1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Conditions such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, and hypertension frequently result in vascular stenosis or occlusion, posing serious threats to patient health and quality of life. With the rapid aging of the global population and shifts in lifestyle patterns, the incidence of these diseases continues to increase [

1]. Globally, cardiovascular diseases account for more than 15 million deaths annually, a number that continues to rise and is projected to exceed 23.6 million by 2030 [

2]. In China alone, cardiovascular diseases are responsible for over 4.3 million deaths each year—nearly one-third of the global total—highlighting an urgent challenge for national public health management and disease prevention strategies [

3].

Vascular grafting or bypass surgery has become an essential intervention for restoring blood flow and improving clinical outcomes in various surgical procedures. Clinical scenarios such as revascularization surgeries and the establishment of dialysis access urgently require reliable and durable vascular substitutes [

4]. Currently, autologous vessels and synthetic grafts remain the most commonly used options in clinical practice. Although autologous vessels—such as the great saphenous vein, radial artery, and internal mammary artery—are considered the “gold standard,” their broader applicability is limited by factors including restricted donor availability, additional trauma associated with vessel harvesting, and variability in donor vessel quality. These limitations are particularly pronounced in patients with severe trauma, those undergoing complex reoperations, or individuals with widespread vascular disease [

5].

Small-diameter vascular grafts (SDVGs), typically defined as vascular substitutes with an inner diameter ≤ 6 mm, have long posed challenges in vascular graft research. Compared to large-diameter grafts, SDVGs carry a higher risk of early- and mid-term clinical failure. Common failure mechanisms include thrombus formation, restenosis due to intimal hyperplasia, and mechanical mismatch with host vessels. These issues not only affect short-term patency rates but also limit the clinical adoption of novel materials and strategies [

6]. Achieving favorable hemocompatibility and endothelialization while maintaining mechanical performance is the current research focus and major challenge [

7].

In recent years, the interdisciplinary advancement of technologies such as materials science, tissue engineering, biomanufacturing, and surface functionalization has brought new hope for addressing the critical bottlenecks in SDVGs [

8]. Representative advances include biomimetic structural designs based on electrospun nanofibers and composite scaffolds [

9]; “in vivo regeneration” strategies combining degradable scaffolds with host regeneration [

10]; early clinical applications of decellularized matrices and acellular tissue-engineered vessels (ATEV) [

11]; and multifunctional surface modifications targeting endothelialization and anti-thrombosis [

12] (e.g., heparinization, NO release). Early clinical/preclinical data indicate encouraging short-term patency rates for certain bioengineered grafts, though long-term follow-up remains insufficient. Challenges persist in manufacturing reproducibility, cost-effectiveness, and regulatory pathways [

12].

Against this backdrop, this review focuses on small-diameter vascular grafts (SDVGs) and provides a comprehensive overview of their design principles, material selection, failure mechanisms, and the current progress and challenges associated with their clinical application. The objective is to synthesize recent research advancements, identify existing technical and translational bottlenecks, and highlight potential future development directions. Through this analysis, the review aims to offer valuable references and insights for researchers and practitioners working in the field of vascular tissue engineering.

2. Failure Mechanisms of Small-Diameter Artificial Blood Vessels

The development of small-diameter artificial blood vessels (diameter < 6 mm) stems from urgent clinical demand. The high global prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, particularly coronary artery disease and peripheral artery disease, creates a substantial demand for vascular replacement surgery [

1]. However, in clinical practice, autologous vascular resources are limited, and not all patients are suitable or eligible for autologous transplantation. For instance, some patients suffer from insufficient available vessels due to varicose veins, diabetic complications, or prior multiple surgeries [

13]. Therefore, identifying ideal small-diameter artificial vascular materials is crucial to addressing this challenge.

Although large-diameter artificial vessels have demonstrated relatively satisfactory long-term patency in clinical applications, their performance declines markedly when the graft diameter is reduced to less than 6 mm [

14]. Extensive clinical and experimental evidence suggests that the major challenges associated with small-diameter artificial vessels are primarily concentrated in the following aspects:

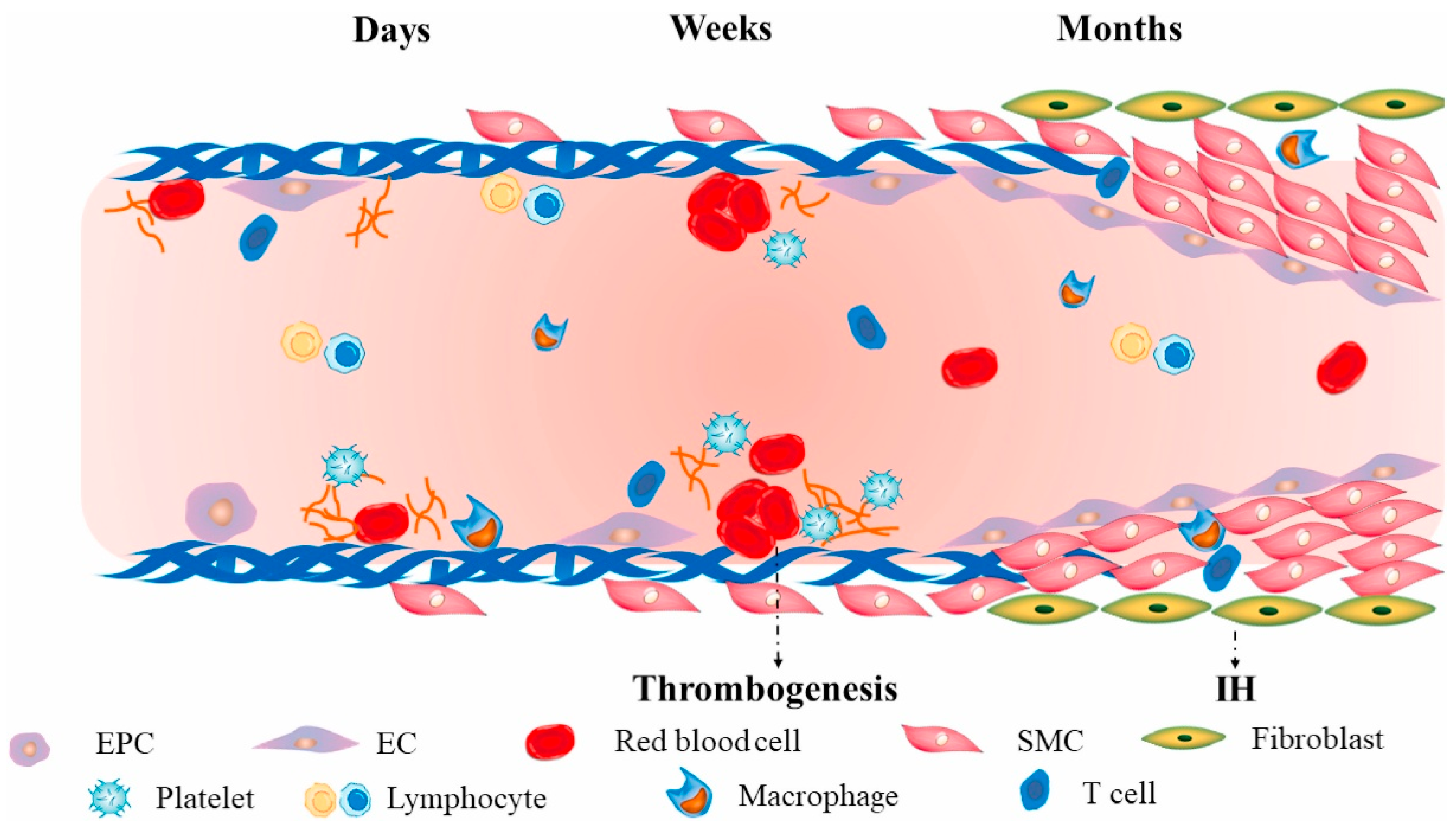

First, thrombosis is the primary cause of failure in small-diameter artificial blood vessels: Unlike large-diameter grafts, which exhibit high blood flow velocity and low resistance at the implantation site, small-diameter grafts experience slowed blood flow. Additionally, the artificial material surface readily triggers a coagulation cascade upon contact with blood, making it more susceptible to early thrombotic occlusion [

15]. Enhancing blood compatibility while reducing protein adsorption and platelet adhesion remains an urgent challenge [

16] (

Figure 1).

Secondly, intimal hyperplasia and restenosis significantly impact long-term vascular patency rates. Mechanical mismatch between the graft and host vessels, particularly differences in compliance, readily induces abnormal turbulence and shear stress at the anastomotic site. This stimulates excessive proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells, leading to neointimal formation and luminal narrowing [

17].

