An Altered Lipid Profile Is Indicative of Increased Insulin Requirement in Children and Adolescents at the Onset of Type 1 Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective of the Study

2.2. Study Cohort and Design

- Clinical parameters at diagnosis: Sex, age, body weight (kg), height (cm), body mass index (BMI), degree of weight loss at diagnosis (in % of reported weight), duration of diabetes symptoms before diagnosis, pubertal stage, presence of celiac disease or autoimmune thyroiditis, any other medical treatment. Pubertal status was assessed according to Tanner staging and included as a covariate in the analyses. Standard Deviations (SDs) for height, weight, and BMI were adjusted for age and gender according to Italian reference standards [12]. Celiac disease was diagnosed according to the ESPGHAN guidelines in force at the time of diagnosis, based on positive serological testing, with histological confirmation by duodenal biopsy when indicated [13,14].

- Laboratory parameters at diagnosis: Blood glucose (mg/dL), HbA1c (% and mmol/mol), fructosamine (μmol/L), presence of DKA (defined by venous pH < 7.3 and/or bicarbonate (HCO3−) < 15 mmol/L) [15], C-peptide (ng/mL), total cholesterol (mg/dL), HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL), triglycerides (mg/dL), uric acid (mg/dL), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH, microU/mL), and free thyroxine (fT4, pg/mL). Lipid profile was measured on the first blood sample collected at admission, before the initiation of intravenous insulin and, whenever feasible, before glucose infusion and extended rehydration. Although a formal fasting state could not be ensured, most patients—particularly those presenting with DKA—had markedly reduced oral intake for several hours before admission, resulting in a functional fasting condition. Therefore, triglyceride concentrations plausibly reflected a fasting-like metabolic condition and the acute metabolic stress at presentation, including lipolysis associated with DKA. Serum C-peptide levels were measured at diagnosis as a marker of residual β-cell function and were included among the covariates in both univariate and multivariable analyses assessing determinants of IR.

- Insulin therapy regimen during hospitalization: During hospitalization, insulin therapy was initiated and titrated according to the ISPAD 2022 guidelines for new-onset T1D. Glycemic targets were maintained between 100 and 180 mg/dL, with gradual adjustment of basal and bolus components under daily supervision by at least two pediatric endocrinologists, ensuring consistency and minimizing inter-observer variability. As defined above, IR was the highest total daily subcutaneous insulin dose (IU/kg/day) after DKA resolution and prior to discharge, reflecting the stable metabolic phase following rehydration. The highest subcutaneous insulin dose was chosen to capture the phase of maximal insulin resistance during acute metabolic instability, whereas discharge doses may underestimate early insulin needs due to subsequent titration aimed at hypoglycemia prevention. Subcutaneous TDD was recorded daily and expressed in IU/day and IU/kg, adjusted to the weight measured at admission. IV regimen was time-limited and restricted to patients with DKA at onset, according to ISPAD guidelines [1,6]. IR (IU/kg/day) was calculated by dividing TDD per body weight at diagnosis.

- Clinical parameters at discharge: Intravenous hydration duration (hours) and hospitalization duration (days).

- Clinical and laboratory parameters at 12 months’ follow-up: HbA1c (% and mmol/mol), total cholesterol (mg/dL), HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL), pubertal stage, and IR (IU/kg/day). The 12-month follow-up was selected as the secondary time-point because it generally represents the end of the partial remission (honeymoon) phase and the stabilization of insulin therapy, according to ISPAD 2022 guidelines [6]. A shorter (6-month) follow-up would still reflect honeymoon variability, while a longer (24-month) period would reduce the number of evaluable subjects and introduce heterogeneity due to pubertal changes.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Description

