Nine-Year Surveillance of Candida Bloodstream Infections in a Southern Italian Tertiary Hospital: Species Distribution, Antifungal Resistance, and Stewardship Implications

Abstract

1. Lay Summary

2. Introduction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Patient Inclusion

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

3.3. Identification of Candida spp. and Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Ethics Statement

4. Results

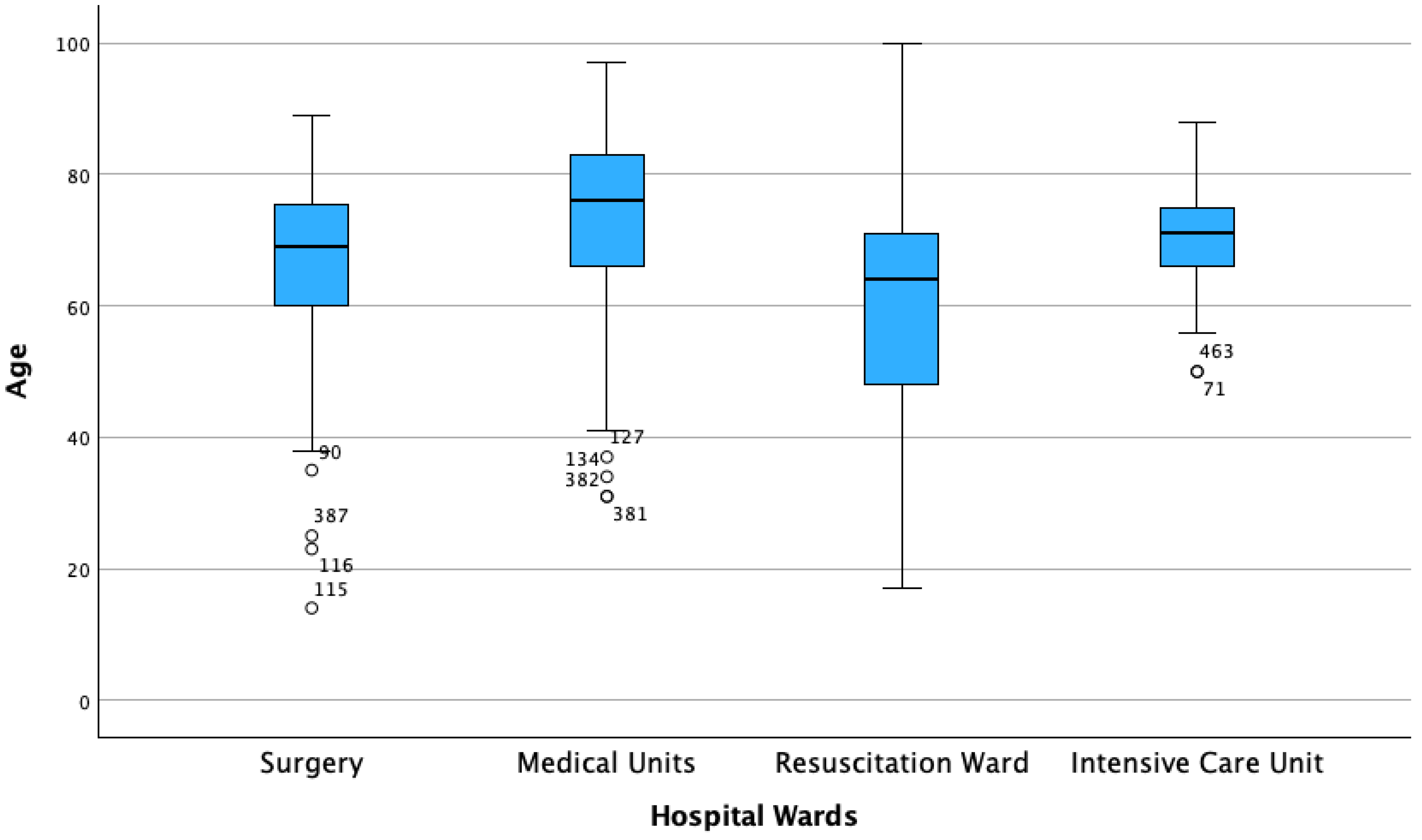

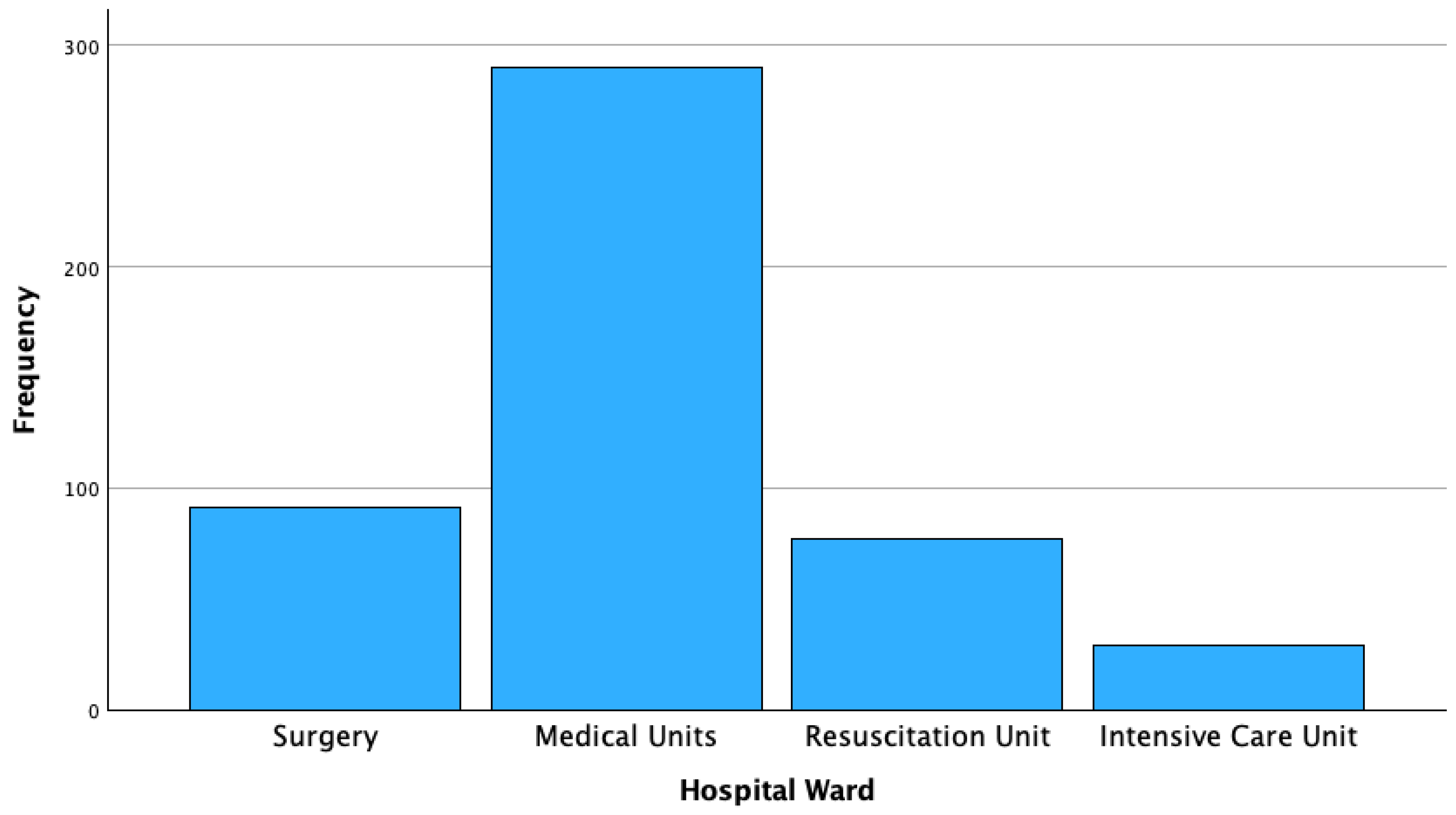

4.1. Patient Characteristics

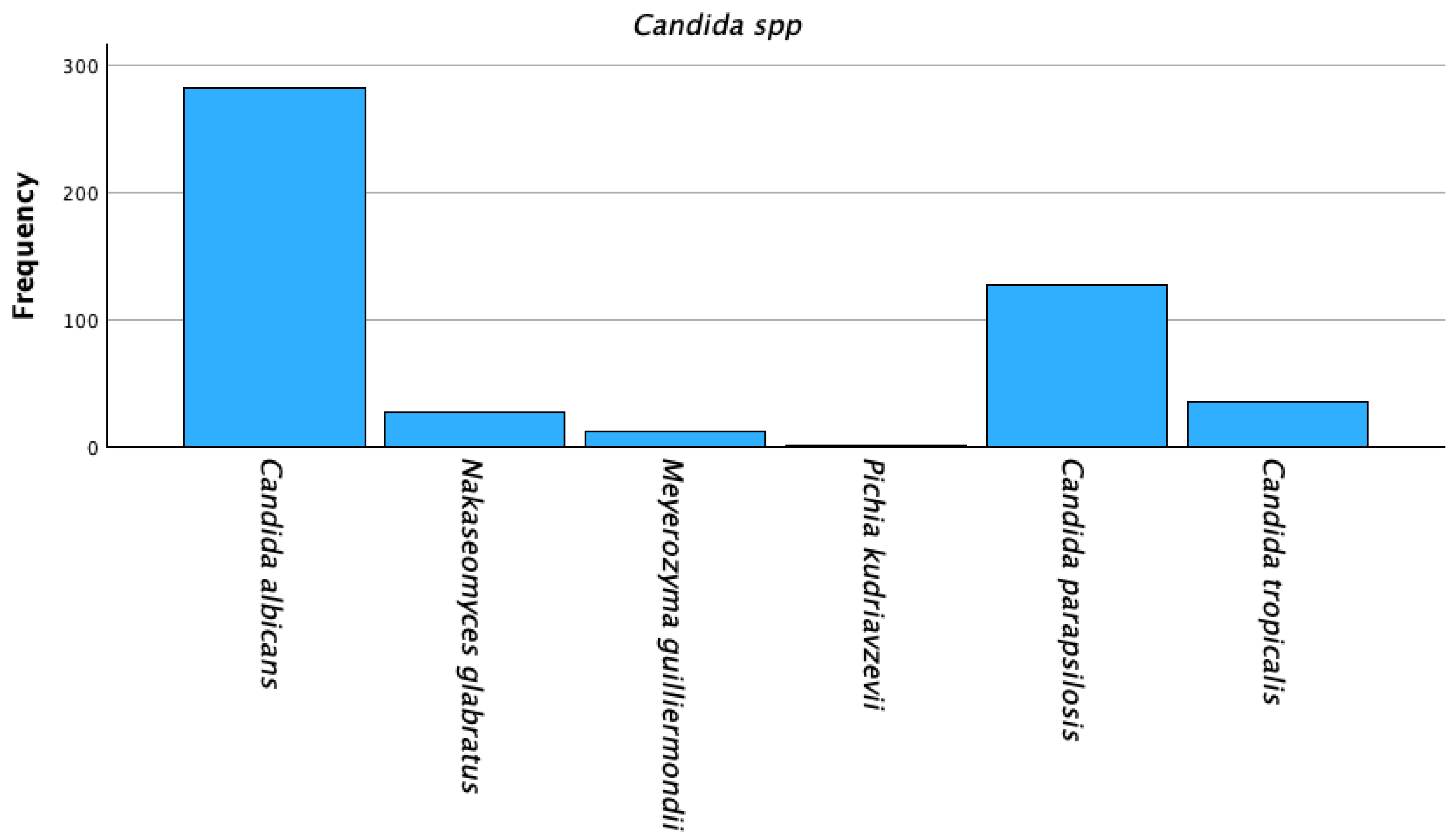

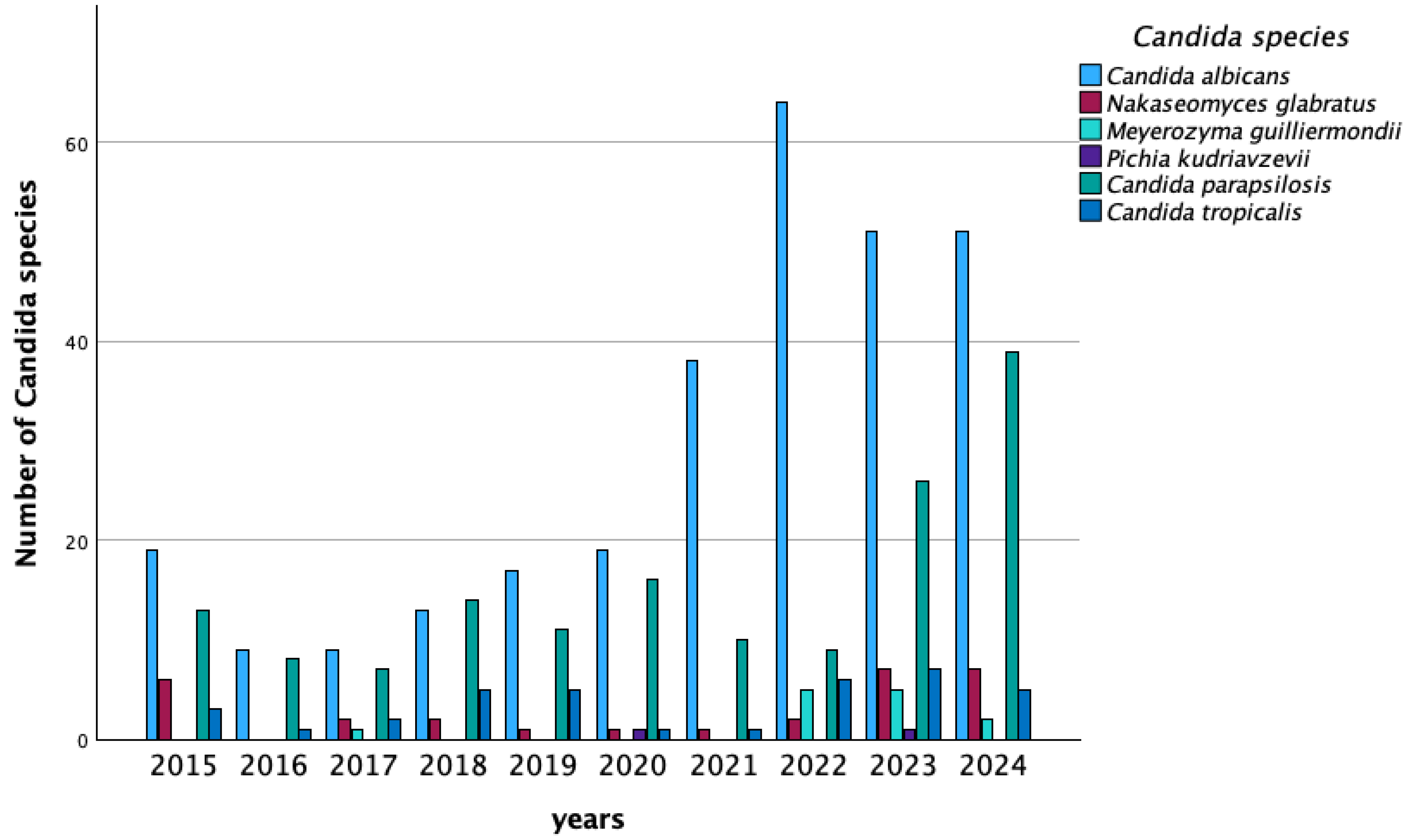

4.2. Candida Species Distribution

4.3. Antifungal Resistance Profiles

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kotey, F.C.; Dayie, N.T.; Tetteh-Uarcoo, P.B.; Donkor, E.S. Candida Bloodstream Infections: Changes in Epidemiology and Increase in Drug Resistance. Infect. Dis. 2021, 14, 11786337211026927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holmes, C.L.; Albin, O.R.; Mobley, H.L.T.; Bachman, M.A. Bloodstream infections: Mechanisms of pathogenesis and opportunities for intervention. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmanton-García, J.; Cornely, O.A.; Stemler, J.; Barać, A.; Steinmann, J.; Siváková, A.; Akalin, E.H.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Loughlin, L.; Toscano, C.; et al. Attributable mortality of candidemia—Results from the ECMM Candida III multinational European Observational Cohort Study. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

