3.1. Structural Study of PMA

PMA-2 is a dispersive viscosity index improver with poor shear stability and is claimed to have a modified structure. Taking into account representativeness and typicality, this paper uses PMA-2 as an example to detail the structural research process of PMA.

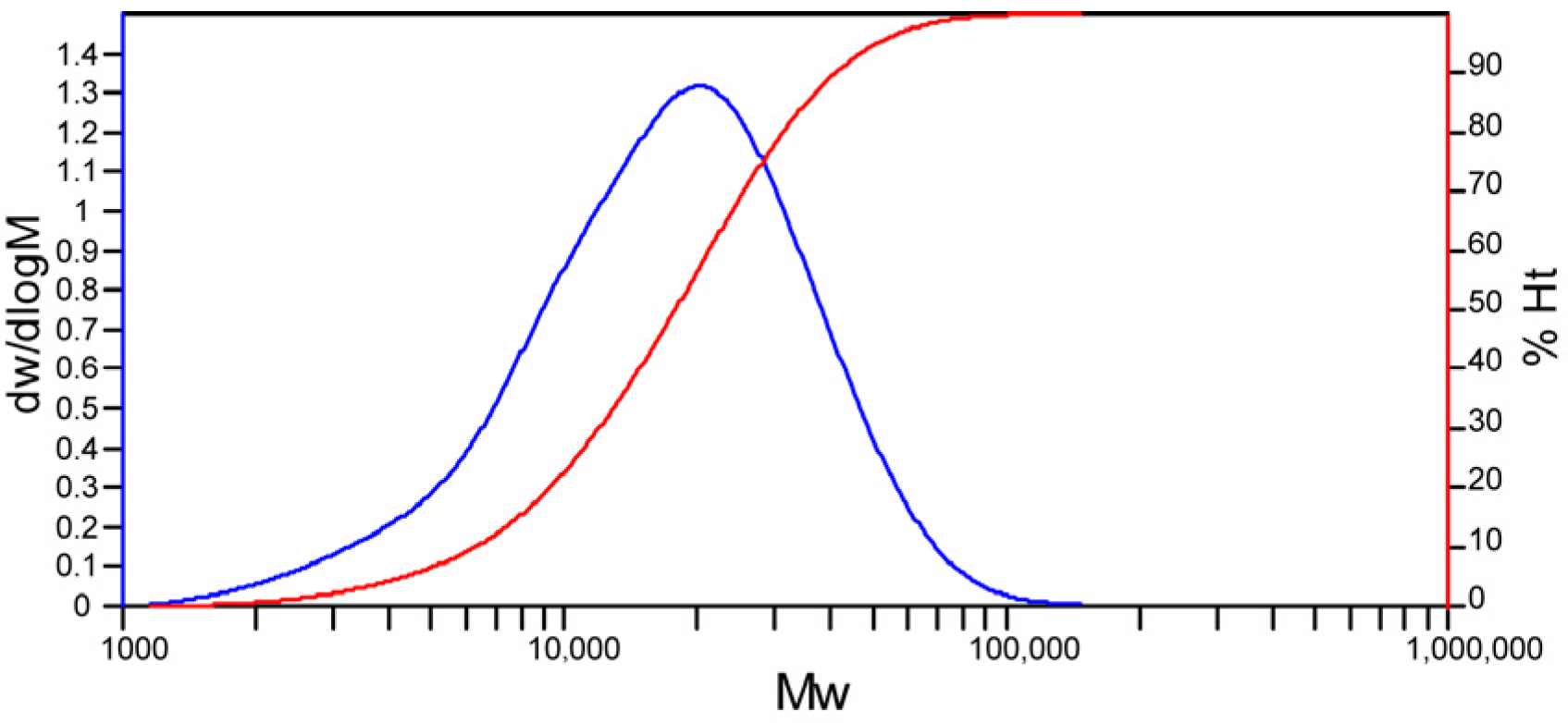

Firstly, GPC characterization was employed to determine the molecular weight and molecular weight distribution of PMA. In addition to the PMA component, solvent oil information was also observed. The distribution plot of PMA-2 main component is shown in

Figure 1. The specific results for PMA-2 are shown in

Table 4. The original GPC report is contained in

Supplementary Materials.

