Baseline Findings from Dual-Phase Amyloid PET Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Sclerosis: Exploring Its Potential as a Biomarker of Myelination and Neurodegeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Population, and Sample Size Estimation

2.2. Clinical and Cognitive Assessments

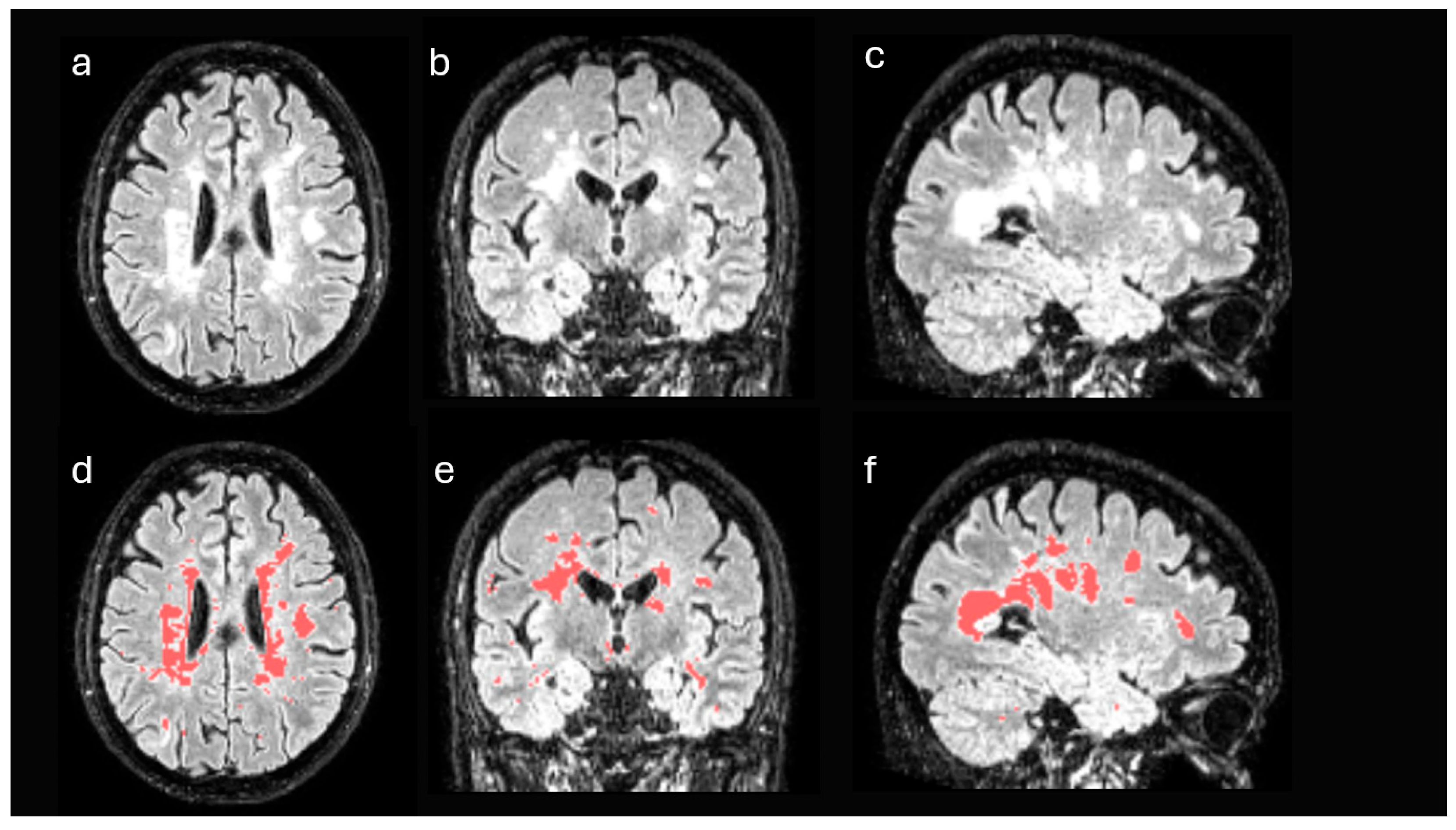

2.3. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging

2.4. Positron Emission Tomography with [18F]Florbetaben

2.5. Neuroimaging Pre-Processing and Analysis

- SUVmax (maximum standardized uptake value): The highest SUV value within a defined region of interest (ROI). It reflects the point of greatest radiotracer uptake and is commonly used as an indicator of peak metabolic activity.

