Reinforcement Learning-Driven Framework for High-Precision Target Tracking in Radio Astronomy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Positioning Control System

2.2. Receiver System

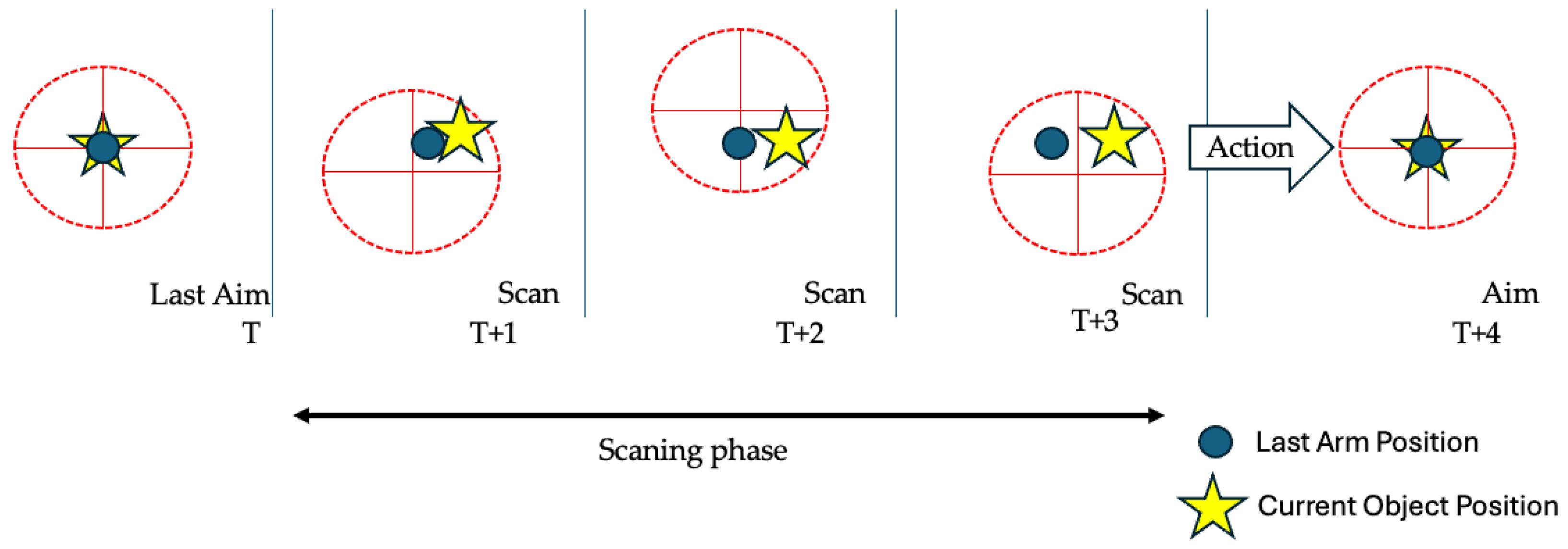

2.3. Tracking Control System

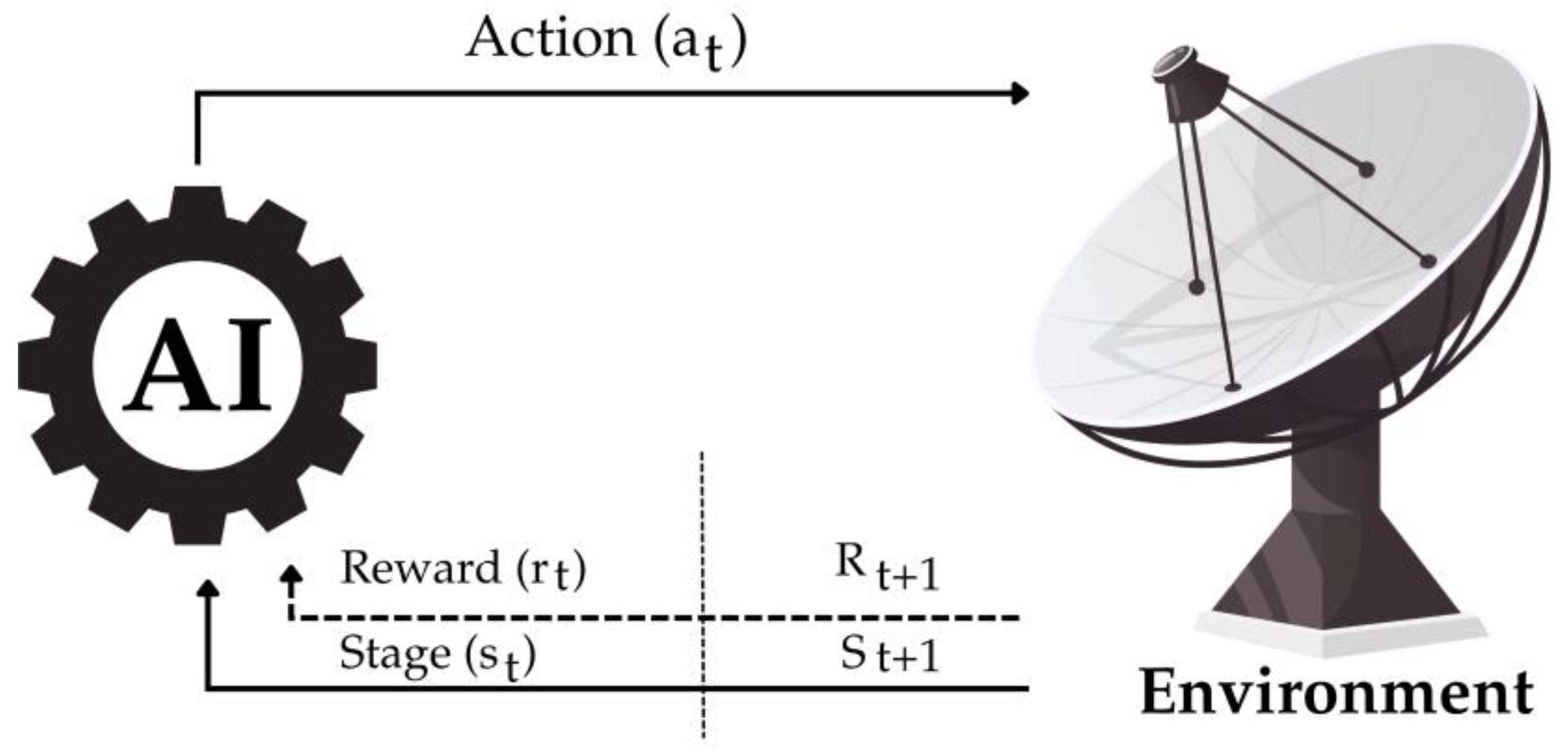

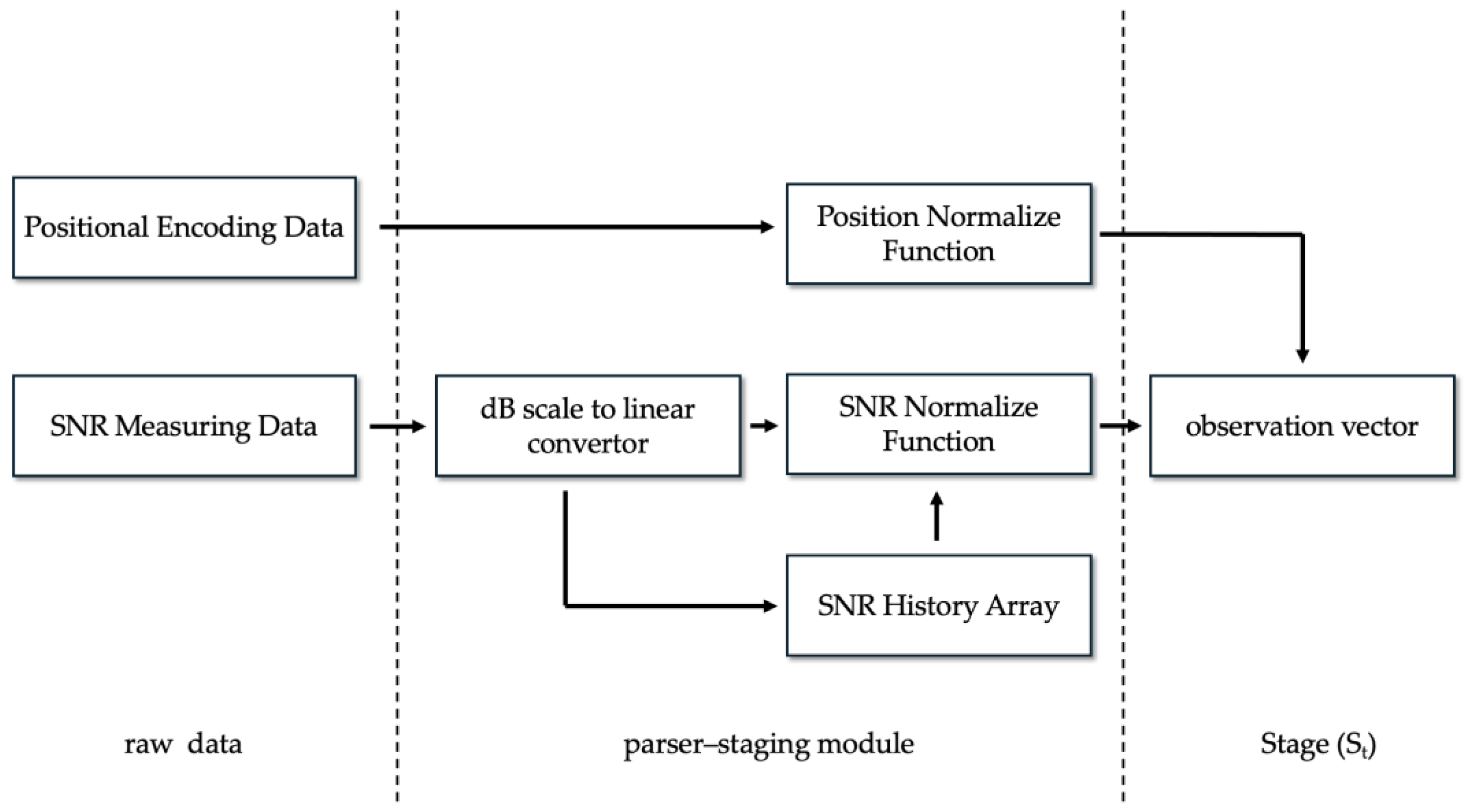

2.4. Reinforcement Learning Framework

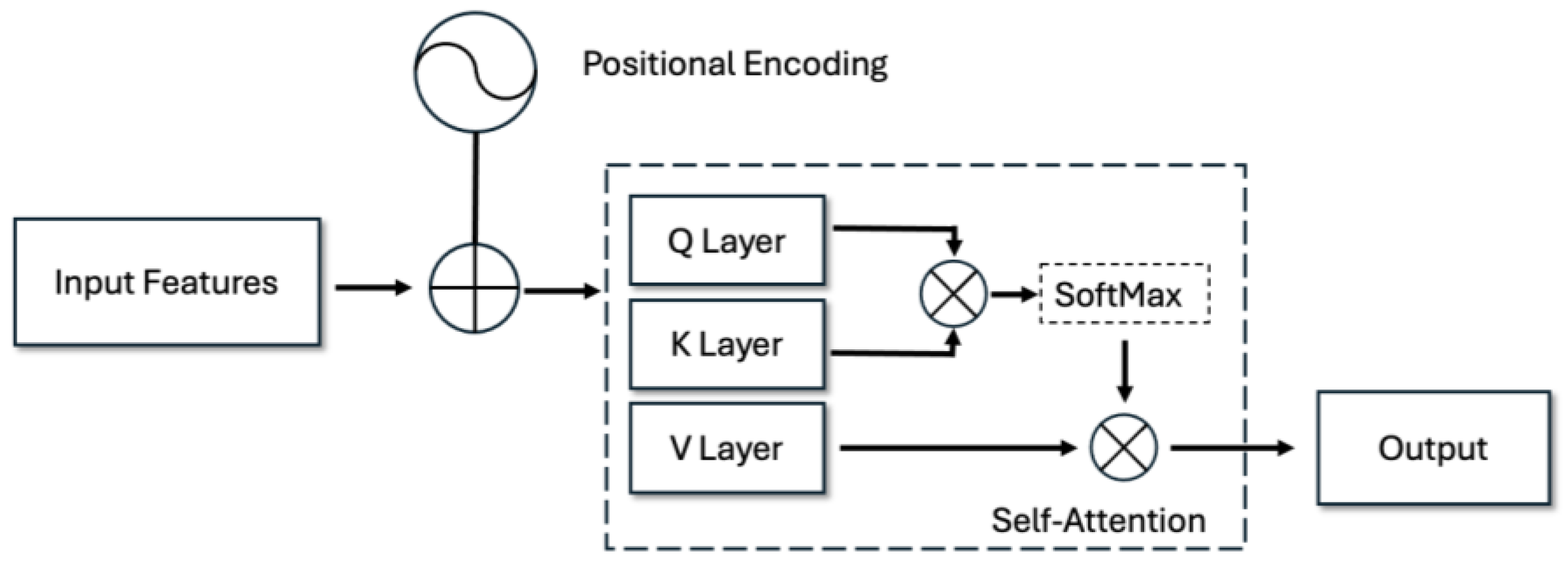

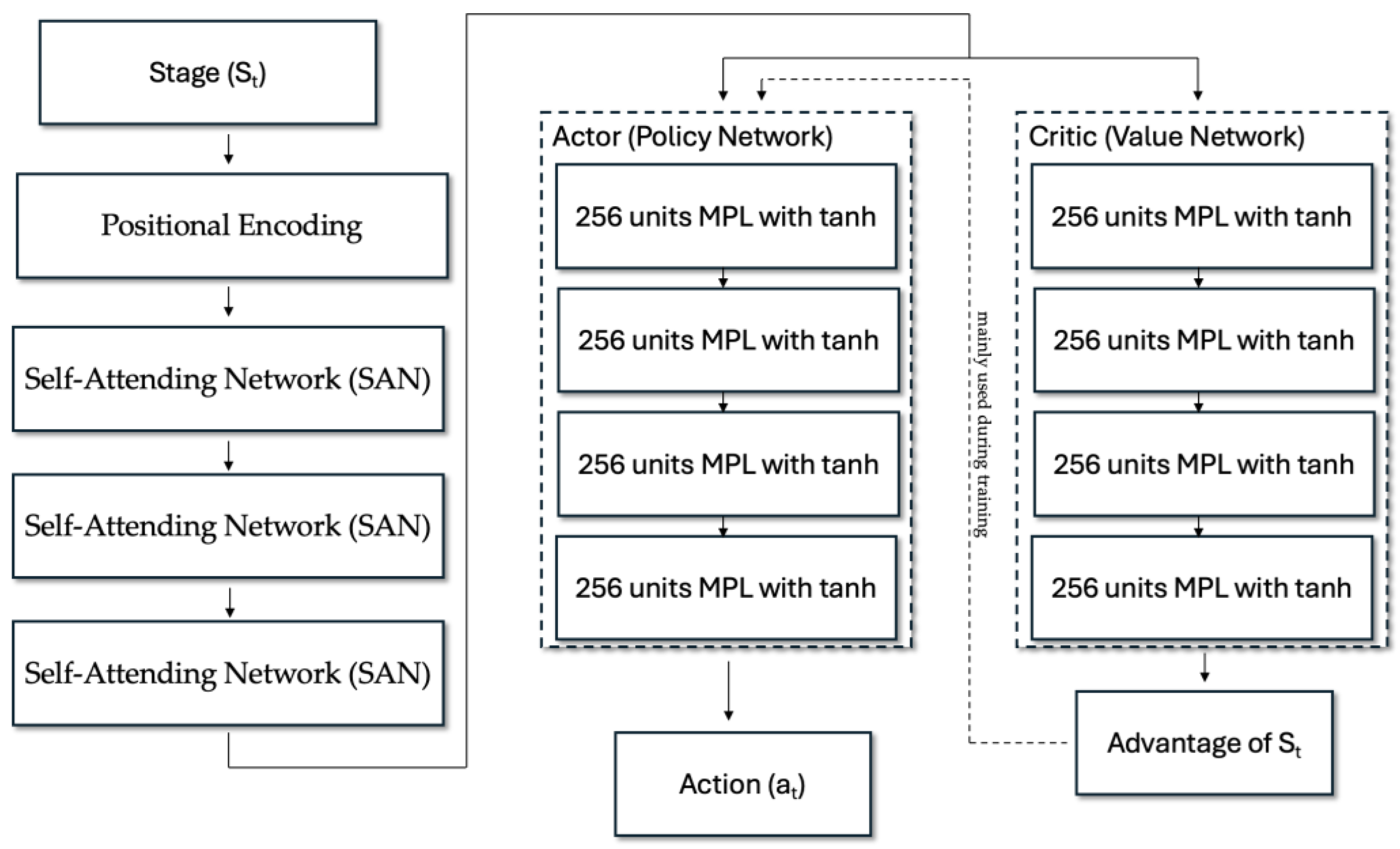

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) Algorithm

2.5. Hyperparameter Optimization

3. Experimental Setup and Design

3.1. Experimental Setup on the Renovated 12-m Radio Telescope at KMITL

3.2. Testing and Evaluation Protocols

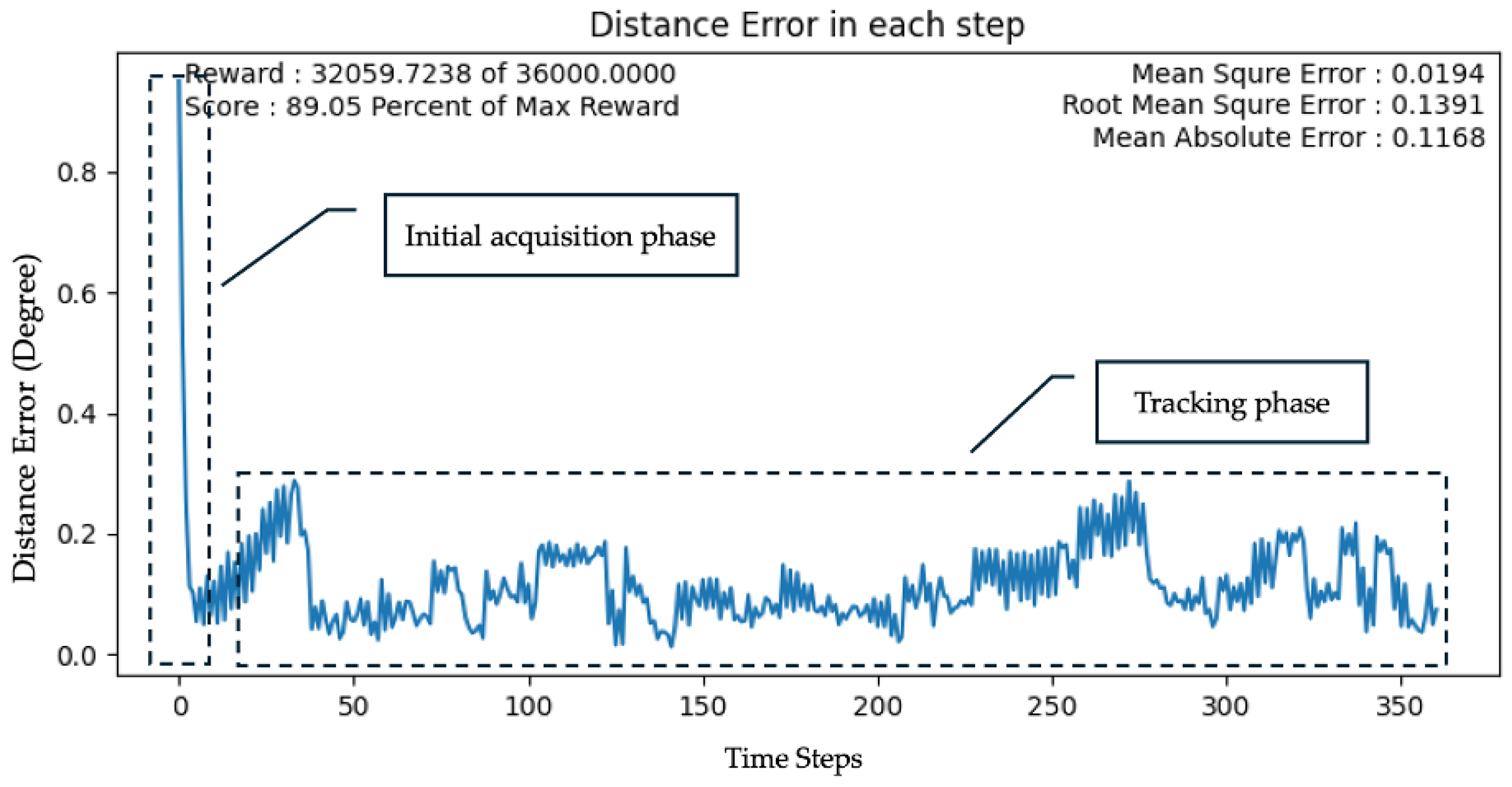

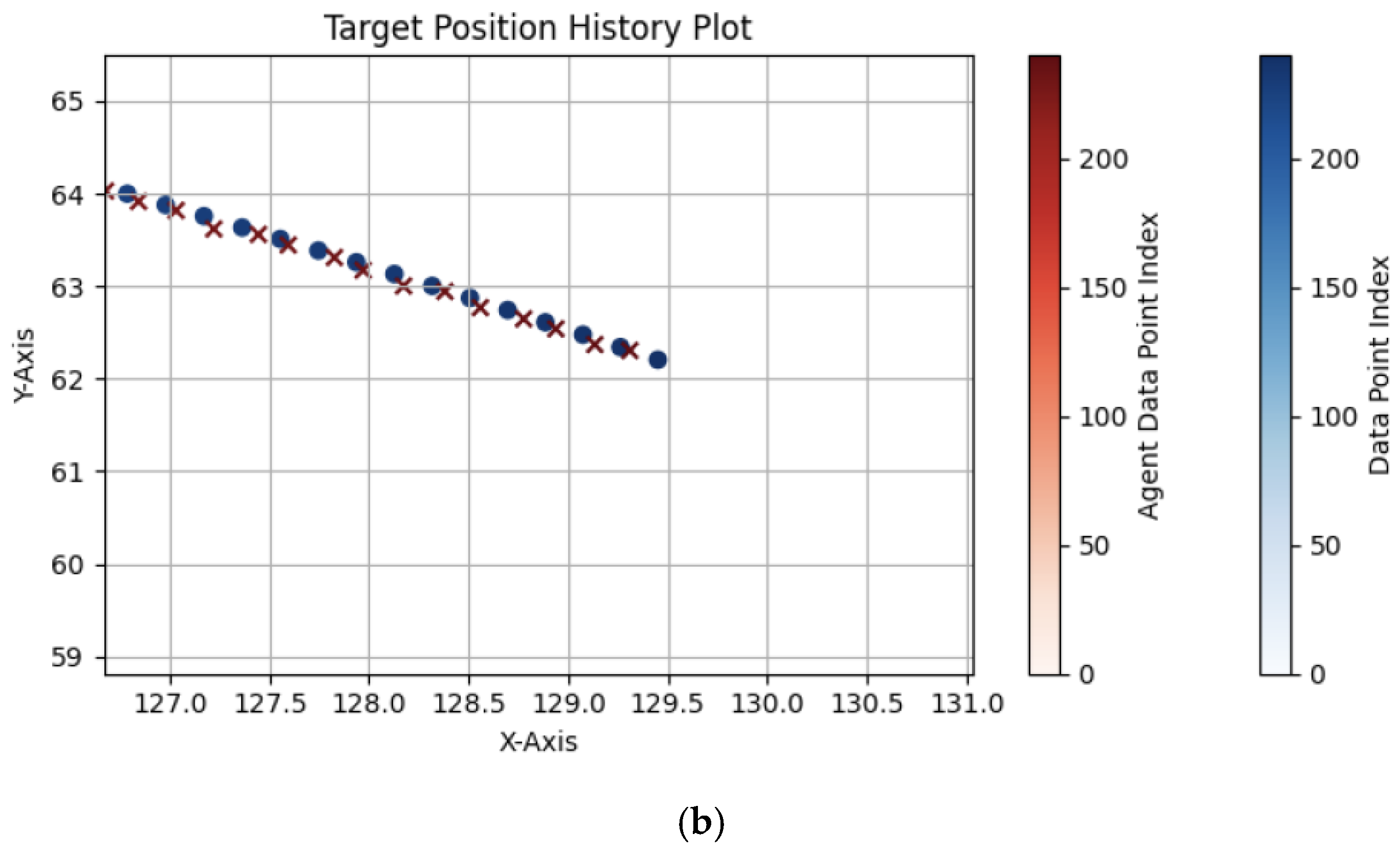

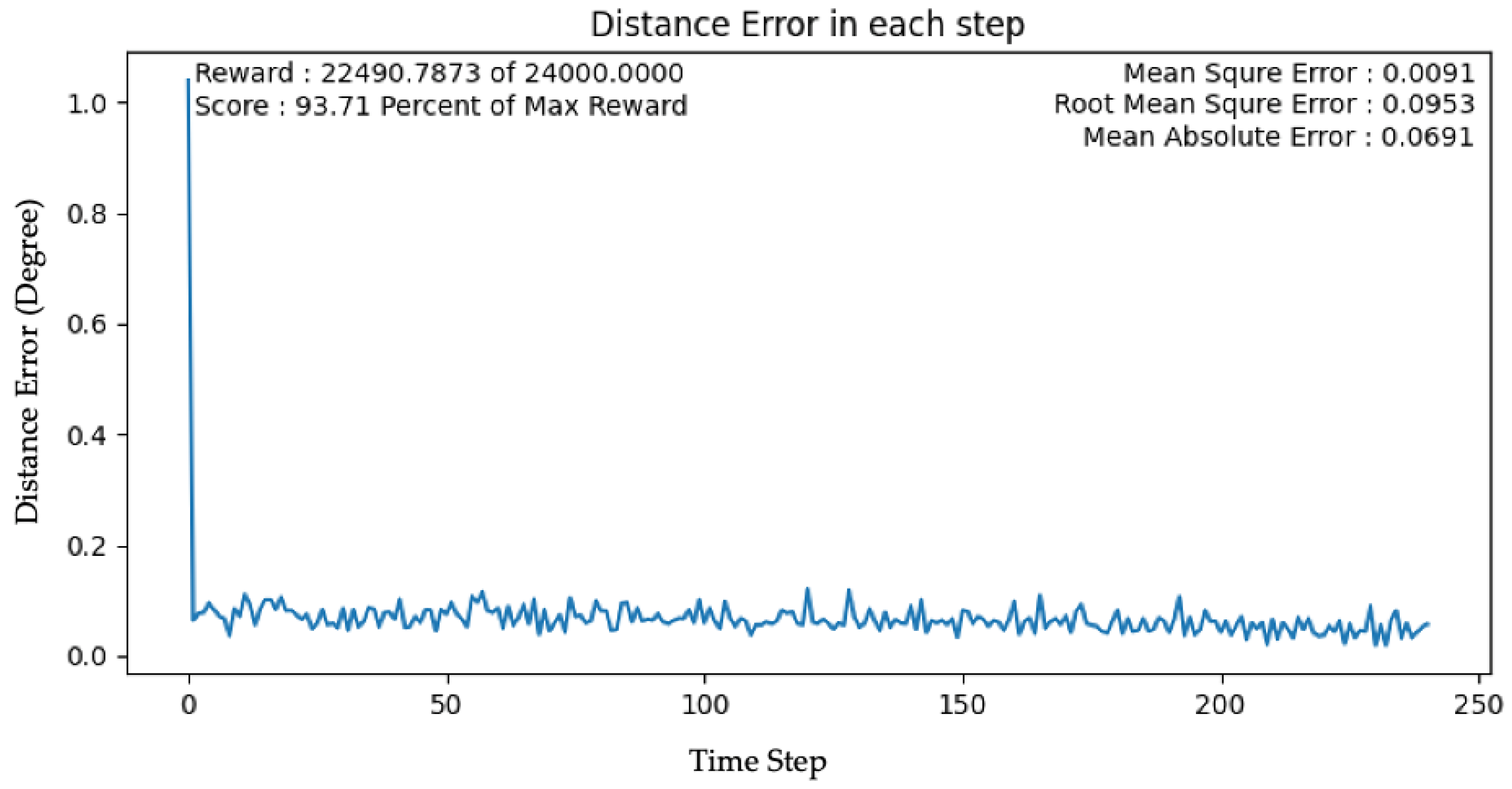

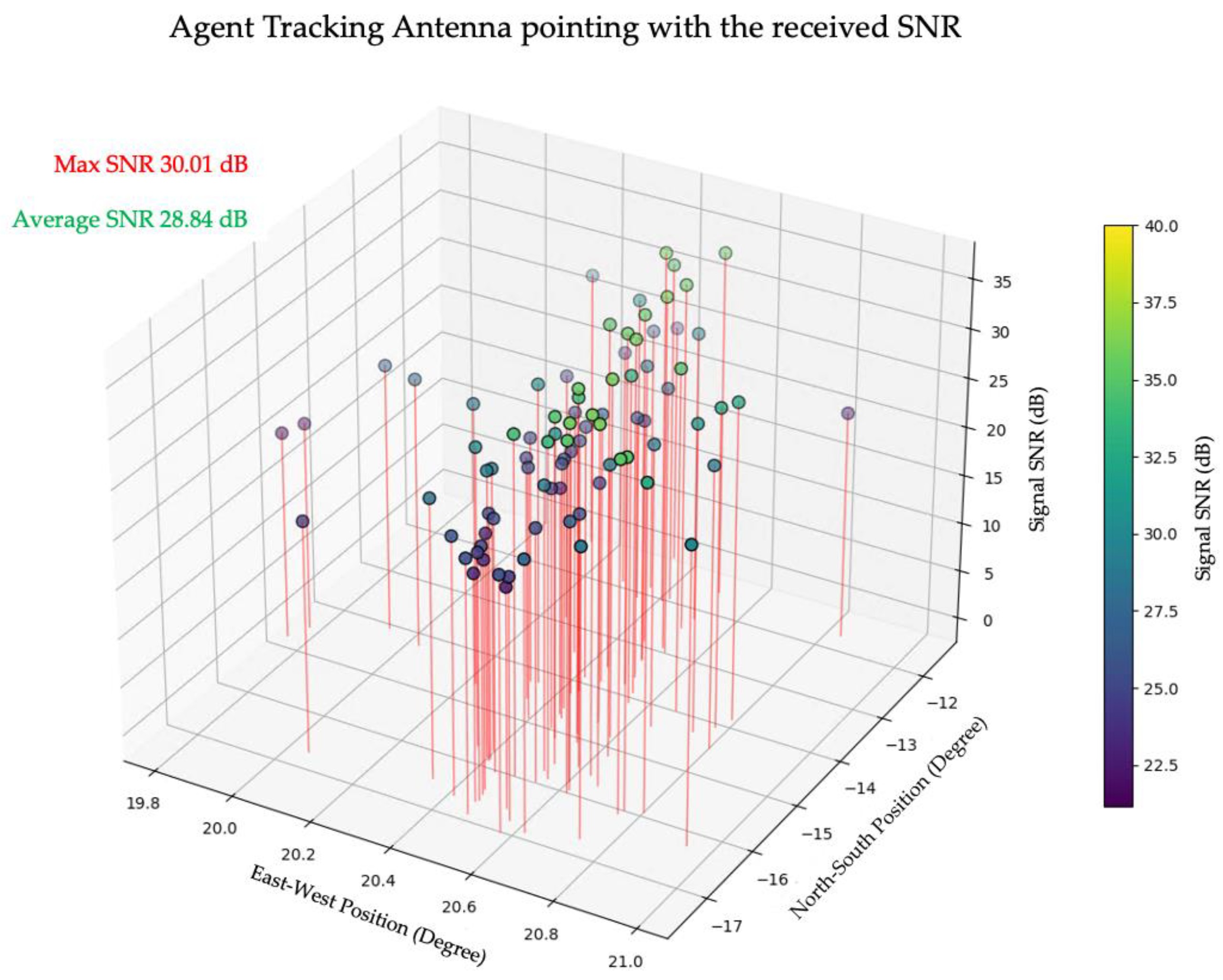

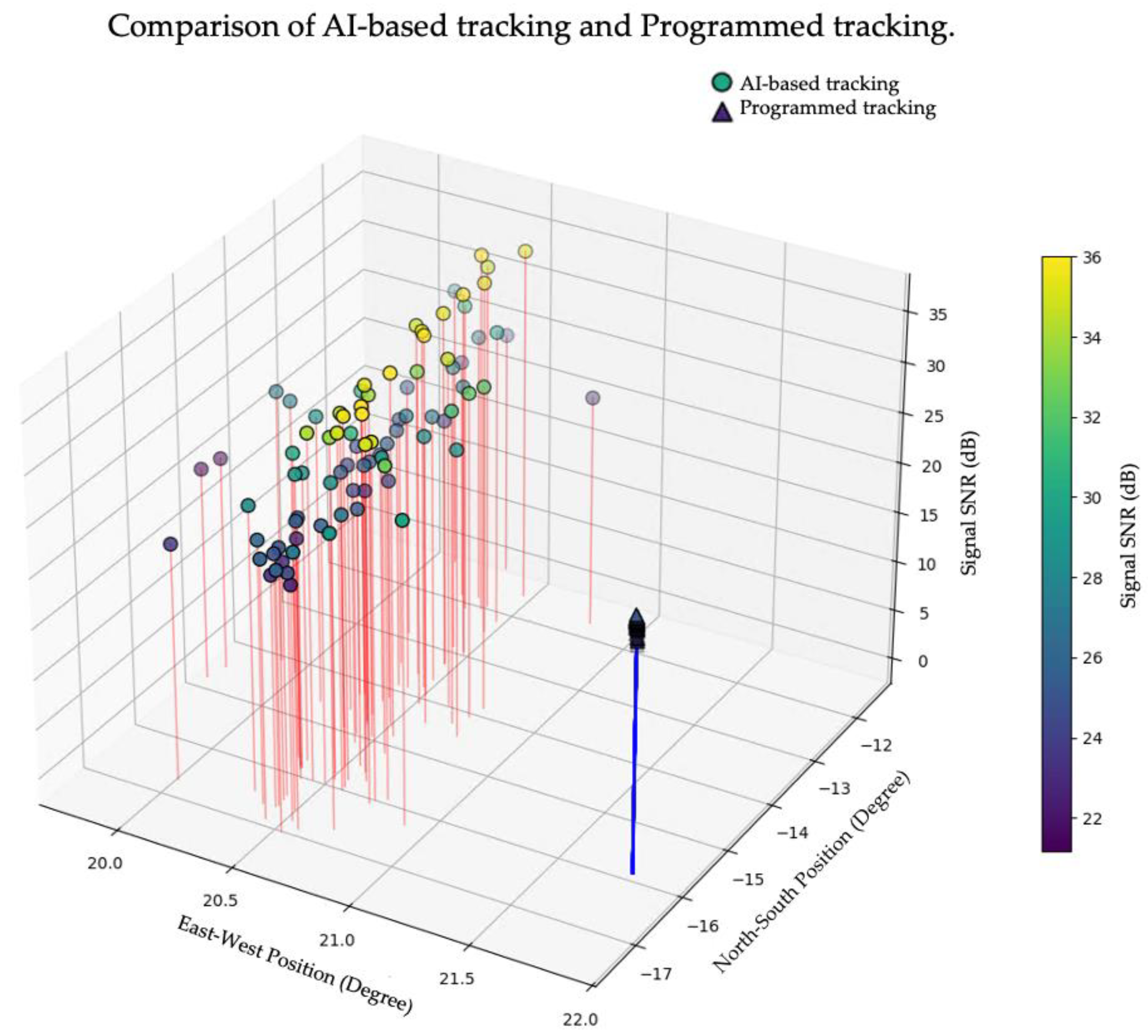

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davies, R.; Kasper, M. Adaptive optics for astronomy. