1. Introduction

The performance of lubricating oils is crucial to the service life and operational reliability of aeroengine mainshaft ball bearings. Under high-speed, high-temperature, and heavy-load conditions, the bearing’s frictional and thermal responses directly govern the reliability and efficiency of the entire engine. With the continuous increase in aeroengine performance demands, accurately modeling the frictional behavior of lubricants with varying viscosities under complex operating conditions has emerged as a central challenge in bearing dynamics research.

In the development of lubrication theory, film thickness models have reached a relatively mature stage. The minimum film thickness equation proposed by Dowson et al. [

1], derived from experimental observations and theoretical analysis, has been extensively validated and widely applied in engineering practice. In contrast, the field of friction and traction still lacks a complete quantitative theory that can be directly applied to engineering prediction [

2]. This challenge has persisted in the tribology community since the mid-20th century. Early studies demonstrated that the assumption of a Newtonian fluid and consideration of thermal effects alone could not account for the nonlinear friction coefficients observed experimentally. Smith [

3] and Crook [

4] were the first to recognize this limitation, attributing it to non-Newtonian rheological behavior. Later, Smith [

5] introduced the concept of limiting shear strength, suggesting that once the traction coefficient reaches a critical threshold, the lubricant exhibits solid-like yielding behavior, resulting in an upper bound for the friction coefficient. Building on Smith’s insight, researchers began developing viscosity–shear relationship models by fitting experimental data. Cross, Bingham, Carreau, and Eyring [

6,

7,

8,

9] successively proposed various rheological formulations. Among them, the Eyring and Carreau–Yasuda models gained wide acceptance, as they were able to reproduce the nonlinear features observed in elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) experiments. Johnson et al. [

10,

11] further addressed the complex response of lubricants under high pressure and proposed a constitutive equation coupling the Eyring and Maxwell models to describe isothermal shear behavior. Subsequently, Higashitani et al. [

12] developed a fully coupled finite-element EHL line-contact model that accounts for both shear behavior and thermal effects of lubricants, thereby providing a more rational theoretical basis for improving conventional heat distribution calculations.

However, as research has progressed, although the aforementioned models have provided important insights into lubricant traction behavior, no consensus has yet been reached regarding the selection of an appropriate constitutive traction model [

13,

14,

15]. One group of researchers, represented by Bair et al. [

16,

17], tends to favor Carreau-type shear-thinning models. Their main advantage lies in the ability to describe the transition of lubricants from the Newtonian regime to the power-law regime in a continuous and smooth manner, offering relatively stable numerical implementation. As a result, such models have been widely adopted in recent thermo-elastohydrodynamic lubrication (TEHL) analyses. In contrast, another group of researchers, including Neupert et al. [

18,

19], argues that Eyring-type models exhibit greater physical consistency in describing traction and shear behavior. Under a single set of parameters, the Eyring model is capable of more consistently reproducing both experimentally observed traction levels and molecular-scale shear responses, whereas Carreau-type models tend to overestimate viscosity in low-temperature, high-viscosity regimes. Gao et al. [

20], based on molecular dynamics simulations combined with comparative analyses of multiple rheological models, demonstrated that even for linear alkane systems with relatively simple molecular structures, the choice of shear-thinning model can introduce substantial discrepancies in high-shear predictions. This finding indicates that, even at the level of base lubricants, the selection and calibration of rheological constitutive relations exert a non-negligible influence on numerical results. Furthermore, MacLaren et al. [

21,

22] conducted high-speed EHL experiments with simultaneous measurements of oil-film thickness and traction response, clearly demonstrating that thermal effects play a dominant role in traction behavior under high rotational speeds. Taylor, Cordier, and Liu et al. [

23,

24,

25] separately investigated the influence of contact boundary conditions, surface roughness, and contact geometry on friction coefficients, revealing that even the same lubricant may exhibit markedly different traction characteristics depending on the contact configuration. These findings have led to the recognition that directly equating traction curves with rheological flow curves may involve conceptual oversimplifications [

26]. Overall, as understanding has deepened, research on friction and traction characteristics has gradually shifted from comparisons of individual rheological models toward a more systematic characterization of multi-physical coupling mechanisms [

27]. Recent experimental and numerical studies consistently indicate that lubricant friction and traction behavior is jointly governed by pressure viscosity relationships, temperature rise, shear-rate distributions, and the thermal properties of contact materials. Consequently, due to inherent assumptions and limited applicability, models based solely on lubricant rheology struggle to accurately predict experimental traction coefficients under realistic operating conditions [

28].