In

Table 4, PDI = Mw/Mn. The ideal monodisperse system has a PDI of 1, but the actual synthetic products all have a PDI greater than 1. The closer the PDI value is to 1, the narrower the molecular weight distribution of the polymer, meaning the molecular weights are relatively uniform; a PDI value greater than 1 indicates a wider molecular weight distribution, meaning there are molecules of different molecular weights within the polymer.

Based on molecular weight and monomer composition data, the average molecular weight of monomers and the degree of polymerization (DP) of each PMA can be further calculated by the following formulas.

In this formula,

is the average molecular weight of the monomers in PMA molecules,

is the molecular weight of each monomer,

is the content of each monomer. And

, so

In this formula, DPw is the weight-average degree of polymerization of each PMA, and Mw is the weight-average molecular weight of each PMA.

Secondly, organic elemental analysis of PMA was conducted, as shown in

Table 5.

Table 5 reveals that PMA-2 contains a little nitrogen in addition to minor sulfur (maybe catalyst or initiator residues).

Subsequently, GC-MS analysis was conducted to determine the approximate content of small molecular structures such as unpolymerized monomers and free alcohols in PMA. GC-MS analysis of the PMA-2 sample after chloroform extraction revealed the presence of information on N-methylacrylamide (NMA), dodecyl methacrylate, tetradecyl methacrylate, hexadecyl methacrylate, and octadecyl methacrylate. This aligns with the nitrogen detected in the OEA of PMA-2, indicating its source is NMA. This suggests NMA serves as a modified structure, enhancing the dispersibility of PMA-2. The original GC-MS data is contained in the

Supplementary Materials.

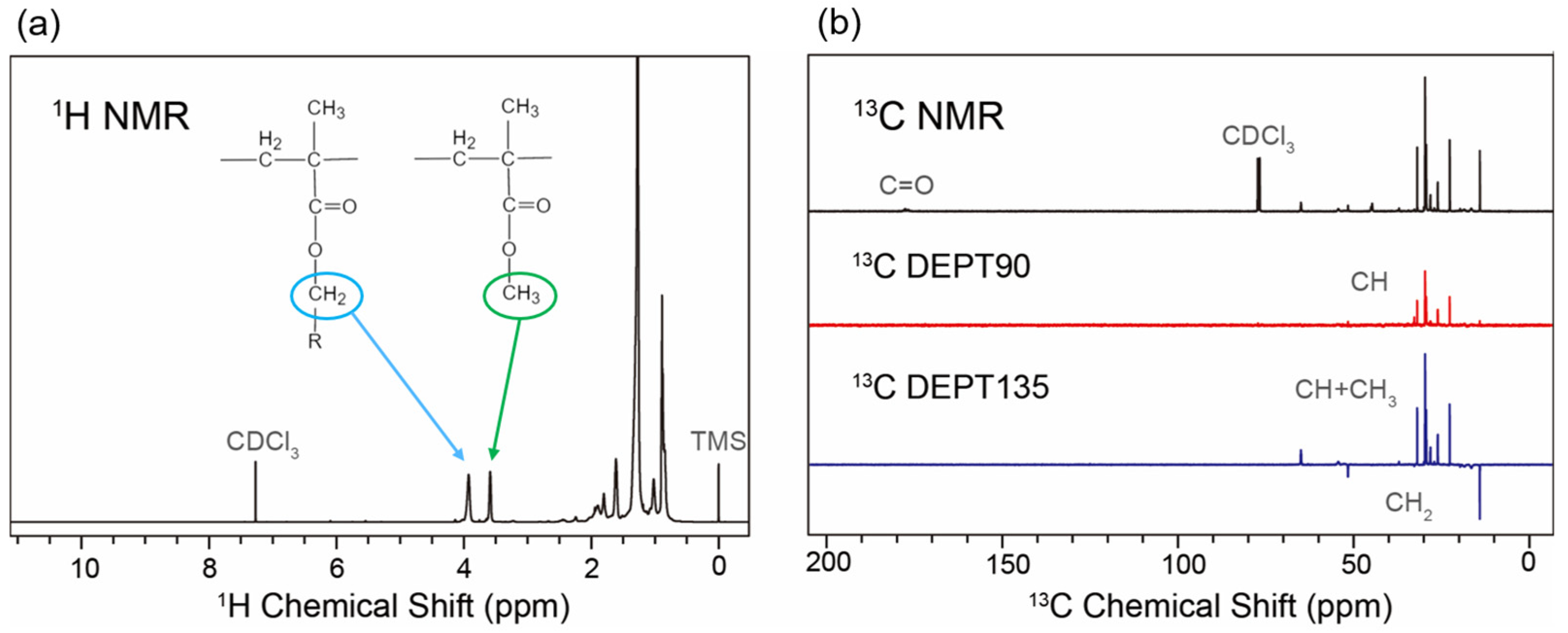

Furthermore, quantitative studies were conducted using NMR and pyrolysis GC-MS methods. PMA-2 was quantitatively characterized via

