The Fibrinogen-to-Albumin Ratio in Endometriosis: A Step Toward Personalized Non-Invasive Diagnostics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

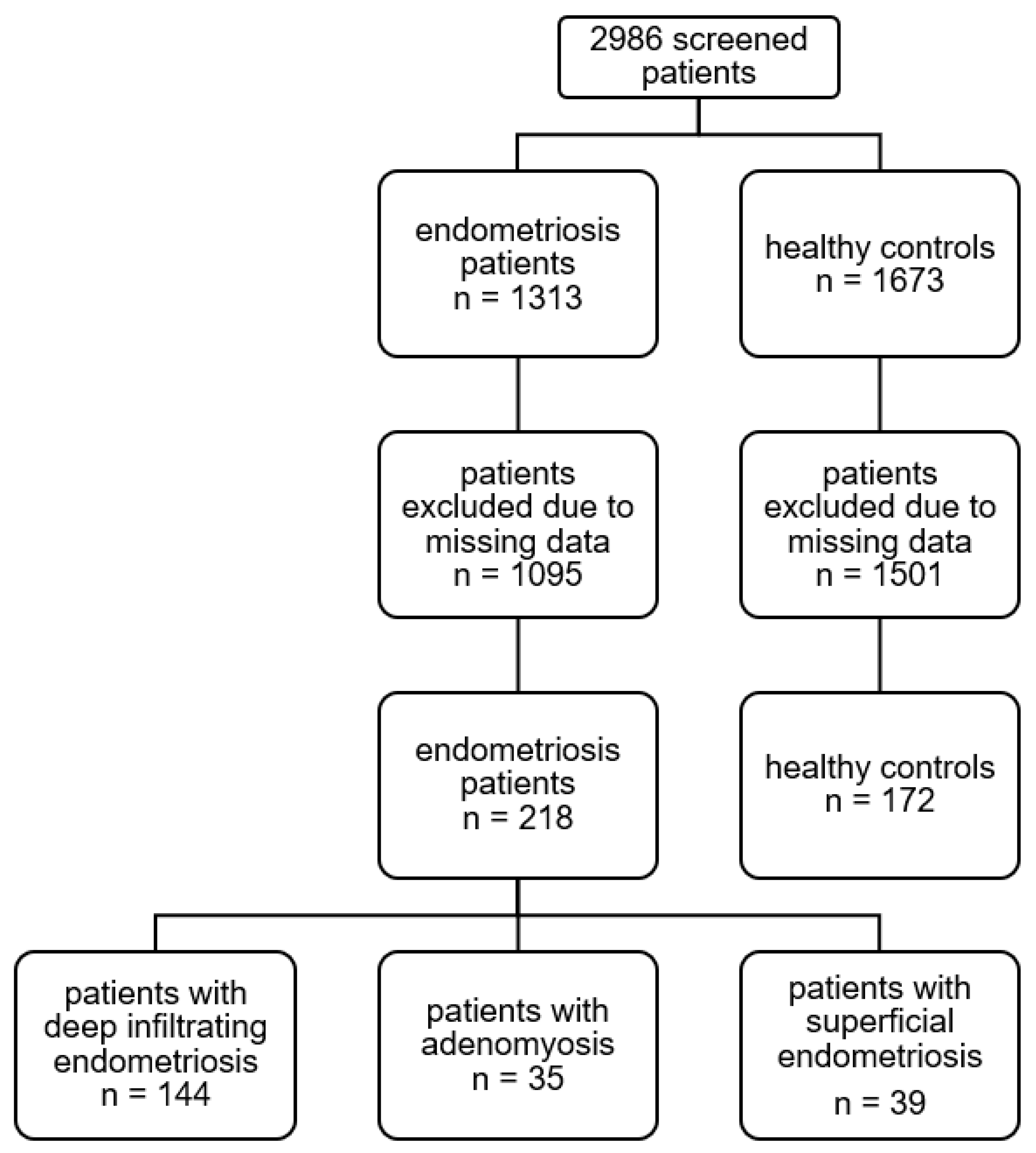

