Enhancement of Wear Behaviour and Optimization and Prediction of Friction Coefficient of Nitrided D2 Steel at Different Times

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Material

2.2. Treatment Details

3. Results

3.1. Microstructural Characterization

3.2. Chemical Composition

3.3. Microhardness

3.4. Wear Behavior

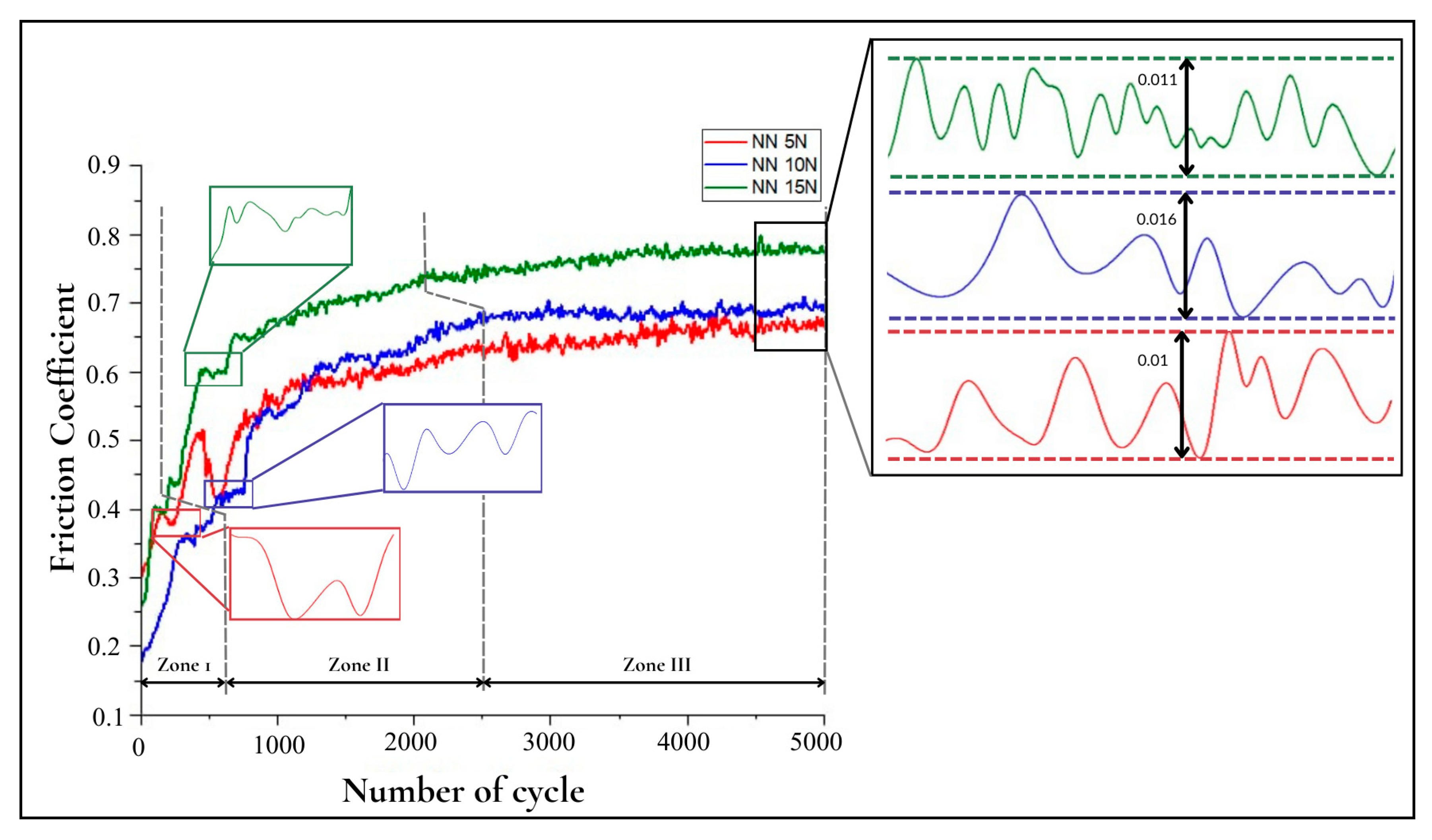

3.4.1. Influence of Normal Force (F)

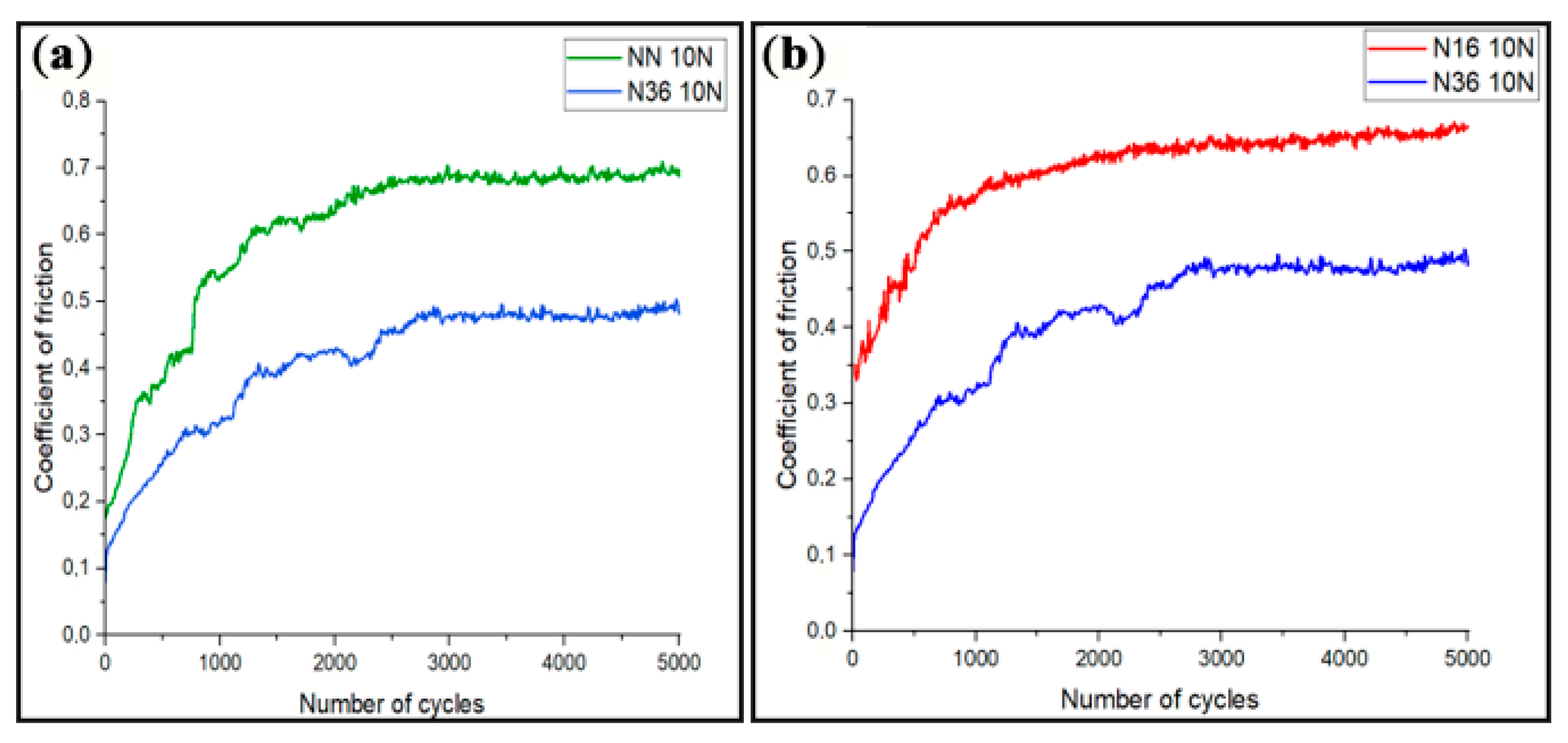

3.4.2. Influence of Nitriding Treatment

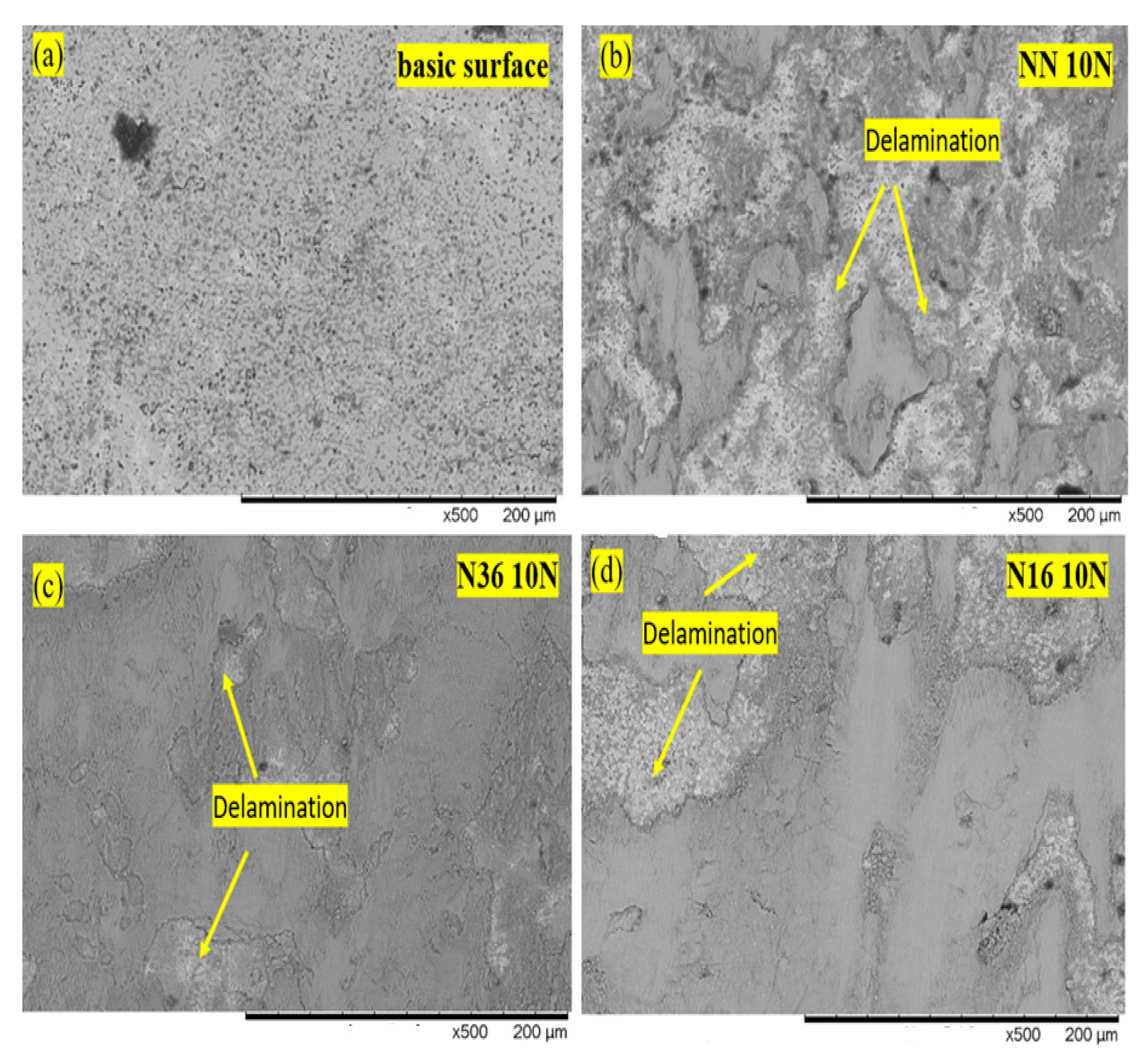

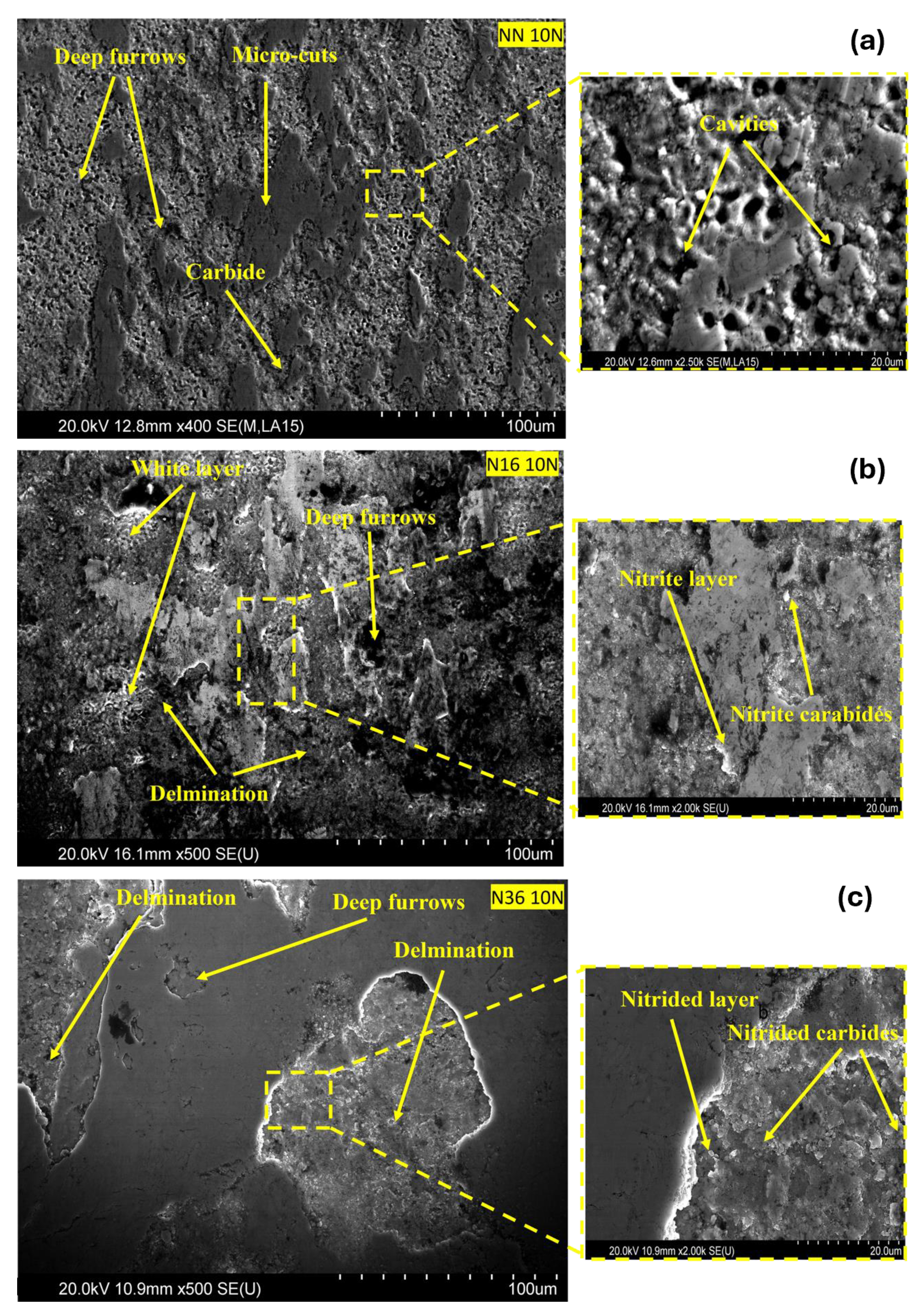

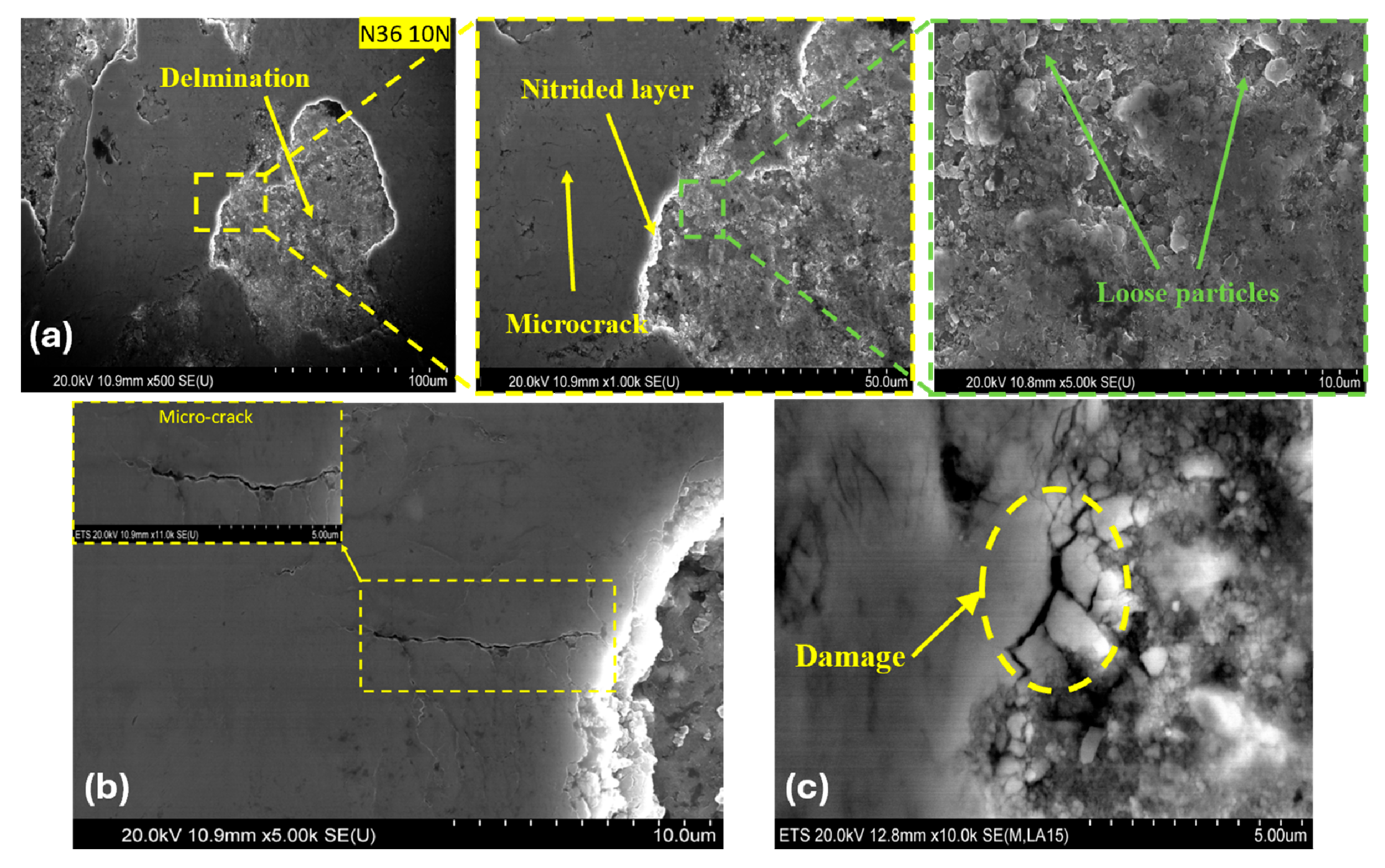

3.4.3. Wear Microstructure

3.4.4. Degradation Mode

