1. Introduction

Hypertension is increasingly recognized as an important risk indicator for cognitive decline and impairment in a variety of populations. The connections between hypertension and cognitive function are complex, with data indicating that both the duration and severity of hypertension can impair cognition.

Several studies demonstrate that chronic hypertension causes structural modifications in the brain, possibly contributing to cognitive impairment. For example, hypertension can cause microvascular damage, resulting in lower cerebral blood flow and subsequent cognitive impairment [

1]. Furthermore, hypertension has been linked to abnormalities in brain connections, particularly in memory-critical regions like the hippocampus [

2]. These structural changes can manifest as difficulties in memory, executive function, and overall cognitive performance, even in individuals with a high level of education [

3,

4].

The point in time of hypertension’s beginning appears to be essential. Evidence suggests that midlife hypertension poses a greater risk of cognitive decline in later life than hypertension that develops in older age [

5,

6]. This is particularly crucial because untreated hypertension over decades may lead to cognitive impairment, showing that early detection and therapy are critical [

5]. A systematic analysis revealed that persistent hypertension throughout midlife significantly corresponds with subsequent cognitive impairment, whereas the influence of hypertension in the elderly age is less pronounced [

6]. The evidence strongly supports the notion that hypertension is a modifiable risk factor for cognitive decline, particularly when it occurs in midlife.

Chronic hypertension causes the thickening of the carotid intima and media (IMT) [

7]. Another ultrasound-measurable parameter is flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) in the brachial artery [

8]. Abnormal arterial stiffness can also be diagnosed non-invasively with arteriography [

9]. Several studies have shown that hypertension (and its associated medications) also affects cognitive performance [

10,

11]. In addition to reducing the risk of stroke, treating hypertension can also reduce the risk of cognitive impairment [

12,

13].

However, assessing cognitive functions is time-consuming. A complete, detailed cognitive assessment usually takes 1–1.5 h, including a consultation stage and an evaluation of approximately the same duration. Therefore, it is important to choose the relevant cognitive domain and examine it specifically. Since hypertensive patients make up 25–35% of the population [

14], a marker is needed to select hypertensive patients who are more likely to suffer cognitive impairment. The carotid IMT, arteriography, and FMD are rapid examinations suitable for screening (duration: 6–8 min); therefore, we compared the results of these tests with neuropsychological examinations in our search for the most sensitive screening method, a threshold, and the cognitive domain with the earliest impairment.

2. Materials and Methods

Our research was a single-center, retrospective study that took place in the Department of Neurology, the Clinical Center of the University of Debrecen. This study was performed between January 2016 and December 2019. The study sample was produced in the following manner. We contacted occupational health doctors who regularly see professional firefighters and police officers for necessary annual medical check-ups. Those who had high blood pressure during the examination, as determined by the University of Debrecen Cardiovascular Center. Here, ABPM was used in this case, and they were chosen for the study after considering the exclusion criteria.

Based on the study protocol, we included patients presenting at their primary care provider with newly diagnosed primary hypertension (ICD code: I10). GPs and occupational health physicians aided the patient enrollment process. Asymptomatic and untreated patients whose hypertension was confirmed by ABPM and who had not yet received antihypertensive treatment were included. Primary hypertension was diagnosed following the ESC guidelines, requiring an average blood pressure exceeding 140/90 mmhg based on ABPM results. All subjects were asymptomatic and predominantly middle-aged (active age), identified by screening. Following the ABPM, a CT scan was also performed to detect asymptomatic abnormalities (e.g., silent infarction).

The exclusion criteria included previous stroke, TIA, poor general condition, a life expectancy of <5 years, and comorbidities that significantly influenced this study: diabetes, severe heart disease, arrhythmia, renal failure, tumors, significant carotid artery stenosis, autoimmune disease, psychiatric disorders, dementia, etc. A “silent” infarction or other organic abnormalities detected in cranial CT also resulted in exclusion. Additional exclusion criteria included pregnancy, postpartum period, alcohol dependence, and extreme obesity, which was defined as a body mass index (BMI) of greater than 35 kg/m

