Patient Experiences and Clinical Outcomes in a Multidisciplinary Perioperative Transitional Pain Service

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting

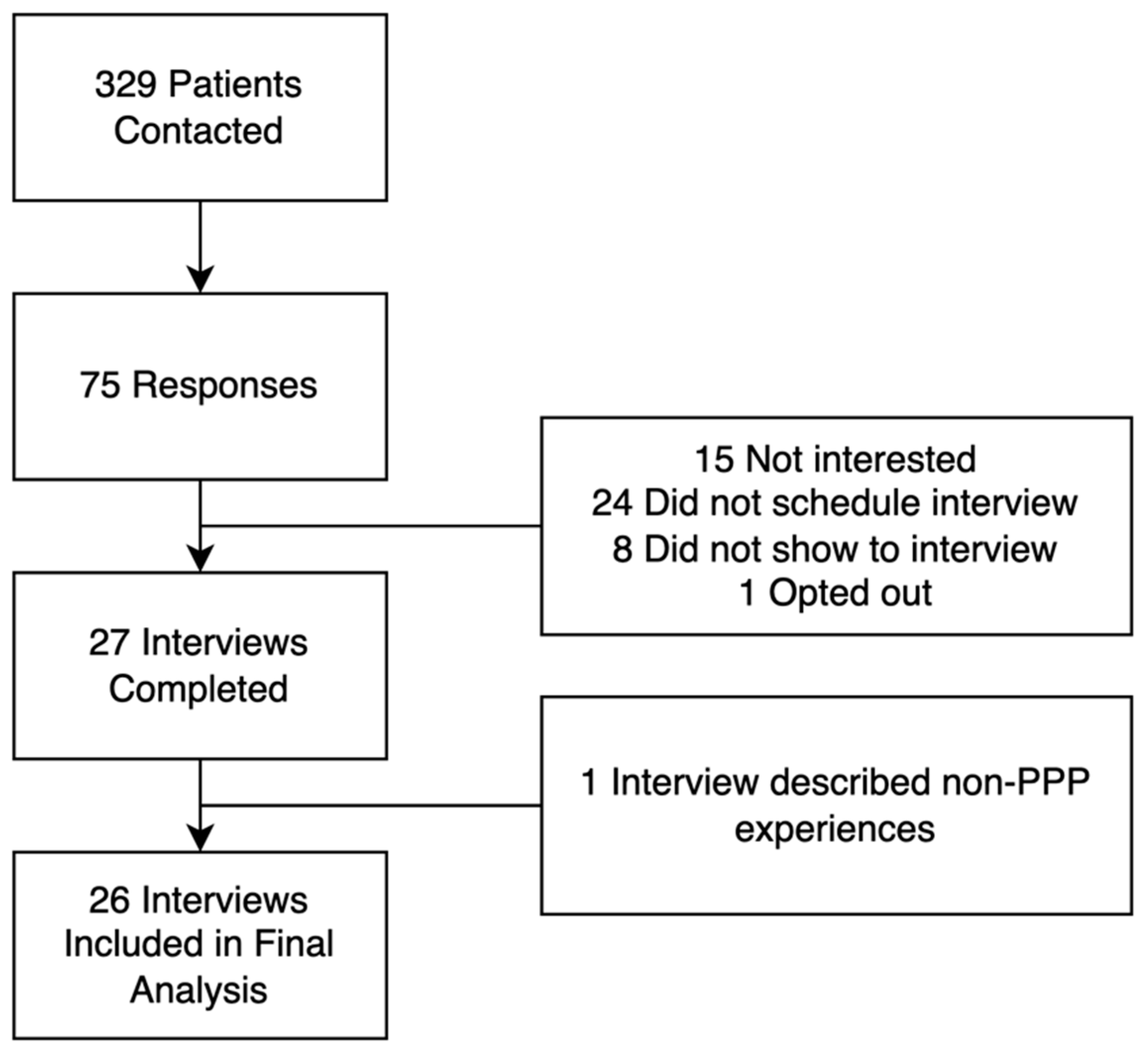

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Qualitative Data

2.4.2. Quantitative Data

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Qualitative

2.5.2. Quantitative

3. Results

4. Qualitative Outcomes

4.1. During Treatment

4.1.1. Initiation of PPP Treatment

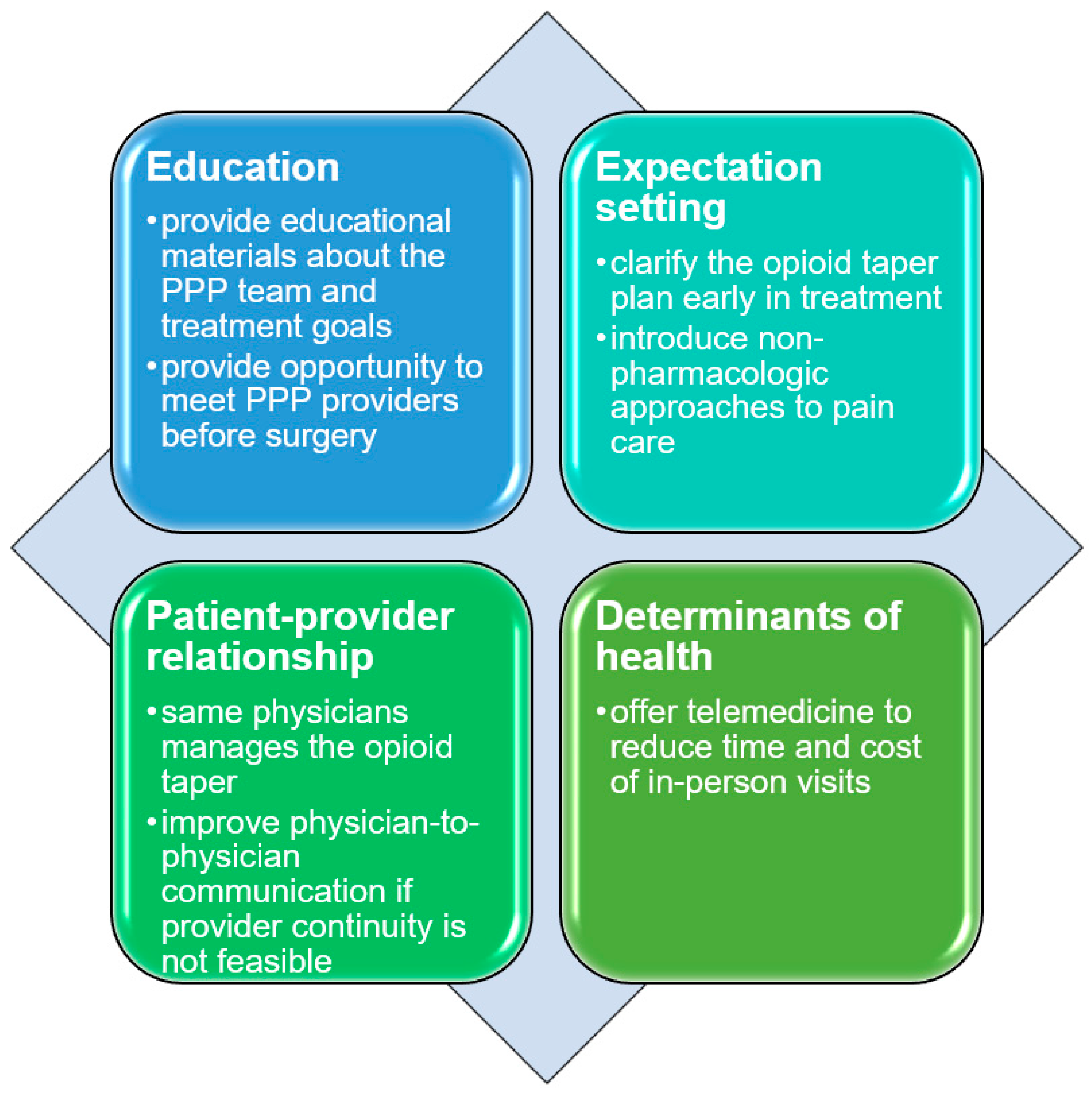

Patient Understanding of PPP Treatment

Patient Expectations of PPP Treatment

4.1.2. General Perceptions and Experiences Receiving Care in the PPP

4.1.3. Patient Engagement

Individualized Care

Patient–Physician Relationship

4.1.4. Psychiatry Co-Treatment in the PPP

4.1.5. Accessibility and Care Coordination of Pain Treatment

4.2. Discharge Planning and Post-Discharge Treatment

4.2.1. Reasons for PPP Discharge and Experiences with Care Transitions

4.2.2. Long-term Outcomes

Clinical Outcomes Associated with PPP Treatment

Treatment Satisfaction

4.3. Quantitative Outcomes

4.3.1. Opioid Use

4.3.2. Patient-Reported Outcomes

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Research & Markets. United States Outpatient Surgical Procedures Market 2019–2023: Rising Number of Outpatient Surgical Procedures in ASCs, HOPDs, and Physicians’ Office. PR Newswire. 2019. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/united-states-outpatient-surgical-procedures-market-2019-2023-rising-number-of-outpatient-surgical-procedures-in-ascs-hopds-and-physicians-office-300783771.html (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Bicket, M.C.; Gunaseelan, V.; Lagisetty, P.; Fernandez, A.C.; Bohnert, A.; Assenmacher, E.; Sequeira, M.; Englesbe, M.J.; Brummett, C.M.; Waljee, J.F. Association of opioid exposure before surgery with opioid consumption after surgery. Reg. Anesthesia Pain Med. 2022, 47, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, J.V.; Cron, D.C.; Lee, J.S.; Gunaseelan, V.M.; Lagisetty, P.M.; Wixson, M.; Englesbe, M.J.; Brummett, C.M.; Waljee, J.F. Classifying preoperative opioid use for surgical care. Ann. Surg. 2020, 271, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waljee, J.F.; Cron, D.C.B.; Steiger, R.M.; Zhong, L.; Englesbe, M.J.; Brummett, C.M. Effect of Preoperative Opioid Exposure on Healthcare Utilization and Expenditures Following Elective Abdominal Surgery. Ann. Surg. 2017, 265, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kha, S.T.; Scheman, J.; Davin, S.; Benzel, E.C. The Impact of Preoperative Chronic Opioid Therapy in Patients Undergoing Decompression Laminectomy of the Lumbar Spine. Spine 2020, 45, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, L.V.; Wang, J.; Padjen, K.; Gover, A.; Rashid, J.; Osmani, B.; Avraham, S.; Kendale, S. Preoperative Long-Acting Opioid Use Is Associated with Increased Length of Stay and Readmission Rates after Elective Surgeries. Pain Med. 2019, 20, 