3.2. Subgroups Description

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glaser, N.; Fritsch, M.; Priyambada, L.; Rewers, A.; Cherubini, V.; Estrada, S.; Wolfsdorf, J.I.; Codner, E. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 835–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S17–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogle, G.D.; James, S.; Dabelea, D.; Pihoker, C.; Svennson, J.; Maniam, J.; Klatman, E.L.; Patterson, C.C. Global estimates of incidence of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Atlas, 10th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ILibman, I.; Haynes, A.; Lyons, S.; Pradeep, P.; Rwagasor, E.; Tung, J.Y.; Jefferies, C.A.; Oram, R.A.; Dabelea, D.; Craig, M.E. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Definition, epidemiology, and classification of diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1160–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornstad, P.; Dart, A.; Donaghue, K.C.; Dost, A.; Feldman, E.L.; Tan, G.S.; Wadwa, R.P.; Zabeen, B.; Marcovecchio, M.L. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Microvascular and macrovascular complications in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1432–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, E.; Danne, T.; Ahmad, T.; Ayyavoo, A.; Beran, D.; Ehtisham, S.; Fairchild, J.; Jarosz-Chobot, P.; Ng, S.M.; Paterson, M.; et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Insulin treatment in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1277–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadkowska, A.; Pietrzak, I.; Mianowska, B.; Bodalska-Lipińska, J.; Keenan, H.A.; Toporowska-Kowalska, E.; Młynarski, W.; Bodalski, J. Insulin sensitivity in Type 1 diabetic children and adolescents. Diabet. Med. 2008, 25, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, S.; Raile, K.; Reinehr, T.; Hofer, S.; Näke, A.; Rabl, W.; Holl, R.W. Daily insulin requirement of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Effect of age, gender, body mass index and mode of therapy. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2008, 158, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L. Diabetes Control in Thyroid Disease. Diabetes Spectr. 2006, 19, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bock, M.; Codner, E.; Craig, M.E.; Huynh, T.; Maahs, D.M.; Mahmud, F.H.; Marcovecchio, L.; DiMeglio, L.A. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Glycemic targets and glucose monitoring for children, adolescents, and young people with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Bannuru, R.R.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Ekhlaspour, L.; Hilliard, M.E.; Johnson, E.L.; Khunti, K.; et al. 6. Glycemic Goals and Hypoglycemia: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S111–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciari, E.; Milani, S.; Balsamo, A.; Spada, E.; Bona, G.; Cavallo, L.; Cerutti, F.; Gargantini, L.; Greggio, N.; Tonini, G.; et al. Italian cross-sectional growth charts for height, weight and BMI (2 to 20 yr). J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2006, 29, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; Mearin, M.L.; Phillips, A.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Giersiepen, K.; Branski, D.; Catassi, C.; et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 54, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.; Kurppa, K.; Mearin, M.L.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunger, D.B.; A Sperling, M.; Acerini, C.L.; Bohn, D.J.; Daneman, D.; A Danne, T.P.; Glaser, N.S.; Hanas, R.; Hintz, R.L.; Levitsky, L.L.; et al. ESPE/LWPES consensus statement on diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Arch. Dis. Child. 2004, 89, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, M.; Polle, O.; Gallo, P.; Bernard, N.; Bugli, C.; Lysy, P.A. Determinants and Characteristics of Insulin Dose Requirements in Children and Adolescents with New-Onset Type 1 Diabetes: Insights from the INSENODIAB Study. J. Diabetes Res. 2023, 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cemeroglu, A.P.; Thomas, J.P.; Zande, L.T.V.; Nguyen, N.T.; Wood, M.A.; Kleis, L.; Davis, A.T. Basal and Bolus Insulin Requirements in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults with type 1 Diabetes Mellitus on Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (csii): Effects of age and Puberty. Endocr. Pract. 2013, 19, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, U.; Westerberg, L.; Aakesson, K.; Birkebæk, N.H.; Bjarnason, R.; Drivvoll, A.K.; Skrivarhaug, T.; Svensson, J.; Thorsson, A.; Hanberger, L.; et al. Geographical variation in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in the Nordic countries: A study within NordicDiabKids. Pediatr. Diabetes 2019, 21, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holven, K.B.; van Lennep, J.R. Sex differences in lipids: A life course approach. Atherosclerosis 2023, 384, 117270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagi, V.M.; Samvelyan, S.; Chiarelli, F. An update of the consensus statement on insulin resistance in children 2010. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1061524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, S.T.; Neylon, O.M.; O’brien, T. Dyslipidaemia in Type 1 Diabetes: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzela, D.; Pfeffera, U.; Dost, A.; Herbstc, A.; Knerr, I.; Holl, R. Initial insulin therapy in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr. Diabetes 2009, 11, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, M.; Wheeler, B.J.; Blackwell, M.; Colas, M.; Reith, D.M.; Medlicott, N.J.; Al-Sallami, H.S. The influence of patient variables on insulin total daily dose in paediatric inpatients with new onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2018, 17, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All | IR ≤ 1 IU/kg/Day | IR > 1 IU/kg/Day | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 8.2 ± 4.1 | 8.8 ± 4.0 | 7.6 ± 4.1 | NS |

