Current Trends in Venous Thromboprophylaxis for Inpatient Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Evidence on Thromboprophylaxis in Hospitalized Patients

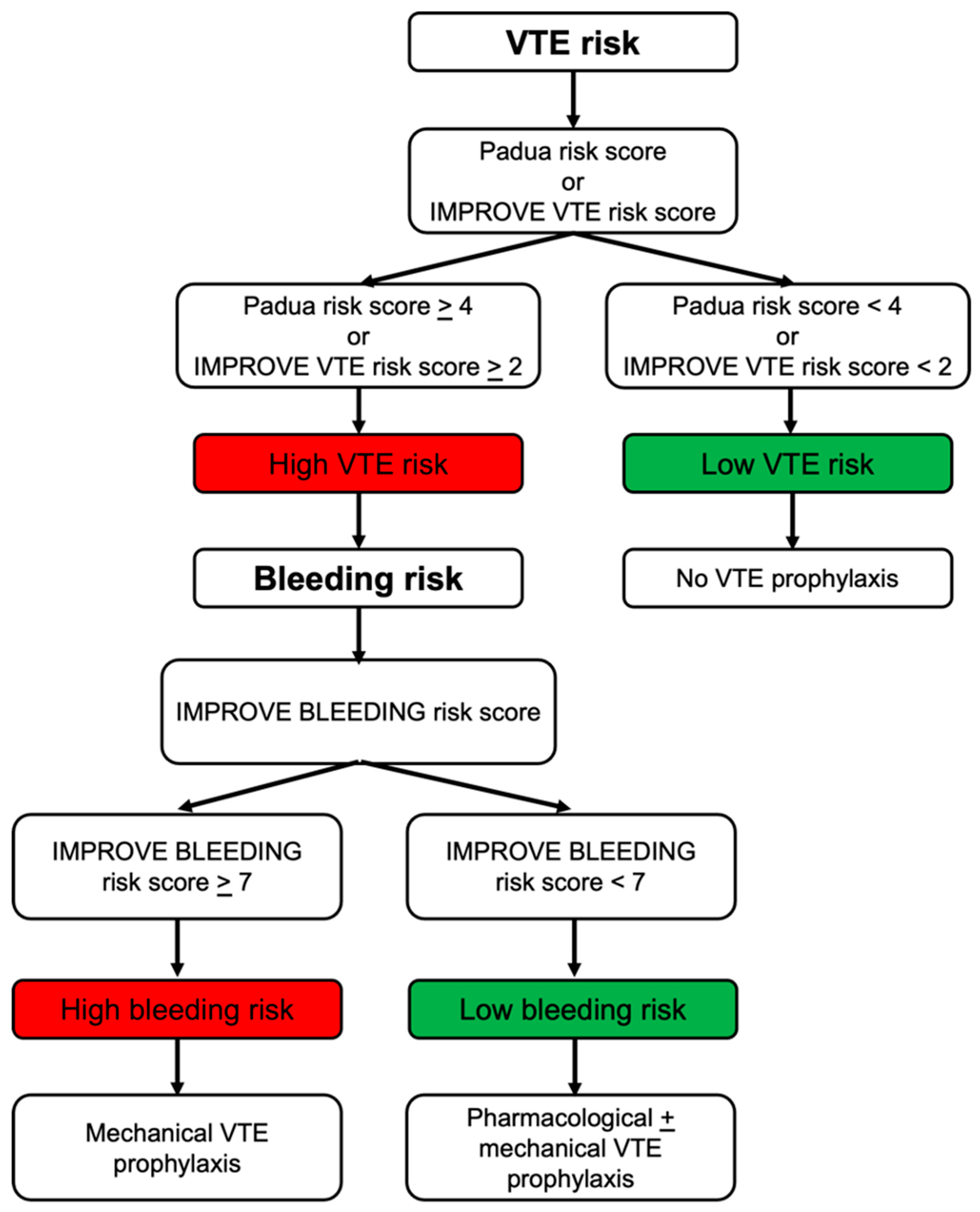

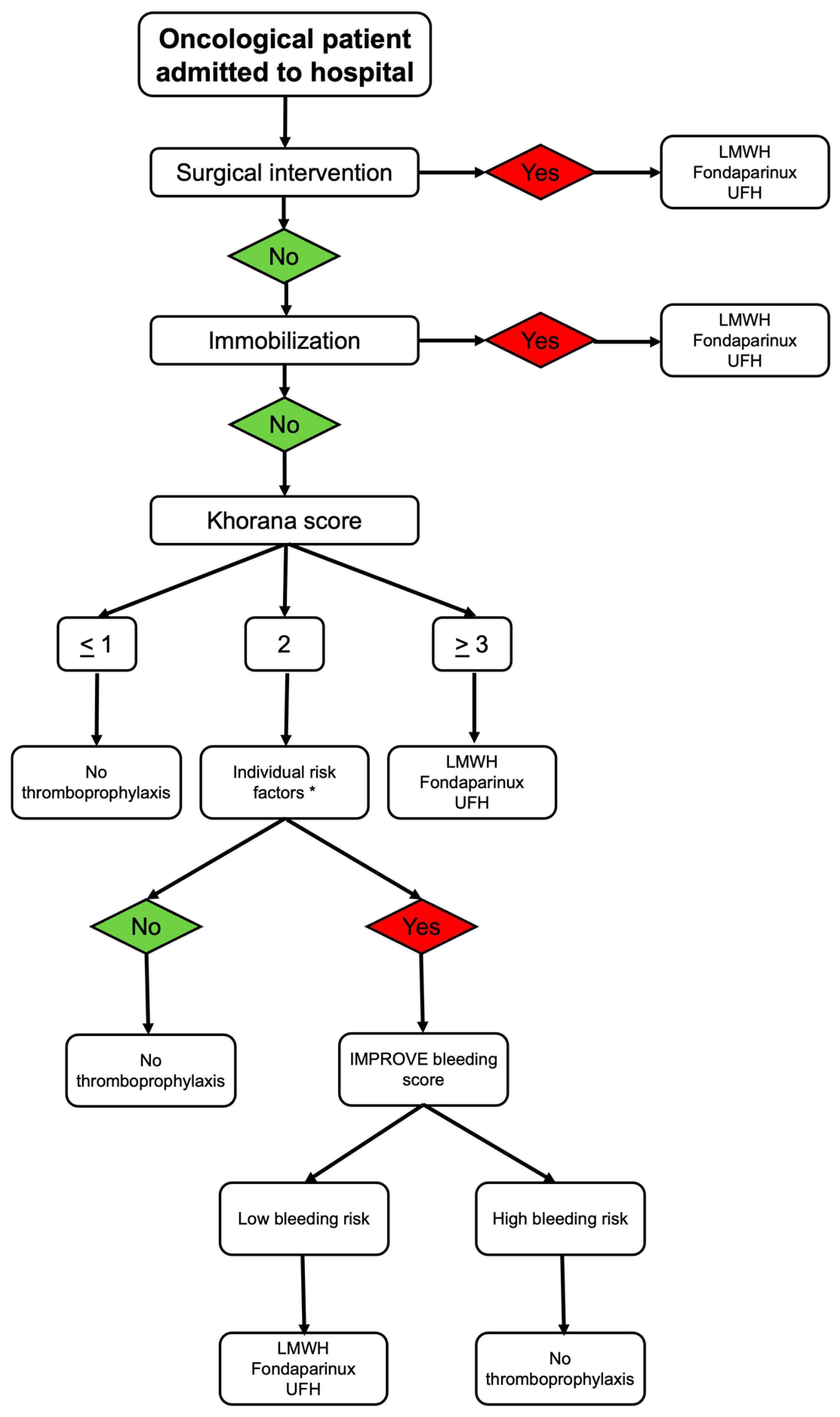

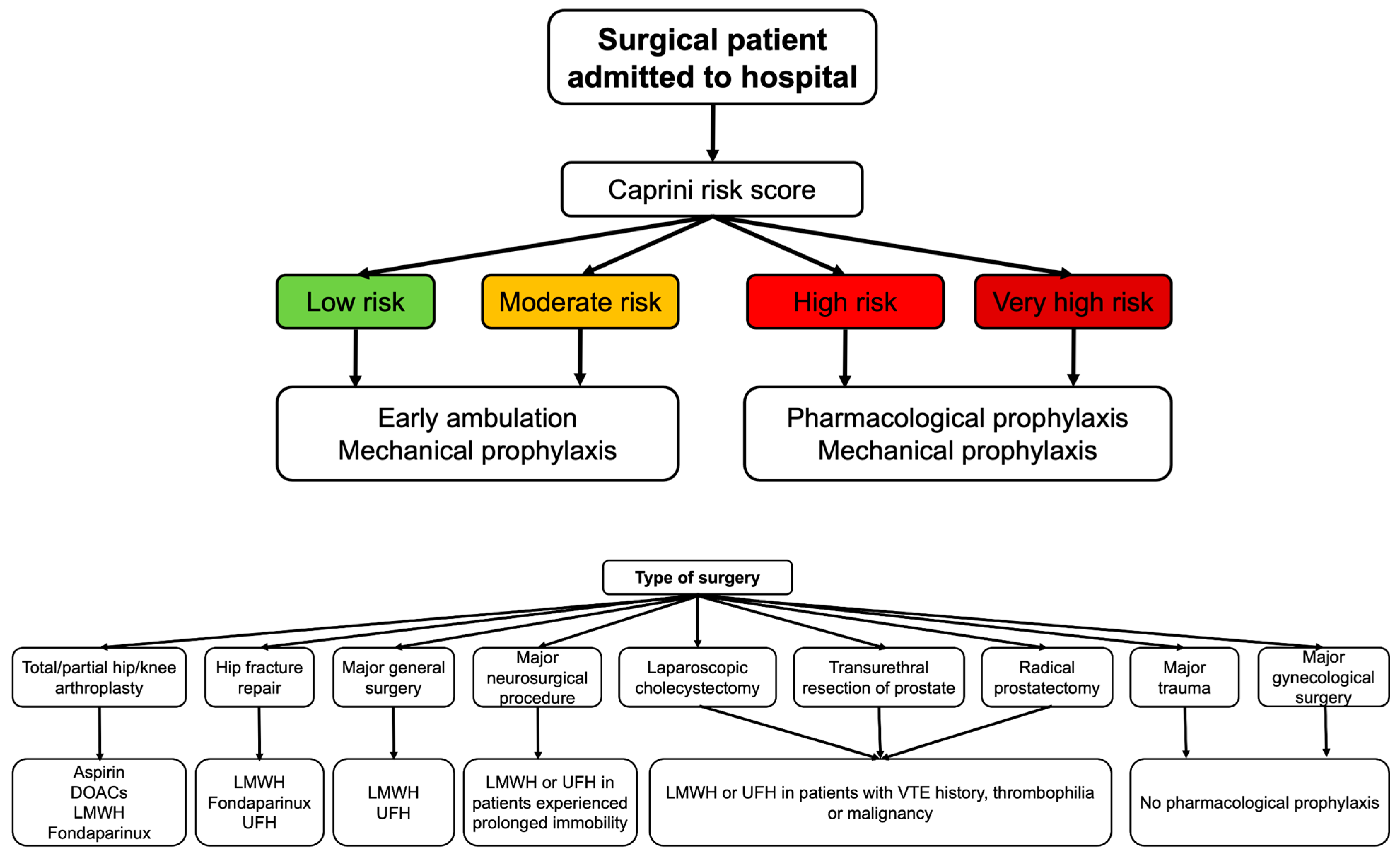

3. VTE and Bleeding Risk Stratification

4. Recommendations in Specific Clinical Conditions

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lutsey, P.L.; Zakai, N.A. Epidemiology and prevention of venous thromboembolism. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pastori, D.; Cormaci, V.M.; Marucci, S.; Franchino, G.; Del Sole, F.; Capozza, A.; Fallarino, A.; Corso, C.; Valeriani, E.; Menichelli, D.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism: From Epidemiology to Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Tritschler, T.; Kahn, S.R.; Rodger, M.A. Venous thromboembolism. Lancet 2021, 398, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan Bruno, X.; Koh, I.; Lutsey, P.L.; Walker, R.F.; Roetker, N.S.; Wilkinson, K.; Smith, N.L.; Plante, T.B.; Repp, A.B.; Holmes, C.E.; et al. Venous thrombosis risk during and after medical and surgical hospitalizations: The medical inpatient thrombosis and hemostasis (MITH) study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 20, 1645–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samama, M.M.; Cohen, A.T.; Darmon, J.Y.; Desjardins, L.; Eldor, A.; Janbon, C.; Leizorovicz, A.; Nguyen, H.; Olsson, C.G.; Turpie, A.G.; et al. A comparison of enoxaparin with placebo for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. Prophylaxis in Medical Patients with Enoxaparin Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leizorovicz, A.; Cohen, A.T.; Turpie, A.G.; Olsson, C.G.; Vaitkus, P.T.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Group, P.M.T.S. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of dalteparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. Circulation 2004, 110, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.T.; Davidson, B.L.; Gallus, A.S.; Lassen, M.R.; Prins, M.H.; Tomkowski, W.; Turpie, A.G.; Egberts, J.F.; Lensing, A.W.; Investigators, A. Efficacy and safety of fondaparinux for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in older acute medical patients: Randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2006, 332, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldhaber, S.Z.; Leizorovicz, A.; Kakkar, A.K.; Haas, S.K.; Merli, G.; Knabb, R.M.; Weitz, J.I.; Investigators, A.T. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2167–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.T.; Spiro, T.E.; Spyropoulos, A.C.; Committee, M.S. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1945–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.T.; Harrington, R.A.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Hull, R.D.; Wiens, B.L.; Gold, A.; Hernandez, A.F.; Gibson, C.M.; Investigators, A. Extended Thromboprophylaxis with Betrixaban in Acutely Ill Medical Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djulbegovic, B.; Boylan, A.; Kolo, S.; Scheurer, D.B.; Anuskiewicz, S.; Khaledi, F.; Youkhana, K.; Madgwick, S.; Maharjan, N.; Hozo, I. Converting IMPROVE bleeding and VTE risk assessment models into a fast-and-frugal decision tree for optimal hospital VTE prophylaxis. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 3214–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunemann, H.J.; Cushman, M.; Burnett, A.E.; Kahn, S.R.; Beyer-Westendorf, J.; Spencer, F.A.; Rezende, S.M.; Zakai, N.A.; Bauer, K.A.; Dentali, F.; et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 3198–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, B.; Darbellay Farhoumand, P.; Pulver, D.; Kopp, B.; Choffat, D.; Tritschler, T.; Vollenweider, P.; Reny, J.L.; Rodondi, N.; Aujesky, D.; et al. Overuse and underuse of thromboprophylaxis in medical inpatients. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 7, 102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikdeli, B.; Sharif-Kashani, B.; Raeissi, S.; Ehteshami-Afshar, S.; Behzadnia, N.; Masjedi, M.R. Chest physicians’ knowledge of appropriate thromboprophylaxis: Insights from the PROMOTE study. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2011, 22, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nendaz, M.R.; Chopard, P.; Lovis, C.; Kucher, N.; Asmis, L.M.; Dorffler, J.; Spirk, D.; Bounameaux, H. Adequacy of venous thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients (IMPART): Multisite comparison of different clinical decision support systems. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 1230–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Vittinghoff, E.; Maselli, J.; Auerbach, A. Unintended consequences of a standard admission order set on venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and patient outcomes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, S.; Wijaya, K.; Rogers, M.