Genetic Burden and APOE Methylation in a Korean Multi-Generational Alzheimer’s Disease Family: An Exploratory Multi-Omics Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

2.3. Genotyping Using Korean Chip v2.0

2.3.1. Korean Chip v2.0 Platform

2.3.2. Genotyping Procedure

2.3.3. Quality Control

- -

- Sample call rate ≥ 95%

- -

- SNP call rate ≥ 95%

- -

- Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) p-value > 1 × 10−6 (noted for reference; not applicable for family data)

- -

- Minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.01 in the Korean reference population

2.4. Candidate Gene Selection and Genetic Burden Score (GBS) Calculation

2.4.1. AD Candidate Gene Selection

2.4.2. Variant Extraction and Annotation

- Lead GWAS SNPs (n = 2 for APOE: rs429358, rs7412): SNPs directly reported as genome-wide significant (p < 5 × 10−8) in source publications.

- LD proxy variants (n = 318): SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.6 in 1000 Genomes Project East Asian populations: JPT + CHB) with genome-wide significant lead variants. Risk allele designation for LD proxies was inferred based on the LD phase with the lead SNP’s risk allele.

- Functional annotation filter: Among LD proxies, priority was given to variants with functional annotations in the Korean Chip v2.0 reference database (e.g., missense, regulatory, and eQTL effects).

2.4.3. Variant Quality Control for GBS Calculation

- -

- Biallelic SNPs only (multi-allelic variants excluded);

- -

- Clear risk allele designation from published GWAS;

- -

- Polymorphic within the family cohort (non-monomorphic sites);

- -

- No missing genotypes across all seven members.

2.4.4. GBS Calculation

2.4.5. Genetic Burden Score (GBS): Distinction from GWAS-Based Polygenic Risk Scores

- -

- Utilizes effect-size weights from large-scale GWAS (typically β coefficients or odds ratios);

- -

- Includes 50,000 to >1 million genome-wide variants;

- -

- Designed for population-level risk prediction;

- -

- Requires external validation in independent cohorts;

- -

- Output can be converted to disease probability or percentile rank;

- -

- Assumes weights transfer across populations (often problematic for non-European ancestries).

- -

- Uses simple unweighted allele counting (0, 1, or 2 risk alleles per SNP);

- -

- Focuses on 320 variants across six well-established AD candidate genes (318 from Korean Chip v2.0 array + 2 APOE ε-defining SNPs genotyped independently);

- -

- Designed for within-family relative comparison, not absolute prediction;

- -

- No external weights applied (inappropriate for single-family studies);

- -

- Output represents relative genetic burden within this family only;

- -

- Cannot be compared to population PRS values or converted to disease probabilities.

- Within-family comparison priority: Family studies aim to identify relative patterns among blood relatives sharing a genetic background, not to predict absolute disease risk. GBS is sufficient for comparing “high” vs. “low” burden siblings.

- Population weight transferability issues: GWAS-derived effect sizes come from European ancestry cohorts. Applying these weights to Korean families may introduce bias due to differences in allele frequencies, linkage disequilibrium patterns, and gene–environment interactions.

- Avoiding false precision: Using population-derived weights would imply prediction accuracy that cannot be validated in a single family. Unweighted GBS acknowledges the exploratory nature of the analysis.

- Biological interpretability: Equal weighting allows direct interpretation of gene-specific contributions without confounding from external population parameters.

- -

- Risk variants outside the six candidate genes (potentially 50+ additional GWAS loci);

- -

- Rare family-specific variants with large effects (not captured on arrays);

- -

- Structural variants and copy number variations;

- -

- Protective variants that may explain resilience in high-GBS individuals;

- -

- Gene–environment interactions;

- -

- Epigenetic regulation of non-candidate genes.

- -

- GBS values are NOT disease probabilities;

- -

- GBS cannot be compared to population PRS percentiles (e.g., cannot say “this individual is in the top 10% of risk”);

- -

- GBS is suitable ONLY for relative within-family comparison;

- -

- Absolute GBS values have no clinical meaning outside this family context.

2.5. DNA Methylation Analysis

2.5.1. Peripheral Blood Methylation as a Proxy Biomarker

- Tissue-specific regulation: Brain and blood cells have distinct epigenetic landscapes due to different developmental origins, environmental exposures, and regulatory mechanisms.

- Cell-type composition: Peripheral blood consists of mixed cell populations (lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes), each with unique methylation profiles. Bulk blood methylation represents an average across these cell types.

- Uncertain concordance: Whether blood APOE methylation correlates with brain APOE methylation remains uncertain. Some studies report modest correlations (r = 0.3–0.5) for certain loci, while others show tissue-specific patterns with no cross-tissue concordance.

- Systemic vs. local effects: Blood methylation may reflect systemic processes (inflammation, oxidative stress) rather than brain-specific AD pathology. Therefore, blood methylation should not be interpreted as directly reflecting brain epigenetic states, and our findings require validation in brain tissue before conclusions about AD pathophysiology can be drawn.