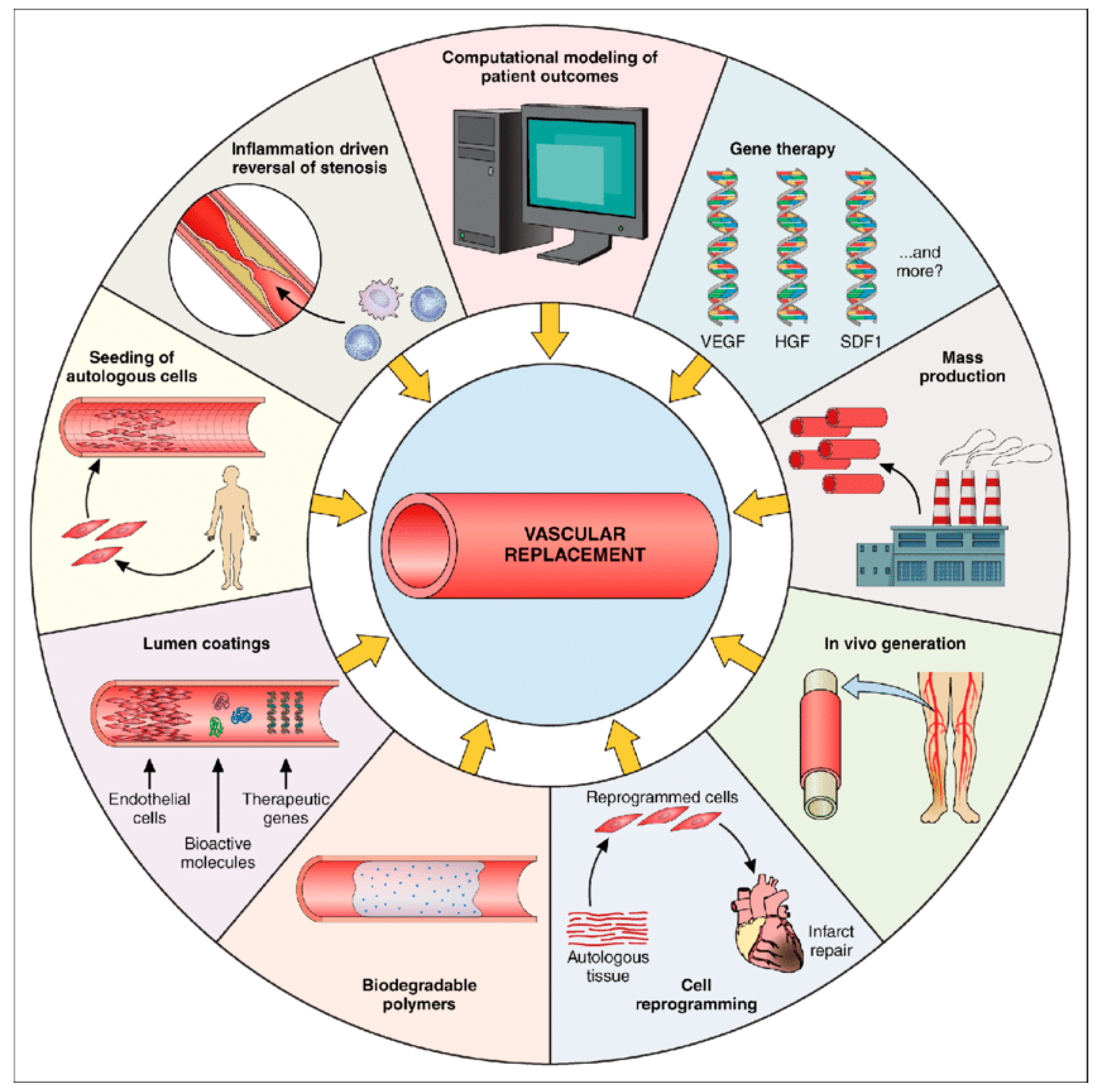

Thirdly, insufficient biocompatibility also constitutes a significant constraint on its development. An ideal artificial blood vessel should possess favorable cell adhesion and proliferation properties, enabling rapid endothelial cell coverage to form a stable endothelialized intima and reduce thrombosis risk [

18]. However, most synthetic materials lack biological activity, making complete endothelialization difficult to achieve [

19] (

Figure 2).

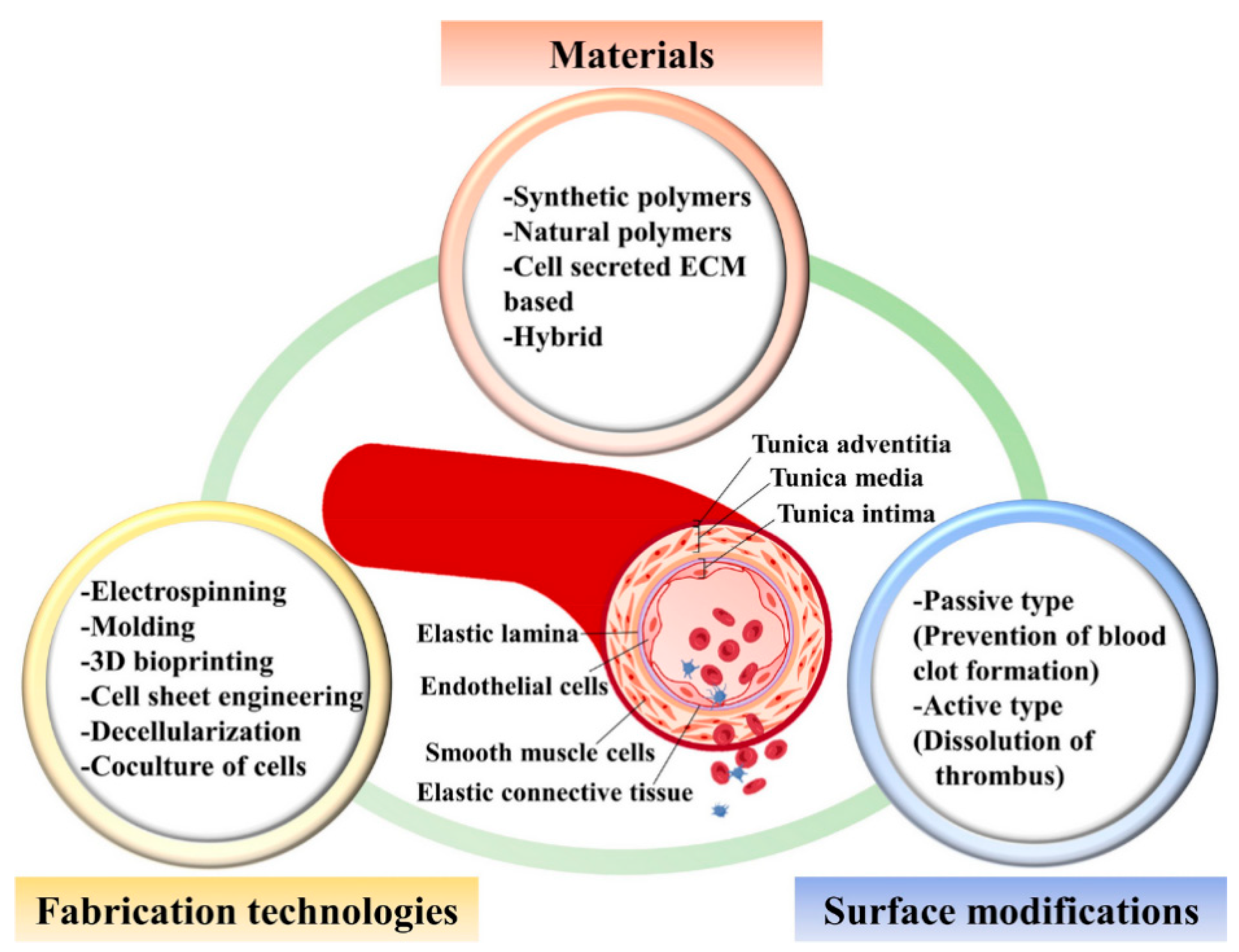

Furthermore, the risks of infection and chronic inflammation cannot be overlooked. Following implantation of small-diameter artificial blood vessels, host immune reactions and material degradation byproducts may induce chronic inflammation, increasing the risk of graft failure [

20] (

Figure 3). This issue is particularly pronounced in patients with diabetes or compromised immune function.

