A Grounded Theory of Interdisciplinary Communication and Collaboration in the Outpatient Setting of the Hospital for Patients with Multiple Long-Term Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Ethical Approval

3. Results

A Theory of Interdisciplinary Communication and Collaboration in the Outpatient Setting of the Hospital for Patients with Multiple Long-Term Conditions

- Component 1: The pathways of Interdisciplinary communication and collaboration

- I.

- Reasons for interdisciplinary communication and collaboration

“The primary care physician refers the patient to me [geriatrician], to assess the patient because of a multitude of problems. I run into complications of lung cancer and other comorbidities and start diagnostics and treatments. Simultaneously, the pulmonologist refers to the internists and the gastroenterologist to treat the same complications of lung cancer. Now, we have three people taking the lead on the same issues”

“The reason we sometimes, I think, make decisions with too little foundation, is that we see a high number of patients during short consultations. (…) Too often we assume that others, who refer the patient to us, have assessed whether the surgery is in line with the patient goals and values.”

“It [a multidisciplinary team meeting] gave them [patient and partner] a sense of peace, confidence that we are truly contemplating her problems, that we’re not abandoning them. We were able to confirm together as a care team that we don’t know all the answers yet. (…) She is now willing to wait and see how it goes.”

- II.

- Timing of interdisciplinary communication and collaboration

“It’s like ‘oh, something is wrong’, and now I must consult the internist, or the pulmonologist, or immunologist, or whatever. You notice it by chance because the patient is visiting your outpatient clinic at that time.”

- III.

- Mode of interdisciplinary communication and collaboration

- IV.

- Outcome of interdisciplinary communication and collaboration

“It is essential to involve the primary care physician in the discussion concerning advance care planning, but also to discuss which tasks the primary care physician is responsible for.”

“It can be good for patients to hear the same story from different people. (…) A patient sometimes needs that, especially when there are many factors at play and a lot of pain.”

“She [the patient] has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder and a cognitive disability. What does that mean for her? What do we need to consider? In hindsight these are things I would have liked to know.”

“The most important thing is that we didn’t operate the aneurysm and avoided looking back saying ‘mm, should we have done that…’. In that regard, it’s not too bad, but in terms of burden, hospital visits, diagnostics… those things we could have avoided for him if we approached it in an interdisciplinary way sooner.”

- V.

- Goal of interdisciplinary communication and collaboration

“You should always try to tailor care to comorbidities, psychosocial context, and the goals, values, and priorities of the patient. It doesn’t matter if you’re the only treating physician or if there are many. And then it depends if it is necessary for this specific patient to gather everyone around a table for a discussion or if a more informal way of collaboration suffices. Like oh, I’m seeing this patient, my plan is this and that, does that align with your plan and goals?”

- Component 2: Internalized Rules of HCPs

“Care coordination by a pulmonologist-oncologist is fine, but they should not meddle with heart failure medication. (…) Giving up control like that is not something easily done within my specialty.”

“Of course, there are a few general specializations, such as internists and geriatricians, but that’s about it. All other specialists work solely from the perspective of their specialization and sub-specialization.”

“What makes the system very fragile, is that it is very dependent on who the patient visits first in the hospital. (….) I think that many specialists, they don’t feel inclined to claim a care coordinator role, they don’t feel equipped, or they don’t have time.”

“Once a referral has been made, then, apparently, a general practitioner or a nursing home doctor is also in a difficult situation because of a family who believes ‘grandma should live until 100’ or whatever it may be. And then there’s unrest, and they come to us, and then you have to proceed.”

“I have two or three neurologists and a few cardiologists specialized in heart rhythm disorders that I can call. And well, among the internist, there are a few that I can approach.”