2.5.2. Methylation Profiling Using Illumina EPICv2 Array

2.5.3. Methylation Data Pre-Processing and Quality Control

- -

- Background correction and normalization using the functional normalization (funnorm) method to adjust for technical variation;

- -

- Probe filtering:

- ∗

- Probes with detection p-value > 0.01 in any sample;

- ∗

- Probes overlapping known SNPs (MAF > 0.01 in East Asian populations);

- ∗

- Cross-reactive probes;

- ∗

- Probes on sex chromosomes (for consistency across samples);

- -

- Sample quality assessment: All seven samples exhibited high-quality metrics (median detection p-value < 0.001).

2.5.4. Candidate Gene-Specific Methylation Analysis

2.5.5. Functional Annotation and Clustering

- -

- KYCG (Know Your CpGs) database (https://zhou-lab.github.io/sesame/dev/KYCG.html) (accessed via sesame package v1.18.0) (accessed on 15 December 2025) for CpG-centric functional annotations;

- -

- gProfiler2 (v0.2.1) (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/) (accessed on 15 December 2025) for pathway enrichment analysis.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.6.2. Familial Aggregation and Generational Trends

2.6.3. Gene-Gene and Genotype–Methylation Correlations

- -

- Pairwise correlations between gene-specific risk allele counts (gene–gene interactions);

- -

- Correlations between SNP risk allele counts and mean methylation beta values for each gene (genotype–methylation relationships).

2.6.4. APOE ε4 Carrier Status Comparison

2.7. APOE Genotype Determination

2.8. Software and Data Visualization

- -

- R (v4.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for correlation analysis, ICC calculation, and methylation data processing;

- -

- Python (v3.9.12, Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) for data manipulation and visualization:

- pandas (v1.5.3) for data manipulation;

- scipy (v1.10.1) for statistical tests;

- matplotlib (v3.7.1) and seaborn (v0.12.2) for data visualization.

- -

- PLINK (v1.9, https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/, accessed on 20 January 2026) for genetic data quality control and file format conversion.