- SUVmean (mean standardized uptake value): The mean SUV within the ROI represents the average value of all voxel SUV measurements. It provides a robust measurement that is less influenced by outliers compared to SUVmax.

- SUVmin (minimum standardized uptake value): The lowest SUV value within the ROI. While less frequently used on its own, it can be helpful in assessing areas of low tracer uptake or evaluating lesion heterogeneity.

- SUVR (SUV relative to the cerebellum): Ratio using the cerebellum as the reference region.

- % of change SUV: Percentage of change between the DWM and NAWM calculated, according to previous studies, as follows: the DWM uptake minus NAWM uptake, divided by the NAWM uptake and multiplied by 100 [9].

2.6. Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Clinical and Neuroimaging Characteristics

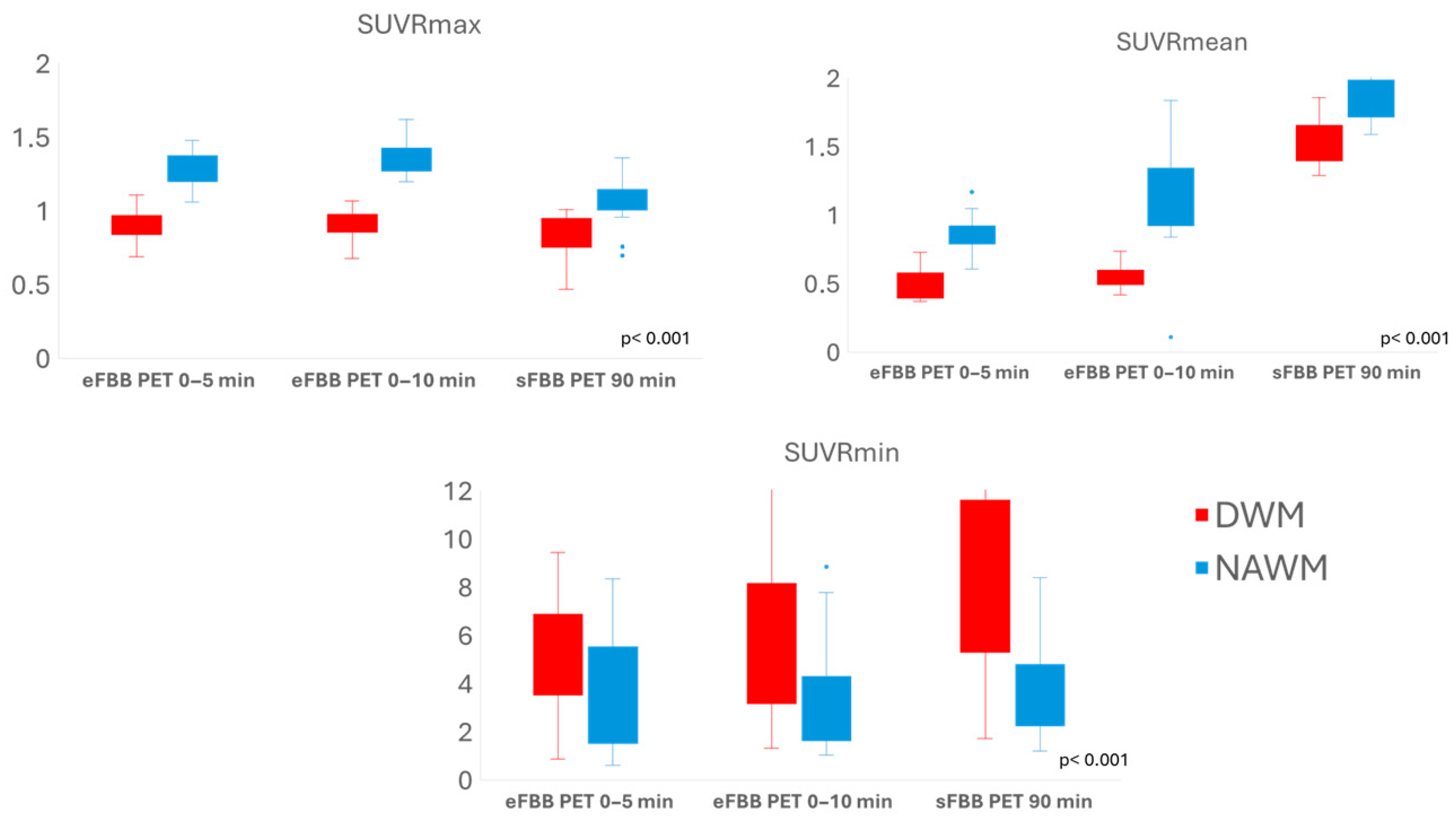

3.2. Comparison of Tracer Uptake Intensity in DWM Versus NAWM

3.3. Comparison of SUVR Values in DWM and NAWM Between Early and Late FBB PET Phases

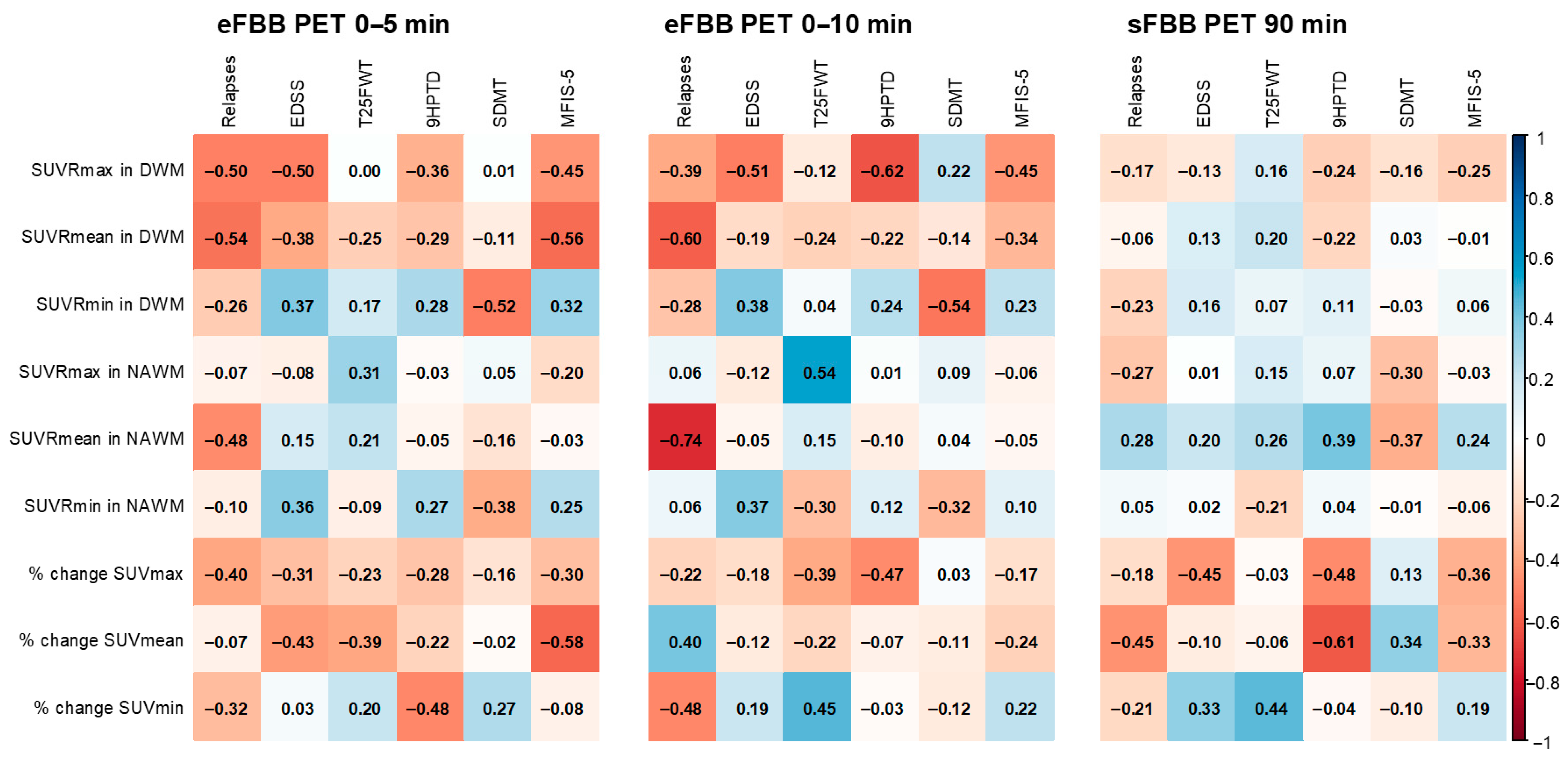

3.4. Correlations Between FBB PET Quantitative Parameters and Clinical/Neuropsychological Scales

4. Discussion

4.1. Myelination and Neurodegeneration

4.2. Early Phase of Amyloid PET

4.3. Correlation with Clinical Variables Related to Disease Activity and Progression

4.4. Study Strengths

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | Amyloid-β1-42 oligomers | NAWM | Normal-appearing white matter |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory-II | PET | Positron emission tomography |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid | RRMS | Relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis |

| CVLT | California Verbal Learning Test | sFBB | Standard acquisition [18F]florbetaben |

| DWM | Damaged white matter | SMDT | Symbol Digit Modalities Test |

| EDSS | Expanded Disability Status Scale | SUV | Standardized uptake value |

| eFBB | Early acquisition [18F]florbetaben | SUVmax | Maximum standardized uptake value |

| EQ-5D | EuroQoL-5D | SUVmean | Mean standardized uptake value |

| FBB | [18F]florbetaben | SUVmin | Minimum standardized uptake value |

| GM | Gray matter | SUVR | Standardized uptake value relative to the cerebellum |

| MFIS-5 | Modified Fatigue Impact Scale 5-item Version | T25FW | The Timed 25-Foot Walk |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging | 9HPT | The Nine-Hole Peg Test |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis | % of change SUV | Percentage of change between SUV of DWM and NAWM |