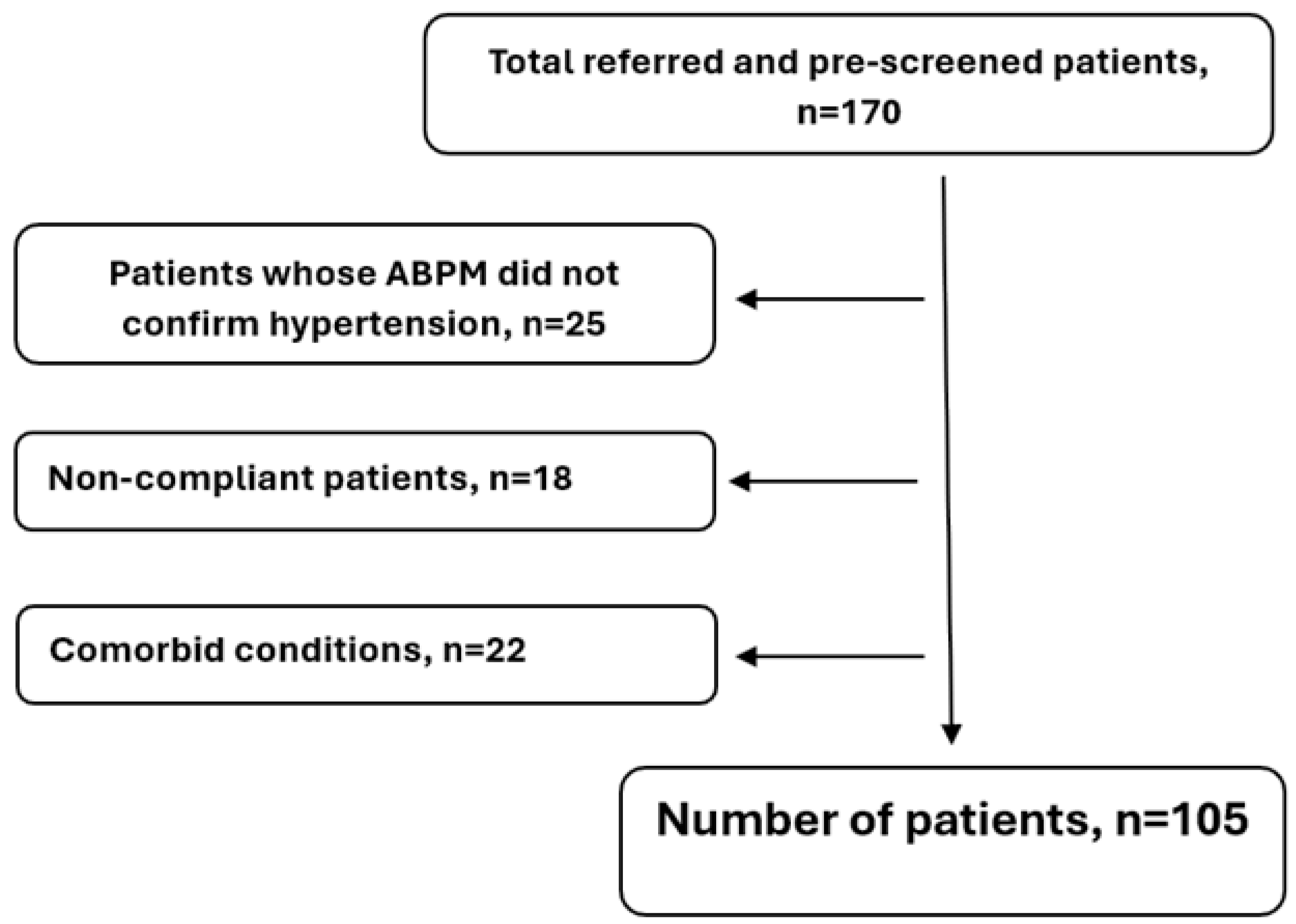

2, as this level is associated with significant comorbidities and health risks. The exclusion process is presented in

Figure 1.

2.1. Methods

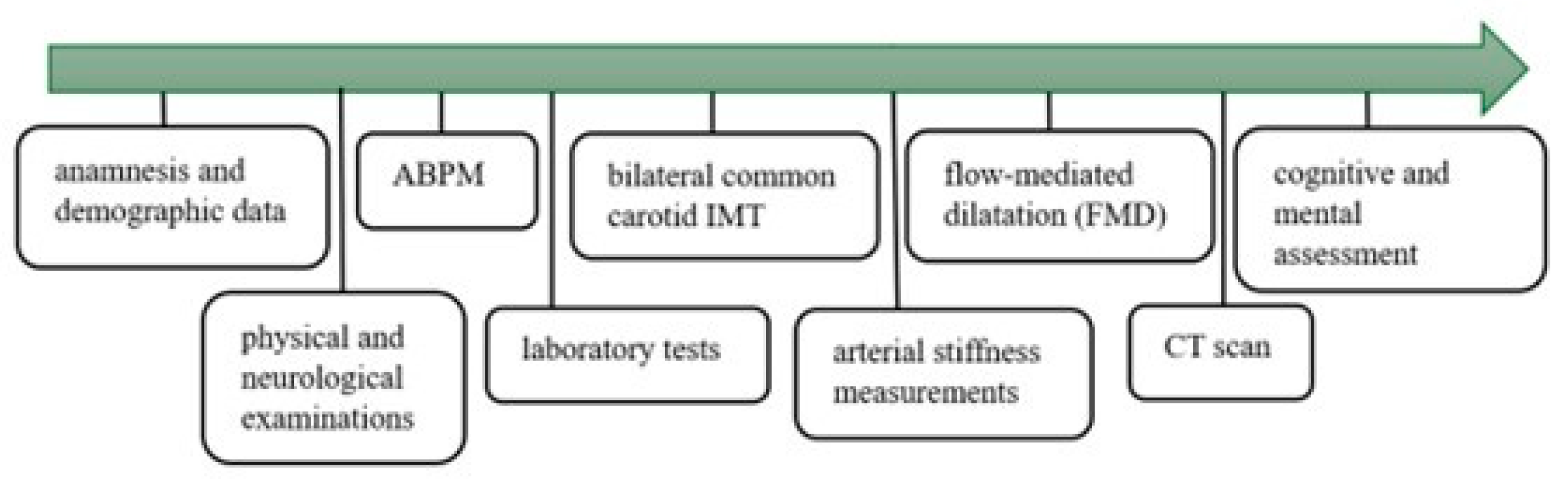

The available data covered detailed medical history, demographic variables, the results of physical and neurological examinations, cognitive and mental assessment, and laboratory tests, including serum electrolytes, renal function, glucose, lipid profiles, complete blood count, CRP, hemoglobin A1C, fibrinogen levels, and urinalysis. The study protocol is summarized in

Figure 2.

These assessments were followed by 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). Blood pressure was measured every 15 min during the day (from 6:00 to 22:00) and every 30 min at night (from 22:00 to 6:00). Based on the ABPM data, an internal medicine specialist evaluated the results, determined daytime and nighttime mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and the systolic and diastolic hyperbaric index. For the ABPM measurements, Cardiospy ABPM equipment from Labtech Ltd. (Debrecen, Hungary, model: EC-ABP) was used.

The bilateral common carotid IMT was measured with a 7.5 MHz linear probe (Philips HD 11 XE from Unicorp Biotech Kft., Budapest, Hungary). The IMT was measured on the far wall of the common carotid artery [

15].

Flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) measurement of the brachial artery was performed using an HP Sonos 5500 ultrasound device with a 10 MHz linear test transducer (from National Utrasound, Tampa, FL, USA). The FMD was expressed as the percentage increase in the resting diameter of the artery after cuff release (the forearm cuff was inflated to suprasystolic pressure for 5 min, 10–40 mmHg above the patient’s systolic pressure [

16]. The brachial artery FMD is a marker of endothelial damage in large arteries [

17].

Arterial stiffness measurements were performed using a TensioClinic arteriograph (TensioMed Ltd., Budapest, Hungary). Arterial stiffness was assessed by determining the augmentation index (AIx) and pulse wave velocity (PWV) [

18]; the latter measures the rate of pulse wave propagation between the carotid and femoral arteries, which mainly reflects the thickening of the tunica media [

19]. Abnormal stiffness and FMD values reflect the likelihood of future vascular injury, and their values are interrelated [

20].

