When Blood Remembers Its Sex: Toward Truly Personalized Transfusion Medicine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Role of Gender in Donor Motivation and Behavioral Dynamics

3. The Role of Donor Sex in Blood Donor Eligibility Criteria

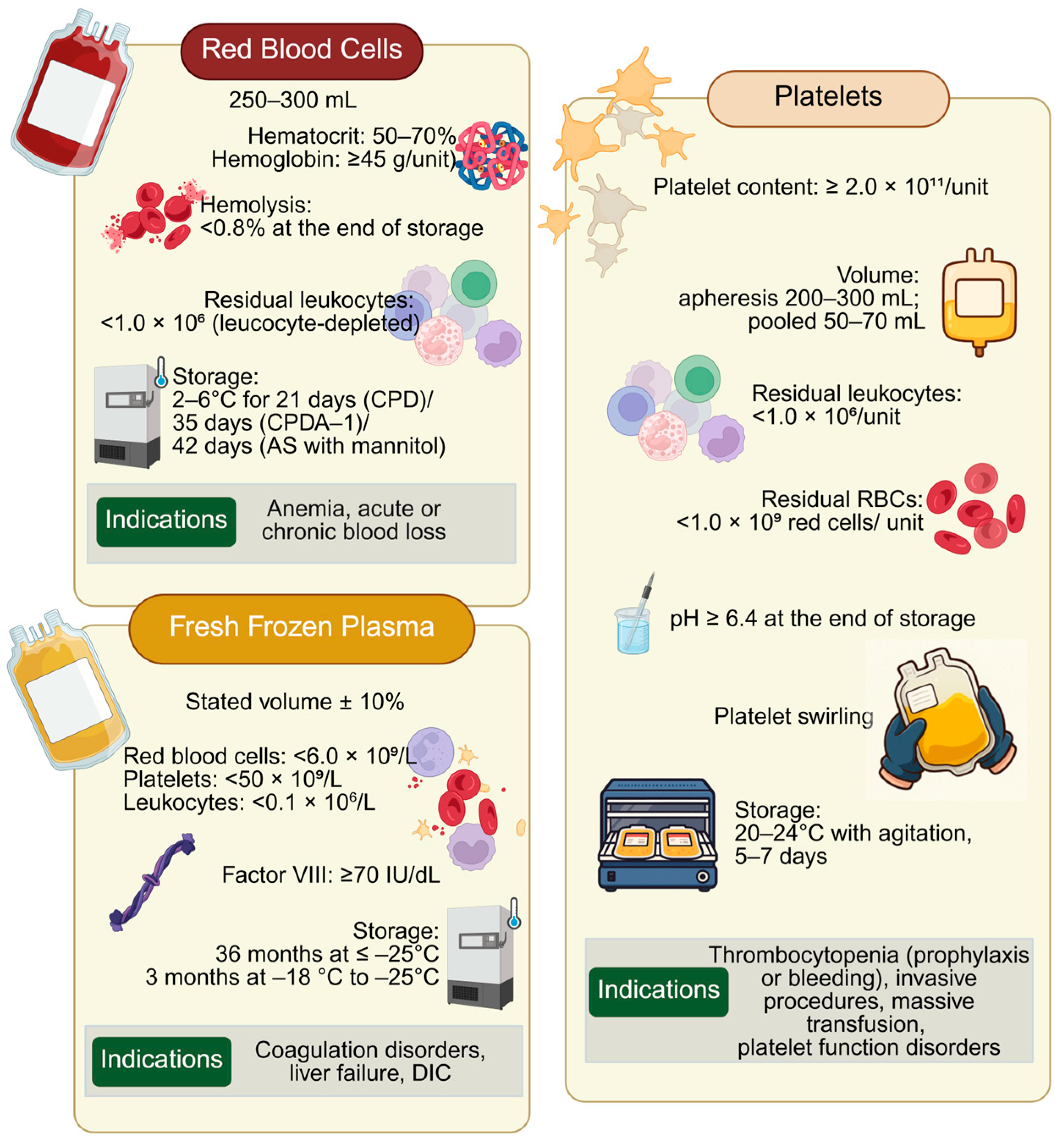

4. Sex-Related Differences in Blood Products: Focus on RBCs, Platelets and Plasma

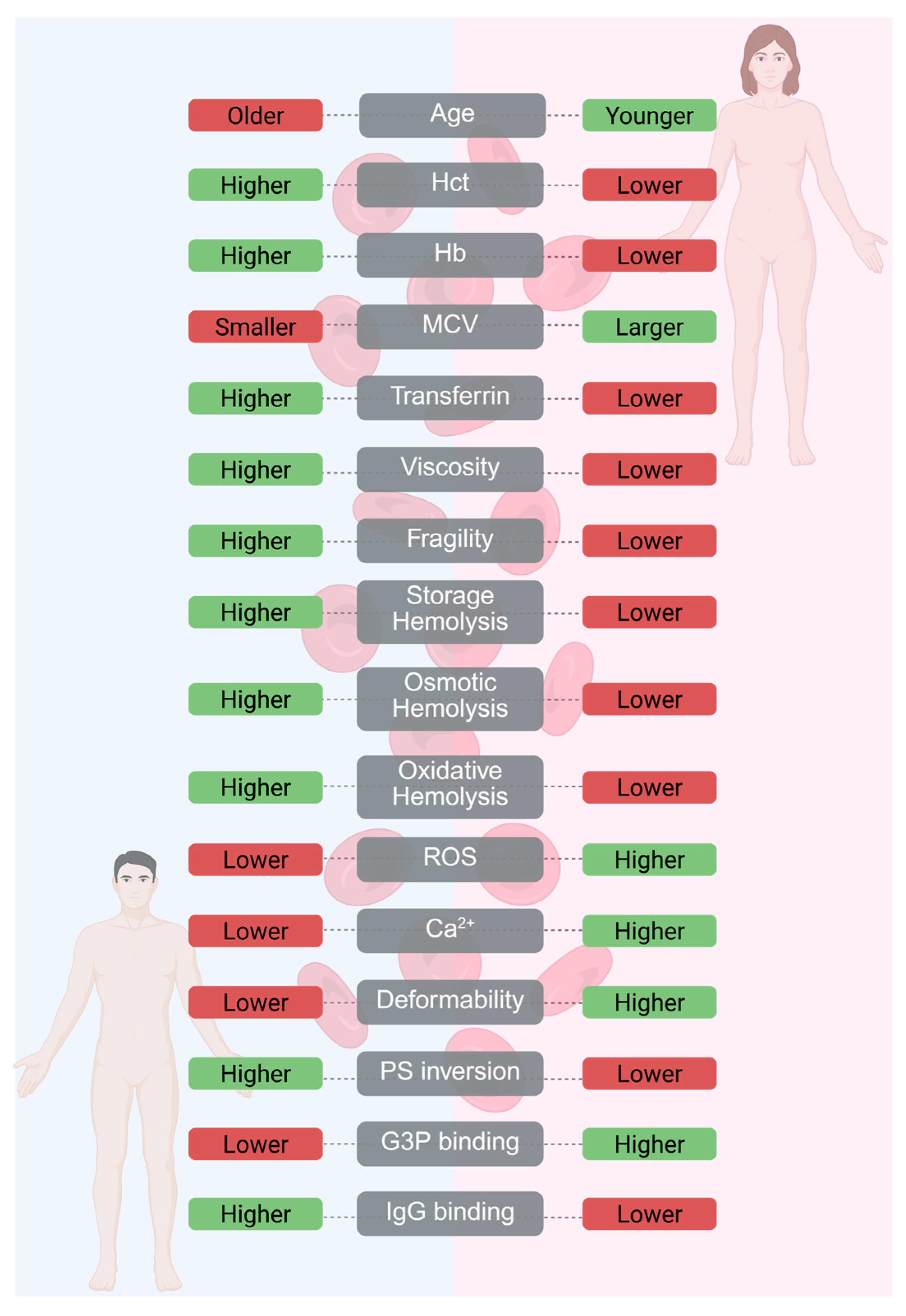

4.1. RBCs Blood Products for Transfusion—Sex-Related Differences

4.2. Plasma Products for Transfusion, Sex-Related Differences

4.3. Platelet Products for Transfusion, Sex-Related Differences

5. Impact of Donor–Recipient Sex Matching on Transfusion Outcomes

Donor–Recipient Sex Matching in RBC Transfusions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AABB | Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies |

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| CBC | Complete Blood Count |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CPD | Citrate–Phosphate–Dextrose |

| CPDA-1 | Citrate–Phosphate–Dextrose–Adenine |

| DIC | Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation |

| FFP | Fresh Frozen Plasma |

| F→M | Female donor to Male recipient (transfusion) |

| GLRX | Glutaredoxin-1 |

| GPX4 | Glutathione Peroxidase 4 |

| G3P | Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate |

| G6PD | Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase |

| Hct | Hematocrit |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| HNA | Human Neutrophil Antigen |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| MCV | Mean Corpuscular Volume |

| MCHC | Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration |

| M→F | Male donor to Female recipient (transfusion) |

| NHSBT | National Health Service Blood and Transplant (UK) |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PAS | Platelet Additive Solution |

| PLTs | Platelets |

| PRP | Platelet-Rich Plasma |

| PTP | Post-Transfusion Purpura |

| QC | Quality Control |

| RBCs | Red Blood Cells |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| sTM | Soluble Thrombomodulin |

| SHOT | Serious Hazards of Transfusion (UK haemovigilance) |

| TRALI | Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury |

| TRIM | Transfusion-Related Immunomodulation |

| vWD | von Willebrand Disease |

| WB | Whole Blood |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Hood, L.; Friend, S.H. Predictive, personalized, preventive, participatory (P4) cancer medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-M.; Hsiao, T.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Fann, Y.C. Unlocking precision medicine: Clinical applications of integrating health records, genetics, and immunology through artificial intelligence. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jameson, J.L.; Longo, D.L. Precision medicine—personalized, problematic, and promising. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, R.F.; Gebhard, C.E.; Gebhard, C. Integrating gender medicine into modern healthcare: Progress and barriers. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 55, e70089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Bairey Merz, N.; Barnes, P.J.; Brinton, R.D.; Carrero, J.J.; DeMeo, D.L.; De Vries, G.J.; Epperson, C.N.; Govindan, R.; Klein, S.L.; et al. Sex and gender: Modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet 2020, 396, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, I.; Prendergast, B.J. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics predict adverse drug reactions in women. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubinian, N.H.; Reese, S.E.; Qiao, H.; Plimier, C.; Fang, F.; Page, G.P.; Cable, R.G.; Custer, B.; Gladwin, M.T.; Goel, R.; et al. Donor genetic and nongenetic factors affecting red blood cell transfusion effectiveness. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e152598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, L.A.; Spitalnik, S.L. Transfusion-related immunomodulation: A reappraisal. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2017, 24, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, K. Blood Donation. JAMA 2023, 330, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.A.; Arnold, P.; Bingham, R.M.; Brohi, K.; Clark, R.; Collis, R.; Gill, R.; McSporran, W.; Moor, P.; Rao Baikady, R.; et al. AAGBI guidelines: The use of blood components and their alternatives 2016. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Voluntary unpaid blood donations must increase rapidly to meet 2020 goal. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 819–820. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. In Towards 100% Voluntary Blood Donation: A Global Framework for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, L.S.; Stanley, J.; Bloch, E.M.; Pagano, M.B.; Ipe, T.S.; Eichbaum, Q.; Wendel, S.; Indrikovs, A.; Cai, W.; Delaney, M. Status of hospital-based blood transfusion services in low-income and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional international survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.; James, S.; Delaney, M.; Fitzmaurice, C. The global need and availability of blood products: A modelling study. Lancet. Haematol. 2019, 6, e606–e615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raykar, N.P.; Makin, J.; Khajanchi, M.; Olayo, B.; Valencia, A.M.; Roy, N.; Ottolino, P.; Zinco, A.; MacLeod, J.; Yazer, M.; et al. Assessing the global burden of hemorrhage: The global blood supply, deficits, and potential solutions. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211054995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, M.R.; Eschliman, E.L.; Karver, T.S. Differentiating sex and gender in health research to achieve gender equity. Bull. World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Fu, X.; Kanias, T.; Reisz, J.A.; Culp-Hill, R.; Guo, Y.; Gladwin, M.T.; Page, G.; Kleinman, S.; Lanteri, M.; et al. Donor sex, age and ethnicity impact stored red blood cell antioxidant metabolism through mechanisms in part explained by glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase levels and activity. Haematologica 2021, 106, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassé, M.; Fergusson, D.A.; Tinmouth, A.; Acker, J.P.; Perelman, I.; Tuttle, A.; English, S.W.; Hawken, S.; Forster, A.J.; Shehata, N.; et al. Effect of Donor Sex on Recipient Mortality in Transfusion. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1386–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanias, T.; Lanteri, M.C.; Page, G.P.; Guo, Y.; Endres, S.M.; Stone, M.; Keating, S.; Mast, A.E.; Cable, R.G.; Triulzi, D.J.; et al. Ethnicity, sex, and age are determinants of red blood cell storage and stress hemolysis: Results of the REDS-III RBC-Omics study. Blood Adv. 2017, 1, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaux, O.; Bouazzi, L.; Sanchez, A.; Hottois, J.; Martin, M.-C.; Chrusciel, J.; Sanchez, S. Impact of Promoting Blood Donation in General Practice: Prospective Study among Blood Donors in France. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 1080096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Blood Safety and Availability 2021, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bednall, T.C.; Bove, L.L. Donating blood: A meta-analytic review of self-reported motivators and deterrents. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2011, 25, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, A.; Chell, K.; Davison, T.E.; Masser, B.M. What motivates men to donate blood? A systematic review of the evidence. Vox Sang. 2018, 113, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, S.D.; France, C.L.; West-Mitchell, K.A.; Pina, T.; McElfresh, D.; Sayers, M.; Bryant, B.J. Advancing Understandings of Blood Donation Motivation and Behavior. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2023, 37, 150780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldhuizen, I.; Ferguson, E.; de Kort, W.; Donders, R.; Atsma, F. Exploring the dynamics of the theory of planned behavior in the context of blood donation: Does donation experience make a difference? Transfusion 2011, 51, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lownik, E.; Riley, E.; Konstenius, T.; Riley, W.; McCullough, J. Knowledge, attitudes and practices surveys of blood donation in developing countries. Vox Sang. 2012, 103, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaller, N.; Nelson, K.E.; Ness, P.; Wen, G.; Bai, X.; Shan, H. Knowledge, attitude and practice survey regarding blood donation in a Northwestern Chinese city. Transfus. Med. 2005, 15, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Masalmeh Bel, D. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding blood donation among the Saudi population. Saudi Med. J. 2004, 25, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, F.; Tavabi, A.A.; Golestan, B.; Ammar-Saeedi, E.; Kashani, H.; Tabatabaei, R.; Iran-Pour, E. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards blood donation in Iranian population. Transfus. Med. 2011, 21, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, S.A.; Kleinman, S.H.; Schreiber, G.B.; Zuck, T.; Combs, S.M.; Bethel, J.; Garratty, G.; Williams, A.E. Motivations to donate blood: Demographic comparisons. Transfusion 2002, 42, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, R. Women blood donation drive in 21st century: A theme ‘so near yet so far’ for world blood donors day. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2025, 32, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani, M.; Giussani, B. Gender differences in giving blood: A review of the literature. Blood Transfus. 2010, 8, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segbefia, C.; Telke, S.; Olayemi, E.; Ward, C.; Asamoah-Akuoko, L.; Appiah, B.; Yawson, A.E.; Tancred, T.; Adu-Afarwuah, S.; Kuma, A.B.-A.; et al. Deferrals for Low Haemoglobin and Anaemia Among First-Time Prospective Blood Donors in Southern Ghana: Results from the BLOODSAFE Ghana—Iron and Nutritional Counselling Strategy Pilot (BLIS) Study. Adv. Hematol. 2025, 2025, 9971532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortis, S.P.; Kriebardis, A.G.; Georgatzakou, H.T.; Lyrakos, G.; Alexiou, P.; Antoniou, C.; Papadopoulos, G.; Stamoulis, K.E.; Valsami, S. Economic crisis in Greece: The invisible enemy of blood donation or not? Transfus. Apher. Sci. Off. J. World Apher. Assoc. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Haemapheresis 2022, 61, 103467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortis, S.P.; Dryllis, G.; Anastasiadi, A.T.; Tzounakas, V.L.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Georgatzakou, H.T.; Pavlou, E.G.; Tsantes, A.G.; Theodorogianni, V.; Kosma, M.A.; et al. Unveiling the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on blood donation patterns: A Greek perspective. Transfus. Apher. Sci. Off. J. World Apher. Assoc. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Haemapheresis 2025, 64, 104122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Blood Safety and Availability; World Health Organization Fact Sheet; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Connecting Communities, Improving Healthcare, Changing Lives. Available online: https://americasblood.org/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Murphy, W.G. The sex difference in haemoglobin levels in adults—Mechanisms, causes, and consequences. Blood Rev. 2014, 28, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantadakis, E.; Panagopoulou, P.; Kontekaki, E.; Bezirgiannidou, Z.; Martinis, G. Iron Deficiency and Blood Donation: Links, Risks and Management. J. Blood Med. 2022, 13, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadler, S.B.; Hidalgo, J.H.; Bloch, T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery 1962, 51, 224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Prados Madrona, D.; Fernández Herrera, M.D.; Prados Jiménez, D.; Gómez Giraldo, S.; Robles Campos, R. Women as whole blood donors: Offers, donations and deferrals in the province of Huelva, south-western Spain. Blood Transfus. 