Role of Polymer-Free Drug-Eluting Stents in Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: An Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

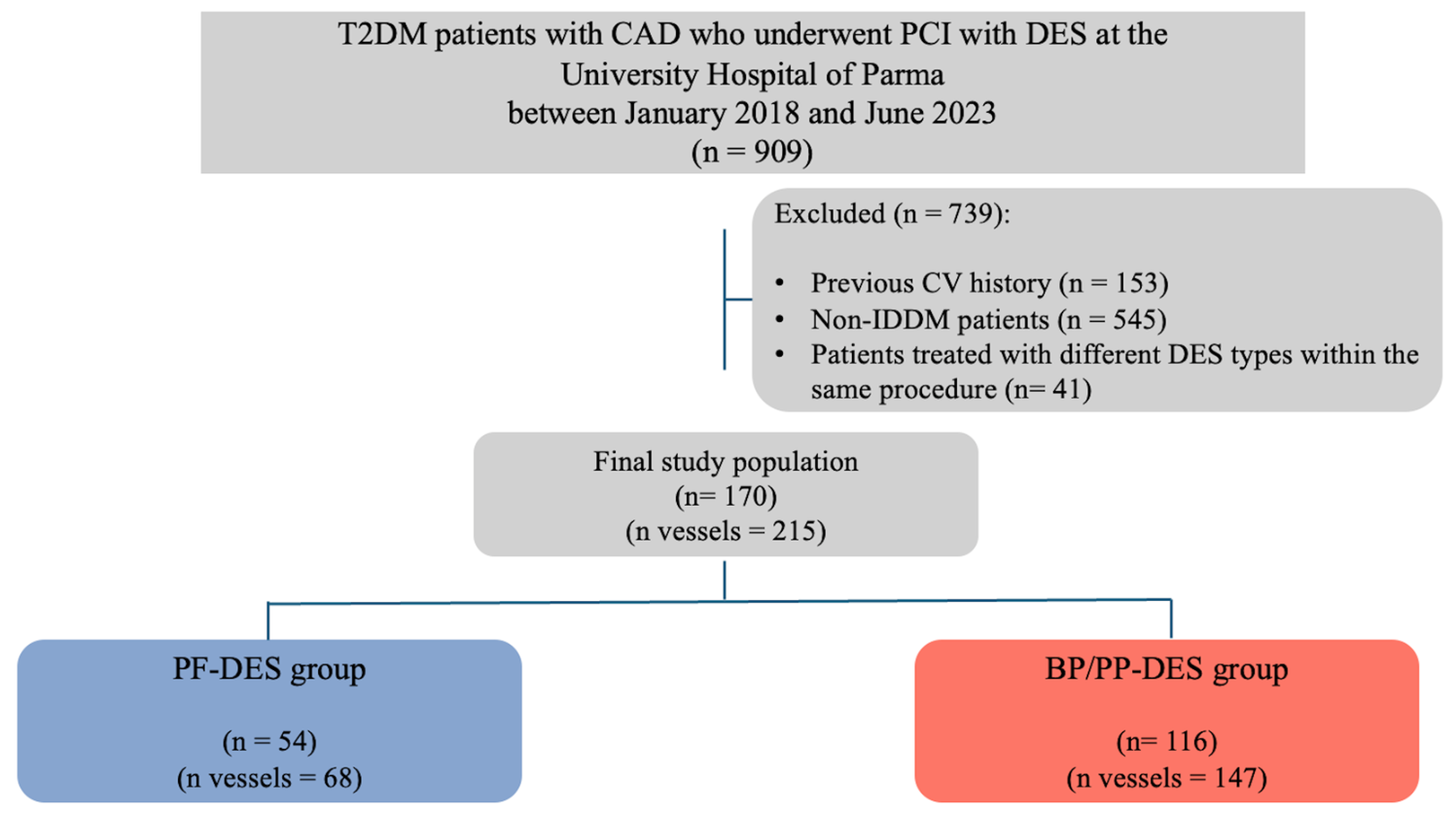

2. Materials and Methods

- Study Population

- Coronary angiography and PCI details

- Follow-up and clinical assessment

- Statistical analysis

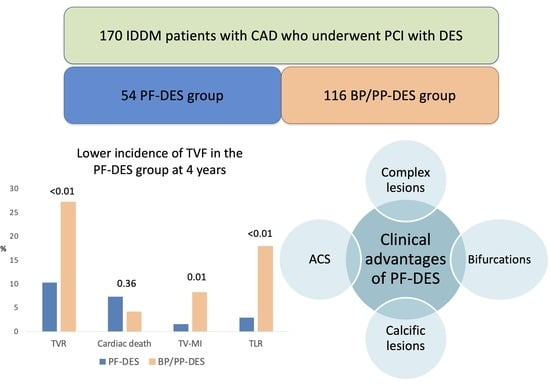

3. Results