2.2. Neuropsychological Evaluation

All patients underwent a detailed 90 min long neuropsychological evaluation with the guidance of a psychologist. The test was designed to determine the main neurocognitive functions listed in the 5th Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5): reaction time, attention, executive function, learning, memory, and perceptual-motor skills. The test package included the most sensitive tests to reveal minor differences in cognitive function that are not necessarily detectable during everyday activities. For the statistical analysis, all variables were standardized, inverse scales were reversed, and all were summed as total.

The order of tasks was different from subject to subject to control for the effect of the task order on performance (e.g., due to fatigue). Two key aspects were considered when the sequence of tasks was created. Exercises requiring creativity (e.g., the five-point test and verbal fluency tests) were performed prior to those measuring intelligence. During the 20 min delay of the delayed recognition task, only nonverbal tasks were performed to avoid interference. Before the baseline assessment, we drew randomly from these tests. All neurocognitive functions were measured, especially the most sensitive ones to hypertension, which are attention, executive functions, and memory. The assessed cognitive domains and the validated tests used are shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Statistical Methods

The main characteristics of the patients were described with means ± SD in the case of continuous variables, and proportions were calculated for categorical variables. The chi-squared test was used to assess the relationship between the categorical variables. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality. Because of the non-normal distribution of the variables, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated. Spearman’s correlation was used to estimate the extent of correlations between continuous variables. Correlation coefficients were interpreted based on Akoglu’s work [

39]. A composite measure (cognitive index) was created, which summarized the achievements of a person. Some indicators were reversed, and others were standardized to eliminate the differences in dimensions and to have a straight tendency. The cut-off value for the FMD/IMT ratio was found by cyclic linear regression models based on possible integer values, and we performed ROC analysis. Multiple linear regression models were created to evaluate the associations, which were found in simple analyses, and to adjust for potential confounders. Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Excel, 2016) and the Intercooled Stata v13.0 software were used for the data analysis. To interpret the Spearman’s correlation coefficient, cut-off points generally accepted in medicine were used [

39].

3. Results

A total of 105 subjects were enrolled in this study (

Table 2), with a mean (±standard deviation) age of 45.08 ± 11.42 years and a male-to-female ratio of 2.09. The systolic and diastolic mean ABPM results (± standard deviation) were 144.37 ± 10.96 and 87.14 ± 7.58 mmHg.

The descriptive statistics of the blood test results and the ABPM, IMT, FMD, AIX, and PWV parameters are in the

Appendix A and

Appendix B. The descriptive statistics of the cognitive test results are in

Table 3.

To combine the effects of the most important variables, a composite index was derived as the ratio between the FMD value and the mean of the left and right carotid IMT values. This indicator was created to neutralize the effect of between-patient differences in physique: a carotid of greater diameter is inherently paired with a greater IMT; thus, the differences between thinner and thicker vessels are eliminated.

In the first step, the cognitive domains correlated with the FMD were identified.

The FMD showed a fair (rho = 0.39) positive significant (

p = 0.007) correlation with working memory, a poor (rho = 0.29) positive significant (

p = 0.016) correlation with complex attention, a fair (rho = 0.34) positive significant (

p = 0.005) correlation with learning abilities, and a fair (rho = 0.39) positive significant (

p = 0.014) correlation with executive functions. These results are presented in

Table 4. It can be concluded that with decreasing FMD values, performance in working memory, attention, learning abilities, and executive functions also deteriorates.

In the second stage, the cognitive domains related to the IMT were found.

The IMT showed a fair (rho = −0.49) negative significant (

p < 0.001) correlation with complex attention and a fair (rho = −0.42) negative significant (

p < 0.001) correlation with reaction time. These results are presented in

Table 4. Thus, as the IMT values increase, reaction time decreases, attention deteriorates, and the efficiency of executive functions worsens.

