Artificial Intelligence in Adult Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery: Real-World Deployments and Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search Strategy and Study Selection

Definition of Real-World Deployment and Evidence Maturity

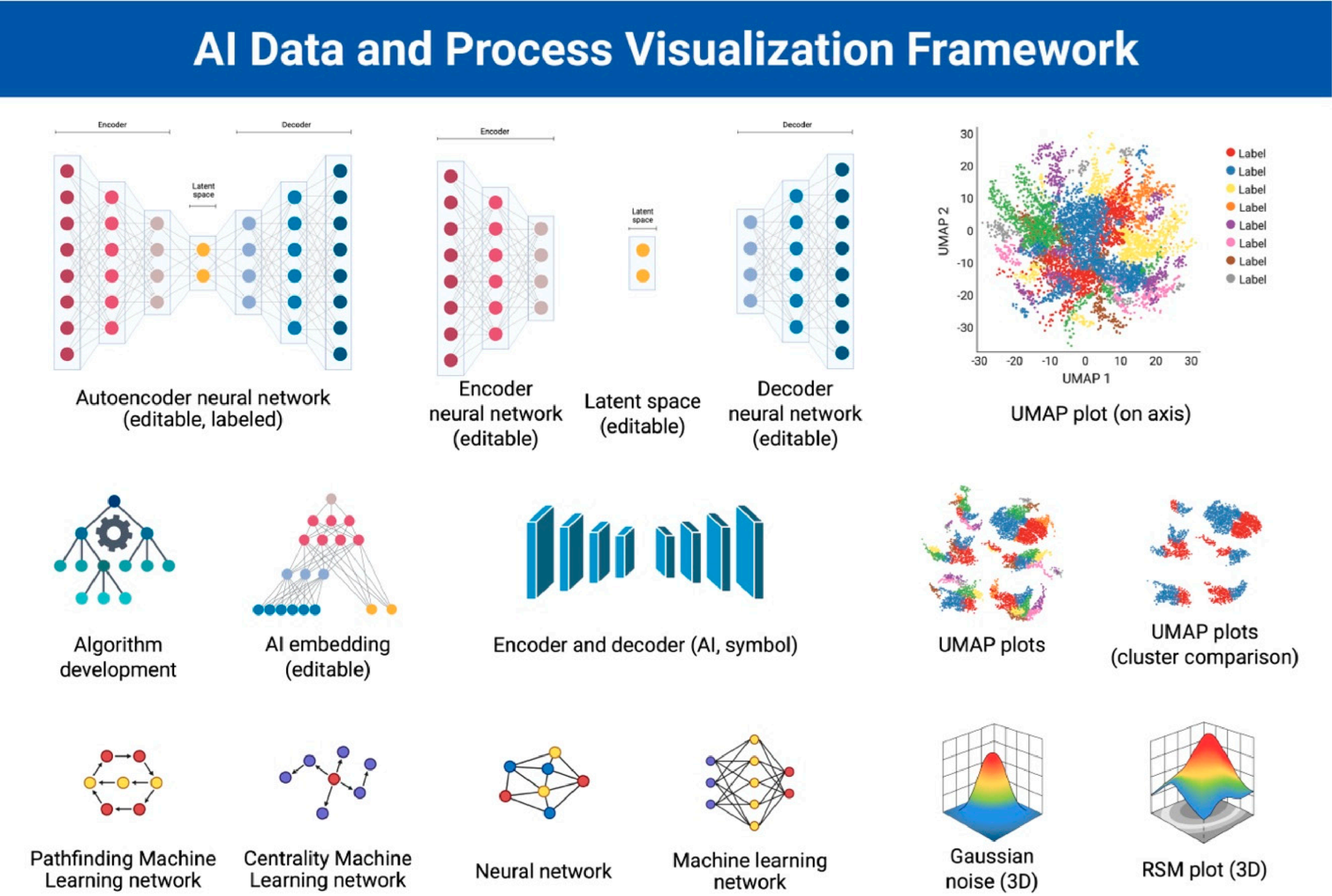

3. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) as the Basis for AI Models