- Clinical characteristics

- Angiographic and PCI data

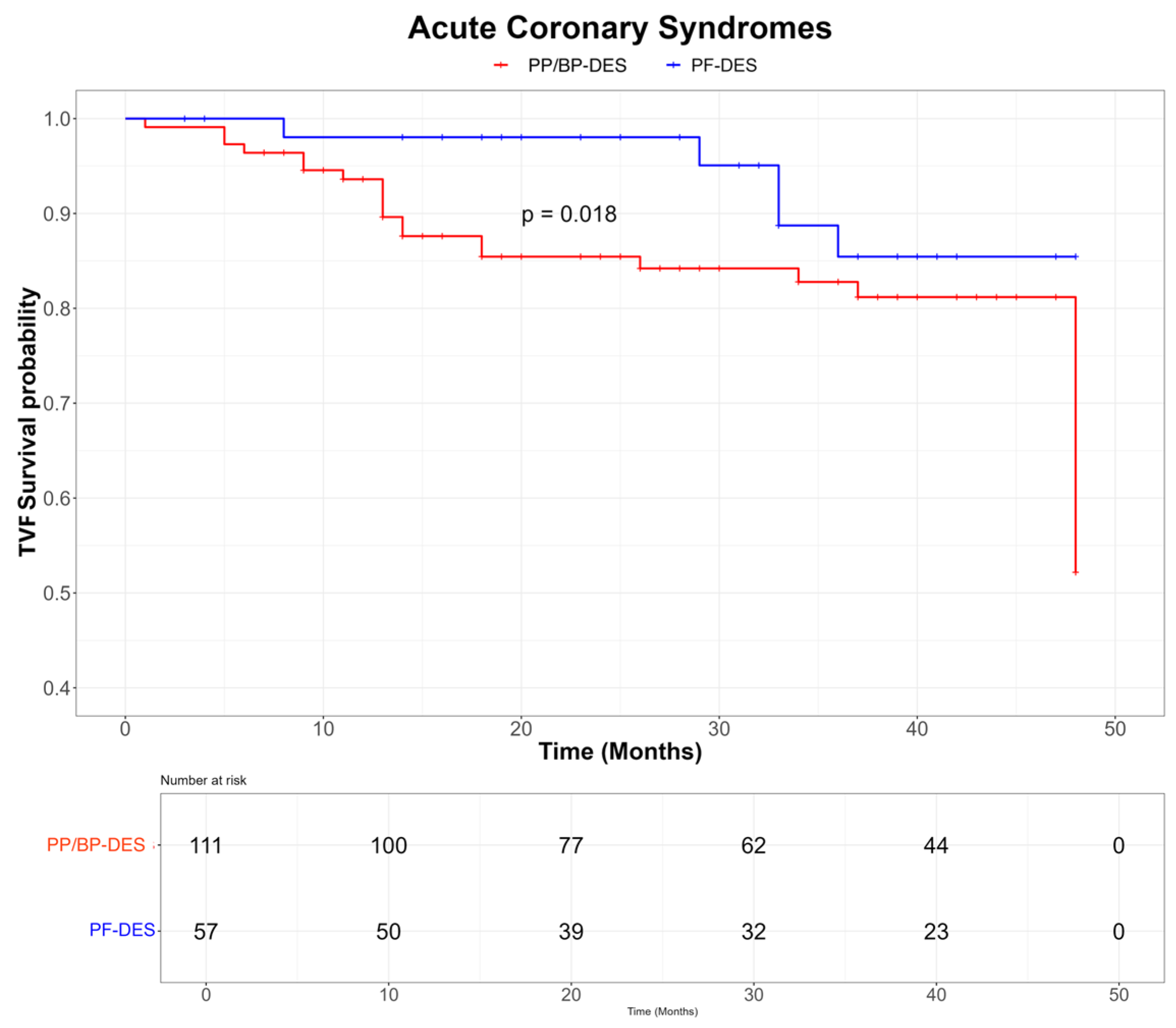

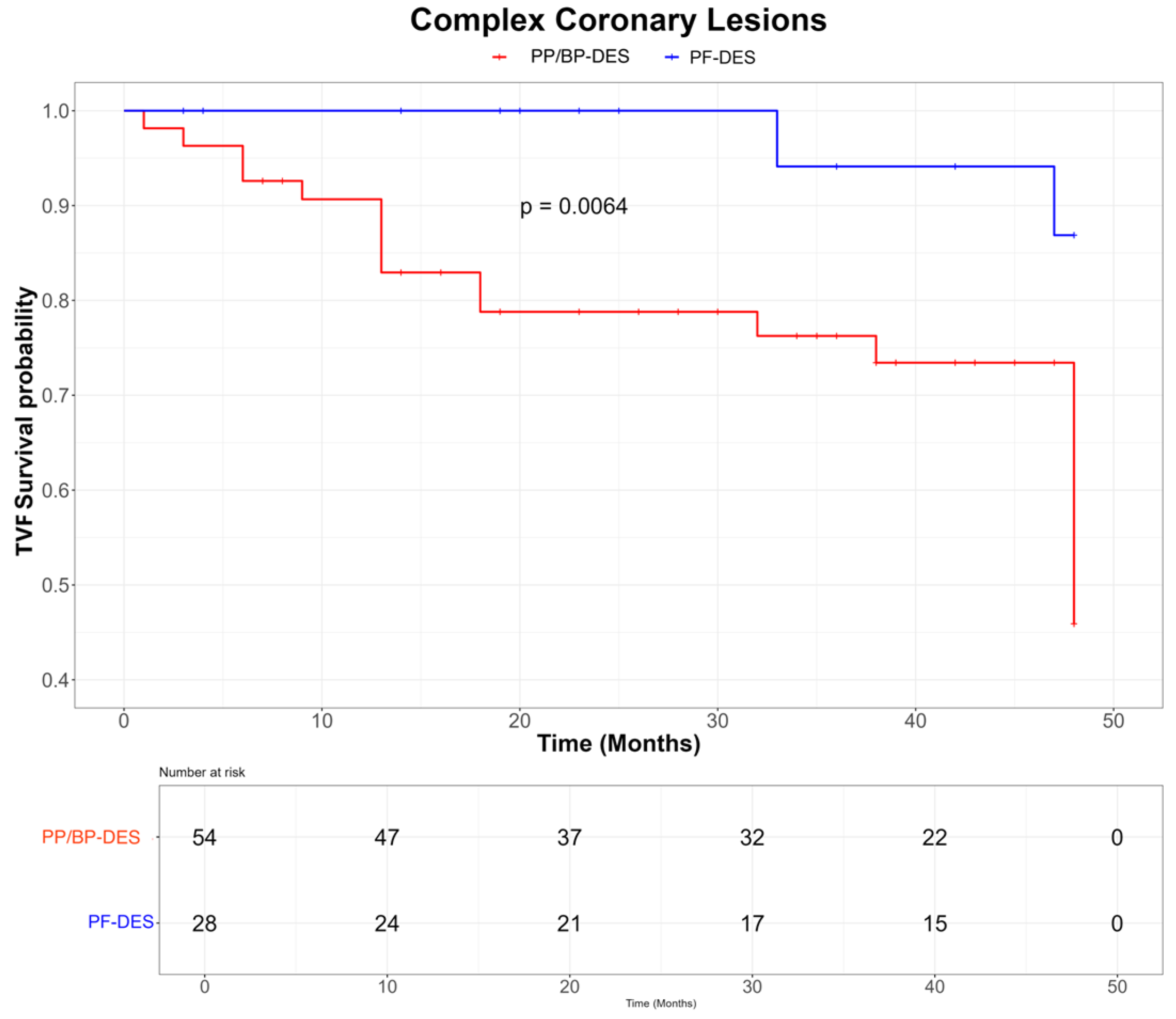

- Clinical outcomes

4. Discussion

- Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC/AHA | American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association |

| ACS | acute coronary syndrome |

| BP-DES | biodegradable-polymer drug-eluting stent |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| DCB | drug-coated balloon |

| DES | drug-eluting stent |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| HRs | hazard ratios |

| IDDM | insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus |

| KM | Kaplan–Meier |

| PCI | percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PF-DES | polymer-free drug-eluting stent |

