Retaining Ligaments of the Face: Still Important in Modern Approach in Mid-Face and Neck Lift?

Abstract

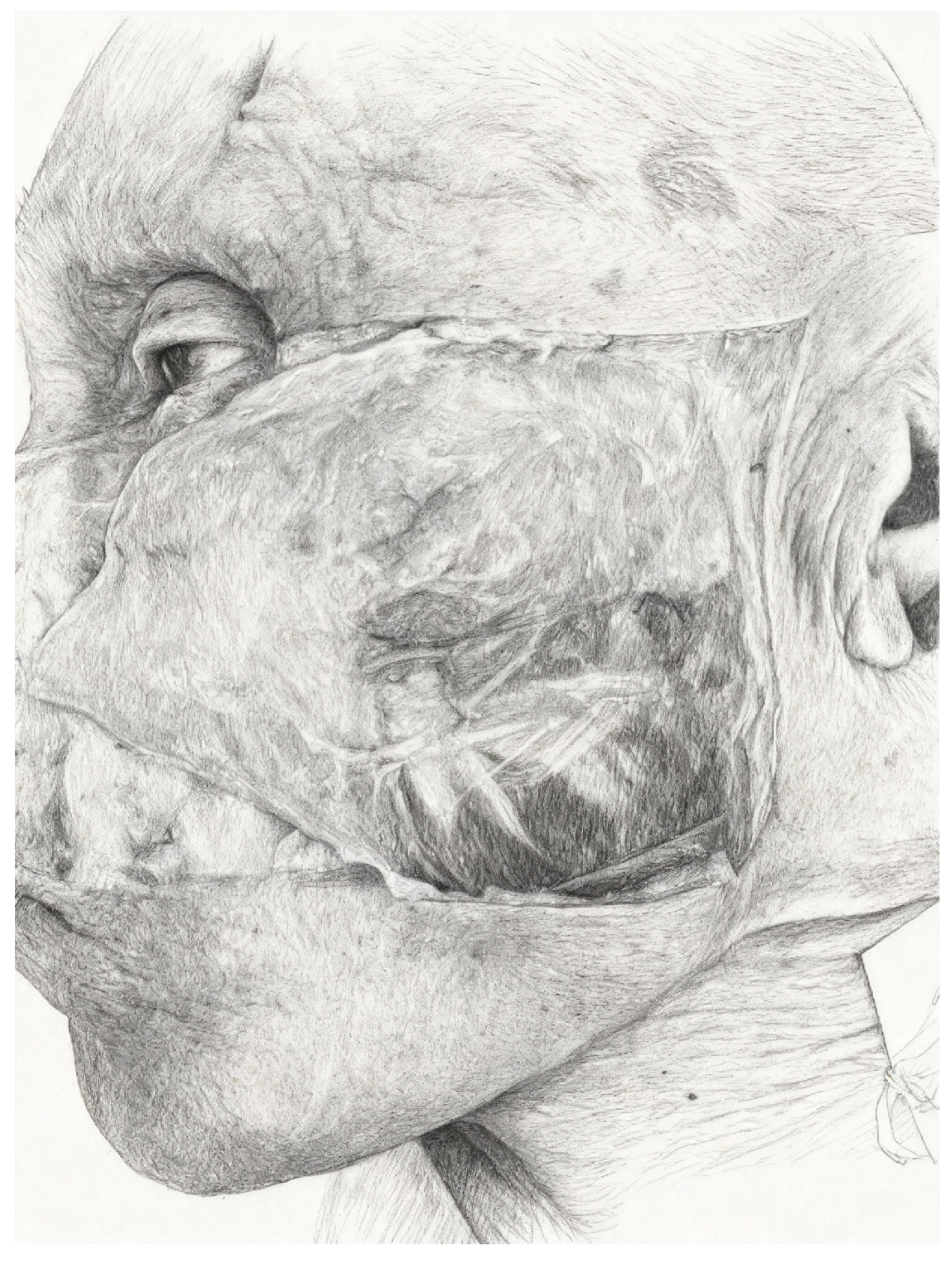

1. Introduction

2. Relevant Sections

2.1. Anatomical Overview of Retaining Ligaments

- -

- -

- Platysma auricular ligament (PAL) [4]: Described by Furnas, this ligament anchors the platysma to the skin. Later studies revised its connection to the parotid fascia.