Study Population

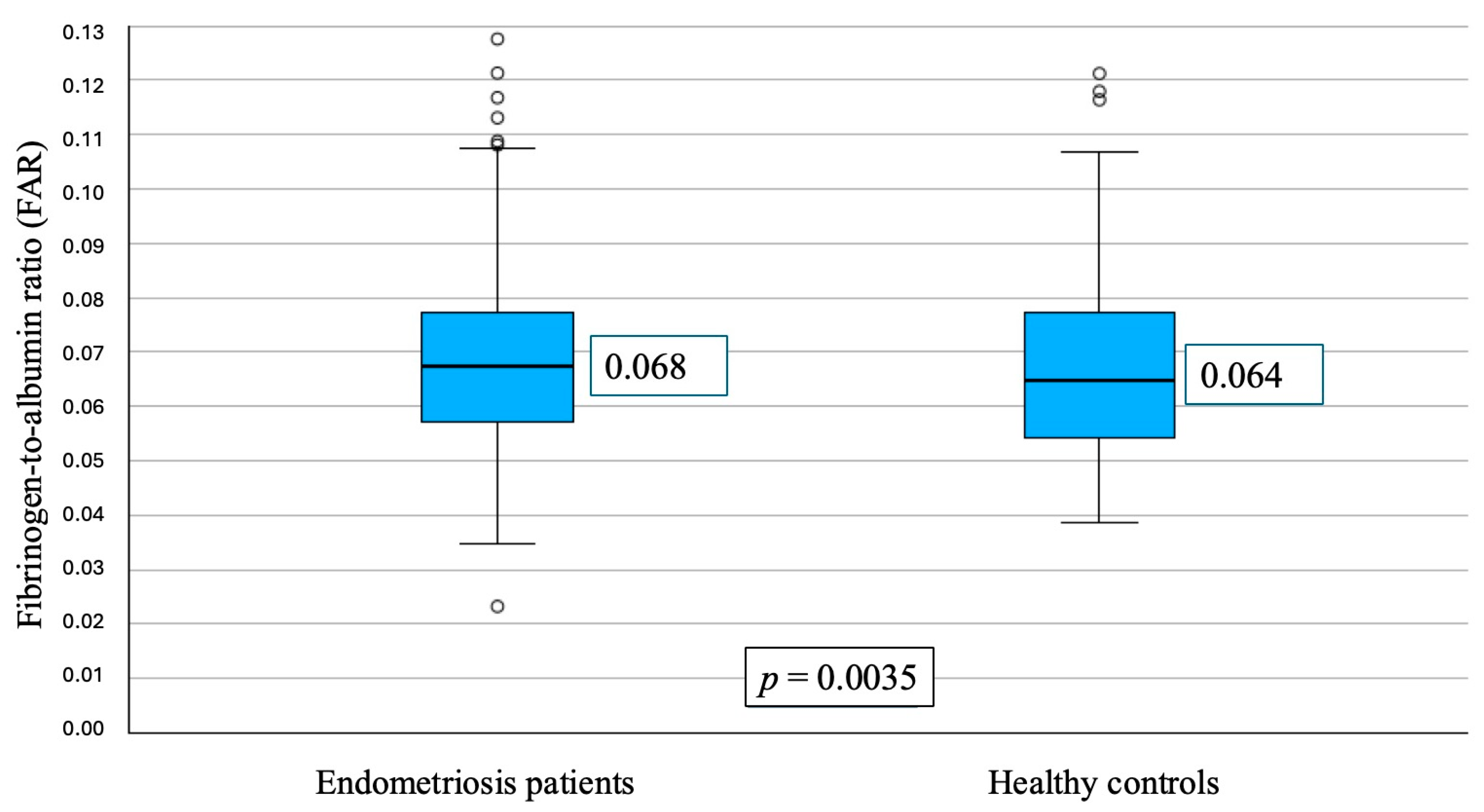

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

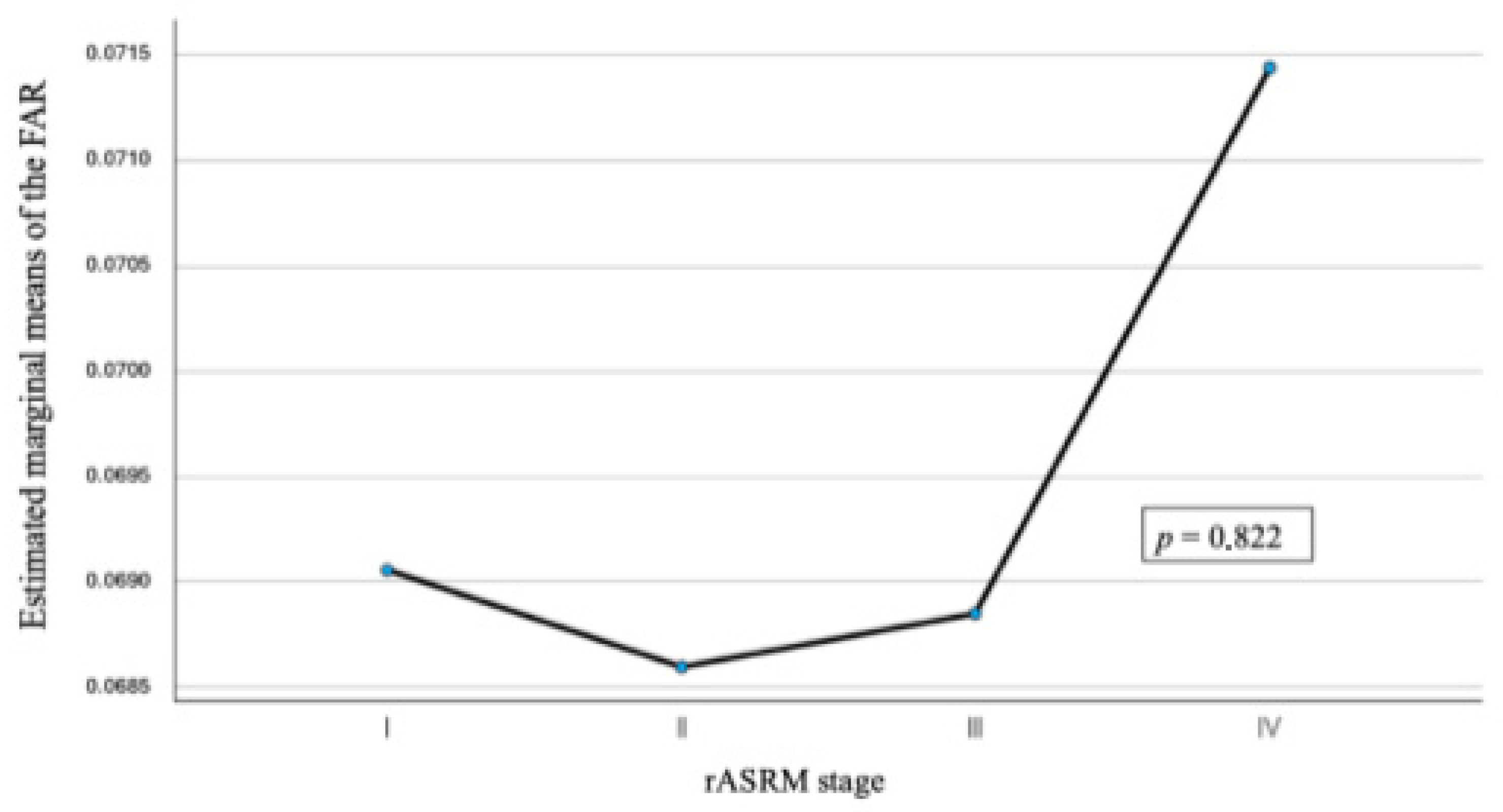

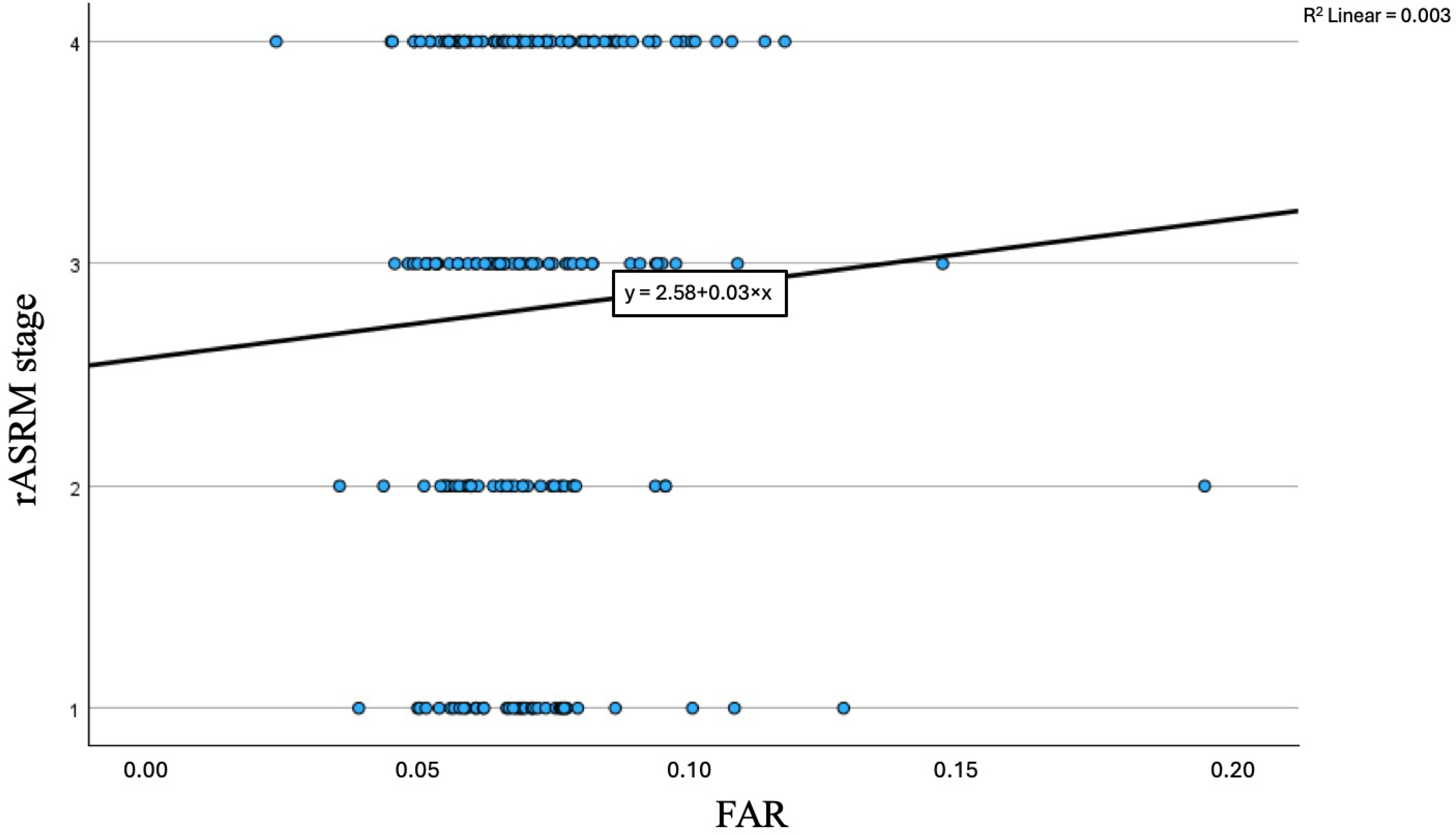

3.2. FAR and Disease Severity

3.3. FAR and Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

3.4. Summary of Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Patient Flowchart

Appendix A.2. Patient Characteristics

| Endometriosis * | Controls ** | p-Value *** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 218 (55.90%) | 172 (44.10%) | - |