References

- McGinley, M.P.; Goldschmidt, C.H.; Rae-Grant, A.D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaliunas, A.; Danylaitė Karrenbauer, V.; Binzer, S.; Hillert, J. Systematic Review of the Socioeconomic Consequences in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis with Different Levels of Disability and Cognitive Function. Front. Neurol. 2022, 12, 737211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tur, C.; Carbonell-Mirabent, P.; Cobo-Calvo, Á.; Otero-Romero, S.; Arrambide, G.; Midaglia, L.; Castilló, J.; Vidal-Jordana, Á.; Rodríguez-Acevedo, B.; Zabalza, A.; et al. Association of Early Progression Independent of Relapse Activity with Long-Term Disability after a First Demyelinating Event in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absinta, M.; Lassmann, H.; Trapp, B.D. Mechanisms Underlying Progression in Multiple Sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2020, 33, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inojosa, H.; Schriefer, D.; Ziemssen, T. Clinical Outcome Measures in Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkert, P.; Meier, S.; Schaedelin, S.; Manouchehrinia, A.; Yaldizli, Ö.; Maceski, A.; Oechtering, J.; Achtnichts, L.; Conen, D.; Derfuss, T.; et al. Serum Neurofilament Light Chain for Individual Prognostication of Disease Activity in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Retrospective Modelling and Validation Study. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, M.A.; Valsasina, P.; Meani, A.; Gobbi, C.; Zecca, C.; Barkhof, F.; Schoonheim, M.M.; Strijbis, E.M.; Vrenken, H.; Gallo, A.; et al. Spinal Cord Lesions and Brain Grey Matter Atrophy Independently Predict Clinical Worsening in Definite Multiple Sclerosis: A 5-Year, Multicentre Study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2022, 94, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertcoff, A.; Schneider, R.; Azevedo, C.J.; Sicotte, N.; Oh, J. Recent Advances in Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Disease-Monitoring Biomarkers in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurol. Clin. 2024, 42, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matías-Guiu, J.A.; Cabrera-Martín, M.N.; Matías-Guiu, J.; Oreja-Guevara, C.; Riola-Parada, C.; Moreno-Ramos, T.; Arrazola, J.; Carreras, J.L. Amyloid PET Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis: An 18F-Florbetaben Study. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, A.; LaPlante, N.E.; Cotero, V.E.; Fish, K.M.; Bjerke, R.M.; Siclovan, T.; Tan Hehir, C.A. Identification of the Protein Target of Myelin-Binding Ligands by Immunohistochemistry and Biochemical Analyses. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2013, 61, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankoff, B.; Freeman, L.; Aigrot, M.S.; Chardain, A.; Dollé, F.; Williams, A.; Galanaud, D.; Armand, L.; Lehericy, S.; Lubetzki, C.; et al. Imaging Central Nervous System Myelin by Positron Emission Tomography in Multiple Sclerosis Using [Methyl-11C]-2-(4-Methylaminophenyl)- 6-Hydroxybenzothiazole. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodini, B.; Veronese, M.; Turkheimer, F.; Stankoff, B. Benzothiazole and Stilbene Derivatives as Promising Positron Emission Tomography Myelin Radiotracers for Multiple Sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 80, 166–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietroboni, A.M.; Carandini, T.; Colombi, A.; Mercurio, M.; Ghezzi, L.; Giulietti, G.; Scarioni, M.; Arighi, A.; Fenoglio, C.; De Riz, M.A.; et al. Amyloid PET as a Marker of Normal-Appearing White Matter Early Damage in Multiple Sclerosis: Correlation with CSF β-Amyloid Levels and Brain Volumes. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ni, Y.; Zhou, Q.; He, L.; Meng, H.; Gao, Y.; Huang, X.; Meng, H.; Li, P.; Chen, M.; et al. 18F-Florbetapir PET/MRI for Quantitatively Monitoring Myelin Loss and Recovery in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Longitudinal Study. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 37, 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pytel, V.; Matias-Guiu, J.A.; Matías-Guiu, J.; Cortés-Martínez, A.; Montero, P.; Moreno-Ramos, T.; Arrazola, J.; Carreras, J.L.; Cabrera-Martín, M.N. Amyloid PET Findings in Multiple Sclerosis Are Associated with Cognitive Decline at 18 Months. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 39, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecchi, E.; Veronese, M.; Bodini, B.; García-Lorenzo, D.; Battaglini, M.; Stankoff, B.; Turkheimer, F.E. Multimodal Partial Volume Correction: Application to [11C]PIB PET/MRI Myelin Imaging in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 3803–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: 2017 Revisions of the McDonald Criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potticary, H.; Langdon, D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Brief Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS) International Validations. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPM Software—Statistical Parametric Mapping. Available online: https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Tzourio-Mazoyer, N.; Landeau, B.; Papathanassiou, D.; Crivello, F.; Etard, O.; Delcroix, N.; Mazoyer, B.; Joliot, M. Automated Anatomical Labeling of Activations in SPM Using a Macroscopic Anatomical Parcellation of the MNI MRI Single-Subject Brain. Neuroimage 2002, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolls, E.T.; Huang, C.C.; Lin, C.P.; Feng, J.; Joliot, M. Automated Anatomical Labelling Atlas 3. Neuroimage 2020, 206, 116189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, D.S.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Calabresi, P.A. Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matías-Guiu, J.A.; Oreja-Guevara, C.; Cabrera-Martín, M.N.; Moreno-Ramos, T.; Carreras, J.L.; Matías-Guiu, J. Amyloid Proteins and Their Role in Multiple Sclerosis. Considerations in the Use of Amyloid-PET Imaging. Front. Neurol. 2016, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvity, S.; Tonietto, M.; Caillé, F.; Bodini, B.; Bottlaender, M.; Tournier, N.; Kuhnast, B.; Stankoff, B. Repurposing Radiotracers for Myelin Imaging: A Study Comparing 18F-Florbetaben, 18F-Florbetapir, 18F-Flutemetamol,11C-MeDAS, and 11C-PiB. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2020, 47, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.; Tayebi, M. Detection of Protein Aggregates in Brain and Cerebrospinal Fluid Derived from Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyka-Fościak, G.; Jasek-Gajda, E.; Wójcik, B.; Lis, G.J.; Litwin, J.A. Tau Protein and β-Amyloid Associated with Neurodegeneration in Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein-Induced Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE), a Mouse Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A. Role of Amyloid from a Multiple Sclerosis Perspective: A Literature Review. Neuroimmunomodulation 2015, 22, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietroboni, A.M.; Caprioli, M.; Carandini, T.; Scarioni, M.; Ghezzi, L.; Arighi, A.; Cioffi, S.; Cinnante, C.; Fenoglio, C.; Oldoni, E.; et al. CSF β-Amyloid Predicts Prognosis in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2019, 25, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, M.S.; Garofalo, S.; Marfia, G.A.; Gilio, L.; Simonelli, I.; Finardi, A.; Furlan, R.; Sancesario, G.M.; Di Giandomenico, J.; Storto, M.; et al. Amyloid-β Homeostasis Bridges Inflammation, Synaptic Plasticity Deficits and Cognitive Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, F.; Gómez-Río, M.; Sánchez-Vañó, R.; Górriz, J.M.; Ramírez, J.; Triviño-Ibáñez, E.; Carnero-Pardo, C.; Martínez-Lozano, M.D.; Sopena-Novales, P. Usefulness of Dual-Point Amyloid PET Scans in Appropriate Use Criteria: A Multicenter Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 65, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojo-Ramírez, J.A.; Fernández-Rodríguez, P.; Guerra-Gómez, M.; Marín-Cabañas, A.M.; Franco-Macías, E.; Jiménez-Hoyuela-García, J.M.; García-Solís, D. Evaluation of Early-Phase 18F-Florbetaben PET as a Surrogate Biomarker of Neurodegeneration: In-Depth Comparison with 18F-FDG PET at Group and Single Patient Level. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 106, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic (n = 20) | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| MS onset age (y) | 35.05 (10.72) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 5 (25) |

