Radio-Frequency Searches for Dark Matter in Dwarf Galaxies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Radio Emissions from Dark Matter

2.1. Electron Source Functions from DM Annihilation/Decay

2.2. DM Halos of Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies

2.3. Diffusion of Secondary Electrons

2.4. Synchrotron Emission

3. Deep Radio Searches for Dark Matter Emissions

4. Search Results

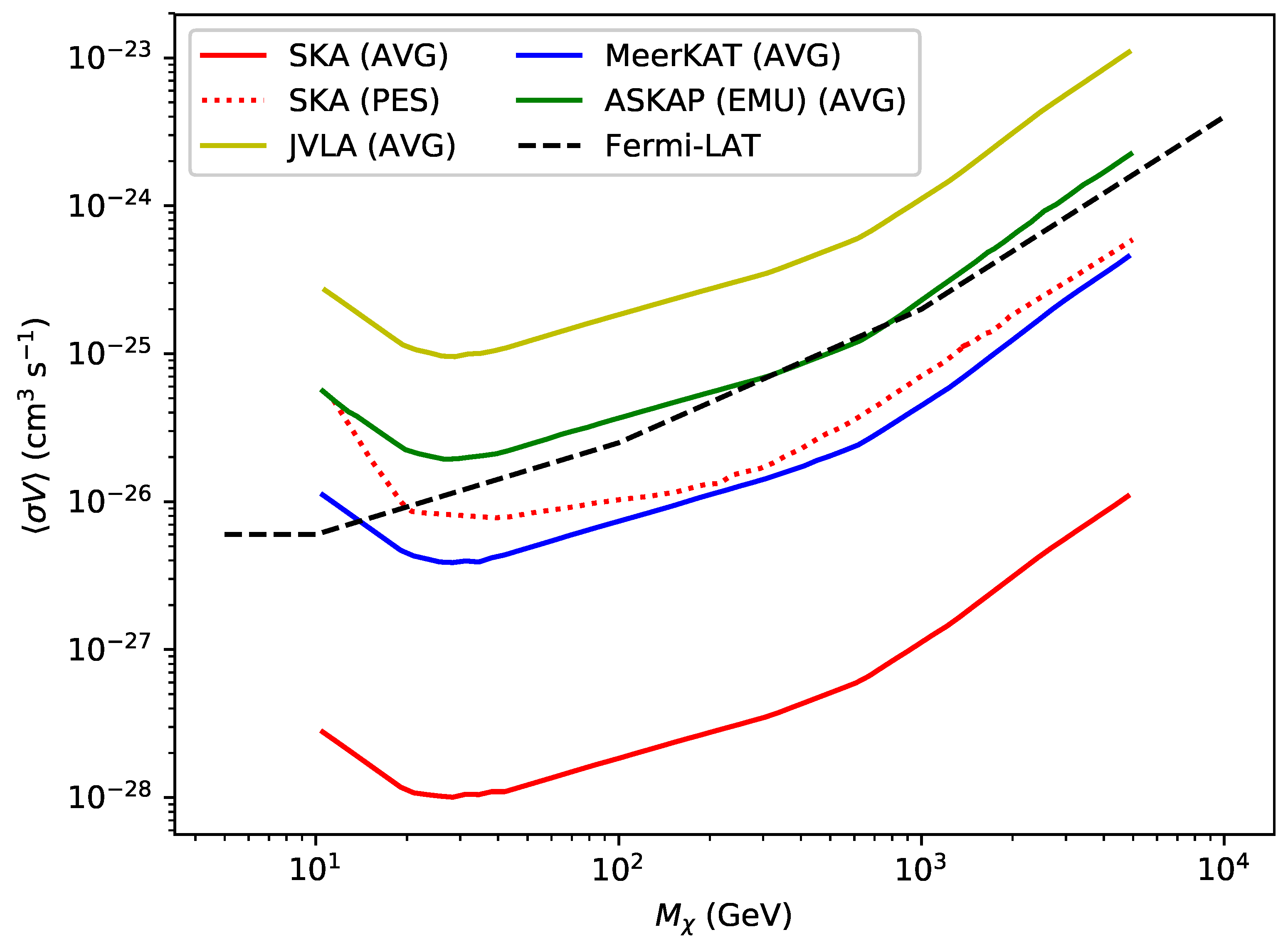

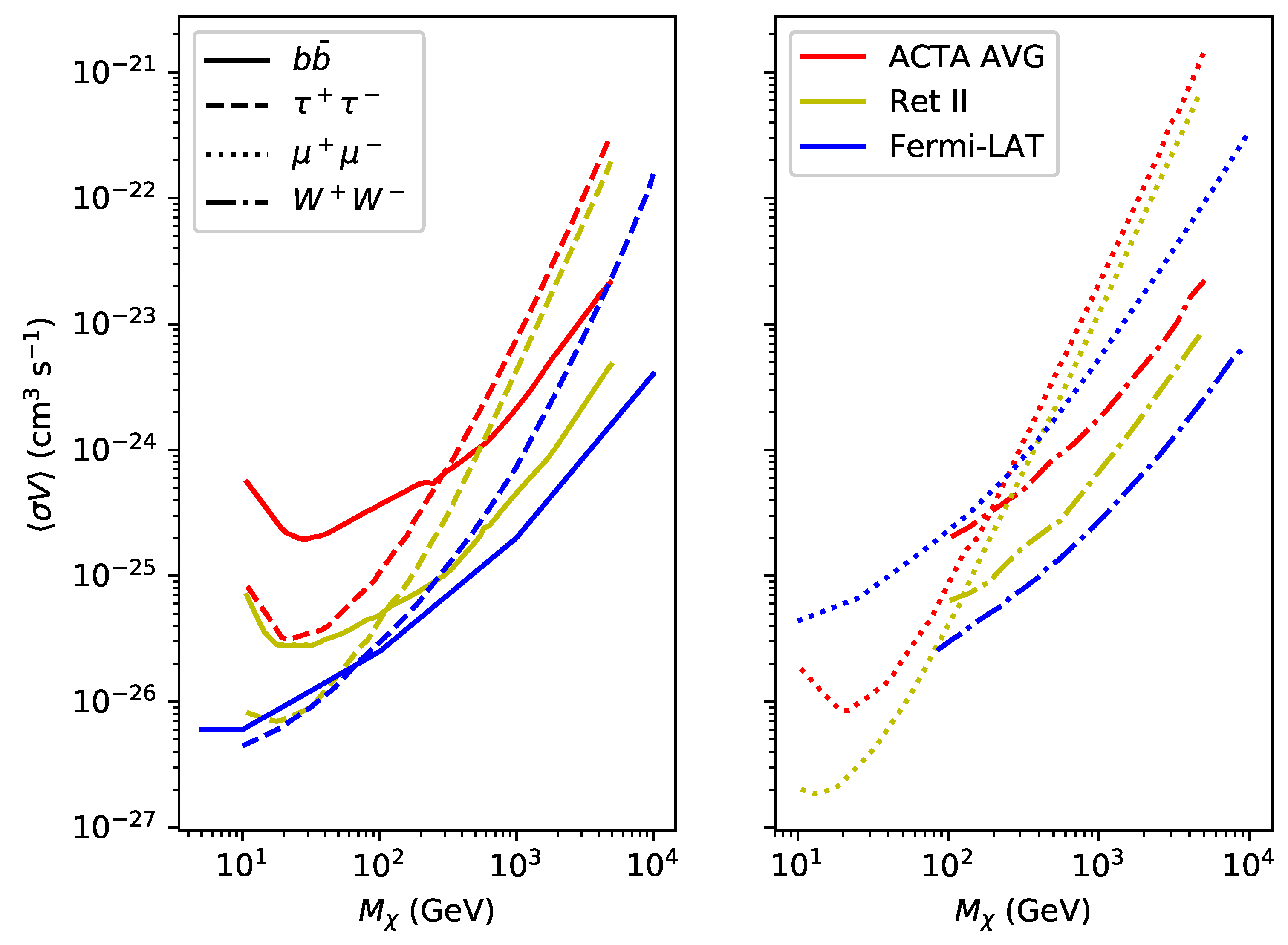

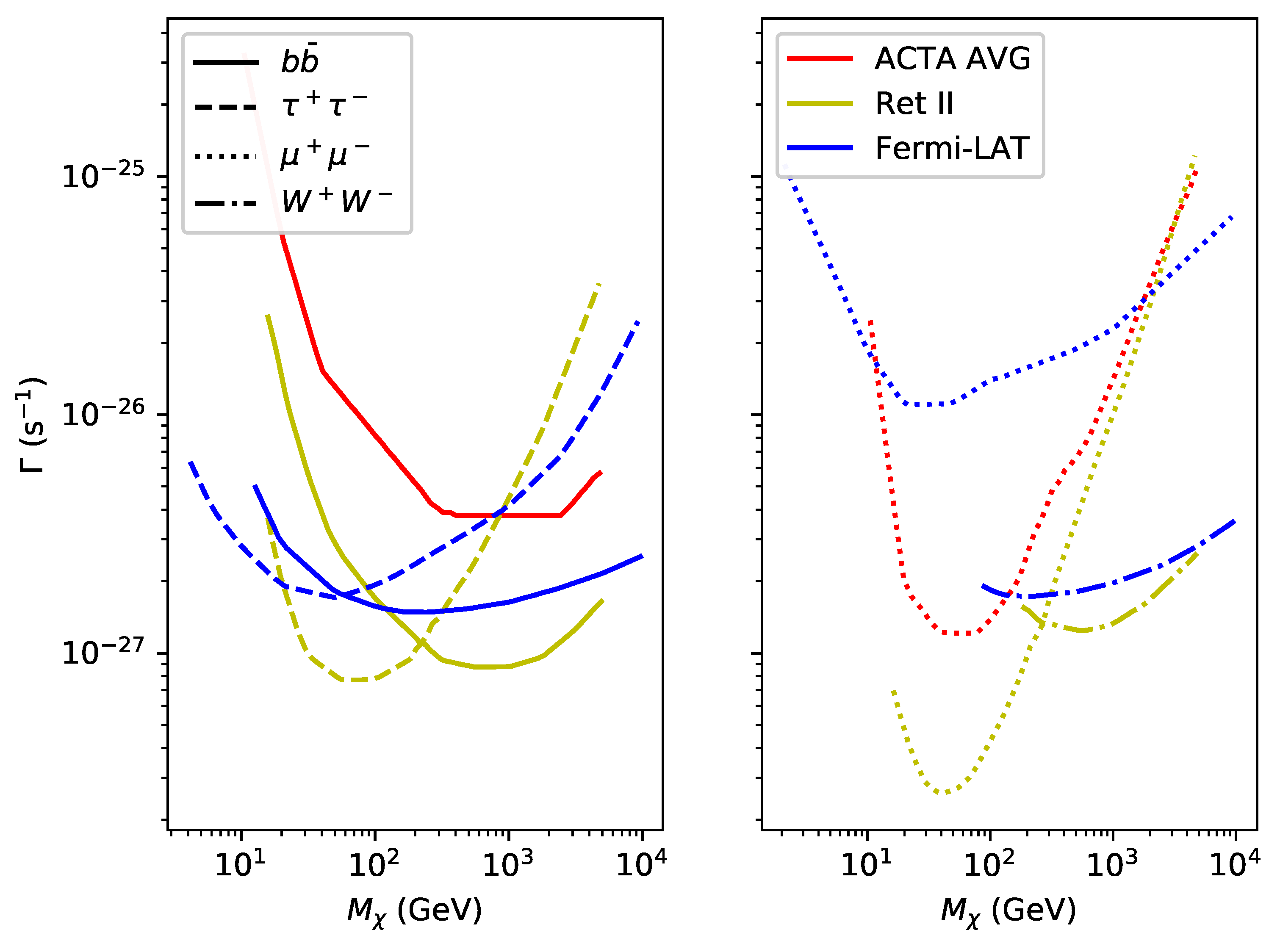

5. Future Prospects

6. Outlook

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DM | Dark Matter |

| dSph | Dwarf spheroidal galaxy |

| SKA | Square Kilometre Array |

| ATCA | Australian Telescope Compact Array |

| GBT | Green Bank Telescope |

| JVLA | Jansky Very Large Array |

| ASKAP | Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder |

| EMU | Evolutionary Map of the Universe |

| KAT | Karoo Array Telescope |

| LOFAR | LOw Frequency ARray |

References

- Mateo, M. Dwarf galaxies of the Local Group. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 1998, 36, 435–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, C. Particle dark matter constraints from the Draco dwarf galaxy. Phys. Rev. D 2002, 66, 023509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profumo, S.; Kamionkowski, M. Dark matter and the cactus gamma-ray excess from draco. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood, W.B.; Abdo, A.A.; Ackermann, M.; Althouse, W.; Anderson, B.; Axelsson, M.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Band, D.L.; Barbiellini, G.; et al. for the Fermi/LAT collaboration. The Large Area Telescope on the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope Mission. Astrophys. J. 2009, 697, 1071–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Albert, A.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Barbiellini, G.; Bastieri, D.; Bechtol, K.; Bellazzini, R.; Blandford, R.D.; Bloom, E.D.; et al. Search for Dark Matter Satellites using the FERMI-LAT. Astrophys. J. 2012, 747, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Albert, A.; Anderson, B.; Atwood, W.B.; Baldini, L.; Barbiellini, G.; Bastieri, D.; Bechtol, K.; Bellazzini, R.; Bissaldi, E.; et al. Searching for Dark Matter Annihilation from Milky Way Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies with Six Years of Fermi Large Area Telescope Data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 231301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geringer-Sameth, A.; Walker, M.G.; Koushiappas, S.M.; Koposov, S.E.; Belokurov, V.; Torrealba, G.; Evans, N.W. Indication of Gamma-Ray Emission from the Newly Discovered Dwarf Galaxy Reticulum II. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 081101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liang, Y.F.; Duan, K.K.; Shen, Z.Q.; Huang, X.; Li, X.; Fan, Y.Z.; Liao, N.H.; Feng, L.; Chang, J. Search for gamma-ray emission from eight dwarf spheroidal galaxy candidates discovered in Year Two of Dark Energy Survey with Fermi-LAT data. Phys. Rev. 2016, D93, 043518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Duan, K.K.; Liang, Y.F.; Xia, Z.Q.; Shen, Z.Q.; Li, X.; Liao, N.H.; Feng, L.; Yuan, Q.; Fan, Y.Z.; et al. Search for gamma-ray emission from the nearby dwarf spheroidal galaxies with 9 years of Fermi-LAT data. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 97, 122001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharonian, F. Observations of the Sagittarius Dwarf galaxy by the H.E.S.S. experiment and search for a Dark Matter signal. Astropart. Phys. 2008, 29, 55–62, Erratum in 2010, 33, 274–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowski, A.; Acero, F.; Aharonian, F.; Akhperjanian, A.G.; Anton, G.; Barnacka, A.; De Almeida, U.B.; Bazer-Bachi, A.R.; Becherini, Y.; Becker, J.; et al. H.E.S.S. constraints on dark matter annihilations towards the sculptor and carina dwarf galaxies. Astropart. Phys. 2011, 34, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowski, A.; Aharonian, F.; Benkhali, F.A.; Akhperjanian, A.G.; Angüner, E.; Backes, M.; Balenderan, S.; Balzer, A.; Barnacka, A.; Becherini, Y.; et al. Search for dark matter annihilation signatures in H.E.S.S. observations of Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 112012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, H.; Aharonian, F.; Benkhali, F.A.; Angüner, E.O.; Arakawa, M.; Arcaro, C.; Armand, C.; Arrieta, M.; Backes, M.; Barnard, M.; et al. Searches for gamma-ray lines and ’pure WIMP’ spectra from Dark Matter annihilations in dwarf galaxies with H.E.S.S. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, A.; Alfaro, R.; Alvarez, C.; Álvarez, J.D.; Arceo, R.; Arteaga-Velázquez, J.C.; Rojas, D.A.; Solares, H.A.; Bautista-Elivar, N.; Becerril, A.; et al. Dark Matter Limits from Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies with The HAWC Gamma-Ray Observatory. Astrophys. J. 2018, 853, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, U.; Giovanardi, C.; Altschuler, D.R.; Wunderlich, E. A sensitive radio continuum survey of low surface brightness dwarf galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 1992, 255, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, E.W.; Turner, M.S. The Early Universe. Front. Phys. 1990, 69, 115–152. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, A.W.; Moskalenko, I.V. Propagation of cosmic-ray nucleons in the galaxy. Astrophys. J. 1998, 509, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perley, R.A.; Chandler, C.J.; Butler, B.J.; Wrobel, J.M. The Expanded Very Large Array: A New Telescope for New Science. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2011, 739, L1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewdney, P.; Turner, W.; Millenaar, R.; McCool, R.; Lazio, J.; Cornwell, T. SKA Baseline Design Document 2012. Available online: http://www.skatelescope.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/SKA-TEL-SKO-DD-001-1_BaselineDesign1.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- Booth, R.; de Blok, W.; Jonas, J.; Fanaroff, B. MeerKAT Key Project Science, Specifications, and Proposals. arXiv, 2009; arXiv:0910.2935. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, D.; Allison, J.R.; Bannister, K.; Bell, M.E.; Bignall, H.E.; Chippendale, A.P.; Edwards, P.G.; Harvey-Smith, L.; Hegarty, S.; Heywood, I.; et al. The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder: Performance of the Boolardy Engineering Test Array. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2016, 33, e042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haarlem, M.P.; Wise, M.W.; Gunst, A.W.; Heald, G.; McKean, J.P.; Hessels, J.W.; De Bruyn, A.G.; Nijboer, R.; Swinbank, J.; Fallows, R.; et al. LOFAR: The Low-Frequency Array. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 556, A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colafrancesco, S.; Profumo, S.; Ullio, P. Detecting dark matter WIMPs in the Draco dwarf: A multi-wavelength perspective. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 75, 023513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spekkens, K.; Mason, B.S.; Aguirre, J.E.; Nhan, B. A Deep Search for Extended Radio Continuum Emission From Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies: Implications for Particle Dark Matter. Astrophys. J. 2013, 773, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, A.; Peterson, J.B.; Voytek, T.C.; Spekkens, K.; Mason, B.; Aguirre, J.; Willman, B. Bounds on Dark Matter Properties from Radio Observations of Ursa Major II using the Green Bank Telescope. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 88, 083535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, J.J.; Cotton, W.D.; Greisen, E.W.; Yin, Q.F.; Perley, R.A.; Taylor, G.B.; Broderick, J.J. The NRAO VLA Sky survey. Astron. J. 1998, 115, 1693–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regis, M.; Richter, L.; Colafrancesco, S.; Massardi, M.; de Blok, W.J.G.; Profumo, S.; Orford, N. Local Group dSph radio survey with ATCA – I: Observations and background sources. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 448, 3731–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regis, M.; Richter, L.; Colafrancesco, S.; Profumo, S.; de Blok, W.J.G.; Massardi, M. Local Group dSph radio survey with ATCA—II. Non-thermal diffuse emission. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 448, 3747–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regis, M.; Colafrancesco, S.; Profumo, S.; de Blok, W.; Massardi, M.; Richter, L. Local Group dSph radio survey with ATCA (III): Constraints on particle dark matter. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2014, 2014, 016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regis, M.; Richter, L.; Colafrancesco, S. Dark matter in the Reticulum II dSph: A radio search. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2017, 2017, 025. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J.F.; Frenk, C.S.; White, S.D.M. The Structure of cold dark matter halos. Astrophys. J. 1996, 462, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkert, A. The Structure of dark matter halos in dwarf galaxies. Astrophys. J. Lett. 1995, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einasto, J. On Galactic Descriptive Functions. Astron. Nachr. 1968, 291, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.G.; Mateo, M.; Olszewski, E.W.; Peñarrubia, J.; Evans, N.W.; Gilmore, G. A Universal Mass Profile for Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies? Astrophys. J. 2009, 704, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.J.; Simon, J.D.; Fabricius, M.H.; van den Bosch, R.C.; Barentine, J.C.; Bender, R.; Gebhardt, K.; Hill, G.J.; Murphy, J.D.; Swaters, R.A.; et al. Dwarf Galaxy Dark Matter Density Profiles Inferred from Stellar and Gas Kinematics. Astrophys. J. 2014, 789, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colafrancesco, S.; Profumo, S.; Ullio, P. Multi-frequency analysis of neutralino dark matter annihilations in the Coma cluster. Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 455, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colafrancesco, S.; Marchegiani, P.; Beck, G. Evolution of Dark Matter Halos and their Radio Emissions. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evoli, C.; Gaggero, D.; Grasso, D.; Maccione, L. Cosmic ray nuclei, antiprotons and gamma rays in the galaxy: A new diffusion model. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2008, 2008, 018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltz, E.A.; Edsjö, J. Positron propagation and fluxes from neutralino annihilation in the halo. Phys. Rev. D 1998, 59, 023511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltz, E.A.; Wai, L. Diffuse inverse Compton and synchrotron emission from dark matter annihilations in galactic satellites. Phys. Rev. D 2004, 70, 023512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colafrancesco, S.; Blasi, S. Clusters of Galaxies and the Diffuse Gamma Ray Background. Astropart. Phys. 1998, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longair, M.S. High Energy Astrophysics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jeltema, E.; Profumo, S. Searching for Dark Matter with X-ray Observations of Local Dwarf Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2008, 686, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sault, R.J.; Teuben, P.J.; Wright, M.C. A retrospective view of Miriad. In Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series Vol. 77, Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems IV; Shaw, R.A., Payne, H.E., Hayes, J.J.E., Eds.; Astronomical Society of the Pacific: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995; p. 433. [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, E.; Arnouts, S. SExtractor: Software for source extraction. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 1996, 117, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandoni, I.; Gregorini, L.; Parma, P.; De Ruiter, H.R.; Vettolani, G.; Wieringa, M.H.; Ekers, R.D. The ATESP radio survey I. Survey description, observations and data reduction. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. 2000, 146, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, A.R.; Alberts, T.; Armstrong, R.P.; Barta, A.; Bauermeister, E.F.; Bester, H.; Blose, S.; Booth, R.S.; Botha, D.H.; Buchner, S.J.; et al. Engineering and science highlights of the KAT-7 radio telescope. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 460, 1664–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnivard, V.; Combet, C.; Maurin, D.; Geringer-Sameth, A.; Koushiappas, S.M.; Walker, M.G.; Mateo, M.; Olszewski, E.W.; Bailey, J.I., III. Dark matter annihilation and decay profiles for the Reticulum II dwarf spheroidal galaxy. Astrophys. J. 2015, 808, L36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baring, M.G.; Ghosh, T.; Queiroz, F.S.; Sinha, K. New limits on the dark matter lifetime from dwarf spheroidal galaxies using Fermi-LAT. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, N.; Reuben, R.; Sigl, G.; Tytgat, M.; Vollmann, M. Synchrotron emission from dark matter in galactic subhalos. A look into the Smith cloud. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2016, 2016, 021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, E.; Jeltema, T.E.; Splettstoesser, M.; Profumo, S. Synchrotron Emission from Dark Matter Annihilation: Predictions for Constraints from Non-detections of Galaxy Clusters with New Radio Surveys. Astrophys. J. 2017, 839, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, R.P.; Hopkins, A.M.; Afonso, J.; Brown, S.; Condon, J.J.; Dunne, L.; Feain, I.; Hollow, R.; Jarvis, M.; Johnston-Hollitt, M.; et al. EMU: Evolutionary Map of the Universe. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2011, 28, 215–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, T.; Abdalla, F.B.; Aleksić, J.; Allam, S.; Amara, A.; Bacon, D.; Balbinot, E.; Banerji, M.; Bechtol, K.; Benoit-Lévy, A.; et al. The Dark Energy Survey: More than dark energy—An overview. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 460, 1270–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.C.; Schmidt, B.P.; Bessell, M.S.; Conroy, P.G.; Francis, P.; Granlund, A.; Kowald, E.; Oates, A.P.; Martin-Jones, T.; Preston, T.; et al. SkyMapper and the Southern Sky Survey. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2007, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abell, P.A.; Burke, D.L.; Hamuy, M.; Nordby, M.; Axelrod, T.S.; Monet, D.; Vrsnak, B.; Thorman, P.; Ballantyne, D.R.; Simon, J.D.; et al. LSST Science Book, Version 2.0. arXiv, 2009; arXiv:0912.0201. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beck, G. Radio-Frequency Searches for Dark Matter in Dwarf Galaxies. Galaxies 2019, 7, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies7010016

Beck G. Radio-Frequency Searches for Dark Matter in Dwarf Galaxies. Galaxies. 2019; 7(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies7010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeck, Geoff. 2019. "Radio-Frequency Searches for Dark Matter in Dwarf Galaxies" Galaxies 7, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies7010016

APA StyleBeck, G. (2019). Radio-Frequency Searches for Dark Matter in Dwarf Galaxies. Galaxies, 7(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies7010016