3. Results

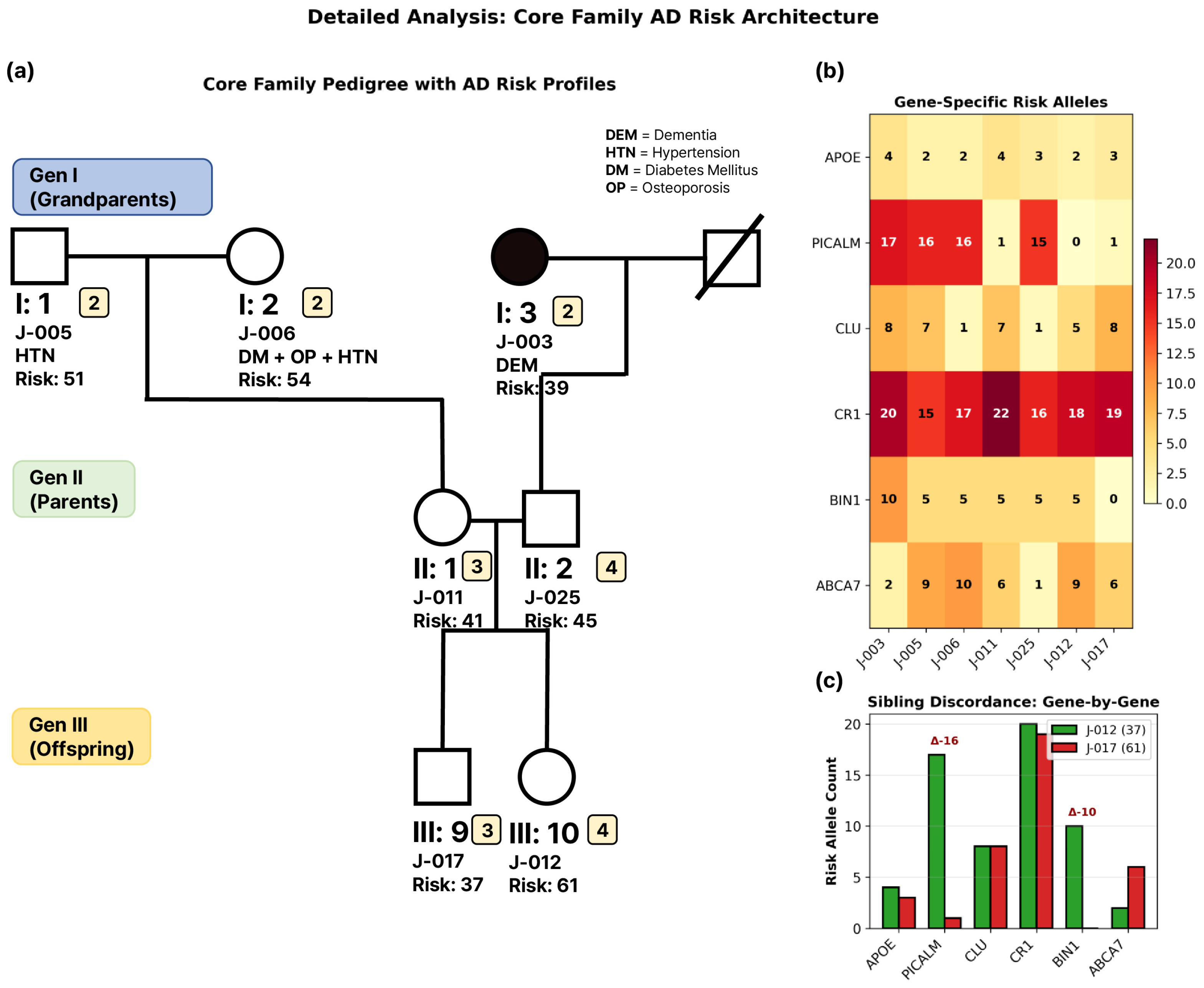

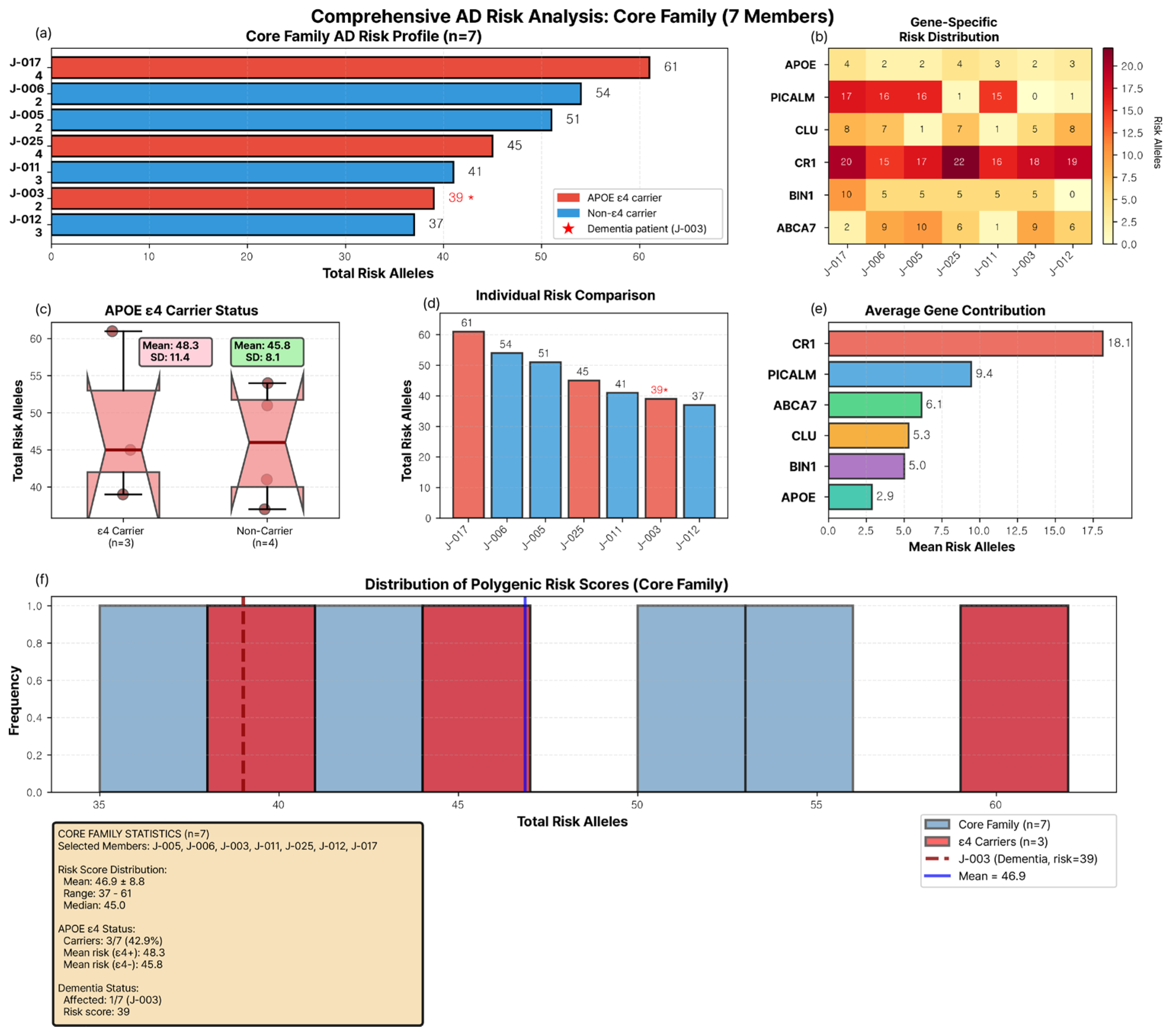

3.1. Core Family Structure and Clinical Characteristics

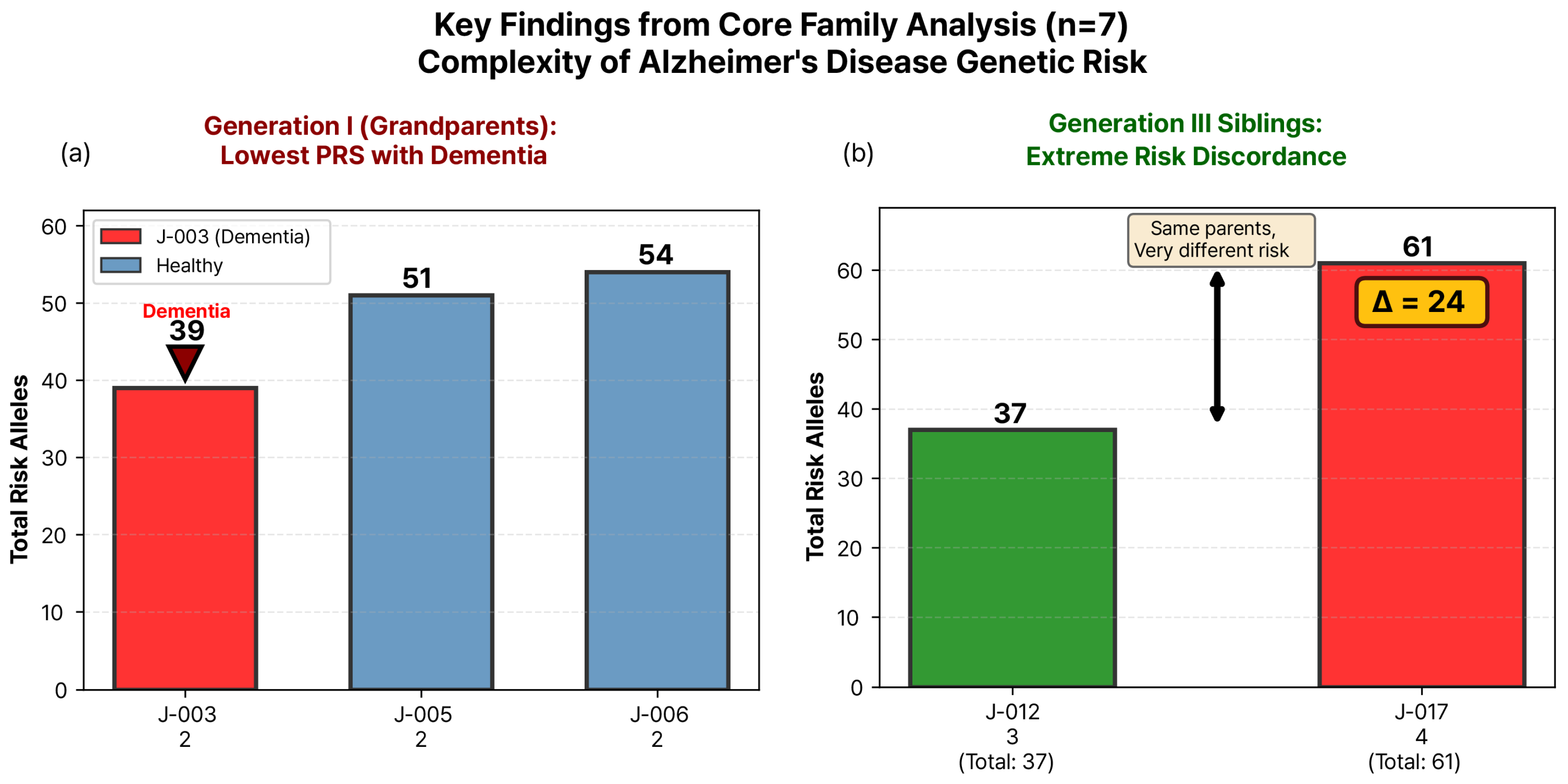

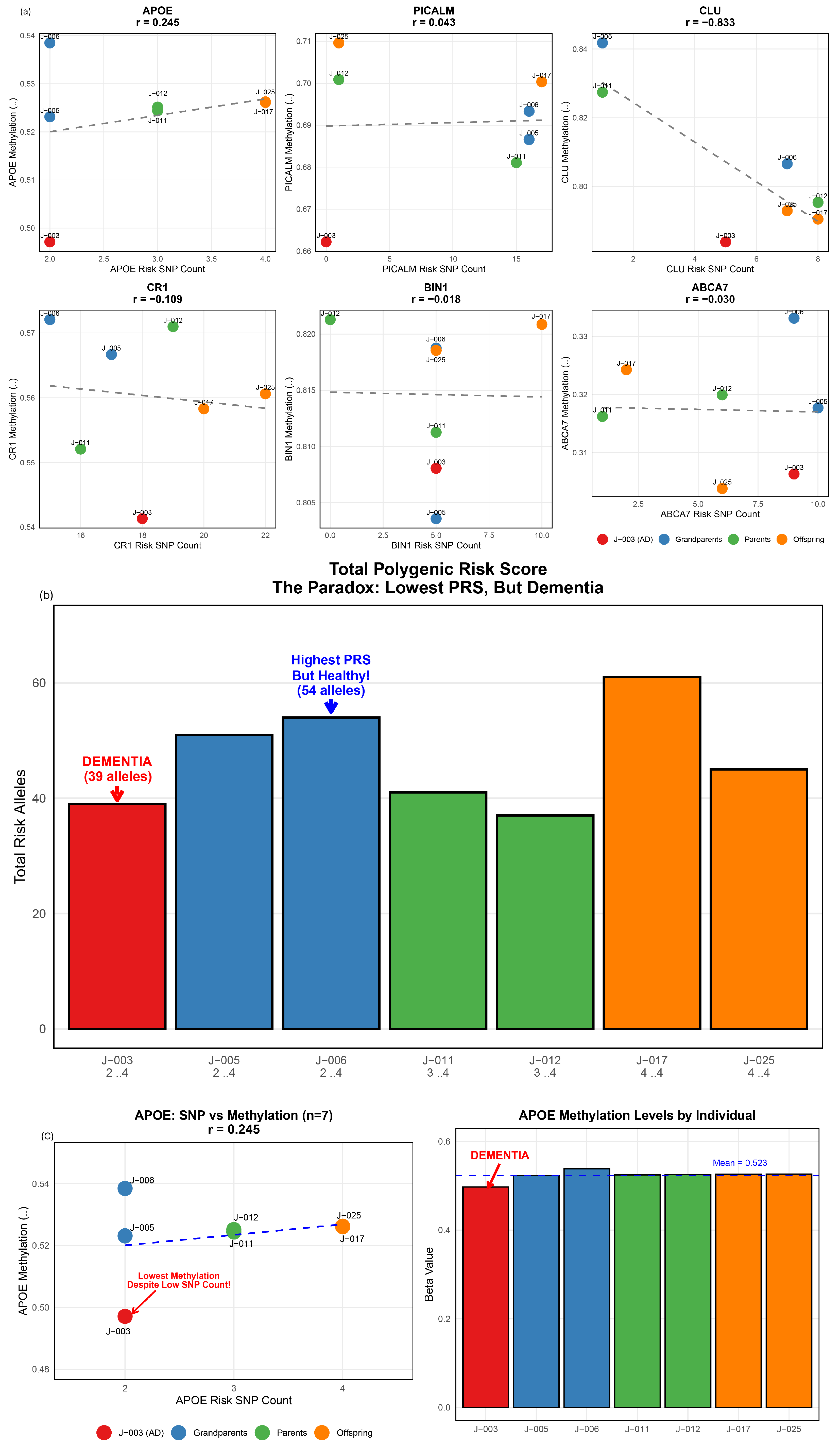

