Treatment-Free Survival and the Pattern of Follow-Up Treatments After Curative Prostate Cancer Treatment, a Real-World Analysis of Big Data from Electronic Health Records from a Tertiary Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Patient Identification and Classification

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.5.1. Treatment-Free Survival

2.5.2. Statistical Analysis

2.5.3. Medication Categorization and Analysis

2.6. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

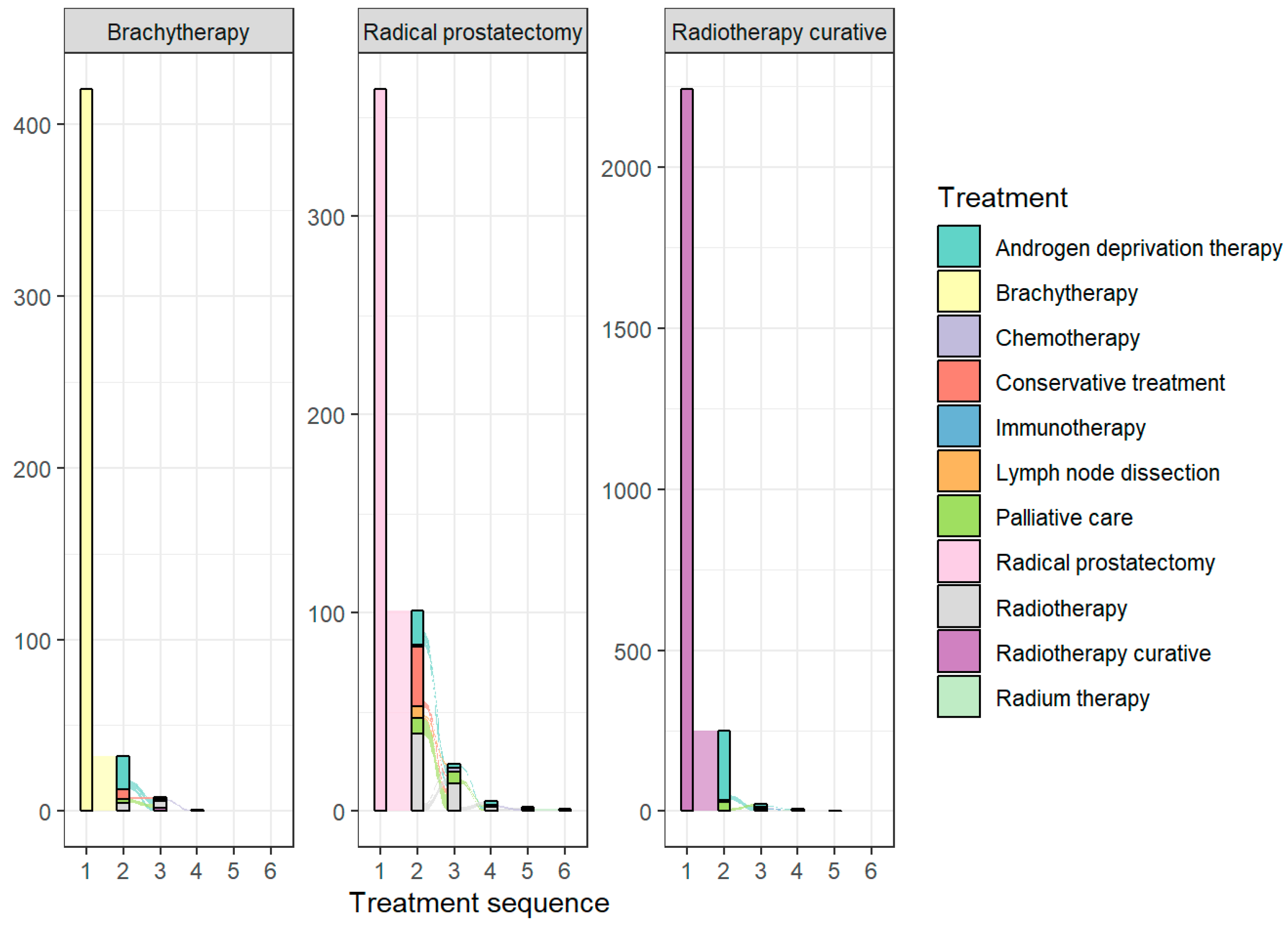

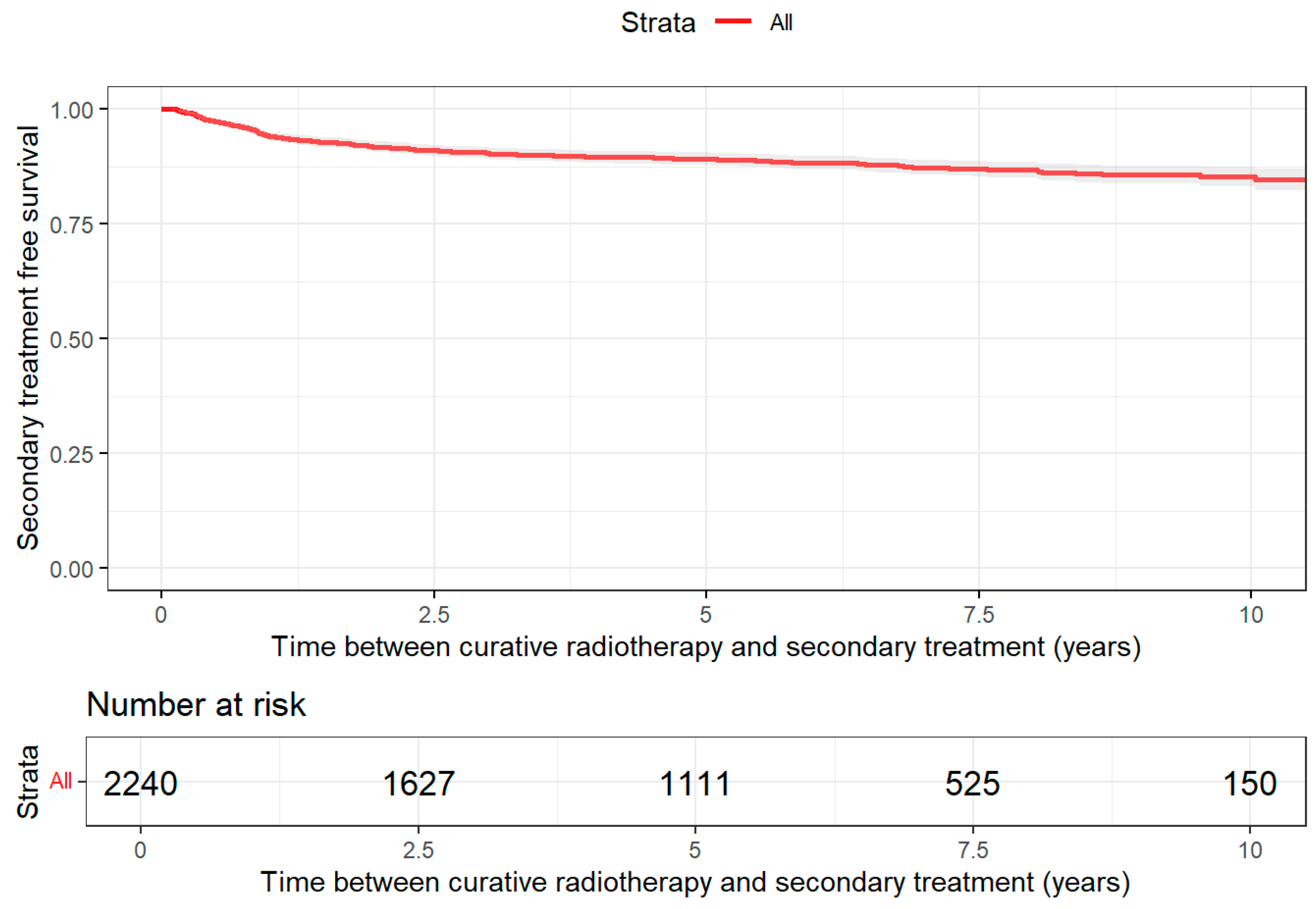

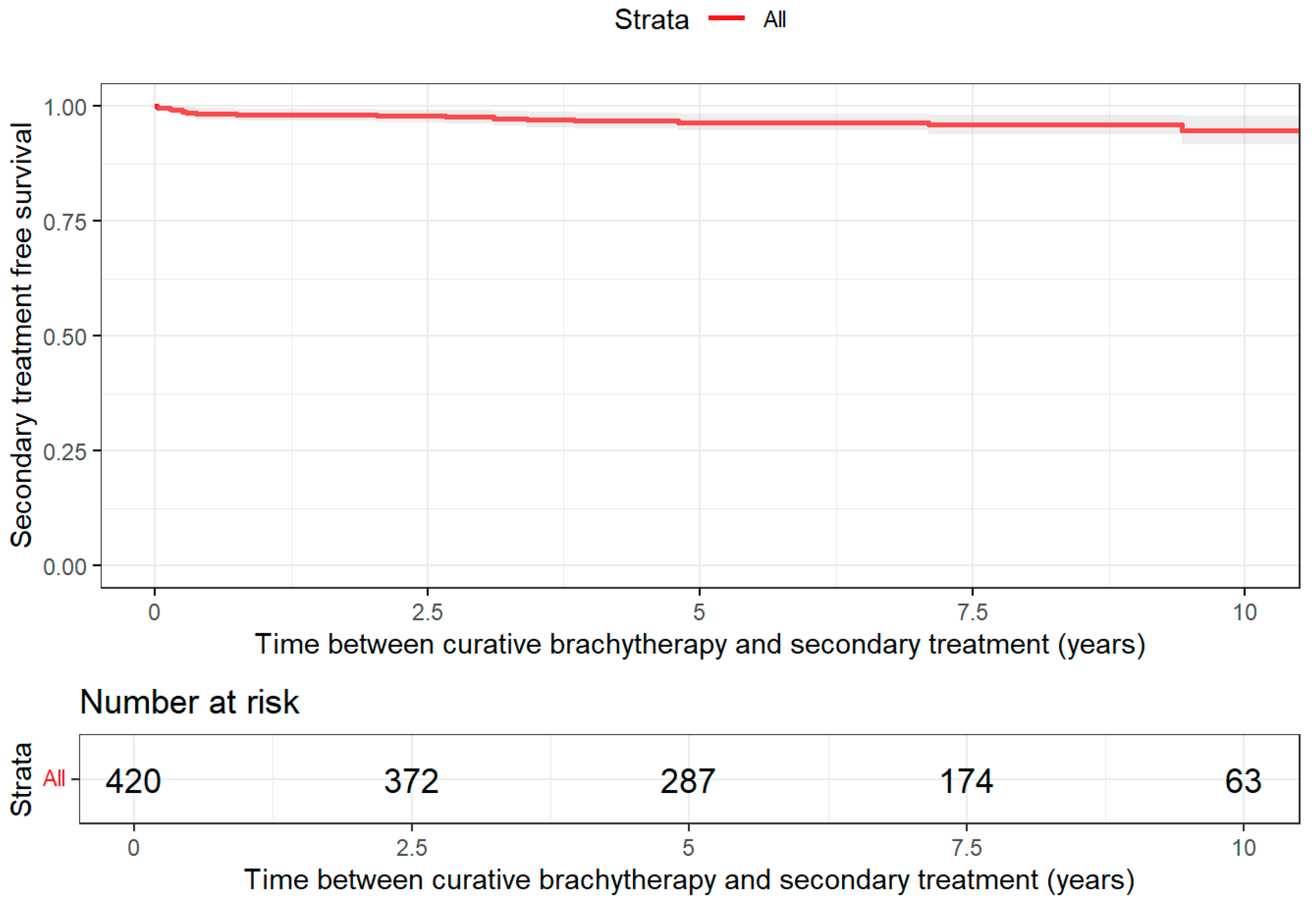

3.2. Treatment Patterns

3.3. Medication Use and Changes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCa | Prostate cancer |

| RWD | Real-world data |

| EHR | Electronic health records |

| EFS | Event-free Survival |

| TFS | Treatment-free survival |

| RP | Radical prostatectomy |

| BT | Brachytherapy |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| cRT | Curative radiotherapy |

| ADT | Androgen deprivation therapy |

| CTX | Chemotherapy |

| LND | Lymph node dissection |

| RdT | Radium therapy |

| RMST | Restricted mean survival time |

| PSA | Prostate-specific antigen |

| ISUP GG | International Society of Urological Pathology Grade Group |

| TNM | Tumor/Node/Metastasis |

| DTC | Diagnosis Treatment Combination |

| ATC | Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system |

| FU | Follow-up |

| PCSM | Prostate cancer-specific mortality |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| SIOG | International Society of Geriatric Oncology |

| PRIAS | Prostate Cancer Research International Active Surveillance |

| ERSPC | European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer |

| PIONEER | Prostate Cancer DIagnOsis and TreatmeNt Enhancement through the Power of Big Data in EuRope |