- Component 3: Organizational structures of influence

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rijken, M.; Struckmann, V.; van der Heide, I.; Hujala, A.; Barbabella, F.; van Ginneken, E.; On behalf of the ICARE4EU consortium. In How to Improve Care for People with Multimorbidity in Europe? World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Volksgezondheid en Zorg. Available online: https://www.vzinfo.nl/chronische-aandoeningen-en-multimorbiditeit/leeftijd-en-geslacht (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- May, C.; Montori, V.M.; Mair, F.S. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ 2009, 339, b2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salisbury, C.; Man, M.-S.; Bower, P.; Guthrie, B.; Chaplin, K.; Gaunt, D.M.; Brookes, S.; Fitzpatrick, B.; Gardner, C.; Hollinghurst, S.; et al. Management of multimorbidity using a patient-centred care model: A pragmatic cluster-randomised trial of the 3D approach. Lancet 2018, 392, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, K.; Marengoni, A.; Forjaz, M.J.; Jureviciene, E.; Laatikainen, T.; Mammarella, F.; Muth, C.; Navickas, R.; Prados-Torres, A.; Rijken, M.; et al. Multimorbidity care model: Recommendations from the consensus meeting of the Joint Action on Chronic Diseases and Promoting Healthy Ageing across the Life Cycle (JA-CHRODIS). Health Policy Amst. Neth. 2018, 122, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, C.; van den Akker, M.; Blom, J.W.; Mallen, C.D.; Rochon, J.; Schellevis, F.G.; Becker, A.; Beyer, M.; Gensichen, J.; Kirchner, H.; et al. The Ariadne principles: How to handle multimorbidity in primary care consultations. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onder, G.; Palmer, K.; Navickas, R.; Jurevičienė, E.; Mammarella, F.; Strandzheva, M.; Mannucci, P.; Pecorelli, S.; Marengoni, A. Time to face the challenge of multimorbidity. A European perspective from the joint action on chronic diseases and promoting healthy ageing across the life cycle (JA-CHRODIS). Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 26, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: An approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, E1–E25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE Guideline. Multimorbidity: Clinical Assessment and Management. 2016. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Aarts, S.; Akker, M.v.D.; Bosma, H.; Tan, F.; Verhey, F.; Metsemakers, J.; van Boxtel, M. The effect of multimorbidity on health related functioning: Temporary or persistent? Results from a longitudinal cohort study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 73, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kočo, L.; Weekenstroo, H.H.A.; Lambregts, D.M.J.; Sedelaar, J.P.M.; Prokop, M.; Fütterer, J.J.; Mann, R.M. The Effects of Multidisciplinary Team Meetings on Clinical Practice for Colorectal, Lung, Prostate and Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokwute, M.C.; Preda, V.; Di Ieva, A. Determining Contemporary Barriers to Effective Multidisciplinary Team Meetings in Neurological Surgery: A Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2023, 172, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hembree, W.C.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Gooren, L.; Hannema, S.E.; Meyer, W.J.; Murad, M.H.; Rosenthal, S.M.; Safer, J.D.; Tangpricha, V.; T’sjoen, G.G. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 3869–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollet, Q.; Bouvier, V.; Moutel, G.; Launay, L.; Bignon, A.-L.; Bouhier-Leporrier, K.; Launoy, G.; Lièvre, A. Multidisciplinary team meetings: Are all patients presented and does it impact quality of care and survival—A registry-based study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, Y.L.; Bolle, S.; Fockens, P.; Tytgat, K.M.A.J. The Value of Multidisciplinary Team Meetings for Patients with Gastrointestinal Malignancies: A Systematic Review. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, L.C. Evidence supports the use of multidisciplinary team meetings. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