To address the requirements of bearing engineering calculations, many researchers have adopted ball–disk test methods to replicate realistic operating conditions and investigate the traction behavior of lubricating films. Wang et al. [

29] and Deng et al. [

30] conducted systematic experiments using ball–disk tribometers under varying loads, speeds, and temperatures. They developed corresponding rheological equations and a five-parameter empirical model, which provided key parameters for bearing dynamic analysis. However, this model employs load as the fitting variable rather than directly reflecting contact stress, thereby limiting its general applicability. In addition, the five-parameter, four-coefficient formulation for the traction coefficient yields a nonzero value at zero slip ratio, introducing inconsistencies in bearing dynamic analysis. Nevertheless, this class of models has been widely applied in studies of bearing frictional power loss, cage dynamics, thermal response, and vibration [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], thereby confirming the profound impact of lubricant properties on the dynamic performance of rolling bearings.

In summary, as the demand for higher accuracy and reliability in the simulation of advanced bearing systems continues to increase, traditional modeling approaches based on rheological constitutive equations remain a matter of considerable debate. On the one hand, there is still no consensus within the research community on whether traction curves can be considered equivalent to rheological flow curves, and the applicability of models such as the Eyring and Carreau formulations remains controversial. Although TEHL methods can comprehensively account for temperature rise and thermo-coupling effects, their engineering application is often restricted by low computational efficiency, poor numerical convergence, and the difficulty of obtaining accurate material parameters [

41]. On the other hand, while existing empirical models still exhibit certain limitations in representing contact stress and predicting the zero slip boundary, they have demonstrated substantial engineering practicality in bearing dynamic simulations and have contributed to advancing the understanding of underlying mechanisms. To address the above issues, this study employs a self-developed ball–disk traction test rig to systematically investigate the oil-film traction characteristics of three aviation lubricants with representative viscosity levels. These include the newly developed 4102 oil (7 cSt) from Sinopec Yiping Chemical Plant, the inservice 4050 oil (5 cSt) from the same manufacturer, and the inservice 4010 oil (3 cSt) from Sinopec Great Wall Lubricant Company. Although the three lubricants differ in kinematic viscosity, they all contain a high proportion of polar polyol ester functional groups within their molecular chains, enabling the formation of stable adsorption films on M50 material surfaces. This contributes to their excellent load-carrying capacity and anti-scuffing performance under high-temperature conditions. Experiments were conducted over a wide range of loads, speeds, and temperatures to comprehensively characterize their traction behavior. Based on the experimentally measured traction force data, a semi-empirical, data-driven traction coefficient model for rolling bearings is proposed. The model possesses clear physical relevance and provides a reliable basis for high-fidelity dynamic simulations of rolling bearings, as well as for lubricant selection in aeroengine applications.