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 50, 305–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Masui, K.W.; Scott, D. The spectrum of the universe. Appl. Spectrosc. 2018, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutinjo, A.T.; Colegate, T.M.; Wayth, R.B.; Hall, P.J.; de Lera Acedo, E.; Booler, T.; Faulkner, A.J.; Feng, L.; Hurley-Walker, N.; Juswardy, B.; et al. Characterization of a low-frequency radio astronomy prototype array in Western Australia. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2015, 63, 5433–5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazio, T.J.W.; Kimball, A.; Barger, A.J.; Brandt, W.N.; Chatterjee, S.; Clarke, T.E.; Condon, J.J.; Dickman, R.L.; Hunyh, M.T.; Jarvis, M.J.; et al. Radio astronomy in LSST era. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2014, 126, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Cornwell, T.J.; Golap, K. Solving for the Antenna Based Pointing Errors. EVLA Memo #84, National Radio Astronomy Observatory. 2004. Available online: http://www.aoc.nrao.edu/evla/geninfo/memoseries/evlamemo84.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Naval Observatory Vector Astrometry Software. Available online: https://aa.usno.navy.mil/software/novas_info (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Stellarium. Stellarium. Available online: http://stellarium.org (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Mokhun, S.; Fedchyshyn, O.; Kasianchuk, M.; Chopyk, P.; Basistyi, P.; Matsyuk, V. Stellarium software as a means of development of students’ research competence while studying physics and astronomy. In Proceedings of the 2022 12th International Conference on Advanced Computer Information Technologies (ACIT), Ruzomberok, Slovakia, 26–28 September 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 587–591. [Google Scholar]

- Meeus, J.H. Astronomical Algorithms; Willmann-Bell, Incorporated: Virginia, NV, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, C.; Shi, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Luo, D. The analysis and verification of IMT-2000 base station interference characteristics in the FAST radio quiet zone. Universe 2023, 9, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Huang, S.; Hu, H.; Yang, C. A