| Female | 15 (75) |

| Initial clinical presentation | |

| Optic neuritis | 6 (30) |

| Myelitis | 7 (35) |

| Hemispheric syndrome | 2 (10) |

| Brainstem syndrome | 5 (25) |

| N° of relapses | 1.95 (1.15) |

| EDSS score | 1.90 (1.09) |

| Other progression disease scales | |

| T25FW (s) | 5.62 (1.19) |

| 9HPT-D (s) | 23.66 (5.06) |

| 9HPT-ND (seconds) | 24.07 (3.49) |

| Fatigue: MFIS-5 score | 8.95 (6.37) |

| Cognitive functions | |

| SDMT (z-score) | −1.13 (0.96) |

| CVLT-II (z-score) | −1.35 (1.18) |

| BVMT (z-score) | −0.68 (1.51) |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II (points) | 16.55 (12.97) |

| Quality of life: EQ-5D (points) | 68.75 (22.35) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barrios-López, J.M.; Triviño-Ibáñez, E.M.; Piñeiro-Donis, A.; Segovia-Román, F.; Pérez García, M.d.C.; Marín-Romero, B.; Romero Villarrubia, A.; Guillén Martínez, V.; Martínez-Barbero, J.P.; Piñar Morales, R.; et al. Baseline Findings from Dual-Phase Amyloid PET Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Sclerosis: Exploring Its Potential as a Biomarker of Myelination and Neurodegeneration. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15110520

Barrios-López JM, Triviño-Ibáñez EM, Piñeiro-Donis A, Segovia-Román F, Pérez García MdC, Marín-Romero B, Romero Villarrubia A, Guillén Martínez V, Martínez-Barbero JP, Piñar Morales R, et al. Baseline Findings from Dual-Phase Amyloid PET Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Sclerosis: Exploring Its Potential as a Biomarker of Myelination and Neurodegeneration. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(11):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15110520

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarrios-López, José María, Eva María Triviño-Ibáñez, Adrián Piñeiro-Donis, Fermín Segovia-Román, María del Carmen Pérez García, Bartolomé Marín-Romero, Ana Romero Villarrubia, Virginia Guillén Martínez, José Pablo Martínez-Barbero, Raquel Piñar Morales, and et al. 2025. "Baseline Findings from Dual-Phase Amyloid PET Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Sclerosis: Exploring Its Potential as a Biomarker of Myelination and Neurodegeneration" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 11: 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15110520

APA StyleBarrios-López, J. M., Triviño-Ibáñez, E. M., Piñeiro-Donis, A., Segovia-Román, F., Pérez García, M. d. C., Marín-Romero, B., Romero Villarrubia, A., Guillén Martínez, V., Martínez-Barbero, J. P., Piñar Morales, R., Barrero Hernández, F. J., Mínguez-Castellanos, A., & Gómez-Río, M. (2025). Baseline Findings from Dual-Phase Amyloid PET Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Sclerosis: Exploring Its Potential as a Biomarker of Myelination and Neurodegeneration. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(11), 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15110520