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M.; Wojnar, R. A clinical decision support tool for improving venous thromboembolism risk assessment and thromboprophylaxis prescribing compliance within an electronic medication management system: A retrospective observational study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2025, 47, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.T.; Spiro, T.E.; Spyropoulos, A.C.; Desanctis, Y.H.; Homering, M.; Buller, H.R.; Haskell, L.; Hu, D.; Hull, R.; Mebazaa, A.; et al. D-dimer as a predictor of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill, hospitalized patients: A subanalysis of the randomized controlled MAGELLAN trial. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.M.; Spyropoulos, A.C.; Cohen, A.T.; Hull, R.D.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Yusen, R.D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Korjian, S.; Daaboul, Y.; Gold, A.; et al. The IMPROVEDD VTE Risk Score: Incorporation of D-Dimer into the IMPROVE Score to Improve Venous Thromboembolism Risk Stratification. TH Open 2017, 1, e56–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.; Peterson, E.; Lee, A.Y.Y.; de Wit, C.; Carrier, M.; Polley, G.; Tien, J.; Wu, C. Risk stratification for the development of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with cancer. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, P.K.; Kahn, S.R.; Pannucci, C.J.; Secemksy, E.A.; Evans, N.S.; Khorana, A.A.; Creager, M.A.; Pradhan, A.D.; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee. Call to Action to Prevent Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Patients: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e914–e931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprini, J.A.; Tapson, V.F.; Hyers, T.M.; Waldo, A.L.; Wittkowsky, A.K.; Friedman, R.; Colgan, K.J.; Shillington, A.C.; Committee, N.S. Treatment of venous thromboembolism: Adherence to guidelines and impact of physician knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. J. Vasc. Surg. 2005, 42, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decousus, H.; Tapson, V.F.; Bergmann, J.F.; Chong, B.H.; Froehlich, J.B.; Kakkar, A.K.; Merli, G.J.; Monreal, M.; Nakamura, M.; Pavanello, R.; et al. Factors at admission associated with bleeding risk in medical patients: Findings from the IMPROVE investigators. Chest 2011, 139, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreijer, A.R.; Diepstraten, J.; Brouwer, R.; Croles, F.N.; Kragten, E.; Leebeek, F.W.G.; Kruip, M.; van den Bemt, P. Risk of bleeding in hospitalized patients on anticoagulant therapy: Prevalence and potential risk factors. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 62, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, E. The Benefits and Imperative of Venous Thromboembolism Risk Screening for Hospitalized Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, O.; Sengupta, N.; Dysinger, A.; Wang, L. Thromboembolism prophylaxis in medical inpatients: Effect on outcomes and costs. Am. J. Manag. Care 2012, 18, 294–302. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.; Goodacre, S.; Horner, D.; Pandor, A.; Holland, M.; de Wit, K.; Hunt, B.J.; Griffin, X.L. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis for medical inpatients: Decision analysis modelling study. BMJ Med. 2024, 3, e000408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, J.; Abdel Rahman, A.; Kahale, L.; Dempster, M.; Adair, P. Prevention of health care associated venous thromboembolism through implementing VTE prevention clinical practice guidelines in hospitalized medical patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.Y.; Dinatolo, E.; Metra, M.; Sbolli, M.; Dasseni, N.; Butler, J.; Greenberg, B.H. Thromboembolism in Heart Failure Patients in Sinus Rhythm: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Trials, and Future Direction. JACC Heart Fail. 2021, 9, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, M.D.; Geraci, J.M.; Knowlton, A.A. Congestive heart failure and outpatient risk of venous thromboembolism: A retrospective, case-control study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, R.S.; Hellkamp, A.S.; Halperin, J.L.; Poole, J.; Anderson, J.; Johnson, G.; Mark, D.B.; Lee, K.L.; Bardy, G.H.; Investigators, S.C.-H. Risk of thromboembolism in heart failure: An analysis from the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT). Circulation 2007, 115, 2637–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.M.; Tsai, F.; Khatri, N.; Barakat, M.N.; Elkayam, U. Venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with heart failure: Incidence, prognosis, and prevention. Circ. Heart Fail. 2010, 3, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patell, R.; Zwicker, J.I. Inpatient prophylaxis in cancer patients: Where is the evidence? Thromb. Res. 2020, 191, S85–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, A.; Ay, C.; Di Nisio, M.; Gerotziafas, G.; Jara-Palomares, L.; Langer, F.; Lecumberri, R.; Mandala, M.; Maraveyas, A.; Pabinger, I.; et al. Venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, N.S.; Khorana, A.A.; Kuderer, N.M.; Bohlke, K.; Lee, A.Y.Y.; Arcelus, J.I.; Wong, S.L.; Balaban, E.P.; Flowers, C.R.; Gates, L.E.; et al. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3063–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, G.H.; Carrier, M.; Ay, C.; Di Nisio, M.; Hicks, L.K.; Khorana, A.A.; Leavitt, A.D.; Lee, A.Y.Y.; Macbeth, F.; Morgan, R.L.; et al. American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Prevention and treatment in patients with cancer. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 927–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.T.; Tapson, V.F.; Bergmann, J.F.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Kakkar, A.K.; Deslandes, B.; Huang, W.; Zayaruzny, M.; Emery, L.; Anderson, F.A., Jr.; et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): A multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet 2008, 371, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exposito-Ruiz, M.; Arcelus, J.I.; Caprini, J.A.; Lopez-Espada, C.; Bura-Riviere, A.; Amado, C.; Loring, M.; Mastroiacovo, D.; Monreal, M.; Investigators, R. Timing and characteristics of venous thromboembolism after noncancer surgery. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2021, 9, 859–867 e852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.R.; Morgano, G.P.; Bennett, C.; Dentali, F.; Francis, C.W.; Garcia, D.A.; Kahn, S.R.; Rahman, M.; Rajasekhar, A.; Rogers, F.B.; et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 3898–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Al-Horani, R.A. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis in Major Orthopedic Surgeries and Factor XIa Inhibitors. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Han, L.; Wang, Y.; Kang, F.; Cai, F.; Wu, L.; Zheng, X.; Li, L.; Dong, L.E.; Dong, L.; et al. Unlocking the potential of fondaparinux: Guideline for optimal usage and clinical suggestions (2023). Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1352982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinde, L.B.; Smabrekke, B.; Mathiesen, E.B.; Lochen, M.L.; Njolstad, I.; Hald, E.M.; Wilsgaard, T.; Braekkan, S.K.; Hansen, J.B. Ischemic Stroke and Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in the General Population: The Tromso Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, A.S.; Sheth, K.N. Hemorrhagic Conversion of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.; Caso, V.; Kappelle, L.J.; Pavlovic, A.; Sandercock, P.; European Stroke, O. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines for prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in immobile patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Eur. Stroke J. 2016, 1, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, C.T.; Ramanathan, R.S.; Malhotra, K.; Quigley, M.R.; Kelly, K.M.; Tian, M.; Protetch, J.; Wong, C.; Wright, D.G.; Tayal, A.H. Safety of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with fondaparinux in ischemic stroke. Thromb. Res. 2015, 135, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.N.; Fazen, L.E.; Wendell, L.; Chang, Y.; Rost, N.S.; Snider, R.; Schwab, K.; Chanderraj, R.; Kabrhel, C.; Kinnecom, C.; et al. Risk of thromboembolism following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit. Care 2009, 10, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raslan, A.M.; Fields, J.D.; Bhardwaj, A. Prophylaxis for venous thrombo-embolism in neurocritical care: A critical appraisal. Neurocrit. Care 2010, 12, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, S.M.; Ziai, W.C.; Cordonnier, C.; Dowlatshahi, D.; Francis, B.; Goldstein, J.N.; Hemphill, J.C., 3rd; Johnson, R.; Keigher, K.M.; Mack, W.J.; et al. 2022 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2022, 53, e282–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, D.; Sato, R.; Lee, Y.I.; Wang, H.Y.; Nishida, K.; Steiger, D. The prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of acute pulmonary embolism complicating sepsis and septic shock: A national inpatient sample analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Gao, S.; Pan, W.; Chen, J.; Su, L.; He, H.; Long, Y.; Yin, C.; et al. Factors influencing DVT formation in sepsis. Thromb. J. 2024, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; McIntyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, e1063–e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Irish, A.B.; Watts, G.F.; Oostryck, R.; Dogra, G.K. Hypercoagulability in chronic kidney disease is associated with coagulation activation but not endothelial function. Thromb. Res. 2008, 123, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanakit, K.; Cushman, M.; Stehman-Breen, C.; Heckbert, S.R.; Folsom, A.R. Chronic kidney disease increases risk for venous thromboembolism. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahady, S.E.; Polekhina, G.; Woods, R.L.; Wolfe, R.; Wetmore, J.B.; Margolis, K.L.; Wood, E.M.; Cloud, G.C.; Murray, A.M.; Polkinghorne, K.R. Association Between CKD and Major Hemorrhage in Older Persons: Data From the Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly Randomized Trial. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Guideline Centre (UK). Venous Thromboembolism in Over 16s: Reducing the Risk of Hospital-Acquired Deep Vein Thrombosis or Pulmonary Embolism; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2018. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29697228/ (accessed on 1 December 2025). [PubMed]