3.1. Conceptual Foundations of Clinical AI

3.2. Core AI Architectures Used in Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery

4. AI in Preoperative Diagnostics and Risk Stratification

4.1. Enhanced Imaging Interpretation

4.2. Personalized Risk Prediction

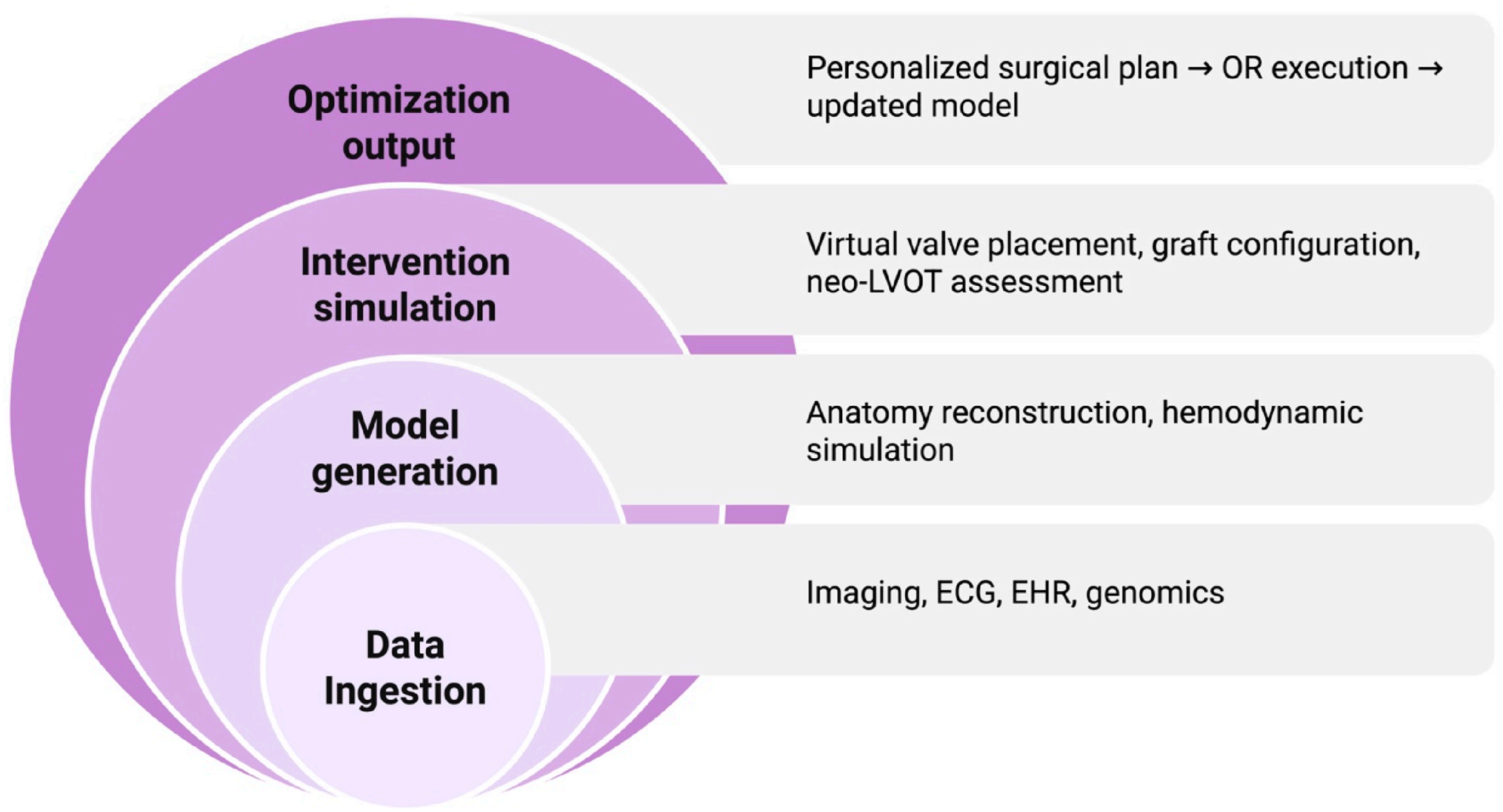

4.3. Surgical Planning and Virtual Simulation

4.4. Comparative Performance of AI, Traditional Risk Models, and Clinician Assessment

5. Intraoperative AI Assistance and Robotic Surgery

5.1. Robotics and Automation

5.2. AI-Enhanced Hemodynamic Management

5.3. Intraoperative Computer Vision

5.4. AI in Structural Heart Surgery

5.5. AI in Aortic Surgery

5.6. Digital and Hybrid Operating Room Ecosystems

5.7. Cost-Effectiveness of AI Adoption in Cardiac Surgery

5.8. Empirically Demonstrated Economic Impact in Cardiac Surgery

6. Postoperative AI Monitoring and ICU Decision Support

6.1. Predicting Postoperative Complications

6.2. Early Warning Systems and Real-Time Deterioration Predictions

6.3. AI in ICU Hemodynamic and Perfusion Management

6.4. Computer Vision for Postoperative Surveillance

- Patient agitation or delirium

- Line dislodgement risk

- Falls, unassisted bed exits

- Chest-tube output saturation patterns

- Early signs of tamponade such as increased respiratory effort or body-position changes

