Chromosome Comparisons of Australian Scaptodrosophila Species

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Species Examined

2.2. Polytene Chromosome Squashes

2.3. Cerebral Ganglion Chromosome Spreads

2.4. C-Banding

2.5. NOR Silver Staining

2.6. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

3. Results

3.1. Lacto-Acetic Orcein Staining

3.2. C-Banding

3.3. NOR Location

4. Discussion

4.1. C-Banding

4.2. NOR Location

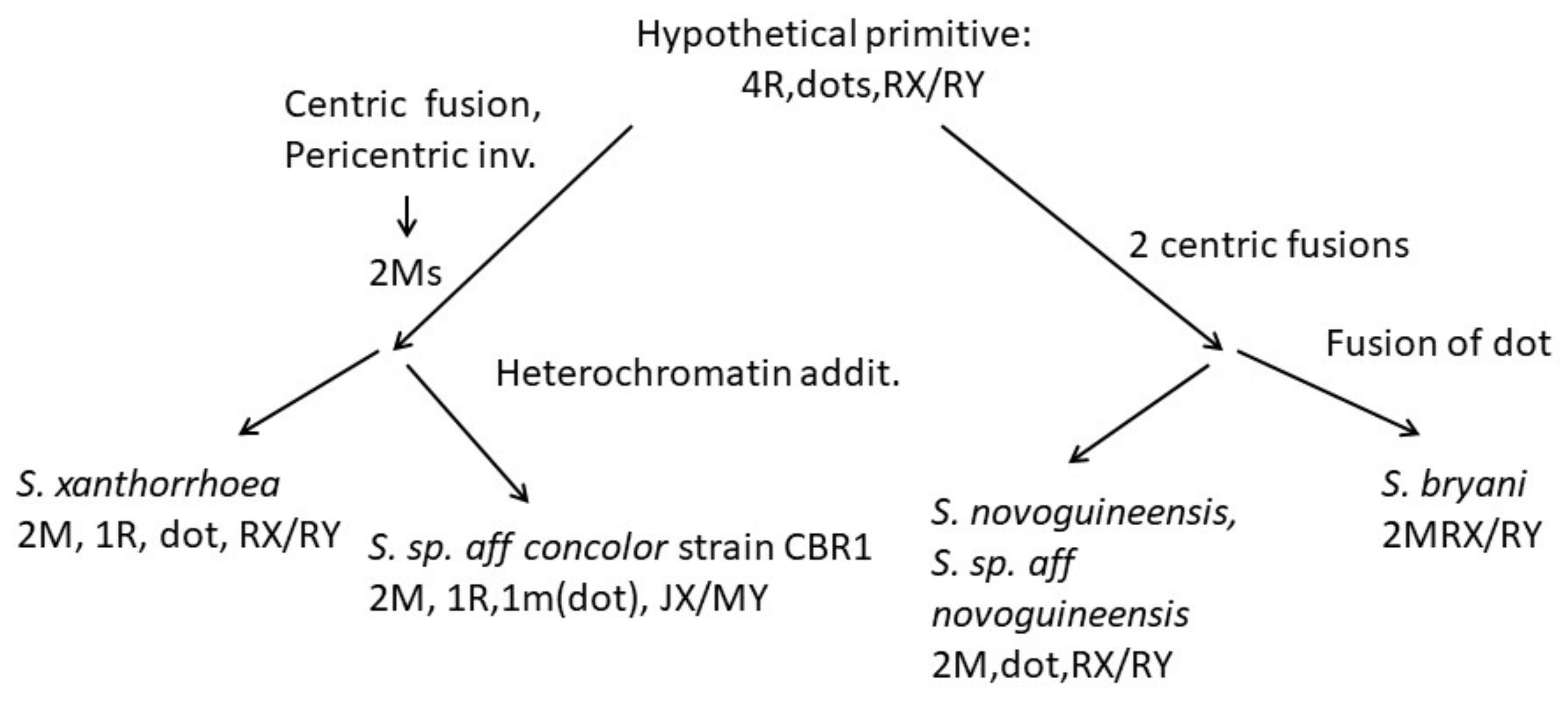

4.3. Karyotype Evolution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russo, C.A.M.; Mello, B.; Franzao, A.; Voloch, C.M. Phylogenetic analysis and a time tree for a large drosophilid data set (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2013, 169, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, W.B. The genus Drosophila (Diptera) in Eastern Queensland. 2. Seasonal changes in a natural population 1952–1953. Aust. J. Zool. 1956, 4, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, W.B. The genus Drosophila (Diptera) in Eastern Queensland. 3. Cytological evolution. Aust. J. Zool. 1956, 4, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, D.A. A phylogenetic revised classification of genera in the Drosophilidae (Diptera) 187. Bull. ANMH 1990, 197, 1–141. [Google Scholar]