In summary, a significant gap exists between the urgent clinical demand for small-caliber artificial blood vessels and their current limitations in blood compatibility, mechanical performance, and long-term patency. This disparity has stimulated continuous research efforts across multiple disciplines, including materials science, tissue engineering, surface modification strategies, and advanced manufacturing technologies.

3. Material Modification Strategies for Improving Thrombosis Formation

Small-diameter artificial blood vessels are in prolonged contact with blood, and their interface properties directly determine blood compatibility and early patency rates. Traditional inert materials like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and polyester (PET) perform well in large-diameter vessels but are prone to thrombosis and luminal occlusion in small-diameter conditions [

21]. Therefore, surface modification to regulate material wettability, charge distribution, microstructure, and interfacial energy has become a key approach to enhancing the antithrombotic properties of small-diameter artificial blood vessels [

20].

3.1. Surface Hydrophilic Modification

Upon contact with blood, the initial process occurring on the material surface is protein adsorption. The adsorption rate and protein conformational changes directly influence subsequent platelet adhesion and the coagulation cascade. Research indicates that enhancing the material’s surface hydrophilicity can form a stable hydration layer, thereby reducing protein adsorption and lowering the risk of platelet activation [

22]. Common hydrophilic modification methods include:

Polyethylene glycol (PEG): PEG is a polymeric material characterized by exceptional hydrophilicity and biological inertness. Due to its non-immunogenic nature and ability to form stable hydration layers with water molecules, PEG effectively suppresses non-specific protein adsorption, prevents conformational changes in plasma proteins (such as fibrinogen), thereby reducing platelet adhesion and activation, and helps maintain the natural activity of proteins. For this reason, PEG is widely used to enhance the hemocompatibility of biomaterials [

23].

Dimitrievska et al. [

24] used polyethylene terephthalate (PET) as the substrate and employed polyethyleneamine as the crosslinking agent to graft PEG at different concentrations onto its surface. Results showed that at a PEG concentration of 10%, platelet adhesion was only 3900 platelets/mm

2, approximately one-seventh of the bovine collagen-coated polyester group. Adhered platelets predominantly exhibited inactive circular or disc-shaped morphology, indicating that PEG grafting significantly suppressed platelet activation. Another study by Dai et al. [

25] demonstrated that introducing PEG into argatroban-fixed membranes further inhibited platelet adhesion and activation, prolonged clotting time, and reduced thrombin generation and complement system activation, exhibiting excellent anticoagulant properties.

However, with the widespread use of PEG in food, pharmaceuticals, and medical products, concerns about its potential immunogenicity have emerged in recent years. Studies have detected a high prevalence of anti-PEG IgM and IgG antibodies in plasma from healthy blood donors in the United States. Among the five PEG-related allergy cases reported by Sellaturay et al. [

26] in 2021, one patient experienced a severe allergic reaction leading to cardiac arrest. Thus, despite PEG modification’s significant advantages in improving blood compatibility, its clinical safety remains a concern. Artificial vascular materials containing PEG components still require further validation of their long-term biocompatibility through systematic experimental and clinical studies [

27].

Poloxamer blend: Poloxamer consists of two hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG) units and one hydrophobic polypropylene glycol (PPG) unit, forming a linear triblock structure (PEGx–PPGy–PEGx). Its hydrophobic segments anchor to the material backbone, causing the hydrophilic side chains to migrate to the surface, thereby effectively inhibiting protein adsorption and platelet adhesion. LE et al. [

28] blended poloxamer into polyurethane/polycaprolactone electrospun scaffolds. Results showed that increasing poloxamer concentration by 1% reduced platelet adhesion by over 10%. When the mass fraction exceeded 8%, platelet rejection exceeded 70%, with adhered platelets predominantly in an inactivated state. Research also revealed that adding poloxamer to culture medium enhanced the viability and proliferation of colon cancer Caco-2 cells. PAZHANIMALA et al. [

29] incorporated poloxamer into polycaprolactone/gelatin blended scaffolds. They observed that optimal addition (PCL/gelatin/poloxamer ratio of 80:10:10) significantly promoted Caco-2 cell proliferation. However, systematic studies on the effects of poloxamer content and culture duration on endothelial cell proliferation remain lacking.

Glycerol decanedioate and amphoteric polymers: Poly(glycerol decanedioate) (PGS) is a biodegradable elastic polyester formed by the polycondensation of glycerol and decanedioic acid. Due to its hydrophobic fatty ester backbone, its surface readily adsorbs plasma proteins and platelets, necessitating hydrophilic modification to enhance blood compatibility. Common modification methods include grafting hydrophilic polymers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), plasma oxidation treatment, blending with hydrophilic polymers, or biomolecular modification [

30]. The mechanism primarily involves introducing polar functional groups (e.g., –OH, –COOH) or hydrophilic segments to form a stable hydration layer on the surface. This effectively shields hydrophobic interactions, inhibits non-specific protein adsorption and platelet adhesion, and reduces the risk of thrombosis. Simultaneously, hydrophilic modification increases surface free energy, improves wettability, and promotes cell adhesion and proliferation, thereby significantly enhancing the material’s biocompatibility and tissue integration capabilities [

31].

However, while highly hydrophilic surfaces can significantly inhibit thrombus formation, they may restrict endothelial cell adhesion and growth, hindering the completion of the endothelialization process. Therefore, the design must strike a balance between anticoagulant properties and biological activity, enabling the material to suppress thrombus formation while maintaining cell-friendly characteristics.

3.2. Surface Charge and Topological Structure Modulation

Platelet adhesion is influenced not only by the chemical composition of a material but also by its surface charge distribution and topographical features. When a biomaterial comes into contact with blood, the initial event is the adsorption of plasma proteins, whose types, conformations, and orientations subsequently determine platelet recognition and activation. Therefore, by precisely modulating surface charge and micro/nanotopography, the hemocompatibility of vascular graft materials can be effectively regulated.

Regarding charge regulation, studies indicate that the charged state of material surfaces can significantly alter the adsorption selectivity and conformational stability of plasma proteins. For instance, Tzoneva et al. [

32] discovered that grafting carboxyl and sulfonic acid groups onto polyurethane surfaces effectively reduced fibrinogen adsorption and conformational changes on weakly negatively charged surfaces, thereby lowering platelet activation rates. Conversely, positively charged surfaces more readily adsorb negatively charged proteins such as fibrinogen and immunoglobulins, thereby triggering the coagulation cascade. Research by Nagaoka and Kimura [

33] further indicates that moderate negative charge helps inhibit prothrombin fragment conversion, significantly prolonging plasma clotting time.

Common surface modification techniques include plasma treatment, sol–gel methods, and layer-by-layer (LbL) self-assembly. These approaches enable the introduction of functional groups such as carboxyl, sulfonic acid, amine, or quaternary ammonium groups onto material surfaces to regulate surface potential. For example, Jung et al. [

34] employed LbL technology to alternately assemble negatively charged hyaluronic acid (HA) and positively charged chitosan (CS) on the surface of polylactic acid (PLA). The results demonstrated that this bilayer structure effectively inhibited platelet adhesion while maintaining good endothelial cell adhesion, achieving a synergistic “antithrombotic–proendothelial” effect.