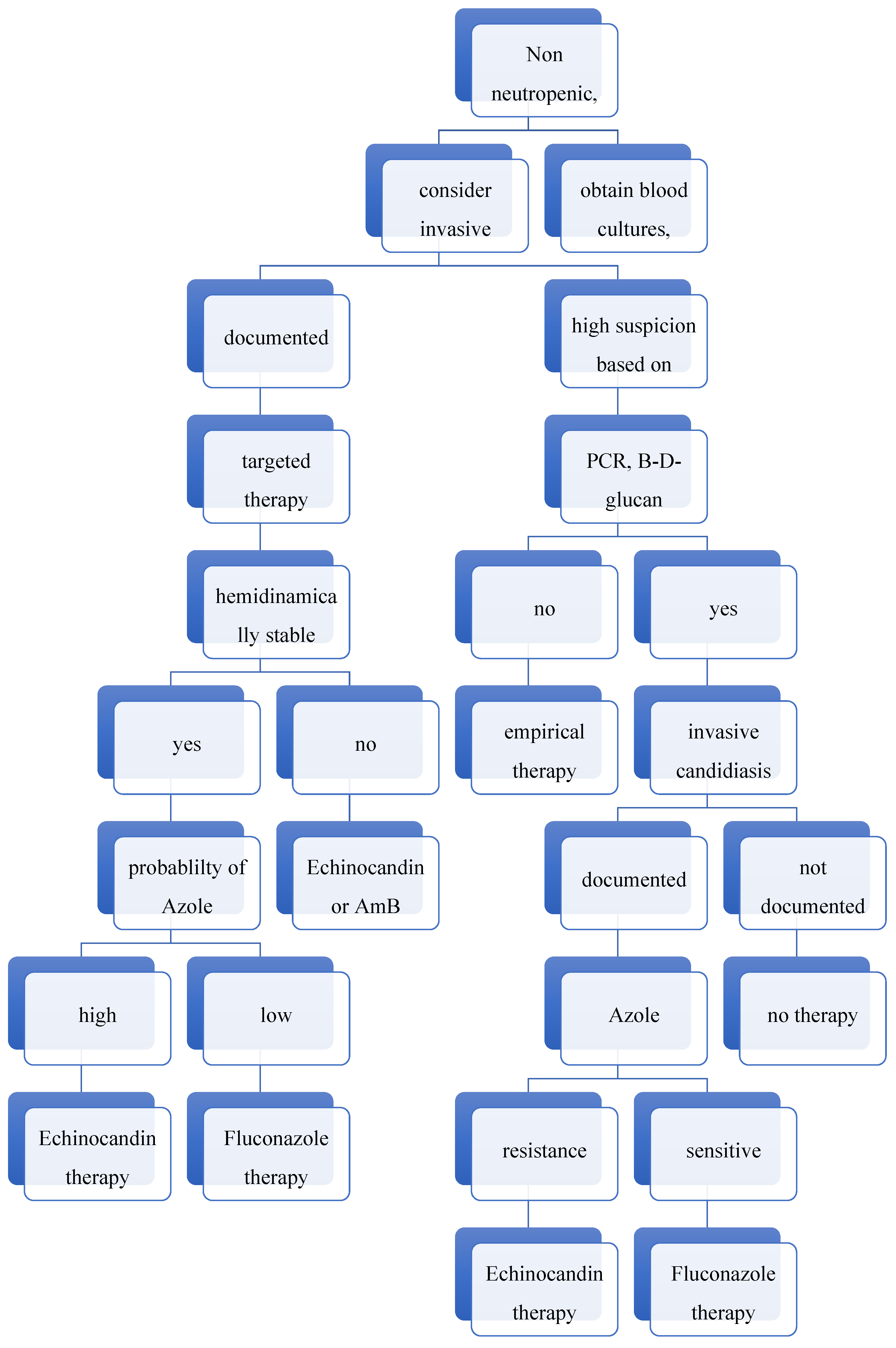

- Azim, A.; Ahmed, A. Diagnosis and management of invasive fungal diseases in non-neutropenic ICU patients, with focus on candidiasis and aspergillosis: A comprehensive review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1256158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thomas-Rüddel, D.O.; Schlattmann, P.; Pletz, M.; Kurzai, O.; Bloos, F. Risk Factors for Invasive Candida Infection in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest 2022, 161, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wan Ismail, W.N.A.; Jasmi, N.; Khan, T.M.; Hong, Y.H.; Neoh, C.F. The Economic Burden of Candidemia and Invasive Candidiasis: A Systematic Review. Value Health Reg. Issues 2020, 21, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortorano, A.M.; Prigitano, A.; Morroni, G.; Brescini, L.; Barchiesi, F. Candidemia: Evolution of Drug Resistance and Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 5543–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oliva, A.; De Rosa, F.G.; Mikulska, M.; Pea, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; Tascini, C.; Venditti, M. Invasive Candida infection: Epidemiology, clinical and therapeutic aspects of an evolving disease and the role of rezafungin. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2023, 21, 957–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornely, F.B.; Cornely, O.A.; Salmanton-García, J.; Koehler, F.C.; Koehler, P.; Seifert, H.; Wingen-Heimann, S.; Mellinghoff, S.C. Attributable mortality of candidemia after introduction of echinocandins. Mycoses 2020, 63, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornely, O.A.; Sprute, R.; Bassetti, M.; Chen, S.C.; Groll, A.H.; Kurzai, O.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Revathi, G. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of candidiasis: An initiative of the ECMM in cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e280–e293, Erratum in Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00154-9. Erratum in Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e261. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00252-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, K.Y.; Chen, Y.Z.; Zhou, Z.L.; Tsai, J.N.; Tseng, M.N.; Liu, H.L.; Wu, C.J.; Liao, Y.C.; Lin, C.C.; Tsai, D.J.; et al. Detection in Orchards of Predominant Azole-Resistant Candida tropicalis Genotype Causing Human Candidemia, Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 2323–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kidd, S.E.; Abdolrasouli, A.; Hagen, F. Fungal Nomenclature: Managing Change is the Name of the Game. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofac559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Srivastava, V.; Singla, R.K.; Dubey, A.K. Emerging Virulence, Drug Resistance and Future Anti-fungal Drugs for Candida Pathogens. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 759–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhani, P.; Patil, A.; Majumdar, S. Challenges in the Polyene- and Azole-Based Pharmacotherapy of Ocular Fungal Infections. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 35, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szymański, M.; Chmielewska, S.; Czyżewska, U.; Malinowska, M.; Tylicki, A. Echinocandins—Structure, mechanism of action and use in antifungal therapy. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 876–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Souza, C.M.; Bezerra, B.T.; Mellon, D.A.; de Oliveira, H.C. The evolution of antifungal therapy: Traditional agents, current challenges and future perspectives. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 8, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Y.; Hind, C.; Furner-Pardoe, J.; Sutton, J.M.; Rahman, K.M. Understanding the mechanisms of resistance to azole antifungals in Candida species. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bohner, F.; Papp, C.; Gácser, A. The effect of antifungal resistance development on the virulence of Candida species. FEMS Yeast Res. 2022, 22, foac019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vannini, M.; Emery, S.; Lieutier-Colas, F.; Legueult, K.; Mondain, V.; Retur, N.; Gastaud, L.; Pomares, C.; Hasseine, L. Epidemiology of candidemia in NICE area, France: A five-year study of antifungal susceptibility and mortality. J. Mycol. Med. 2022, 32, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J. Progress in antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida spp. by use of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods, 2010 to 2012. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 2846–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Messer, S.A.; Woosley, L.N.; Jones, R.N.; Castanheira, M. Echinocandin and triazole antifungal susceptibility profiles for clinical opportunistic yeast and mold isolates collected from 2010 to 2011: Application of new CLSI clinical breakpoints and epidemiological cutoff values for characterization of geographic and temporal trends of antifungal resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 2571–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsipoulaki, M.; Stappers, M.H.T.; Malavia-Jones, D.; Brunke, S.; Hube, B.; Gow, N.A.R. Candida albicans and Candida glabrata: Global priority pathogens. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2024, 88, e0002123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoenigl, M.; Salmanton-García, J.; Egger, M.; Gangneux, J.-P.; Bicanic, T.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Klimko, N.; Barac, A.; Özenci, V.; et al. Guideline adherence and survival of patients with candidaemia in Europe: Results from the ECMM Candida III multinational European observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano-Martín, A.; Escribano, P.; Machado, M.; Guinea, J.; Reigadas, E.; García-Clemente, P.; Bouza, E.; Muñoz, P. Trends in Candidemia Over the Last 14 Years: A Comparative Analysis of Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salari, S.; Khosravi, A.R.; Mousavi, S.A.; Nikbakht-Brojeni, G.H. Mechanisms of resistance to fluconazole in Candida albicans clinical isolates from Iranian HIV-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. J. Mycol. Medicale. 2016, 26, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyvanfar, A.; Najafiarab, H.; Talebian, N.; Tafti, M.F.; Adeli, G.; Ghasemi, Z.; Tehrani, S. Drug-resistant oral candidiasis in patients with HIV infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Odoj, K.; Garlasco, J.; Pezzani, M.D.; Magnabosco, C.; Ortiz, D.; Manco, F.; Galia, L.; Foster, S.K.; Arieti, F.; Tacconelli, E. Tracking Candidemia Trends and Antifungal Resistance Patterns across Europe: An In-Depth Analysis of Surveillance Systems and Surveillance Studies. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parslow, B.Y.; Thornton, C.R. Continuing Shifts in Epidemiology and Antifungal Susceptibility Highlight the Need for Improved Disease Management of Invasive Candidiasis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daneshnia, F.; de Almeida Júnior, J.N.; Ilkit, M.; Lombardi, L.; Perry, A.M.; Gao, M.; Nobile, C.J.; Egger, M.; Perlin, D.S.; Zhai, B.; et al. Worldwide emergence of fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis: Current framework and future research roadmap. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e470–e480, Erratum in: Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00188-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, R.; Srivastava, V. Application of anti-fungal vaccines as a tool against emerging anti-fungal resistance. Front. Fungal Biol. 2023, 4, 1241539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Patients enrolled | 364 | |