2. Traction Characteristics Tests of Lubricant Oil Films

2.1. Experimental Principle

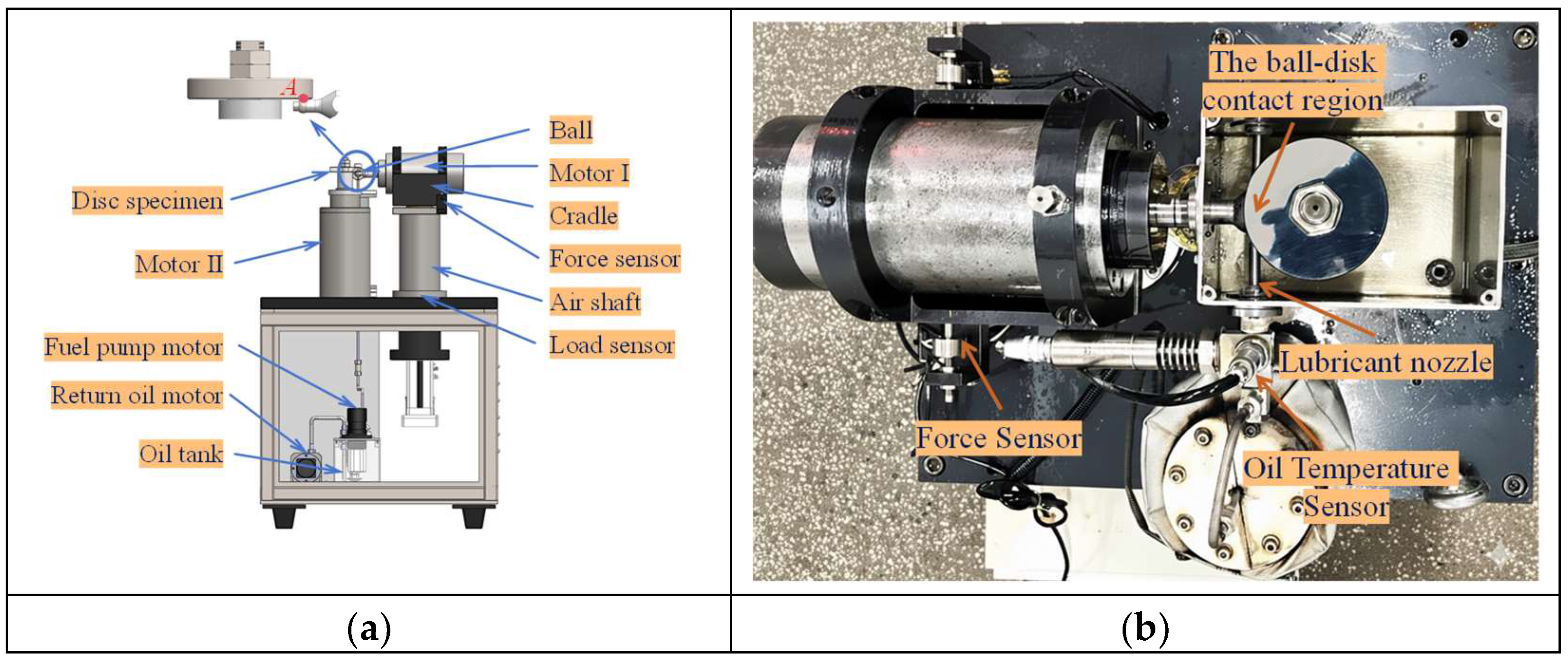

In this study, a self-developed oil-film traction test rig was employed to measure the oil-film traction coefficients of aviation lubricants. The test apparatus adopts a ball–disk configuration (see

Figure 1).

Figure 1a illustrates the overall structure of the system, while

Figure 1b presents the schematic diagram of the test head. In this setup, the ball specimen represents the rolling element of a ball bearing, and the circular disk specimen simulates the bearing raceway. Both the ball and disk specimens are manufactured from M50 material, with a surface hardness of HRC 60–64. The diameters of the ball and disk are 20 mm and 90 mm, respectively. The surface roughness values (

Ra) of the ball and disk are less than or equal to 0.014 μm and 0.01 μm, resulting in a composite surface roughness below 0.017 μm. Since the lubricant film thickness exceeds 0.1 μm, fully developed EHL conditions are ensured. The face runout of the ball–disk pair is controlled below 1 μm, guaranteeing high rotational accuracy. A gas-lubricated air spindle is used to minimize rotational resistance. Owing to its extremely low friction—several orders of magnitude smaller than the traction coefficient of the tested lubricants—the air spindle introduces negligible interference to the measurement accuracy of the traction coefficient. All sensors used in the test rig are high-precision sensors with an accuracy of 0.1%. The load and traction force sensors (Model 102A, BEDELL Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were calibrated using standard weights to ensure the linearity and accuracy of the normal load and traction force measurements. The rolling speed at the ball–disk contact can be continuously adjusted up to 50 m/s. The SRR can be precisely controlled within the range of 0 to 0.3. The maximum Hertzian contact pressure between the ball and disk is adjustable up to 3.0 GPa, and the lubricant inlet temperature can be regulated from ambient conditions to 150 °C. The normal load is applied using a servo electric actuator, the temperature is controlled through a PID regulator, and the rotational speeds are monitored and adjusted via Hall-effect sensors. These components represent high-precision instrumentation commonly used in advanced tribological testing, thereby ensuring high measurement accuracy of the traction tests.

The ball specimen is affixed to a horizontally oriented electric spindle (Spindle I). Spindle I is secured to a cradle, which permits free rotation in the horizontal plane about an air-lubricated vertical axis. Precise positioning of the ball specimen at the designated contact point A on the disk is achieved by adjusting the horizontal location of Spindle I on the cradle. Conversely, the disk specimen is installed on a vertically oriented electric spindle (Spindle II), which is rigidly mounted on the machine frame. The axes of the two spindles are configured orthogonally. The vertical position of Spindle I can be precisely adjusted via the air spindle, thereby enabling the upward movement of the ball specimen to establish contact with the disk and apply the load. The applied load W is measured by a force sensor located at the base of the air spindle. Upon application of the load, elastic deformation is induced at the ball–disk interface, causing the initial point contact to expand into a circular contact zone of very small radius. The maximum Hertzian contact stress between the ball and disk is determined using Hertzian elastic contact theory. During high-speed operation under fully flooded lubrication-where lubricant is continuously directed through an oil nozzle onto the contact region-an EHL film of finite thickness develops between the ball and the disk. The presence of relative sliding between the two contacting surfaces induces shear within the lubricant film, which in turn generates traction forces at the interface.

Under the action of the EHL traction force, the ball specimen, motorized spindle I, and its supporting cradle undergo a slight angular deflection about the axis of the aerostatic vertical spindle. This deflection presses against the traction force sensor mounted on the machine frame, enabling the measurement of the pure oil-film traction force F, free from rolling-resistance components. When a rolling–sliding velocity difference exists between the ball and the disk, elastic compliance between the air spindle and the cradle generates a tangential traction force. This tangential force further induces a small rotation of the ball specimen, motorized spindle I, and the cradle around the vertical air-spindle axis, allowing the traction force sensor to accurately capture the magnitude of the EHL oil-film traction force.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

The test begins by setting the entrainment speed

U. After loading, the ball and disk specimens come into point contact at position

A. Assuming pure rolling at

A, the linear speeds of the ball and disk at this point are equal, i.e.,

U1 =

U2. The entrainment speed is defined as:

Thus, the rotational speeds of Spindle I and Spindle II are determined as:

where

R1 and

R2 are the radii from each spindle axis to the contact point on the ball and disk, respectively.