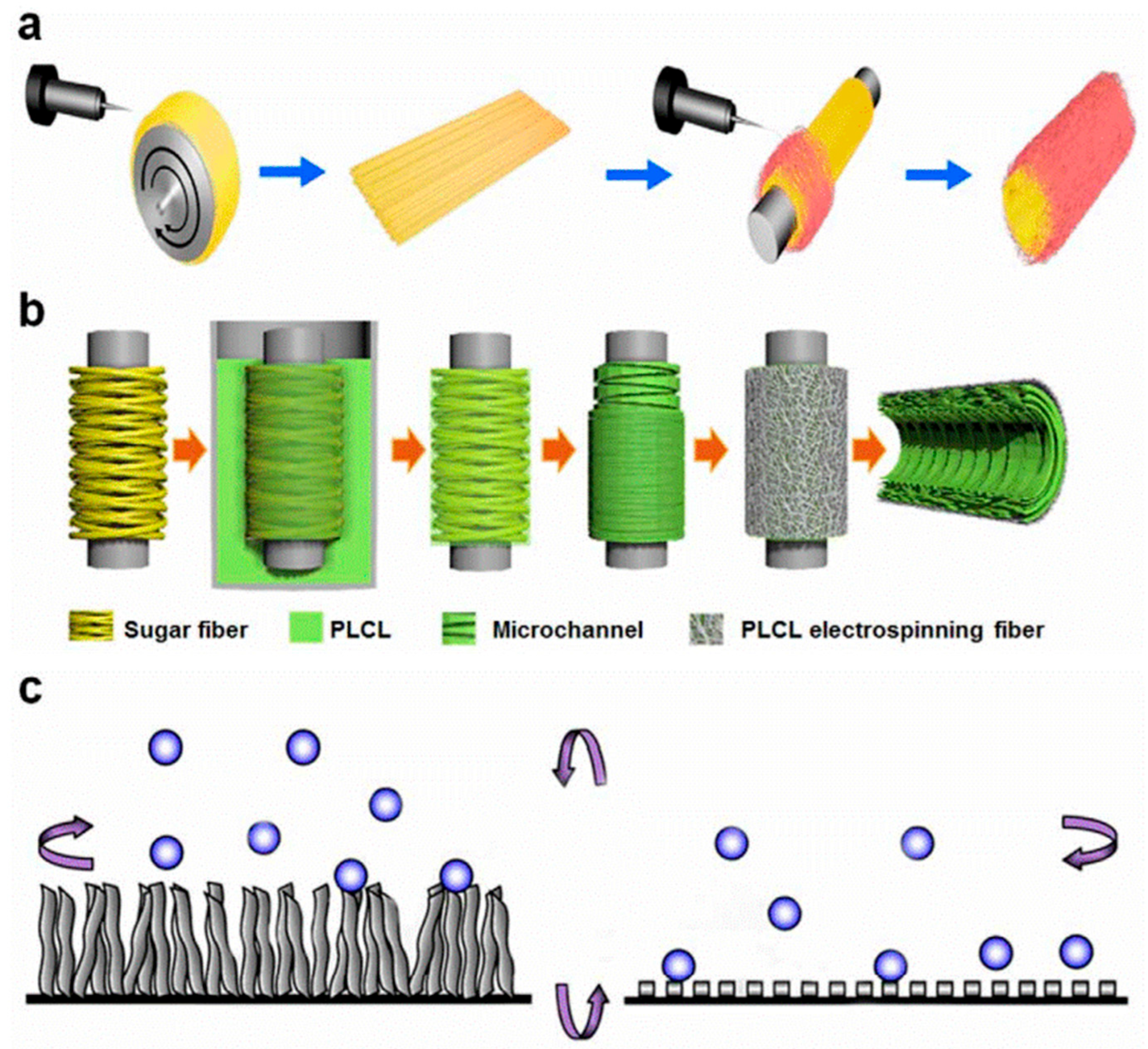

Regarding surface morphology, the micro- and nanostructures of materials can significantly influence the distribution of blood flow shear stress and cellular mechanical responses. Studies indicate that nanoscale roughness reduces platelet deformation, maintaining their spherical shape and minimizing pseudopod extension, thereby placing them in a “deactivated” state. Cheng et al. [

35] constructed 50–100 nm scale nano-roughness on polycaprolactone (PCL) surfaces, observing a 60% reduction in platelet adhesion while enhancing the spreading rate of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) on this surface. Conversely, micrometer-scale irregular structures promote mechanical anchoring and cytoskeletal reorganization in endothelial cells, thereby enhancing cell migration and integration.

Additionally, Xue et al. [

36] employed laser etching technology to construct biomimetic shark skin microstructures on polyimide (PI) surfaces, simulating the microtexture features of natural vascular endothelium. Results demonstrated that platelet adhesion on these surfaces was only 25% of that on smooth surfaces, while endothelial cell proliferation increased by 1.8 times. This type of biomimetic topological design offers a novel approach for achieving “selective interfaces” in artificial vascular materials.

Therefore, by comprehensively regulating surface charge and topological structure, a balance can be achieved between antithrombotic properties and endothelialization performance. This strategy, shifting from “chemical regulation” to “multidimensional interface engineering,” has become a significant trend in the design of artificial blood vessels and blood-contacting materials. Future research may further integrate precise charge-mapping modeling with high-resolution microstructural control to explore the coupling mechanisms among charge, morphology, and biological responses, thereby enabling predictable, controllable blood-compatibility design [

37] (

Figure 4).

3.3. Introduction of Antibacterial and Anti-Inflammatory Functions

Thrombosis frequently accompanies localised inflammatory responses and poses a potential infection risk. Once bacterial colonisation occurs on artificial blood vessels or blood-contacting materials, it not only leads to implant failure but may also trigger platelet aggregation and secondary thrombosis by inducing the release of inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, incorporating antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties into material design has become a key strategy for enhancing blood compatibility.

3.3.1. Antimicrobial Function Introduction Strategy

Antimicrobial Metal Ion Modification: Metal ions such as silver (Ag

+), copper (Cu

2+), and zinc (Zn

2+) exhibit broad-spectrum antibacterial properties. Silver ions bind to bacterial cell wall proteins and DNA, disrupting cellular metabolism; copper ions induce lipid peroxidation in cell membranes by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS). For example, Professor Allan S. Hoffman’s team in the United States [

38] uniformly dispersed silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on the surface of polyurethane vascular stents, significantly inhibiting the growth of

Staphylococcus aureus and

Staphylococcus epidermidis while maintaining excellent biocompatibility. Additionally, Matsumoto et al. [

39] in Japan employed a sol–gel method to load CuO nanoparticles onto polyether ether ketone (PEEK) surfaces. This treatment achieved over 98% inhibition of Escherichia coli within 72 h, with no observed cytotoxicity.

Immobilization of Antimicrobial Peptides (AMP): Antimicrobial peptides are a class of naturally occurring antibacterial molecules composed of cationic amino acids that can penetrate bacterial membranes and cause cell lysis. By covalently grafting antimicrobial peptides (such as LL-37 and magainin II) onto material surfaces, long-lasting antibacterial effects can be achieved with reduced susceptibility to resistance development. For example, Anders Hakansson’s team in Sweden [

40] immobilized the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 onto the surface of polylactic acid (PLA) vascular grafts. They found that this not only effectively inhibited the colonization of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria but also reduced the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 released by macrophages, thereby achieving dual antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects.

Dual-Function Antimicrobial–Anticoagulant Coating: To simultaneously prevent infection and thrombosis, dual-functional surface designs have been proposed in recent years. Professor Guillermo Ameer’s team [

41] in the United States developed an NO (nitric oxide)-releasing antimicrobial coating. By immobilizing nitrate groups on a polyurethane surface, it achieves sustained release of low-concentration NO. This not only inhibits bacterial adhesion but also suppresses platelet activation and adhesion, thereby improving overall blood compatibility.

3.3.2. Anti-Inflammatory Function Introduction Strategy

Immobilized anti-inflammatory molecules: Local inflammatory responses trigger excessive release of cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, leading to vascular endothelial hyperplasia and stent narrowing. Fixing anti-inflammatory molecules or natural polysaccharides to the surface can effectively mitigate this reaction. For example, the research team led by Zhao Yong [

42] at the Chinese Academy of Sciences modified natural polysaccharide chitosan through carboxymethylation and immobilized it on the surface of polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds. Experimental results demonstrated that this approach significantly reduced monocyte adhesion and inflammatory cytokine expression. Meanwhile, Joseph Karp’s team [

43] in the United States employed layer-by-layer (LbL) self-assembly technology to covalently graft interleukin-10 (IL-10) onto polyurethane surfaces. In subsequent subcutaneous implantation experiments in rats, a significant increase in the proportion of M2-polarized macrophages was observed, indicating that this strategy can induce anti-inflammatory and reparative responses.

Sustained-Release System for Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: Local sustained release can be achieved by encapsulating anti-inflammatory drugs (such as dexamethasone and indomethacin) or natural anti-inflammatory molecules (curcumin and resveratrol) within polymer microspheres or coatings. For example, Chen Liqun’s team at Zhejiang University in China [

44] designed a curcumin-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) coated vascular stent that sustained drug release over 14 days, reducing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by over 50% and mitigating acute inflammatory responses.

3.3.3. Integrated Design and Development Trends

Currently, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory functions are often integrated into multilayer composite surfaces to achieve “antimicrobial–anticoagulant–anti-inflammatory” triple protection. For example, the outer layer consists of a silver ion-chitosan composite layer responsible for antimicrobial activity and promoting tissue repair, while the inner layer comprises a heparinized layer or NO-releasing layer to regulate blood compatibility. Future research trends will focus on: Smart responsive antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory systems (e.g., pH- or enzyme-triggered release); Biodegradable antimicrobial nanocarriers (e.g., MOF, PLGA nanoparticles); Multidisciplinary strategies to achieve long-term stable blood contact safety.

