Effect of Nb Contents on Microstructure and Tribological Properties of FeCoCrNiNbxN Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Film Fabrication

2.2. Characterization of Film Properties

3. Results and Discuss

3.1. Phase Composition

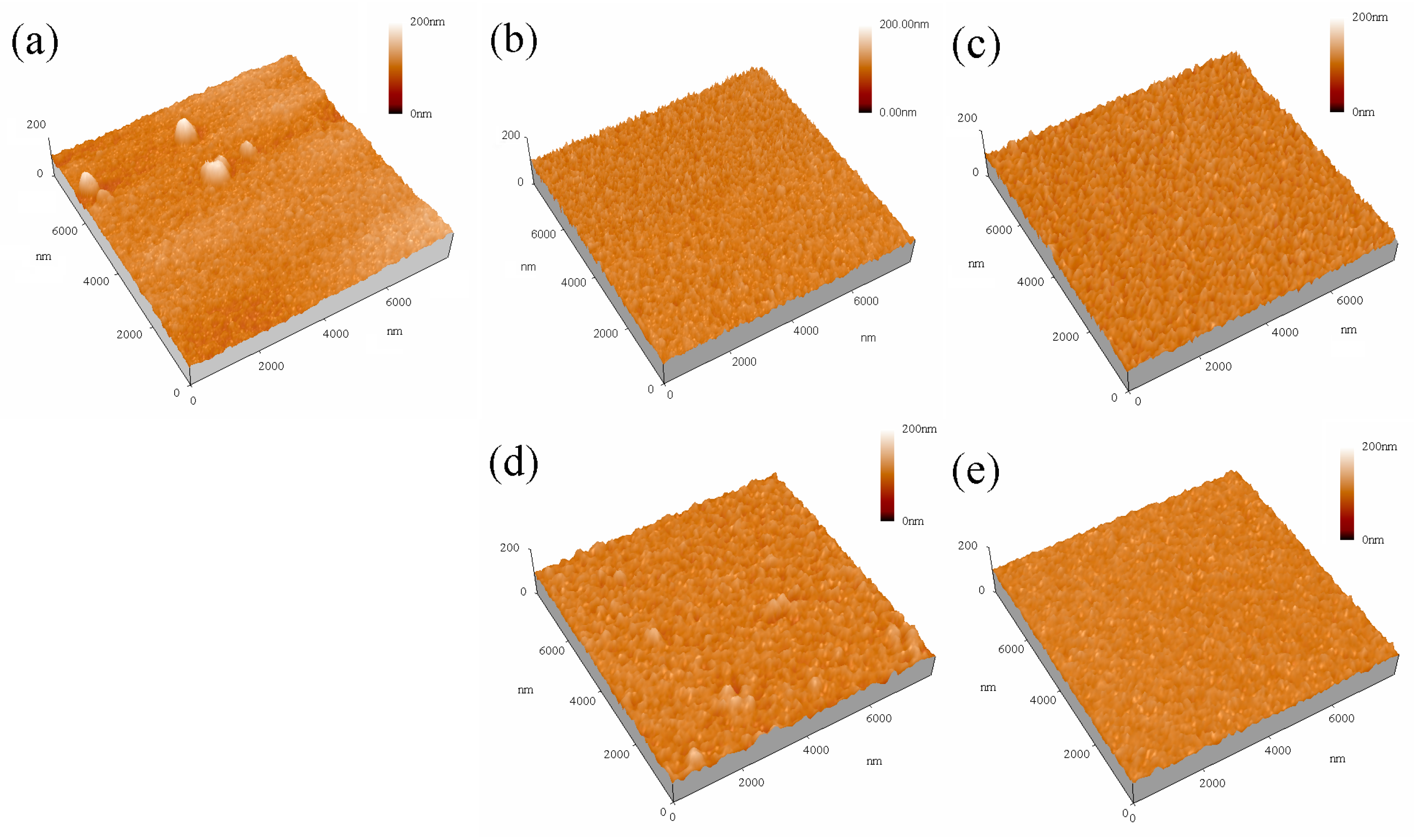