3.2. Genetic Burden Score Distribution and Generation I Pattern

3.3. Extreme Sibling Discordance in Generation III

3.4. APOE ε4 Carrier Status and Genetic Burden

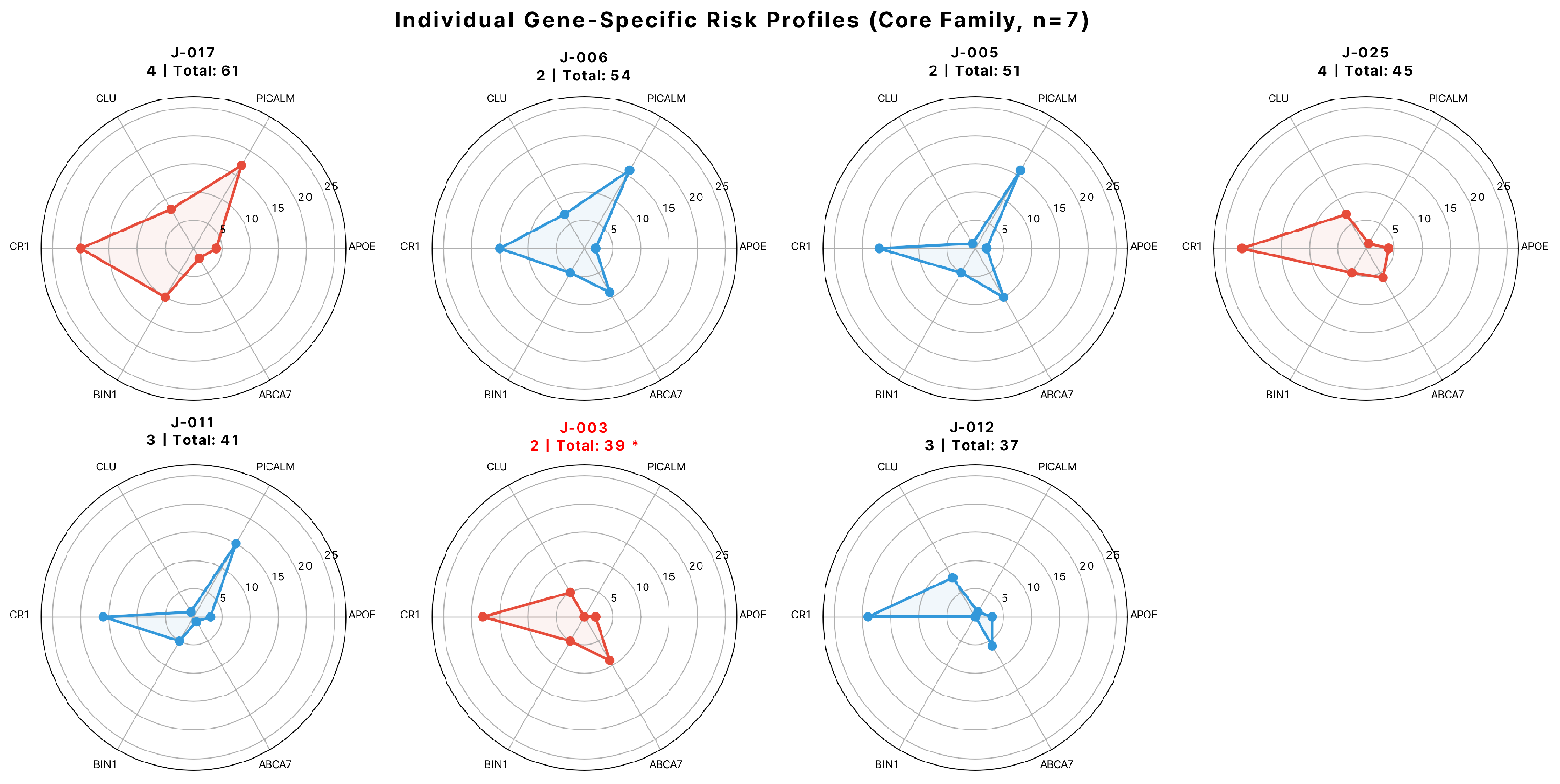

3.5. Gene-Specific Contributions to Family-Wide Genetic Burden

3.6. Gene–Gene Correlations and Individual Risk Profiles

3.7. Intergenerational Patterns of Genetic Burden

3.8. APOE Methylation Patterns in Relation to Genetic Burden

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| GBS | Polygenic risk score |

| PICALM | Phosphatidylinositol-binding clathrin assembly protein |

| CLU | clusterin |

| CR1 | Complement receptor 1 |

| BIN1 | Bridging integrator 1 |

| ABCA7 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 7 |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