4. Release of Active Molecules and Functionalization Design

By introducing bioactive molecules onto the surface of vascular graft materials, artificial blood vessels can be endowed with antithrombotic functions similar to those of the native endothelium. In recent years, researchers have increasingly explored controlled-release strategies to enable the sustained delivery of anticoagulant or thrombolytic agents, thereby achieving long-term suppression of coagulation pathways while simultaneously promoting endothelialization.

4.1. Sustained Release of Anticoagulant Substances

Heparin, as the earliest and most used anticoagulant, has a high negative charge density that binds to antithrombin III to inhibit thrombin activity. Traditional immobilization methods include physical adsorption, ionic bonding, and covalent coupling, but these approaches suffer from issues such as unstable release rates or reduced biological activity [

45]. To this end, Professor Langer’s team [

46] at MIT employed layer-by-layer assembly technology to construct a multilayer heparin/chitosan composite membrane, achieving slow and stable heparin release over a 30-day period to effectively maintain anticoagulation. Meanwhile, Takei et al. [

47] at the University of Tokyo covalently linked heparin to collagen-binding domain fragments, firmly anchoring them to a polyurethane substrate. This approach significantly reduced direct blood-material contact, thereby enhancing anticoagulation durability.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a crucial signaling molecule secreted by endothelial cells that inhibit platelet adhesion and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. To mimic this natural regulatory mechanism, the team led by Liu Xinyong [

48] at the Chinese Academy of Sciences designed a catalytic system based on a dopamine-copper ion composite coating. This enables the material surface to continuously generate NO in situ (release rate: 0.5–4.0 × 10

−10 mol·cm

−2·min

−1) with stable release for more than 30 days. In vivo experiments demonstrated that this material significantly reduces the thrombus formation area while maintaining excellent patency rates.

4.2. Introduction to Thrombolytic and Antiplatelet Mechanisms

In addition to anticoagulation, the introduction of tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) enables localized thrombolysis. Professor Hubbell [

49] at ETH Zurich designed a thrombin-responsive release system based on polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogels: when thrombosis occurs, elevated local thrombin concentrations trigger t-PA release, enabling “on-demand thrombolysis” and reducing systemic bleeding risks. Additionally, conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) is a natural fatty acid with anti-inflammatory and antiplatelet aggregation effects. Kim et al. [

50] from Pusan National University in South Korea grafted CLA onto the surface of polycaprolactone (PCL), enabling it to effectively inhibit the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway and reduce platelet activation levels. More importantly, this modification system not only preserves the material’s mechanical properties but also promotes adhesion and proliferation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), demonstrating dual functions of anticoagulation and endothelialization.

4.3. Smart Controlled-Release and Multi-Component Composite Design

To achieve long-term stable and tunable drug release, researchers have proposed a “smart controlled release” strategy. By loading anticoagulant or anti-inflammatory molecules into nanoparticles, hydrogels, or 3D-printed multilayer structures, responsive release can be achieved in response to environmental signals such as pH, enzyme concentration, or shear stress [

51]. For example, Zhang Qiang’s team at Tsinghua University [

52] developed a shear-stress-responsive hydrogel system containing the NO precursor molecule S-nitrosothiol (RSNO). Under high blood flow shear stress, the hydrogel pores dynamically open to promote NO release; when blood flow slows, the release rate automatically decreases, achieving anticoagulant regulation that matches physiological conditions.

Meanwhile, the Grayson team [

53] at Duke University in the United States layered multiple anticoagulant drugs (heparin, aspirin, NO precursors) onto a 3D-printed porous polylactic acid scaffold, forming a multicomponent composite system. In vitro simulated circulation experiments demonstrated that this structure could release active components layer by layer in response to shear stress, maintaining anticoagulant activity for over 60 days while promoting vascular endothelialization and reconstruction. These studies, based on smart materials and multicomponent composite design, mark a shift in artificial blood vessels from “passive antithrombotic” to “adaptive hemocompatibility,” laying a crucial foundation for the long-term clinical application of next-generation artificial blood vessels.

5. Cell and Tissue Engineering Strategies

In the research and application of small-caliber artificial blood vessels, material properties are undoubtedly crucial. However, relying solely on inert or biodegradable materials is insufficient to sustain graft function over the long term. Extensive evidence indicates that inadequate endothelialization, thrombosis, and intimal hyperplasia are the primary causes of premature failure in small-diameter artificial vessels [

54] (

Figure 5). Consequently, cellular and tissue engineering strategies are considered pivotal for advancing artificial vessels toward “activation.” The core objective is to leverage cells and bioactive factors to participate in vascular regeneration and remodeling, gradually transforming the graft into a physiologically functional “regenerative vessel” [

54,

55] (

Figure 5).

First, the selection of seed cells lays the foundation for the construction of tissue-engineered artificial blood vessels. Endothelial cells (ECs) have been extensively studied due to their critical roles in vascular endothelialization and anti-thrombotic functions [

56]. Early research primarily relied on ECs isolated from autologous vessels, but this approach faced clinical limitations due to donor scarcity and difficulties in acquisition. Subsequently, peripheral blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and stem cell-induced differentiated ECs emerged as alternative options [

57]. Beyond ECs, smooth muscle cells (SMCs) play a vital role in forming the vascular media and regulating vasoconstriction. Seeding SMCs facilitates the gradual establishment of a media structure resembling natural blood vessels on scaffolds, enhancing long-term mechanical stability [

58]. Concurrently, stem cells such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have garnered significant attention due to their relatively abundant sources and strong expansion potential. Through directed induction, these cells can differentiate into ECs or SMCs, offering new possibilities for artificial vascular regeneration [

59].

In terms of cell seeding and culture methods, research has evolved from static seeding to dynamic culture. While traditional static seeding methods are operationally simple, they exhibit low cell adhesion efficiency and uneven distribution. With advancements in bioreactor technology, perfusion or rotary dynamic culture systems have gained widespread adoption [

60]. These systems not only significantly enhance cell seeding efficiency and uniformity but also mimic the in vivo blood flow shear stress. This induces endothelial cells to form functional monolayers and maintain physiological phenotypes. Furthermore, the emerging “in situ tissue engineering” strategy aims to bypass the complexity of ex vivo cell manipulation. By designing materials and loading bioactive factors, it directly attracts host cells into scaffolds to complete vascular regeneration and reconstruction. This approach holds promises for reducing clinical costs and regulatory barriers, making it a key focus of current research [

61].

The regulation of bioactive molecules and signaling factors is equally critical in tissue-engineered artificial blood vessels. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) significantly promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration, accelerating the formation of the endothelial layer; basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) supports the co-growth of endothelial and smooth muscle cells [

62]. Nitric oxide (NO), as a vasodilator, effectively inhibits platelet adhesion and aggregation, while transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) participates in extracellular matrix deposition and long-term vascular wall remodeling. By rationally designing sustained-release systems for these factors, researchers can modulate the vascular regeneration process at different time points, ensuring early endothelialization while also facilitating the maturation of vascular wall structure in later stages [

63].

Animal studies have further elucidated the regenerative mechanisms of tissue-engineered artificial blood vessels. In large animal models such as rabbits, pigs, and dogs, seeding cells onto scaffolds often significantly improve short-term patency rates, with endothelialization and the formation of a new intima observed within weeks to months [

64]. The fundamental mechanism can be summarized as follows: exogenous cells initially serve as “placeholders” and provide functional support, gradually being replaced by host-derived cells. During this process, the scaffold degrades and is filled with newly generated extracellular matrix and host tissue, ultimately forming a structure resembling natural blood vessels. However, the success of this process depends heavily on matching the scaffold degradation rate to the tissue regeneration rate. If degradation occurs too rapidly, it may lead to insufficient mechanical support and premature failure; if degradation is too slow, it may hinder complete integration with host tissue [

65].

Overall, cell and tissue engineering strategies offer novel approaches to functionalizing small-caliber artificial blood vessels and ensuring their long-term patency. Research is shifting from reliance on exogenous cells toward endogenous regeneration driven by material-host interactions, evolving from multi-step synergistic processes like “seed cell seeding—biofactor regulation—host tissue reconstruction” to the emerging concept of “in vivo regeneration.” Nevertheless, several challenges persist in this field, including the availability and clinical feasibility of seed cells, the complexity and cost of in vitro culture systems, and regulatory hurdles for cell- and factor-based products. Future trends may involve integrating exogenous cell mechanisms with host cell regeneration—promoting early functional establishment through limited cell pretreatment, followed by long-term remodeling relying on the host’s regenerative potential [

66] (

Figure 6).

