Erosive Wear Behavior of Fiberglass-Reinforced Epoxy Laminate Composites Modified with SiO2 Nanoparticles Fabricated by Resin Infusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

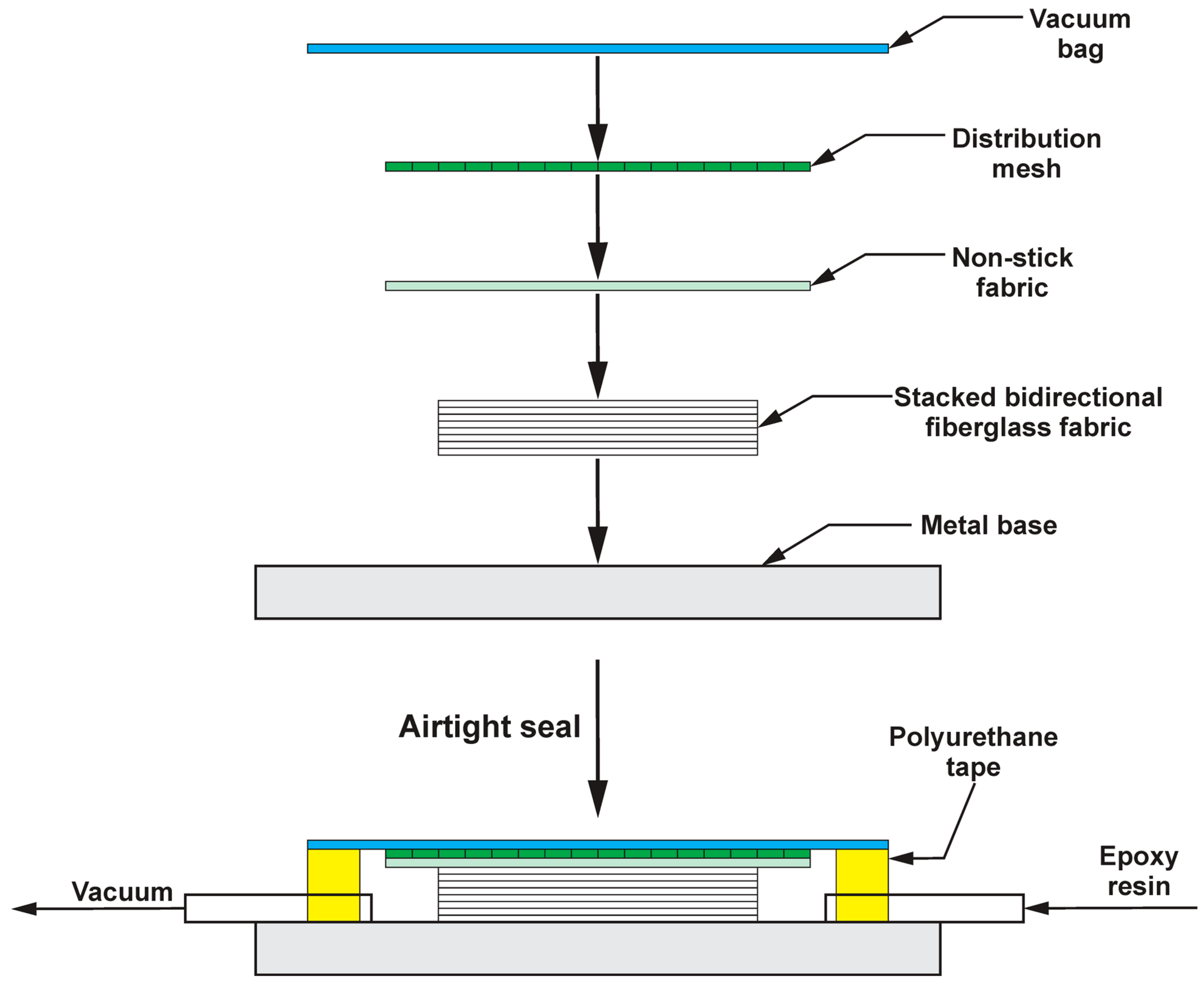

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Incorporation of SiO2 NPs

2.3. Erosive Particle

2.4. Characterization

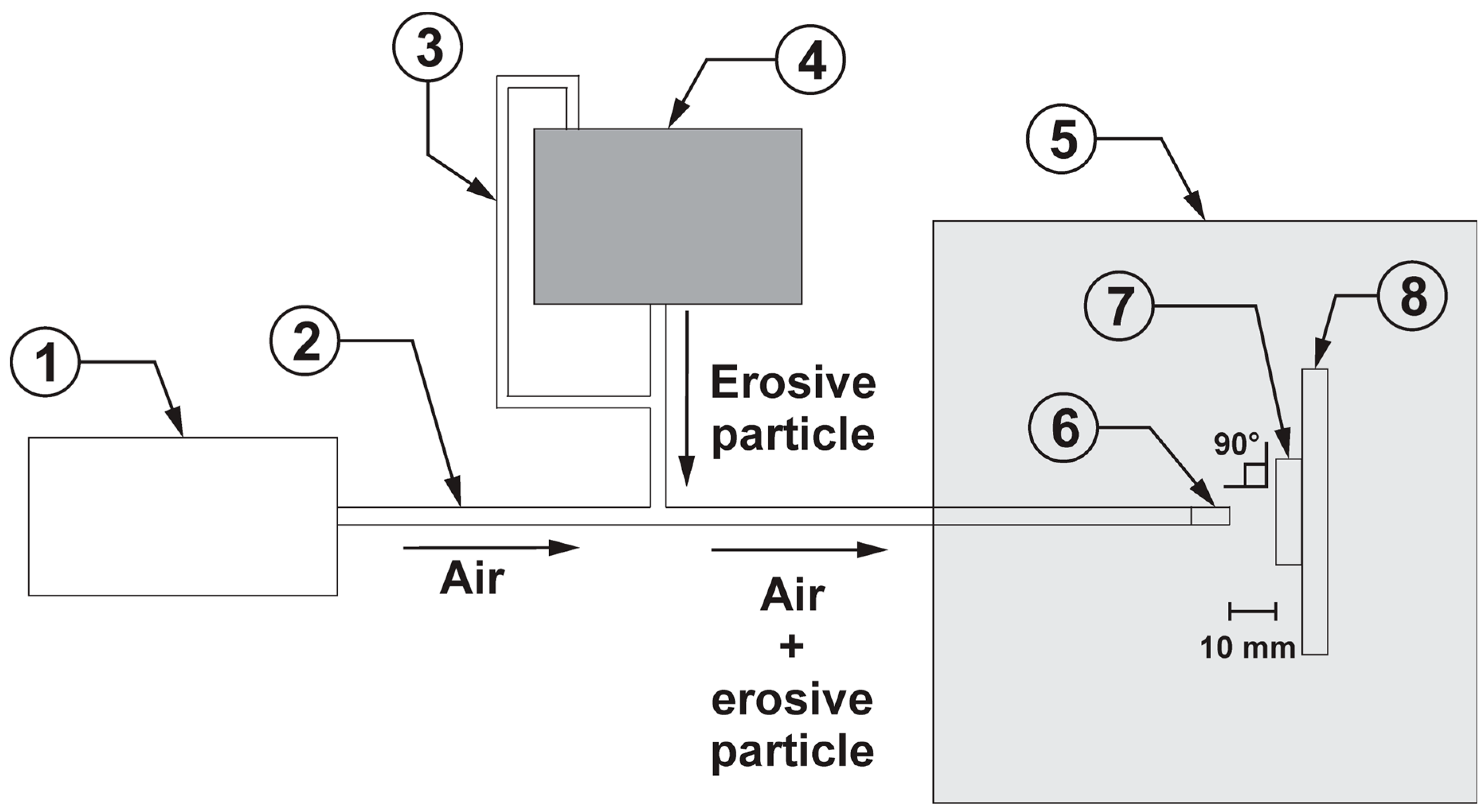