Under fully flooded lubrication, the surfaces near the contact region form a continuous lubricant film. When Spindle I and Spindle II rotate at n1 and n2, respectively, the ball and the disk achieve pure rolling at point A, with no relative sliding. In this state, the lubrication film at the interface produces only a normal hydrodynamic supporting force and no traction force. Consequently, the ball, together with Spindle I, does not experience lateral deflection, and the traction force sensor outputs zero. To eliminate the influence of residual friction in the system on the subsequent traction measurements, the zero output under pure rolling conditions is set as the reference baseline for the traction force acquisition system.

With the load

W, entrainment speed

U and temperature

T held constant, a specified SRR is produced by decreasing the rotational speed of the ball specimen while simultaneously increasing the rotational speed of the disk specimen. This adjustment yields a targeted sliding velocity Δ

U at the contact. The rotational speeds of the ball and disk are then given by:

The resulting SRR is defined as

S = Δ

U/

U. The elastohydrodynamic traction force drives the ball, Spindle I, and the cradle to deflect as a unit about the vertical axis. This lateral deflection compresses the traction force sensor mounted on the frame, and the acquisition system records the traction force

F generated by the lubricant film. The traction coefficient is then calculated as:

By repeating the procedure at successive values of ΔU, the μ–S curve is obtained to characterize the lubricant’s traction behavior.

2.3. Test Lubricants

The characteristic parameters of the three representative lubricants, including density, kinematic viscosity, thermal conductivity, and specific heat capacity, are evaluated at 100 °C and summarized in

Table 1.

2.4. Experimental Results

The traction tests of the lubricant film were conducted entirely within the EHL regime. The test conditions were determined based on theoretical calculations to ensure a film thickness ratio of

λ > 3 in the ball–disk contact zone, thereby guaranteeing full-film lubrication. The corresponding test parameters for the lubricant traction measurements are listed in

Table 2.

Traction tests were carried out under the combinations of inlet temperature, entrainment speed, and maximum Hertzian stress listed in

Table 2. For each lubricant, 72 sets of traction-coefficient–SRR curves were obtained based on the operating conditions specified in

Table 2, providing a sufficiently comprehensive experimental database for the subsequent development of the lubricant traction model.