| Age (median, IQR) | 32.00 (28.00–38.00) | 33.50 (26.00–41.75) | 0.38 |

| BMI (median, IQR) | 22.40 (20.60–26.70) | 22.60 (20.08–25.05) | 0.37 |

| G (median, IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | <0.01 |

| P (median, IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | <0.001 |

| HT (n, %) | 33 (21.1%) | 19 (14.8%) | 0.16 |

| PT (n, %) | 55 (35%) | 15 (11.1%) | <0.001 |

| rASRM (n, %) | |||

| I | 39 (17.9%) | - | - |

| II | 38 (17.4%) | - | - |

| III | 54 (24.8%) | - | - |

| IV | 74 (33.9%) | - | - |

| Adenomyosis (n, %) | 35 (16.1%) | - | - |

| DIE (n, %) | 144 (66.1%) | - | - |

| Lab result (median, IQR) | |||

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.10 (0.04–0.32) | 0.09 (0.033–0.21) | 0.04 |

| LEU (G/L) | 6.96 (5.64–8.85) | 6.98 (5.63–8.69) | 0.74 |

| THR (G/L) | 270.50 (238.00–308.00) | 263.00 (226.25–302.00) | 0.05 |

| TT (s) | 16.10 (15.60–16.80) | 16.30 (15.70–17.23) | 0.16 |

| PT (%) | 89.00 (79.75–103.25) | 88,50 (77.25–100.75) | 0.29 |

| aPTT (s) | 34.80 (32.70–37.45) | 34.70 (32.40–37.80) | 0.89 |

| FIB (g/L) | 2.98 (2.68–3.44) | 2.94 (2.46–3.30) | 0.03 |

| ALB (g/L) | 44.85 (42.70–46.73) | 45.20 (43.30–47.40) | 0.08 |

| CA-125 (kU/L) | 36.10 (16.50–89.05) | 19.40 (13.30–37.65) | 0.01 |

References

- Saunders, P.T.K.; Horne, A.W. Endometriosis: Etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell 2021, 184, 2807–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B.; Szyłło, K.; Romanowicz, H. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis, Treatment and Genetics (Review of Literature). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keckstein, J.; Hudelist, G. Classification of deep endometriosis (DE) including bowel endometriosis: From r-ASRM to #Enzian-classification. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obs. Gynaecol. 2021, 71, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, C.; Vandenabeele, B.; Fieuws, S.; Spiessens, C.; Timmerman, D.; D’Hooghe, T. High prevalence of endometriosis in infertile women with normal ovulation and normospermic partners. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamceva, J.; Uljanovs, R.; Strumfa, I. The Main Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehedintu, C.; Plotogea, M.N.; Ionescu, S.; Antonovici, M. Endometriosis still a challenge. J. Med. Life 2014, 7, 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Szyllo, K.; Tchorzewski, H.; Banasik, M.; Glowacka, E.; Lewkowicz, P.; Kamer-Bartosinska, A. The involvement of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of endometriotic tissues overgrowth in women with endometriosis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2003, 12, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Ho, H.-N. The role of cytokines in endometriosis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2003, 49, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.; Lin, Q.; Zhu, T.; Li, T.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Is there a correlation between inflammatory markers and coagulation parameters in women with advanced ovarian endometriosis? BMC Womens Health 2019, 19, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, J.; Mielczarek-Palacz, A.; Kondera-Anasz, Z. Imbalance in cytokines from interleukin-1 family—Role in pathogenesis of endometriosis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2012, 68, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickiewicz, D.; Chrobak, A.; Gmyrek, G.B.; Halbersztadt, A.; Gabryś, M.S.; Goluda, M.; Chełmońska-Soyta, A. Diagnostic accuracy of interleukin-6 levels in peritoneal fluid for detection of endometriosis. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. 2013, 288, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiu, C.V.; Moga, M.A.; Elena Neculau, A.; Bălan, A.; Scârneciu, I.; Dragomir, R.M.; Dull, A.-M.; Chicea, L.-M. Biomarkers for the Noninvasive Diagnosis of Endometriosis: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lousse, J.-C.; Van Langendonckt, A.; Defrere, S.; Ramos, R.G.; Colette, S.; Donnez, J. Peritoneal endometriosis is an inflammatory disease. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2012, 4, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Ye, Z.; Lin, X.; Zhang, S. Immunopathological insights into endometriosis: From research advances to future treatments. Semin. Immunopathol. 