1H and

13C NMR spectra. The DEPT (Distortionless Enhancement by Polarization Transfer) spectrum enabled the distinction between primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary carbons, thereby allowing assessment of the degree of carbon chain branching.

Figure 2 presents the

1H and

13C NMR spectra of PMA-2.

In the 1H spectrum of PMA-2, two distinct peaks at approximately 3.6 ppm and 3.9 ppm correspond to methyl methacrylate and longer-chain fatty alcohol methacrylates, respectively. Quantitative analysis of the hydrogen spectrum reveals the quantitative relationships between these two components and between PMA and the solvent oil.

DEPT is an editing technique for

13C NMR spectra [

39]. By applying polarization transfer to different carbon signals, it enables the selection, nulling, or inversion of specific carbon signals. The results in distinct patterns in the edited spectrum, aiding in the identification of structures corresponding to carbon signal peaks. Specifically, in a

13C DEPT 90 spectrum, only tertiary carbon (CH) exhibits positive absorption signals, while other carbon types (primary carbon CH

3, secondary carbon CH

2, and quaternary carbon C) are nearly zero. In a

13C DEPT 135 spectrum, primary carbon (CH

3) and tertiary carbon (CH) exhibit positive absorption signals, secondary carbon (CH

2) shows negative absorption signals, and quaternary carbon (C) is nearly zero.

Based on this pattern, the structural representation of each signal peak in the 13C NMR spectrum of PMA-2 is identified. Primary carbon (CH3) represents the terminal end of the carbon chain, secondary carbon (CH2) indicates unbranched chain extension, while tertiary carbon (CH) and quaternary carbon (C) denote branching or functionalization of the carbon chain. In the 13C spectrum, only quaternary carbon signals present in the PMA backbone and carbonyl group were observed, with no quaternary carbon signals detected in the side chains. Therefore, it can be concluded that no quaternary carbon exists in the side chains, and the degree of branching in PMA can be measured using the proportion of tertiary carbon. The branching degree of PMA-2 is 0.43%.