2.5. Erosive Wear Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Roughness, Hardness, and Modulus of Elasticity

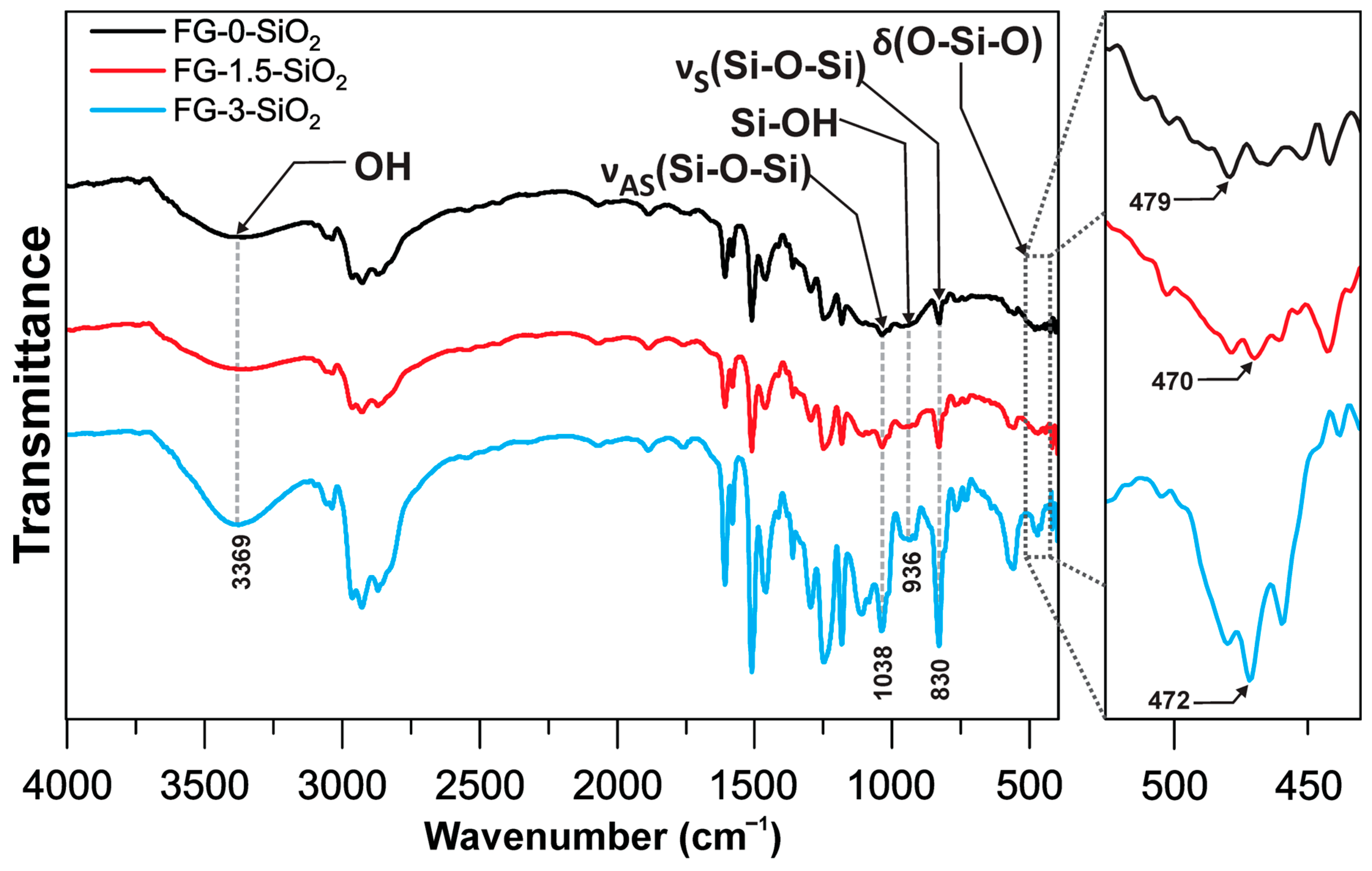

3.2. FTIR

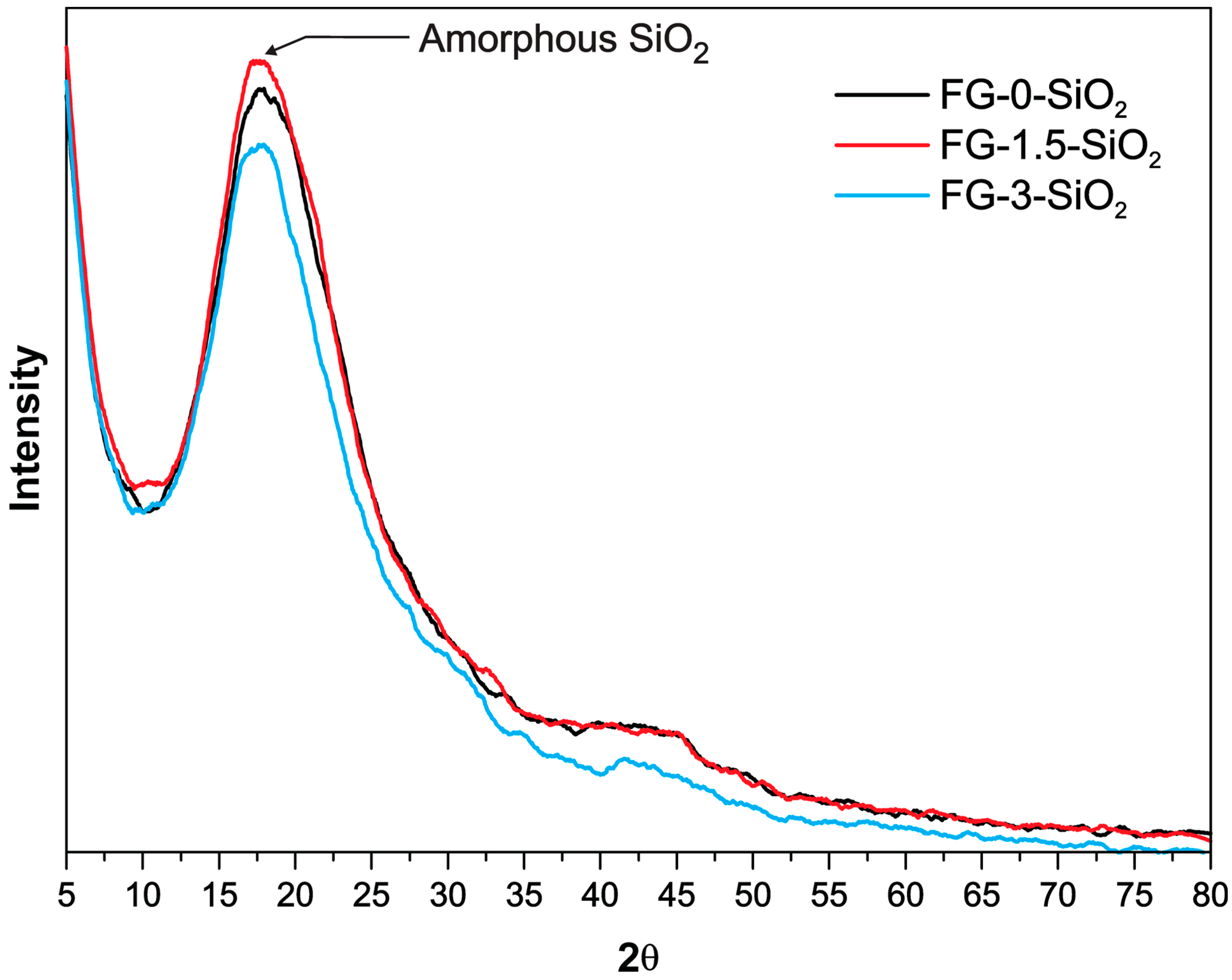

3.3. GIXRD

3.4. Topographic Analysis

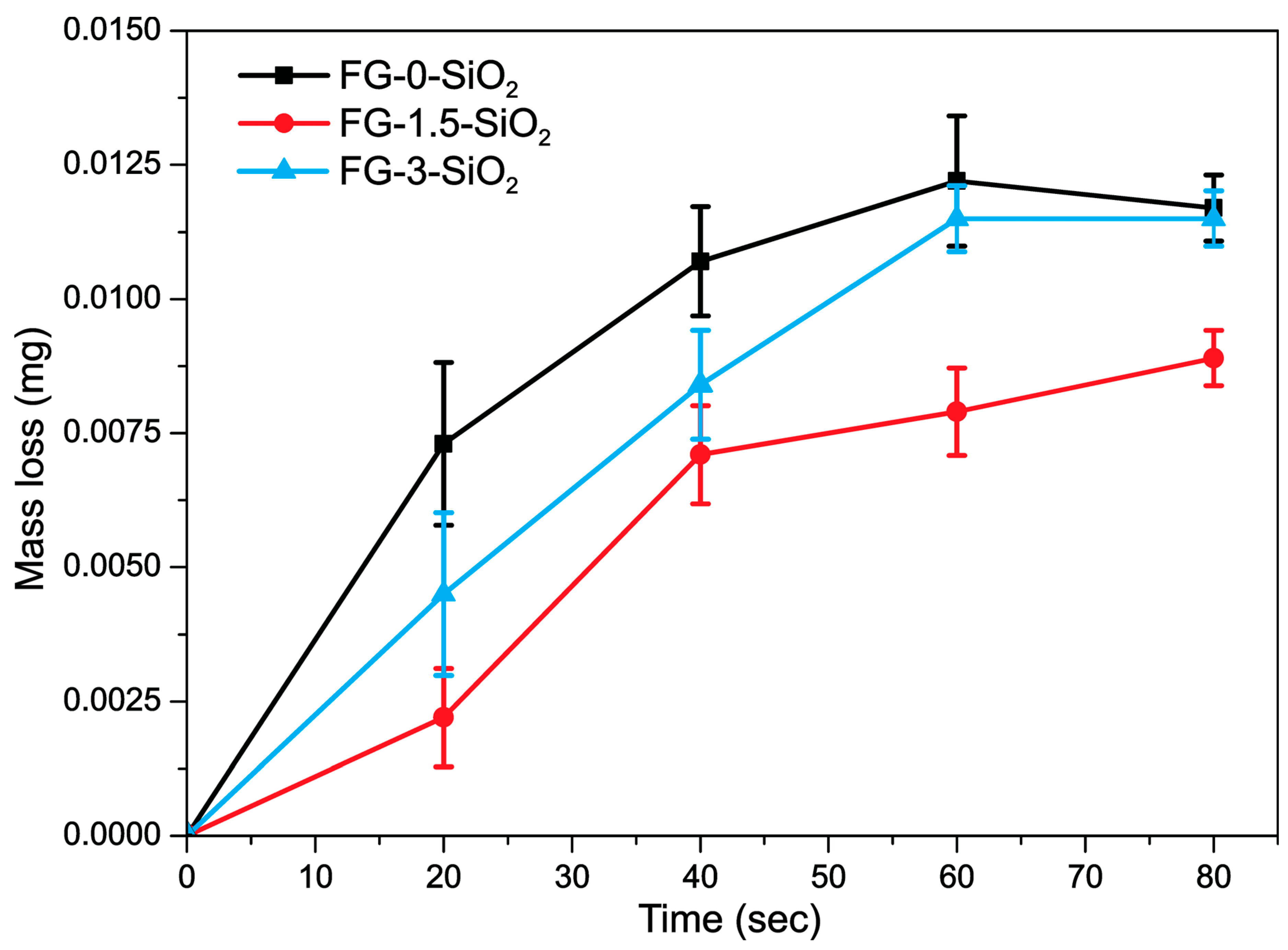

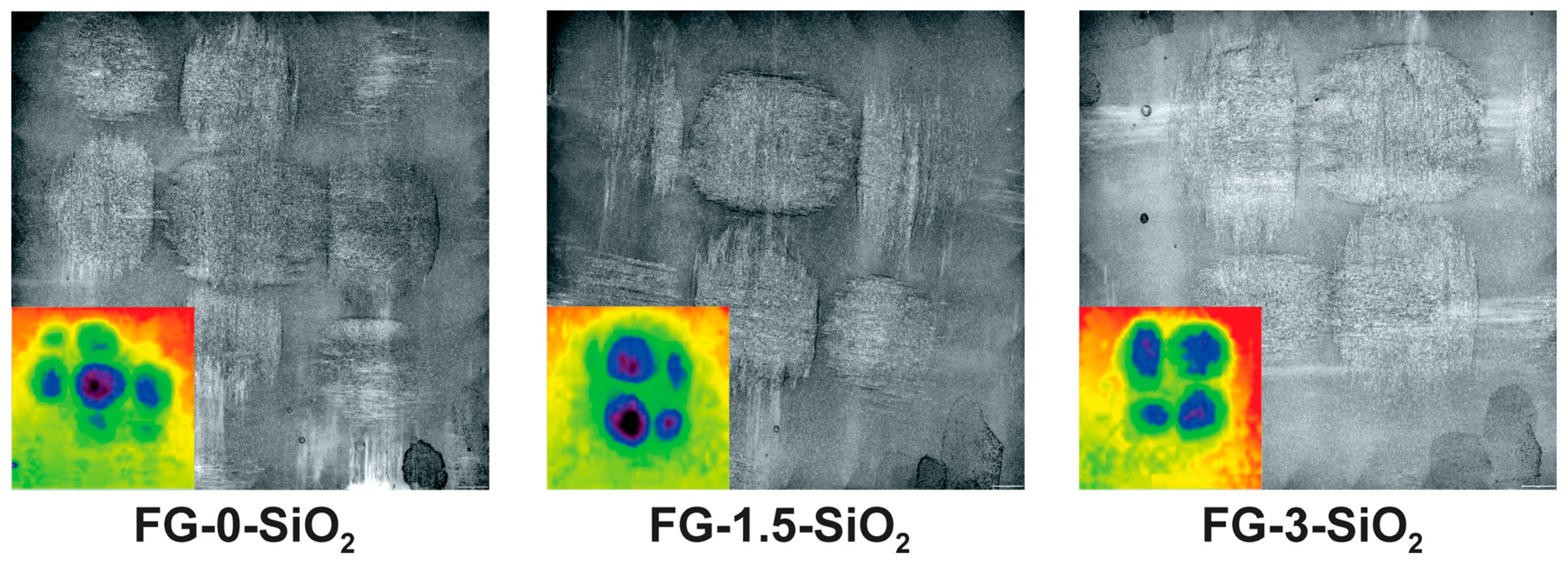

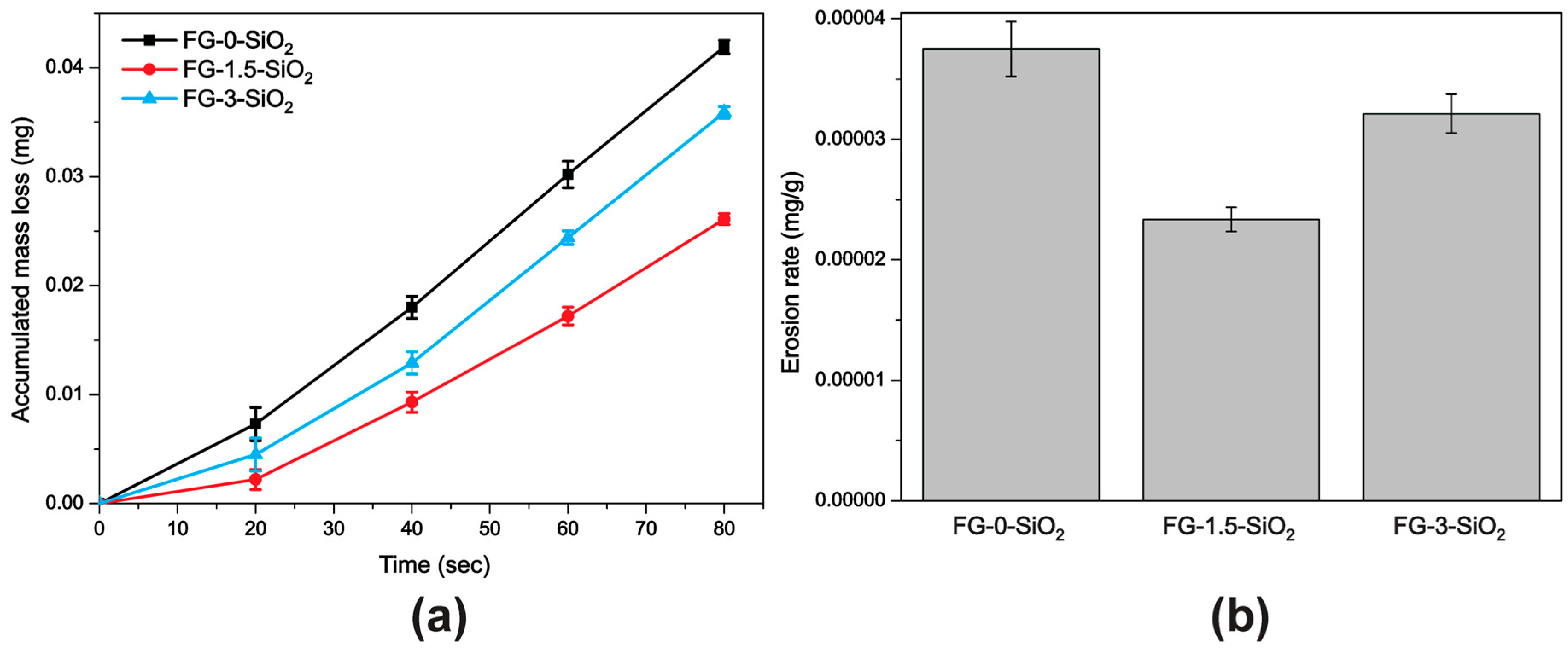