2539–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cron, D.C.; Englesbe, M.J.; Bolton, C.J.; Joseph, M.T.; Carrier, K.L.; Moser, S.E.; Waljee, J.F.; Hilliard, P.E.; Kheterpal, S.; Brummett, C.M. Preoperative Opioid Use is Independently Associated with Increased Costs and Worse Outcomes after Major Abdominal Surgery. Ann. Surg. 2017, 265, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Azam, A.; Segal, S.; Pivovarov, K.; Katznelson, G.; Ladak, S.S.; Mu, A.; Weinrib, A.; Katz, J.; Clarke, H. Chronic postsurgical pain and persistent opioid use following surgery: The need for a transitional pain service. Pain Manag. 2016, 6, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D.B.; Laursen, M.; Edwards, R.R.; Simonsen, O.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Petersen, K.K. The Combination of Preoperative Pain, Conditioned Pain Modulation, and Pain Catastrophizing Predicts Postoperative Pain 12 Months after Total Knee Arthroplasty. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagé, M.G.; Katz, J.; Curtis, K.; Lutzky-Cohen, N.; Escobar, E.M.R.; Clarke, H.A. Acute pain trajectories and the persistence of post-surgical pain: A longitudinal study after total hip arthroplasty. J. Anesthesia 2016, 30, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaghani, S.J.; Lee, D.S.; Bible, J.E.; Archer, K.R.; Shau, D.N.; Kay, H.; Zhang, C.; McGirt, M.J.; Devin, C.J. Preoperative opioid use and its association with perioperative opioid demand and postoperative opioid independence in patients undergoing spine surgery. Spine 2014, 39, E1524–E1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Armaghani, S.; Archer, K.R.; Bible, J.; Shau, D.; Kay, H.; Zhang, C.; McGirt, M.J.; Devin, C. Preoperative Opioid Use as a Predictor of Adverse Postoperative Self-Reported Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Spine Surgery. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014, 96, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzman, C.; Harker, E.C.; Ahmed, R.; Keilin, C.A.; Vu, J.V.; Cron, D.C.; Gunaseelan, V.; Lai, Y.-L.; Brummett, C.M.; Englesbe, M.J.; et al. The Association between Preoperative Opioid Exposure and Prolonged Postoperative Use. Ann. Surg. 2020, 274, e410–e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’donnell, J.A.; Anderson, J.T.; Haas, A.R.; Percy, R.; Woods, S.T.; Ahn, U.M.; Ahn, N.U. Preoperative Opioid Use is a Predictor of Poor Return to Work in Workers’ Compensation Patients after Lumbar Diskectomy. Spine 2018, 43, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilopoulos, T.; Wardhan, R.; Rashidi, P.; Fillingim, R.B.; Wallace, M.R.; Crispen, P.L.; Parvataneni, H.K.; Prieto, H.A.; Machuca, T.N.; Hughes, S.J.; et al. Patient and Procedural Determinants of Postoperative Pain Trajectories. Anesthesiology 2021, 134, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Pagé, M.G.; Weinrib, A.; Clarke, H. Identification of risk and protective factors in the transition from acute to chronic post surgical pain. In Clinical Pain