| Number of strains | 487 | |

| Period of study | 1st January 2015–31st December 2024 | |

| Annual distribution of cases | 2015 | 27 |

| 2016 | 15 | |

| 2017 | 28 | |

| 2018 | 32 | |

| 2019 | 33 | |

| 2020 | 29 | |

| 2021 | 49 | |

| 2022 | 84 | |

| 2023 | 68 | |

| 2024 | 72 | |

| Gender, Male | 265 (54.4%) | |

| Age (median (IQR)) | 71 (17) | |

| Hospitalization Ward | Frequency/Strains, % | Age Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Units | 290 (59.5%) | 76 (17) |

| Surgery Units | 91 (18.7%) | 69 (18) |

| DACC | 77 (15.8%) | 64 (24) |

| Intensive Care Units | 29 (6%) | 71 (10) |

| Candida spp. | Frequency/Strains, % | Frequency/Strains, % |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 282 (57.9%) | |

| C. non-albicans | 205 (42.1%) | |

| C. parapsilosis | 128 (26.3%) | |

| C. tropicalis | 35 (7.2%) | |

| N. glabratus | 28 (5.7%) | |

| M. guilliermondii | 12 (2.5%) | |

| Pichia kudriavzevii | 2 (0.4%) | |

| Total | 487 (100%) |

| C. albicans | C. non-albicans | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Units | Surgery | Count | 32 | 59 | 91 |

| % within a kind of unit | 35.2% | 64.8% | 100% | ||

| % within the kind of Candida spp. | 15.6% | 20.9% | 18.7% | ||

| Medical Units | Count | 135 | 155 | 290 | |

| % within kind of unit | 46.6% | 53.4% | 100% | ||

| % within the kind of Candida spp. | 65.9% | 55% | 59.5% | ||

| DACC | count | 24 | 53 | 77 | |

| % within a kind of unit | 31.2% | 68.8% | 100% | ||

| % within the kind of Candida spp. | 11.7% | 18.8% | 15.8% | ||

| Intensive Care Unit | count | 14 | 15 | 29 | |

| % within a kind of unit | 48.3% | 51.7% | 100% | ||

| % within the kind of Candida spp. | 6.8% | 5.3% | 6% | ||

| total | count | 205 | 282 | 487 | |

| % within a kind of unit | 42.1% | 57.9% | 100% | ||

| % within the kind of Candida spp. | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Value | Df | Asymptotic significance (2-sided) | |||

| Pearson chi-square | 8.382 | 3 | 0.039 (<0.05) | ||

| Likelihood ratio | 8.518 | 3 | 0.036 | ||

| N of valid cases | 487 | ||||

| Species (n) | Agent | Year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| C. albicans (n) | 19 | 9 | 14 | 13 | 17 | 19 | 38 | 62 | 51 | 51 | |

| Amph B | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 0 | |

| Caspofungin | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Fluconazole | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 6 | |

| Micafungin | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 3 | |

| Voriconazole | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 6 | |

| C. parapsilosis (n) | 13 | 8 | 7 | 14 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 10 | 26 | 39 | |

| Amph B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Caspofungin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Fluconazole | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| Micafungin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | |

| Voriconazole | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | |

| N. glabratus (n) | 6 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 7 | |

| Amph B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Caspofungin | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Fluconazole | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Micafungin | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Voriconazole | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| C. tropicalis (n) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 5 | |

| Amph B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Caspofungin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Fluconazole | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Micafungin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | I | 0 | 0 | |

| Voriconazole | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Spera, A.M.; Folliero, V.; D’Amore, C.; Santella, B.; Salzano, F.; Ascione, T.; Dell’Annunziata, F.; Serretiello, E.; Franci, G.; Pagliano, P. Nine-Year Surveillance of Candida Bloodstream Infections in a Southern Italian Tertiary Hospital: Species Distribution, Antifungal Resistance, and Stewardship Implications. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010017

Spera AM, Folliero V, D’Amore C, Santella B, Salzano F, Ascione T, Dell’Annunziata F, Serretiello E, Franci G, Pagliano P. Nine-Year Surveillance of Candida Bloodstream Infections in a Southern Italian Tertiary Hospital: Species Distribution, Antifungal Resistance, and Stewardship Implications. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpera, Anna Maria, Veronica Folliero, Chiara D’Amore, Biagio Santella, Flora Salzano, Tiziana Ascione, Federica Dell’Annunziata, Enrica Serretiello, Gianluigi Franci, and Pasquale Pagliano. 2026. "Nine-Year Surveillance of Candida Bloodstream Infections in a Southern Italian Tertiary Hospital: Species Distribution, Antifungal Resistance, and Stewardship Implications" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010017

APA StyleSpera, A. M., Folliero, V., D’Amore, C., Santella, B., Salzano, F., Ascione, T., Dell’Annunziata, F., Serretiello, E., Franci, G., & Pagliano, P. (2026). Nine-Year Surveillance of Candida Bloodstream Infections in a Southern Italian Tertiary Hospital: Species Distribution, Antifungal Resistance, and Stewardship Implications. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010017