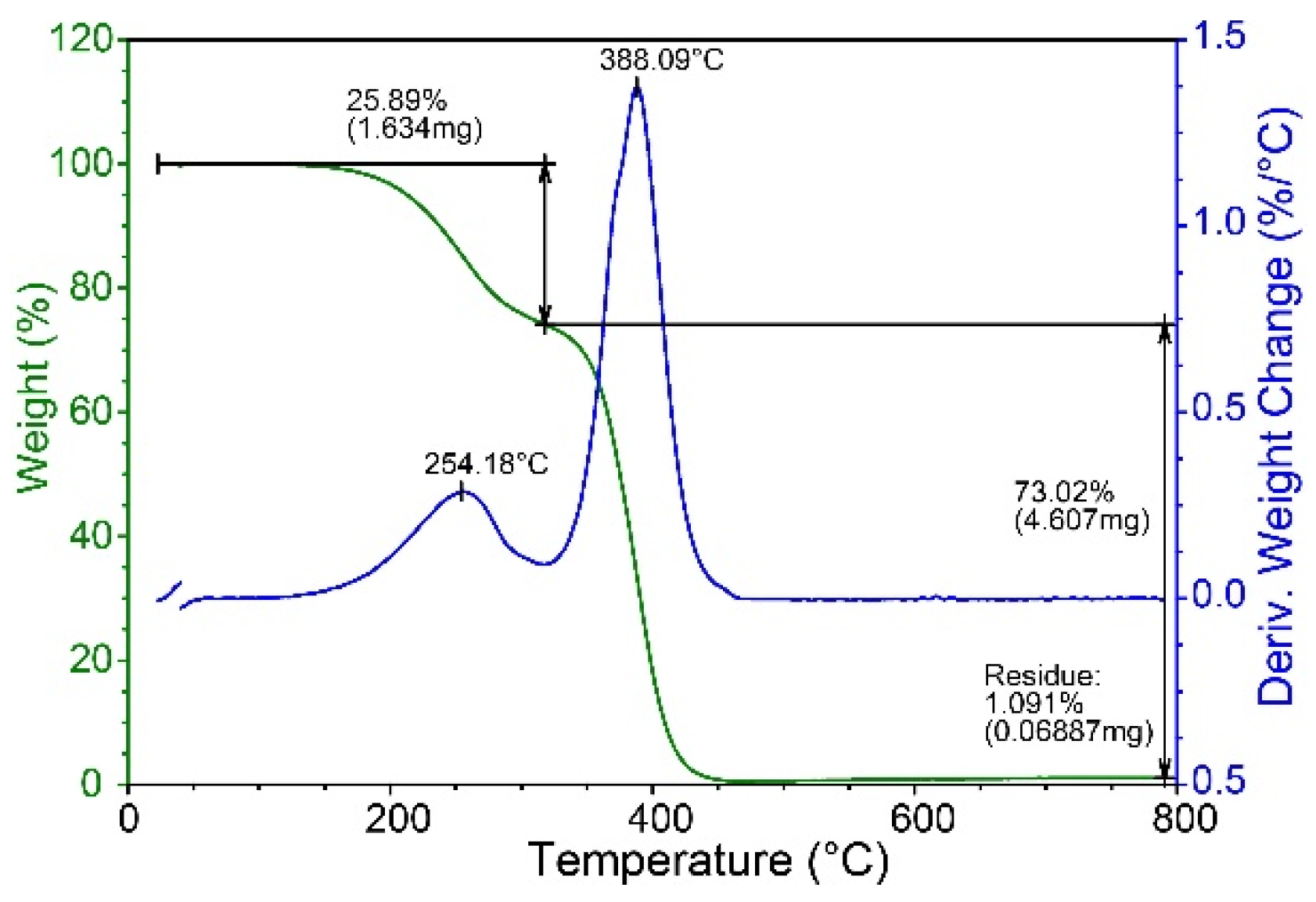

To further confirm the relative proportions of different branches, the branched chains of the PMA must be cleaved and analyzed via pyGC-MS. Thermal decomposition temperatures of PMA, specifically the temperatures at which ester bonds between the poly(methyl methacrylate) backbone and fatty alcohols break, can be measured through TGA-DSC analysis, which provides a reference temperature for setting pyGC-MS conditions. The decomposition products may include methacrylate, the fatty alcohols obtained after the degreasing reaction, and their related products, among which there may also be residual monomers that have not been completely reacted.

As shown in

Figure 3, PMA-2 exhibits near-complete weight loss above 450 °C. Therefore, for pyGC-MS, the temperature should be set at 450 °C or higher to ensure thorough pyrolysis of the PMA sample.