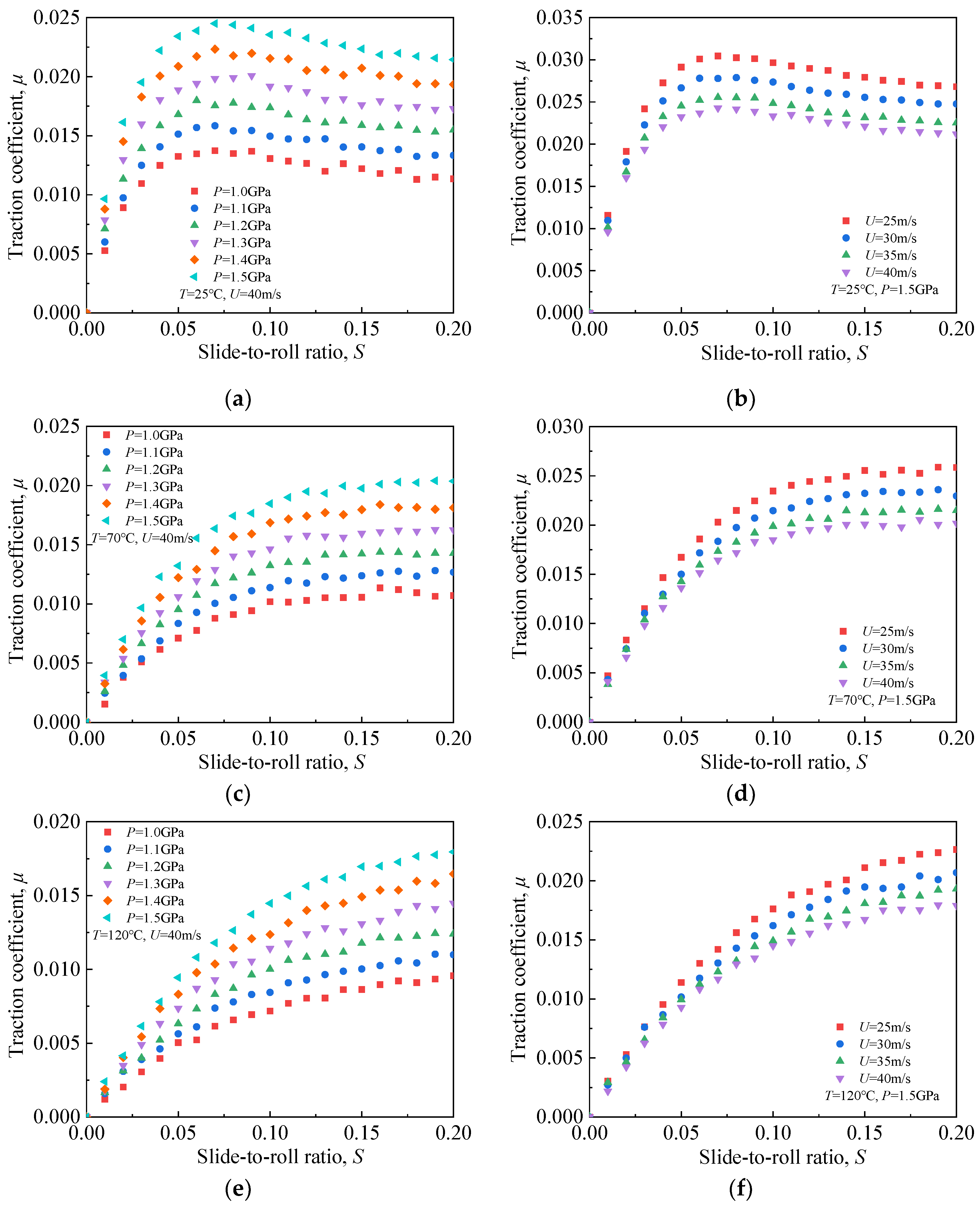

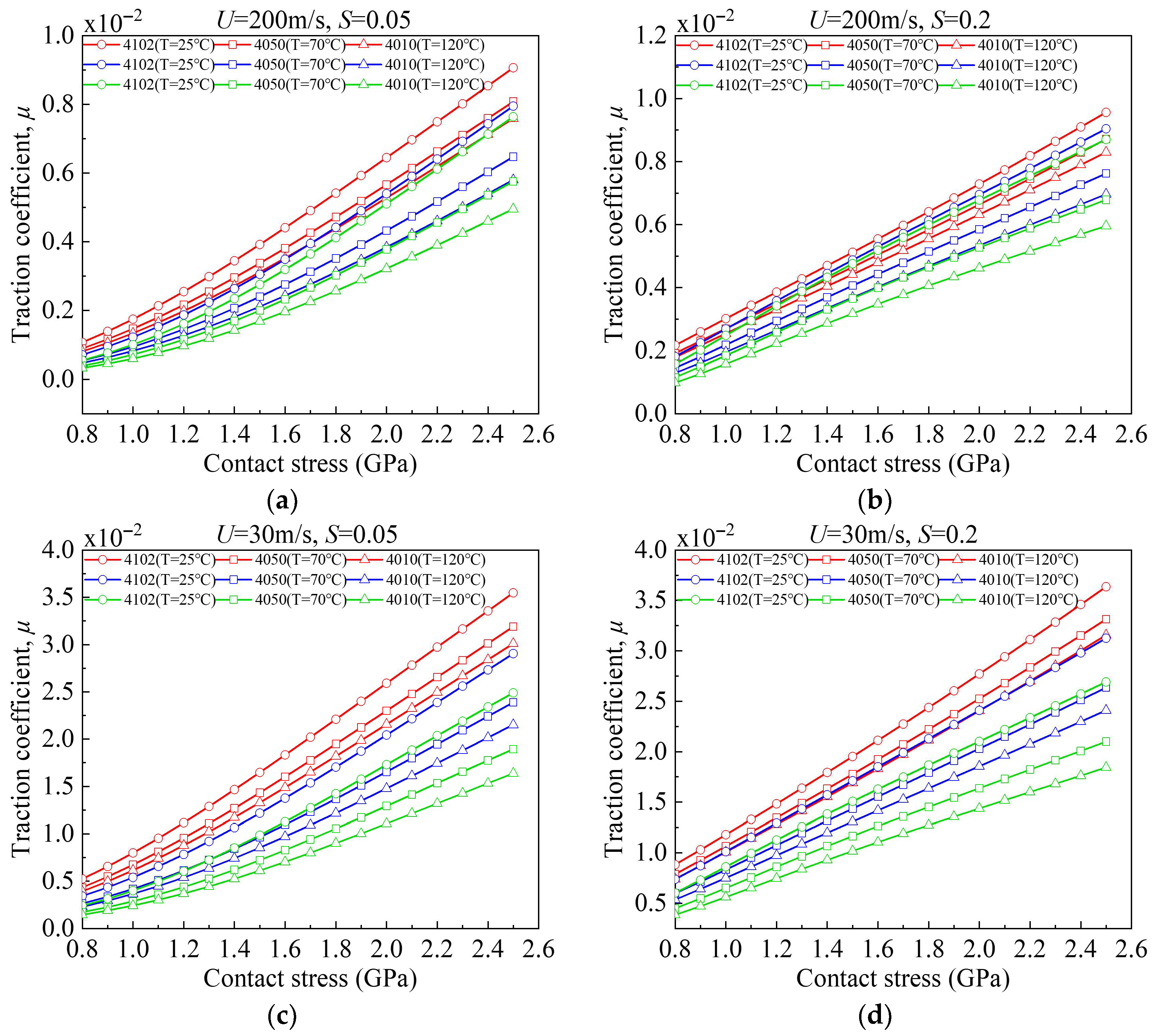

Taking lubricant 4102 as an example,

Figure 2 presents representative traction-coefficient curves under several typical operating conditions. As shown in