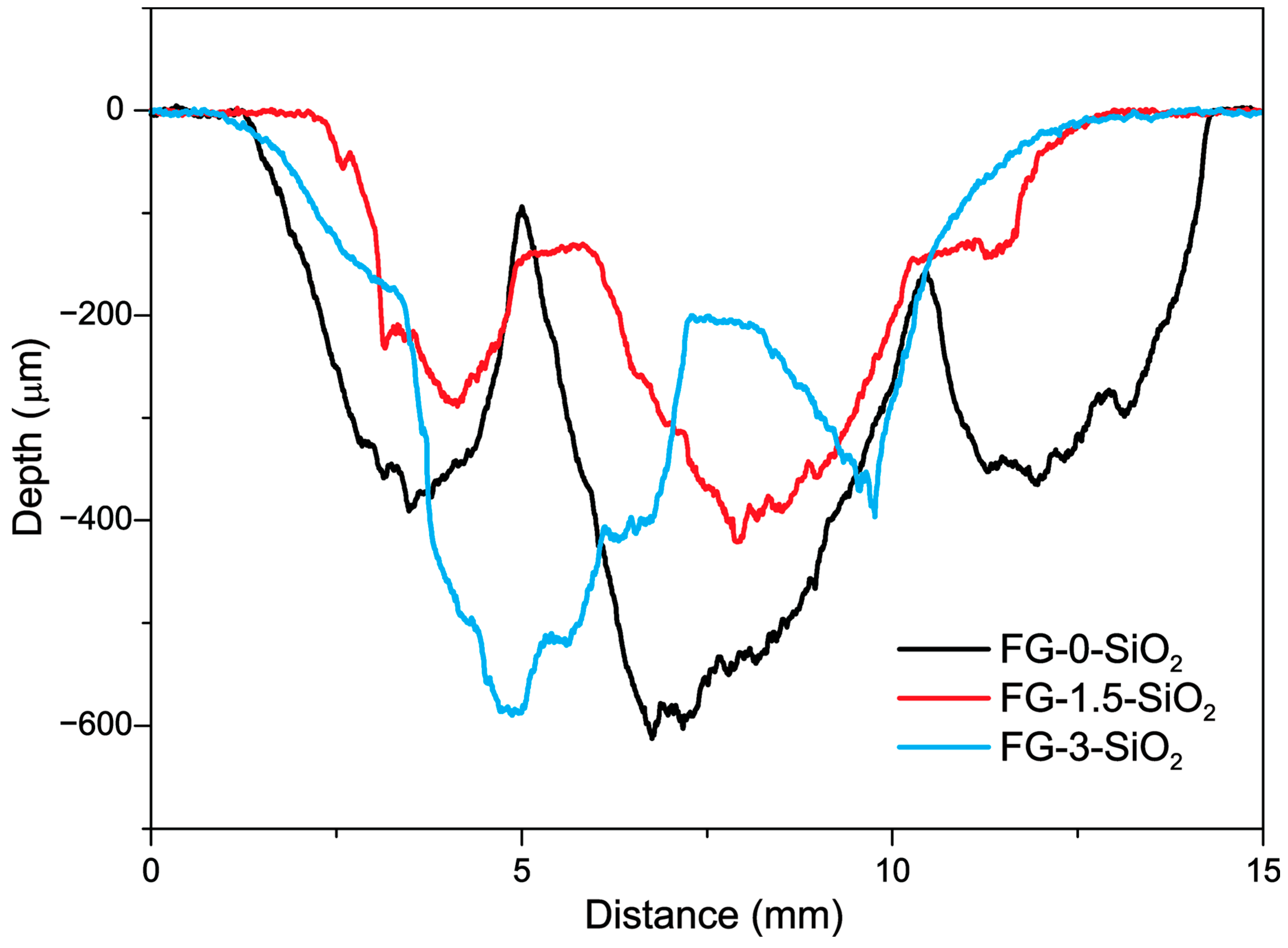

3.5. Mass Loss, Profilometry, and Erosion Rate

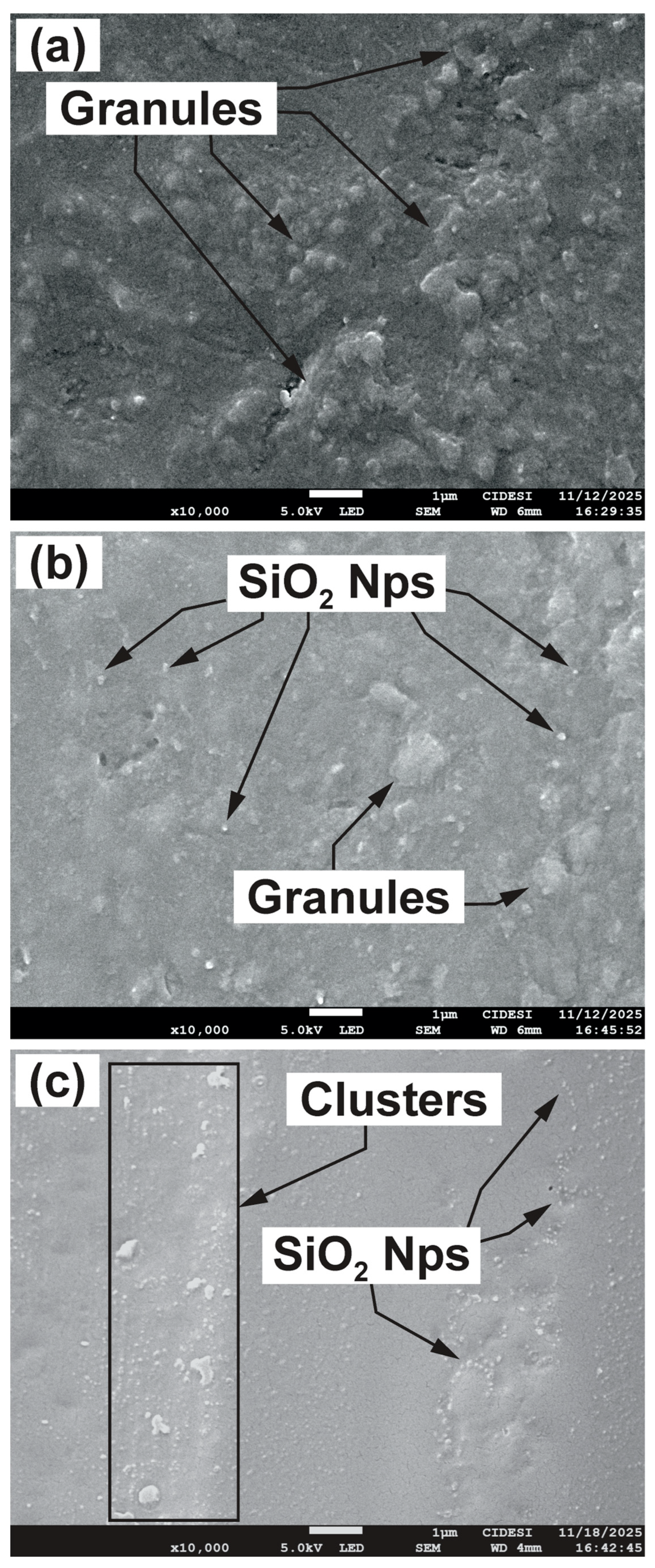

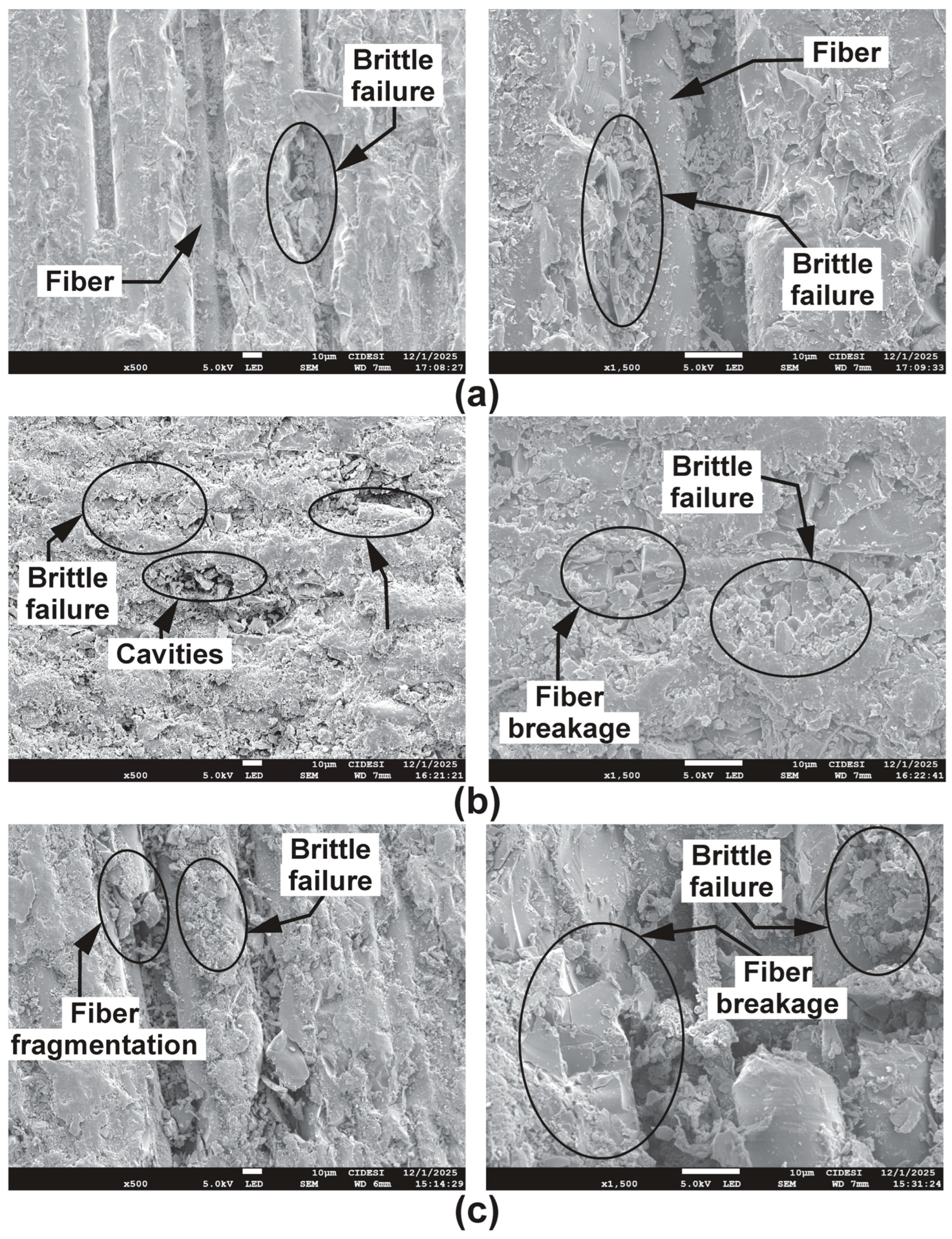

3.6. Wear Mechanisms

3.7. Economic and Industrial Feasibility Considerations

4. Conclusions

- The incorporation of SiO2 NPs into the epoxy matrix of fiberglass-reinforced laminated composites improves the resistance to erosive wear, but this effect depends directly on the concentration and homogeneous dispersion of the NPs.

- An optimal concentration of 1.5 wt.% of SiO2 NPs, combined with an ultrasonic dispersion and degassing process, allows for a homogeneous distribution of the NPs within the epoxy matrix. This generates a more uniform surface, increases hardness and the elastic modulus, and strengthens the interface between the matrix and the fiber.

- The improvement in mechanical and tribological properties observed in the FG-1.5-SiO2 composite is attributed to the well-dispersed NPs, which act as barriers to microcrack propagation, improve stress transfer, and dissipate impact energy during the erosion process.

- An excessive concentration of nanoparticles, such as the 3.0 wt.% concentration found in FG-3-SiO2, causes agglomeration of NPs. This compromises the properties of the laminated composite by creating structural defects, reducing the effective interfacial area, and the NPs act as stress concentration points, resulting in behavior similar to that of the laminated composite without NPs.