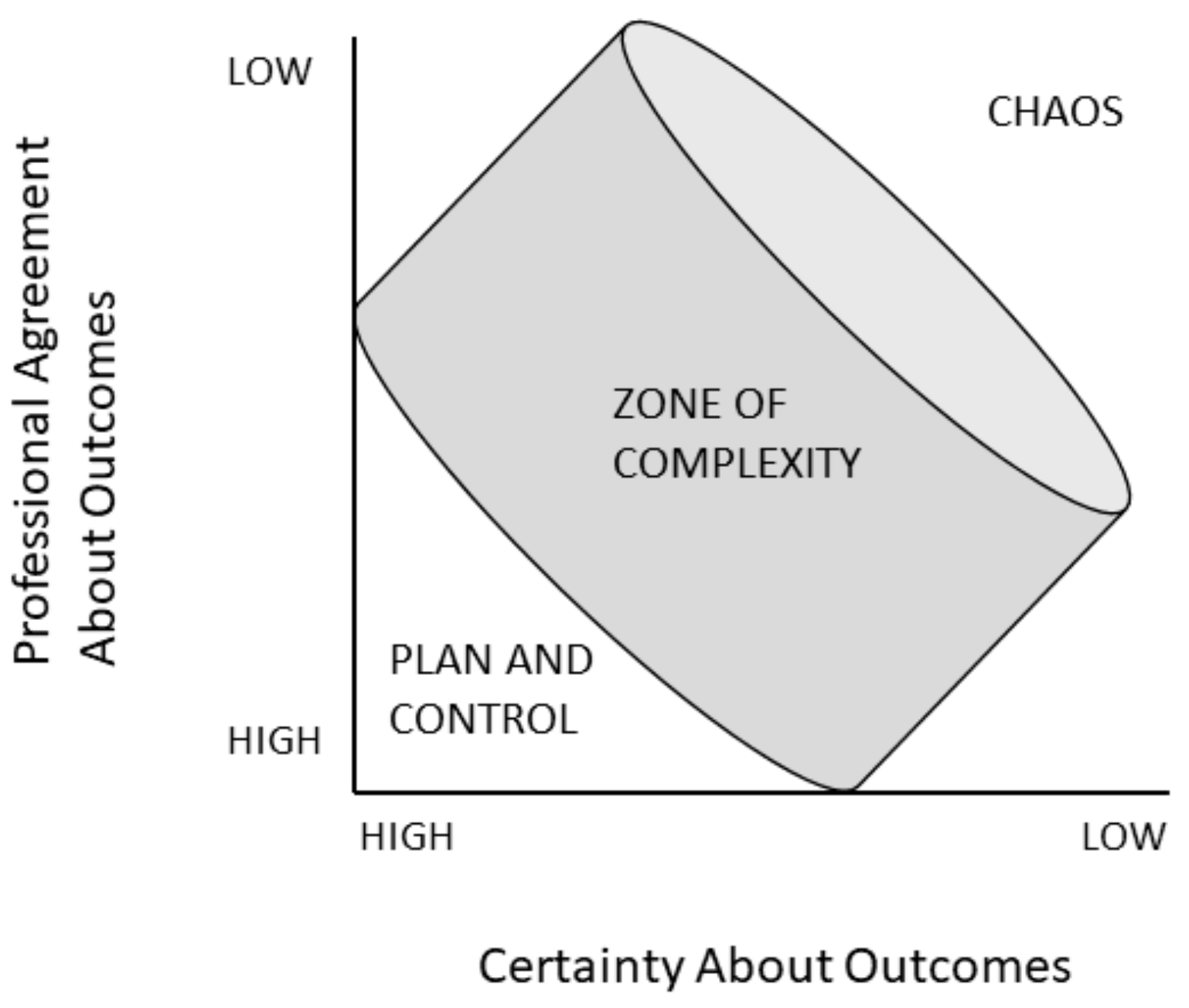

- Waldrop, M.M. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Plsek, P.E.; Greenhalgh, T. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 2001, 323, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.; Holt, T. Complexity and clinical care. BMJ 2001, 323, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pype, P.; Mertens, F.; Helewaut, F.; Krystallidou, D. Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: Understanding team behaviour through team members’ perception of interpersonal interaction. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pype, P.; Krystallidou, D.; Deveugele, M.; Mertens, F.; Rubinelli, S.; Devisch, I. Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: Focus on interpersonal interaction. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 2028–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, R.D. Strategic Management and Organizational Dynamics; Pitmann Publishing: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.S.; Fazio, X.; Kustra, E.; Patrick, L.; Stanley, D. Scoping review of complexity theory in health services research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory. A practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded Theory: Objectivist and Constructivist Methods; Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Grounded+theory%3A+Objectivist+and+constructivist+methods&author=K.+Charmaz&publication_year=2000&pages=509-535 (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Massey, O.T. A proposed model for the analysis and interpretation of focus groups in evaluation research. Eval. Program Plan. 2011, 34, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netwerk Kwalitatief Onderzoek AMC-UVA. Richtlijnen voor Kwaliteitsborging in Gezondheids(zorg)onderzoek: Kwalitatief Onderzoek; AmCOGG: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Letts, L.; Wilkins, S.; Law, M.; Stewart, D.; Bosch, J.; Westmorland, M. Guidelines for Critical Review form: Qualitative Studies. 2007, 12. Available online: http://www.srs-mcmaster.ca/Portals/20/pdf/ebp/qualguideli-nes_version2.0.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedwell, W.L.; Ramsay, P.S.; Salas, E. Helping fluid teams work: A research agenda for effective team adaptation in healthcare. Transl. Behav. Med. 2012, 2, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dukewits, P.; Gowan, L. Creating succesful collaborative teams. J. Staff. Dev. 1996, 17, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa, J.; Bedell, G.; Buchholz, E.S.; Charles, J.; Shigaki, I.S.; Bicchieri, S.M. Team collaboration: A case study of an early intervention team. Qual. Health Res. 2001, 11, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.C.; Hogg, M.A.; Oakes, P.J.; Reicher, S.D.; Wetherell, M.S. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Basil Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Reinders, J.-J.; Krijnen, W. Interprofessional identity and motivation towards interprofessional collaboration. Med. Educ. 2023, 57, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, J.