References

- Cornford, P.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Van den Broeck, T.; Brunckhorst, O.; Darraugh, J.; Eberli, D.; De Meerleer, G.; De Santis, M.; Farolfi, A.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer—2024 Update. Part I: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasalic, D.; Kuban, D.A.; Allen, P.K.; Tang, C.; Mesko, S.M.; Grant, S.R.; Augustyn, A.A.; Frank, S.J.; Choi, S.; Hoffman, K.E.; et al. Dose Escalation for Prostate Adenocarcinoma: A Long-Term Update on the Outcomes of a Phase 3, Single Institution Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 104, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, J.M.; Moughan, J.; Purdy, J.; Bosch, W.; Bruner, D.W.; Bahary, J.-P.; Lau, H.; Duclos, M.; Parliament, M.; Morton, G.; et al. Effect of Standard vs Dose-Escalated Radiation Therapy for Patients With Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer: The NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, e180039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemsbergen, W.D.; Al-Mamgani, A.; Slot, A.; Dielwart, M.F.H.; Lebesque, J.V. Long-term results of the Dutch randomized prostate cancer trial: Impact of dose-escalation on local, biochemical, clinical failure, and survival. Radiother. Oncol. 2014, 110, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill-Axelson, A.; Holmberg, L.; Garmo, H.; Rider, J.R.; Taari, K.; Busch, C.; Nordling, S.; Häggman, M.; Andersson, S.O.; Spångberg, A.; et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariton, E.; Locascio, J.J. Randomised controlled trials—The gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. BJOG 2018, 125, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmberg, L.; Garmo, H.; Andersson, S.O.; Andrén, O.; Johansson, E.; Taari, K.; Häggman, M.; Nordling, S.; Adami, H.O.; Bill-Axelson, A. Time Dependence of Outcomes in the SPCG-4 Randomized Trial Comparing Radical Prostatectomy and Watchful Waiting in Early Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2025, 88, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engesser, C.; Henkel, M.; Alargkof, V.; Fassbind, S.; Studer, J.; Engesser, J.; Walter, M.; Elyan, A.; Dugas, S.; Trotsenko, P.; et al. Clinical decision making in prostate cancer care—Evaluation of EAU-guidelines use and novel decision support software. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batko, K.; Ślęzak, A. The use of Big Data Analytics in healthcare. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.I.; MacLennan, S.; Ribal, M.J.; Roobol, M.J.; Dimitropoulos, K.; van den Broeck, T.; MacLennan, S.J.; Axelsson, S.E.; Gandaglia, G.; Willemse, P.P.; et al. Unanswered questions in prostate cancer—Findings of an international multi-stakeholder consensus by the PIONEER consortium. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2023, 20, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedeborg, R.; Sund, M.; Lambe, M.; Plym, A.; Fredriksson, I.; Syrjä, J.; Holmberg, L.; Robinson, D.; Stattin, P.; Garmo, H. An Aggregated Comorbidity Measure Based on History of Filled Drug Prescriptions: Development and Evaluation in Two Separate Cohorts. Epidemiology 2021, 32, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oostrom, S.H.; Picavet, H.S.; van Gelder, B.M.; Lemmens, L.C.; Hoeymans, N.; van Dijk, C.E.; Verheij, R.A.; Schellevis, F.G.; Baan, C.A. Multimorbidity and comorbidity in the Dutch population – data from general practices. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.L.; O’Connell, D.L.; Goldsbury, D.E.; Weber, M.F.; Smith, D.P.; Barton, M.B. Patterns of care for men with prostate cancer: The 45 and Up Study. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 214, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucki, M.; Dosch, S.; Gnädinger, M.; Graber, S.M.; Huber, C.A.; Lenzin, G.; Strebel, R.T.; Zwahlen, D.R.; Omlin, A.; Wieser, S. Real-world treatment patterns and medical costs of prostate cancer patients in Switzerland—A claims data analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 204, 114072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, K.; Straten, V.; Remmers, S.; MacLennan, S.; MacLennan, S.; Gandaglia, G.; Willemse, P.-P.M.; Herrera, R.; Omar, M.I.; Russell, B.; et al. Secondary Treatment for Men with Localized Prostate Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of PRIAS and ERSPC-Rotterdam Data within the PIONEER Data Platform. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.J.; Sartor, O.; Miller, K.; Saad, F.; Tombal, B.; Kalinovský, J.; Jiao, X.; Tangirala, K.; Sternberg, C.N.; Higano, C.S. Treatment Patterns and Outcomes in Patients With Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer in a Real-world Clinical Practice Setting in the United States. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2020, 18, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavsar, N.A.; Harrison, M.R.; Scales, C.D.; Zhang, T.; Troy, J.; Ward, K.; Jabusch, S.M.; Lampron, Z.; George, D.J. Design and Rationale of the Outcomes Database to Prospectively Assess the Changing Therapy Landscape in Renal Cell Carcinoma Registry: A Multi-institutional, Prospective Study of Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2024, 66, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, M.; Quirt, J.; Morris, W.J.; So, A.; Sing, C.K.; Pickles, T.; Tyldesley, S. Population-based 10-year event-free survival after radical prostatectomy for patients with prostate cancer in British Columbia. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2015, 9, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, J.F.; Zamora, V.; Garin, O.; Gutiérrez, C.; Pont, À.; Pardo, Y.; Goñi, A.; Mariño, A.; Hervás, A.; Herruzo, I.; et al. Mortality and biochemical recurrence after surgery, brachytherapy, or external radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: A 10-year follow-up cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, F.C.; Donovan, J.L.; Lane, J.A.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Holding, P.; Davis, M.; Peters, T.J.; Turner, E.L.; Martin, R.M.; et al. 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassil, A.D.; Murphy, E.S.; Reddy, C.A.; Angermeier, K.W.; Altman, A.; Chehade, N.; Ulchaker, J.; Klein, E.A.; Ciezki, J.P. Five Year Biochemical Recurrence Free Survival for Intermediate Risk Prostate Cancer After Radical Prostatectomy, External Beam Radiation Therapy or Permanent Seed Implantation. Urology 2010, 76, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AU UroEvidenceHub Launches Prospective Prostate Cancer Data Registry with First Patient Successfully Added. Available online: https://uroweb.org/science-publications/eau-uroevidencehub (accessed on 30 November 2024).