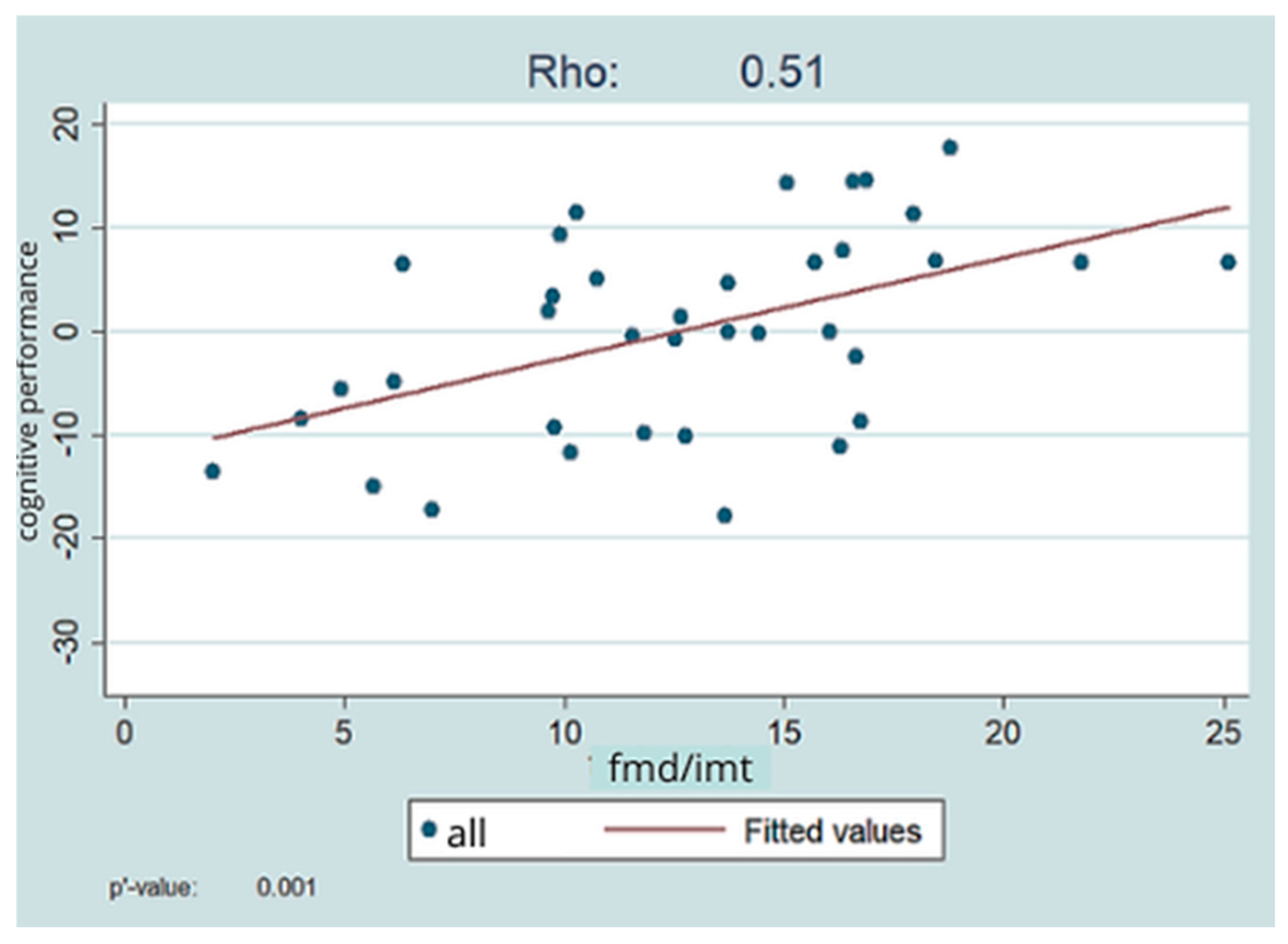

Next, we examined the relationship between the derived FMD/IMT ratio and the overall index generated from the results of cognitive function assessments.

The composite FMD/IMT value showed a fair (rho = 0.51) positive significant (

p = 0.001) relationship with the overall index of cognitive functions, i.e., better FMD and IMT values were associated with better cognitive performance. This is shown in

Figure 3.

Examining the relationship between the FMD/IMT ratio and the overall cognitive index, we looked at which FMD/IMT value can be used as a cut-off for cognitive impairment. Based on our results, an FMD/IMT ratio of 15 represents a cut-off value (p = 0.002; R-squared = 0.23).

This indicates that below a cut-off value of 15 FMD/IMT, it is worth initiating a detailed cognitive assessment, and below FMD and IMT values of 6.44 and 0.43, respectively, deterioration of working memory, complex attention, reaction time, learning, and executive functions are expected.

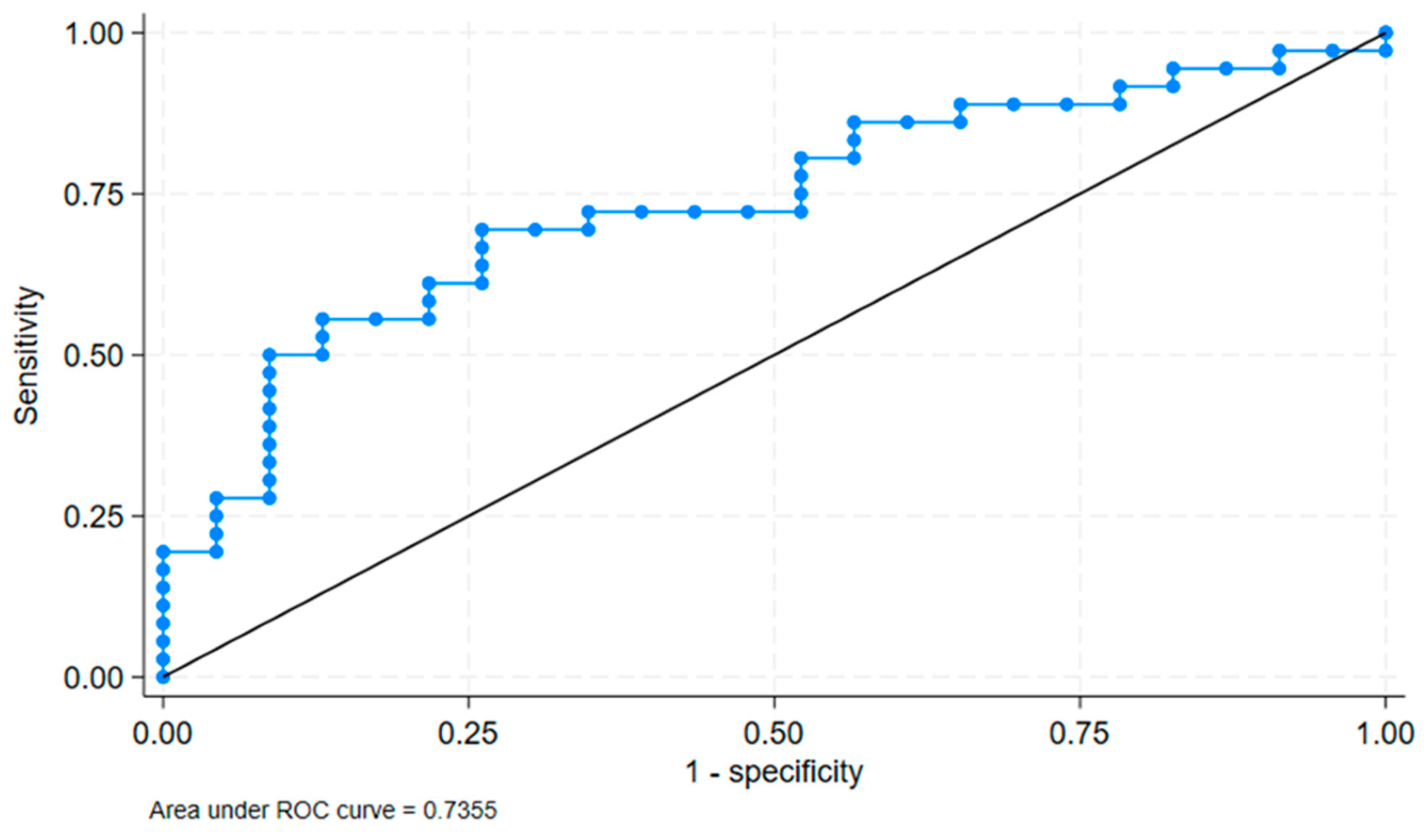

We verified the cut-off value with ROC analysis. The ROC analysis showed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.7355 with a standard error of 0.0658 and a 95% confidence interval of [0.60655, 0.86446]. This is shows in

Figure 4. This indicates a good discriminatory ability of the FMD/IMT binary variable at a cut-off of 14.47 to distinguish between the presence and absence of cognitive impairment.