2025, 47, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herington, J.L.; Bruner-Tran, K.L.; Lucas, J.A.; Osteen, K.G. Immune interactions in endometriosis. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 7, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramiuk, M.; Grywalska, E.; Małkowska, P.; Sierawska, O.; Hrynkiewicz, R.; Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P. The Role of the Immune System in the Development of Endometriosis. Cells 2022, 11, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wu, N.; Xue, Q. Macrophages in endometriosis: Key roles and emerging therapeutic opportunities-a narrative review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2025, 23, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Pavez, T.N.; Martínez-Esparza, M.; Ruiz-Alcaraz, A.J.; Marín-Sánchez, P.; Machado-Linde, F.; García-Peñarrubia, P. The Role of Peritoneal Macrophages in Endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójtowicz, M.; Zdun, D.; Owczarek, A.J.; Skrzypulec-Plinta, V.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M. Evaluation of Proinflammatory Cytokines Concentrations in Plasma, Peritoneal, and Endometrioma Fluids in Women Operated on for Ovarian Endometriosis-A Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Wei, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, X. Peritoneal immune microenvironment of endometriosis: Role and therapeutic perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1134663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machairiotis, N.; Vasilakaki, S.; Thomakos, N. Inflammatory Mediators and Pain in Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeze, G.G.; Wu, L.; Alemu, B.K.; Wang, C.C.; Zhang, T. Changes in the number and activity of natural killer cells and its clinical association with endometriosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. FS Rev. 2024, 5, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xu, W.; Chen, F. Dysfunction of natural killer cells promotes immune escape and disease progression in endometriosis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1657605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Garcia, J.M.; Vannuzzi, V.; Donati, C.; Bernacchioni, C.; Bruni, P.; Petraglia, F. Endometriosis: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Leading to Fibrosis. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 30, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, T. Unveiling the Mechanisms of Pain in Endometriosis: Comprehensive Analysis of Inflammatory Sensitization and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, C.; Wang, H.; Fang, H. Genomic Evidence Supports the Recognition of Endometriosis as an Inflammatory Systemic Disease and Reveals Disease-Specific Therapeutic Potentials of Targeting Neutrophil Degranulation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 758440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, E.; Argento, F.R.; Borghi, S.; Giurranna, E.; Nencini, F.; Cirillo, M.; Fatini, C.; Taddei, N.; Coccia, M.E.; Fiorillo, C.; et al. Fibrinogen Structural Changes and Their Potential Role in Endometriosis-Related Thrombosis. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, G.; HazırBulan, A.; Atalmış, H.A.; Yüksel, İ.T.; Sözen, I.; Koçbıyık, A.; Kocadal, N.Ç.; Alkış, İ. Diagnostic Power of the Fibrinogen-to-Albumin Ratio for Estimating Malignancy in Patients with Adnexal Masses: A Methodological Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Koga, K.; Missmer, S.A.; Taylor, R.N.; Viganò, P. Endometriosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, M. Endometriosis: Future Biological Perspectives for Diagnosis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, S.; Zhang, C. The interplay between systemic inflammatory factors and endometriosis: A bidirectional mendelian randomization study. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2024, 165, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunselman, G.a.J.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, M.; Duffy, J.; Davis, C.J.; Nieves Plana, M.; Khan, K.S. International Collaboration to Harmonise Outcomes and Measures for Endometriosis Diagnostic accuracy of cancer antigen 125 for endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 123, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pan, M.