| PP-DES | permanent-polymer drug eluting stent |

| PSM | propensity score matching |

| RCTs | randomized controlled trials |

| TLR | target lesion revascularization |

| TVF | target vessel failure |

| TVMI | target vessel myocardial infarction |

References

- Schramm, T.K.; Gislason, G.H.; Kober, L.; Rasmussen, S.; Rasmussen, J.N.; Abildstrom, S.Z.; Hansen, M.L.; Folke, F.; Buch, P.; Madsen, M.; et al. Diabetes patients requiring glucose-lowering therapy and nondiabetics with a prior myocardial infarction carry the same cardiovascular risk: A population study of 3.3 million people. Circulation 2008, 117, 1945–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, V.H.; Hobohm, L.; Münzel, T.; Wenzel, P.; Gori, T.; Keller, K. Impact of diabetes mellitus on mortality rates and outcomes in myocardial infarction. Diabetes Metab. 2021, 47, 101211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanini, G.G.; Byrne, R.A.; Windecker, S.; Kastrati, A. State of the art: Coronary artery stents—Past, present and future. EuroIntervention 2017, 13, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, T.; Polimeni, A.; Indolfi, C.; Räber, L.; Adriaenssens, T.; Münzel, T. Predictors of stent thrombosis and their implications for clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustino, G.; Colombo, A.; Camaj, A.; Yasumura, K.; Mehran, R.; Stone, G.W.; Kini, A.; Sharma, S.K. Coronary in-stent restenosis: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 348–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogic, J.; Andrianopoulos, N.; Farouque, O.; Lefkovits, J.; Brennan, A.; Reid, C.; Ajani, A.; Freeman, M.; Duffy, S.J.; Clark, D.; et al. Diabetes mellitus is independently associated with early stent thrombosis in patients undergoing drug-eluting stent implantation: Analysis from the Victorian Cardiac Outcomes Registry. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 99, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Mone, P.; Kansakar, U.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Donkor, K.; Adebayo, A.; Varzideh, F.; Eacobacci, M.; Gambardella, J.; Lombardi, A.; et al. Diabetes and restenosis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausleiter, J.; Kastrati, A.; Mehilli, J.; Schuhlen, H.; Pache, J.; Dotzer, F.; Dirschinger, J.; Schmitt, C.; Schomig, A. Prevention of restenosis by a novel drug-eluting stent system with a dose-adjustable, polymer-free, on-site stent coating. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, A.V.; Nakazawa, G.; Joner, M.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Mont, E.K.; Gold, H.K.; Virmani, R. Vascular responses to drug eluting stents: Importance of delayed healing. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 1500–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleran, R.; Byrne, R.A. Polymer-Free Drug-Eluting Stents: The Importance of the Right Control. Circulation 2020, 141, 2064–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsuaki, M.; Kozuma, K.; Morimoto, T.; Kadota, K.; Muramatsu, T.; Nakagawa, Y.; Akasaka, T.; Tanabe, K.; Morino, Y.; Kozuma, K.; et al. Biodegradable polymer biolimus-eluting stent versus durable polymer everolimus-eluting stent: A randomized, controlled, noninferiority trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Kastrati, A.; Kufner, S.; Massberg, S.; Birkmeier, K.A.; Laugwitz, K.L.; Schulz, S.; Pache, J.; Seyfarth, M.; Schömig, A.; et al. A polymer-free dual drug-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease: A randomized trial vs. polymer-based drug-eluting stents. Eur. Heart J. 2009, 30, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massberg, S.; Byrne, R.A.; Kastrati, A.; Schulz, S.; Pache, J.; Hausleiter, J.; Schömig, A.; Ott, I. Polymer-free sirolimus- and probucol-eluting versus new-generation zotarolimus-eluting stents in coronary artery disease: The ISAR-TEST 5 trial. Circulation 2011, 124, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krackhardt, F.; Kočka, V.; Waliszewski, M.W.; Utech, A.; Lustermann, M.; Hudec, M.; Studenčan, M.; Schwefer, M.; Yu, J.; Jeong, M.H.; et al. Polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stents in a large-scale all-comers population. Open Heart 2017, 4, e000592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdoia, M.; Kedhi, E.; Suryapranata, H.; Galasso, G.; Dudek, D.; De Luca, G. Polymer-free vs. polymer-coated drug-eluting stents for the treatment of coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis of 16 randomized trials. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2020, 21, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiermaier, T.; Heinz, A.; Schloma, D.; Kleinertz, K.; Dänschel, W.; Erbs, S.; Linke, A.; Boudriot, E.; Lauer, B.; Schuler, G.; et al. Five-year clinical follow-up of a randomized comparison of a polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stent versus a polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with diabetes mellitus (LIPSIA Yukon trial). Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 83, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hemert, N.D.; Voskuil, M.; Rozemeijer, R.; Stein, M.; Frambach, P.; Pereira, B.; Rittersma, S.Z.; Kraaijeveld, A.O.; Leenders, G.E.H.; Timmers, L.; et al. 3-year clinical outcomes after implantation of permanent-polymer versus polymer-free stent: ReCre8 Landmark Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 2477–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascencio-Lemus, M.G.; Romaguera, R.; Brugaletta, S.; Pinar, E.; Jimenez-Quevedo, P.; Gomez-Lara, J.; Ferreiro, J.L.; Comin-Colet, J.; Sabaté, M.; Gómez-Hospital, J.A. Amphilimus- versus everolimus-eluting stents in patients with diabetes mellitus: 5-year follow-up of the RESERVOIR trial. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2022, 43, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T.; Lenz, T.; Joner, M.; Xhepa, E.; Koppara, T.; Wiebe, J.; Coughlan, J.J.; Aytekin, A.; Ibrahim, T.; Kessler, T.; et al. Ten-year clinical outcomes of polymer-free versus durable polymer new-generation drug-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease with and without diabetes mellitus: Results of the ISAR-TEST 5 trial. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2021, 110, 1586–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.N.; Maeng, M.; Raungaard, B.; Engstrøm, T.; Veien, K.T.; Kristensen, S.D.; Ellert-Gregersen, J.; Jensen, S.E.; Junker, A.; Kahlert, J.; et al. Impact of diabetes on 1-year clinical outcome in patients undergoing revascularization with the BioFreedom stents or the Orsiro stents from the SORT OUT IX trial. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 99, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardt, G.; Maillard, L.; Nazzaro, M.S.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Carrié, D.; Iñiguez, A.; Garot, P.; Abdellaoui, M.; Morice, M.C.; Foley, D.; et al. Polymer-free drug-coated coronary stents in diabetic patients at high bleeding risk: A pre-specified sub-study of the LEADERS FREE trial. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2019, 108, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romaguera, R.; Salinas, P.; Gomez-Lara, J.; Brugaletta, S.; Gómez-Menchero, A.; Romero, M.A.; García-Blas, S.; Ocaranza, R.; Bordes, P.; Kockar, M.J.; et al. Amphilimus- vs. zotarolimus-eluting stents in patients with diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease: The SUGAR trial. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windecker, S.; Latib, A.; Kedhi, E.; Kirtane, A.J.; Kandzari, D.E.; Mehran, R.; Price, M.J.; Abizaid, A.; Simon, D.I.; Worthley, S.G.; et al. Polymer-based versus polymer-free stents in high bleeding risk patients: Final 2-year results from Onyx ONE. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgoglione, F.L.; Donelli, D.; Antonelli, M.; Vignali, L.; Benatti, G.; Solinas, E.; Tadonio, I.; Magnani, G.; Denegri, A.; Lazzeroni, D.; et al. Polymer-free stents for percutaneous coronary intervention in diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Future Cardiol. 2024, 20, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montone, R.A.; Pitocco, D.; Gurgoglione, F.L.; Rinaldi, R.; Del Buono, M.G.; Camilli, M.; Rizzi, A.; Tartaglione, L.; Rizzo, G.E.; Di Leo, M.; et al. Microvascular complications identify a specific coronary atherosclerotic phenotype in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundhun, P.K.; Li, N.; Chen, M.H. Adverse cardiovascular outcomes between insulin-treated and non-insulin-treated diabetic patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2015, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, J.; Dangas, G.; Baber, U.; Sartori, S.; Qadeer, A.; Aquino, M.; Vogel, B.; Faggioni, M.; Vijay, P.; Claessen, B.E.; et al. Impact of insulin-treated and non-insulin-treated diabetes compared to patients without diabetes on 1-year outcomes following contemporary PCI. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 96, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47 (Suppl. S1), S20–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianos, G.; Morel, M.A.; Kappetein, A.P.; Morice, M.C.; Colombo, A.; Dawkins, K.; van den Brand, M.; Van Dyck, N.; Russell, M.E.; Mohr, F.W.; et al. The SYNTAX score: An angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention 2005, 1, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, V.; van Klaveren, D.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Meliga, E.; Vergouwe, Y.; Chieffo, A.; Kappetein, A.P.; Colombo, A.; Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Mack, M.; et al. Anatomical and clinical characteristics to guide decision making between coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention for individual patients: Development and validation of SYNTAX score II. Lancet 2013, 381, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.G.; Vandormael, M.G.; Cowley, M.J.; DiSciascio, G.; Deligonul, U.; Topol, E.J.; Bulle, T.M. Coronary morphologic and clinical determinants of procedural outcome with angioplasty for multivessel coronary disease: Implications for patient selection. Circulation 1990, 82, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, F.J.; Sousa-Uva, M.; Ahlsson, A.; Alfonso, F.; Banning, A.P.; Benedetto, U.; Byrne, R.A.; Collet, J.P.; Falk, V.; Head, S.J.; et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 87–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; McFadden, E.P.; Farb, A.; Mehran, R.; Stone, G.W.; Spertus, J.; Onuma, Y.; Morel, M.A.; van Es, G.A.; Zuckerman, B.; et al. Standardized end point definitions for coronary intervention trials: The Academic Research Consortium-2 Consensus Document. Circulation 2018, 137, 2635–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarsini, R.; Tebaldi, M.; Rubino, F.; Sgreva, S.; Vescovo, G.; Barbierato, M.; Vicerè, A.; Galante, D.; Mammone, C.; Lunardi, M.; et al. Intracoronary physiology-guided percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with diabetes. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2023, 112, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hemert, N.D.; Rozemeijer, R.; Voskuil, M.; Stein, M.; Frambach, P.; Rittersma, S.Z.; Kraaijeveld, A.O.; Leenders, G.E.H.; van der Harst, P.; Agostoni, P.; et al. Clinical outcomes after permanent polymer or polymer-free stent implantation in patients with diabetes mellitus: The ReCre8 diabetes substudy. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 99, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Shao, J.; Lin, L.; Jiang, M.; Wang, L.; Lu, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, R. Immune and inflammation in acute coronary syndrome: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 4904217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcock, R.F.; Yong, A.S.; Ng, A.C.; Chow, V.; Cheruvu, C.; Aliprandi-Costa, B.; Lowe, H.C.; Kritharides, L.; Brieger, D.B. Acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary artery disease: Are they so different? Long-term outcomes in a contemporary PCI cohort. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastrati, A.; Schömig, A.; Elezi, S.; Dirschinger, J.; Mehilli, J.; Schühlen, H.; Blasini, R.; Neumann, F.J. Prognostic value of the modified American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stenosis morphology classification for long-term angiographic and clinical outcome after coronary stent placement. Circulation 1999, 100, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, H.; Dohi, T.; Miyauchi, K.; Takahashi, D.; Funamizu, T.; Shitara, J.; Wada, H.; Doi, S.; Kato, Y.; Okai, I.; et al. Clinical impact of complex percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc. Interv. Ther. 2020, 35, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdoia, M.; Nardin, M.; Rognoni, A.; Cortese, B. Drug-coated balloons in high-risk patients and diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of 10 studies. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 104, 1423–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöhrle, J.; Scheller, B.; Seeger, J.; Farah, A.; Ohlow, M.A.; Mangner, N.; Möbius-Winkler, S.; Weilenmann, D.; Stachel, G.; Leibundgut, G.; et al. Impact of diabetes on outcome with drug-coated balloons versus drug-eluting stents: The BASKET-SMALL 2 trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 1789–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niezgoda, P.; Kasprzak, M.; Kubica, J.; Kuźma, Ł.; Januszek, R.; Iwańczyk, S.; Tomasiewicz, B.; Bil, J.; Kowalewski, M.; Jaguszewski, M.; et al. Drug-eluting balloons and drug-eluting stents in diabetic patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention due to restenosis: DM-Dragon Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazzo, G.; Oliva, A.; Testa, L.; Heang, T.M.; Lee, C.Y.; Milazzo, D.; Stefanini, G.; Pesenti, N.; Mangieri, A.; Colombo, A.; et al. Sirolimus-coated balloon in an all-comer population of coronary artery disease patients: The EASTBOURNE DIABETES prospective registry. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurgoglione, F.L.; Iwańczyk, S.; Wańha, W.; Donelli, D.; Gattuso, D.; Niccoli, G.; Cortese, B. Sirolimus-coated balloon versus drug-eluting stent in elderly patients with coronary artery disease: A matched-based comparison. Am. J. Cardiol. 2025, 255, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurgoglione, F.L.; Gattuso, D.; Greco, A.; Benatti, G.; Niccoli, G.; Cortese, B. Predictors and long-term prognostic significance of bailout stenting during percutaneous coronary interventions with sirolimus-coated balloon: A subanalysis of the Eastbourne study. Am. J. Cardiol. 2025, 239, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgoglione, F.L.; Gattuso, D.; Greco, A.; Donelli, D.; Niccoli, G.; Cortese, B. Angiographic and clinical impact of balloon inflation time in percutaneous coronary interventions with sirolimus-coated balloon: A subanalysis of the EASTBOURNE study. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2025, 73, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Overall Population (n = 170) | PF-DES Group (n = 54) | BP/PP-DES Group (n = 116) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age [years, mean (SD)] | 69.4 (11.6) | 69.9 (12.2) | 69.1 (11.3) | 0.48 |