2014, 12 (Suppl. S1), s11–s20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelburg, R.A.; van Stein, D.; Briët, E.; van der Bom, J.G. The role of donor antibodies in the pathogenesis of transfusion-related acute lung injury: A systematic review. Transfusion 2008, 48, 2167–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.; Chawla, A.; Tucker, R.; Vohr, B. Impact of Blood Donor Sex on Transfusion-Related Outcomes in Preterm Infants. J. Pediatr. 2018, 201, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, R.G.; Glynn, S.A.; Kiss, J.E.; Mast, A.E.; Steele, W.R.; Murphy, E.L.; Wright, D.J.; Sacher, R.A.; Gottschall, J.L.; Tobler, L.H.; et al. Iron deficiency in blood donors: The REDS-II Donor Iron Status Evaluation (RISE) study. Transfusion 2012, 52, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.R.; Mast, A.E. Iron status of blood donors. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2022, 29, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Guide to the Preparation, Use and Quality Assurance of Blood Components; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM): Strasbourg, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tzounakas, V.L.; Kriebardis, A.G.; Papassideri, I.S.; Antonelou, M.H. Donor-variation effect on red blood cell storage lesion: A close relationship emerges. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2016, 10, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Sjölander, A.; Edgren, G. Mortality Among Patients Undergoing Blood Transfusion in Relation to Donor Sex and Parity: A Natural Experiment. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutler, E.; West, C. Hematologic differences between African-Americans and whites: The roles of iron deficiency and α-thalassemia on hemoglobin levels and mean corpuscular volume. Blood 2005, 106, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Nemkov, T.; Sun, K.; Liu, H.; Song, A.; Monte, A.A.; Subudhi, A.W.; Lovering, A.T.; Dvorkin, D.; Julian, C.G.; et al. AltitudeOmics: Red Blood Cell Metabolic Adaptation to High Altitude Hypoxia. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 3883–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, T.; Guo, J.; Zhao, T.; Tang, H.; Dong, F.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Tang, M. Sex differences in erythrocyte fatty acid composition of first-diagnosed, drug-naïve patients with major depressive disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1314151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, K.; Kinoshita, Y.; Nishio, I. Synergistic role of progesterone and nitric oxide in the regulation of membrane fluidity of erythrocytes in humans: An electron paramagnetic resonance investigation. Am. J. Hypertens. 2002, 15, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fang, F.; Hazegh, K.; Sinchar, D.; Guo, Y.; Page, G.P.; Mast, A.E.; Kleinman, S.; Busch, M.P.; Kanias, T. Sex hormone intake in female blood donors: Impact on haemolysis during cold storage and regulation of erythrocyte calcium influx by progesterone. Blood Transfus. 2019, 17, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Hirakawa, R.; Ochiai, H. Correlation between sphingomyelin and the membrane stability of mammalian erythrocytes. Comp. Biochem. physiology. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 265, 110833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Ishimatu, T. Effects of Cholesterol on Membrane Stability of Human Erythrocytes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 43, 1604–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshalani, A.; Li, W.; Juffermans, N.P.; Seghatchian, J.; Acker, J.P. Biological mechanisms implicated in adverse outcomes of sex mismatched transfusions. Transfus. Apher. Sci. Off. J. World Apher. Assoc. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Haemapheresis 2019, 58, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acker, J.P.; Marks, D.C.; Sheffield, W.P. Quality Assessment of Established and Emerging Blood Components for Transfusion. J. Blood Transfus. 2016, 2016, 4860284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.R. Red cell storage. J. Proteom. 2010, 73, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mykhailova, O.; Olafson, C.; Turner, T.R.; D’Alessandro, A.; Acker, J.P. Donor-dependent aging of young and old red blood cell subpopulations: Metabolic and functional heterogeneity. Transfusion 2020, 60, 2633–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doctor, A.; Spinella, P. Effect of Processing and Storage on Red Blood Cell Function In Vivo. Semin. Perinatol. 2012, 36, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, R.T. Red Cell Membrane Changes During Storage. Transfus. Med. Rev. 1988, 2, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzounakas, V.L.; Karadimas, D.G.; Anastasiadi, A.T.; Georgatzakou, H.T.; Kazepidou, E.; Moschovas, D.; Velentzas, A.D.; Kriebardis, A.G.