3.5. Optimization

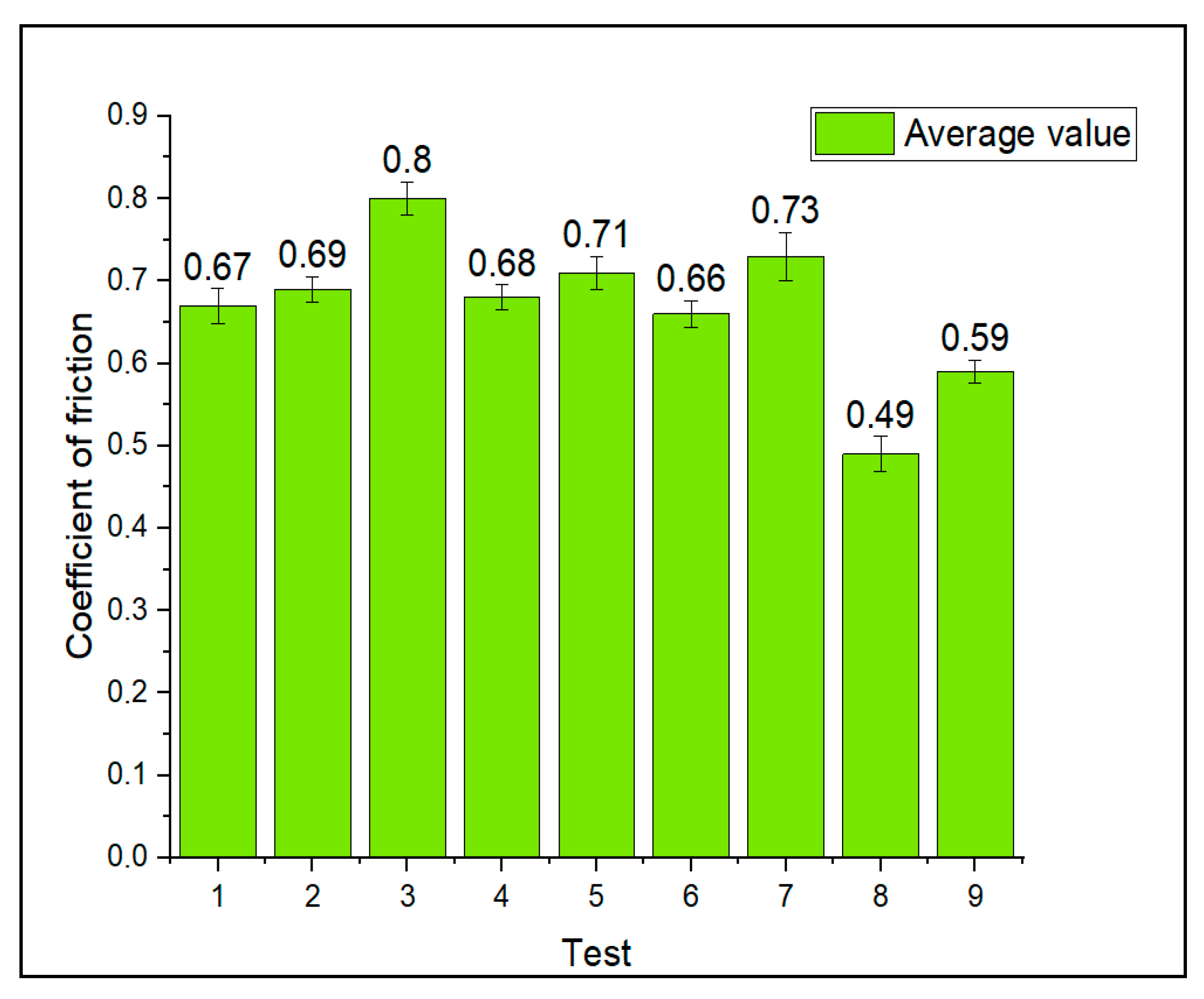

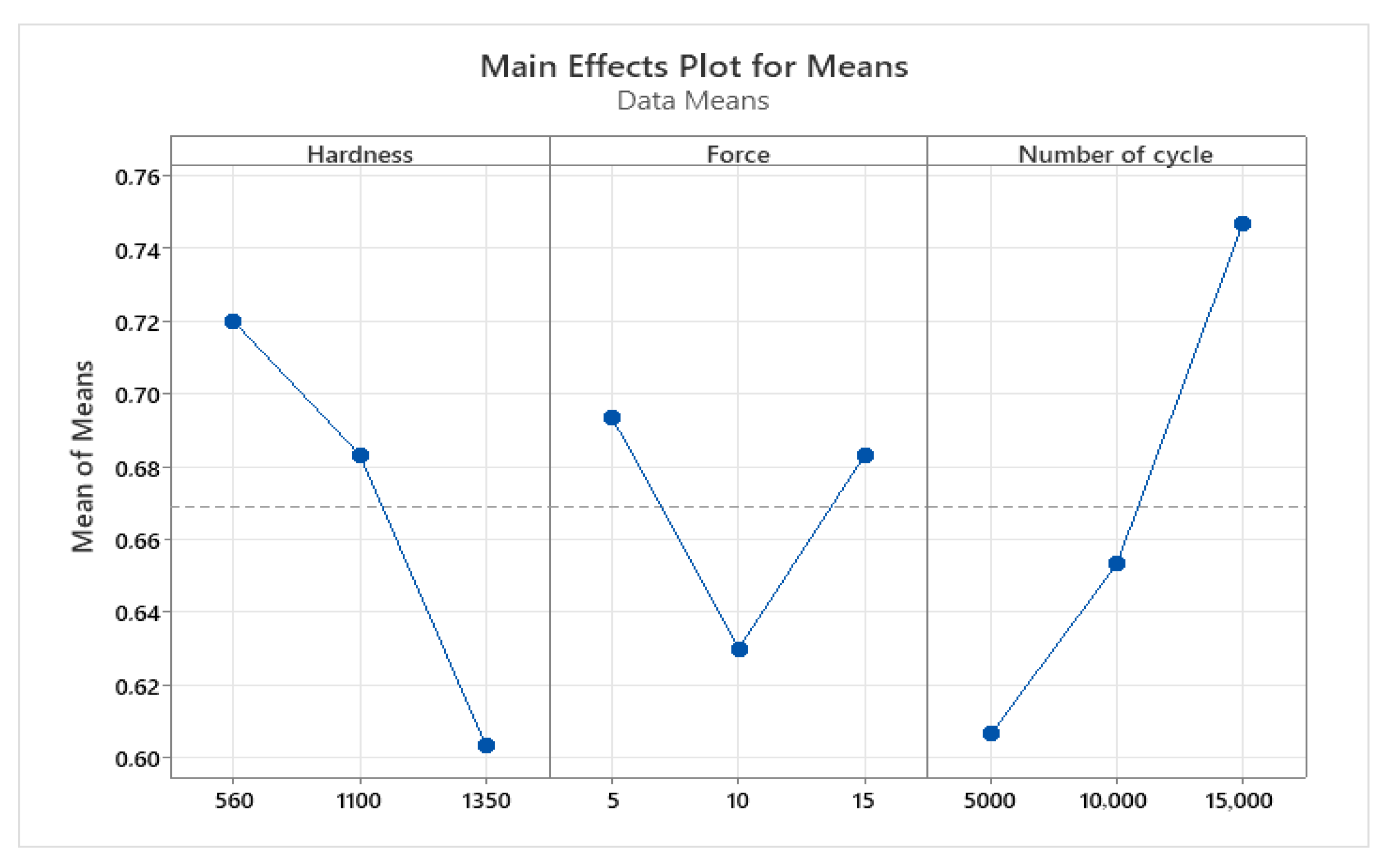

3.5.1. Main Effects of the Parameters

3.5.2. Regression Equation

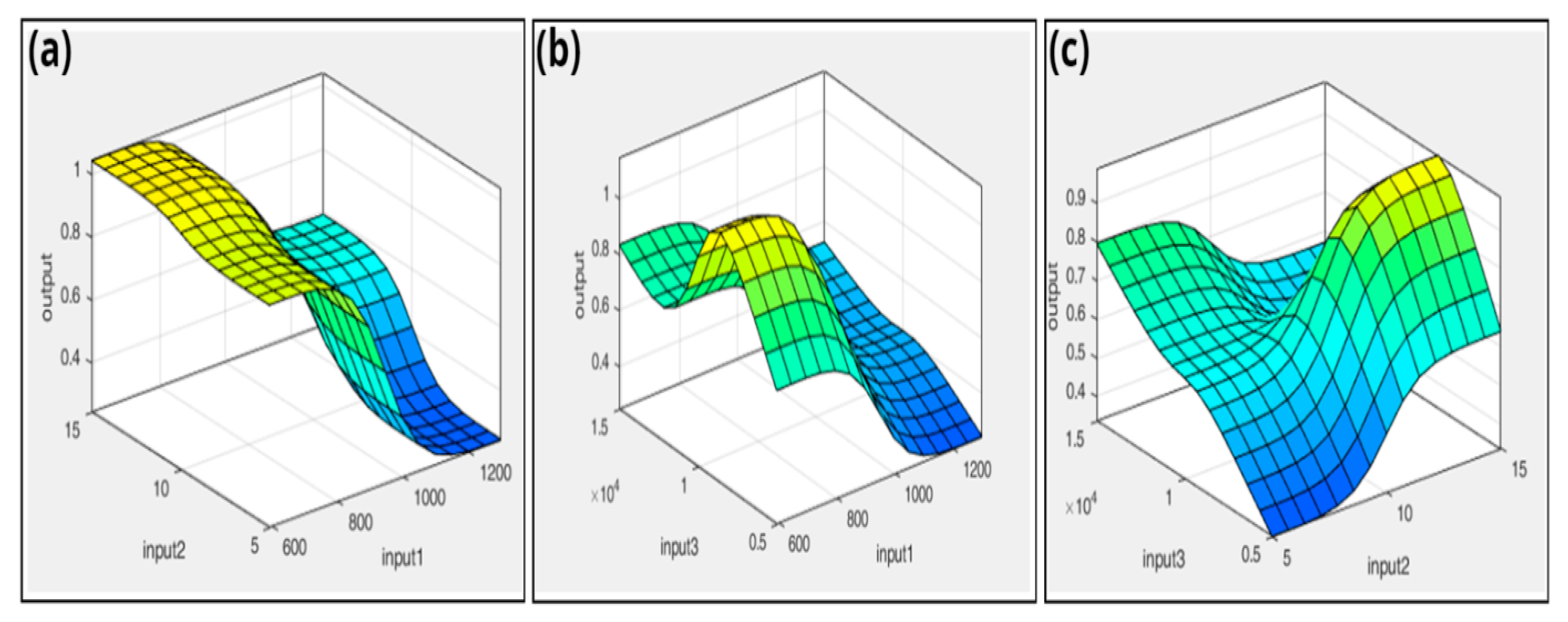

3.5.3. Interactive Influence of Wear Conditions on the COF

3.5.4. Analysis of Variance

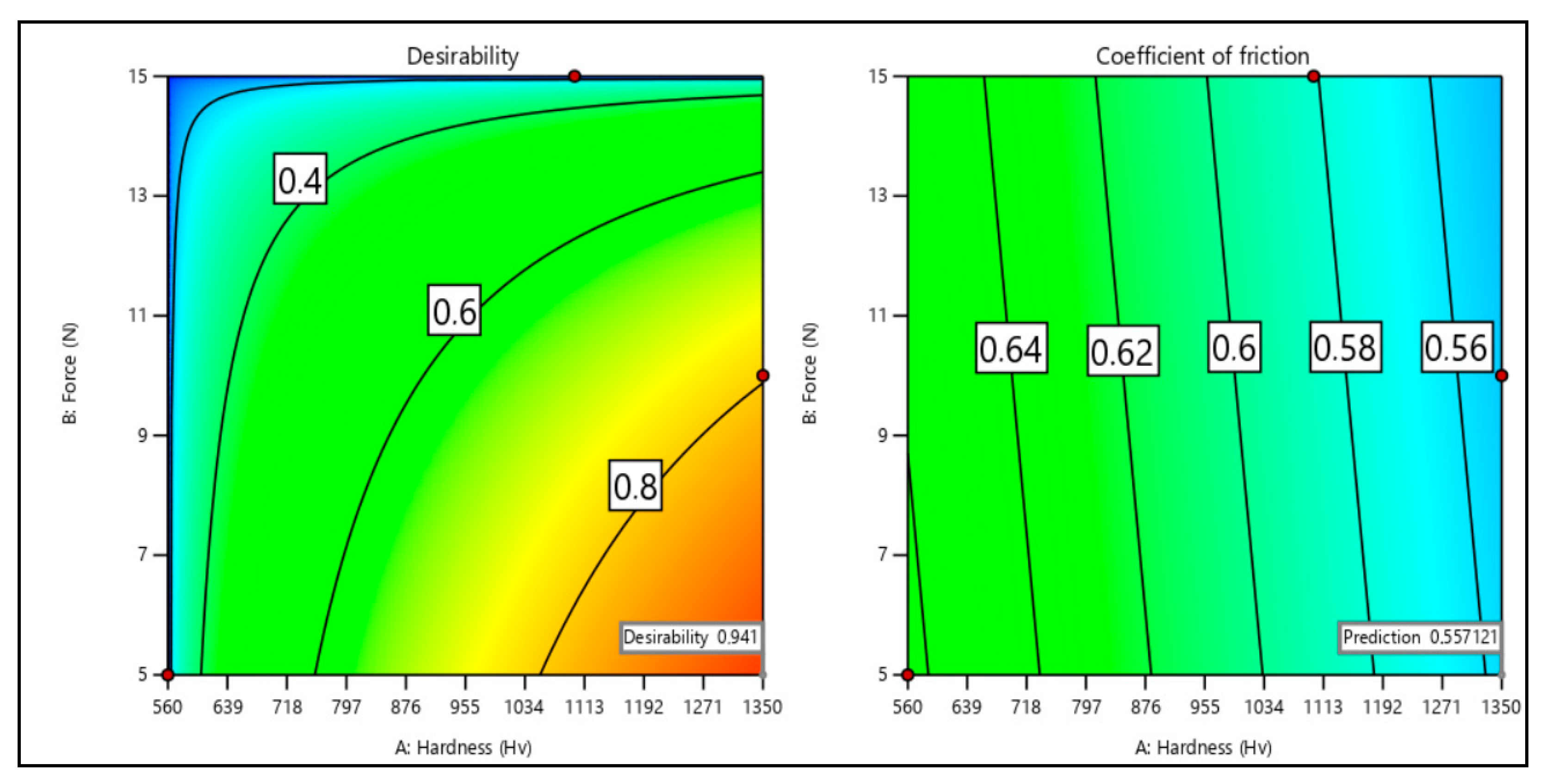