AIx and PWV measured by arteriography did not show significant correlations with the overall index of cognitive function. As for the PWV, a significant (

p = 0.010) fair (rho = −0.31) negative correlation was seen with working memory and a significant (

p = 0.012) poor (rho = −0.27) negative correlation with complex attention. In the case of AIx, a fair negative (rho = −0.36) significant (

p < 0.001) relationship was detected with reaction time and a significant (

p = 0.020) fair (rho = −0.30) negative relationship with executive functions. The significant findings are presented in

Table 5.

We performed a regression analysis with covariatee adjustment, and in the case of FMD/IMT, the significant positive association remained (0.2314 [0.0198–0.443]) after adjusting for age group and gender. The findings are presented in

Table 6.

4. Discussion

The most important new observation of our study is that by combining the results of two rapid tests (IMT and FMD), we obtained a cut-off value that helps in the selection of hypertensive individuals for whom time-consuming, complex cognitive tests are expected to produce abnormal results. In patients with FMD/IMT ratios lower than a cut-off of 15, we will most likely find cognitive differences. These are expected in the domains of reaction time, attention, executive functions, and working memory.

Hypertension is a chronic disease that causes multiorgan damage (arteries, heart, kidney, and central nervous system) over time [

40]. Untreated hypertension also impairs cognition [

41]. As hypertension simultaneously damages large blood vessels (e.g., carotid and brachial), there has been a need in the past for easily and rapidly detectable vascular markers (IMT, FMD, and stiffness) that serve as biomarkers to screen individuals at increased risk for vascular events. Flow-mediated dilatation (FMD), carotid intima–media thickness (IMT), and arterial stiffness (pulse wave velocity (PWV) and augmentation index (AIX)) are sensitive, non-invasive parameters used to measure the severity of endothelial function and vascular wall damage [

42]. Previous studies have described that carotid intima–media thickening and arterial stiffness are markers of arteriosclerosis [

43,

44]. The results of a 2020 study confirmed the association between intima–media thickness and cognitive decline and the notion that an increase in intima–media thickness predicts the subsequent development of cognitive decline was also supported. Memory functions and attention were the most commonly affected domains [

45]. Csipo and colleagues demonstrated by FMD and stiffness studies that poorer FMD and stiffness levels are associated with poorer cognitive performance in the elderly [

46]. Others have observed an association between stiffness and memory impairment in men. Based on their results, increased arterial stiffness was significantly and independently associated with memory impairment in the men they studied [

47].

A detailed review of the association between stiffness and cognitive function was also published; it found an association between pathological stiffness and cognitive decline [

48]. In our own study, we found no significant association between cognitive differences and stiffness, which may be explained by the fact that our study population consisted of relatively young individuals (mid-40s) whose hypertension had presumably persisted for a short time. In their study, Kearney-Schwartz et al. observed a significant positive correlation between memory scores and PWV in males [

47]. The results of our own study did not support between-gender differences; however, in the above-mentioned study, the mean age was more than 20 years older than in our own study group, and patients with chronic hypertension were studied, while our research involved newly diagnosed patients. In a study of patients with minor neurocognitive impairment, Tonacci et al. found decreased FMD values [

49]. Tachibana et al. also measured decreased levels of FMD in vascular dementia patients compared with healthy controls. This study considered FMD to be a more sensitive marker than IMT [

50]. A report on 10 studies processing data from 2791 patients found that impairment of FMD is associated with poorer neuropsychological performance, particularly in executive functions and working memory tasks [

51]. In hypertensive patients studied by Saka et al., FMD was significantly decreased and inversely correlated with intima–media thickness as well as diastolic blood pressure. They suggested that carotid IMT is a possible indicator of abnormal endothelial function based on a positive correlation with hypertension and a significant negative correlation with FMD [

52]. According to Smith et al., impaired FMD is associated with poorer neurocognitive function in overweight, hypertensive patients [

53]. Del Brutto et al. highlight the role of age in the analysis of the relationship between IMT and cognitive functions [

45]. Our own study did not yield similar results in terms of age, but we emphasize that we studied relatively young, asymptomatic, newly diagnosed patients, whereas in Del Gross’s study, the mean age was more than 10 years older. In a 2016 review, Naiberg et al. [

51] summarized the results of studies examining the relationship between FMD and neurocognition. They concluded that studies to date suggest impaired FMD being most strongly associated with attention, executive function, and working memory tasks. Our own study also showed a significant correlation with impaired levels of FMD in relation to learning, which is a novel finding in the literature.

Another main goal of our study was to determine which cognitive domains are primarily impaired in early hypertension. With this, our goal was to find a select group of sensitive tests that are likely to be abnormal to be used instead of time-consuming detailed cognitive tests. To our knowledge, there has never been a study that has examined the relationships between cognitive function and the parameters presented above for a similar purpose. In their 2009 study, Kearney-Schwartz et al. [

47] found significant memory impairment in hypertensive patients. We did not detect memory impairment but found impaired complex attention, response time, working memory, and executive functions. The reason for the difference between these findings may have been the younger age of our patients, as Kearney-Schwartz studied older patients who were already expected to have memory impairment. The results of Naiberg et al., in turn, confirm our observations, as they also found early impairment of attention, executive functions, and working memory [

51]. Deterioration of executive functions and psychomotor speed was also observed by Smith et al. [

53].

This study had several limitations that should be acknowledged. This work identified a composite vascular marker (FMD/IMT ratio) to screen for cognitive impairment in young hypertension patients, providing a useful tool for early management. The single-center study methodology and limited sample size may restrict the generalizability of the findings. To confirm the findings, more research, including older and more varied groups, is required. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design precludes the evaluation of cognitive and vascular changes over time and prevents causal inferences. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish causal relationships and the temporal progression of cognitive decline in hypertension. Excluding persons with concomitant illnesses like diabetes and obesity may not accurately represent the hypertensive population. Future research should include patients with these comorbidities to determine the generalizability of our findings. Future research should also aim for a larger, more diverse population, with long follow-ups to validate the findings and assess the impact of pressure-reducing therapy on cognitive outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In our study, we investigated the relationships between physiological parameters associated with hypertension and cognitive function in newly diagnosed, young, primary hypertensive patients.