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. Donor-specific individuality of red blood cell performance during storage is partly a function of serum uric acid levels. Transfusion 2018, 58, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.; Hazegh, K.; Fang, F.; Sinchar, D.; Kiss, J.E.; Page, G.P.; D’Alessandro, A.; Kanias, T. Testosterone replacement therapy in blood donors modulates erythrocyte metabolism and susceptibility to hemolysis in cold storage. Transfusion 2021, 61, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, G.P.; Kanias, T.; Guo, Y.J.; Lanteri, M.C.; Zhang, X.; Mast, A.E.; Cable, R.G.; Spencer, B.R.; Kiss, J.E.; Fang, F.; et al. Multiple-ancestry genome-wide association study identifies 27 loci associated with measures of hemolysis following blood storage. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e146077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.O.; D’Alessandro, A.; Eisenberger, A.; Soffing, M.; Yeh, R.; Coronel, E.; Sheikh, A.; Rapido, F.; La Carpia, F.; Reisz, J.A.; et al. Donor glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency decreases blood quality for transfusion. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2270–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karafin, M.S.; Francis, R.O. Impact of G6PD status on red cell storage and transfusion outcomes. Blood Transfus. 2019, 17, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshkelgosha, S.; Reza Deyhim, M.; Ali Khavari-Nejad, R.; Meschi, M. Comparative evaluation of oxidative and biochemical parameters of red cell concentrates (RCCs) prepared from G6PD deficient donors and healthy donors during RCC storage. Transfus. Clin. Biol. J. Soc. Fr. Transfus. Sang. 2024, 31, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisz, J.A.; Tzounakas, V.L.; Nemkov, T.; Voulgaridou, A.I.; Papassideri, I.S.; Kriebardis, A.G.; D’Alessandro, A.; Antonelou, M.H. Metabolic Linkage and Correlations to Storage Capacity in Erythrocytes from Glucose 6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase-Deficient Donors. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshalani, A.; AlSudais, H.; Binhassan, S.; Juffermans, N.P. Sex discrepancies in blood donation: Implications for red blood cell characteristics and transfusion efficacy. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2024, 63, 104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, G.J.; Werre, J.M.; Willekens, F.L.; Novotný, V.M. Erythrocyte ageing in vivo and in vitro: Structural aspects and implications for transfusion. Transfus. Med. 2008, 18, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; McGregor, A.J. Sex- and Gender-Related Factors in Blood Product Transfusions. Gend. Genome 2020, 4, 2470289720948064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccoli, L.; Rossi, V.; Leoncini, S.; Signorini, C.; Blanco-Garcia, J.; Aldinucci, C.; Buonocore, G.; Comporti, M. Iron release, superoxide production and binding of autologous IgG to band 3 dimers in newborn and adult erythrocytes exposed to hypoxia and hypoxia-reoxygenation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gen. Subj. 2004, 1672, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisz, J.A.; Wither, M.J.; Dzieciatkowska, M.; Nemkov, T.; Issaian, A.; Yoshida, T.; Dunham, A.J.; Hill, R.C.; Hansen, K.C.; D’Alessandro, A. Oxidative modifications of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase regulate metabolic reprogramming of stored red blood cells. Blood 2016, 128, e32–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatova, O.V.; Sidorenko, A.A.; Agarkova, S.A. Effects of age and sex on rheological properties of blood. Hum. Physiol. 2015, 41, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Chen, D.; Yi, Q.-L.; Kanias, T.; Gladwin, M.T.; Acker, J.P. Assessing the influence of component processing and donor characteristics on quality of red cell concentrates using quality control data. Vox Sang. 2016, 111, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanias, T.; Sinchar, D.; Osei-Hwedieh, D.; Baust, J.J.; Jordan, A.; Zimring, J.C.; Waterman, H.R.; de Wolski, K.S.; Acker, J.P.; Gladwin, M.T. Testosterone-dependent sex differences in red blood cell hemolysis in storage, stress, and disease. Transfusion 2016, 56, 2571–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubinian, N.H.; Plimier, C.; Woo, J.P.; Lee, C.; Bruhn, R.; Liu, V.X.; Escobar, G.J.; Kleinman, S.H.; Triulzi, D.J.; Murphy, E.L.; et al. Effect of donor, component, and recipient characteristics on hemoglobin increments following red blood cell transfusion. Blood 2019, 134, 1003–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Akker, T.A.; Friedman, M.T. The history of transfusion related acute lung injury: How we got to where we are today. Ann. Blood. 2024, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Mo, C.; Zheng, L.; Gao, F.; Xue, F.; Zheng, X. Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury: From Mechanistic Insights to Therapeutic Strategies. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2413364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzieciatkowska, M.; D’Alessandro, A.; Hill, R.C.; Hansen, K.C. Plasma QconCATs reveal a gender-specific proteomic signature in apheresis platelet plasma supernatants. J. Proteom. 2015, 120, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, G.; Wu, O.; van Hylckama Vlieg, A.; Folsom, A.; Rosendaal, F.; Woodward, M. Plasma levels of coagulation factors VIII and IX and risk of venous thromboembolism: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb. Res. 2023, 229, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, S.; Brito, J.P.; Cunningham, G.R.; Hayes, F.J.; Hodis, H.N.; Matsumoto, A.M.; Snyder, P.J.; Swerdloff, R.S.; Wu, F.C.; Yialamas, M.A. Testosterone Therapy in Men with Hypogonadism: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 1715–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabetta, A.; Lombardi, L.; Stefanini, L. Sex differences at the platelet–vascular interface. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Wu, C.; Yu, S.; Ren, H.; Yin, X.; Zu, R.; Rao, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Wu, R.; et al. PlateletBase: A Comprehensive Knowledgebase for Platelet Research and Disease Insights. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2025, 23, qzaf031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.R.; Moore, E.E.; Kelher, M.R.; Samuels, J.M.; Cohen, M.J.; Sauaia, A.; Banerjee, A.; Silliman, C.C.; Peltz, E.D. Female platelets have distinct functional activity compared with male platelets: Implications in transfusion practice and treatment of trauma-induced coagulopathy. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2019, 87, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadley, J.B.; Kelher, M.R.; D’Alessandro, A.; Gamboni, F.; Hansen, K.; Coleman, J.; Jones, K.; Cohen, M.; Moore, E.E.; Banerjee, A.; et al. A pilot study of the metabolic profiles of apheresis platelets modified by donor age and sex and in vitro short-term incubation with sex hormones. Transfusion 2022, 62, 2596–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelburg, R.A.; Briët, E.; van der Bom, J.G. Mortality after transfusions, relation to donor sex. Vox Sang. 2011, 101, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassé, M.; Tinmouth, A.; English, S.W.; Acker, J.P.; Wilson, K.; Knoll, G.; Shehata, N.; van Walraven, C.; Forster, A.J.; Ramsay, T.; et al. Association of Blood Donor Age and Sex with Recipient Survival After Red Blood Cell Transfusion. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgren, G.; Ullum, H.; Rostgaard, K.; Erikstrup, C.; Sartipy, U.; Holzmann, M.J.; Nyrén, O.; Hjalgrim, H. Association of Donor Age and Sex with Survival of Patients Receiving Transfusions. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caram-Deelder, C.; Kreuger, A.L.; Evers, D.; de Vooght, K.M.K.; van de Kerkhof, D.; Visser, O.; Péquériaux, N.C.V.; Hudig, F.; Zwaginga, J.J.; van der Bom, J.G.; et al. Association of Blood Transfusion from Female Donors With and Without a History of Pregnancy with Mortality Among Male and Female Transfusion Recipients. JAMA 2017, 318, 1471–1478, Erratum in JAMA 2018, 319, 724. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, M.P.; Rochwerg, B.; Jamula, E.; Li, N.; Hillis, C.; Acker, J.P.; Runciman, R.J.R.; Lane, S.J.; Ahmed, N.; Arnold, D.M.; et al. Sex-mismatched red blood cell transfusions and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vox Sang. 2019, 114, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarets, M.; Bardiaux, L.; Benzenine, E.; Dussaucy, A.; Binda, D.; Tiberghien, P.; Quantin, C.; Monnet, E. Effect of storage time and donor sex of transfused red blood cells on 1-year survival in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: An observational study. Transfusion 2016, 56, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjursten, H.; Dardashti, A.; Björk, J.; Wierup, P.; Algotsson, L.; Ederoth, P. Transfusion of sex-mismatched and non-leukocyte-depleted red blood cells in cardiac surgery increases mortality. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 152, 223–232.e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshalani, A.; Uhel, F.; Cremer, O.L.; Schultz, M.J.; de Vooght, K.M.K.; van Bruggen, R.; Acker, J.P.; Juffermans, N.P. Donor-recipient sex is associated with transfusion-related outcomes in critically ill patients. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 3260–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Lucier, K.J.; Heddle, N.M.; Acker, J.P. The association of donor and recipient sex on sepsis rates and hemoglobin increment among critically ill patients receiving red cell transfusions in a retrospective study. eJHaem 2025, 6, e1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshalani, A.; van Manen, L.; Boshuizen, M.; van Bruggen, R.; Acker, J.P.; Juffermans, N.P. The Effect of Sex-Mismatched Red Blood Cell Transfusion on Endothelial Cell Activation in Critically Ill Patients. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2021, 49, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun-Rasmussen, P.; Andersen, P.K.; Banasik, K.; Brunak, S.; Johansson, P.I. Estimating the effect of donor sex on red blood cell transfused patient mortality: A retrospective cohort study using a targeted learning and emulated trials-based approach. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 51, 101628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, M.B.; Guenay, S.; Lohmann, A.; Henseler, O.; Heiden, M.; Hanschmann, K.M.O.; Keller-Stanislawski, B. Benefit of transfusion-related acute lung injury risk-minimization measures—German haemovigilance data (2006–2010). Vox Sang. 2012, 102, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton-Maggs, P.H.; Cohen, H. Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) haemovigilance and progress is improving transfusion safety. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 163, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Design/Population (n) | Male Recipient from Female Donor (F→M) | Female Recipient from Male Donor (M→F) | General Sex-Mismatched (if no Detail) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middelburg 2011 [89] | Observational, NL, 31,118 recipients | Increased mortality in men ≤55 years (HR ~1.8) | No significant effect | HR ~1.2 overall (not significant) |