-J.; Versluis, M.; Jaarsma, D. Interprofessionele Identiteit. 2021. Available online: https://demedischspecialist.nl/sites/default/files/2021-12/fms_factsheet_interprofessionele_identiteit_210x297_def.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Brown, E.L.; Poltawski, L.; Pitchforth, E.; Richards, S.H.; Campbell, J.L.; Butterworth, J.E. Shared decision making between older people with multimorbidity and GPs: A qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 2022, 72, e609–e618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

| Discipline | Number of Participants in Focus Groups |

|---|---|

| Internal medicine | 7 |

| Geriatrics | 2 |

| Cardiology | 2 |

| Surgery | 2 |

| Orthopedic surgery | 1 |

| Rehabilitation medicine | 1 |

| Psychiatry | 1 |

| Anesthesiology | 1 |

| Neurology | 1 |

| Psychology | 1 |

| Dentistry | 1 |

| Nursing home elderly care | 1 |

| Gender (male (n); female (n)) | 3 male; 4 female |

| Age in years (mean, range) | 69 (55–80) |

| Number of chronic illnesses (mean, range) | 4 (3–7) |

| Number of health care professionals involved in the outpatient care team (mean, range) | 5 (3–9) |

| Emergency department visits in the past year (median, IQR) | 1 (0–3) |

| Hospitalizations in the past year (median, IQR) | 2 (0–3) |

| Outpatient visits or phone calls in the past year (median, IQR) | 38 (6–57) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gans, E.A.; de Ruijter, U.W.; van der Heide, A.; van der Meijden, S.A.; van den Bos, F.; van Munster, B.C.; de Groot, J.F. A Grounded Theory of Interdisciplinary Communication and Collaboration in the Outpatient Setting of the Hospital for Patients with Multiple Long-Term Conditions. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 533. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14050533

Gans EA, de Ruijter UW, van der Heide A, van der Meijden SA, van den Bos F, van Munster BC, de Groot JF. A Grounded Theory of Interdisciplinary Communication and Collaboration in the Outpatient Setting of the Hospital for Patients with Multiple Long-Term Conditions. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2024; 14(5):533. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14050533

Chicago/Turabian StyleGans, Emma A., Ursula W. de Ruijter, Agnes van der Heide, Suzanne A. van der Meijden, Frederiek van den Bos, Barbara C. van Munster, and Janke F. de Groot. 2024. "A Grounded Theory of Interdisciplinary Communication and Collaboration in the Outpatient Setting of the Hospital for Patients with Multiple Long-Term Conditions" Journal of Personalized Medicine 14, no. 5: 533. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14050533

APA StyleGans, E. A., de Ruijter, U. W., van der Heide, A., van der Meijden, S. A., van den Bos, F., van Munster, B. C., & de Groot, J. F. (2024). A Grounded Theory of Interdisciplinary Communication and Collaboration in the Outpatient Setting of the Hospital for Patients with Multiple Long-Term Conditions. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 14(5), 533. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14050533