3.2. Cross-Sectional and Surface Morphologies

3.3. Mechanical Properties

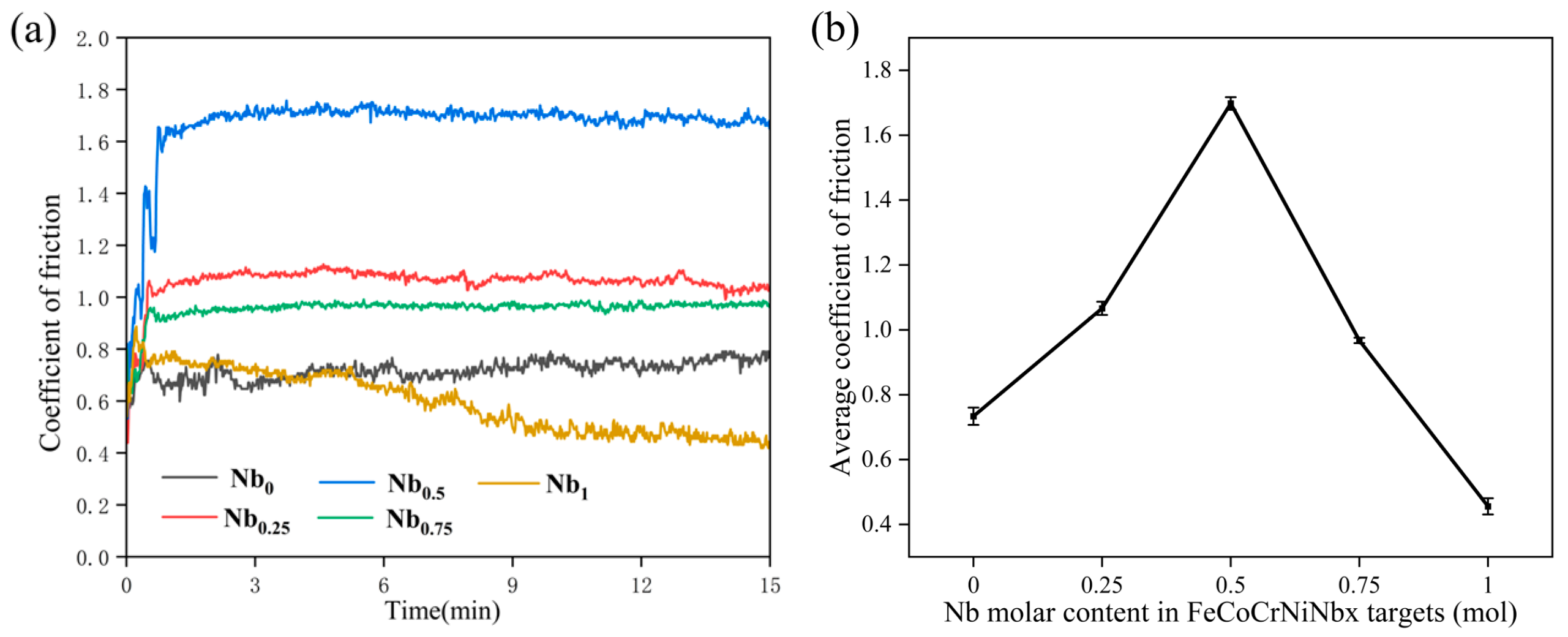

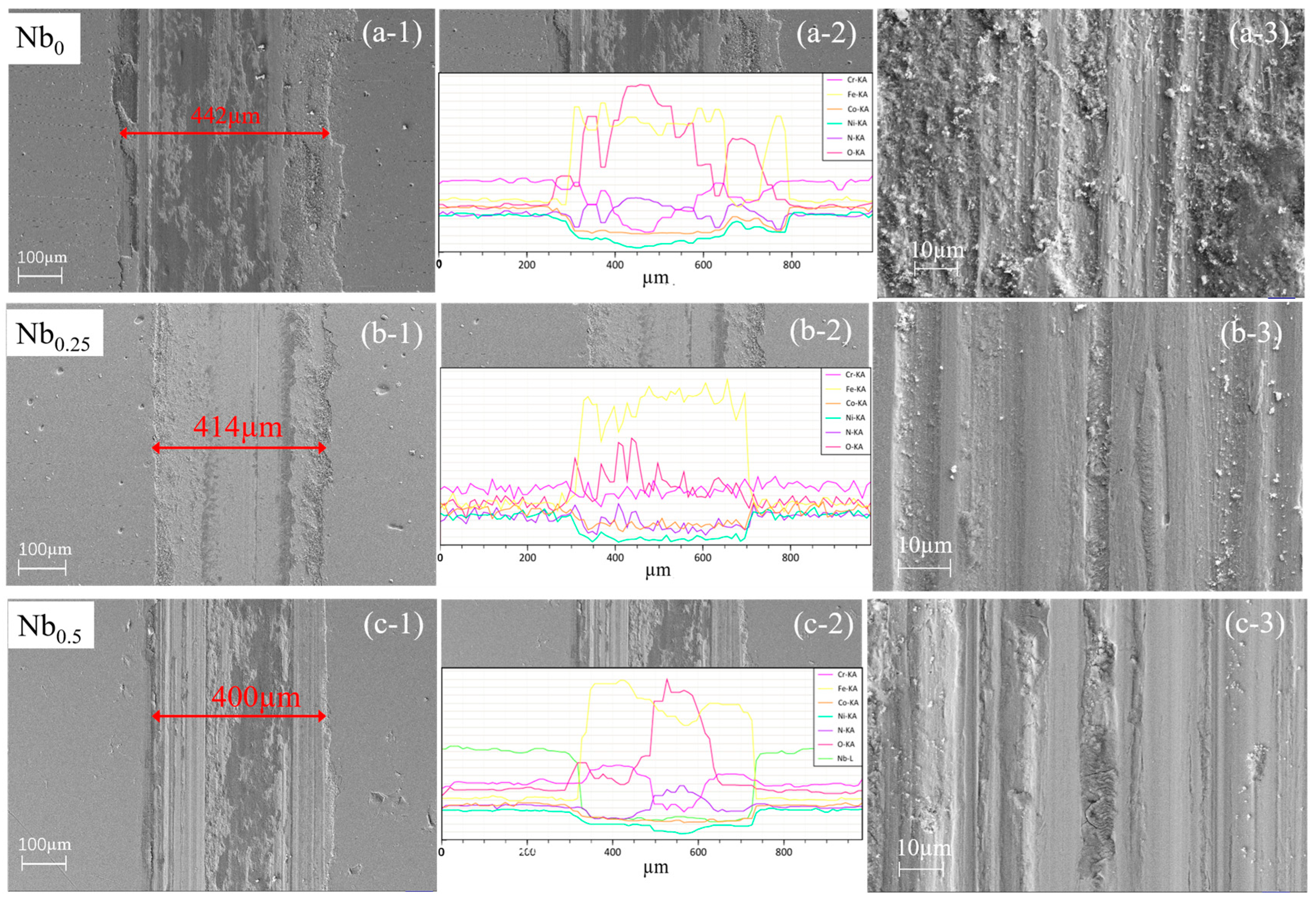

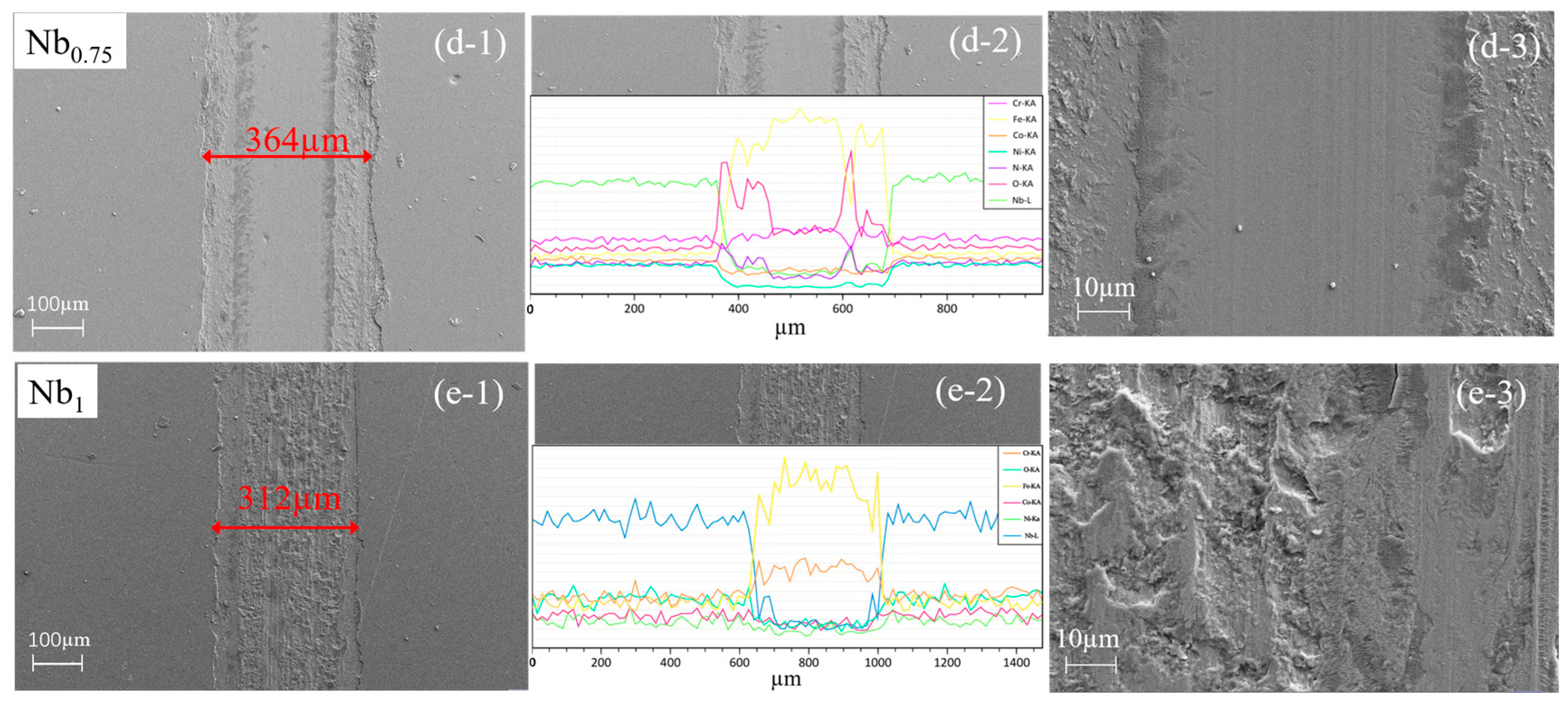

3.4. Tribological Properties

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The FeCoCrNiNbxN films exhibit an FCC structure with a preferred orientation in the (200) planes. With an increasing Nb content, the preferred orientation plane changes from the (200) plane to the (111) plane and the interplanar distance firstly increases and then decreases in the (200) plane.

- (2)

- With an increasing Nb content, the hardness and elastic modulus of the films firstly decline and then raise. The Nb1 film exhibits the maximum hardness of (25.56 ± 0.95) GPa and elastic modulus of (265.36 ± 2.64) GPa. Typical high-entropy effects such as lattice distortion and solution strengthening contribute to improving the mechanical properties.