6.5. AI for Postoperative Workflow Optimization and Discharge Planning

7. Ethical, Regulatory, and Data-Governance Challenges in Cardiac AI

7.1. Transparency, Explainability, and Clinical Trust

7.2. Bias, Fairness, and Equity in Model Performance

7.3. Data Privacy, Security, and Consent

7.4. Regulatory Pathways for AI in Cardiac Surgery

7.5. Liability and Accountability

7.6. Data Drift, Model Decay, and Revalidation

8. Limitations of Current Evidence

8.1. Methodological, Data, and Implementation Limitations of Cardiac Surgical AI

8.2. Mixed and Negative Experiences with Real-World AI Deployment

9. Future Directions in Cardiac Surgical Artificial Intelligence

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nashef, S.A.; Roques, F.; Sharples, L.D.; Nilsson, J.; Smith, C.; Goldstone, A.R.; Lockowandt, U. EuroSCORE II. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2012, 41, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iribarne, A.; Zwischenberger, B.; Mehaffey, J.H.; Kaneko, T.; von Ballmoos, M.C.W.; Jacobs, J.P.; Krohn, C.; Habib, R.H.; Parsons, N.; Badhwar, V.; et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database: 2024 Update on National Trends and Outcomes. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2025, 119, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.H.; Chan, M.K.; Narayanan, D.; Staudenmayer, K.; Nassar, A.; Forrester, J.D.; Knowlton, L.M.; Hameed, S.M. Augmenting decision making in acute care surgery: A systematic review of machine learning–driven risk prediction models. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, V.M.; Goldsmith, M.P.; Shi, L.; Simpao, A.F.; Gálvez, J.A.; Naim, M.Y.; Nadkarni, V.; Gaynor, J.W.; Tsui, F. Early prediction of clinical deterioration using data-driven machine-learning modeling of electronic health records. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 164, 211–222.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, D.A.; Rosman, G.; Rus, D.; Meireles, O.R.M. Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: Promises and Perils. Ann. Surg. 2018, 268, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimabukuro, D.W.; Barton, C.W.; Feldman, M.D.; Mataraso, S.J.; Das, R. Effect of a machine learning-based severe sepsis prediction system on patient outcomes. Crit. Care. Med. 2017, 45, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, R.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Huang, S.-H.; Cheng, M.-H.; Yang, C.-T. Decision-making efficiency with aided information: The impact of automation reliability and task difficulty. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2025, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.N.; Rosenberg, L.; Willcox, G.; Baltaxe, D.; Lyons, M.; Irvin, J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Amrhein, T.; Gupta, R.; Halabi, S.; et al. Human–machine partnership with artificial intelligence for chest radiograph diagnosis. npj Digit. Med. 2019, 2, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, D.; Stryker, C. What is Loss Function? IBM. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/loss-function (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Bergmann, D.; Stryker, C. What is Backpropagation? IBM. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/backpropagation (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Brault, D. What Are the Different Types of AI Models? Mendix. Available online: https://www.mendix.com/blog/what-are-the-different-types-of-ai-models/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Çelik, Ö. A Research on Machine Learning Methods and Its Applications. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 2018, 1, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murel, J.; Kavlakoglu, E. What is Reinforcement Learning? IBM. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/reinforcement-learning (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- AlSaad, R.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Boughorbel, S.; Ahmed, A.; Renault, M.-A.; Damseh, R.; Sheikh, J. Multimodal Large Language Models in Health Care: Applications, Challenges, and Future Outlook. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e59505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Z.I.; Friedman, P.A.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Ladewig, D.J.; Satam, G.; Pellikka, P.A.; Munger, T.M.; Asirvatham, S.J.; Scott, C.G.; et al. Age and Sex Estimation Using Artificial Intelligence from Standard 12-Lead ECGs. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2019, 12, e007284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedinsewo, D.; Carter, R.E.; Attia, Z.; Johnson, P.; Kashou, A.H.; Dugan, J.L.; Albus, M.; Sheele, J.M.; Bellolio, F.; Friedman, P.A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled ECG Algorithm to Identify Patients with Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction Presenting to the Emergency Department with Dyspnea. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, e008437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcioglu, O.; Ozgocmen, C.; Ozsahin, D.U.; Yagdi, T. The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in the Prediction of Right Heart Failure after Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weberling, L.D.; Ochs, A.; Benovoy, M.; Siepen, F.A.D.; Salatzki, J.; Giannitsis, E.; Duan, C.; Maresca, K.; Zhang, Y.; Möller, J.; et al. Machine Learning to Automatically Differentiate Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Cardiac Light Chain, and Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis: A Multicenter CMR Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 18, e017761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, W.-Y.; Siontis, K.C.; Attia, Z.I.; Carter, R.E.; Kapa, S.; Ommen, S.R.; Demuth, S.J.; Ackerman, M.J.; Gersh, B.J.; Arruda-Olson, A.M.; et al. Detection of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Using a Convolutional Neural Network-Enabled Electrocardiogram. JACC 2020, 75, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruka, V.; Rad, A.A.; Ponniah, H.S.; Francis, J.; Vardanyan, R.; Tasoudis, P.; Magouliotis, D.E.; Lazopoulos, G.L.; Salmasi, M.Y.; Athanasiou, T. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in cardiac transplantation: A systematic review. Artif. Organs 2022, 46, 1741–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyaga-Rendon, R.Y.; Acharya, D.; Jani, M.; Lee, S.; Trachtenberg, B.; Manandhar-Shrestha, N.; Leacche, M.; Jovinge, S. Predicting Survival of End-Stage Heart Failure Patients Receiving HeartMate-3: Comparing Machine Learning Methods. Asaio J. 2023, 70, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allehyani, B.; Savo, M.T.; Khwaji, A.; Al Kholaif, N.; Galzerano, D.; Al Buraiki, J.; Alamro, B.; Al Sergani, H.; Di Salvo, G.; Cozac, D.A.; et al. Machine learning approach to predict 1-year mortality after heart transplantation: A single-centre study. Eur. Heart J.-Imaging Methods Pract. 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetto, U.; Dimagli, A.; Sinha, S.; Cocomello, L.; Gibbison, B.; Caputo, M.; Gaunt, T.; Lyon, M.; Holmes, C.; Angelini, G.D. Machine learning improves mortality risk prediction after cardiac surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 163, 2075–2087.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gala, D.; Behl, H.; Shah, M.; Makaryus, A.N. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Improving Patient Outcomes and Future of Healthcare Delivery in Cardiology: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Healthcare 2024, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illi, J.; Bernhard, B.; Nguyen, C.; Pilgrim, T.; Praz, F.; Gloeckler, M.; Windecker, S.; Haeberlin, A.; Gräni, C. Translating Imaging Into 3D Printed Cardiovascular Phantoms. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2022, 7, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, I.; Gomez-Ciriza, G.; Hussain, T.; Suarez-Mejias, C.; Velasco-Forte, M.N.; Byrne, N.; Ordoñez, A.; Gonzalez-Calle, A.; Anderson, D.; Hazekamp, M.G.; et al. Three-dimensional printed cardiac models for surgical planning in complex congenital heart disease. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 149, 699–706. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Liang, Z.; Du, R.; Song, T. High-fidelity, personalized cardiac modeling via AI-driven 3D reconstruction and embedded silicone rubber printing. Exp. Biol. Med. 2025, 250, 10756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujiie, H.; Yamaguchi, A.; Gregor, A.; Chan, H.; Kato, T.; Hida, Y.; Kaga, K.; Wakasa, S.; Eitel, C.; Clapp, T.R.; et al. Developing a virtual reality simulation system for preoperative planning of thoracoscopic thoracic surgery. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, O.; Dubey, G.; Benkabbou, A.; Majbar, M.A.; Souadka, A. Comprehensive overview of artificial intelligence in surgery: A systematic review and perspectives. Pflügers Arch.-Eur. J. Physiol. 2025, 477, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abjigitova, D.; Sadeghi, A.H.; Peek, J.J.; Bekkers, J.A.; Bogers, A.J.J.C.; Mahtab, E.A.F. Virtual Reality in the Preoperative Planning of Adult Aortic Surgery: A Feasibility Study. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, A.A.; Vardanyan, R.; Lopuszko, A.; Alt, C.; Stoffels, I.; Schmack, B.; Ruhparwar, A.; Zhigalov, K.; Zubarevich, A.; Weymann, A. Virtual and Augmented Reality in Cardiac Surgery. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 37, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye, W.M.M.; Kiraly, L.; Kumar, S.S.; Kasivishvanaath, A.; Gao, Y.; Kofidis, T. Mixed Reality (Holography)-Guided Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery—A Novel Comparative Feasibility Study. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponzoni, M.; Bertelli, F.; Yoo, S.-J.; Peel, B.; Seatle, H.; Honjo, O.; Haller, C.; Barron, D.J.; Seed, M.; Lam, C.Z.; et al. Mixed reality for preoperative planning and intraoperative assistance of surgical correction of complex congenital heart defects. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2025, 170, 327–335.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cersosimo, A.; Zito, E.; Pierucci, N.; Matteucci, A.; La Fazia, V.M. A Talk with ChatGPT: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Shaping the Future of Cardiology and Electrophysiology. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeßler, B.; Götz, M.; Antoniades, C.; Heidenreich, J.F.; Leiner, T.; Beer, M. Artificial intelligence in coronary computed tomography angiography: Demands and solutions from a clinical perspective. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1120361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shademan, A.; Decker, R.S.; Opfermann, J.D.; Leonard, S.; Krieger, A.; Kim, P.C.W. Supervised autonomous robotic soft tissue surgery. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 337ra64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano, J.C.R.; Ruiz, N.I.; Burbano, G.A.R.; Inca, J.S.G.; Lezama, C.A.A.; González, M.S. Robot-Assisted Surgery: Current Applications and Future Trends in General Surgery. Cureus 2025, 17, e82318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarillo, D.B.; Krummel, T.M.; Salisbury, J. Robotic technology in surgery: Past, present, and future. Am. J. Surg. 2004, 188, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassahun, Y.; Yu, B.; Tibebu, A.T.; Stoyanov, D.; Giannarou, S.; Metzen, J.H.; Vander Poorten, E. Surgical robotics beyond enhanced dexterity: A survey of machine learning techniques and intelligent features. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2016, 11, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedula, S.S.; Gyulai, Z.; Ishii, M.; Hager, G.D. Surgical data science: The new knowledge domain. JAMA Surg. 2017, 152, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier-Hein, L.; Vedula, S.S.; Speidel, S.; Navab, N.; Kikinis, R.; Park, A.; Eisenmann, M.; Feussner, H.; Forestier, G.; Giannarou, S.; et al. Surgical data science for next-generation interventions. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, L.; Piazzolla, P.; Porpiglia, F.; Vezzetti, E. Real-time deep learning semantic segmentation during intra-operative surgery for 3D augmented reality assistance. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2021, 16, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizmic, A.; Mitra, A.T.; Preukschas, A.A.; Kemper, M.; Melling, N.T.; Mann, O.; Markar, S.; Hackert, T.; Nickel, F. Artificial intelligence for intraoperative video analysis in robotic-assisted esophagectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2025, 39, 2774–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, R.A.; Duffourc, M.D.J.; Gerke, S.D.-J.U. The AI-enhanced surgeon—Integrating black-box artificial intelligence in the operating room. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 2823–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Amsterdam, B.; Funke, I.; Edwards, E.; Speidel, S.; Collins, J.; Sridhar, A.; Kelly, J.; Clarkson, M.J.; Stoyanov, D. Gesture Recognition in Robotic Surgery with Multimodal Attention. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2022, 41, 1677–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftikhar, M.M.; Saqib, M.M.; Zareen, M.M.; Mumtaz, H.M. Artificial intelligence: Revolutionizing robotic surgery: Review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 5401–5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Kim, D.; Kim, D.W.; Baek, S.; Lee, H.-C.; Kim, Y.; Ahn, H.J. Prediction of intraoperative hypotension using deep learning models based on non-invasive monitoring devices. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2024, 38, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habicher, M.; Kleymann, R.; Shakkour, K.; Holstein, N.; Koch, C.; Markmann, M.; Schneck, E.; Sander, M. AI-supported non-invasive measurement for intraoperative hypotension reduction in major Orthopedic and trauma surgery—Study protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials 2025, 26, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.S.; Stout, D.M.; Fletcher, R.; Barksdale, A.; Parikshak, M.; Johns, C.; Gerdisch, M. Advanced artificial intelligence–guided hemodynamic management within cardiac enhanced recovery after surgery pathways: A multi-institution review. JTCVS Open 2023, 16, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, K.; Shimada, T.; Yang, D.; Khanna, S.; Cywinski, J.B.; Irefin, S.A.; Ayad, S.; Turan, A.; Ruetzler, K.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Hypotension Prediction Index for Prevention of Hypotension during Moderate- to High-risk Noncardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology 2020, 133, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michard, F.; Mulder, M.P.; Gonzalez, F.; Sanfilippo, F. AI for the hemodynamic assessment of critically ill and surgical patients: Focus on clinical applications. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2025, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Ogara, P.; Borges, P.; Rance, G.; Srey, R.; Harari, R.; Mendu, S.; et al. AI-Based Decision Support for Perfusionists during Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Hamlyn Symp. Med. Robot. 2025, 2025, 171–172. [Google Scholar]