| Characteristic | Brachytherapy N = 420 1 | Radical Prostatectomy N = 364 1 | Radiotherapy Curative N = 2240 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSA (ng/mL) | 9 (6, 16) | 7 (5, 14) | 8 (3, 17) |

| Unknown | 378 | 352 | 2205 |

| Age at diagnosis | 68 (62, 73) | 65 (61, 69) | 72 (68, 76) |

| Gleason score | |||

| 6 | 134 (56%) | 103 (37%) | 252 (23%) |

| 7 | 104 (43%) | 133 (47%) | 504 (46%) |

| 8 | 3 (1.2%) | 29 (10%) | 198 (18%) |

| 9 | 0 (0%) | 15 (5.3%) | 133 (12%) |

| 10 | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 18 (1.6%) |

| Unknown | 179 | 83 | 1135 |

| T stage | |||

| T0 | 4 (1.1%) | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.1%) |

| T1 | 125 (33%) | 36 (13%) | 316 (17%) |

| T2 | 194 (52%) | 127 (46%) | 704 (38%) |

| T3 | 50 (13%) | 102 (37%) | 780 (42%) |

| T4 | 2 (0.5%) | 10 (3.6%) | 56 (3.0%) |

| Unknown | 45 | 87 | 382 |

| N stage | |||

| Nx | 289 (77%) | 191 (69%) | 733 (39%) |

| N0 | 72 (19%) | 48 (17%) | 932 (50%) |

| N+ | 14 (3.7%) | 38 (14%) | 193 (10%) |

| Unknown | 45 | 87 | 382 |

| M stage | |||

| Mx | 288 (77%) | 230 (83%) | 874 (47%) |

| M0 | 85 (23%) | 44 (16%) | 927 (50%) |

| M+ | 2 (0.5%) | 3 (1.1%) | 57 (3.1%) |

| Unknown | 45 | 87 | 382 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Denijs, F.B.; Remmers, S.; Bokhorst, L.P.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Roobol, M.J. Treatment-Free Survival and the Pattern of Follow-Up Treatments After Curative Prostate Cancer Treatment, a Real-World Analysis of Big Data from Electronic Health Records from a Tertiary Center. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010022

Denijs FB, Remmers S, Bokhorst LP, van den Bergh RCN, Roobol MJ. Treatment-Free Survival and the Pattern of Follow-Up Treatments After Curative Prostate Cancer Treatment, a Real-World Analysis of Big Data from Electronic Health Records from a Tertiary Center. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleDenijs, Fréderique B., Sebastiaan Remmers, Leonard P. Bokhorst, Roderick C. N. van den Bergh, and Monique J. Roobol. 2026. "Treatment-Free Survival and the Pattern of Follow-Up Treatments After Curative Prostate Cancer Treatment, a Real-World Analysis of Big Data from Electronic Health Records from a Tertiary Center" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010022

APA StyleDenijs, F. B., Remmers, S., Bokhorst, L. P., van den Bergh, R. C. N., & Roobol, M. J. (2026). Treatment-Free Survival and the Pattern of Follow-Up Treatments After Curative Prostate Cancer Treatment, a Real-World Analysis of Big Data from Electronic Health Records from a Tertiary Center. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010022