Management; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinrib, A.Z.; Azam, M.A.; Birnie, K.A.; Burns, L.C.; Clarke, H.; Katz, J. The psychology of chronic post-surgical pain: New frontiers in risk factor identification, prevention and management. Br. J. Pain 2017, 11, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.W.; Page, M.G.; Weinrib, A.; Wong, D.; Huang, A.; McRae, K.; Fiorellino, J.; Tamir, D.; Kahn, M.; Katznelson, R.; et al. Predictors of one year chronic post-surgical pain trajectories following thoracic surgery. J. Anesthesia 2021, 35, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrbrand, P.; Phillipsen, A.; Dreyer, P.; Nikolajsen, L. Opioid tapering after surgery: A qualitative study of patients’ experiences. Scand. J. Pain 2020, 20, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, C.W.; Reding, O.; Holmdahl, I.; Keosaian, J.; Xuan, Z.; McAneny, D.; Larochelle, M.; Liebschutz, J. Opioid analgesic use after ambulatory surgery: A descriptive prospective cohort study of factors associated with quantities prescribed and consumed. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Feinberg, A.; McGuiness, B.; Brar, S.; Srikandarajah, S.; Pearsall, E.; McLeod, R.; Clarke, H. Postoperative opioid-prescribing patterns among surgeons and residents at university-affiliated hospitals: A survey study. Can. J. Surg. 2020, 63, E1–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranceanu, A.-M.; Bakhshaie, J.; Reichman, M.; Doorley, J.; Mace, R.A.; Jacobs, C.; Harris, M.; Archer, K.R.; Ring, D.; Elwy, A.R. Understanding barriers and facilitators to implementation of psychosocial care within orthopedic trauma centers: A qualitative study with multidisciplinary stakeholders from geographically diverse settings. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2021, 2, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, S.; Miller, J.; Maccani, M.; Patino, S.; Kaushal, S.; Rieck, H.; Walker, M.; Brummett, C.M.; Bicket, M.C.; Waljee, J.F. Patient risk screening to improve transitions of care in surgical opioid prescribing: A qualitative study of provider perspectives. Reg. Anesthesia Pain Med. 2022, 47, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Weinrib, A.; Fashler, S.R.; Katznelson, R.; Shah, B.R.; Ladak, S.S.; Jiang, J.; Li, Q.; McMillan, K.; Mina, D.S.; et al. The Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service: Development and implementation of a multidisciplinary program to prevent chronic postsurgical pain. J. Pain Res. 2015, 8, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, E.C.; Mariano, E.R.; Narouze, S.; Gabriel, R.A.; Elsharkawy, H.; Gulur, P.; Merrick, S.K.; Harrison, T.K.; Clark, J.D. Making a business plan for starting a transitional pain service within the US healthcare system. Reg. Anesthesia Pain Med. 2021, 46, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.N.; Speed, T.J.; Shechter, R.; Grant, M.C.; Sheinberg, R.; Goldberg, E.; Campbell, C.M.; Theodore, N.; Koch, C.G.; Williams, K. An Innovative Perioperative Pain Program for Chronic Opioid Users: An Academic Medical Center’s Response to the Opioid Crisis. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2019, 34, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D. Building a Transitional Pain Service: Vanderbilt Experience. ASRA News, 1 February 2021; Volume 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admiraal, M.; Hermanides, J.; Hollmann, M.W.; Hermanns, H. Evaluation of Health Care Providers Satisfaction with the Implementation of a Transitional Pain Service. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buys, M.J.; Bayless, K.; Romesser, J.; Anderson, Z.; Patel, S.; Zhang, C.; Presson, A.P.; Brooke, B.S. Opioid use among veterans undergoing major joint surgery managed by a multidisciplinary transitional pain service. Reg. Anesthesia Pain Med. 2020, 45, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.A.; Weinrib, A.Z.; Montbriand, J.; Burns, L.C.; McMillan, K.; Clarke, H.; Katz, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to manage pain and opioid use after major surgery: Preliminary outcomes from the Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service. Can. J. Pain 2017, 1, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeman, T.A.; Buys, M.J.; Bayless, K.; Anderson, Z.; Hales, J.; Brooke, B.S. Complete opioid cessation after surgery improves patient-reported pain measures among chronic opioid users. Surgery 2022, 172, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashler, S.R.; Pagé, M.G.; Svendrovski, A.; Flora, D.B.; Slepian, P.M.; Weinrib, A.Z.; Huang, A.; Fiorellino, J.; Clarke, H.; Katz, J. Predictive Validity and Patterns of Change Over Time of the Sensitivity to Pain Traumatization Scale: A Trajectory Analysis of Patients Seen by the Transitional Pain Service up to Two Years fter Surgery. J. Pain Res. 2022, 15, 2587–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherall, J.; Anderson, J.T.; Anderson, L.A.; Bayless, K.; Anderson, Z.; Brooke, B.S.; Gililland, J.M.; Buys, M.J. A Multidisciplinary Transitional Pain Management Program Is Associated with Reduced Opioid Dependence after Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2022, 37, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechter, R.; Speed, T.J.; Blume, E.; Singh, S.; Williams, K.; Koch, C.G.; Hanna, M.N. Addressing the Opioid Crisis One Surgical Patient at a Time: Outcomes of a Novel Perioperative Pain Program. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2020, 35, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, A.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Speed, T.J.; Villanueva, B.M.; Hanna, B.I.; Slupek, D.A.; Nguyen, J.; Shechter, R.; Hanna, M.N. Patient engagement and prescription opioid use in perioperative pain management. J. Opioid Manag. 2022, 18, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, H.K.; Manoharan, D.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Xie, A.; Shechter, R.; Hanna, M.; Speed, T.J. A multidisciplinary transitional pain service to improve pain outcomes following trauma surgery: A preliminary report. Scand. J. Pain 2022, 23, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G.; Jensen, M.P.; Thornby, J.I.; Shanti, B.F. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J. Pain 2004, 5, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, M.J.L.; Bishop, S.R.; Pivik, J. The pain catastrophizing scale: Development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J., Jr.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHorney, C.A.; Ware, J.E.; Jr Lu, J.F.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med. Care 1994, 32, 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjermstad, M.J.; Fayers, P.M.; Haugen, D.F.; Caraceni, A.; Hanks, G.W.; Loge, J.H.; Fainsinger, R.; Aass, N.; Kaasa, S. Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: A systematic literature review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 41, 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Blasi, Z.; Harkness, E.; Ernst, E.; Georgiou, A.; Kleijnen, J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: A systematic review. Lancet 2001, 357, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.H.; Gbaje, E.; Goydos, R.; Wu, C.L.; Ast, M.; Della Valle, A.G.; McLawhorn, A.; Sculco, P.; Vigdorchik, J.; Cross, M.; et al. Patient perceptions of pain management and opioid use prior to hip arthroplasty. J. Opioid Manag. 2023, 19, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M.; Gnjidic, D.; Lin, C.-W.C.; Jansen, J.; Weir, K.R.; Shaheed, C.A.; Blyth, F.; Mathieson, S. Opioid deprescribing: Qualitative perspectives from those with chronic non-cancer pain. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 4083–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevedal, A.L.; Timko, C.; Lor, M.C.; Hoggatt, K.J. Patient and Provider Perspectives on Benefits and Harms of Continuing, Tapering, and Discontinuing Long-Term Opioid Therapy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 38, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, S.M.; Young, H.M.; Arwood, E.L.; Chou, R.; Herr, K.; Murinson, B.B.; Watt-Watson, J.; Carr, D.B.; Gordon, D.B.; Stevens, B.J.; et al. Core competencies for pain management: Results of an interprofessional consensus summit. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosakowski, S.; Benintendi, A.; Lagisetty, P.; Larochelle, M.R.; Bohnert, A.S.B.; Bazzi, A.R. Patient Perspectives on Improving Patient-Provider Relationships and Provider Communication During Opioid Tapering. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benintendi, A.; Kosakowski, S.; Lagisetty, P.; Larochelle, M.; Bohnert, A.S.; Bazzi, A.R. “I felt like I had a scarlet letter”: Recurring experiences of structural stigma surrounding opioid tapers among patients with chronic, non-cancer pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 222, 108664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hah, J.M.; Trafton, J.A.; Narasimhan, B.