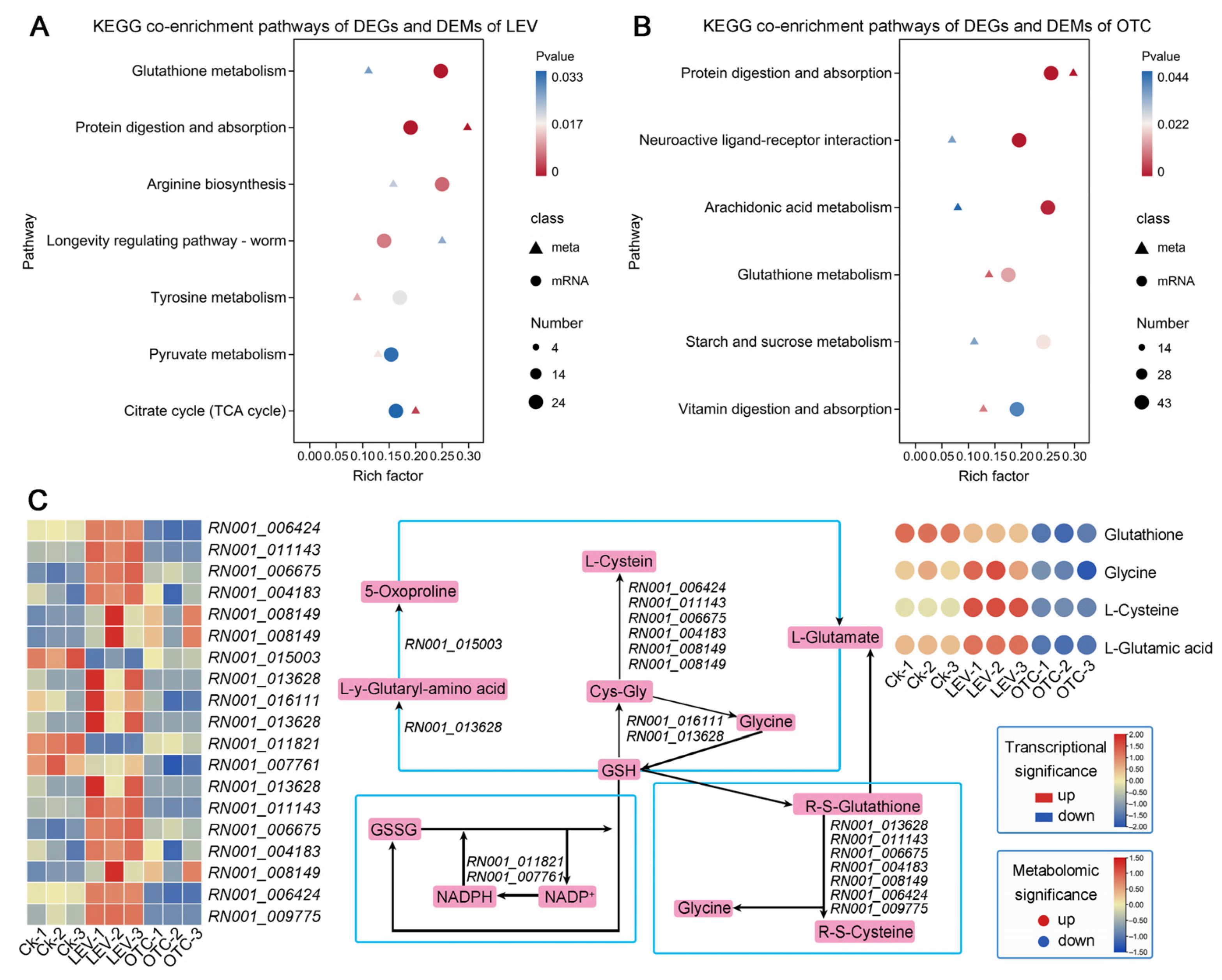

3.7. Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, X.; Zhu, X. Key homeobox transcription factors regulate the development of the firefly’s adult light organ and bioluminescence. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.M.; Cratsley, C.K. Flash signal evolution, mate choice, and predation in fireflies. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2008, 53, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.M.; Thancharoen, A.; Wong, C.H.; López-Palafox, T.; Santos, P.V.; Wu, C.; Reed, J.M. Firefly tourism: Advancing a global phenomenon toward a brighter future. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Faidi, M.A.; Tan, S.A.; Vijayanathan, J.; Malek, M.A.; Bahashim, B.; Isa, M.N.M. Fireflies in Southeast Asia: Knowledge gaps, entomotourism and conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2021, 30, 925–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.M.; Jusoh, W.F.A.; Walker, A.C.; Fallon, C.E.; Joyce, R.; Yiu, V. Illuminating firefly diversity: Trends, threats and conservation strategies. Insects 2024, 1, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Hernández, C.X.; Gutiérrez Mancillas, A.M.; Del-Val, E.; Mendoza-Cuenca, L. Living on the edge: Urban fireflies (Coleoptera, Lampyridae) in Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico. Peerj 2023, 11, e16622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, J.; Yan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Cao, C.; Wang, Y. Integrated mRNA and miRNA omics analyses reveal transcriptional regulation of the tolerance traits by Aquatica leii in response to high temperature. Insects 2025, 16, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepański, M.; Szajdak, L.W.; Meysner, T. Impact of shelterbelt and peatland barriers on agricultural landscape groundwater: Carbon and nitrogen compounds removal efficiency. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lihan, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Toh, S.C.; Leong, S.S. Plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistant Escherichia coli in Sarawak Rivers and aquaculture farms, Northwest of Borneo. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Salah, D.M.M.; Laffite, A.; Poté, J. Occurrence of bacterial markers and antibiotic resistance genes in Sub-Saharan rivers receiving animal farm wastewaters. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDDEP. The State of the World’s Antibiotics in 2021. Available online: https://onehealthtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/SOWA_01.02.2021_Low-Res.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Limbu, S.M.; Zhou, L.; Sun, S.X.; Zhang, M.L.; Du, Z.Y. Chronic exposure to low environmental concentrations and legal aquaculture doses of antibiotics cause systemic adverse effects in Nile tilapia and provoke differential human health risk. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotto, R.B.; Medriano, C.D.; Cho, Y.; Kim, H.; Chung, I.Y.; Seok, K.S.; Song, K.G.; Hong, S.W.; Park, Y.; Kim, S. Sub-lethal pharmaceutical hazard tracking in adult zebrafish using untargeted LC-MS environmental metabolomics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 339, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, D.P.; Ho, P.Y.; Huang, K.C. Modulation of antibiotic effects on microbial communities by resource competition. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, I.T.; Santos, L. Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: A review of the European scenario. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 736–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayani, M.U.R.; Yu, K.; Qiu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Gao, C.; Feng, R.; Zeng, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.; Su, H.L. Environmental concentrations of antibiotics alter the zebrafish gut microbiome structure and potential functions. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 278, 116760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Limbu, S.M.; Shen, M.; Zhai, W.; Qiao, F.; He, A.; Du, Z.Y.; Zhang, M. Environmental concentrations of antibiotics impair zebrafish gut health. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Takamatsu, D.; Harada, M.; Zendo, T.; Sekiya, Y.; Endo, A. Nisin A treatment to protect honey bee larvae from european foulbrood disease. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 3587–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Yin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Xu, X.; Shi, H. Abundance and dynamic distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in the environment surrounding a veterinary antibiotic manufacturing site. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yun, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. A review on the ecotoxicological effect of sulphonamides on aquatic organisms. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, T.; Li, M.; Mortimer, M.; Guo, L.H. Direct and gut microbiota-mediated toxicities of environmental antibiotics to fish and aquatic invertebrates. Chemosphere 2023, 329, 138692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, E.D.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; Islas-Flores, H.; Galar-Martínez, M. Developmental effects of amoxicillin at environmentally relevant concentration using zebrafish embryotoxicity test (ZET). Water Air Soil Poll. 2021, 232, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, C.; Liu, X.; Lee, S.; Kho, Y.; Kim, W.K.; Choi, K. Ecological risk assessment of amoxicillin, enrofloxacin, and neomycin: Are their current levels in the freshwater environment safe? Toxics 2021, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Li, F.; Mortimer, M.; Li, Z.; Peng, B.X.; Li, M.; Guo, L.H.; Zhuang, G. Antibiotics disrupt lipid metabolism in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae and 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Asselman, J.; Jeong, T.Y.; Yu, S.; De Schamphelaere, K.A.C.; Kim, S.D. Multigenerational effects of the antibiotic Tetracycline on transcriptional responses of Daphnia magna and its relationship to higher levels of biological organizations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12898–12907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, J.; Xin, Q. Effects of tetracycline on developmental toxicity and molecular responses in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Ecotoxicology 2015, 24, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.; Procaccianti, C.; Mignot, B.; Sadafi, H.; Schwenck, N.; Murgia, X.; Bianco, F. Deposition of inhaled Levofloxacin in cystic fibrosis lungs assessed by functional respiratory imaging. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, T.; Qian, H. Adverse effects of levofloxacin and oxytetracycline on aquatic microbial communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Guo, Z.; Hua, X. Antibiotics in water and sediments from Liao River in Jilin Province, China: Occurrence, distribution, and risk assessment. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Xu, X.R.; Zhou, G.J.; Liu, S.S.; Yue, W.Z.; Ying, G.G. Antibiotics in the coastal environment of the Hailing Bay region, South China Sea: Spatial distribution, source analysis and ecological risks. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 95, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, W.; Song, Z.; He, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, P.; Cheng, S. The Acute Toxicity and Cardiotoxic Effects of Levofloxacin on Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxics 2025, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Gandra, S.; Ashok, A.; Caudron, Q.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: An analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, W.; Liu, K.; Guo, Y.; Ding, C.; Han, J.; Li, P. Global review of macrolide antibiotics in the aquatic environment: Sources, occurrence, fate, ecotoxicity, and risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 439, 129628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Ahmed, W.; Mehmood, S.; Ou, W.; Li, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, L.; Mahmood, M.; Li, W. Evaluating the combined effects of Erythromycin and Levofloxacin on the growth of Navicula sp. and understanding the underlying mechanisms. Plants 2023, 12, 2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Korheina, D.K.A.; Fu, H.; Ge, X. Chronic exposure to dietary antibiotics affects intestinal health and antibiotic resistance gene abundance in oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense), and provokes human health risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, N.; Tamhankar, A.J.; Stålsby Lundborg, C. Antibiotic concentrations and antibiotic resistance in aquatic environments of the WHO Western Pacific and South–East Asia regions: A systematic review and probabilistic environmental hazard assessment. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e45–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, P.; Yu, Z.; Yang, L.; Ding, X.; Lv, H.; Yi, S.; Sheng, Q.; Zhang, L.; et al. Integrated microbiome and metabolome analyses reveal the effects of low pH on intestinal health and homeostasis of crayfish (Procambarus clarkii). Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 270, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Qi, M.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, W.; Yao, G.; Meng, Q.; Zheng, T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) livers reveals response mechanisms to high temperatures. Genes 2023, 14, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq—A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Want, E.J.; Masson, P.; Michopoulos, F.; Wilson, I.D.; Theodoridis, G.; Plumb, R.S.; Shockcor, J.; Loftus, N.; Holmes, E.; Nicholson, J.K. Global metabolic profiling of animal and human tissues via UPLC-MS. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alseekh, S.; Aharoni, A.; Brotman, Y.; Contrepois, K.; D’Auria, J.; Ewald, J.; Ewald, J.C.; Fraser, P.D.; Giavalisco, P.; Hall, R.D.; et al. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics: A guide for annotation, quantification and best reporting practices. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: Data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Bu, Y.; Li, L. Integrated transcriptome and metabolome analysis of Rice leaves response to high Saline-Alkali stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griboff, J.; Carrizo, J.C.; Bacchetta, C.; Rossi, A.; Wunderlin, D.A.; Cazenave, J.; Amé, M.V. Effects of short-term dietary oxytetracycline treatment in the farmed fish Piaractus mesopotamicus. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2025, 44, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Limbu, S.M.; Qiao, F.; Du, Z.Y.; Zhang, M. Influence of long-term feeding antibiotics on the gut health of Zebrafish. Zebrafish 2018, 15, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wan, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z. Transcriptome and microbiome analyses of the mechanisms underlying antibiotic-mediated inhibition of larval development of the saprophagous insect Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 2021, 223, 112602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xia, X.; Zhao, S.; Shi, M.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y. The physiological and toxicological effects of antibiotics on an interspecies insect model. Chemosphere 2020, 248, 126019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhou, F.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Zhong, X.; Lv, H.; Yi, S.; Gao, Q.; Yang, Z.; et al. Integrated comparative transcriptome and weighted gene co-expression network analysis provide valuable insights into the response mechanisms of crayfi38sh (Procambarus clarkii) to copper stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Li, H.W.; Dong, Z.X.; Yang, X.J.; Lin, L.B.; Chen, J.Y.; Yuan, M.L. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) to explore the molecular adaptations to fresh water. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 2676–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Guo, J.; Deng, X.Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, J.Y.; Lin, L.B. Comparative transcriptomic analysis provides insights into the response to the benzo(a)pyrene stress in aquatic firefly (Luciola leii). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 661, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Jin, Z.; Liao, X.; Feng, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, H. Nano-Silicon mitigates Sulfamethoxazole-induced stress in Wheat seedlings: Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 119896, 2213–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, R.; Yu, X.; Fan, J. Physiological, biochemical and transcriptional responses of cyanobacteria to environmentally relevant concentrations of a typical antibiotic-roxithromycin. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 152703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhao, H. Transcriptomic analysis of hepatotoxicology of adult Zebrafish (Danio rerio) exposed to environmentally relevant Oxytetracycline. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 82, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Takahashi, F.; Bak, S.M.; Kanda, K.; Iwata, H. Effects of exposure to oxytetracycline on the liver proteome of red seabream (Pagrus major) in a real administration scenario. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 256, 109325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma, K.; Kaneko, Y. Hormonal regulation of insect metamorphosis with special reference to juvenile hormone biosynthesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2013, 103, 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, K.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, W.; Ge, W.; Feng, Q.; Palli, S.R.; Li, S. Antagonistic actions of juvenile hormone and 20-hydroxyecdysone within the ring gland determine developmental transitions in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, Q.; Mo, J.; Tian, Y.; Iwata, H.; Song, J. Transcriptomic alterations in Water Flea (Daphnia magna) following pravastatin treatments: Insect hormone biosynthesis and energy metabolism. Toxics 2022, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izadi, H. Endocrine and enzymatic shifts during insect diapause: A review of regulatory mechanisms. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1544198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, M.; Zimmermann, M.; Claassen, M.; Sauer, U. Nontargeted metabolomics reveals the multilevel response to antibiotic perturbations. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 1214–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slominski, A.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Pawelek, J. L-tyrosine and L-dihydroxyphenylalanine as hormone-like regulators of melanocyte functions. Pigm. Cell Melanoma Res. 2012, 25, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, A.; Maekawa, M.; Nakagawa, K. L-Tyrosine enhances tight junction integrity and anti-inflammatory properties: A potential alternative to antibiotic growth promoters in broilers. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Ahmed, S.T.; Kim, Y.J.; Mun, H.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Yang, C.J. Effect of sea tangle (Laminaria japonica) and charcoal supplementation as alternatives to antibiotics on growth performance and meat quality of Ducks. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 27, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yang, S.; Ka, W.; Gao, P.; Li, Y.; Long, R.; Wang, J. Association of gut microbiota with metabolism in Rainbow Trout under acute heat stress. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 846336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; Antunes, S.C.; Correia, A.T.; Nunes, B. Oxytetracycline effects in specific biochemical pathways of detoxification, neurotransmission and energy production in Oncorhynchus mykiss. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 164, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Lin, J.; Liu, C.; Yan, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Lv, H.; Cao, C.; Wang, Y. Unraveling the Impacts of Long-Term Exposure in Low Environmental Concentrations of Antibiotics on the Growth and Development of Aquatica leii (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) from Transcription and Metabolism. Insects 2025, 16, 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121239

Li J, Lin J, Liu C, Yan L, Wang Q, Zhou Z, Lv H, Cao C, Wang Y. Unraveling the Impacts of Long-Term Exposure in Low Environmental Concentrations of Antibiotics on the Growth and Development of Aquatica leii (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) from Transcription and Metabolism. Insects. 2025; 16(12):1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121239

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jiapeng, Jiani Lin, Chao Liu, Lihong Yan, Qimeng Wang, Zitong Zhou, He Lv, Chengquan Cao, and Yiping Wang. 2025. "Unraveling the Impacts of Long-Term Exposure in Low Environmental Concentrations of Antibiotics on the Growth and Development of Aquatica leii (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) from Transcription and Metabolism" Insects 16, no. 12: 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121239

APA StyleLi, J., Lin, J., Liu, C., Yan, L., Wang, Q., Zhou, Z., Lv, H., Cao, C., & Wang, Y. (2025). Unraveling the Impacts of Long-Term Exposure in Low Environmental Concentrations of Antibiotics on the Growth and Development of Aquatica leii (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) from Transcription and Metabolism. Insects, 16(12), 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121239