- DeSalle, R. The phylogenetic relationships of flies in the family Drosophilidae deduced from mtDNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1992, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, I.R.; Parsons, P.A. Adaptive radiation in the Subgenus Scaptodrosophila of Australian Drosophila. Nature 1975, 258, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvey, S.F.; Barker, J.S.F. Scaptodrosophila aclinata: A new hibiscus flower-breeding species related to S. hibisci (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Rec. Aust. Mus. 2001, 53, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, I.R.; Parsons, P.A. The subgenus Scaptodrosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Syst. Entomol. 1978, 3, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, I.R.; Parsons, P.A. Culture methods for species of the Drosophila (Scaptodrosophila) coracina group. Dros. Inf. Serv. 1980, 55, 147–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, I.R. Drosophilidae (Insecta: Diptera) in the Cooktown area of North Queensland. Aust. J. Zool. 1984, 32, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, I.R. The chromosomes of six species of the Drosophila lativittata complex. Aust. J. Zool. 1984, 32, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.C.C.; Sunnucks, P.; Bedo, D.G.; Barker, J.F.S. Microsatellites reveal male recombination and neo-sex chromosome formation in Scaptodrosophila hibisci (Drosophilidae). Genet. Res. 2006, 87, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.A.; Jackson, M.; Bock, I.R. Contrasting resource utilization in two Australian species of Drosophila Fallen (Diptera) feeding on the Bracken Fern Pteridium scopoli. Aust. J. Entomol. 1982, 21, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedo, D.G.C. Q and H banding in the analysis of Y chromosome rearrangements in Lucilia cuprina (Weidemann) (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Chromosoma 1980, 77, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, W.M.; Black, D.A. Controlled silver staining of nucleolus organizer regions with a protective colloidal developer: A 1-step method. Experientia 1980, 36, 11014–11015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirino, M.G.; Rossi, L.F.; Bressa, M.J.; Luaces, J.P.; Merani, M.S. Comparative study of mitotic chromosomes in two blowflies, Lucilia sericata and L. cluvia (Diptera, Calliphoridae), by C- and G-like banding patterns and rRNA loci, and implications for karyotype evolution. Comp. Cytogenet. 2015, 9, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ploton, D.; Menager, M.; Jeannesson, P.; Himber, G.; Pigeon, F.; Adnet, J.J. Improvement in the staining and in the visualization of the argyophilic proteins of the nucleolar organizer region at the optical level. Histochem. J. 1986, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzbasioglu, D.; Unal, F. Karyotyping and NOR banding of Allium sativum L. (Liliaceae) cultivated in Turkey. Pak. J. Bot. 2004, 36, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lomholt, B.E.; Toft, J.M. The effect of pH on silver staining of nucleolus organizer regions. Stain. Technol. 1987, 62, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.R.; Ellison, J.R. Silver staining for nucleolar organizer regions of vertebrate chromosomes. Stain. Technol. 1983, 58, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olert, J.; Sawatzki, G.; Kling, G.H.; Gebauer, J. Cytological and histochemical studies on the mechanism of the selective silver staining of nucleolus organizer regions (NORs). Histochemistry 1979, 60, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, L.E. Improvements in the silver staining technique for nucleolar organizer regions (AgNOR). J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1993, 41, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bilinski, S.M.; Bilinska, B. A new version of the Ag-NOR technique. A combination with DAPI staining. Histochem. J. 1996, 28, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, V.P.; Borges, A.R.; Fernandes, M.A. NOR sites detected by Ag-DAPI staining of an unusual autosome chromosome of Bradysia hygida (Diptera: Sciaridae) colocalize with C-banded heterochromatic region. Genetica 2002, 114, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavalcco, K.F.; Pazza, R. A rapid alternative technique for obtaining silver-positive patterns in chromosomes. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004, 27, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roiha, H.; Miller, R.J.; Woods, L.C.; Glover, D.M. Arrangements and rearrangements of sequences flanking the two types of rDNA insertion in D. melanogaster. Nature 1981, 290, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, A.J.; Gorab, E.; Amabis, J.M.; Lara, F.J.S. A molecular cytogenetic comparison between Rhynchosciara americana and Rhynchosciara hollaenderi (Diptera, Sciaridae). Genome 1993, 36, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madalena, C.R.G.; Amabis, J.M.; Stocker, A.J.; Gorab, E. The localization of ribosomal DNA in Sciaridae (Diptera: Nematocera) reassessed. Chromosome Res. 2007, 15, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Stollar, B.D. Comparison of poly (A)-poly(dT) and poly(I)-poly(dC) as immu- nogens for the induction of antibodies to RNA/DNA hybrids. Mol. Immunol. 