| Male sex [n, (%)] | 79 (46.5) | 24 (44.4) | 55 (47.4) | 0.59 |

| Hypertension [n, (%)] | 147 (86.5) | 48 (88.9) | 99 (85.3) | 0.48 |

| Smoking habit [n, (%)] | 88 (51.8) | 31 (57.4) | 57 (49.1) | 0.44 |

| Dyslipidaemia [n, (%)] | 134 (78.8) | 39 (72.2) | 95 (81.9) | 0.15 |

| BMI [mean (SD)] | 28.1 (4.7) | 28.1 (4.7) | 28.1 (4.7) | 0.66 |

| Family history of CAD [n, (%)] | 139 (81.8) | 11 (20.4) | 20 (17.2) | 0.54 |

| CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) [n, (%)] | 46 (27.1) | 19 (35.2) | 27 (23.3) | 0.10 |

| AF [n, (%)] | 16 (9.4) | 6 (11.1) | 10 (8.6) | 0.57 |

| History of stroke [n, (%)] | 6 (3.5) | 1 (1.9) | 5 (4.3) | 0.50 |

| Clinical presentation [n, (%)] | 0.32 | |||

| CCS | 40 (23.5) | 9 (16.7) | 31 (26.7) | |

| Unstable angina | 7 (4.1) | 2 (3.7) | 5 (4.3) | |

| NSTEMI | 87 (51.2) | 29 (53.7) | 58 (50.0) | |

| STEMI | 36 (21.2) | 14 (25.9) | 22 (19.0) | |

| Laboratory data [median (IQR)] | ||||

| Hb (g/dL) [mean (SD)] | 13.0 (1.8) | 13.1 (1.8) | 12.9 (1.8) | 0.39 |

| PLT (U/μL) [mean (SD)] | 235.782 (71.015) | 235.592 (69.905) | 235.870 (71.827) | 0.68 |

| WBC (U/μL) [mean (SD)] | 9.029 (3.759) | 8.772 (2.711) | 9.148 (4.163) | 0.38 |

| Glycaemia (mg/dL) [mean (SD)] | 159.18 (72.62) | 165.30 (67.06) | 156.33 (75.17) | 0.32 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) [mean (SD)] | 64.32 (19.76) | 64.78 (19.46) | 64.10 (19.98) | 0.58 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) [mean (SD)] | 166.91 (52.27) | 166.80 (53.58) | 166.96 (51.88) | 0.68 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) [mean (SD)] | 93.54 (41.46) | 94.19 (41.92) | 93.24 (41.42) | 0.62 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) [mean (SD)] | 43.58 (11.27) | 42.39 (11.26) | 44.14 (11.28) | 0.24 |

| Serum creatinine on admission (mg/dL) [mean (SD)] | 1.28 (1.29) | 1.41 (1.29) | 1.23 (1.28) | 0.27 |

| Echocardiographic data | ||||

| LVEF on admission (%) [mean (SD)] | 47.26 (10.80) | 48.09 (10.45) | 46.88 (10.98) | 0.35 |

| Angiographic data | ||||

| SYNTAX Score (mean (SD)) | 13.05 (6.08) | 13.22 (6.29) | 12.97 (6.00) | 0.55 |

| SYNTAX 2 Score (mean (SD)) | 38.17 (12.24) | 38.69 (11.69) | 37.92 (12.53) | 0.49 |

| Number of Diseased Vessels (n (%)) | 0.53 | |||

| 1 | 129 (75.9) | 42 (77.8) | 87 (75.0) | |

| 2 | 40 (23.5) | 12 (22.2) | 28 (24.1) | |

| 3 | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Left Main (n (%)) | 6 (3.5) | 2 (3.7) | 4 (3.4) | 0.06 |

| Left Anterior Descending Artery (n (%)) | 108 (63.5) | 39 (72.2) | 69 (59.5) | 0.10 |

| Left Circumflex Artery (n (%)) | 42 (24.7) | 14 (25.9) | 28 (24.1) | 0.66 |

| Right Coronary Artery (n (%)) | 55 (32.4) | 12 (22.2) | 43 (37.1) | 0.06 |

| Number of Lesions Treated (n (%)) | 0.55 | |||

| 1 | 126 (74.1) | 40 (74.1) | 86 (74.1) | |

| 2 | 43 (25.3) | 14 (25.9) | 29 (25.0) | |

| 3 | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Therapy at discharge [n, (%)] | ||||