- Pandor, A.; Tonkins, M.; Goodacre, S.; Sworn, K.; Clowes, M.; Griffin, X.L.; Holland, M.; Hunt, B.J.; de Wit, K.; Horner, D. Risk assessment models for venous thromboembolism in hospitalised adult patients: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.C.; Wang, J.K.; Sharp, C.; Chen, J.H. When order sets do not align with clinician workflow: Assessing practice patterns in the electronic health record. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2019, 28, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleyer, A.M.; Schreuder, A.B.; Jarman, K.M.; Logerfo, J.P.; Goss, J.R. Adherence to guideline-directed venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among medical and surgical inpatients at 33 academic medical centers in the United States. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2011, 26, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MEDENOX [5], 1999 | PREVENT [6], 2004 | ARTEMIS [7], 2006 | ADOPT [8], 2011 | MAGELLAN [9], 2013 | APEX [10], 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 1102 | 3706 | 849 | 6528 | 8101 | 7513 |

| Age (years) | >40 | >40 | >60 | >40 | >40 | >40 |

| Anticoagulant | Enoxaparin 20 mg or 40 mg for 7 days | Dalteparin 5000 IU for 14 days | Fondaparinux 2.5 mg for 6–14 days | Apixaban 2.5 mg for 30 days | Rivaroxaban 10 mg for 35 ± 4 days | Betrixaban 80 mg for 35–42 days |

| Comparator | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo | Enoxaparin 40 mg for 6–14 days | Enoxaparin 40 mg for 10 ± 4 days | Enoxaparin 40 mg for 10 ± 4 days |

| Follow-up | 14 days | 90 days | 30 days | 30 days | 35 ± 4 days | 47 days |

| Outcomes | VTE risk (5.5% vs. 14.9%) RR 0.37 (95%CI: 0.21–0.64) | VTE/sudden death risk (2.77% vs. 4.96%) RR: 0.55 (95%CI: 0.38–0.80) | VTE risk (5.6% vs. 10.5%) RR: 0.54 (95%CI: 0.31–0.92) | No superiority (2.71% vs. 3.05%) RR: 0.87 (95%CI: 0.62–1.23) | VTE risk (4.4% vs. 5.7%) RR: 0.77 (95%CI: 0.62–0.96) | VTE risk (5.3% vs. 7%) RR: 0.76 (95%CI: 0.63–0.92) |