References

- Zhang, N.; Chai, S.; Wang, J. Assessing and projecting the global impacts of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Public Health 2025, 12, 1453489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, R.Z.; den Braber, A.; Verberk, I.M.; Boonkamp, L.; Wilson, D.H.; Ligthart, L.; Teunissen, C.E.; de Geus, E.J. Heritability of Alzheimer’s disease plasma biomarkers: A nuclear twin family design. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e14269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Leonenko, G.; Schmidt, K.M.; Hill, M.; Myers, A.J.; Shoai, M.; de Rojas, I.; Tesi, N.; Holstege, H.; van der Flier, W.M. What does heritability of Alzheimer’s disease represent? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsodendris, N.; Nelson, M.R.; Rao, A.; Huang, Y. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer’s disease: Findings, hypotheses, and potential mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2022, 17, 73–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Wu, T.; Dai, J.; Cai, J.; Zhai, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Sun, T. Knowledge domains and emerging trends of genome-wide association studies in alzheimer’s disease: A bibliometric analysis and visualization study from 2002 to 2022. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0295008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Ryan, J.; Orchard, S.G.; Robb, C.; Woods, R.L.; Wolfe, R.; Renton, A.E.; Goate, A.M.; Brodtmann, A.; Shah, R.C. Validation of newly derived polygenic risk scores for dementia in a prospective study of older individuals. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 5333–5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, M.; Lee, A.J.; Reyes-Dumeyer, D.; Tosto, G.; Faber, K.; Goate, A.; Renton, A.; Chao, M.; Boeve, B.; Cruchaga, C. Polygenic risk score penetrance & recurrence risk in familial Alzheimer disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2023, 10, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panitch, R.; Sahelijo, N.; Hu, J.; Nho, K.; Bennett, D.A.; Lunetta, K.L.; Au, R.; Stein, T.D.; Farrer, L.A.; Jun, G.R. APOE genotype-specific methylation patterns are linked to Alzheimer disease pathology and estrogen response. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Plano, L.M.; Saitta, A.; Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A. Epigenetic changes in Alzheimer’s disease: DNA methylation and histone modification. Cells 2024, 13, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.Y.; Liu, J.Y.; Fang, C.L.; Deng, Y.P.; Zhang, Y. DNA methylation: The epigenetic mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Ibrain 2023, 9, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Better, M.A. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 1598–1695. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, M.O.; van der Lee, S.J.; Hulsman, M.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.; Scheltens, P.; Bank, N.B.; Seelaar, H.; van Swieten, J.C.; Kaat, L.D.; Holstege, H. Mapping the genetic landscape of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in a cohort of 36 families. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, A.; Kikuchi, M.; Hara, N.; Ikeuchi, T. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: An East Asian perspective. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 68, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.J.; Renton, A.E.; Fulton-Howard, B.; Podlesny-Drabiniok, A.; Marcora, E.; Goate, A.M. The complex genetic architecture of Alzheimer’s disease: Novel insights and future directions. eBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimzadeh, N.; Srinivasan, S.S.; Zhang, J.; Swarup, V. Gene networks and systems biology in Alzheimer’s disease: Insights from multi-omics approaches. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 3587–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkle, B.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Sims, R.; Bis, J.C.; Damotte, V.; Naj, A.C.; Boland, A.; Vronskaya, M.; Van Der Lee, S.J.; Amlie-Wolf, A.; et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellenguez, C.; Küçükali, F.; Jansen, I.E.; Kleineidam, L.; Moreno-Grau, S.; Amin, N.; Naj, A.C.; Campos-Martin, R.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Andrade, V.; et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, I.E.; Savage, J.E.; Watanabe, K.; Bryois, J.; Williams, D.M.; Steinberg, S.; Sealock, J.; Karlsson, I.K.; Hägg, S.; Athanasiu, L.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.C.; Ibrahim-Verbaas, C.A.; Harold, D.; Naj, A.C.; Sims, R.; Bellenguez, C.; DeStafano, A.L.; Bis, J.C.; Beecham, G.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; et al. Meta-Analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escott-Price, V.; Schmidt, K.M. Pitfalls of predicting age-related traits by polygenic risk scores. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2023, 87, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Dove, A.; Dunk, M.M.; Qi, X.; Bennett, D.A.; Xu, W. Association of cognitive reserve with the risk of dementia in the UK Biobank: Role of polygenic factors. Br. J. Psychiatry 2024, 224, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacher, M.; Canovas, R.; Laws, S.M.; Doecke, J.D. A comprehensive multi-omics analysis reveals unique signatures to predict Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Bioinform. 2024, 4, 1390607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, R.; Cardone, K.M.; Bradford, Y.; Moore, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Moore, J.H.; Shen, L.; Kim, D.; Ritchie, M.D. Integrative multi-omics approaches identify molecular pathways and improve Alzheimer’s disease risk prediction. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e70886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.L.; Manuel, A.M.; Liu, A.; Leng, B.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Z. Unveiling Gene Interactions in Alzheimer’s Disease by Integrating Genetic and Epigenetic Data with a Network-Based Approach. Epigenomes 2024, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Zhou, S.; Wu, H.; Forgetta, V.; Greenwood, C.M.; Richards, J.B. Individuals with common diseases but with a low polygenic risk score could be prioritized for rare variant screening. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fernandes, B.S.; Liu, A.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Z.; Dai, Y. GRPa-PRS: A risk stratification method to identify genetically-regulated pathways in polygenic diseases. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e70779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visscher, P.M.; Yengo, L.; Cox, N.J.; Wray, N.R. Discovery and implications of polygenicity of common diseases. Science 2021, 373, 1468–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, W.; Gao, T.; Yan, Y.; Wang, T.; Zheng, C.; Zeng, P. Influence and role of polygenic risk score in the development of 32 complex diseases. J. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 04071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Tan, T.; Nehzati, S.M.; Bennett, M.; Turley, P.; Benjamin, D.J.; Young, A.S. Family-based genome-wide association study designs for increased power and robustness. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nativio, R.; Lan, Y.; Donahue, G.; Sidoli, S.; Berson, A.; Srinivasan, A.R.; Shcherbakova, O.; Amlie-Wolf, A.; Nie, J.; Cui, X. An integrated multi-omics approach identifies epigenetic alterations associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 1024–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.G.; Hannon, E.; De Jager, P.L.; Chibnik, L.; Lott, S.J.; Condliffe, D.; Smith, A.R.; Haroutunian, V.; Troakes, C.; Al-Sarraj, S. Elevated DNA methylation across a 48-kb region spanning the HOXA gene cluster is associated with Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbaum, M.; Pearson, A.; Ortiz, C.; Mullan, M.; Crawford, F.; Ojo, J.; Bachmeier, C. APOE4 expression disrupts tau uptake, trafficking, and clearance in astrocytes. Glia 2024, 72, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-I.; Yu, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, B.; Jang, M.J.; Jo, H.; Kim, N.Y.; Pak, M.E.; Kim, J.K.; Cho, S. Astrocyte priming enhances microglial Aβ clearance and is compromised by APOE4. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, A.J.; Fulton-Howard, B.; Riaz, M.; Laws, S.; Sebra, R.; Ryan, J.; Consortium, A.s.D.G.; Renton, A.E.; Goate, A.M.; Masters, C.L. Polygenic score modifies risk for Alzheimer’s disease in APOE ε4 homozygotes at phenotypic extremes. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2021, 13, e12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, Y.; Priyanka, A.; Xu, L.; Wang, W.; Thrush-Evensen, K.; Gonzalez, J.; Borrus, D.; Kasamoto, J.; Sehgal, R.; Zou, G. Beyond the Genotype: A Multi-Omic Analysis of APOEe4’s Role in Alzheimer’s Disease. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klibaner-Schiff, E.; Simonin, E.M.; Akdis, C.A.; Cheong, A.; Johnson, M.M.; Karagas, M.R.; Kirsh, S.; Kline, O.; Mazumdar, M.; Oken, E. Environmental exposures influence multigenerational epigenetic transmission. Clin. Epigenetics 2024, 16, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafavi, H.; Harpak, A.; Agarwal, I.; Conley, D.; Pritchard, J.K.; Przeworski, M. Variable prediction accuracy of polygenic scores within an ancestry group. eLife 2020, 9, e48376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Button, K.S.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Mokrysz, C.; Nosek, B.A.; Flint, J.; Robinson, E.S.; Munafò, M.R. Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbrodt, F.D.; Perugini, M. At what sample size do correlations stabilize? J. Res. Personal. 2013, 47, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Dumeyer, D.; Faber, K.; Vardarajan, B.; Goate, A.; Renton, A.; Chao, M.; Boeve, B.; Cruchaga, C.; Pericak-Vance, M.; Haines, J.L. The National Institute on aging late-onset Alzheimer’s disease family based study: A resource for genetic discovery. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.G.; Pishva, E.; Shireby, G.; Smith, A.R.; Roubroeks, J.A.; Hannon, E.; Wheildon, G.; Mastroeni, D.; Gasparoni, G.; Riemenschneider, M. A meta-analysis of epigenome-wide association studies in Alzheimer’s disease highlights novel differentially methylated loci across cortex. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, A.S.; Rutledge, J.C.; Medici, V. DNA methylation alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Environ. Epigenetics 2017, 3, dvx008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, M.; Malavolti, M.; Garuti, C.; Tondelli, M.; Marchesi, C.; Vinceti, M.; Filippini, T. Environmental and lifestyle risk factors for early-onset dementia: A systematic review. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2022, 93, e2022336. [Google Scholar]