1982, 19, 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- Gorab, E.; Amabis, J.M.; Stocker, A.J.; Drummond, L.; Stollar, B.D. Potential sites of triple-helical nucleic acid formation in chromosomes of Rhynchosciara americana and Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosome Res. 2009, 17, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.J.D.; Dennis, E.S.; Honeycutt, R.I.; Contreras, N.; Peacock, W.J. Cytogenetics of the parthenogenetic grasshopper Warramaba virgo and its bisexual relatives. Chromosoma 1982, 85, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedo, D.G. Polytene and mitotic chromosome analysis in Ceratis capitana (Diptera; Tephritidae. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 1986, 28, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmquist, G. The mechanism of C-banding: Depurination and β-elimination. Chromosoma 1979, 72, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddle, N.C.; Elgin, S.C.R. The Drosophila dot chromosome: Where genes flourish amidst repeats. Genetics 2018, 210, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roy, V.; Monti-Dedieu, L.; Chaminade, N.; Siljak-Yakovlev, S.; Aulard, S.; Lemeunier, F.; Montchamp-Moreau, C. Evolution of the chromosomal location of rDNA genes in two Drosophila species subgroups: Ananassae and melanogaster. Heredity 2005, 94, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKee, B.D.; Karpen, G.H. Drosophila ribosomal RNA genes function as an X-Y pairing site during male meiosis. Cell 1990, 61, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, B.D.; Habera, L.; Vrana, J.A. Evidence that intergenic spacer repeats of Drosophila melanogaster rRNA genes function as X-Y pairing sites in male meiosis, and a general model for achiasmatic pairing. Genetics 1992, 132, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, W.; Link, B.; Leoncini, O. The location of the nucleolar organizer regions in Drosophila hydei. Chromosoma 1975, 51, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, H.J. Bearings of the ‘Drosophila’ work on systematics. In The New Systematics; Huxley, J., Ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1940; pp. 185–268. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, W.D.; Bishop, J.G.; Carson, H.L.; Frank, M.B. Location of the 18/28S ribosomal RNA genes in two Hawaiian Drosophila species by monoclonal immunological identification of RNA/DNA hybrids in situ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 3751–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sturtevant, A.H.; Novitski, E. The homologies of the chromosome elements in the genus Drosophila. Genetics 1941, 26, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, S.W.; Bhutkar, A.; McAllister, B.F.; Matsuda, M.; Matzkin, L.M.; O’Grady, P.M.; Rohde, C.; Valente, V.L.; Aguadé, M.; Anderson, W.W.; et al. Polytene chromosomal maps of 11 Drosophila species: The order of genomic scaffolds inferred from genetic and physical maps. Genetics 2008, 179, 1601–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krivshenko, J.D. A cytogenetic study of the X chromosome of Drosophila busckii and its relation to phylogeny. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1955, 41, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krivshenko, J.D. New evidence for the homology of the short euchromatic elements oof the X and Y chromosomes of Drosophila busckii with the microchromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 1959, 44, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaceit, M.; Juan, E. Fate of the dot chromosome genes in Drosophila willistoni and Scaptodrosophila lebanonensis determined by in situ hybridization. Chromosome Res. 1998, 6, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicoso, B.; Bachtrog, D. Reversal of an ancient sex chromosome to an autosome in Drosophila. Nature 2013, 499, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pita, S.; Yanina, P.; Lucia da Silva Valente, V.; das Gracas Silva de Melo, Z.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, A.C.L.; Montes, M.A.; Rohde, C. Cytogenetic mapping of the Muller F element genes in Drosophila willistoni group. Genetica 2014, 142, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craddock, E.M.; Gall, G.J.; Jonas, M. Hawaiian Drosophila genomes: Size variation and evolutionary expansions. Genetica 2016, 144, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, F.E. Published karyotypes of the Drosophilidae. Drosoph. Inf. Serv. 1998, 81, 5–125. [Google Scholar]