| VTE Risk Score | Population | Risk Determinants | VTE Prophylaxis Eligibility Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Padua VTE RAM | Acutely ill medical inpatients | Active cancer, previous VTE, reduced mobility, thrombophilia, recent trauma/surgery, elderly age, heart/respiratory failure, acute MI/stroke, acute infection/rheumatologic disorder, obesity, hormone therapy | ≥4: high risk |

| IMPROVE VTE RAM | Acutely ill medical inpatients | Previous VTE, known thrombophilia, active cancer, immobilization ≥ 7 days, ICU/CCU admission, age > 60, lower-limb paralysis | ≥2: high risk |

| IMPROVE-DD VTE Score | Acutely ill medical inpatients | Same as IMPROVE + elevated D-dimer (≥2× ULN) | ≥2: high risk |

| Khorana Score | Oncology patients | Cancer type, platelet count, hemoglobin or RBC growth factors use, leukocyte count, BMI ≥ 35 | 0: low risk 1–2: intermediate risk ≥3: high risk |

| Caprini VTE Score | Surgical patients | 40 distinct individual VTE risk factors including age, BMI > 25, cancer, history of VTE, thrombophilia, immobilization, surgery type, pregnancy, hormonal therapy, varicose veins, edema, inflammatory conditions | 0–1: low risk 2: moderate risk 3–4: high risk ≥5: very high risk |

| Predictor | Points |

|---|---|

| Active gastric or duodenal ulcer | 4.5 |

| History of bleeding within 3 months before admission | 4 |

| Platelet count < 50 × 109/L | 4 |

| Age 40–84 years | 1.5 |

| Age ≥ 85 years | 3.5 |

| Hepatic failure (INR > 1.5) | 2.5 |

| Moderate renal failure (GFR 30–59 mL/min) | 1 |

| Severe renal failure (GFR < 30 mL/min) | 2.5 |

| ICU or CCU admission | 2.5 |

| Central venous catheter placement | 2 |

| Rheumatic disease | 2 |

| Active cancer | 2 |

| Male sex | 1 |

| Clinical Condition | Recommended Thromboprophylaxis Regimens |

|---|---|

| Heart failure [32,33] | LMWH, fondaparinux, or low-dose UFH |

| Cancer [35,36,37] | LMWH, fondaparinux, or UFH |

| Major general surgery [40] | LMWH or UFH |

| Hip or knee arthroplasty [40,42] | LMWH, fondaparinux, DOACs, or aspirin |

| Hip fracture repair [40,42] | LMWH, fondaparinux, UFH |

| Major neurosurgery [40] | LMWH preferred over UFH |

| Acute ischemic stroke [45,46] | Intermittent pneumatic compression + LMWH, UFH, fondaparinux or heparinoid |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage [49] | Intermittent pneumatic compression + low-dose UFH or LMWH |

| Sepsis/septic shock [52] | LMWH preferred over UFH |

| Chronic kidney disease [56] | LMWH or UFH (dose-adjusted) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Velliou, M.; Bistola, V.; Parissis, J.; Polyzogopoulou, E. Current Trends in Venous Thromboprophylaxis for Inpatient Care. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010018

Velliou M, Bistola V, Parissis J, Polyzogopoulou E. Current Trends in Venous Thromboprophylaxis for Inpatient Care. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelliou, Maria, Vasiliki Bistola, John Parissis, and Effie Polyzogopoulou. 2026. "Current Trends in Venous Thromboprophylaxis for Inpatient Care" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010018

APA StyleVelliou, M., Bistola, V., Parissis, J., & Polyzogopoulou, E. (2026). Current Trends in Venous Thromboprophylaxis for Inpatient Care. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010018