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, S. Research progress of CA125 in endometriosis: Teaching an old dog new tricks. Gynecol. Obstet. Clin. Med. 2022, 2, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorun, O.M.; Ratiu, A.; Citu, C.; Cerbu, S.; Gorun, F.; Popa, Z.L.; Crisan, D.C.; Forga, M.; Daescu, E.; Motoc, A. The Role of Inflammatory Markers NLR and PLR in Predicting Pelvic Pain in Endometriosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisenblat, V.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Shaikh, R.; Farquhar, C.; Jordan, V.; Scheffers, C.S.; Mol, B.W.J.; Johnson, N.; Hull, M.L. Blood biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD012179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolińska, W.; Draper, H.; Othman, L.; Thompson, C.; Girvan, S.; Cunningham, K.; Allen, J.; Rigby, A.; Phillips, K.; Guinn, B. Accuracy and utility of blood and urine biomarkers for the noninvasive diagnosis of endometriosis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. FS Rev. 2023, 4, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, C. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and CA125 Level as a Combined Biomarker for Diagnosing Endometriosis and Predicting Pelvic Adhesion Severity. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 896152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Guo, J.; Li, W.; Zheng, R.; Shang, H.; Wang, Y. Diagnostic value of the combination of circulating serum miRNAs and CA125 in endometriosis. Medicine 2023, 102, e36339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghaus, S.; Drazic, P.; Wölfler, M.; Mechsner, S.; Zeppernick, M.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Mueller, M.D.; Rothmund, R.; Vigano, P.; Becker, C.M.; et al. Multicenter evaluation of blood-based biomarkers for the detection of endometriosis and adenomyosis: A prospective non-interventional study. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obs. 2024, 164, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendo-Chalma, P.; Díaz-Landy, E.N.; Antonio-Véjar, V.; Ortiz Tejedor, J.G.; Reytor-González, C.; Simancas-Racines, D.; Bigoni-Ordóñez, G.D. Endometriosis: Challenges in Clinical Molecular Diagnostics and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, K.L.; Shafrir, A.; Laliberte, A.; Vitonis, A.F.; Garbutt, K.; DePari, M.; Becker, C.; Sasamoto, N.; Zondervan, K.T.; Missmer, S.A. Circulating inflammatory biomarkers and endometriosis lesion characteristics in the WisE consortium. npj Womens Health 2025, 3, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Moar, K.; Arora, T.K.; Maurya, P.K. Biomarkers of endometriosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 549, 117563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Q.; Liu, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, B. Preoperative fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio, a potential prognostic factor for patients with stage IB-IIA cervical cancer. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Yan, Y.; Gu, S.; Mao, K.; Zhang, J.; Huang, P.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, S.; Liang, J.; et al. A Novel Inflammation-Based Prognostic Score: The Fibrinogen/Albumin Ratio Predicts Prognoses of Patients after Curative Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 4925498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.-W.; An, L.; Lv, G.-Y. Albumin-fibrinogen ratio and fibrinogen-prealbumin ratio as promising prognostic markers for cancers: An updated meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Garlanda, C. Humoral Innate Immunity and Acute-Phase Proteins. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, D.A.; Fish, R.; de Vries, P.S.; Morrison, A.C.; Neerman-Arbez, M.; Wolberg, A.S. Regulation of Fibrinogen Synthesis. Thromb. Res. 2024, 242, 109134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolberg, A.S. Fibrinogen and fibrin: Synthesis, structure, and function in health and disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 21, 3005–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, C.; Kushner, I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeters, P.B.; Wolfe, R.R.; Shenkin, A. Hypoalbuminemia: Pathogenesis and Clinical Significance. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2019, 43, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremese, E.; Bruno, D.; Varriano, V.; Perniola, S.; Petricca, L.; Ferraccioli, G. Serum Albumin Levels: A Biomarker to Be Repurposed in Different Disease Settings in Clinical Practice. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Ding, D.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.-W. Evidence for a Hypercoagulable State in Women with Ovarian Endometriomas. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 22, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagiran, F.T.; Kali, Z.; Kirici, P.; Celik, O. Comparison of immunohistochemical characteristics of endometriomas with non-endometriotic benign ovarian cysts. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 7594–7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, A.; Dilbaz, B.; Engin-Üstün, Y. Comparison of serum markers of inflammation in endometrioma and benign ovarian cysts. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obs. 2025, 47, e-rbgo58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Li, D. Ferroptosis and oxidative stress in endometriosis: A systematic review of the literature. Medicine 2024, 103, e37421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.-G.; Wu, T.-T.; Zheng, Y.-Y.; Yang, H.-T.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Y.-T.; Xie, X. The Fibrinogen-to-Albumin Ratio Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: Findings from a Large Cohort. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2023, 16, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.; Zhang, S.; Ling, J.; Chen, Z.; Feng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, C.; Hou, T. Prognostic value of the fibrinogen albumin ratio index (FARI) in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients undergoing radiotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frontiers|Prognostic Role of Fibrinogen-to-Albumin Ratio in Patients with Gynecological Cancers: A Meta-Analysis. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1580940/full?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Li, B.; Deng, H.; Lei, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Sha, D. The prognostic value of fibrinogen to albumin ratio in malignant tumor patients: A meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 985377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.-L.; Chen, C.; Wu, J.; Cheng, J.-F.; He, F. The predictive value of fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio in the active, severe active, and poor prognosis of systemic lupus erythematosus: A single-center retrospective study. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathod, S.; Shanoo, A.; Acharya, N. Endometriosis: A Comprehensive Exploration of Inflammatory Mechanisms and Fertility Implications. Cureus 2024, 16, e66128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donkin, R.; Fung, Y.L.; Singh, I. Fibrinogen, Coagulation, and Ageing. Subcell. Biochem. 2023, 102, 313–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.-N.; Peng, Y.-Q.; Xu, X.; Shi, X.-L.; Peng, C.-X. Positive correlation between NLR and PLR in 10,458 patients with endometriosis in reproductive age in China. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, F.; Tahernia, H.; Ghaedi, A.; Bazrgar, A.; Khanzadeh, S. Diagnostic significance of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FAR | Mean | SD | Min/Max | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rASRM I | 0.069 | 0.016 | 0.038/0.123 | 0.82 |

| rASRM II | 0.069 | 0.024 | 0.035/0.194 | |

| rASRM III | 0.069 | 0.018 | 0.045/0.146 | |

| rASRM IV | 0.067 | 0.018 | 0.023/0.117 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Samson, L.; Mally, T.; Paternostro, C.; Bill, A.; Kuessel, L.; Bekos, C. The Fibrinogen-to-Albumin Ratio in Endometriosis: A Step Toward Personalized Non-Invasive Diagnostics. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010020

Samson L, Mally T, Paternostro C, Bill A, Kuessel L, Bekos C. The Fibrinogen-to-Albumin Ratio in Endometriosis: A Step Toward Personalized Non-Invasive Diagnostics. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamson, Lejla, Theresa Mally, Chiara Paternostro, Alfie Bill, Lorenz Kuessel, and Christine Bekos. 2026. "The Fibrinogen-to-Albumin Ratio in Endometriosis: A Step Toward Personalized Non-Invasive Diagnostics" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010020

APA StyleSamson, L., Mally, T., Paternostro, C., Bill, A., Kuessel, L., & Bekos, C. (2026). The Fibrinogen-to-Albumin Ratio in Endometriosis: A Step Toward Personalized Non-Invasive Diagnostics. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010020