- The results of this study demonstrate that there is an optimal concentration of SiO2 NPs to significantly improve erosion resistance in laminated epoxy matrix and fiberglass composites. This provides valuable information for the design of laminated composites modified with NPs intended for structural applications in environments subject to wear from solid particles, where surface integrity and service life are critical.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Georgantzinos, S.K.; Giannopoulos, G.I.; Stamoulis, K.; Markolefas, S. Composites in Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering. Materials 2023, 16, 7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Academic research for composite aerostructures—A personal perspective. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 273, 111239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, I.; Grandi, S.; Solazzi, L. Implementation of Composite Materials for an Industrial Vehicle Component: A Design Approach. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzepieciński, T.; Batu, T.; Kibrete, F.; Lemu, H.G. Application of Composite Materials for Energy Generation Devices. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanto, S.; Rio Prabowo, A.; Adiputra, R.; Ehlers, S.; Braun, M.; Yaningsih, I.; Istanto, I.; Wijaya, R. A review of composite materials for marine purposes: Historical perspective and current state. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2025, 72, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Shanmugam, V.; Palani, G.; Marimuthu, U.; Veerasimman, A.; Korniejenko, K.; Oliinyk, I.; Trilaksana, H.; Sundaram, V. Investigation on Erosion Resistance in Polyester–Jute Composites with Red Mud Particulate: Impact of Fibre Treatment and Particulate Addition. Polymers 2024, 16, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Cao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, J.; Xing, J.; Zhang, C. Damage mechanism and residual tensile strength of CFRP laminates subjected to high-velocity sand erosion. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 300, 112459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A.; Satapathy, A.; Chand, N.; Barkoula, N.M.; Biswas, S. Solid particle erosion wear characteristics of fiber and particulate filled polymer composites: A review. Wear 2010, 268, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domun, N.; Hadavinia, H.; Zhang, T.; Sainsbury, T.; Liaghat, G.H.; Vahid, S. Improving the fracture toughness and the strength of epoxy using nanomaterials—A review of the current status. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 10294–10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiremath, A.; Murthy, A.A.; Thipperudrappa, S. KNB Nanoparticles Filled Polymer Nanocomposites: A Technological Review. Cogent Eng. 2021, 8, 1991229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, Y.; Fasihi, M.; Rhee, K.Y. Efficiency of stress transfer between polymer matrix and nanoplatelets in clay/polymer nanocomposites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 143, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Ali, S.; Ali, K.; Ullah, S.; Ismail, P.M.; Humayun, M.; Zeng, C. Impact of the nanoparticle incorporation in enhancing mechanical properties of polymers. Results Eng. 2025, 24, 106151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Khan, K.H.; Parvez, M.M.H.; Irizarry, N.; Uddin, M.N. Polymer Nanocomposites with Optimized Nanoparticle Dispersion and Enhanced Functionalities for Industrial Applications. Processes 2025, 13, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Samad, U.A.; Anis, A.; Alam, M.; Ubaidullah, M.; Al-Zahrani, S.M. Effects of SiO2 and ZnO Nanoparticles on Epoxy Coatings and Its Performance Investigation Using Thermal and Nanoindentation Technique. Polymers 2021, 13, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zubaydi, A.S.J.; Salih, R.M.; Al-Dabbagh, B.M. Effect of nano TiO2 particles on the properties of carbon fiber-epoxy composites. Prog. Rubber Plast. Recycl. Technol. 2021, 37, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrgari, D.; Moztarzadeh, F.; Sabbagh-Alvani, A.A.; Rasoulianboroujeni, M.; Tahriri, M.; Tayebi, L. Mechanical properties and tribological performance of epoxy/Al2O3 nanocomposite. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 1220–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.; Younis, M.; Ismail, M.; Nassar, E. Improved Wear-Resistant Performance of Epoxy Resin Composites Using Ceramic Particles. Polymers 2022, 14, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuanga, W.; Geng-sheng, J.; Lei, P.; Bao-lin, Z.; Ke-zhi, L.; Jun-long, W. Influences of surface modification of nano-silica by silane coupling agents on the thermal and frictional properties of cyanate ester resin. Results Phys. 2018, 9, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govea Paz, L.I.; Martínez Pérez, A.I.; Vera Cárdenas, E.E.; Moreno Ríos, M.; González Carmona, J.M. Study of erosion wear by solid particle of a PMMA/SiO2 hybrid coating with graphene oxide applied on a composite laminate. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2024, 38, 2570–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, M.T. Low velocity impact and fracture characterization of SiO2 nanoparticles filled basalt fiber reinforced composite tubes. J. Compos. Mater. 2020, 54, 3415–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragosta, G.; Abbate, M.; Musto, P.; Scarinzi, G.; Mascia, L. Epoxy-silica particulate nanocomposites: Chemical interactions, reinforcement and fracture toughness. Polymer 2005, 46, 10506–10516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, J.; Silva, A.; Tornero, J.A.; Gámez, J.; Salán, N. Void Content Minimization in Vacuum Infusion (VI) via Effective Degassing. Polymers 2021, 13, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Zou, X.; Gong, Y.; Guo, H. An Enhanced Vacuum-Assisted Resin Transfer Molding Process and Its Pressure Effect on Resin Infusion Behavior and Composite Material Performance. Polymers 2024, 16, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanny, K.; Mohan, T.P. Resin infusion analysis of nanoclay filled glass fiber laminates. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 58, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwa, M.; Youssef, S.M.; Ali-Eldin, S.S.; Megahed, M. Integrated vacuum assisted resin infusion and resin transfer molding technique for manufacturing of nano-filled glass fiber reinforced epoxy composite. J. Ind. Text. 2020, 51, 5113S–5144S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oosterom, S.; Allen, T.; Battley, M.; Bickerton, S. An objective comparison of common vacuum assisted resin infusion processes. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 125, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera Cárdenas, E.E.; Oropeza Pérez, F.I.; Rubio González, C.; Martínez Pérez, A.I. Wear and friction behavior of composite materials reinforced with carbon fiber and Kevlar. J. Compos. Mater. 2025, 60, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslava Hernández, A.; Vera Cárdenas, E.E.; Martínez Pérez, A.I.; Rodríguez González, J.; Rubio González, C. Impact of the aging process in composite materials under solid particle impact wear. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2025, 0, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinke, A.P.; Carnicer, A.; Govoreanu, R.; Scheltjens, G.; Lauwerysen, L.; Mertens, N.; Vanhoutte, K.; Brewster, M.E. Particle shape and orientation in laser diffraction and static image analysis size distribution analysis of micrometer sized rectangular particles. Powder Technol. 2008, 186, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.E.; Behnsen, J.; Duller, R.A.; Nichols, T.E.; Worden, R.H. Particle size analysis: A comparison of laboratory-based techniques and their application to geoscience. Sediment. Geol. 2024, 464, 106607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billones, R.G.; Tackx, M.L.M.; Flachier, A.T.; Zhu, L.; Daro, M.H. Image analysis as a tool for measuring particulate matter concentrations and gut content, body size, and clearance rates of estuarine copepods: Validation and application. J. Mar. Syst. 1999, 22, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard G76-95; Standard Test Method for Conducting Erosion Tests by Solid Particle Impingement Using Gas Jets1. Annual Book of ASTM Standards: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1995.