- Van Klinken, R.D. Taxonomy and distribution of the coracina group of Scaptodrosophila (Duda: Drosophilidae) in Australia. Invertebr. Syst. 1997, 11, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Species Group | Collection Site |

|---|---|---|

| Scaptodrosophila cancellata | coracina | Lake Placid, Qld (September 2011) |

| Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. cancellata | coracina | Lake Placid, Qld (April 2012) |

| Scaptodrosophila claytoni | coracina | Nowra, NSW (March 2014) |

| Scaptodrosophila evanescens | coracina | Nowra, NSW (March 2014) |

| Scaptodrosophila specensis | coracina | Lake Placid, Qld (April 2012) |

| Scaptodrosophila lativittata * | coracina | Melbourne, Vic (March 2021) |

| Scaptodrosophila nitidithorax | coracina | South Perth, WA (February 2021) |

| S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 | barkeri? | Townsville, Qld (September 2011) |

| S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 | barkeri? | Lake Placid, Qld (September 2011) |

| Scaptodrosophila xanthorrhoeae | Lake Placid, Qld (September 2011) | |

| Scaptodrosophila novoguineensis | Mossman, Qld (May 2011) | |

| Scaptodrosophila sp. aff. novoguineensis | Lake Placid, Qld (April 2013) | |

| Scaptodrosophila bryani | bryani | Lake Placid, Qld (May 2011) |

| Species | Chromosomes Examined | Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Scaptodrosophila cancellata | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. sp aff cancellata | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. claytoni | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, rDNA FISH (female) |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. evanescens | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. specensis | ganglion | C-banding |

| polytene | not done | |

| S. lativittata | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, NOR from satellites |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. nitidithorax * | polytene | squash preparation |

| S. sp. aff concolor strain CBN17 | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding, |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. sp. aff concolor strain CBR1 | ganglion | orcein staining |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. xanthorrhoeae | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. novoguineensis | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding |

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. sp. aff novoguineensis | ganglion | orcein staining, C-banding |

| rDNA FISH | ||

| polytene | squash preparation | |

| S. bryani | ganglion | orcein staining |

| polytene | squash preparation |

| Species | Female Brain | Male Brain | Total Chromosomes, Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. cancellata | 1M3R1mDJX | 1M3R1mDJXRY | 6 pairs = 9 arms |

| S. sp. aff. cancellata | 5R1mDJX | 5R1mDJXmY | 7 pairs = 9 arms |

| S. claytoni | 1M3R1DRX | 1M3R1DRXRY | 6 pairs = 7arms |

| S. evanescens | 1M3R1DRX | 1M3R1DRXRY | 6 pairs = 7arms |

| S. specensis | 1M3R1DRX | 1M3R1DRXRY | 6 pairs = 7arms |

| S. lativittata | 1M3R1mDRX | 1M3R1mDRXRY | 6 pairs = 8 arms |

| S. nitidithorax * | 1M3R1JDRX | 1M3R1JDRXRY | 6 pairs = 8 arms |

| S. enigma * | 1M3R1MDJX | 1M3R1MDJXJY | 6 pairs = 9 arms |

| S. howensis * | 1M3R1MDJX | 1M3R1MDJXJY | 6 pairs = 9 arms |

| S. novamaculosa * | 1M3R1JDJX | 1M3R1JDJXRY | 6 pairs = 9 arms |

| S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBN17 | 1M3R1DJX | 1M3R1DJXRY | 6 pairs = 8 arms |

| S. sp. aff. concolor strain CBR1 | 2M1R1mDJX | 2M1R1mDJXMY | 5 pairs = 9 arms |

| S. xanthorrhoeae | 2M1R1DRX | 2M1R1DRXRY | 5 pairs = 7 arms |

| S. novoguineensis | 2M1DRX | 2M1DRXRY | 4 pairs = 6 arms |

| S. sp. aff. novoguineensis | 2M1DRX | 2M1DRXRY | 4 pairs = 6 arms |

| S. bryani | 2MRX | 2MRXRY | 3 pairs = 5 arms |

| S. hibisci# | 1M3m1J1D $ | 1M3m1J1D $ | 6 pairs = 10 arms |

| Characteristic | Observations in Drosophila | Observations in Scaptodrosophila |

|---|---|---|

| Link to ancestral karyotype | Yes | Not observed |

| Heterochromatin location | Centromeres, ‘dots’, Y, some arms | As for Drosophila |

| NORs | X, Y usually, dot, occasionally others | X, Y, dot |

| Dots | Size varies, heterochromatic but C-banding variable, usually present in polytene set | Size varies, heterochromatic but C-banding variable, usually absent in polytene set |

| Mitotic chromosomes | A–F arms, syntenic | A–F arms, assumed |

| Polytene chromosomes | Generally spread well | Spread poorly, weak points, repeats |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stocker, A.J.; Schiffer, M.; Gorab, E.; Hoffmann, A. Chromosome Comparisons of Australian Scaptodrosophila Species. Insects 2022, 13, 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13040364

Stocker AJ, Schiffer M, Gorab E, Hoffmann A. Chromosome Comparisons of Australian Scaptodrosophila Species. Insects. 2022; 13(4):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13040364

Chicago/Turabian StyleStocker, Ann Jacob, Michele Schiffer, Eduardo Gorab, and Ary Hoffmann. 2022. "Chromosome Comparisons of Australian Scaptodrosophila Species" Insects 13, no. 4: 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13040364

APA StyleStocker, A. J., Schiffer, M., Gorab, E., & Hoffmann, A. (2022). Chromosome Comparisons of Australian Scaptodrosophila Species. Insects, 13(4), 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13040364