For the FMD/IMT ratio, a cut-off value was determined to identify patients for whom early cognitive function assessment is of paramount importance. In addition, we confirmed an association between increased intima–media thickness and lesser performance in complex attention and response time and between reduced flow-mediated dilatation and poorer attention, learning, working memory, and executive functions.

Based on our results, IMT and FMD levels and their composite ratio are suitable for the identification of particularly vulnerable patients who require detailed cognitive examination for the early detection and treatment of functional disorders. Although significant, the moderate correlation coefficients indicate that FMD and IMT are part of a multifactorial framework affecting cognitive function. Future research should investigate additional factors to improve the accuracy of risk stratification.

In early hypertension, assessment is required of the cognitive domains of attention, executive functions, working memory, and reaction time. The examination and monitoring of performance in these cognitive domains is important in hypertensive individuals who rely on such performance in their daily work.

Our findings demonstrate that the FMD/IMT ratio is a useful and sensitive predictor of early cognitive impairment in young hypertension patients. However, additional multicenter research with larger populations and longer follow-ups would be helpful to verify these findings. Future studies will investigate whether early interventions, such as cognitive training, lifestyle changes, and improved hypertension management based on FMD and IMT values, can mitigate cognitive decline, thereby justifying their use as routine markers in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

R.M.: data curation, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. A.N.: data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. E.C.: data curation, investigation, and writing—review and editing. M.A.: methodology. Á.D.: investigation. A.T.: validation, visualization, and writing—review and editing. L.C.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Gedeon Richter research grant (4700168520 KK/186/2016) and the National Research, Development, and Innovation Fund (K120042).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Debrecen, and this study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (registration number: 4700168520; file number: KK/186/2016; date: 15 January 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

After receiving oral and written information, all participants gave written consent to participate in this research.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to containing health and medical information that could compromise the privacy of the research participants.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the support and help from Pál Soltész and László Kardos. We are grateful to László Oláh, Neurology Clinic of University of Debrecen, for his contributions to the study’s implementation and continuous support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of blood test results.

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of blood test results.

| Variable | n | Mean ± SD | Median [IQR] | Interval |

|---|

| Na mmol/L | 85 | 140.41 ± 2.18 | 141 [139–142] | 133–146 |

| K mmol/L | 85 | 4.27 ± 0.31 | 4.2 [4.1–4.5] | 3.5–5.3 |

| Cl mmol/L | 83 | 104.08 ± 2.22 | 104 [103–106] | 99–111 |

| Glucose mmol/L | 87 | 5.3 ± 1.15 | 5 [4.7–5.6] | 3.6–6.0 |

| Urea mmol/L | 86 | 4.99 ± 1.27 | 4.9 [4.1–5.8] | 2.8–8.0 |

| Creatinine imol/L | 87 | 76.34 ± 15.68 | 75 [66–88] | 44–84 |

| GOT U/L | 85 | 23.71 ± 9.54 | 21 [18–26] | <40 |

| GGT U/L | 87 | 43.34 ± 60.02 | 28 [19–43] | 7–50 |

| Fibrinogen g/L | 81 | 3.17 ± 0.96 | 3.08 [2.49–3.48] | 1.5–4 |

| TGs mmol/L | 87 | 1.81 ± 2.2 | 1.3 [0.8–1.9] | <1.7 |

| Chol mmol/L | 87 | 5.16 ± 1 | 5 [4.6–5.6] | 2.0–5.2 |

| HDL-C mmol/L | 84 | 1.3 ± 0.38 | 1.29 [1–1.5] | >1.3 |

| LDL-C mmol/L | 83 | 3.33 ± 0.79 | 3.2 [2.89–3.7] | 1.0–3.4 |

| HgbA1c mmol/mol | 67 | 5.35 ± 0.66 | 5.3 [5–5.6] | 4.2–6.1 |

| ESR mm/h | 82 | 11.51 ± 7.31 | 12 [6–16] | 0–15 |

| WBC G/L | 88 | 6.63 ± 1.62 | 6.58 [5.63–7.26] | 4.5–10.8 |

| RBC T/L | 88 | 4.93 ± 0.4 | 4.92 [4.67–5.17] | 4.2–5.4 |

| Hgb g/L | 88 | 145.9 ± 13.09 | 146 [139–154.5] | 115–150 |

| Htc | 88 | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.43 [0.41–0.45] | 0.35–0.47 |

| CRP mg/L | 32 | 4.77 ± 5.69 | 2.35 [1.3–6.2] | <4.6 |

| Thr G/L | 86 | 240.77 ± 60.21 | 221 [205–275] | 150–400 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics of ABPM, IMT, FMD, AIX, and PWV parameters.

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics of ABPM, IMT, FMD, AIX, and PWV parameters.