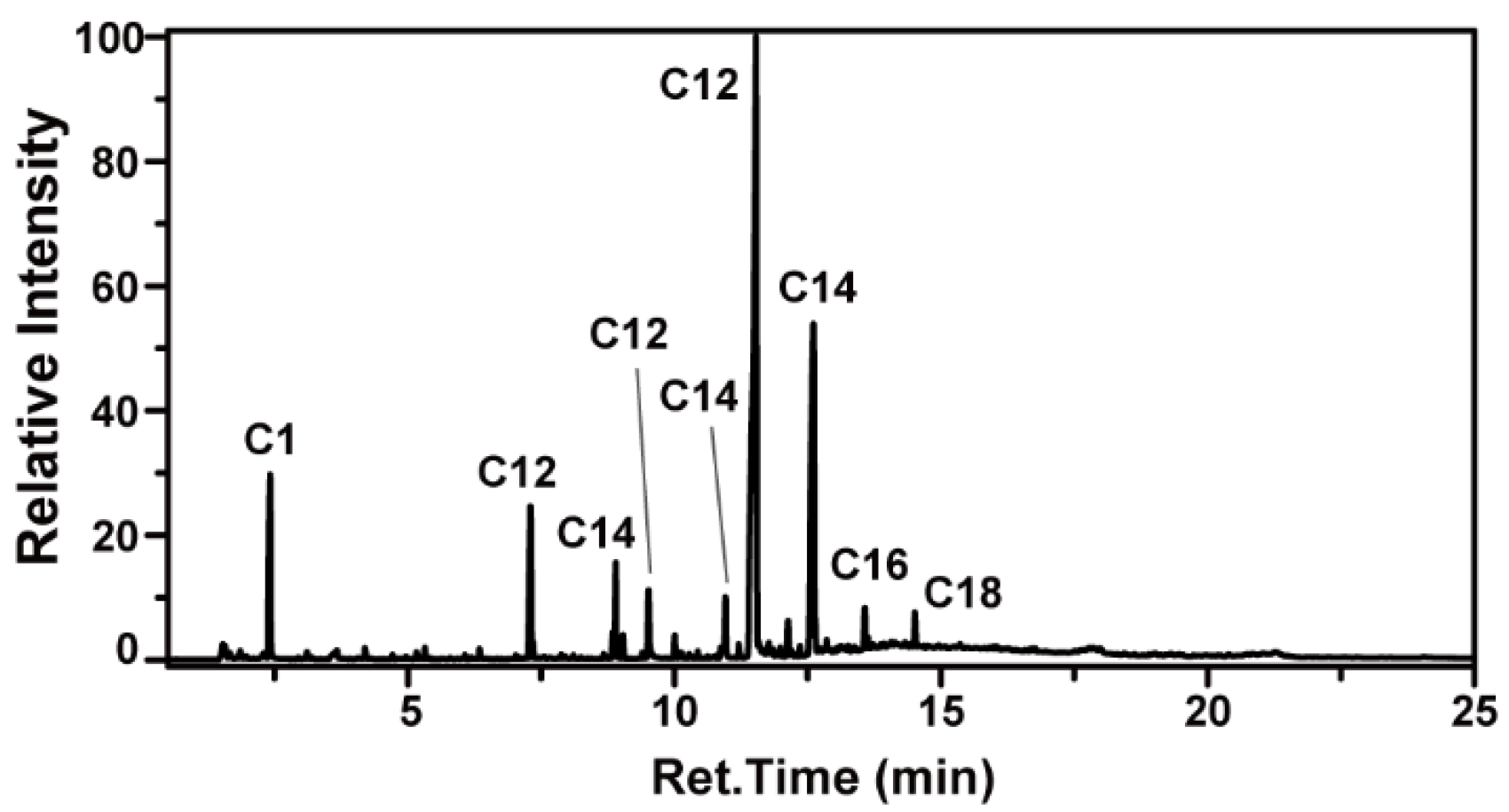

Following this, pyGC-MS was employed to detect fatty alcohol information from the thermally decomposed sample at an appropriate pyrolysis temperature, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

Similar to GC-MS analysis, matching the MS spectra of each component peak yields the structure and proportion of each component. The matching results contained information on methyl acrylate, dodecene, tetradecene, dodecanol, tetradecanol, dodecanol methacrylate, tetradecanol methacrylate, hexadecanol methacrylate, and octadecanol methacrylate. Among these, the alkenes correspond to the dehydration products of fatty alcohols, which may originate from the hydrolysis of ester monomers. The methacrylates represent monomer structures. In PMA-2, fatty alcohols predominantly consist of C12 and C14, accounting for up to 78%, while components with other carbon chain lengths are present in smaller quantities.

Comprehensive analysis of the above data reveals the approximate structure of PMA-2. The analytical methods for the remaining four PMAs are similar. For detailed analysis data of all five PMAs, please refer to the

Supplementary Materials. The structural analysis of the five PMAs involved in this study is summarized in

Table 6.

As shown in

Table 6, the actual content of the five PMAs ranges from 59% to 76%, with solvent oil constituting a significant component of PMA products. Four out of the five PMAs exhibit similar weight-average molecular weights, all falling between approximately 17,000 and 22,000. The sole exception is PMA-5, which has a molecular weight of 6255. The fatty alcohol alkyl chain lengths (excluding methanol) of all five PMAs fall between C12 and C18, with similar and insignificant branching degrees. Three PMAs contain nitrogen, which typically indicates the incorporation of amine-modified functional groups within the PMA structure.