Software for RFI Analysis of Radio Environment around Radio Telescope. Universe 2023, 9, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, P.; Olabisi, F. Interference protection of radio astronomy services using cognitive radio spectrum sharing models. In Proceedings of the 2015 European Conference on Networks and Communications (EuCNC), Paris, France, 29 June–2 July 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Küçük, I.; Üler, I.; Öz, Ş.; Onay, S.; Özdemir, A.R.; Gülşen, M.; Sarıkaya, M.; Daǧtekin, N.D.; Özeren, F.F. Site selection for a radio astronomy observatory in Turkey: Atmospherical, meteorological, and radio frequency analyses. Exp. Astron. 2012, 33, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xue, F.; Wang, H.; Yi, L. Measurement and Correction of Pointing Error Caused by Radio Telescope Alidade Deformation based on Biaxial Inclination Sensor. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.N.; Chung, A. An intelligent design for a PID controller for nonlinear systems. Asian J. Control 2016, 18, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, R.D.; Givi, H.; Crunteanu, D.-E.; Cican, G. Adaptive predictive functional control of XY pedestal for LEO satellite tracking using Laguerre functions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vicente, P.; Bolaño, R.; Barbas, L. The control system of the 40 m radiotelescope. In Proceedings of the IX Scientific Meeting of the Spanish Astronomical Society Held on September, Madrid, Spain, 13–17 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Tian, Y. Trajectory tracking control of XY table using sliding mode adaptive control based on fast double power reaching law. Asian J. Control 2016, 18, 2263–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, G. A Simulative Study on Active Disturbance Rejection Control (ADRC) as a Control Tool for Practitioners. Electronics 2013, 2, 246–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yung, K.L.; Cheng, K. A learning scheme for low-speed precision tracking control of hybrid stepping motors. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2006, 11, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Zhou, Q.; Li, T.; Li, H. Adaptive reinforcement learning neural network control for uncertain nonlinear system with input saturation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 3433–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Luo, W. Reference trajectory modification based on spatial iterative learning for contour control of two-axis NC systems. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 25, 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Pu, Z.; Hu, J.; Wang, X.; Ke, R. Safe, efficient, and comfortable velocity control based on reinforcement learning for autonomous driving. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 117, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapan, M. Deep Reinforcement Learning Hands-on: Apply Modern RL Methods to Practical Problems of Chatbots, Robotics, Discrete Optimization, Web Automation, and More, 2nd ed.; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2020; Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?drect=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=2366458 (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Manchin, A.; Abbasnejad, E.; van den Hengel, A. Reinforcement Learning with Attention that Works: A Self-Supervised Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.0336. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, J.D. Radio Astronomy, 2nd ed.; Cygnus-Quasar Books: Powell, OH, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Baars, J.W.M. The Paraboloidal Reflector Antenna in Radio Astronomy and Communication: Theory and Practice; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Imbriale, W.A.; Yuen, J.H. Large Antennas of the Deep Space Network; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Price-Whelan, A.M.; Lim, P.L.; Earl, N.; Starkman, N.; Bradley, L.; Shupe, D.L.; Patil, A.A.; Corrales, L.; Brasseur, C.E.; Nöthe, M.; et al. The Astropy Project: Sustaining and growing a community-oriented open-source project and the latest major release (v5. 0) of the core package. Astrophys. J. 2022, 935, 167. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| RF Tuning Range | 70 MHz–6.0 GHz |