| Variable | n | Mean ± SD | Median [IQR] |

|---|

| left_carotid_imt_lcca | 92 | 0.59 ± 0.12 | 0.58 [0.51–0.66] |

| right_carotid_imt_rcca | 92 | 0.57 ± 0.11 | 0.54 [0.49–0.61] |

| carotid_mean_imt_rcca_lcca | 82 | 0.58 ± 0.11 | 0.56 [0.5–0.62] |

| fmd_dilation | 66 | 7.67 ± 3.04 | 7.54 [5.75–9.2] |

| fmd/imt | 58 | 14.32 ± 6.71 | 13.78 [9.79–17.31] |

| arteriograph_aix | 93 | –15.78 ± 33.08 | −16.2 [−43.9–10.4] |

| arteriograph_pwv | 93 | 9.99 ± 2.29 | 9.7 [8.6–11.1] |

| abpm_active_sbp | 92 | 147.87 ± 11.11 | 147 [141.5–152] |

| abpm_active_dbp | 92 | 88.76 ± 11.25 | 89 [84–93.5] |

| abpm_active_shi | 90 | 384.08 ± 174.76 | 355 [266–439] |

| abpm_active_dhi | 90 | 221.39 ± 98.26 | 212 [158–265] |

| abpm_active_pp | 92 | 57.93 ± 7.81 | 58 [51.5–63] |

| abpm_passive_sbp | 90 | 129.88 ± 18.2 | 129 [121–140] |

| abpm_passive_dbp | 90 | 77.74 ± 8.99 | 76 [71–84] |

| abpm_passive_shi | 88 | 392.9 ± 250.75 | 328 [226.5–529.5] |

| abpm_passive_dhi | 88 | 193.09 ± 155.82 | 164 [86–262.5] |

| abpm_passive_pp | 90 | 52.89 ± 9.36 | 51.5 [47–58] |

| abpm_mean_sbp | 93 | 144.37 ± 10.96 | 143 [139–150] |

| abpm_mean_dbp | 93 | 87.14 ± 7.58 | 86 [82–91] |

| abpm_mean_shi | 90 | 391.78 ± 179.08 | 365 [275–451] |

| abpm_mean_dhi | 90 | 226.32 ± 93.56 | 215.5 [161–272] |

| abpm_mean_pp | 92 | 56.87 ± 7.84 | 57 [50–62] |

| abpm_mean_map | 48 | 198.29 ± 114.39 | 163 [107.5–248] |

References

- Gąsecki, D.; Kwarciany, M.; Nyka, W.; Narkiewicz, K. Hypertension, brain damage and cognitive decline. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2013, 15, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, R.; Rolls, E.; Cheng, W.; Feng, J. Hypertension is associated with reduced hippocampal connectivity and impaired memory. eBiomedicine 2020, 61, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anto, E.; Siagian, L.; Siahaan, J.; Silitonga, H.; Nugraha, S. The relationship between hypertension and cognitive function impairment in the elderly. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 1440–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muela, H.; Costa-Hong, V.; Yassuda, M.; Moraes, N.; Memória, C.; Macedo, T.; Machado, M.F.; Bor-Seng-Shu, E.; Massaro, A.R.; Nitrini, R.; et al. Impact of hypertension on cognitive performance in individuals with high level of education. Brain Nerves 2017, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, O. Midlife hypertension is a risk factor for some, but not all, domains of cognitive decline in later life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 2023, 42, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farron, M.; Kabeto, M.; Dey, A.; Banerjee, J.; Levine, D.; Langa, K. Hypertension and cognitive health among older adults in India. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68 (Suppl. S3), S29–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Neto, P.J.; Sena-Santos, E.H.; Meireles, D.P.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Santos, I.S.; Bensenor, I.M.; Lotufo, P.A. Association of Carotid Plaques and Common Carotid Intima-media Thickness with Modifiable Cardiovascular Risk Factors. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2021, 30, 105671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, S.M.; Bruno, R.M.; Shkredova, D.A.; Dawson, E.A.; Jones, H.; Hopkins, N.D.; Hopman, M.; Bailey, T.G.; Coombes, J.S.; Askew, C.D.; et al. Reference Intervals for Brachial Artery Flow-Mediated Dilation and the Relation with Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Hypertension 2021, 77, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutouyrie, P.; Chowienczyk, P.; Humphrey, J.D.; Mitchell, G.F. Arterial Stiffness and Cardiovascular Risk in Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C.; Yaffe, K.; Biller, J.; Bratzke, L.C.; Faraci, F.M.; Gorelick, P.B.; Gulati, M.; Kamel, H.; Knopman, D.S.; Launer, L.J.; et al. Impact of Hypertension on Cognitive Function: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2016, 68, e67–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhec, M.; Keuschler, J.; Serra-Mestres, J.; Isetta, M. Effects of different antihypertensive medication groups on cognitive function in older patients: A systematic review. Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2017, 46, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Brok, M.; van Dalen, J.W.; Abdulrahman, H.; Larson, E.B.; van Middelaar, T.; van Gool, W.A.; van Charante, E.; Richard, E. Antihypertensive Medication Classes and the Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1386–1395.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, N.; Mohan, D.; Fuad, S.; Basavanagowda, D.M.; Alrashid, Z.A.; Kaur, A.; Rathod, B.; Nosher, S.; Heindl, S.E. The Association Between Hypertension and Cognitive Impairment, and the Role of Antihypertensive Medications: A Literature Review. Cureus 2020, 12, e12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.T.; Bundy, J.D.; Kelly, T.N.; Reed, J.E.; Kearney, P.M.; Reynolds, K.; Chen, J.; He, J. Global Disparities of Hypertension Prevalence and Control: A Systematic Analysis of Population-Based Studies From 90 Countries. Circulation 2016, 134, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojima, S.; Kubozono, T.; Kawasoe, S.; Kawabata, T.; Miyahara, H.; Tokushige, K.; Ohishi, M. Gender differences in the risk factors associated with atherosclerosis by carotid intima-media thickness, plaque score, and pulse wave velocity. Heart Vessel. 2021, 36, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiba, L. Endothelial function testing. In Manual of Neurosonology; Csiba, L., Baracchini, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, D.H.; Black, M.A.; Pyke, K.E.; Padilla, J.; Atkinson, G.; Harris, R.A.; Parker, B.; Widlansky, M.E.; Tschakovsky, M.E.; Green, D.J. Assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans: A methodological and physiological guideline. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H2–H12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Pinto, D.; Rodrigues-Machado, M. Applications of arterial stiffness markers in peripheral arterial disease. J. Vasc. Bras. 2019, 18, e20180093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omboni, S.; Posokhov, I.N.; Rogoza, A.N. Relationships between 24-h blood pressure variability and 24-h central arterial pressure, pulse wave velocity and augmentation index in hypertensive patients. Hypertens. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hypertens. 