6. Strategies for Gene and Molecular Level Regulation of Small-Caliber Artificial Blood Vessels

With the rapid convergence of biomaterials science and molecular biology technologies, researchers have increasingly recognized that relying solely on physical or chemical surface modifications cannot fundamentally inhibit thrombosis [

67]. The key to maintaining blood flow in natural blood vessels lies in the diverse signaling molecules secreted by endothelial cells, such as nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin (PGI

2), and various anticoagulant proteins. These molecules form a complex endogenous anticoagulant network. Therefore, reconstructing this “physiological anticoagulation mechanism” has become a new focus in research on small-diameter artificial blood vessels. In recent years, scholars worldwide have been advancing the transformation of artificial blood vessels from “inert materials” to “active protection systems” through strategies such as genetic engineering, targeted peptide modification, and signaling pathway regulation [

68].

6.1. Genetic Engineering Promotes Endothelialization and Restoration of Anticoagulant Function

Genetic engineering technology can introduce specific genes into endothelial cells or seed cells via viral or non-viral vectors, enabling them to continuously secrete anticoagulant factors in vivo and mimic the biological functions of natural blood vessels.

6.1.1. VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) Gene Delivery

The Langer team [

69,

70] at MIT encapsulated the VEGF165 gene within cationic liposomes and implanted the liposomes into polylactic acid scaffolds, achieving sustained local release. Animal studies demonstrated continuous endothelial layer formation on the inner surface of the artificial vessel within 10 days post-implantation, with platelet adhesion rates reduced by approximately 70%. Similarly, Li Ge’s team at Tsinghua University [

71] encapsulated VEGF within PLGA nanoparticles and employed electrospinning technology to construct a “local sustained-release system,” further validating this strategy’s highly efficient endothelialization effects in a rabbit carotid artery model.

6.1.2. eNOS (Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase) Gene Transfection

K. Sato et al. from the University of Tokyo [

67] used an adenovirus vector to transfect endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) with the eNOS gene, which were then seeded onto the inner walls of degradable artificial blood vessels, achieving stable in vivo NO release. Results demonstrated that this strategy increased the 4-week patency rate of grafts by approximately 40% in a rat carotid artery model and effectively suppressed smooth muscle cell proliferation.

6.1.3. Co-Expression of t-PA and Hep-III Genes

The team led by B. Haverich [

72] at RWTH Aachen University constructed a composite vector system that simultaneously expressed the t-PA and Hep-III fragment genes, achieving a synergistic balance between anticoagulation and thrombolysis. Experiments revealed that this composite gene-modified scaffold significantly prolonged thrombus-free survival in a canine femoral artery model. These studies demonstrate that genetic modification can confer long-term, active antithrombotic properties to artificial blood vessels. However, viral vector safety, immunogenicity, and sustained gene expression remain current technical bottlenecks. In recent years, non-viral nanocarriers and degradable polymer delivery systems have emerged as new research directions, exhibiting superior biosafety and controllability [

73,

74].

6.2. Targeted Peptide Sequences and Molecular Recognition Mechanisms

Beyond the genetic level, molecular recognition via specific peptide sequences also provides an effective means to achieve “selective endothelialization”.

6.2.1. Cell Adhesion Peptides (RGD, REDV, YIGSR)

Short peptides such as RGD (Arginine–Glycine–Aspartic acid), REDV (Arginine–Glutamic acid–Aspartic acid–Valine), and YIGSR (Tyrosine–Isoleucine–Glycine–Serine–Arginine) can specifically bind to integrin receptors (e.g., αvβ3 and α5β1), thereby promoting endothelial cell adhesion and migration. Professor Hubbell’s team [

75] at ETH Zurich in Switzerland was the first to report research on REDV-modified polyurethane scaffolds. Results demonstrated higher selectivity toward endothelial cells, reducing platelet adhesion by approximately 60%. Meanwhile, RGD peptides offer broad compatibility but carry the risk of non-specific binding. Spatial configuration optimization is required to enhance selectivity, for example, through regulation of intermolecular spacing or steric hindrance.

6.2.2. Peptide Functional Composite System

The team led by J. Chaikof [

75] at Stanford University developed a multilayer composite system featuring covalently immobilized QK peptides (VEGF mimetic peptides). By layer-by-layer self-assembly of RGD/YIGSR composite peptide layers, they achieved direct endothelial cell spreading. By further integrating a molecular co-design strategy with a NO release system, they demonstrated 100% graft patency within 30 days post-surgery in animal experiments.

6.3. Signal Pathway Regulation and Molecular Mechanisms

The essence of blood compatibility lies in the dynamic equilibrium between cells and signaling molecules. Research indicates that the integrin–FAK pathway, the NO–cGMP pathway, and the PI3K/Akt signaling axis are the three core pathways that determine endothelial function and antithrombotic properties. Integrin–FAK pathway: Peptide-modified materials activate integrin receptors, promoting endothelial cytoskeletal reorganization and spreading. Liu Tong’s group at Shanghai Jiao Tong University [

65] validated the critical role of this pathway in rapid endothelialization of artificial vessels through FAK inhibition experiments. NO–cGMP pathway: Nitric oxide activates soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), elevating cGMP levels to inhibit platelet activation. Long-term pathway activity can be maintained through NO donor release or eNOS upregulation. PI3K/Akt signaling axis: This pathway regulates endothelial cell survival and anti-apoptotic functions. VEGF and bFGF activate eNOS expression via Akt phosphorylation, forming a positive feedback loop of “endothelialization-promoting and anti-thrombotic” effects. By precisely regulating these signaling networks, artificial blood vessels can reconstruct endogenous anticoagulation mechanisms at the molecular level, achieving a transition from “passive inertia” to “active physiological protection.”

6.4. Multi-Level Coordination and Integrated Strategy

Current research trends are shifting from single strategies toward multidimensional integration. Through multi-layered synergistic design combining “material modification + active molecule release + genetic modification + cell engineering,” the performance of artificial blood vessels can be comprehensively enhanced. For instance, Wang Liping’s team at Zhejiang University [

51] immobilized RGD peptides on electrospun scaffolds and sustained-released VEGF, significantly accelerating endothelialization rates; Meanwhile, H. Ishibashi’s team [

76] at Osaka University combined eNOS gene transfection with a NO-releasing microcapsule system to construct a self-regulating antithrombotic system capable of sustaining long-term NO levels. Further integration with 3D printing or nanofiber hierarchical structures enables multifunctional integrations such as anticoagulation, antibacterial properties, and self-repair—within a single scaffold.

This multi-level bionic approach signifies that research on Tissue-Engineered Vascular Graft (TEVG) is advancing toward the development of “physiologically functional regenerative vessels.” Such vessels not only provide mechanical support but also actively participate in regulating the body’s vascular homeostasis.

7. Future Development Directions and Outlook

Research and application of small-caliber artificial blood vessels have spanned decades. Although ideal clinical replacement has yet to be fully achieved, advancements in materials science, tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and manufacturing technologies are progressively driving their maturation. Future development directions can be anticipated in the following areas:

First, the intelligence and functionalization of materials will emerge as a significant trend. Single-component inert synthetic materials struggle to meet clinical demands, necessitating future research focused on developing biomimetic and smart, responsive materials. These materials can adaptively adjust their surface properties in response to local hemodynamics or microenvironmental changes, thereby dynamically maintaining hemocompatibility and tissue integration.

Secondly, rapid and stable endothelialization is crucial for enhancing the long-term patency rate of small-diameter artificial blood vessels. The formation mechanism, structural characteristics, and impact on blood compatibility of plasma protein adsorption layer are the theoretical basis for understanding the biological reactions of blood contact materials [

76]. Focusing on the biocompatibility and modification strategies of interventional catheter surfaces, emphasizing protein adsorption, cell adhesion, and vascular endothelial response [

77]. In terms of materials, we focus on adhesive hydrogels prepared from natural polymers (such as gelatin, chitosan, alginate, etc.) and their applications in hemostasis, tissue adhesion, etc. [

78] (

Figure 7). Smart responsive hydrogels are also widely used in wearable bioelectronic devices [

79], including drug delivery, tissue engineering and sensors [

80]. Future approaches may increasingly rely on controlled-release systems for bioactive molecules, stem cell-derived functional cells, and surface micro/nano-structural modifications to promote endothelial cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration, thereby shortening the time required for endothelialization [

81].