- Caraci, F.; Leggio, G.M.; Drago, F.; Salomone, S. Epigenetic drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: Hopes and challenges. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 75, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, C.H. Challenging the utility of polygenic scores for social science: Environmental confounding, downward causation, and unknown biology. Behav. Brain Sci. 2023, 46, e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.F.; Villaman, C.; Leu, C.; Lal, D.; Mata, I.; Klein, A.D.; Pérez-Palma, E. Polygenic score analysis identifies distinct genetic risk profiles in Alzheimer’s disease comorbidities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Matan-Lithwick, S.; Wang, Y.; De Jager, P.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Felsky, D. Multi-omic integration via similarity network fusion to detect molecular subtypes of ageing. Brain Commun. 2023, 5, fcad110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Savina, E.A.; Tatarinova, T.V.; Orlov, Y.L. Population and ancestry specific variation in disease susceptibility. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1267719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Chromosome Location (GRCh37/hg19) | Function in AD Pathology |

|---|---|---|

| APOE | chr19: 45,409,011–45,412,650 | Amyloid-β metabolism and clearance |

| PICALM | chr11: 85,673,738–85,782,667 | Endocytosis and tau pathology |

| CLU | chr8: 27,453,434–27,469,869 | Amyloid clearance and chaperone activity |

| CR1 | chr1: 207,494,290–207,667,439 | Immune response and amyloid clearance |

| BIN1 | chr2: 127,803,005–127,897,976 | Tau pathology and endocytic trafficking |

| ABCA7 | chr19: 1,040,673–1,084,340 | Lipid metabolism and amyloid processing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eom, J.-H.; Cho, M.-Y.; Kim, J.-W.; Kim, Y.; Yang, S.-J.; Hwang, J.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, Y.-Y.; Baek, H. Genetic Burden and APOE Methylation in a Korean Multi-Generational Alzheimer’s Disease Family: An Exploratory Multi-Omics Case Study. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020066

Eom J-H, Cho M-Y, Kim J-W, Kim Y, Yang S-J, Hwang J, Lee D, Kim H-S, Kim Y-Y, Baek H. Genetic Burden and APOE Methylation in a Korean Multi-Generational Alzheimer’s Disease Family: An Exploratory Multi-Omics Case Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(2):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020066

Chicago/Turabian StyleEom, Je-Hyun, Mu-Yeol Cho, Ji-Won Kim, Yunwoo Kim, Seung-Jo Yang, Jiyoung Hwang, Dahye Lee, Hye-Sung Kim, Young-Youn Kim, and Hanseung Baek. 2026. "Genetic Burden and APOE Methylation in a Korean Multi-Generational Alzheimer’s Disease Family: An Exploratory Multi-Omics Case Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 2: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020066

APA StyleEom, J.-H., Cho, M.-Y., Kim, J.-W., Kim, Y., Yang, S.-J., Hwang, J., Lee, D., Kim, H.-S., Kim, Y.-Y., & Baek, H. (2026). Genetic Burden and APOE Methylation in a Korean Multi-Generational Alzheimer’s Disease Family: An Exploratory Multi-Omics Case Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(2), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16020066