| Body weight (kg) | 29.8 ± 15.5 | 32.4 ± 16.1 | 24.5 ± 12.5 | 0.001 |

| Weight loss (%) | 11.3 ± 7.1 | 9.6 ± 6.0 | 13.8 ± 8.5 | 0.01 |

| BMI z-score | −0.71 ± 1.25 | −0.60 ± 1.29 | −0.90 ± 1.22 | NS |

| DKA (%) | 37.2% | 29.2% | 54.1% | 0.02 |

| Severe DKA (%) | 14.2% | 8.5% | 25.7% | 0.009 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 101.0 ± 24.5 | 97.1 ± 24.2 | 108.8 ± 21.8 | <0.001 |

| Admission blood glucose (mg/dL) | 451.5 ± 216.0 | 413.2 ± 156.7 | 529.4 ± 285.0 | <0.001 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 0.55 ± 0.40 | 0.63 ± 0.44 | 0.41 ± 0.25 | 0.001 |

| Fructosamine (μmol/L) | 565.1 ± 164.5 | 550.1 ± 161.8 | 590.7 ± 158.9 | 0.04 |

| IR (IU/kg/day) | 0.92 ± 0.39 | - | - | - |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 184.8 ± 61.0 | 179.1 ± 48.7 | 195.0 ± 81.5 | NS |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 50.3 ± 31.5 | 51.9 ± 29.6 | 46.9 ± 36.8 | 0.001 |