| Cardioaspirin | 165 (97.1) | 53 (98.1) | 112 (96.6) | 0.53 |

| Clopidogrel | 93 (54.7) | 29 (53.7) | 64 (55.2) | 0.86 |

| Ticagrelor | 52 (30.6) | 15 (27.8) | 37 (31.9) | 0.59 |

| Prasugrel | 23 (13.5) | 9 (16.7) | 14 (12.1) | 0.44 |

| OAC | 16 (9.4) | 4 (7.4) | 12 (10.3) | 0.52 |

| β-blockers | 160 (94.1) | 53 (98.1) | 107 (92.2) | 0.06 |

| CCBs | 65 (38.2) | 20 (37.0) | 45 (38.8) | 0.83 |

| ACE-i/ARBs | 120 (70.6) | 36 (66.7) | 84 (72.4) | 0.46 |

| Statin | 154 (90.6) | 48 (88.9) | 106 (91.4) | 0.62 |

| Ezetimibe | 25 (14.7) | 7 (13.0) | 18 (15.5) | 0.64 |

| Diuretics | 71 (41.8) | 23 (42.6) | 48 (41.4) | 0.88 |

| Median DAPT duration (months) (median [IQR]) | 12 [6; 12] | 12 [9; 12] | 12 [6; 12] | 0.96 |

| Median TAT duration (months) (median [IQR]) | 1 [1; 3] | 1 [1; 3] | 1 [1; 3] | 0.98 |

| Characteristics | Overall Population (n = 215) | PF-DES Group (n = 68) | BP/PP-DES Group (n = 147) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiographic and PCI data ACC/AHA classification [n, (%)] | 0.48 | |||

| A | 27 (12.6) | 11 (16.2) | 16 (47.4) | |

| B1 | 106 (49.3) | 29 (42.6) | 77 (10.9) | |

| B2 | 67 (31.2) | 22 (32.3) | 45 (30.6) | |

| C | 15 (7.0) | 6 (8.8) | 9 (6.1) | |

| ACC-AHA complex lesions [n, (%)] | 82 (38.1) | 28 (41.2) | 54 (36.7) | 0.53 |

| Calcific lesions [n, (%)] | 80 (37.2) | 28 (41.2) | 52 (35.4) | 0.42 |

| Bifurcations [n, (%)] | 66 (30.7) | 24 (35.3) | 42 (28.6) | 0.33 |

| Number of stents per patient [mean (SD)] | 1.62 (0.69) | 1.51 (0.61) | 1.67 (0.71) | 0.08 |

| Total stent length [mean (SD)] | 38.10 (17.24) | 37.16 (16.57) | 38.54 (17.58) | 0.41 |

| Implanted DES [n, (%)] | 0.32 | |||

| BiofreedomTM | 5 (2.3) | 5 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CoroflexTM | 50 (23.3) | 50 (73.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cre8TM | 13 (6.0) | 13 (19.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CruzTM | 24 (11.2) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (16.3) | |

| SynergyTM | 18 (8.4) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (12.2) | |

| OnyxTM | 4 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.7) | |

| PromusTM | 13 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (8.8) | |

| XienceTM | 88 (40.9) | 0 (0.0) | 88 (59.9) | |

| Outcomes data | ||||

| TVF [n, (%)] | 47 (21.9) | 7 (10.3) | 40 (27.2) | <0.01 |

| Cardiac death [n, (%)] | 11 (5.1) | 5 (7.3) | 6 (4.1) | 0.36 |

| TVMI [n, (%)] | 13 (6.0) | 1 (1.5) | 12 (8.2) | 0.01 |

| TLR [n, (%)] | 28 (13.0) | 2 (2.9) | 26 (17.9) | <0.01 |

| ST [n, (%)] | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | 0.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gurgoglione, F.L.; Donelli, D.; Frazzetto, M.; Vignali, L.; Benatti, G.; Tadonio, I.; Denegri, A.; Covani, M.; De Gregorio, M.; Dallaglio, G.; et al. Role of Polymer-Free Drug-Eluting Stents in Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: An Observational Study. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120594

Gurgoglione FL, Donelli D, Frazzetto M, Vignali L, Benatti G, Tadonio I, Denegri A, Covani M, De Gregorio M, Dallaglio G, et al. Role of Polymer-Free Drug-Eluting Stents in Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: An Observational Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):594. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120594

Chicago/Turabian StyleGurgoglione, Filippo Luca, Davide Donelli, Marco Frazzetto, Luigi Vignali, Giorgio Benatti, Iacopo Tadonio, Andrea Denegri, Marco Covani, Mattia De Gregorio, Gabriella Dallaglio, and et al. 2025. "Role of Polymer-Free Drug-Eluting Stents in Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: An Observational Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120594

APA StyleGurgoglione, F. L., Donelli, D., Frazzetto, M., Vignali, L., Benatti, G., Tadonio, I., Denegri, A., Covani, M., De Gregorio, M., Dallaglio, G., Niccoli, G., Cortese, B., & Solinas, E. (2025). Role of Polymer-Free Drug-Eluting Stents in Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: An Observational Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120594