Figure 2, when the inlet temperature, entrainment speed, and maximum contact stress are held constant, the traction coefficient initially increases almost linearly with increasing SRR. In this region, the lubricant exhibits typical Newtonian behavior, where shear stress is proportional to shear rate. When the SRR exceeds a certain threshold, the rate of increase in traction coefficient gradually slows, and a pronounced nonlinear relationship emerges between the traction coefficient and SRR, indicating clear non-Newtonian behavior. As the SRR continues to increase, the traction coefficient eventually reaches a maximum value. Beyond this point, further increases in SRR cause a slight decline in the traction coefficient. The experimental traction curves in

Figure 2 demonstrate that the lubricant undergoes a transition from viscoelastic to plastic behavior. The shear stress increases with shear strain rate, and under conditions of high pressure and high shear rate, the lubricant approaches its limiting shear stress.

In addition, the oil-film traction coefficient exhibits an overall decreasing trend with increasing oil supply temperature. This behavior is primarily attributed to the temperature-induced reduction in the lubricant’s base viscosity, pressure–viscosity coefficient, and limiting shear stress. At high entrainment speeds, this effect is further amplified by shear heating, which weakens the effective shear load-carrying capacity of the lubricant film. As a result, the overall traction level shifts downward and enters the saturation regime at lower SRR values.

3. Development of the Traction Model

Based on the data from the oil-film traction tests, a mathematical model was con-structed. The primary challenge lies in capturing the potential functional structure among the variables. By integrating the measured curve trends of three types of aviation lubricants under various working conditions and combining with professional experience, the mapping relationship between the oil-film traction coefficient

μ and the SRR

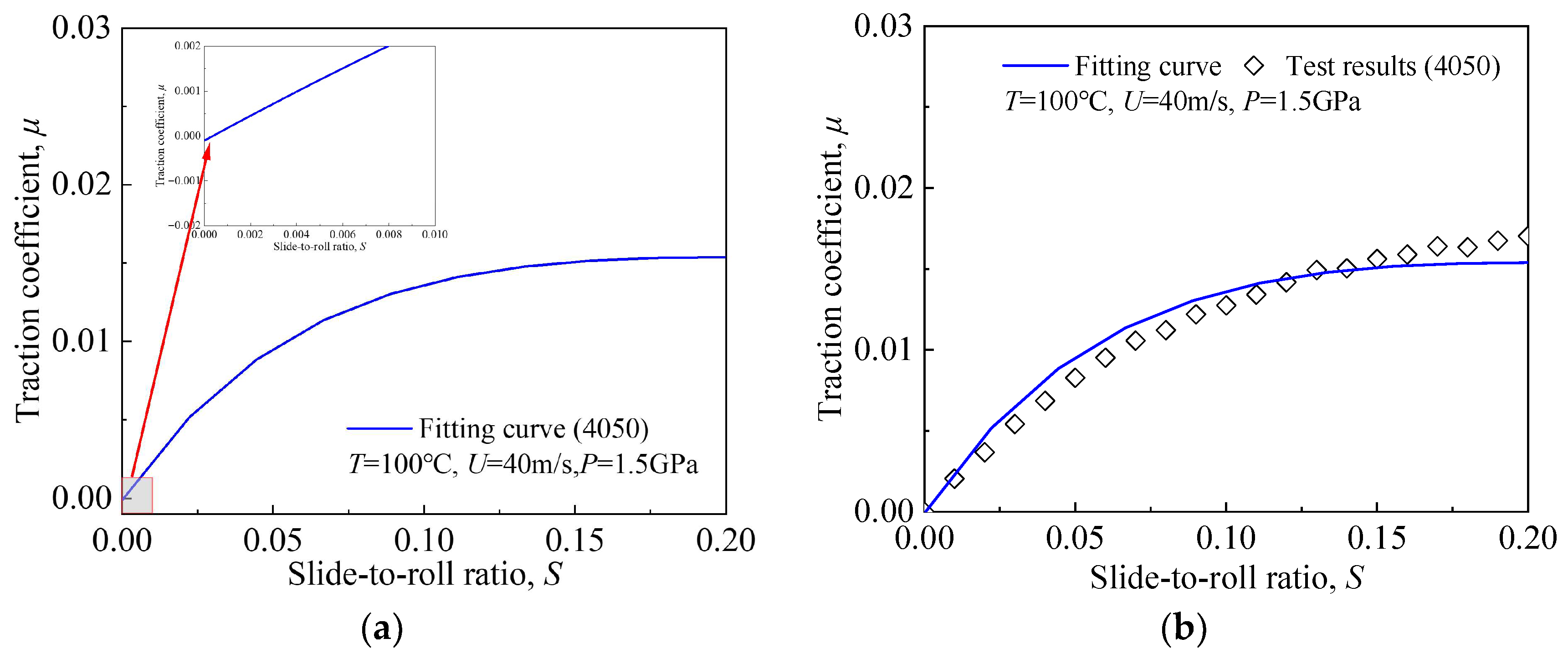

S can be described using the exponential saturation function in Equation (7). Equation (7) satisfies the physical boundary condition