- Coeckelenbergh, S.; Boelefahr, S.; Alexander, B.; Perrin, L.; Rinehart, J.; Joosten, A.; Barvais, L. Closed-loop anesthesia: Foundations and applications in contemporary perioperative medicine. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2024, 38, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bequette, B.W. Fault Detection and Safety in Closed-Loop Artificial Pancreas Systems. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2014, 8, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Han, T.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Hou, G.; Sun, L.; Jiang, G.; Yang, F.; Wang, J.; Deng, K.; et al. Detection of blood stains using computer vision-based algorithms and their association with postoperative outcomes in thoracoscopic lobectomies. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2022, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K.; Kitaguchi, D.; Takenaka, S.; Tanaka, A.; Ryu, K.; Takeshita, N.; Kinugasa, Y.; Ito, M. Automated surgical skill assessment in colorectal surgery using a deep learning-based surgical phase recognition model. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 6347–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peul, R.C.; Kharbanda, R.K.; Koning, S.; Kruiswijk, M.W.; Tange, F.P.; Hoven, P.v.D.; Vahrmeijer, A.L.; Klautz, R.J.; Hamming, J.F.; Hjortnaes, J.; et al. Intraoperative assessment of myocardial perfusion using near-infrared fluorescence and indocyanine green: A literature review. JTCVS Tech. 2025, 30, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yannakula, V.K.; Alluri, A.A.; Samuel, D.; A Popoola, S.; Barake, B.A.; Alabbasi, A.; Ahmed, A.S.; Bandy, D.A.C.; Jesi, N.J. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Providing Real-Time Guidance During Interventional Cardiology Procedures: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e83464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Jang, J.-H.; Kang, S.; Han, G.I.; Yoo, A.-H.; Jo, Y.-Y.; Son, J.M.; Kwon, J.-M.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.S.; et al. Transparent and Robust Artificial Intelligence-Driven Electrocardiogram Model for Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toggweiler, S.; von Ballmoos, M.C.W.; Moccetti, F.; Douverny, A.; Wolfrum, M.; Imamoglu, Z.; Mohler, A.; Gülan, U.; Kim, W.-K. A fully automated artificial intelligence-driven software for planning of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Cardiovasc. Revascularization Med. 2024, 65, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Niu, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Song, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, D.; et al. Development and validation of a deep learning-based fully automated algorithm for pre-TAVR CT assessment of the aortic valvular complex and detection of anatomical risk factors: A retrospective, multicentre study. eBioMedicine 2023, 96, 104794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.J.; Elmariah, S.; Kaneko, T.; Daniels, D.V.; Makkar, R.R.; Chikermane, S.G.; Thompson, C.; Benuzillo, J.; Clancy, S.; Pawlikowski, A.; et al. Machine Learning Identification of Modifiable Predictors of Patient Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, S.; Mousavi, A.; Kazemian, S.; Armani, S.; Maleki, S.; Fallahtafti, P.; Arashlow, F.T.; Daryabari, Y.; Naderian, M.; Alkhouli, M.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Risk Stratification and Outcome Prediction for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.D.; Eng, M.; Greenbaum, A.; Myers, E.; Forbes, M.; Pantelic, M.; Song, T.; Nelson, C.; Divine, G.; Taylor, A.; et al. Predicting LVOT Obstruction After TMVR. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, 1349–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Ranard, L.; Vahl, T.; Khalique, O. Advanced Computer Simulation Based on Cardiac Imaging in Planning of Structural Heart Disease Interventions. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, H.; Mahmood, F.; Sehgal, S.; Belani, K.; Sharkey, A.; Chaudhary, O.; Baribeau, Y.; Matyal, R.; Khabbaz, K.R. Artificial Intelligence for Dynamic Echocardiographic Tricuspid Valve Analysis: A New Tool in Echocardiography. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2020, 34, 2703–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Suppah, M.; Niazi, O.; Pershad, A. Left atrial appendage occlusion optimized with artificial intelligence-guided CT pre-planning and intra-procedural intracardiac echocardiographic guidance. Cardiovasc. Revascularization Med. 2025, 80, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inomata, S.; Yoshimura, T.; Tang, M.; Ichikawa, S.; Sugimori, H. Automatic Aortic Valve Extraction Using Deep Learning with Contrast-Enhanced Cardiac CT Images. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhao, L.; Yan, J.; Zhang, H.; Lin, S.; Yin, L.; Peng, C.; Ma, X.; Xie, G.; Sun, L. A deep learning algorithm for the detection of aortic dissection on non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography via the identification and segmentation of the true and false lumens of the aorta. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2024, 14, 7365–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, E.M.K.; Chen, S.; Ng, K.H.L.; Wong, R.H.L. Artificial intelligence-powered solutions for automated aortic diameter measurement in computed tomography: A narrative review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2024, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Eisenberg, N.; Beaton, D.; Lee, D.S.; Aljabri, B.; Al-Omran, L.; Wijeysundera, D.N.; Rotstein, O.D.; Lindsay, T.F.; de Mestral, C.; et al. Using Machine Learning to Predict Outcomes Following Thoracic and Complex Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e039221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, P.; An, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.-X. AI-powered automated model construction for patient-specific CFD simulations of aortic flows. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadw2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaka, A.; Mustafiz, C.; Mutahar, D.; Sinhal, S.; Gorcilov, J.; Muston, B.; Evans, S.; Gupta, A.; Stretton, B.; Kovoor, J.; et al. Machine-learning versus traditional methods for prediction of all-cause mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2025, 12, e002779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.C.; Mofidi, R. Natural Language Processing framework for identifying abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs using unstructured electronic health records. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wah, J.N.K. The rise of robotics and AI-assisted surgery in modern healthcare. J. Robot. Surg. 2025, 19, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Wang, D.; Chen, X. Advances in the Application of Three-Dimensional Reconstruction in Thoracic Surgery: A Comprehensive Review. Thorac. Cancer 2025, 16, e70159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.M.; Rajesh, A.; Asaad, M.; Nelson, J.A.; Coert, J.H.; Mehrara, B.J.; Butler, C.E. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Prediction of Surgical Complications: Current State, Applications, and Implications. Am. Surg. 2022, 89, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulague, R.M.; Beloy, F.J.; Medina, J.R.; Mortalla, E.D.; Cartojano, T.D.; Macapagal, S.; Kpodonu, J. Artificial intelligence in cardiac surgery: A systematic review. World J. Surg. 2024, 48, 2073–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiachristas, A.; Chan, K.; Wahome, E.; Ben Kearns, B.; Patel, P.; Lyasheva, M.; Syed, N.; Fry, S.; Halborg, T.; West, H.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of a novel AI technology to quantify coronary inflammation and cardiovascular risk in patients undergoing routine coronary computed tomography angiography. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2024, 11, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Gerich, H.; Helenius, M.; Hörhammer, I.; Moen, H.; Peltonen, L.-M. Scoping review on the economic aspects of machine learning applications in healthcare. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 205, 106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenig, N.; Echeverria, J.M.; Vives, A.M. Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: A Systematic Review of Use and Validation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lex, J.R.; Abbas, A.; Mosseri, J.; Toor, J.S.; Simone, M.; Ravi, B.; Whyne, C.; Khalil, E.B. Using Machine Learning to Predict-Then-Optimize Elective Orthopedic Surgery Scheduling to Improve Operating Room Utilization: Retrospective Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2025, 13, e70857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Farmer, P.E.; Tully, J.L.; Waterman, R.S.; Gabriel, R.A. Forecasting Surgical Bed Utilization: Architectural Design of a Machine Learning Pipeline Incorporating Predicted Length of Stay and Surgical Volume. J. Med. Syst. 2025, 49, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, P.; Groenhoff, L.; Ostillio, E.; Coraducci, F.; Secchi, F.; Carriero, A.; Colarieti, A.; Stecco, A. Advancements in Cardiac CT Imaging: The Era of Artificial Intelligence. Echocardiography 2024, 41, e70042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.T.; Zeng, Z.; Chatterjee, S.; Wall, M.J.; Moon, M.R.; Coselli, J.S.; Rosengart, T.K.; Li, M.; Ghanta, R.K. Machine learning for dynamic and early prediction of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 166, e551–e564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomašev, N.; Glorot, X.; Rae, J.W.; Zielinski, M.; Askham, H.; Saraiva, A.; Mottram, A.; Meyer, C.; Ravuri, S.; Protsyuk, I.; et al. A clinically applicable approach to continuous AKI prediction using machine learning. Nature 2019, 572, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanidou, L.; Rovas, G.; Mohammadi, R.; Anagnostopoulos, S.; Orhon, C.Ç.; Stergiopulos, N. Machine learning-enabled estimation of cardiac output from peripheral waveforms is independent of blood pressure measurement location in an in silico population. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Huang, M.; Yao, Y.; Ming, Y.; Yan, M.; Yu, Y.; Yu, L. Machine Learning Models of Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation Prediction After Cardiac Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2022, 37, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-H.; Chung, H.-Y.; Jian, M.-J.; Chang, C.-K.; Lin, H.-H.; Yen, C.-T.; Tang, S.-H.; Pan, P.-C.; Perng, C.-L.; Chang, F.-Y.; et al. AI-Driven Innovations for Early Sepsis Detection by Combining Predictive Accuracy with Blood Count Analysis in an Emergency Setting: Retrospective Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e56155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Kotula, C.; Martin, J.; A Carey, K.; Edelson, D.P.; Dligach, D.; Mayampurath, A.; Afshar, M.; Churpek, M.M. Comparison of Multimodal Deep Learning Approaches for Predicting Clinical Deterioration in Ward Patients: Observational Cohort Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e75340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hames, D.L.; Sleeper, L.A.S.; Bullock, K.J.R.; Feins, E.N.; Mills, K.I.; Laussen, P.C.M.; Salvin, J.W. Associations with Extubation Failure and Predictive Value of Risk Analytics Algorithms with Extubation Readiness Tests Following Congenital Cardiac Surgery. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 23, e208–e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Xie, G.; Feng, M.; See, K.C. Reinforcement Learning to Optimize Ventilator Settings for Patients on Invasive Mechanical Ventilation: Retrospective Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e44494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripollés-Melchor, J.; Carrasco-Sánchez, L.; Tomé-Roca, J.L.; Aldecoa, C.; Zorrilla-Vaca, A.; Lorente-Olazábal, J.V.; Colomina, M.J.; Pérez, A.; Jiménez-López, J.I.; Navarro-Pérez, R.; et al. Hypotension prediction index guided goal-directed therapy to reduce postoperative acute kidney injury during major abdominal surgery: Study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial. Trials 2024, 25, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, R.D.; Zenati, M.A.; Rance, G.; Srey, R.; Arney, D.; Chen, L.; Paleja, R.; Kennedy-Metz, L.R.; Gombolay, M. Using machine learning to predict perfusionists’ critical decision-making during cardiac surgery. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. Imaging Vis. 2021, 10, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, J.; Pattberg, K.; Nensa, F.; Kuhlmann, H.; Brenner, T.; Schmidt, K.; Hosch, R.; Espeter, F. A proof of concept for microcirculation monitoring using machine learning based hyperspectral imaging in critically ill patients: A monocentric observational study. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, R.; Nalaie, K.; Ayala, I.; Behaine, J.J.M.; Garcia-Mendez, J.P.; Friesen, H.; Leistikow, K.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Jayaraman, A.; Franco, P.M.; et al. Harnessing the Power of Technology to Transform Delirium Severity Measurement in the Intensive Care Unit: Protocol for a Prospective Cohort Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2025, 14, e62912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.; Ribeiro, B.; Sousa, I.; Santos, J.; Guede-Fernández, F.; Dias, P.; Carreiro, A.V.; Gamboa, H.; Coelho, P.; Fragata, J.; et al. Predicting post-discharge complications in cardiothoracic surgery: A clinical decision support system to optimize remote patient monitoring resources. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 182, 105307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-Y.; Son, Y.-J. Machine learning–based 30-day readmission prediction models for patients with heart failure: A systematic review. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2024, 23, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, H.-W.; Chu, Y.-C.; Tsai, H.-C.; Lin, C.-L.; Chen, C.-Y.; Ma, M.H.-M. Efficacy of Remote Health Monitoring in Reducing Hospital Readmissions Among High-Risk Postdischarge Patients: Prospective Cohort Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e53455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, M.; Oakden-Rayner, L.; Beam, A.L. The false hope of current approaches to explainable artificial intelligence in health care. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e745–e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xie, W.; Liao, B.; Hu, C.; Qin, L.; Yang, Z.; Xiong, H.; Lyu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, A. Interpretability of Clinical Decision Support Systems Based on Artificial Intelligence from Technological and Medical Perspective: A Systematic Review. J. Healthc. Eng. 2023, 2023, 9919269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straw, I.; Rees, G.; Nachev, P. Sex-Based Performance Disparities in Machine Learning Algorithms for Cardiac Disease Prediction: Exploratory Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e46936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanzadeh, F.; Josephson, C.B.; Waters, G.; Adedinsewo, D.; Azizi, Z.; White, J.A. Bias recognition and mitigation strategies in artificial intelligence healthcare applications. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Kaissis, G.A.; Makowski, M.R.; Rückert, D.; Braren, R.F. Secure and privacy-preserving federated learning in medical imaging. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, S.H.; van Thiel, G.J.; Mostert, M.; van Delden, J.J. Dynamic consent, communication and return of results in large-scale health data reuse: Survey of public preferences. Digit. Health 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to AI/ML-Based SaMD; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021.