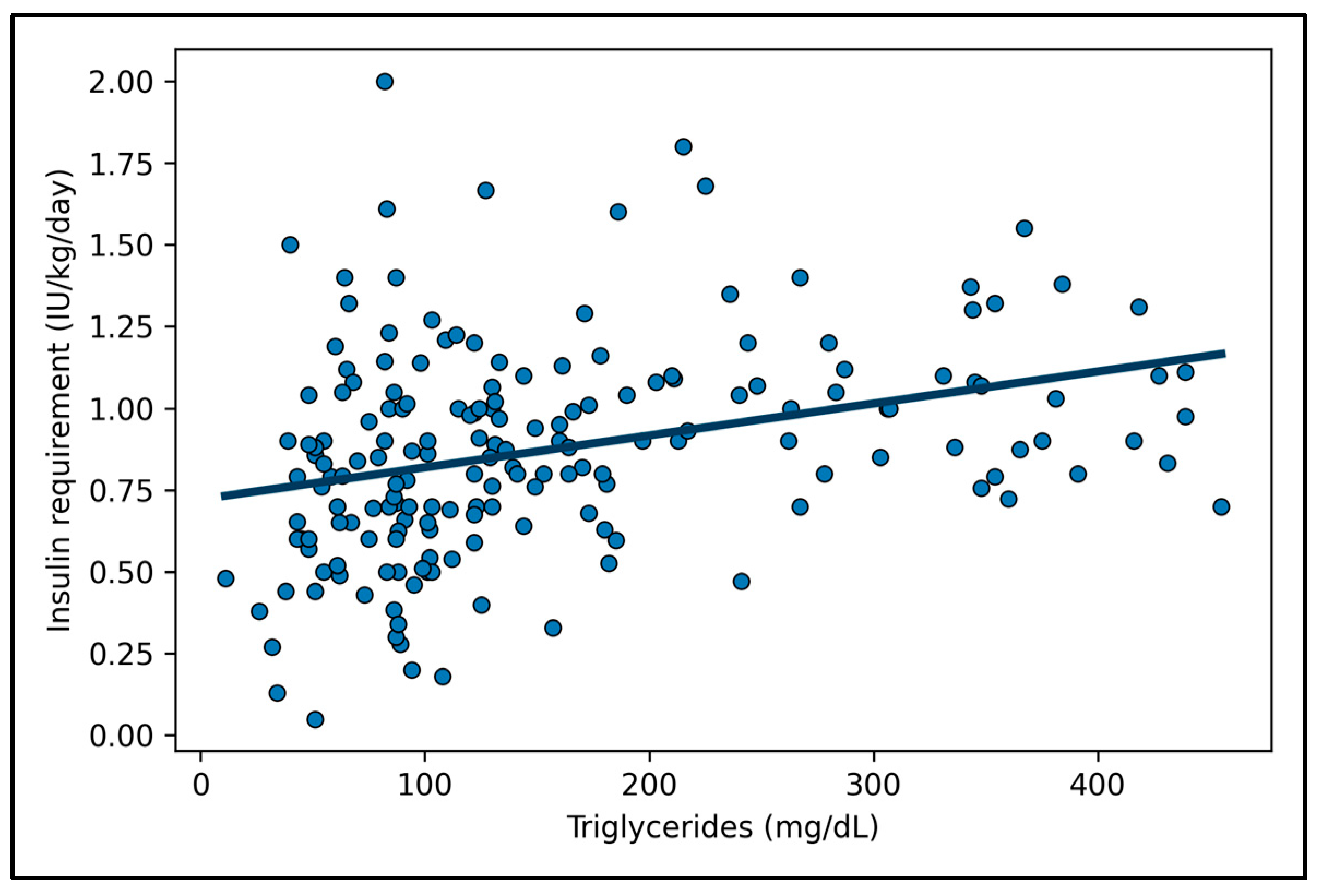

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 179.1 ± 156.1 | 153.1 ± 136.9 | 232.6 ± 179.5 | <0.001 |

| TSH (microU/mL) | 3.6 ± 4.3 | 4.1 ± 5.4 | 3.0 ± 1.7 | NS |

| fT4 (pg/mL) | 9.9 ± 1.8 | 10.0 ± 1.7 | 10.3 ± 9.7 | NS |

| Duration of symptoms (days) | 26.2 ± 23.9 | 24.7 ± 23.6 | 25.4 ± 23.5 | NS |

| Duration of hydration (hours) | 22.0 ± 32.4 | 17.3 ± 20.3 | 28.9 ± 42.9 | 0.002 |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | 9.4 ± 3.2 | 8.8 ± 2.8 | 10.4 ± 3.6 | 0.013 |

| pH | 7.26 ± 0.16 | 7.29 ± 0.16 | 7.20 ± 0.16 | <0.001 |

| HCO3− (mmol/L) | 17.3 ± 7.9 | 19.0 ± 7.2 | 14.2 ± 8.3 | <0.001 |

| Celiac disease | 12.8% | 13.3% | 13.3% | NS |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 14.7% | 14.8% | 16.0% | NS |

| FDR | 4.1% | 5.2% | 2.7% | NS |

| Prepubertal stage | 46.8% | 46.4% | 47.4% | NS |

| TG ≤ 150 mg/dL (T1D Onset) | TG > 150 mg/dL (T1D Onset) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 8.5 ± 3.7 | 8.1 ± 4.6 | NS |