3.5.5. Desirability

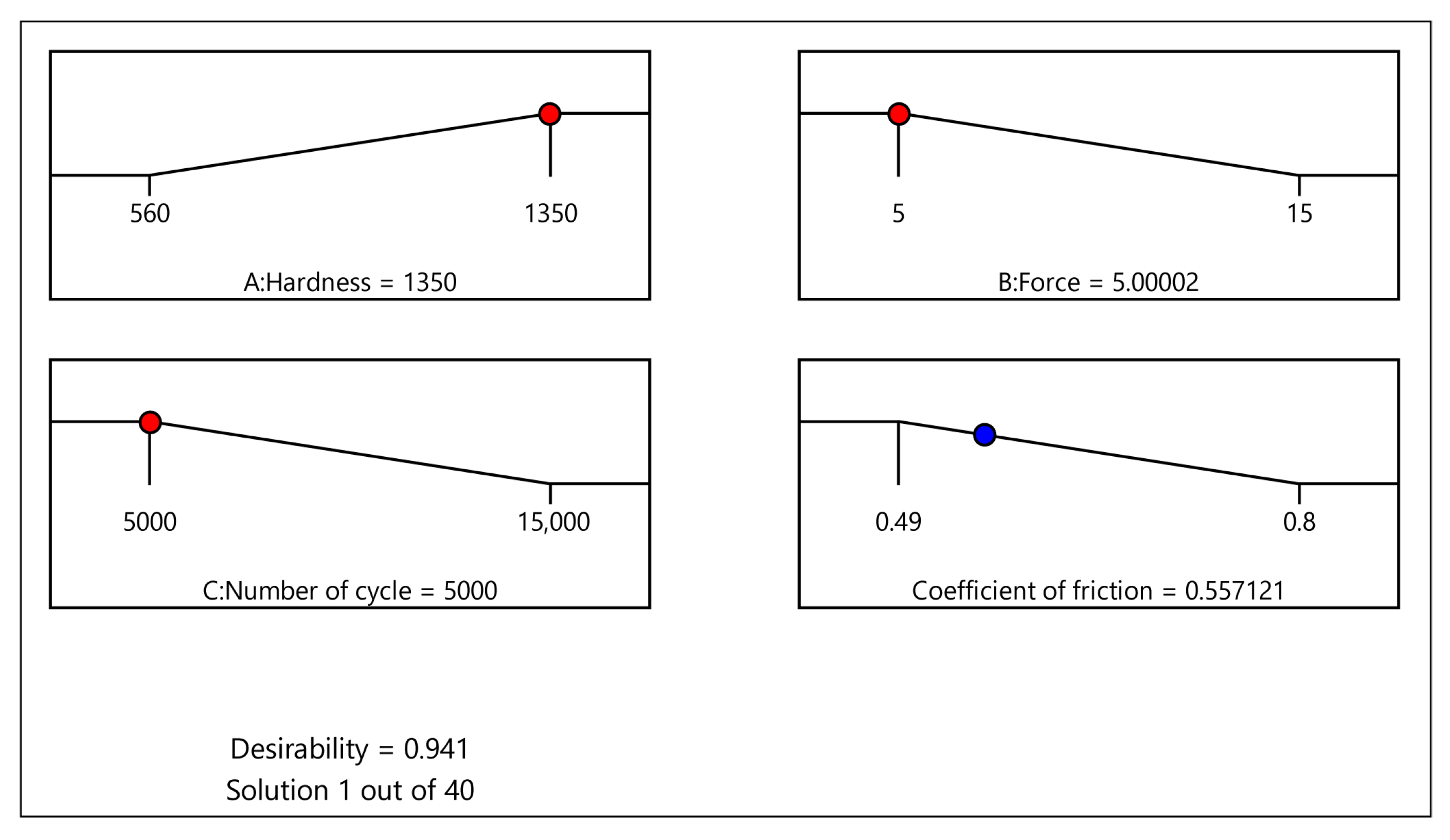

3.5.6. Optimum Solution

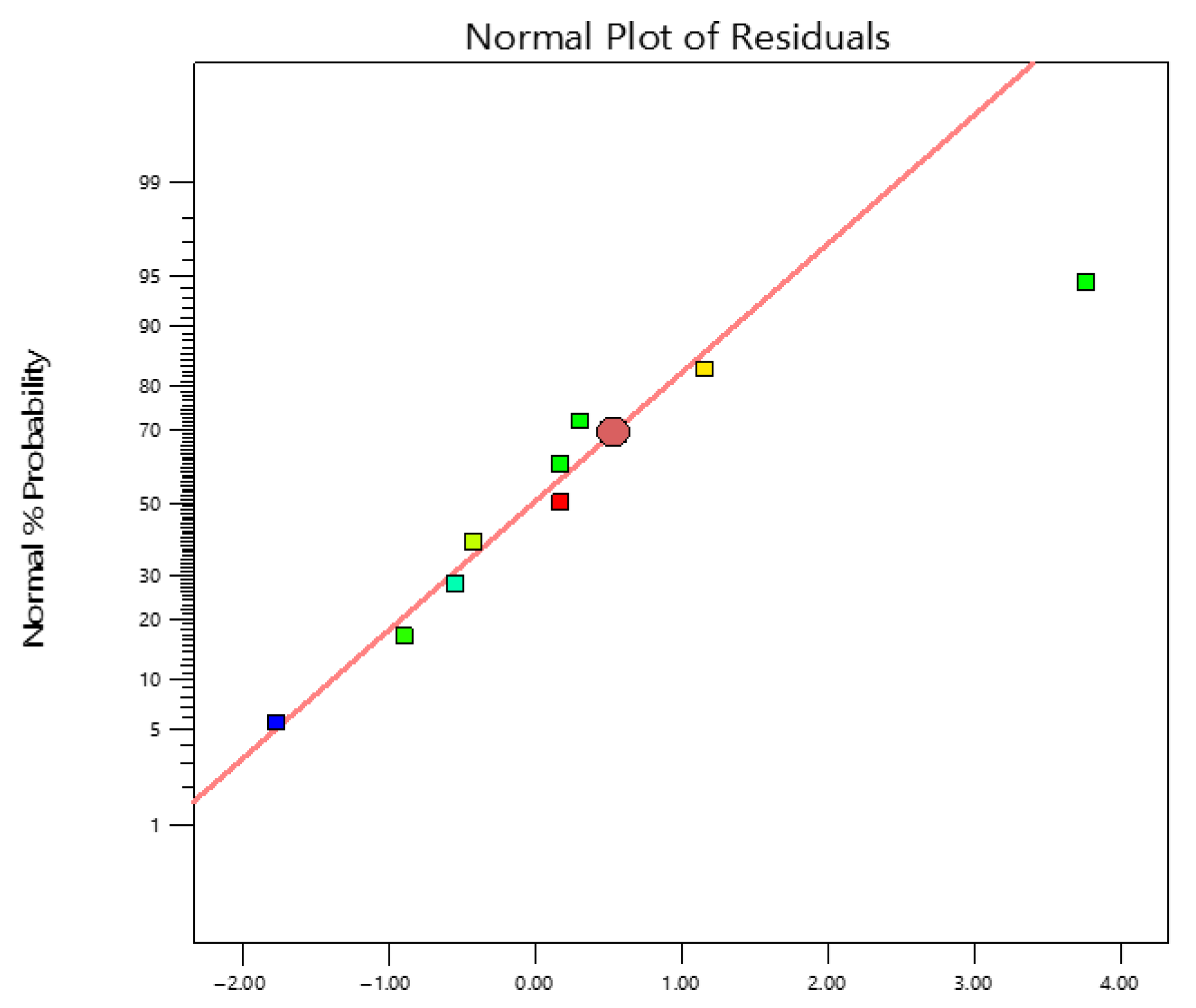

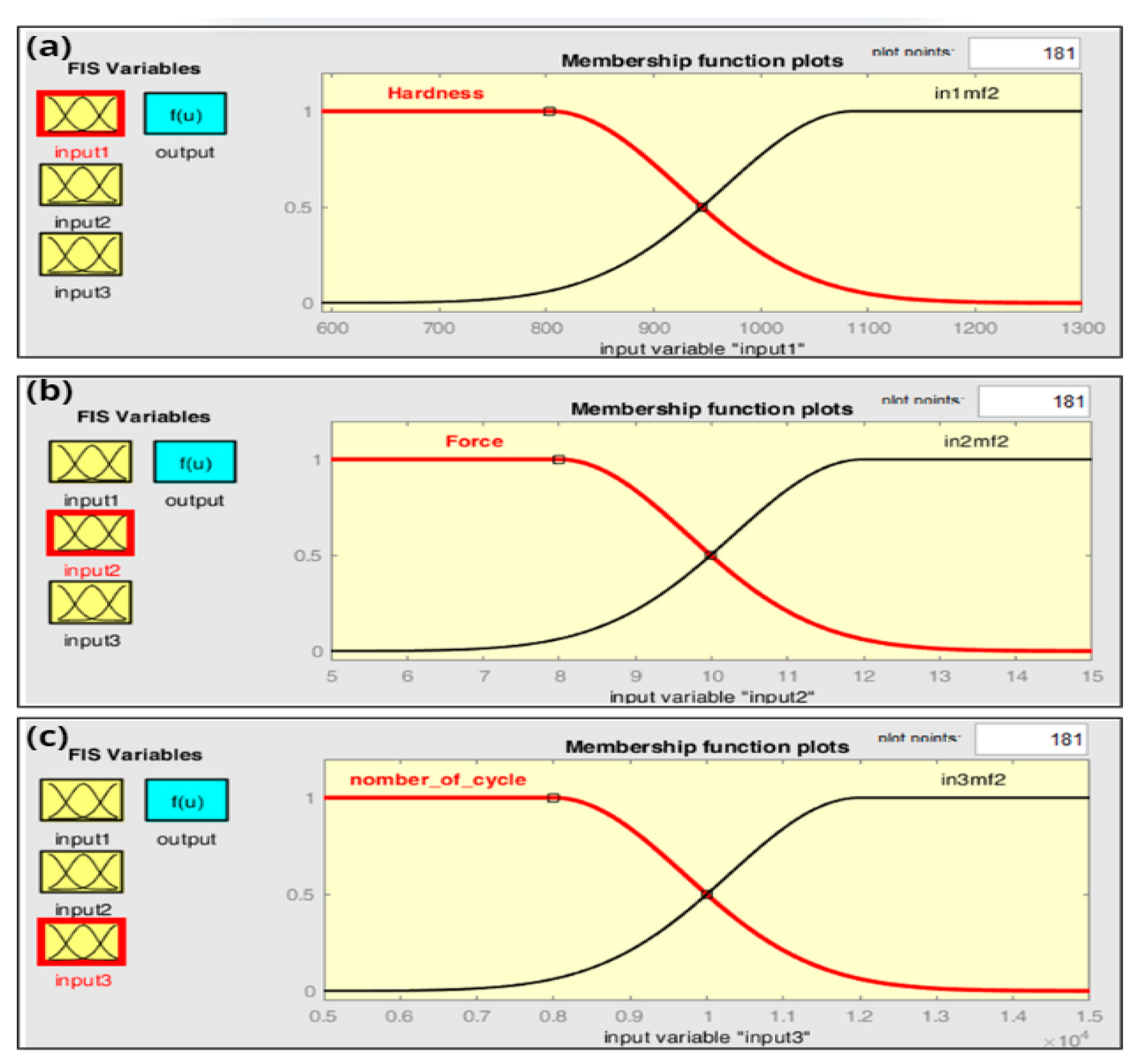

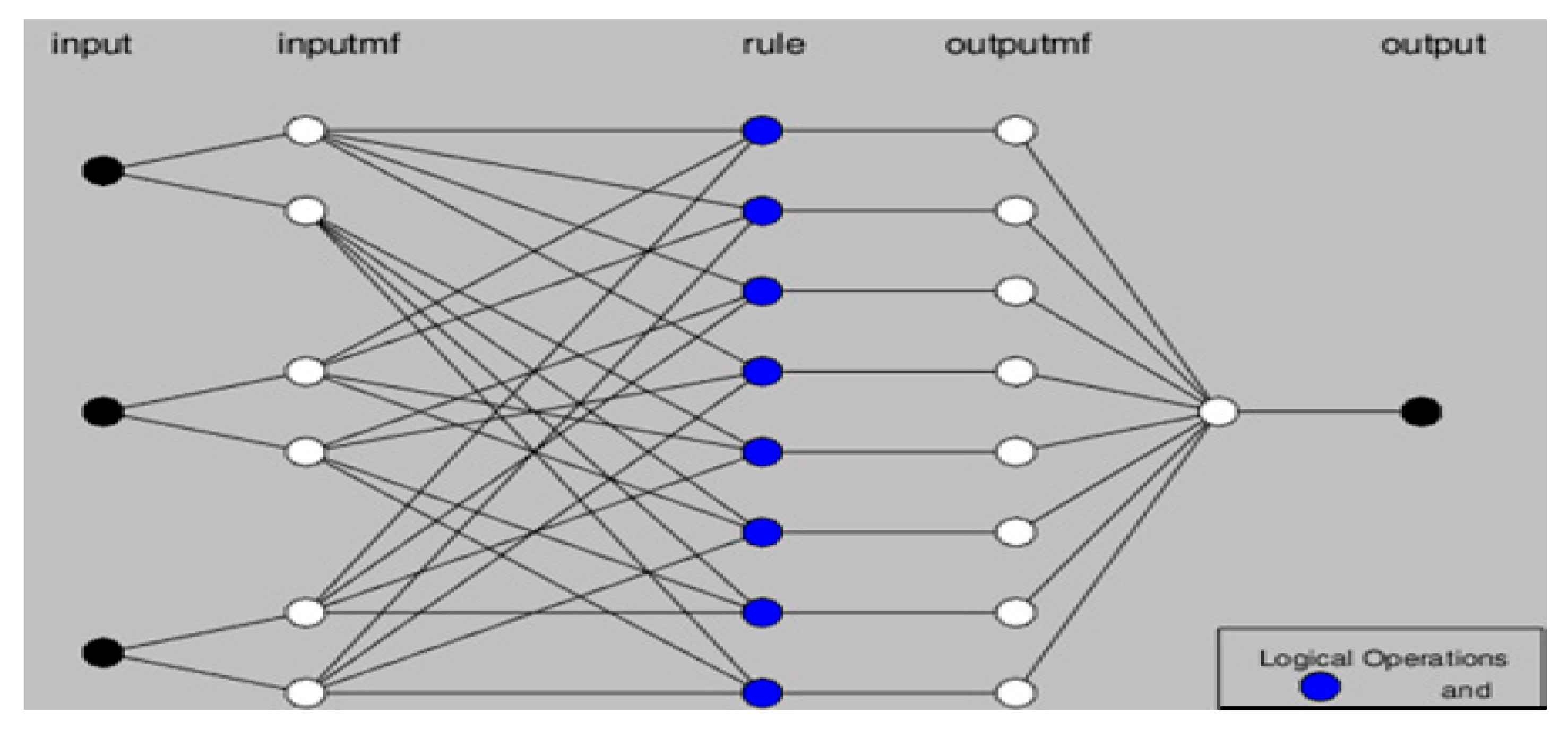

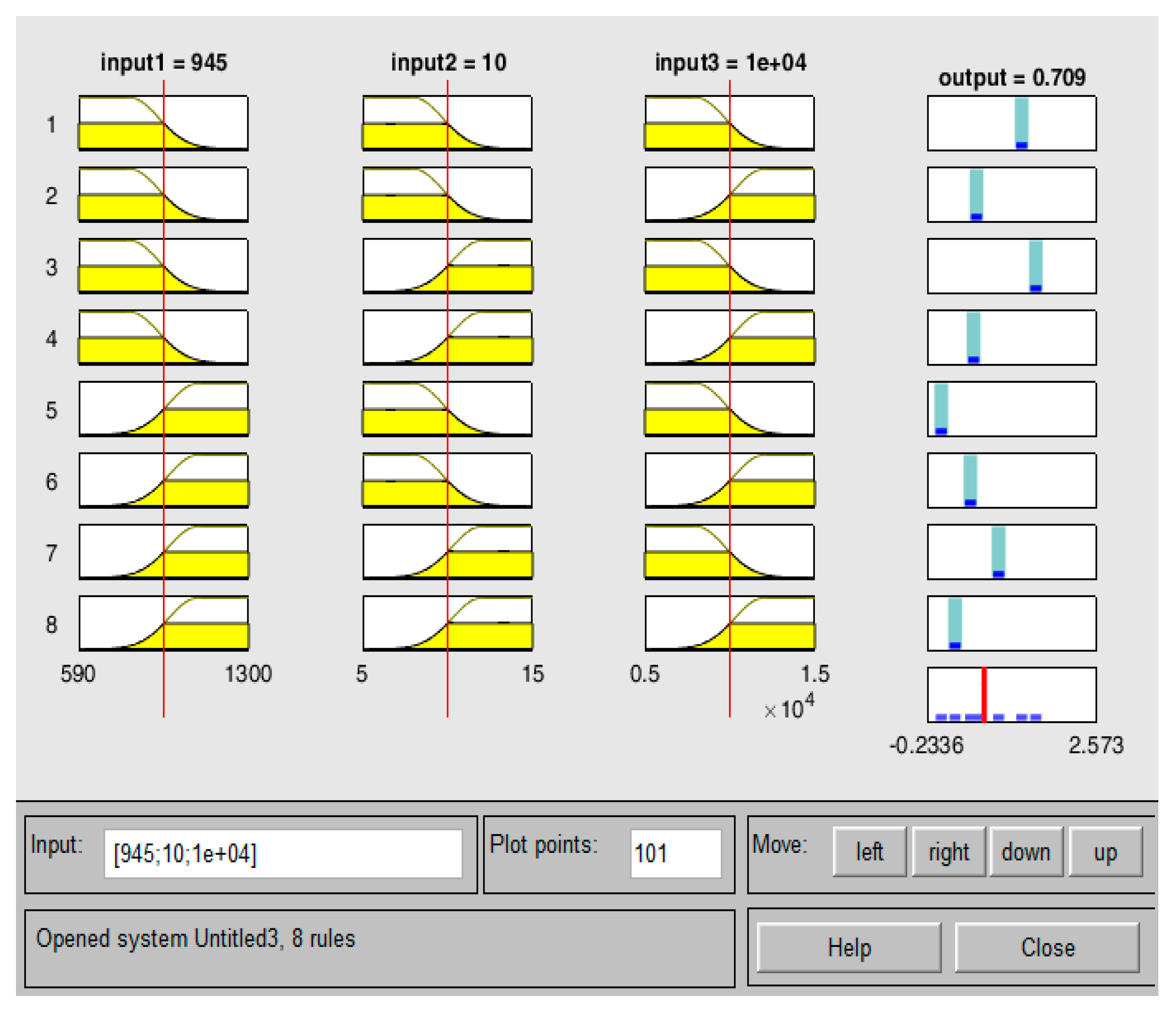

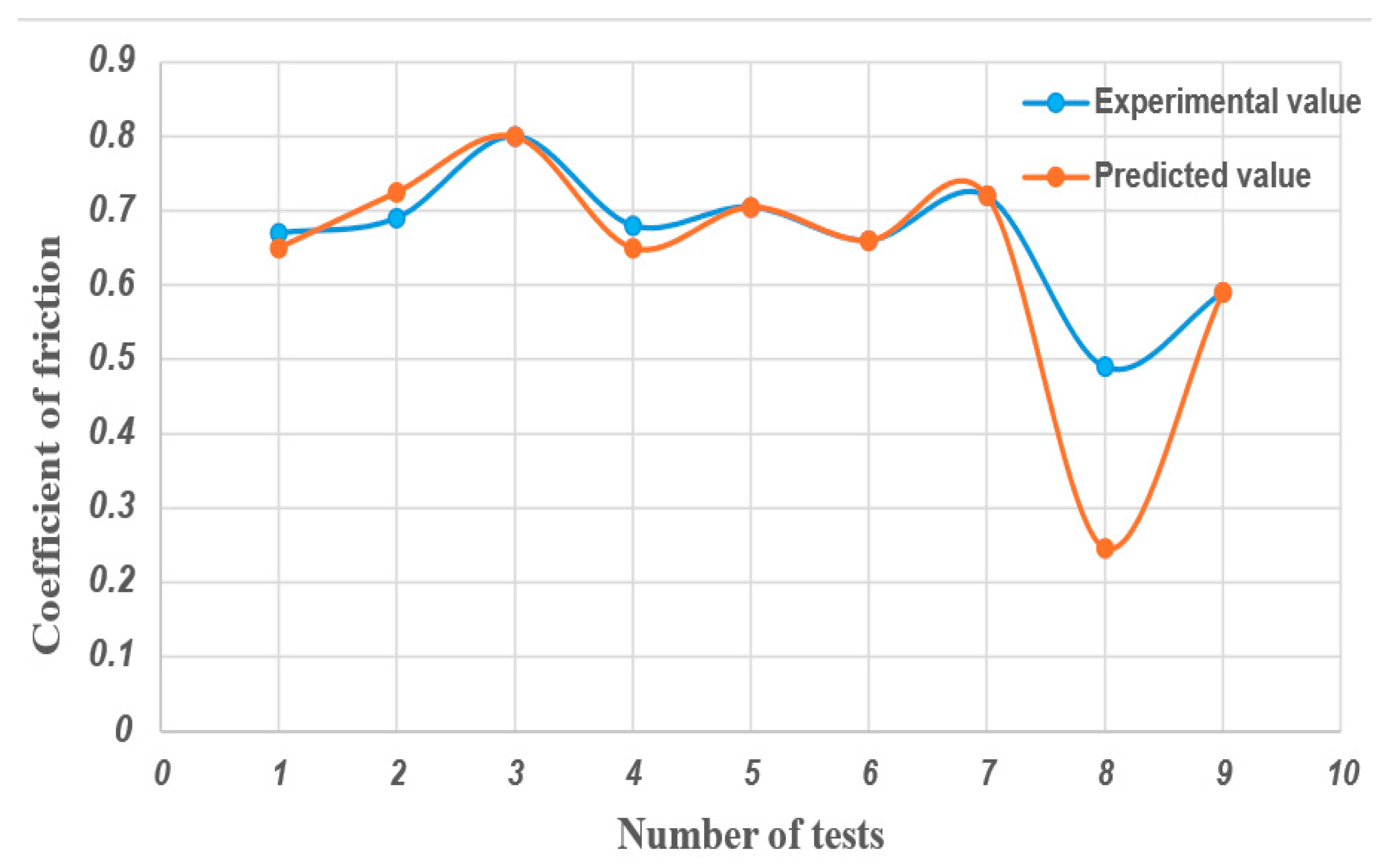

3.6. Prediction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- It has been shown that the surface hardness properties of the layers formed during nitriding have a significant influence on the COF.

- -

- It has been shown that longer nitriding times result in a lower COF. Specifically, this coefficient is reduced to around 0.59 for a nitriding time of 16 h (N16) and to around 0.49 for 36 h (N36), compared with around 0.67 for non-nitrided steel.

- -

- Analysis of the wear test results shows that the normal load applied has a significant impact on the COF, whether the material is treated or untreated steel.

- -

- A detailed study revealed that 36 h of nitriding (N36) induces a more significant variation in the COF than 16 h of nitriding (N16). This variation is a function of the number of cycles performed.

- -

- In order to achieve a substantial reduction in the COF of D2 steel, it is recommended to extend the nitriding time beyond 16 h.

- -

- The nitriding treatment is capable of reducing the friction coefficient by approximately 39%.