- Steerling, E.; Siira, E.; Nilsen, P.; Svedberg, P.; Nygren, J. Implementing AI in healthcare—The relevance of trust: A scoping review. Front. Health Serv. 2023, 3, 1211150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habli, I.; Lawton, T.; Porter, Z. Artificial intelligence in health care: Accountability and safety. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kulkarni, P.; Mahadevappa, M.; Chilakamarri, S. The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence in Cardiology: Current and Future Applications. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2022, 18, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otokiti, A.U.; Ozoude, M.M.; Williams, K.S.; A Sadiq-Onilenla, R.; Ojo, S.A.; Wasarme, L.B.; Walsh, S.; Edomwande, M. The Need to Prioritize Model-Updating Processes in Clinical Artificial Intelligence (AI) Models: Protocol for a Scoping Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e37685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, B.J.; Nguyen, H.M.; McWilliams, A.; Pallini, M.; Bovi, A.; Kuzma, A.; Kramer, J.; Chou, S.-H.; Hetherington, T.; Corn, P.; et al. A practical framework for appropriate implementation and review of artificial intelligence (FAIR-AI) in healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norori, N.; Hu, Q.; Aellen, F.M.; Faraci, F.D.; Tzovara, A. Addressing bias in big data and AI for health care: A call for open science. Patterns 2021, 2, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shung, D.L.; Sung, J.J.Y. Challenges of developing artificial intelligence-assisted tools for clinical medicine. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.; Shenoy, E.S. Machine Learning for Healthcare: On the Verge of a Major Shift in Healthcare Epidemiology. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 66, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, D.; Lim, M.; Lee, S. Challenges for Data Quality in the Clinical Data Life Cycle: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e60709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichosz, S.L. Enhancing Transparency and Reporting Standards in Diabetes Prediction Modeling: The Significance of the TRIPOD+AI 2024 Statement. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2024, 18, 989–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, B. Key concepts, common pitfalls, and best practices in artificial intelligence and machine learning: Focus on radiomics. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 28, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.D.; Archer, L.; I E Snell, K.; Ensor, J.; Dhiman, P.; Martin, G.P.; Bonnett, L.J.; Collins, G.S. Evaluation of clinical prediction models (part 2): How to undertake an external validation study. BMJ 2024, 384, e074820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayas, C.E.; Whorton, J.M.; Sexton, K.W.; Mabry, C.D.; Dowland, S.C.; Brochhausen, M. Development and validation of the early warning system scores ontology. J. Biomed. Semant. 2023, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzikou, M.; Latsou, D.; Apostolidis, G.; Billis, A.; Charisis, V.; Rigas, E.S.; Bamidis, P.D.; Hadjileontiadis, L. Economic Evaluation of Artificially Intelligent (AI) Diagnostic Systems: Cost Consequence Analysis of Clinician-Friendly Interpretable Computer-Aided Diagnosis (ICADX) Tested in Cardiology, Obstetrics, and Gastroenterology, from the HosmartAI Horizon 2020 Project. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, M.; Banerjee, O.; Abad, Z.S.H.; Krumholz, H.M.; Leskovec, J.; Topol, E.J.; Rajpurkar, P. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature 2023, 616, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, K.; Katsakiori, P.F.; Papadimitroulas, P.; Strigari, L.; Kagadis, G.C. Digital Twins’ Advancements and Applications in Healthcare, Towards Precision Medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekki, Y.M.; Luijten, G.; Hagert, E.; Belkhair, S.; Varghese, C.; Qadir, J.; Solaiman, B.; Bilal, M.; Dhanda, J.; Egger, J.; et al. Digital twins for the era of personalized surgery. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Raison, N.; Martinez, A.G.; Ourselin, S.; Montorsi, F.; Briganti, A.; Dasgupta, P. At the cutting edge: The potential of autonomous surgery and challenges faced. BMJ Surg. Interv. Health Technol. 2025, 7, e000338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.B.; Quintero-Peña, C.; Moise, A.C.; Lumsden, A.B.; Corr, S.J. From Data to Decision: A Comprehensive Review of Real-Time Analytics and Smart Technologies in the Surgical Suite. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc. J. 2025, 21, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, D.; Burke, C.; Madden, M.G.; Ullah, I. Automated assessment of simulated laparoscopic surgical skill performance using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingert, T.; Lee, C.; Cannesson, M. Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Closed Loop Devices—Anesthesia Delivery. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2021, 39, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaraman, P.; Desman, J.; Sabounchi, M.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Sakhuja, A. A Primer on Reinforcement Learning in Medicine for Clinicians. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Mimila, P.; Wang, J.; Huertas-Vazquez, A. Relevance of Multi-Omics Studies in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.H.U.; Pinaya, W.H.L.; Nachev, P.; Teo, J.T.; Ourselin, S.; Cardoso, M.J. Federated learning for medical imaging radiology. Br. J. Radiol. 2023, 96, 20220890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, S.; Senthilkumar, B. A privacy preserving machine learning framework for medical image analysis using quantized fully connected neural networks with TFHE based inference. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedula, S.S.; Hager, G.D. Surgical data science: The new knowledge domain. Innov. Surg. Sci. 2017, 2, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duci, M.; Bossi, A.; Uccheddu, F.; Fascetti-Leon, F. A roadmap of artificial intelligence applications in pediatric surgery: A comprehensive review of applications, challenges, and ethical considerations. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2025, 41, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, S.C.; Dasgupta, P.; Haram, M.; Hachach-Haram, N. Leveraging data science and AI to democratize global surgical expertise. BMJ Surg. Interv. Health Technol. 2024, 6, e000334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Perioperative Phase | AI Application | Clinical Purpose | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative Diagnostics | Deep-learning ECG analysis | Detect subclinical LV dysfunction; predict long-term survival and operative risk | AI-ECG for EF < 35%; AI-derived cardiac age |