- (3)

- With an increasing Nb content, the friction coefficient, wear volume, and wear rate decrease significantly, with the Nb1 film showing the lowest values. The wear mechanisms are abrasive wear and oxidation wear. The increasing NbN phase, crystal densification, the smallest average surface roughness and highest H3/E2 help to improve the tribological properties.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ciulli, E. Vastness of Tribology Research Fields and Their Contribution to Sustainable Development. Lubricants 2024, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S. Advances in Tribology of Aero-Engine Materials. Tribology 2023, 43, 1099–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X. Research Progress of High-Speed Wheel–Rail Relationship. Lubricants 2022, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural Development in Equiatomic Multicomponent Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrami, S.; Edalati, P.; Fuji, M.; Edalati, K. High-entropy ceramics: Review of principles, production and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2021, 146, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xie, D.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liaw, P.K. Mechanical behavior of high-entropy alloys: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 118, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolar, S.; Ito, Y.; Fujita, T. Future prospects of high-entropy alloys as next-generation industrial electrode materials. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 8664–8722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, D. Synthesis and Characterization of Super-Hard AlCrTiVZr High-Entropy Alloy Nitride Films Deposited by HiPIMS. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 394, 125836. [Google Scholar]

- Pshyk, A.V.; Vasylenko, A.; Bakhit, B.; Hultman, L.; Schweizer, P.; Edwards, T.E.J.; Michler, J.; Greczynski, G. High-Entropy Transition Metal Nitride Thin Films Alloyed with Al: Microstructure, Phase Composition and Mechanical Properties. Mater. Des. 2022, 219, 110798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, F.; Chen, G.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z. Super-Hard (MoSiTiVZr)Nx High-Entropy Nitride Coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 926, 166807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Yang, Y. Microstructure and Properties of CoCrFeNiMnTix High-Entropy Alloy Coated by Laser Cladding. Coatings 2024, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Guan, K.; Bao, Y.; Mao, Z.; Wang, F.; Dai, H. Effect of Nb Addition on the Corrosion and Wear Resistance of Laser Clad AlCr2FeCoNi High-Entropy Alloy Coatings. Lubricants 2024, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, R.; Lundin, D.; Xin, B.; Sortica, M.A.; Primetzhofer, D.; Magnuson, M.; Le Febvrier, A.; Eklund, P. Influence of Metal Substitution and Ion Energy on Microstructure Evolution of High-Entropy Nitride (TiZrTaMe)N1−x (Me = Hf, Nb, Mo, or Cr) Films. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 2748–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.Y.; Xu, W.J.; Ji, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y. Research Progress on High Entropy Ceramic Materials. Mater. Prot. 2023, 56, 35–49+96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B. High-entropy alloys as a bold step forward in alloy development. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.K.; Li, T.T.; Wu, Y.Q.; Chen, J. Microstructure and Tribological Properties of Plasma-Sprayed CoCrFeNi-based High-Entropy Alloy Coatings Under Dry and Oil-Lubricated Sliding Conditions. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2021, 30, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Li, C.-L.; Hsueh, C.-H. Recent Progress on High-Entropy Films Deposited by Magnetron Sputtering. Crystals 2022, 12, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.-G.; Hong, S.J.; Yun, Y.; Ryu, J.-H.; Wang, F.; Kang, H.; Suh, D. Effect of Self-Incandescent Heating on Superconducting NbN Nanowire Yarn. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2411076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.F.; Xu, C.