| Body weight (kg) | 31.1 ± 14.9 | 28.9 ± 16.7 | NS |

| Weight loss (%) | 9.9 ± 5.9 | 12.6 ± 7.1 | NS |

| DKA (%) | 24.8% | 55.6% | 0.004 |

| Severe DKA (%) | 7.1% | 21.0% | 0.013 |

| Admission blood glucose (mg/dL) | 408.1 ± 163.8 | 513.7 ± 268.0 | <0.001 |

| Fructosamine (μmol/L) | 506.4 ± 142.7 | 649.9 ± 160.6 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 96.5 ± 22.8 | 108.0 ± 24.6 | 0.001 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 0.58 ± 0.42 | 0.51 ± 0.37 | NS |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 166.3 ± 42.3 | 210.9 ± 73.3 | <0.001 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 54.3 ± 28.4 | 44.9 ± 35.3 | <0.001 |

| IR (IU/kg/day) | 0.80 ± 0.34 | 1.06 ± 0.37 | <0.001 |

| TSH (microU/mL) | 2.80 ± 2.82 | 5.51 ± 6.30 | 0.011 |

| fT4 (pg/mL) | 10.40 ± 1.18 | 8.79 ± 2.46 | 0.038 |

| Duration of symptoms (days) | 25.5 ± 23.1 | 27.8 ± 23.6 | 0.025 |

| Duration of hydration (hours) | 18.6 ± 36.9 | 25.9 ± 25.0 | <0.001 |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | 8.9 ± 3.0 | 10.0 ± 3.2 | 0.006 |

| pH | 7.31 ± 0.13 | 7.21 ± 0.18 | <0.001 |

| HCO3− (mmol/L) | 19.4 ± 6.8 | 14.8 ± 8.3 | <0.001 |

| Variable | β (Unstandardized) | Standard Error | β (Unstandardized) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 0.000685 | 0.000190 | 0.271 | [0.000310; 0.001060] | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 0.002571 | 0.001126 | 0.166 | [0.000343; 0.004799] | 0.024 |

| pH | −0.280 | 0.198 | −0.107 | [−0.671; 0.112] | 0.160 |

| BMI z-score | −0.074 | 0.021 | −0.262 | [−0.116; −0.033] | <0.001 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | −0.206 | 0.069 | −0.224 | [−0.343; −0.070] | 0.003 |

| All Subjects | IR ≤ 1 IU/kg/Day (at T1D Onset) | IR > 1 IU/kg/Day (at T1D Onset) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 58.65 ± 14.9 | 58.5 ± 15.5 | 59.0 ± 14.4 | NS |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 172.6 ± 31.5 | 173.9 ± 33.7 | 170.8 ± 27.2 | NS |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 59.9 ± 13.7 | 61.3 ± 14.1 | 57.4 ± 12.9 | NS |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 67.2 ± 39.9 | 68.4 ± 65.5 | 65.1 ± 24.6 | NS |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 0.54 ± 0.63 | 0.63 ± 0.77 | 0.43 ± 0.38 | NS |

| IR (IU/kg/day) | 0.64 ± 0.31 | 0.60 ± 0.25 | 0.72 ± 0.38 | 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maltoni, G.; Bernardini, L.; Scozzarella, A.; Montanari, G.; Cantarelli, E.; Lanari, M. An Altered Lipid Profile Is Indicative of Increased Insulin Requirement in Children and Adolescents at the Onset of Type 1 Diabetes. J. Pers. Med. 2026, 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010014

Maltoni G, Bernardini L, Scozzarella A, Montanari G, Cantarelli E, Lanari M. An Altered Lipid Profile Is Indicative of Increased Insulin Requirement in Children and Adolescents at the Onset of Type 1 Diabetes. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2026; 16(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaltoni, Giulio, Luca Bernardini, Andrea Scozzarella, Giulia Montanari, Erika Cantarelli, and Marcello Lanari. 2026. "An Altered Lipid Profile Is Indicative of Increased Insulin Requirement in Children and Adolescents at the Onset of Type 1 Diabetes" Journal of Personalized Medicine 16, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010014

APA StyleMaltoni, G., Bernardini, L., Scozzarella, A., Montanari, G., Cantarelli, E., & Lanari, M. (2026). An Altered Lipid Profile Is Indicative of Increased Insulin Requirement in Children and Adolescents at the Onset of Type 1 Diabetes. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 16(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm16010014