μ = 0 at zero SRR. With increasing SRR, the exponential term decays monotonically, and the traction coefficient asymptotically approaches a finite saturation level governed by the fitted parameter

A, which is consistent with the experimentally observed traction behavior under EHL conditions.

where

S represents the SRR, while

A,

B, and

C are the condition-sensitive coefficients, whose values depend on the maximum contact stress, the supply oil temperature, and the entrainment speed. These values can be uniquely determined through the least squares fitting of the experimental data. During the regression process, sign constraints are imposed on the model parameters, with parameter

A required to be negative and parameters

B and

C positive. These constraints ensure that the predicted traction coefficient remains non-negative under all operating conditions and effectively eliminate non-physical negative values. Based on this formulation, a traction calculation model characterized by four governing parameters and three fitted coefficients is established.

To establish a general traction coefficient model applicable over a wide range of load, speed, and temperature conditions, a nonlinear multivariate regression framework based on dimensionless variables is adopted. Reference values are selected as

P0 = 1 (GPa),

U0 = 20 (m/s), and

T0 = 20 (°C). Accordingly, the maximum contact stress

P, entrainment speed

U, and inlet temperature

T are nondimensionalized as:

Since the coefficients

A,

B, and

C are dependent on the maximum contact stress, entrainment speed, and inlet temperature, they can be expressed as functions of these parameters.

where

A0~

A3,

B0~

B3, and

C0~

C3 are constants that can be determined from the results of the oil-film traction characteristic tests.

By substituting Equation (9) into Equation (7), once the contact stress, entrainment speed, and lubricant inlet temperature are specified in the traction test, the traction coefficient of the lubricant becomes a function of the twelve constants

A0~

A3,

B0~

B3, and

C0~

C3. Accordingly, the theoretical traction coefficient can be expressed as

μ =

f (

A0,

A1,

A2,

A3,

B0,

B1,

B2,

B3 C0,

C1,

C2,

C3) For each lubricant, 72 traction tests were conducted, yielding 72 traction coefficient–SRR curves. To determine the twelve constants, the optimization objective was defined as the sum of squared error between the theoretical traction coefficient

μ and the experimental values

μtest across all operating conditions and SRR data. Letting Ω denote the dataset consisting of all test conditions and SRR values, the objective function is expressed as:

where

A0~

A3,

B0~

B3, and

C0~

C3 are treated as optimization variables, and the constraint condition is that the traction coefficient

µ must be greater than or equal to zero.