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. Effect of Nb-Content on the Corrosion Resistance of Co-Free High Entropy Alloys in Chloride Environment. Tungsten 2024, 4, 778–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Chen, Q.; Cui, X.; Ouyang, D. Nb-Induced Lattice Changes to Enhance Corrosion Resistance of Al0.5Ti3Zr0.5NbxMo0.2 High-Entropy Alloys. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashkarov, E.; Krotkevich, D.; Koptsev, M.; Ognev, S.; Svyatkin, L.; Travitzky, N.; Lider, A. Microstructure and Hydrogen Permeability of Nb–Ni–Ti–Zr–Co High-Entropy Alloys. Membranes 2022, 12, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Yang, P.; Jia, Y.; Jia, Y. Lattice Distortion Effects on Mechanical Properties in Nb–Ti–V–Zr Refractory Medium-Entropy Alloys. Materials 2025, 18, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malucelli, G. How to Reduce the Flammability of Plastics and Textiles through Surface Treatments: Recent Advances. Coatings 2022, 12, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, G.C.; Almeida, G.S.; Corrêa, D.O.G.; Zambuzzi, W.F.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Correa, D.R.N.; Grandini, C.R. Preparation and characterization of novel as-cast Ti-Mo-Nb alloys for biomedical applications. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Yang, X.; Lian, G.; Chen, C. Microstructure and Properties of Laser Cladding CoCrNi-Based Medium-Entropy Alloy Enhanced by Nb. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 5015–5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, P.R.T.; Valeriano, L.C.; Gallo, C.F.; Piorino Neto, F.; de Lima, N.B.; Souza, R.M.; Souza, G.B.; Mello, A.; Trava-Airoldi, V.J.; Nascimento, V.F. On Manufacturing Multilayer-Like Nanostructures Using Misorientation Gradients in PVD Films. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panjan, P.; Kek-Merl, D.; Čekada, M.; Panjan, M.; Drnovšek, A. Review of Growth Defects in Thin Films Prepared by PVD Techniques. Coatings 2020, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, V.; Stepanov, N.; Zherebtsov, S.; Salishchev, G. Structure and Properties of High-Entropy Nitride Coatings. Metals 2022, 12, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.K.; Soni, V.K.; Chandrakar, R.; Kumar, A. Influence of Refractory Elements on Mechanical Properties of High Entropy Alloys. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2021, 102, 2953–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, B.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, X.; Wan, Q.; Pohrebniak, O.; Zhang, J.; Pelenovich, V.; Yang, B. Machine Learning-Based Design of Superhard High-Entropy Nitride Coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 36911–36922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.H. Effects of Nb Addition on Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Nbx-CoCrFeMnNi High-Entropy Alloy Films. Coatings 2021, 11, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, T.; Zuo, B.; Bian, S.; Lu, K.; Zhao, L.; Yu, L.; Xu, J. Insight into the Mechanisms of Nitride Films with Excellent Hardness and Lubricating Performance: A Review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Dou, Z.; Liu, F. Effect of Modulation Period on the Microstructure and Tribological Properties of AlCrTiVNbN/TiSiN Nano Multilayer Films. Coatings 2025, 15, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jin, Y.; Bai, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Structure and Properties of NbN/MoN Nano-Multilayer Coatings Deposited by Magnetron Sputtering. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 729, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, H.R.; Yimnirun, R.; Limpijumnong, S. Surface Roughness and Its Effect on Adhesion and Tribological Performance of Magnetron Sputtered Nitride Coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Musil, J.; Hamza, A.V. Commentary on Using H/E and H3/E2 as Proxies for Coating Toughness and Wear Resistance. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 389, 125651. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, F.; Chen, L. Tribological Behaviors of Super-Hard TiAlN Coatings: Correlation of H/E and H3/E2 with Wear Performance. Materials 2022, 15, 4197. [Google Scholar]