- -

2.2. The Role of Retaining Ligaments in Aging

3. Surgical Techniques

3.1. Subcutaneous Facelift

3.2. SMAS Rhytidectomy

3.3. Minilift

3.4. Subperiosteal Facelift

3.5. Retaining Ligaments and Advanced Facelift Techniques

3.6. Ligament Preservation in Vertical Lifts

3.7. Extended Deep Plane Facelift

3.8. Vertical Facelift

3.9. PRESTO-Lift

4. Discussion

5. Resource Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

8. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGregor, M. Face Lift Techniques. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Meeting of the California Society of Plastic Surgeons, Yosemite, CA, USA; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir, R.; Kilinc, H.; Unlu, R.E.; Uysal, A.C.; Sensoz, O.; Baran, C.N. Anatomicohistologic study of the retaining ligaments of the face and use in face lift: Retaining ligament correction and SMAS plication. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2002, 110, 1134–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.S.; Song, J.K.; Oh, T.S.; Kwon, S.I.; Tansatit, T.; Lee, J.H. Review of the Nomenclature of the Retaining Ligaments of the Cheek: Frequently Confused Terminology. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2017, 44, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Furnas, D.W. The retaining ligaments of the cheek. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1989, 83, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuzin, J.M.; Baker, T.J.; Gordon, H.L. The relationship of the superficial and deep facial fascias: Relevance to rhytidectomy and aging. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1992, 89, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owsley, J.Q. Elevation of the malar fat pad superficial to the orbicularis oculi muscle for correction of prominent nasolabial folds. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1995, 22, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, B.C. Extended sub-SMAS dissection and cheek elevation. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1995, 22, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, W. Presto lift-a facelift that preserves the retaining ligaments and SMAS tethering. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 21, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jacono, A.; Bryant, L.M. Extended Deep Plane Facelift: Incorporating Facial Retaining Ligament Release and Composite Flap Shifts to Maximize Midface, Jawline and Neck Rejuvenation. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2018, 45, 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.H.; Hsieh, M.K.H.; Mendelson, B. The tear trough ligament: Anatomical basis for the tear trough deformity. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 129, 1392–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.H.; Mendelson, B.C. Facial soft tissue spaces of the midcheek: Defining the premaxillary space. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 132, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, B.C.; Freeman, M.E.; Wu, W.; Huggins, R.J. Surgical anatomy of the lower face: The premasseter space, the jowl, and the labiomandibular fold. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2008, 32, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghoul, M.; Codner, M.A. Retaining ligaments of the face: Review of anatomy and clinical applications. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2013, 33, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, K.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, Y.S. Anatomy and tensile strength of the zygomatic ligament. J. Craniofac Surg. 2001, 22, 1831–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, D.M.; Casanueva, F.J.; Wang, T.D. Evolution of the rhytidectomy. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 2, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon, M.L.; Hamra, S.T. Skoog rhytidectomy: A five-year experience with 577 patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1980, 65, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamer, F.M.; Frankel, A.S. SMAS rhytidectomy versus deep plane rhytidectomy: An objective comparison. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102, 878–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.H.; Lee, W. Minilifting: Short-Scar Rhytidectomy with Thread Lifting. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2024, 51, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, K.L. The “mini-lift”: An old wrinkle in face lifting. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1970, 46, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.J.; Gordon, H.L. The temporal face lift (“mini-lift”). Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1971, 47, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamin, C.; Laure, B. Le MASK lift [The MASK lift]. Ann. Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2024, 69, 714–720. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamra, S.T. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1990, 86, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owsley, J.Q., Jr. SMAS-platysma facelift. A bidirectional cervicofacial rhytidectomy. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1983, 10, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonnard, P.; Verpaele, A. The MACS-lift short scar rhytidectomy. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2007, 27, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacono, A.A.; Parikh, S.S.; Kennedy, W.A. Anatomical comparison of platysmal tightening using superficial musculoaponeurotic system plication vs deep-plane rhytidectomy techniques. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 2011, 13, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacono, A.A.; Bryant, L.M.; Ahmedli, N.N. A novel extended deep plane facelift technique for jawline rejuvenation and volumization. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2019, 39, 1265–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.W.; Waters, H.H. The extended SMAS approach to neck rejuvenation. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 22, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacono, A.A.; Talei, B. Vertical neck lifting. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 22, 285–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.W. Achieving the natural look in rhytidectomy. Facial Plast. Surg. 2000, 16, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.J.; Ceradini, D.J. Current Trends in Facelift and Necklift Procedures. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mortada, H.; Alkilani, N.; Halawani, I.R.; Zaid, W.A.; Alkahtani, R.S.; Saqr, H.; Neel, O.F. Evolution of Superficial Muscular Aponeurotic System Facelift Techniques: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Complications and Outcomes. JPRAS Open 2023, 39, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Minelli, L.; Brown, C.P.; van der Lei, B.; Mendelson, B. Anatomy of the Facial Glideplanes, Deep Plane Spaces, and Ligaments: Implications for Surgical and Nonsurgical Lifting procedures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 154, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuzin, J.M.; Rohrich, R.J. Facial Nerve Danger Zones. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 145, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitik, O. Sub-SMAS Reconstruction of Retaining Ligaments. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2022, 42, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.M.; Horibe, E.K. Understanding the finger-assisted malar elevation technique in face lift. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 118, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vayalapra, S.; Guerrero, D.N.; Sandhu, V.; Happy, A.; Imantalab, D.; Kissoonsingh, P.; Khajuria, A. Comparing the safety and efficacy of superficial musculoaponeurotic system and deep plane facelift techniques: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2025, 95, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.J.; Aston, S.J. Ancillary Procedures to Facelift Surgery: What has Changed? Aesthet. Surg. J. Open Forum. 2023, 5, ojad063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cakmak, O. Clarification Regarding the Modified Finger-Assisted Malar Elevation (FAME) Technique. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2019, 39, NP161–NP162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinta, S.R.; Brydges, H.T.; Laspro, M.; Shah, A.R.; Cohen, J.; Ceradini, D.J. Current Trends in Deep Plane Neck Lifting: A Systematic Review. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2025, 94, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.R.; Kennedy, P.M. The Aging Face. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 102, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Qiao, Z.; Yang, K. Different Techniques and Quantitative Measurements in Upper lip lift: A Systematic Review. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 1364–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudeh, Z.S.; Stevens, W.G. Nonsurgical Adjuncts Following Facelift to Achieve Optimal Aesthetic Outcomes: “Icing on the Cake”. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2019, 46, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, C.J.; Marcus, B. Energy-Based Facial Rejuvenation: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA Facial Plast. Surg. 2017, 19, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, S.M.; Borab, Z.; Weir, D.; Rohrich, R.J. The emerging role of biostimulators as an adjunct in facial rejuvenation: A systematic review. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2024, 92, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisniewski, J.D.; Ellis, D.L.; Lupo, M.P. Facial rejuvenation: Combining cosmeceuticals with cosmetic procedures. Cutis 2014, 94, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nahai, F.; Bassiri-Tehrani, B.; Santosa, K.B. Hematomas and the Facelift Surgeon: It’s Time for Us to Break Up for Good. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2023, 43, 1207–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanadham, S.R.; Mapula, S.; Costa, C.; Narasimhan, K.; Coleman, J.E.; Rohrich, R.J. Evolution of hypertension management in face lifting in 1089 patients: Optimizing safety and outcomes. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.M.; Grover, R. Avoiding hematoma in cervicofacial rhytidectomy: A personal 8-year quest. Reviewing 910 patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 113, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auersvald, A.; Auersvald, L.A. Hemostatic net in rhytidoplasty: An efficient and safe method for preventing hematoma in 405 consecutive patients. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2014, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Brown, T.; Rohrich, R.J. Clinical Applications of Tranexamic Acid in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 154, 1253e–1263e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElAbd, R.; Richa, Y.; Pu, L.; Hiyzajie, T.; Safran, T.; Gilardino, M. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid use in face and neck lift surgery: A systematic review. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2025, 104, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJoseph, L.M.; Pou, J.D. Local Anesthetic Facelift. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 28, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moris, V.; Bensa, P.; Gerenton, B.; Rizzi, P.; Cristofari, S.; Zwetyenga, N.; Guilier, D. The cervicofacial lift under pure local anaesthesia diminishes the incidence of post-operative haematoma. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2019, 72, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, L.; Kim, P.; Yuan, M.; Gallo, M.; Thoma, A.; Voineskos, S.H.; Cano, S.J.; Pusic, A.L.; Klassen, A.F. Best Practices for FACE-Q Aesthetics Research: A Systematic Review of Study Methodology. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2023, 43, NP674–NP686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cheek Ligaments | Synonym |

|---|---|

| MALAR AREA McGregor’s patch | Zygomatic ligament Zygomatic cutaneous ligament |