Thirdly, the application of advanced manufacturing technologies will offer new solutions for small-caliber artificial blood vessels. Techniques such as 3D bioprinting, coaxial electrospinning, and microfluidic fabrication enable precise control at both macro and micro levels, thereby enabling the construction of hierarchical, personalized bionic vascular structures. The future development of personalized medicine may propel “on-demand customized” artificial blood vessels into clinical practice [

80].

Fourthly, multidisciplinary integration and clinical translation will serve as the core drivers that propel artificial blood vessel research toward practical applications. The development of small-diameter artificial blood vessels requires not only collaboration between materials science and biomedical engineering but also the involvement of surgical clinicians to ensure laboratory outcomes are genuinely adaptable to clinical settings. Simultaneously, achieving scalable, standardized production while meeting GMP and international regulatory requirements presents an unavoidable challenge for the future.

Finally, long-term follow-up and large-scale clinical trials are crucial for validating the efficacy and safety of small-diameter artificial blood vessels. Although some products have entered clinical trials, the limited sample size and short follow-up periods make it difficult to comprehensively evaluate long-term outcomes. Future efforts should establish a multicenter, large-sample clinical research system to lay a solid foundation for the widespread adoption of artificial blood vessels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and Z.L.; methodology, Z.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.Z., M.Z. and X.J.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, J.J.; resources, Q.W.; data curation, Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z. and Z.L.; writing—review and editing, C.L. and L.Z.; visualization, C.L.; supervision, L.Z.; project administration, Z.Z.; funding acquisition, Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Zhejiang Province Pharmaceutical Regulatory Science and Technology Project (2024019). National Natural Science Foundation of China (52205186).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Seifu, D.G.; Purnama, A.; Mequanint, K.; Mantovani, D. Small-diameter vascular tissue engineering. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.C.; Collins, A.; Ferrari, R.; Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Logstrup, S.; McGhie, D.V.; Ralston, J.; Sacco, R.L.; Stam, H.; Taubert, K. Our time: A call to save preventable death from cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 7, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Chen, S.Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, S.F. Research status and prospects of small-diameter artificial blood vessels construction. Chin. J. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 35, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goins, A.; Webb, A.R.; Allen, J.B. Multi-layer approaches to scaffold-based small diameter vessel engineering: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 97, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.B.; Zhang, X.D. Vascular restoration therapy and bioresorbable vascular scaffold. Regen. Biomater. 2014, 1, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Memic, A.; Annabi, N.; Hossain, M.; Paul, A.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Dehghani, F.; Khademhosseini, A. Electrospun scaffolds for tissue engineering of vascular grafts. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklason, L.E.; Lawson, J.H. Bioengineered human blood vessels. Science 2020, 370, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, G.W.; Poot, A.A.; Beugeling, T.; Van Aken, W.G.; Feijen, J. Small-diameter vascular graft prostheses: Current status. Arch. Int. Physiol. 1998, 106, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mithieux, S.M.; Weiss, A.S. Fabrication techniques for vascular and vascularized tissue engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1900742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ding, B.; Li, B. Biomimetic electrospun nanofibrous structures for tissue engineering. Mater. Today 2013, 16, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorna, K.; Gogolewski, S. Biodegradable porous polyurethane scaffolds for tissue repair and regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 79, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quint, C.; Kondo, Y.; Niklason, L.E.; Lawson, J.H.; Dardik, A. Decellularized tissue-engineered blood vessel as an arterial conduit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9214–9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilla, P.; Bezuidenhout, D.; Human, P. Prosthetic vascular grafts: Wrong models, wrong questions and no healing. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 5009–5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; Turng, L.S. Artificial small-diameter blood vessels: Materials, fabrication, surface modification, mechanical properties, and bioactive functionalities. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 1801–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcraft, M.; Douglass, M.; Chen, Y.J.; Handa, H. Combination strategies for antithrombotic biomaterials: An emerging trend towards hemocompatibility. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 2413–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, C.L.; Cheng, M.J.; Huang, J.; Liu, Q.; Yuan, G.; Lin, K.; Yu, H. Challenges and strategies for in situ endothelialization and long-term lumen patency of vascular grafts. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 1791–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.H.; Kang, D.; An, S.; Ryu, J.Y.; Lee, K.; Kim, J.S.; Song, M.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Kwon, S.M.; Jung, W.K.; et al. Advances in the development of tubular structures using extrusion-based 3D cell-printing technology for vascular tissue regenerative applications. Biomater. Res. 2022, 26, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.F.; Dai, W.W.; Qian, D.H.; Qin, Z.X.; Lei, Y.; Hou, X.Y.; Wen, C. A simply prepared small-diameter artificial blood vessel that promotes in situ endothelialization. Acta Biomater. 2017, 54, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, M.; Kamohara, K.; Node, K.; Nakayama, K. Artificial Blood Vessels–Clinical Development of TEVG. J. Artif. Organs 2025, 28, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.X.; Mo, H.L.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lu, H.J.; Joung, Y.K. Challenges and advances in materials and fabrication technologies of small-diameter vascular grafts. Biomater. Res. 2023, 27, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Li, Y.; Ke, Z.; Yang, H.; Lu, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, W. History, Progress and Future Challenges of Artificial Blood Vessels: A Narrative Review. Biomater. Transl. 2022, 3, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adipurnama, I.; Yang, M.C.; Ciach, T.; Butruk-Raszeja, B. Surface Modification and Endothelialization of Polyurethane for Vascular Tissue Engineering Applications: A Review. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 5, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engbers, G.H.; Feijen, J. Current Techniques to Improve the Blood Compatibility of Biomaterial Surfaces. Int. J. Artif. Organs 1991, 14, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrievska, S.; Maire, M.; Diaz-Quijada, G.A.; Robitaille, L.; Ajji, A.; Yahia, L.H.; Moreno, M.; Merhi, Y.; Bureau, M.N. Low Thrombogenicity Coating of Nonwoven PET Fiber Structures for Vascular Grafts. Macromol. Biosci. 2011, 11, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.B.; Li, W.P.; Chen, Y.; Ye, Y.; Jin, S. Construction of a Fluorescent H2O2 Biosensor with Chitosan 6-OH Immobilized β-Cyclodextrin Derivatives. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellaturay, P.; Nasser, S.; Ewan, P. Polyethylene Glycol-Induced Systemic Allergic Reactions (Anaphylaxis). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Kumar, D.S.; Yoshida, Y.; Jayakrishnan, A. Chemical Modification of Poly(vinyl Chloride) Resin Using Poly(ethylene Glycol) to Improve Blood Compatibility. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3495–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.N.; Tran, N.M.; Phan, T.B.; Tran, P.A.; Dai Tran, L.; Nguyen, T.H. Poloxamer Additive as Luminal Surface Modification to Modulate Wettability and Bioactivities of Small-Diameter Polyurethane/Polycaprolactone Electrospun Hollow Tube for Vascular Prosthesis Applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhanimala, S.K.; Vllasaliu, D.; Raimi-Abraham, B.T. Engineering Biomimetic Gelatin-Based Nanostructures as Synthetic Substrates for Cell Culture. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; Tallawi, M.; Grigore, A.; Boccaccini, A.R. Synthesis, Properties and Biomedical Applications of Poly(glycerol Sebacate) (PGS): A Review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1051–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Savargaonkar, A.V.; Tahir, M.; Sionkowska, A.; Popat, K.C. Surface Modification Strategies for Improved Hemocompatibility of Polymeric Materials: A Comprehensive Review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 7440–7458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, S. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery of a Developing Nation. Indian J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1985, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchinka, J.; Willems, C.; Telyshev, D.V.; Groth, T. Control of Blood Coagulation by Hemocompatible Material Surfaces—A Review. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Gao, C.; He, T.; Shen, J. Layer-by-Layer Assembly to Modify Poly(L-lactic Acid) Surface toward Improving Its Cytocompatibility to Human Endothelial Cells. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Han, D.; Jiang, L. On Improving Blood Compatibility: From Bioinspired to Synthetic Design and Fabrication of Biointerfacial Topography at Micro/Nano Scales. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 85, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriere, G.; Fici, P.; Gallerani, G.; Fabbri, F.; Rigaud, M. Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition: A Double-Edged Sword. Clin. Transl. Med. 2015, 4, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Jian, Z.; Lu, C.; Liu, N.; Yue, T.; Lan, W.; Liu, Y. New Method for Preparing Small-Caliber Artificial Blood Vessel with Controllable Microstructure on the Inner Wall Based on Additive Material Composite Molding. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, A.V.; Ritz, S.; Pütz, S.; Mailänder, V.; Landfester, K.; Ziener, U. Bioinspired Phosphorylcholine-Containing Polymer Films with Silver Nanoparticles Combining Antifouling and Antibacterial Properties. Biomater. Sci. 2013, 1, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.M.; Cheng, L.; Liu, Z.T.; Zhao, J.J. Surface Characteristics of Zinc–TiO2 Coatings Prepared via Micro-Arc Oxidation. Compos. Interfaces 2014, 21, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Carvalho, I.F.; Montelaro, R.C.; Gomes, P.; Martins, M.C.L. Covalent Immobilization of Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) onto Biomaterial Surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wang, L.; Dou, L.; Shang, Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, J.; Yuan, J. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Porous Coating with Antibacterial Activity and Blood Compatibility. Langmuir 2024, 2, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, E.; Ibanez, H.; del Valle, L.J.; Puiggalí, J. Biocompatibility and Drug Release Behavior of Scaffolds Prepared by Coaxial Electrospinning of Poly(butylene Succinate) and Polyethylene Glycol. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 49, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, E.C.; Jarnicki, A.; McNeela, E.; Armstrong, M.E.; Higgins, S.C.; Leavy, O.; Mills, K.H. Effects of Cholera Toxin on Innate and Adaptive Immunity and Its Application as an Immunomodulatory Agent. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004, 75, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Lee, J.D.; Park, C.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, G.Y. Curcumin Attenuates the Release of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated BV2 Microglia. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007, 28, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björk, I.; Lindahl, U. Mechanism of the Anticoagulant Action of Heparin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1982, 48, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Liu, Z.; Shen, L.; Guo, Z.; Chou, L.L.; Zhong, W.; Du, Q.; Ge, J. The Effect of a Layer-by-Layer Chitosan–Heparin Coating on the Endothelialization and Coagulation Properties of a Coronary Stent System. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2276–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.-S.; Seo, E.J.; Kang, I.K. Synthesis and Characterization of Heparinized Polyurethanes Using Plasma Glow Discharge. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yu, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xu, S.; Zhang, H.; Shen, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, K.; et al. Hydrodynamic-Derived Centrifugal Blood Pump Design for Stable Low-Flow-Rate Performance: From Surface to Structure. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 54, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, J.J.; Tsirka, S.E. Fibrin-Modifying Serine Proteases Thrombin, tPA, and Plasmin in Ischemic Stroke: A Review. Glia 2005, 50, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, H.; Gimbrone, M.A.; Schafer, A.I. Vascular Lipoxygenase Activity: Synthesis of 15-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid from Arachidonic Acid by Blood Vessels and Cultured Vascular Endothelial Cells. Thromb. Res. 1987, 45, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P.H.; Engberg, A.E.; Bäck, J.; Faxälv, L.; Lindahl, T.L.; Nilsson, B.; Ekdahl, K.N. The Creation of an Antithrombotic Surface by Apyrase Immobilization. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4484–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiordeliso, J.; Bron, S.; Kohn, J. Design, Synthesis, and Preliminary Characterization of Tyrosine-Containing Polyarylates: New Biomaterials for Medical Applications. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 1994, 5, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroni, A.; Melocchi, A.; Parietti, F.; Foppoli, A.; Zema, L.; Gazzaniga, A. 3D Printed Multi-Compartment Capsular Devices for Two-Pulse Oral Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 2017, 268, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdrahala, R.J. Small Caliber Vascular Grafts. Part I: State of the Art. J. Biomater. Appl. 1996, 10, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.D.; Sawh-Martinez, R.; Brennan, M.P.; Jay, S.M.; Devine, L.; Rao, D.A.; Yi, T.; Mirensky, T.L.; Nalbandian, A.; Udelsman, B.; et al. Tissue-Engineered Vascular Grafts Transform into Mature Blood Vessels via an Inflammation-Mediated Process of Vascular Remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4669–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Chang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Lei, W.X.; Li, B.C.; Ren, K.F.; Ji, J. Mechanical Adaptability of the MMP-Responsive Film Improves the Functionality of Endothelial Cell Monolayer. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1601410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koobatian, M.T.; Row, S.; Smith, R.J.; Koenigsknecht, C.; Andreadis, S.T.; Swartz, D.D. Successful Endothelialization and Remodeling of a Cell-Free Small-Diameter Arterial Graft in a Large Animal Model. Biomaterials 2016, 76, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibino, N.; Villalona, G.; Pietris, N.; Duncan, D.R.; Schoffner, A.; Roh, J.D.; Yi, T.; Dobrucki, L.W.; Mejias, D.; Sawh-Martinez, R. Tissue-Engineered Vascular Grafts Form Neovessels That Arise from Regeneration of the Adjacent Blood Vessel. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teebken, O.E.; Haverich, A. Tissue Engineering of Small Diameter Vascular Grafts. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2002, 23, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Ma, T. Perfusion Bioreactor System for Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Tissue Engineering: Dynamic Cell Seeding and Construct Development. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005, 91, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutzweiler, G.; Ndreu Halili, A.; Engin Vrana, N. The Overview of Porous, Bioactive Scaffolds as Instructive Biomaterials for Tissue Regeneration and Their Clinical Translation. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syedain, Z.; Reimer, J.; Lahti, M.; Berry, J.; Johnson, S.; Bianco, R.; Tranquillo, R.T. Tissue Engineering of Acellular Vascular Grafts Capable of Somatic Growth in Young Lambs. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, J.C.; Banga, J.D.; Moncada, S.; Palmer, R.M.; de Groot, P.G.; Sixma, J.J. Nitric Oxide Functions as an Inhibitor of Platelet Adhesion under Flow Conditions. Circulation 1992, 85, 2284–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Z.; Chen, T.; Zhu, S.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y.; Miao, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, R.X. Construction of Vascular Grafts Based on Tissue-Engineered Scaffolds. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 29, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.; King, M.W. Design Concepts and Strategies for Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2011, 58, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radke, D.; Jia, W.; Sharma, D.; Fena, K.; Wang, G.; Goldman, J.; Zhao, F. Tissue Engineering at the Blood-Contacting Surface: A Review of Challenges and Strategies in Vascular Graft Development. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1701461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, S.P.; Stainier, D.Y.R. Molecular Control of Endothelial Cell Behaviour during Blood Vessel Morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.; Malik, A.B. Signaling Mechanisms Regulating Endothelial Permeability. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86, 279–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lash, L.H. Mitochondrial Glutathione Transport: Physiological, Pathological and Toxicological Implications. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2006, 163, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peppas, N.A.; Hilt, J.Z.; Khademhosseini, A.; Langer, R. Hydrogels in Biology and Medicine: From Molecular Principles to Bionanotechnology. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.P.; Hunter, T.J.; Falkow, L.J.; Evancho, M.M.; Sharp, W.V. Effects of antiplatelet agents in combination with endothelial cell seeding on small-diameter Dacron vascular graft performance in the canine carotid artery model. J. Vasc. Surg. 1985, 2, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M.; Meinhart, J.; Fischlein, T.; Preiss, P.; Zilla, P. Clinical autologous in vitro endothelialization of infrainguinal ePTFE grafts in 100 patients: A 9-year experience. Surgery 1999, 126, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tao, J.; Wang, J.M.; Tu, C.; Xu, M.G.; Wang, Y.; Pan, S.R. Shear stress contributes to t-PA mRNA expression in human endothelial progenitor cells and nonthrombogenic potential of small diameter artificial vessels. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 342, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Hu, M.; Jing, D. The Synergistic Effect Between Surfactant and Nanoparticle on the Viscosity of Water-Based Fluids. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 727, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, N. The structure, formation, and effect of plasma protein layer on the blood contact materials: A review. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2022, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Wisniewski, S.; Lee, E.S.; Winn, M.L. Role of protein and fatty acid adsorption on platelet adhesion and aggregation at the polymer interface. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1977, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Lin, C.; Wang, C. Research Progress of the Interaction Between Blood Vessels and Intervention Catheters and Its Surface Modification. Friction 2025, 7, 9441003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Xie, C.; Lu, X. Natural Polymer-Based Adhesive Hydrogel for Biomedical Applications. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2022, 8, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Xu, J.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, L. Recent Progress on Smart Hydrogels for Biomedicine and Bioelectronics. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2022, 8, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, X.; Han, L. Recent Developments in Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2022, 8, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.V.; Atala, A. 3D Bioprinting of Tissues and Organs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).