- Smyrnova, K.; Čaplovicová, M.; Kusý, M.; Kozak, A.; Flock, D.; Kassymbaev, A.; Pogrebnjak, A.; Sahul, M.; Haršáni, M.; Beresnev, V.; et al. Composite Materials with Nanoscale Multilayer Architecture Based on Cathodic-Arc Evaporated WN/NbN Coatings. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 17247–17265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walunj, G.; Choudhari, A.; Digole, S.; Bearden, A.; Kolt, O.; Bari, P.; Borkar, T. Microstructure, Mechanical, and Tribological Behaviour of Spark Plasma Sintered TiN, TiC, TiCN, TaN, and NbN Ceramic Coatings on Titanium Substrate. Metals 2024, 14, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaprakash, N.; Yang, C.-H.; Prabu, G.; Balamurugan, K.G. Surface Alloying of FeCoCrNiMn Particles on Inconel-718 Using Plasma-Transferred Arc Technique: Microstructure and Wear Characteristics. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 28271–28285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, F.Y. Magnetron Sputtering Preparation of NiTiAlCrCoN Nanomultilayer Films and Their Cavitation Erosion Resistance. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Technology, Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, T.; Zhao, K. Tribological Behavior and Oxidation Mechanism of Ni-Based Coatings under High-Temperature Conditions. Tribol. Int. 2020, 146, 106222. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, S. Effect of Nb Content on Structure and Properties of (TiNbAl)N Coatings Deposited by Cathodic Arc Evaporation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126558. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, W.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, T. Microstructure and Tribological Behavior of Cr-Based Oxide Films Formed on Alloy Surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 476, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, P. Design of Strengthening and Toughening for Transition Metal Carbonitride-Based Films and Their Tribological Properties; Jilin University: Changchun, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Deposition Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Target–substrate spacing (cm) | 12 |

| Working pressure (Pa) | 0.3 |

| Deposition temperature (°C) | Room temperature |

| Ar flow (sccm) | 45 |

| N2 flow (sccm) | 30 |

| Bias voltage (V) | −100 |

| DC power (W) | 200 |

| Deposition time (min) | 180 |

| Abbr. | 2θ/(°) | Interplanar Distance/nm | FWHM/rad | Grain Size/nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nb0 | 43.60 | 0.2075 | 0.2097 | 0.6069 |

| Nb0.25 | 43.47 | 0.2081 | 0.1351 | 0.9423 |

| Nb0.5 | 43.47 | 0.2081 | 0.1167 | 1.0908 |

| Nb0.75 | 43.59 | 0.2075 | 0.2319 | 0.5489 |

| Nb1 | 43.60 | 0.2075 | 0.1803 | 0.7058 |

| Abbr. | Nb/at% | Co/at% | Ni/at% | Fe/at% | Cr/at% | N/at% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nb0 | 0.00 | 16.64 | 16.86 | 16.37 | 16.38 | 33.39 |

| Nb0.25 | 8.82 | 16.04 | 15.01 | 15.15 | 15.75 | 29.23 |

| Nb0.5 | 11.33 | 13.65 | 13.57 | 13.95 | 13.20 | 34.31 |

| Nb0.75 | 11.46 | 12.95 | 13.66 | 13.46 | 12.88 | 35.59 |

| Nb1 | 12.77 | 12.72 | 12.24 | 12.03 | 12.77 | 37.47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Si, L.; Wang, H.; Yan, H.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Ouyang, P.; Dou, Z.; Zheng, C. Effect of Nb Contents on Microstructure and Tribological Properties of FeCoCrNiNbxN Films. Lubricants 2025, 13, 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120522

Si L, Wang H, Yan H, Li X, Liu F, Ouyang P, Dou Z, Zheng C. Effect of Nb Contents on Microstructure and Tribological Properties of FeCoCrNiNbxN Films. Lubricants. 2025; 13(12):522. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120522

Chicago/Turabian StyleSi, Lina, Haoran Wang, Hongjuan Yan, Xiaona Li, Fengbin Liu, Peixuan Ouyang, Zhaoliang Dou, and Caili Zheng. 2025. "Effect of Nb Contents on Microstructure and Tribological Properties of FeCoCrNiNbxN Films" Lubricants 13, no. 12: 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120522

APA StyleSi, L., Wang, H., Yan, H., Li, X., Liu, F., Ouyang, P., Dou, Z., & Zheng, C. (2025). Effect of Nb Contents on Microstructure and Tribological Properties of FeCoCrNiNbxN Films. Lubricants, 13(12), 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120522