|

PERI-AURICULAR AREA Platysma auricular ligament Parotid cutaneous ligament Platysma auricular fascia Temporoparotid fascia | Auricle-platysma ligament Platysma auricular fascia Preauricular parotid cutaneous ligament Platysma auricular ligament Parotid cutaneous ligament Platysma auricular fascia Auricle-platysma ligament Preauricular parotid cutaneous ligaments Lore’s fascia Lore’s fascia Tympanoparotid fascia |

|

PERI-MASSETERIC AREA Anterior platysma-cutaneous ligament Platysma cutaneous ligament | Masseteric cutaneous ligament Parotidomasseteric cutaneous ligament Mandibular septum |

| Technique | Dissection Plane | Ligament Management | Advantages | Limitations | Primary Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous facelift | Supra-SMAS | Generally preserved | Simple technique, quick recovery | Less durable results, limited effect | Mild laxity, young patients |

| SMAS rhytidectomy | Superficial SMAS | Preserved or plicated | Better support than cutaneous technique | Limited effect on midface | Mild-moderate ptosis, middle-aged patients |

| Mini-lift | Supra-SMAS | Not manipulated | Minimally invasive, short recovery time | Limited correction, shorter duration | Mild facial laxity |

| Deep plane facelift | Sub-SMAS | Released (zygomatic, masseteric, etc.) | Natural and long-lasting results in midface | Advanced technique, higher nerve risk | Moderate-severe ptosis of midface and neck |

| Subperiosteal facelift | Subperiosteal | Released with periosteum | Effective on mid-third, deep lifting | Longer recovery, complex technique | Midface ptosis, infraorbital deformities |

| MACS-lift | Supra-SMAS with suspension | Preserved | Minimally invasive, vertical suspension | Less neck correction | Mild-moderate ptosis, good skin tone |

| Extended deep plane facelift | Extended sub-SMAS | Extensively released | Complete 3D lift, effective on neck | Requires high surgical expertise | Advanced aging, severe ptosis |

| Vertical lift | Vertical sub-SMAS | Released (zygomatic, mandibular, cervical) | Anti-gravity lift, natural result | Very precise technique, increased complication risk | Advanced midface and neck ptosis |

| PRESTO facelift | Selective supra and sub-SMAS | Preserved (except selectively released) | Preserves phenotype, natural effect | Less vertical lift effect | Patients with subtle, refined features |

| Technique | Sample Size/Follow-Up | Complications | Operator Experience/Learning Curve |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous | Historical data; limited follow-up | Hematoma, less durable results, early recurrence | Simple technique, short learning curve |

| SMAS rhytidectomy | Large series (>500 pts) | Hematoma ~2–3%, rare transient nerve injuries | Requires SMAS knowledge; moderate learning curve |

| Mini-lift | Small series; short follow-up | Low complication rates, shorter-lasting results | Simple, short learning curve |

| Subperiosteal | Specialized series; mid-long follow-up | Longer recovery, edema, higher nerve risk | Complex; long learning curve |

| Deep plane | Meta-analyses (~11,000 cases) | Hematoma ~3%, transient nerve injuries; durable outcomes | Advanced technique; long learning curve |

| Extended deep plane | Dedicated series; mid-long follow-up | Risk of buccal fat herniation, nerve damage | Very advanced, steep learning curve |

| Vertical lift | Specialized series | Similar to deep plane; risk of misplacement if inexperienced | High precision required; long curve |

| MACS lift | Medium-large series; intermediate follow-up | Low risk, rapid recovery; less neck correction | Simpler; short-medium curve |

| PRESTO lift | Initial series (Funk 2017) [8] | Minimal complications, natural results; less vertical effect | Newer approach; learning curve evolving |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarallo, M.; Cilluffo, M.; Papa, F.; Fanelli, B. Retaining Ligaments of the Face: Still Important in Modern Approach in Mid-Face and Neck Lift? J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120582

Tarallo M, Cilluffo M, Papa F, Fanelli B. Retaining Ligaments of the Face: Still Important in Modern Approach in Mid-Face and Neck Lift? Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):582. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120582

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarallo, Mauro, Matteo Cilluffo, Francesco Papa, and Benedetta Fanelli. 2025. "Retaining Ligaments of the Face: Still Important in Modern Approach in Mid-Face and Neck Lift?" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120582

APA StyleTarallo, M., Cilluffo, M., Papa, F., & Fanelli, B. (2025). Retaining Ligaments of the Face: Still Important in Modern Approach in Mid-Face and Neck Lift? Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120582