| Caram-Deelder 2017 [92] | Observational, NL, 31,118 recipients | Increased mortality if donor parous female (HR ~1.13 single-donor; HR ~1.08 per unit, full cohort) | No effect | – |

| Bjursten 2016 [95] | Cardiac surgery, SE, 9907 patients | Increased mortality strongest in F→M | No clear harm | HR ~1.08 per mismatched unit |

| Desmarets 2016 [94] | Cardiac surgery, FR, 2715 patients | No significant effect (adjusted HR ~0.96) | Trend toward increased mortality (HR ~2.0, not significant) | HR ~2.28 unadjusted; effect disappeared after adjustment |

| Zeller 2019 [93] | 5 observational studies, 86,737 patients | Pooled increased mortality (HR ~1.13) | Not separated | Reported as “sex-mismatched” |

| Alshalani 2021 [98] | Mechanistic, ICU, 69 patients | Higher syndecan-1 and sTM → endothelial activation | Included, but effect driven by mismatched group | Sex-mismatched group showed higher injury markers |

| Alshalani 2022 [96] | ICU, 6992 patients (403 unisex transfused) | Increased ICU mortality in F→M vs. F→F (OR 2.43) | No significant difference | Mismatched group: trend to ↑ ARDS, ↓ AKI |

| Li 2025 [97] | ICU, retrospective, ~500 patients | No mortality/sepsis effect | In women, M→F units gave larger Hb increments | No sepsis difference by donor sex |

| Bruun-Rasmussen 2022 [99] | Registry-based, causal inference analysis, SE, hundreds of thousands recipients | Not separated | Not separated | Sex-matched transfusions associated with modest survival benefit |

| Chassé 2016 [90] | Observational, CA, 30,503 recipients | Increased mortality with female donor blood, especially in male recipients | Increased risk also seen in female recipients | Effect across donor sex (HR 1.08 per female donor unit) |

| Edgren 2017 [91] | Observational, SE/DK, 968,264 recipients | No association after adjustment | No association | Null in fully adjusted models |

| Zhao 2022 [50] | Natural experiment, SE, 368,778 recipients | No survival difference (−0.1%) | No survival difference | No effect by donor sex or parity |

| Chassé 2023 [19] | RCT, CA, 8719 patients randomized | No survival difference | No survival difference | No overall effect (HR 0.98) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fortis, S.P.; Kokoris, S.; Kelepousidis, P.; Dryllis, G.; Kosma, M.-A.; Pittaras, T.; Kriebardis, A.G.; Valsami, S. When Blood Remembers Its Sex: Toward Truly Personalized Transfusion Medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 592. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120592

Fortis SP, Kokoris S, Kelepousidis P, Dryllis G, Kosma M-A, Pittaras T, Kriebardis AG, Valsami S. When Blood Remembers Its Sex: Toward Truly Personalized Transfusion Medicine. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):592. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120592

Chicago/Turabian StyleFortis, Sotirios P., Styliani Kokoris, Pavlos Kelepousidis, Georgios Dryllis, Maria-Aspasia Kosma, Theodoros Pittaras, Anastasios G. Kriebardis, and Serena Valsami. 2025. "When Blood Remembers Its Sex: Toward Truly Personalized Transfusion Medicine" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 592. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120592

APA StyleFortis, S. P., Kokoris, S., Kelepousidis, P., Dryllis, G., Kosma, M.-A., Pittaras, T., Kriebardis, A. G., & Valsami, S. (2025). When Blood Remembers Its Sex: Toward Truly Personalized Transfusion Medicine. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 592. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120592