- -

- The study revealed that the main factors determining the COF are processing parameters, such as surface hardness and normal load, as well as the number of cycles. ANFIS identified these complex relationships with remarkable efficiency, highlighting the importance of these variables in optimizing tribological performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rehman, H.U.; Naeem, M.; Abrar, M.; Shafiq, M.; Díaz-Guillén, J.; Yasir, M.; Mahmood, S. Enhancement of hardness and tribological properties of AISI 321 by cathodic cage plasma nitriding at various pulsed duty cycle. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.T.; Song, K.; Oh, S.H.; Lee, Y.K.; Lee, W.B. Enhanced surface hardening of AISI D2 steel by atomic attrition during ion nitriding. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2014, 251, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafizadeh, M.; Ghasempour-Mouziraji, M.; Sadeghi, B.; Cavaliere, P. Characterization of Tribological and Mechanical Properties of the Si3N4 Coating Fabricated by Duplex Surface Treatment of Pack Siliconizing and Plasma Nitriding on AISI D2 Tool Steel. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2021, 52, 4753–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terres, M.A.; Sidhom, H.; Larbi, A.B.C.; Ouali, S.; Lieurade, H.P. Influence de la résistance à la fissuration de la couche de combinaison sur la tenue en fatigue des composants nitrurés. Matériaux Tech. 2001, 89, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M.L.; Recco, A.A.C. Duplex treatment on AISI D2 tool steel: Plasma nitriding and reactive deposition of TiN and TiAlN films via magnetron sputtering. Rev. Mater. 2022, 27, e20220111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conci, M.D.; Bozzi, A.Ô.C.; Franco, A.R. Effect of plasma nitriding potential on tribological behaviour of AISI D2 cold-worked tool steel. Wear 2014, 317, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, K.; Karabeyoğlu, S.S.; Yaman, P. Effect of nitriding conditions and operation temperatures on dry sliding wear properties of the aluminum extrusion die steel in the industry. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.T.; Lee, Y.K.; Lee, W.B. Wear behavior of AISI D2 steel by enhanced ion nitriding with atomic attrition. Tribol. Int. 2015, 87, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terres, M.A.; Bechouel, R.; Mohamed, S.B. Low Cycle Fatigue Behavior of Nitrided Layer of 42CrMo4 Steel. Int. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 6, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yarasu, V.; Jurci, P.; Hornik, J.; Krum, S. Optimization of cryogenic treatment to improve the tribological behavior of Vanadis 6 steel using the Taguchi and grey relation approach. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 2945–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, P.; Bergelt, T.; Rymer, L.-M.; Kipp, C.; Grund, T.; Bräuer, G.; Lampke, T. Evolution of Microstructure and Hardness of the Nitrided Zone during Plasma Nitriding of High-Alloy Tool Steel. Metals 2022, 12, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapici, A.; Aydin, S.E.; Koc, V.; Kanca, E.; Yildiz, M. Wear Behavior of Borided AISI D2 Steel under Linear Reciprocating Sliding Conditions. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2019, 55, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphonse, M.; Bupesh Raja, V.K.; Gupta, M. Optimization of plasma nitrided, liquid nitrided & PVD TiN coated H13-D2 friction drilling tool on AZ31B magnesium alloy. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 46, 9520–9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Guillén, J.C.; Alvarez-Vera, M.; Díaz-Guillén, J.A.; Acevedo-Davila, J.L.; Naeem, M.; Hdz-García, H.M.; Granda-Gutiérrez, E.E.; Muñoz-Arroyo, R. A Hybrid Plasma Treatment of H13 Tool Steel by Combining Plasma Nitriding and Post-Oxidation. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2018, 27, 6118–6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, D.; Guo, Y.; Liu, S. Friction and wear behaviors of sand particle against casing steel. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2019, 233, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, I.M.; Pascu, A.; Hulka, I.; Woelk, D.H.; Uțu, I.D.; Mărginean, G. Characterization of Cobalt-Based Composite Multilayer Laser-Cladded Coatings. Crystals 2025, 15, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Qu, S.; Jia, S.; Li, X. Evolution of wear damage in gross sliding fretting of a nitrided high-carbon high-chromium steel. Wear 2021, 464–465, 203548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, W.; Hu, H.; Cai, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, G. The corrosion and wear behaviors of a medium-carbon bainitic steel treated by boro-austempering process. Metals 2021, 11, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix-Martínez, C.; García-Salas, L.D.; González-Carmona, J.M.; Ruiz-Luna, H.; García-Moreno, Á.I.; Alvarado-Orozco, J.M. Microstructure, hardness, and tribological performance of D2 tool steel fabricated by laser cladding using pulsed wave and substrate heating. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 175, 110862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş Çelik, G.; Yarar, E.; Atapek, H.; Polat, Ş. Prediction of contact stress and wear analysis of nitrided and CAPVD coated AISI H11 steel under dry sliding conditions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 165, 108738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Guillén, J.C.; Naeem, M.; Hdz-García, H.; Acevedo-Davila, J.; Díaz-Guillén, M.; Khan, M.; Iqbal, J.; Mtz-Enriquez, A. Duplex plasma treatment of AISI D2 tool steel by combining plasma nitriding (with and without white layer) and post-oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 385, 125420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabak, Y.; Efremenko, V.; Barma, Y.; Petrišinec, I.; Efremenko, B.; Kromka, F.; Sili, I.; Kovbasiuk, T. Enhancing Dry-Sliding Wear Performance of a Powder-Metallurgy-Processed “Metal Matrix–Carbide” Composite via Laser Surface Modification. Eng 2025, 6, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamboiki, C.M.; Mourlas, A.; Psyllaki, P.; Sideris, J. Influence of microstructure on the sliding wear behavior of nitro-592 carburized tool steels. Wear 2013, 303, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaba, M.; Filiz, H.I.; Cui, Z.; Baydogan, M.; Cimenoglu, H.; Alpas, A.T. Microstructural effects on impact-sliding wear mechanisms in D2 steels: The roles of matrix hardness and carbide characteristics. Wear 2024, 538–539, 205224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitao, S.; Bin, W.; Xiaoliang, L.; Yuqian, W.; Jian, Z. Controlling the tribology performance of gray cast iron by tailoring the microstructure. Tribol. Int. 2022, 167, 107343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghbouch, A.; Terres, M.A. Optimization of Mass Loss During Abrasive Wear of Nitrided AISI 4140 Steel Parts. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. In Design and Modeling of Mechanical Systems—VI; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, K.; Walczak, M.; Szala, M.; Gancarczyk, K. Tribological behavior of alcrsin-coated tool steel k340 versus popular tool steel grades. Materials 2020, 13, 4895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghajani Derazkola, H.; Fauconnier, D.; Kalácska, Á.; Garcia, E.; Murillo-Marrodán, A.; De Baets, P. Tribological behaviour of DIN 1.2740 hot working tool steel during mandrel mill stretching process. Tribol. Int. 2025, 202, 110361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, F.; Zhu, D.; Ji, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. Relationship between discoloration, condensation, and tribology behavior of steel surfaces at cryogenics in vacuum. Tribol. Int. 2024, 191, 109104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, B.B.; Kumar, V.; Sahoo, S.; Oraon, B.; Mukherjee, S. Nanoparticle-Reinforced Electroless Composite Coatings for Pipeline Steel: Synthesis and Characterization. Materials 2025, 18, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhadilov, B.; Satbayeva, Z.; Maulit, A.; Kadyrbolat, N.; Rustemov, A. Electrolytic-Plasma Nitriding of Austenitic Stainless Steels After Mechanical Surface Treatment. Crystals 2025, 15, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Que, B.; Dong, L.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X. Unraveling the Friction and Wear Mechanisms of a Medium-Carbon Steel with a Gradient-Structured Surface Layer. Lubricants 2025, 13, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, P. Hybrid GA-ANN and GA-ANFIS soft computing approaches for optimizing tensile strength in magnesium-based composites fabricated via friction stir processing. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 44, 112083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivarajan, S.; Elango, M.; Sasikumar, M.; Doss, A.S.A. Prediction of surface roughness in hard machining of EN31 steel with TiAlN coated cutting tool using fuzzy logic. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngerntong, S.; Butdee, S. Surface roughness prediction with chip morphology using fuzzy logic on milling machine. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 26, 2357–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazani, M.R.C.; Pourmostaghimi, V.; Moayyedian, M.; Pedrammehr, S. Estimation of tool–chip contact length using optimized machine learning in orthogonal cutting. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 114, 105118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Designation | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Mo | V | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AISI D2 | 1.55 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.023 | 0.003 | 11.6 | 0.74 | 0.92 | Bal. |

| Hardness (HV0.1) | Force (N) | Number of Cycles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 560 | 5 | 5000 |

| Level 2 | 1100 | 10 | 10,000 |

| Level 3 | 1350 | 15 | 15,000 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.0484 | 3 | 0.0161 | 6.17 | 0.0392 | Significant |

| A—Hardness | 0.0189 | 1 | 0.0189 | 7.21 | 0.0436 | |

| B—Force | 0.0002 | 1 | 0.0002 | 0.0573 | 0.8203 | |

| C—Number of cycles | 0.0294 | 1 | 0.0294 | 11.24 | 0.0203 | |

| Residual | 0.0131 | 5 | 0.0026 | |||

| Cor Total | 0.0615 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Souid, A.; Mzali, S.; Louhichi, B.; Terres, M.A. Enhancement of Wear Behaviour and Optimization and Prediction of Friction Coefficient of Nitrided D2 Steel at Different Times. Lubricants 2025, 13, 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120550

Souid A, Mzali S, Louhichi B, Terres MA. Enhancement of Wear Behaviour and Optimization and Prediction of Friction Coefficient of Nitrided D2 Steel at Different Times. Lubricants. 2025; 13(12):550. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120550

Chicago/Turabian StyleSouid, Abdallah, Slah Mzali, Borhen Louhichi, and Mohamed Ali Terres. 2025. "Enhancement of Wear Behaviour and Optimization and Prediction of Friction Coefficient of Nitrided D2 Steel at Different Times" Lubricants 13, no. 12: 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120550

APA StyleSouid, A., Mzali, S., Louhichi, B., & Terres, M. A. (2025). Enhancement of Wear Behaviour and Optimization and Prediction of Friction Coefficient of Nitrided D2 Steel at Different Times. Lubricants, 13(12), 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120550