| Automated CT/MRI segmentation | Rapid extraction of anatomy, calcification burden, chamber volumes | TAVR annulus sizing; aortic morphology modeling | |

| Echocardiographic video analysis | Predict RV failure, identify cardiomyopathies | Stanford LVAD RV-failure prediction model | |

| NLP extraction of risk variables | Automated identification of clinical features and comorbidities | EHR-driven early-warning systems | |

| Risk Stratification | Machine-learning mortality/morbidity prediction | Improve upon STS and EuroSCORE II performance | ANN models; gradient-boosted trees; XGBoost risk scores |

| Multimodal prognostic models | Integrate imaging, labs, ECG, and clinical notes for individualized risk | Foundation models using multimodal data | |

| Surgical Planning/Structural Heart | Virtual valve implantation & neo-LVOT simulation | Prevent LVOT obstruction; optimize TMVR | Deep-learning TMVR simulation tools |

| AI-driven TAVR planning | Valve sizing, PVL prediction, conduction disturbance risk | Automated CT analysis; ML-based sizing | |

| 3D printing + ML segmentation | Preoperative rehearsal and hazard identification | Minnesota 3D cardiac models | |

| Intraoperative Assistance | AI-guided hemodynamics (HPI) | Predict hypotension; optimize perfusion | HPI in cardiac ERAS pathways |

| Computer vision in live video | Detect bleeding, track instruments, identify tissue planes | Blood-pixel CV models; OR Black Box | |

| Intelligent robotic functions | Tremor filtering, tool tracking, semi-autonomous suturing | STAR robot; AI-augmented robotics | |

| Postoperative Care/ICU | Early-warning models | Predict AKI, LCOS, respiratory failure, delirium | eCART, AI AKI models, waveform analytics |

| Closed-loop physiologic control | Automated vasopressor, ventilation, temperature adjustments | Reinforcement-learning ventilator control | |

| Remote AI monitoring | -detected arrhythmias, effusions, hemodynamic instability post-discharge | AI-enabled wearables and home telemetry |

| Perioperative Phase | AI Application | Model Type | Study Design/Evidence Level | Sample Size | Performance Metrics | Clinical Outcome Impact | Comparator | Deployment Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | AI-enabled ECG for LV dysfunction | CNN | Retrospective, external validation | >40,000 | AUC ~0.85 | Prediction of future LV dysfunction | Cardiologist ECG interpretation | Retrospective |

| Preoperative | AI-ECG “cardiac age” | Deep learning | Retrospective cohort | 13,808 CABG pts | HR ↑ with age gap | Worse 5- and 10-yr survival | Chronologic age | Retrospective |

| Preoperative | Echo-based RV failure prediction (LVAD) | CNN | Multicenter retrospective | 941 | AUC 0.73 | Improved RV failure risk identification | Clinical scores; experts | Retrospective |

| Preoperative | ML mortality prediction | XGBoost/ANN | Registry-based retrospective | 4874 | AUC > STS | Improved mortality & morbidity prediction | STS risk calculator | Retrospective |

| Intraoperative | Hypotension Prediction Index (HPI) | ML waveform analysis | Prospective observational | >600 cardiac pts | Sens/Spec > 80% | ↓ ventilation time; improved stability | Standard MAP monitoring | Implemented |

| Intraoperative | Autonomous suturing (STAR) | CV + ML | Preclinical | N/A | Technical accuracy metrics | Superior suture consistency | Expert surgeons | Experimental |

| Intraoperative | OR Black Box motion analysis | CV + ML | Prospective observational | Hundreds | Error detection > 90% | Identification of unsafe motions | Human observation | Pilot deployment |

| Postoperative | AKI prediction | ML/RNN | Retrospective | 1000–10,000 | AUC 0.75–0.85 | Earlier AKI risk identification | Logistic regression | Retrospective |

| Postoperative | ICU early-warning systems | ML ensemble | Prospective & implemented | >50,000 | AUC ~0.80 | ↓ ICU transfers; ↓ mortality | Rule-based alerts | Implemented |

| Postoperative | Remote AI monitoring | ML | Prospective pilot | Hundreds | Detection accuracy reported | ↓ readmissions | Standard follow-up | Pilot |

| AI Modality | Core Capabilities | Clinical Contributions | Key Domains in Cardiac Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Pattern recognition; structured data modeling | Improved risk stratification; complication prediction | STS augmentation, mortality/morbidity models, AKI prediction |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Image, waveform, and time-series analysis | Automated imaging interpretation; physiologic signature detection | Echocardiography, MRI, AI-ECG, perfusion waveforms |

| Computer Vision (CV) | Real-time surgical video interpretation | Intraoperative bleeding quantification; skill assessment | OR Black Box, robotic guidance, structural interventions |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | Extraction of free-text clinical data | Automated registry development; continuous monitoring | Operative notes, radiology reports, EHR extraction |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Adaptive decision policies based on feedback | Closed-loop physiologic control; autonomous systems | Ventilation control, perfusion optimization |

| Foundation/Multimodal Models | Cross-domain integration of images, signals, genomics, and text | Holistic patient modeling; universal risk profiles | Digital twins, comprehensive perioperative prediction |

| Simulation & Digital Twins | Virtual physiological modeling | Preoperative rehearsal; device simulation | TMVR, aortic repair, TEVAR computational planning |

| Challenge Category | Description | Impact on Clinical Adoption | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality & Generalizability | Single-center, retrospective datasets; inconsistent variable definitions | Reduced external validity; model degradation | Variability in LCOS and vasoplegia definitions |

| Transparency & Explainability | Black-box models with limited interpretability | Clinician distrust; regulatory resistance | Lack of rationale for AI risk predictions |

| Bias & Fairness | Underrepresentation of minority groups, women, older adults | Performance disparities; potential harm | Differential calibration of models by race/sex |

| Workflow Integration | Poor interface design; alert fatigue; limited EHR integration | Failure to improve outcomes despite strong predictive performance | Early-warning systems with low response rates |

| Regulatory & Liability Issues | Unclear oversight for adaptive algorithms | Hesitancy to deploy AI in high-risk procedures | FDA SaMD change-control challenges |

| Model Drift & Maintenance | Changing patient populations, surgical techniques | Performance decline without retraining | Aortic and valve practice evolution |

| Economic & Resource Constraints | Cost of adoption, staff training, IT infrastructure | Slower implementation; inequitable access | Hybrid OR integration costs; cloud computing fees |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Magouliotis, D.E.; Sicouri, N.; Ramlawi, L.; Baudo, M.; Androutsopoulou, V.; Sicouri, S. Artificial Intelligence in Adult Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery: Real-World Deployments and Outcomes. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020069

Magouliotis DE, Sicouri N, Ramlawi L, Baudo M, Androutsopoulou V, Sicouri S. Artificial Intelligence in Adult Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery: Real-World Deployments and Outcomes. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(2):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020069

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagouliotis, Dimitrios E., Noah Sicouri, Laura Ramlawi, Massimo Baudo, Vasiliki Androutsopoulou, and Serge Sicouri. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence in Adult Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery: Real-World Deployments and Outcomes" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 2: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020069

APA StyleMagouliotis, D. E., Sicouri, N., Ramlawi, L., Baudo, M., Androutsopoulou, V., & Sicouri, S. (2026). Artificial Intelligence in Adult Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery: Real-World Deployments and Outcomes. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(2), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020069