| Instantaneous Bandwidth | Up to 56 MHz |

| ADC/DAC Resolution | 12-bit |

| Maximum Sample Rate | 61.44 MS/s (Tx and Rx) |

| Rx Noise Figure | ~2.5 dB (typical, front-end dependent) |

| Rx Gain Control | Manual or Automatic Gain Control (AGC) |

| Tx Output Power | Programmable, up to +7 dBm |

| Digital Interface | High-speed LVDS to Zynq SoC (ZedBoard) |

| Ethernet Streaming | Configurable via FPGA logic and embedded Linux |

| Clocking | Internal oscillator or external 10 MHz reference |

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| System | X–Y, Cassegrain reflector, beam-waveguide antenna |

| Driving system | Digital electric servo with position forward control system error 5% |

| Primary axis | 1.5 kW 1500 rpm 8.3 N-m, 1:30,000 gearing ratio |

| Secondary axis | 1.5 kW 1500 rpm 8.3 N-m, 1:59,400 gearing ratio |

| Primary axis speed | 0.30 deg/s |

| Secondary axis speed | 0.15 deg/s |

| Position measuring error | 0.1% |

| Dish aperture | 10 m |

| Antenna beamwidth Operational frequency range | 2 degrees. 1–3 GHz. and 10.7–12.75 GHz. |

| Paremeter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| lr | 5.5 × 10−5 | Initial learning rate. |

| lr_min | 2.97 × 10−8 | Minimum learning rate. |

| batch_size | 256 | Minibatch size used to update the network |

| n_steps | 2048 | the number of steps to run for each environment per update |

| γ | 0.89 | Discounted factor for the future reward used for update |

| gae_lambda | 0.95 | Factor for trade-off of bias vs. variance for Generalized Advantage Estimator |

| Clip_range | 0.66 | PPO Clipping parameter |

| ent_coef | 0.0 | Entropy coefficient for the loss calculation |

| vf_coef | 0.5 | Value function coefficient for the loss calculation |

| net_arch_pi | [256,256,256,256] | Actor network size |

| net_arch_vf | [256,256,256,256] | Critic network size |

| activation_fn | tanh | Activation function for MPL. |

| Paremeter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| SNR_acc | 0.95 | Accuracy of SNR measuring |

| Pointing_error | 0.01 | Pointing error of position control system |

| NS_Speed | 0.1 | Maximum speed in primary axis in degree/s. |

| EW_Speed | 0.1 | Maximum speed in secondary axis in degree/s. |

| Moving_period | 10 | Moving period in second for each step. |

| Measuring_period | 4 | Measuring SNR period in second for each step. |

| Time_zone | 7 | Time zone of radio telescope location. |

| Observation_lat | 13.7308° | Latitude of radio telescope location. |

| Observation_lng | 100.7874° | Longitude of radio telescope location. |

| SNR_acc | 0.95 | Accuracy of SNR measuring |

| Pointing_error | 0.01 | Pointing error of position control system |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sahavisit, T.; Laon, P.; Pourbunthidkul, S.; Wichittrakarn, P.; Phasukkit, P.; Houngkamhang, N. Reinforcement Learning-Driven Framework for High-Precision Target Tracking in Radio Astronomy. Galaxies 2025, 13, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060124

Sahavisit T, Laon P, Pourbunthidkul S, Wichittrakarn P, Phasukkit P, Houngkamhang N. Reinforcement Learning-Driven Framework for High-Precision Target Tracking in Radio Astronomy. Galaxies. 2025; 13(6):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060124

Chicago/Turabian StyleSahavisit, Tanawit, Popphon Laon, Supavee Pourbunthidkul, Pattharin Wichittrakarn, Pattarapong Phasukkit, and Nongluck Houngkamhang. 2025. "Reinforcement Learning-Driven Framework for High-Precision Target Tracking in Radio Astronomy" Galaxies 13, no. 6: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060124

APA StyleSahavisit, T., Laon, P., Pourbunthidkul, S., Wichittrakarn, P., Phasukkit, P., & Houngkamhang, N. (2025). Reinforcement Learning-Driven Framework for High-Precision Target Tracking in Radio Astronomy. Galaxies, 13(6), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060124