- Khare, J.M.; Dahiya, S.; Gangil, B.; Ranakoti, L.; Sharma, S.; Huzaifah, M.R.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Dwivedi, S.P.; Chattopadhyaya, S.; Kilinc, H.C.; et al. Comparative analysis of erosive wear behaviour of epoxy, polyester and vinyl esters based thermosetting polymer composites for human prosthetic applications using Taguchi design. Polymers 2021, 13, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsha, A.P.; Sanjeev, K.J. Erosive wear studies of epoxy-based composites at normal incidence. Wear 2008, 265, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.; Zhang, N.; Huang, M.; Shen, C.; Castro, J.; Tan, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, C. The remarkably enhanced particle erosion resistance and toughness properties of glass fiber/epoxy composites via thermoplastic polyurethane nonwoven fabric. Polym. Test. 2018, 69, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xijing, L.; Yong, C. Effect of SiO2 nanoparticles on the hardness and corrosion resistance of NiW/SiO2 nano composite coating prepared by electrodeposition. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golshokouh, M.A.; Refahati, N.; Saffari, P.R. Effect of Silicon Nanoparticles on Moisture Absorption and Fracture Toughness of Polymethyl Methacrylate Matrix Nanocomposites. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousry Zaghloul, M.M.; Fuseini, M.; Yousry Zaghloul, M.M. Review of epoxy nano-filled hybrid nanocomposite coatings for tribological applications. FlatChem 2025, 49, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontou, E.; Christopoulos, A.; Koralli, P.; Mouzakis, D.E. The Effect of Silica Particle Size on the Mechanical Enhancement of Polymer Nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Lv, Q.; Chen, S.; Li, C.; Sun, S.; Hu, S. Effect of Interfacial Bonding on Interphase Properties in SiO2/Epoxy Nanocomposite: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 7499–7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, Y. Study of nanoparticles aggregation/agglomeration in polymer particulate nanocomposites by mechanical properties. Compos. Part A 2016, 84, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, R.; Stein, M.; Schaller, J. Comparing amorphous silica, short-range-ordered silicates and silicic acid species by FTIR. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oufakir, A.; Khouchaf, L.; Elaatmani, M.; Zegzouti, A.; Louarn, G.; Ben Fraj, A. Study of structural short order and surface changes of SiO2 compounds. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 149, 01041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.; Datta, A. Synthesis of SiO2-Nanoparticles from Rice Husk Ash and its Comparison with Commercial Amorphous Silica through Material Characterization. Silicon 2021, 13, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, R.H.; Stein, M.; Schaller, J. Comparing silicon mineral species of different crystallinity using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Front. Environ. Chem. 2024, 5, 1462678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praseptiangga, D.; Zahara, H.L.; Widjanarko, P.I.; Joni, I.M.; Panatarani, C. Preparation and FTIR spectroscopic studies of SiO2-ZnO nanoparticles suspension for the development of carrageenan-based bio-nanocomposite film. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2219, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Zhuang, Q.; Huang, G.; Deng, H.; Zhang, X. Infrared Spectrum Characteristics and Quantification of OH Groups in Coal. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 17064–17076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Soud, A.; Daradkeh, S.I.; Knápek, A.; Holcman, V.; Sobola, D. Electrical characteristics of different concentration of silica nanoparticles embedded in epoxy resin. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 125520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farman, A.; Nisar, A.; Madiha, A.; Amir, S.; Shah, S.S.; Bilal, M. Epoxy Polyamide Composites Reinforced with Silica Nanorods: Fabrication, Thermal and Morphological Investigations. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 3869–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Wu, Z.; Lin, J.; Wang, F.; Li, P.; Xu, R.; Yang, M.; Han, L.; Zhang, D. A rapid analytical method for the specific surface area of amorphous SiO2 based on X-Ray diffraction. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 531, 119841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouchaf, L.; Boulahya, K.; Das, P.P.; Nicolopoulos, S.; Kis, V.K.; Lábár, J.L. Study of the Microstructure of Amorphous Silica Nanostructures Using High-Resolution Electron Microscopy, Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy, X-ray Powder Diffraction, and Electron Pair Distribution Function. Materials 2020, 13, 4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.; Begam, N.; Basu, J.K. Dispersion of polymer grafted nanoparticles in polymer nanocomposite films: Insights from surface x-ray scattering and microscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 222203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulkar, S.R.; Pawar, N.R. Synthesis of SiO2 Nanoparticles by Using Sol Gel Method. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2025, 12, 510–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.A.; Shyla, J.M.; Xavier, F.P. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2/SiO2 nano composites for solar cell applications. Appl. Nanosci. 2012, 2, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo Villarreal, N.; Gandara Martínez, E.; García Méndez, M.; Gracia Pinilla, M.; Guzmán Hernández, A.M.; Castaño, V.M.; Gómez Rodríguez, C. Synthesis and Characterization of SiO2 Nanoparticles for Application as Nanoadsorbent to Clean Wastewater. Coatings 2024, 14, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; Trifkovic, M.; Ponnurangam, S. Surface Functionalization-Induced Effects on Nanoparticle Dispersion and Associated Changes in the Thermophysical Properties of Polymer Nanocomposites. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 3962–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Velázquez, A.R.; Velasco-Soto, M.A.; Pérez-García, S.A.; Licea-Jiménez, L. Functionalization Effect on Polymer Nanocomposite Coatings Based on TiO2–SiO2 Nanoparticles with Superhydrophilic Properties. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Laminated Composite | Concentration of SiO2 NPs (wt.%) |

|---|---|

| FG-0-SiO2 | 0.0 |

| FG-1.5-SiO2 | 1.5 |

| FG-3-SiO2 | 3.0 |

| Laminated Composite | Ra (μm) | SD (μm) | Hardness (HV) | SD (HV) | E (GPa) | SD (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG-0-SiO2 | 0.684 | 0.188 | 19.84 | 0.059 | 9.912 | 0.120 |

| FG-1.5-SiO2 | 0.215 | 0.020 | 35.58 | 0.496 | 19.66 | 2.549 |

| FG-3-SiO2 | 0.475 | 0.230 | 13.83 | 0.208 | 5.491 | 0.052 |

| Laminated Composite | Erosion Rate (mg/g) | SD (mg/g) | Total Mass Loss (mg) | SD (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG-0-SiO2 | 3.7501 × 10−5 | 2.279 × 10−6 | 0.0419 | 0.0006 |

| FG-1.5-SiO2 | 2.3360 × 10−5 | 1.007 × 10−6 | 0.0261 | 0.0005 |

| FG-3-SiO2 | 3.2131 × 10−5 | 1.621 × 10−6 | 0.0359 | 0.0005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alvarez Lozano, A.S.; Martínez Pérez, A.I.; Vera Cárdenas, E.E.; González Carmona, J.M.; Mendoza Galván, A. Erosive Wear Behavior of Fiberglass-Reinforced Epoxy Laminate Composites Modified with SiO2 Nanoparticles Fabricated by Resin Infusion. Lubricants 2026, 14, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14020065

Alvarez Lozano AS, Martínez Pérez AI, Vera Cárdenas EE, González Carmona JM, Mendoza Galván A. Erosive Wear Behavior of Fiberglass-Reinforced Epoxy Laminate Composites Modified with SiO2 Nanoparticles Fabricated by Resin Infusion. Lubricants. 2026; 14(2):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14020065

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlvarez Lozano, Angel Sebastian, Armando Irvin Martínez Pérez, Edgar Ernesto Vera Cárdenas, Juan Manuel González Carmona, and Arturo Mendoza Galván. 2026. "Erosive Wear Behavior of Fiberglass-Reinforced Epoxy Laminate Composites Modified with SiO2 Nanoparticles Fabricated by Resin Infusion" Lubricants 14, no. 2: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14020065

APA StyleAlvarez Lozano, A. S., Martínez Pérez, A. I., Vera Cárdenas, E. E., González Carmona, J. M., & Mendoza Galván, A. (2026). Erosive Wear Behavior of Fiberglass-Reinforced Epoxy Laminate Composites Modified with SiO2 Nanoparticles Fabricated by Resin Infusion. Lubricants, 14(2), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants14020065