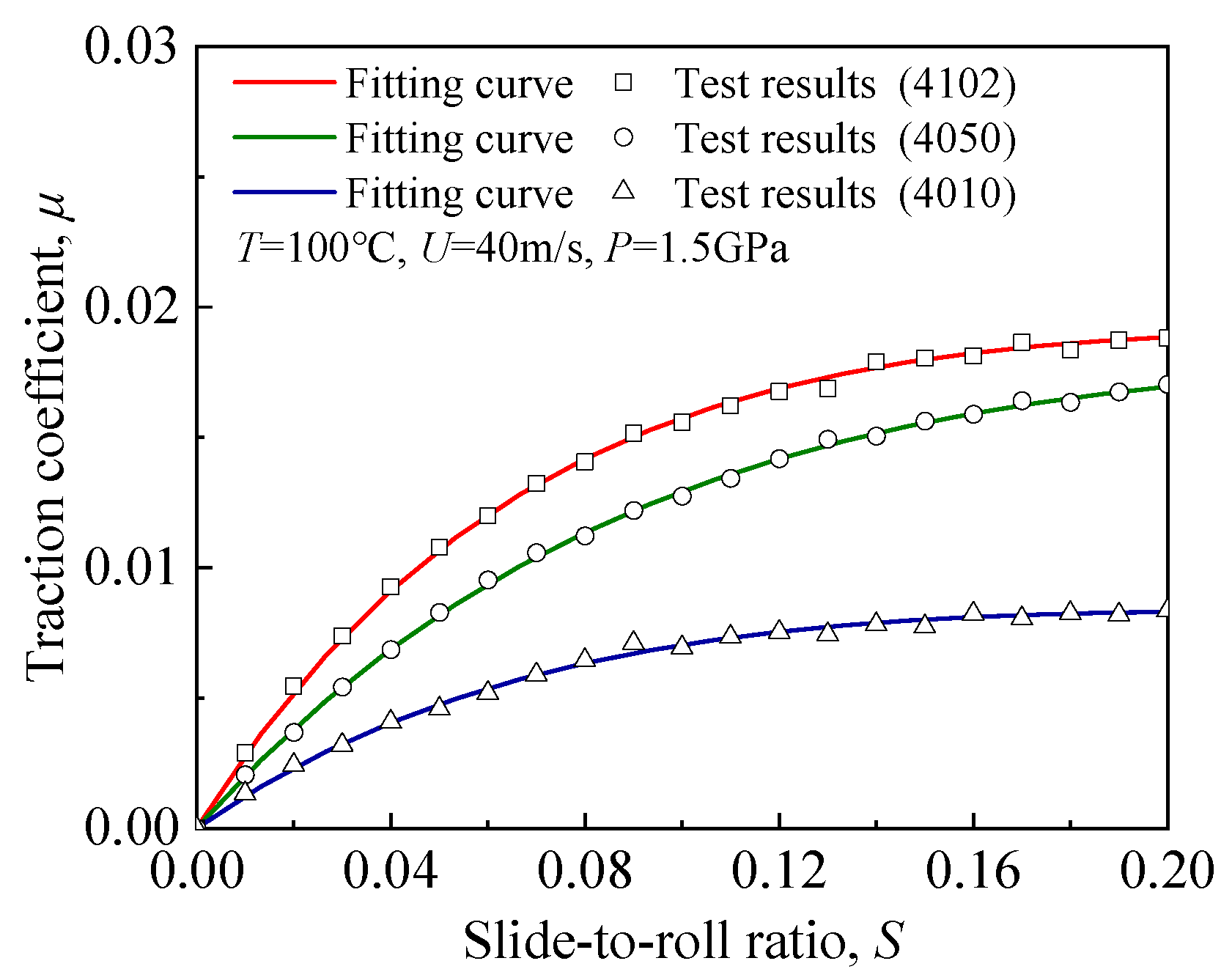

A genetic algorithm was employed to optimize the objective function, and the optimal solutions for the twelve constant parameters were obtained. Based on these results, the specific forms of Equation (9) corresponding to each lubricant can be determined.

Based on the traction test results of lubricants 4102, 4050, and 4010, data regression yielded the following expressions for the coefficients A, B, and C in the traction coefficient model:

For lubricant 4102 (7 cSt):

For lubricant 4050 (5 cSt):

For lubricant 4010 (3 cSt):

By substituting Equations (11)–(13) into Equation (7), the theoretical traction-coefficient formulations for each lubricant are obtained. These formulations can be directly applied in rolling bearing dynamic analyses.

5. Conclusions

In this study, comprehensive traction data were obtained on a ball–disk test rig for three aviation lubricants, including the newly developed 4102 (7 cSt) and the inservice grades 4050 (5 cSt) and 4010 (3 cSt), across the full range of operating conditions. The experimental results clarified the dominant influence of viscosity on oil-film traction behavior. Based on these findings, a four-parameter and three-coefficient engineering model was developed by using the maximum Hertzian contact stress as the independent variable. This formulation eliminates the non-physical paradox of nonzero traction at zero slip and the overfitting problem reported for the five-parameter and four-coefficient model proposed by Wang and Deng. It also avoids the abnormal traction behavior observed in traditional load-based models, which arises from geometric scaling effects of the ball specimen. The traction model proposed in this work exhibits excellent extrapolation capability and prediction accuracy. It can be directly integrated into aeroengine mainshaft bearing dynamic simulation frameworks, enabling rapid lubricant selection and reliable bearing performance evaluation. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Lubricant viscosity exerts a significant influence on the oil-film traction coefficient. Higher viscosity consistently leads to higher traction. Under identical operating conditions, lubricant 4102 exhibits the highest traction coefficient, followed by 4050, whereas 4010 shows the lowest traction response.

(2) The oil-film traction coefficient increases significantly with increasing load. In contrast, higher temperature and higher entrainment speed both lead to a reduction in traction, and the weakening effect induced by entrainment speed is particularly pronounced.

(3) The SRR governs the transition of lubricant flow behavior. At low SRR, the oil-film traction coefficient increases linearly with SRR, indicating Newtonian fluid behavior. After the SRR exceeds a critical value, the rate of increase in traction slows, and the lubricant exhibits non-Newtonian shear-thinning behavior. With further increases in SRR, the traction coefficient approaches a stable plateau, and the three lubricants display a similar limiting trend.

(4) The guideline for selecting lubricants for aeroengine ball bearings is as follows. Under high-speed, light-load and high-temperature conditions in which the cage slip ratio exceeds 15 percent, the high-viscosity lubricant 4102 should be prioritized to compensate for insufficient traction and to suppress sliding. When the cage slip ratio does not exceed 15 percent and adequate lubrication is ensured, the low-viscosity lubricant 4010 is preferred in order to reduce frictional heating, with 4050 as the secondary option.