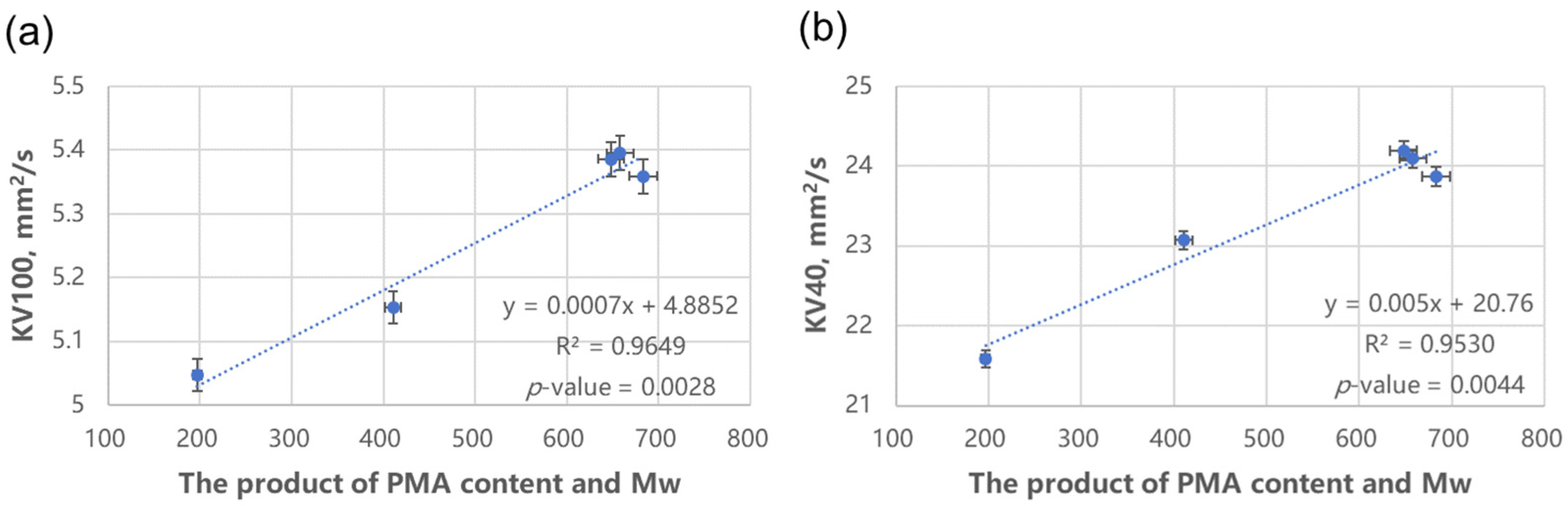

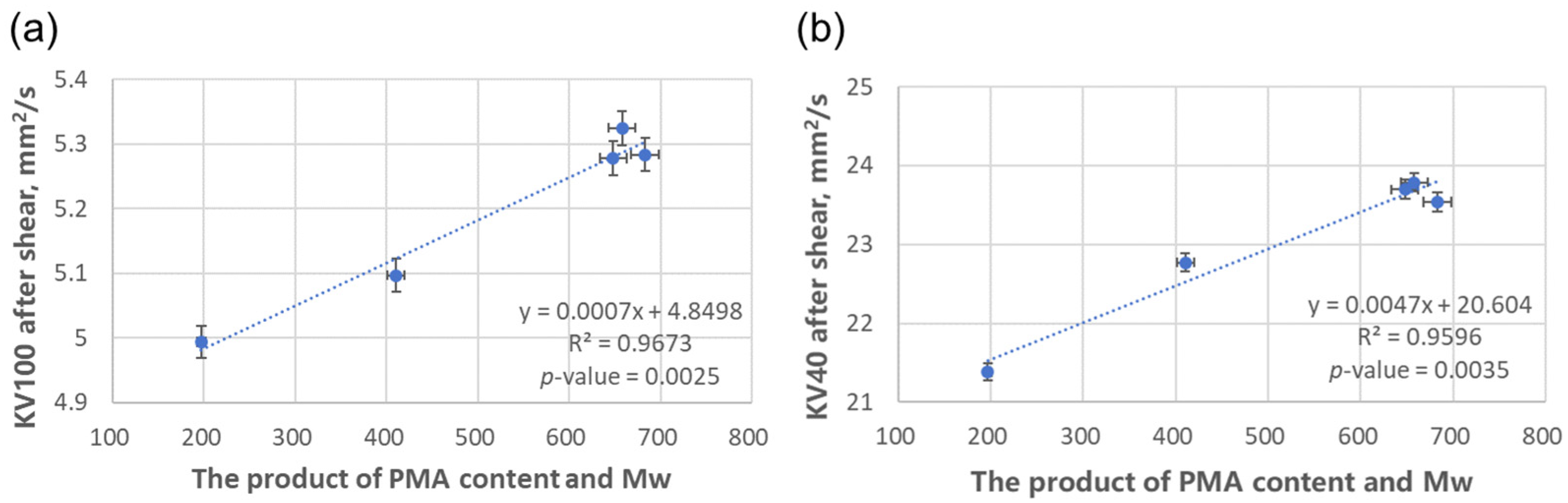

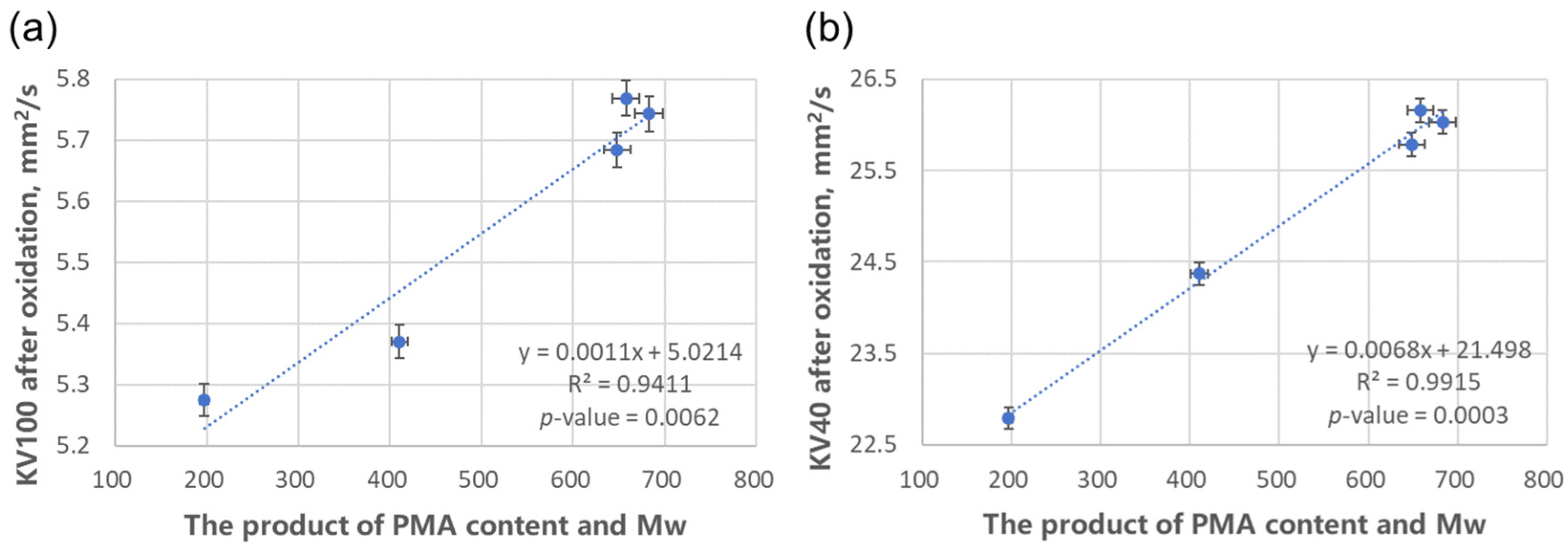

It should be noted that the degree of polymerization and molecular weight are highly correlated (correlation coefficient R2 = 0.906 and the variance inflation factor VIF = 10.64). When conducting data analysis, it is sufficient to select either one of them as the independent variable for the structural influencing factor.

3.3. Relationship Between Lubricant Low-Temperature Performance and PMA Structure

The low-temperature performance data for each formulation of NEV transmission oil are shown in

Table 8.