2017, 40, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEniery, C.M.; Wallace, S.; Mackenzie, I.S.; McDonnell, B.; Yasmin; Newby, D.E.; Cockcroft, J.R.; Wilkinson, I.B. Endothelial function is associated with pulse pressure, pulse wave velocity, and augmentation index in healthy humans. Hypertension 2006, 48, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV); Database record; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, M.; Szegedi, M. Az Intelligencia Mérése; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Toulouse, E.; Pieron, H. Test of Perception and Attention; TEA Ediciones, SA: Madrid, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Czigler, I. A Figyelem Pszichológiája; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, C.J. Stroop Color and Word Test: A Manual for Clinical and Experimental Uses; Stoelting Company: Wood Dale, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Tárnok, Z.; Bognár, E.; Farkas, L.; Aczél, B.; Gádoros, J. A végrehajtó funkciók vizsgálata Tourette-szindrómában és figyelemhiányos-hiperaktvitás-zavarban. In A Fejlődés Zavarai és Vizsgálómódszerei; Racsmány, M., Ed.; Akadémiai kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reitan, R.M. The relation of the Trail Making Test to organic brain damage. J. Consult. Psychol. 1955, 19, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, S.; Fischer, R.; Ferstl, R.; Mehdorn, H.M. Normative data and psychometric properties for qualitative and quantitative scoring criteria of the Five-point Test. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2009, 23, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucha, L.; Aschenbrenner, S.; Koerts, J.; Lange, K.W. The five-point test: Reliability, validity and normative data for children and adults. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csépe, V.; Győri, M.; Ragó, A. Általános Pszichológia 1–3.–2. Tanulás–Emlékezés–Tudás; Osiris Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. Experiments on “prehension”. Mind 1887, 12, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racsmány, M.; Lukács, Á.; Németh, D.; Pléh, C. A verbális munkamemória magyar nyelvű vizsgálóeljárásai. Magy. Pszichológiai Szle. 2005, 60, 479–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, P. Memory and the Medial Temporal Region of the Brain. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QB, Canada, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, A. L’examen Clinique en Psychologie; Presses Universitaries De France location: Paris, France, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama, C.L.; D’Elia, L.F.; Dellinger, A.M.; Becker, J.T.; Selnes, O.A.; Wesch, J.E.; Chen, B.B.; Satz, P.; van Gorp, W.; Miller, E.N. Alternate forms of the Auditory-Verbal Learning Test: Issues of test comparability, longitudinal reliability, and moderating demographic variables. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. Off. J. Natl. Acad. Neuropsychol. 1995, 10, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kónya, A.; Verseghi, A.; Rey, T. Rey: Emlékezeti Vizsgálatok; Pszicho-Teszt: Budapest, Hungary, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak, M.D. Neuropsychological Assessment, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tánczos, T.; Janacsek, K.; Németh, D. A verbális fluencia-tesztek I.-II. Psychiatr. Hung. 2014, 29, 158–207. [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Díaz, Z.M.; Peña-Sánchez, M.; González-Quevedo Monteagudo, A.; González-García, S.; Arias-Cadena, P.A.; Brown-Martínez, M.; Betancourt-Loza, M.; Cordero-Eiriz, A. Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Associated with Subclinical Vascular Damage Indicators in Asymptomatic Hypertensive Patients. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopman, D.; Boland, L.L.; Mosley, T.; Howard, G.; Liao, D.; Szklo, M.; McGovern, P.; Folsom, A.R.; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. Neurology 2001, 56, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabiyik, U.; Savas, G.; Yasan, M.; Murat Bucak, H.; Cesur, B.; Cetinkaya, Z.; Topsakal, R.; Dogan, A. Evaluation of the relationship between pseudo-hypertension and the parameters of subclinical atherosclerosis. Blood Press. Monit. 2021, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, P.B.; Scuteri, A.; Black, S.E.; Decarli, C.; Greenberg, S.M.; Iadecola, C.; Launer, L.J.; Laurent, S.; Lopez, O.L.; Nyenhuis, D.; et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke 2011, 42, 2672–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikai, E.; Andrejkovics, M.; Balajthy-Hidegh, B.; Hofgárt, G.; Kardos, L.; Diószegi, Á.; Rostás, R.; Czuriga-Kovács, K.R.; Csongrádi, É.; Csiba, L. Influence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on reversibility of alterations in arterial wall and cognitive performance associated with early hypertension: A follow-up study. Medicine 2019, 98, e16966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Brutto, O.H.; Mera, R.M.; Recalde, B.Y.; Del Brutto, V.J. Carotid Intima-media Thickness, Cognitive Performance and Cognitive Decline in Stroke-free Middle-aged and Older Adults. The Atahualpa Project. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2020, 29, 104576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csipo, T.; Lipecz, A.; Fulop, G.A.; Hand, R.A.; Ngo, B.N.; Dzialendzik, M.; Tarantini, S.; Balasubramanian, P.; Kiss, T.; Yabluchanska, V.; et al. Age-related decline in peripheral vascular health predicts cognitive impairment. GeroScience 2019, 41, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney-Schwartz, A.; Rossignol, P.; Bracard, S.; Felblinger, J.; Fay, R.; Boivin, J.M.; Lecompte, T.; Lacolley, P.; Benetos, A.; Zannad, F. Vascular structure and function is correlated to cognitive performance and white matter hyperintensities in older hypertensive patients with subjective memory complaints. Stroke 2009, 40, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lyu, P.; Ren, Y.; An, J.; Dong, Y. Arterial stiffness and cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 380, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonacci, A.; Bruno, R.M.; Ghiadoni, L.; Pratali, L.; Berardi, N.; Tognoni, G.; Cintoli, S.; Volpi, L.; Bonuccelli, U.; Sicari, R.; et al. Olfactory evaluation in Mild Cognitive Impairment: Correlation with neurocognitive performance and endothelial function. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2017, 45, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, H.; Washida, K.; Kowa, H.; Kanda, F.; Toda, T. Vascular Function in Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Dementia. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2016, 31, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiberg, M.R.; Newton, D.F.; Goldstein, B.I. Flow-Mediated Dilation and Neurocognition: Systematic Review and Future Directions. Psychosom. Med. 2016, 78, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, B.; Oflaz, H.; Erten, N.; Bahat, G.; Dursun, M.; Pamukcu, B.; Mercanoglu, F.; Meric, M.; Karan, M.A. Non-invasive evaluation of endothelial function in hypertensive elderly patients. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2005, 40, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.J.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Babyak, M.A.; Hinderliter, A.; Sherwood, A. Association of vascular health and neurocognitive performance in overweight adults with high blood pressure. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2011, 33, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).