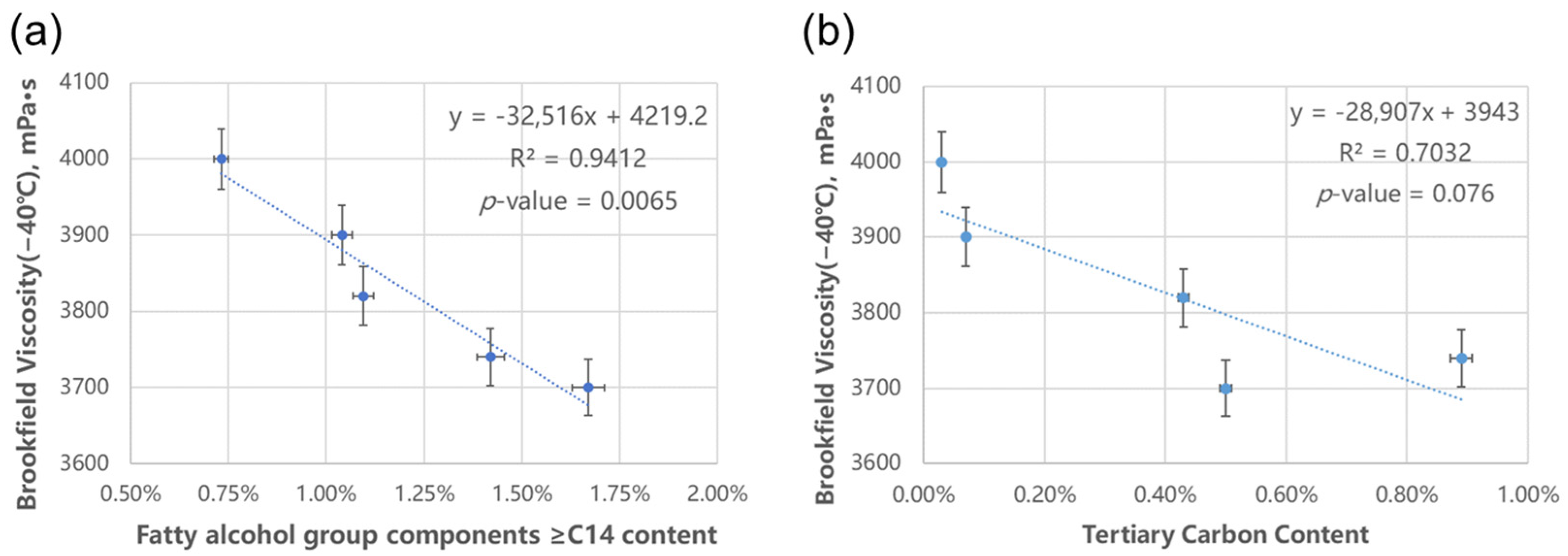

As shown in

Table 8, oils No. 1 and No. 5 exhibit outstanding advantages in pour point and low-temperature apparent viscosity. Research indicates that the chain length and branching degree of fatty alcohols in PMA influence the low-temperature performance of oils. When used as a pour point depressant, the carbon number of the fatty alcohols in PMA should be 12 or higher [

40,

41]. When PMA is used as VII, whether the side chain length also has an impact on the low-temperature performance of the oil has become the focus of attention. By summing up the data of fatty alcohol composition, the content of fatty alcohol group components ≥C12, ≥C14, and ≥C16 can be obtained. Multiply it by the actual content of PMA in the formula, the actual content of the corresponding components in the oil can be calculated. Correlating the actual contents of the corresponding components with the low-temperature performance, we found that the content of the ≥C14 component has the strongest correlation with the Brookfield Viscosity (−40 °C) data, as shown in

Figure 6a. Similarly, the relationship between the tertiary carbon content of PMA and apparent viscosity is illustrated in

Figure 6b.

It can be observed that the low-temperature apparent viscosity (−40 °C) of the formulated oil exhibits a negative correlation with both the content of side-chain components ≥C14 in the PMA and the degree of branching (tertiary carbon content). The correlation coefficient R2 with the content of ≥C14 components reaches 0.94, and the p-value of T-test is far less than 0.05. That is, the higher the content of ≥C14 components, the more effective the PMA viscosity index improver is in optimizing the low-temperature performance of the final oil.

As for the degree of branching, in the current data regression analysis, the p-value exceeds 0.05 but is relatively close to 0.5, which may be a possibility for more in-depth research. Additionally, the collinearity diagnosis for variables was also conducted. The variance inflation factor (VIF) value was 2.20, which is less than 5. Therefore, it can be determined that there is no significant collinearity between the two independent variables. Similarly, MW data also conducted the regression analysis, and the p-value = 0.789, indicating that the relationship between low-temperature performance and molecular weight is relatively weak.