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Hilmoe, H.; Sharifzadeh, Y.; Huddleston, J.I.; Amanatullah, D.; Maloney, W.J.; Goodman, S.; et al. Efficacy of motivational-interviewing and guided opioid tapering support for patients undergoing orthopedic surgery (MI-Opioid Taper): A prospective, assessor-blind, randomized controlled pilot trial. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 28, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, J.L.; Dickerson, J.F.; Schneider, J.L.; Firemark, A.J.; Papajorgji-Taylor, D.; Slaughter, M.; Reese, K.R.; Thorsness, L.A.; Sullivan, M.D.; Debar, L.L.; et al. Factors associated with opioid-tapering success: A mixed methods study. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 248–257.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrbrand, P.; Rasmussen, M.M.; Haroutounian, S.; Nikolajsen, L. Shared decision-making approach to taper postoperative opioids in spine surgery patients with preoperative opioid use: A randomized controlled trial. Pain 2021, 163, e634–e641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, D.C.; Flor, H.; Rudy, T.E. Pain and families. I. Etiology, maintenance, and psychosocial impact. Pain 1987, 30, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, D.C.; Kerns, R.D.; Rosenberg, R. Effects of marital interaction on chronic pain and disability: Examining the down side of social support. Rehabil. Psychol. 1992, 37, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Speed, T.J.; Saunders, J.; Nguyen, J.; Khasawneh, A.; Kim, S.; Marsteller, J.A.; McDonald, E.M.; Shechter, R.; et al. The use of telemedicine for perioperative pain management during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.W.; Levy, C.; Matlock, D.D.; Calcaterra, S.L.; Mueller, S.R.; Koester, S.; Binswanger, I.A. Patients’ Perspectives on Tapering of Chronic Opioid Therapy: A Qualitative Study. Pain Med. 2016, 17, 1838–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.G.; Paterniti, D.A.; Feng, B.; Iosif, A.-M.; Kravitz, R.L.; Weinberg, G.; Cowan, P.; Verba, S. Patients’ Experience with Opioid Tapering: A Conceptual Model with Recommendations for Clinicians. J. Pain 2019, 20, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.; Willson, H.; Grange, K. Hopes and fears before opioid tapering: A quantitative and qualitative study of patients with chronic pain and long-term opioids. Br. J. Pain 2021, 15, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goesling, J.; DeJonckheere, M.; Pierce, J.; Williams, D.A.; Brummett, C.M.; Hassett, A.L.; Clauw, D.J. Opioid cessation and chronic pain: Perspectives of former opioid users. Pain 2019, 160, 1131–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.W.; Lovejoy, T.I.; Becker, W.C.; Morasco, B.J.; Koenig, C.J.; Hoffecker, L.; Dischinger, H.R.; Dobscha, S.K.; Krebs, E.E. Patient Outcomes in Dose Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-Term Opioid Therapy: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbain, D.A.; Pulikal, A. Does Opioid Tapering in Chronic Pain Patients Result in Improved Pain or Same Pain vs Increased Pain at Taper Completion? A Structured Evidence-Based Systematic Review. Pain Med. 2019, 20, 2179–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, S.; Smith, C.L.; Dobscha, S.K.; Morasco, B.J.; Demidenko, M.I.; Meath, T.H.; Lovejoy, T.I. Changes in pain intensity after discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain. Pain 2018, 159, 2097–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J.L.; Clark, M.E.; Banou, E. Opioid cessation and multidimensional outcomes after interdisciplinary chronic pain treatment. Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, T.W.; Clark, M.R. Advances in comprehensive pain management. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1996, 19, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menendez, M.E.; Neuhaus, V.; Bot, A.G.J.; Ring, D.; Cha, T.D. Psychiatric disorders and major spine surgery: Epidemiology and perioperative outcomes. Spine 2014, 39, E111–E122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’connell, C.; Azad, T.D.; Mittal, V.; Vail, D.; Johnson, E.; Desai, A.; Sun, E.; Ratliff, J.K.; Veeravagu, A. Preoperative depression, lumbar fusion, and opioid use: An assessment of postoperative prescription, quality, and economic outcomes. Neurosurg. Focus 2018, 44, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasan, A.D.; Butler, S.F.; Budman, S.H.; Benoit, C.; Fernandez, K.; Jamison, R.N. Psychiatric history and psychologic adjustment as risk factors for aberrant drug-related behavior among patients with chronic pain. Clin. J. Pain 2007, 23, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffin, P.O.; Rowe, C.; Oman, N.; Sinchek, K.; Santos, G.-M.; Faul, M.; Bagnulo, R.; Mohamed, D.; Vittinghoff, E. Illicit opioid use following changes in opioids prescribed for chronic non-cancer pain. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berna, C.; Kulich, R.J.; Rathmell, J.P. Tapering Long-term Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: Evidence and Recommendations for Everyday Practice. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, A.; Xing, G.; Tancredi, D.J.; Magnan, E.; Jerant, A.; Fenton, J.J. Association of Dose Tapering with Overdose or Mental Health Crisis Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioids. JAMA 2021, 326, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, M.K.; Sheer, B.R.L.; Mardekian, J.; Masters, E.T.; Patel, N.C.; Hurwitch, A.R.; Weber, J.J.; Jorga, A.; Roland, C.L. Educational intervention for physicians to address the risk of opioid abuse. J. Opioid Manag. 2017, 13, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla-Vaca, A.; Mena, G.E.; Ramirez, P.T.; Lee, B.H.; Sideris, A.; Wu, C.L. Effectiveness of Perioperative Opioid Educational Initiatives: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obstet. Anesthesia Dig. 2022, 134, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeilage, A.G.; Avery, N.S.; Holliday, S.; Glare, P.A.; Ashton-James, C.E. A qualitative trajectory analysis of patients’ experiences tapering opioids for chronic pain. Pain 2022, 163, e246–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R.; Hayes, C.; Boyes, A.W.; Paul, C.L. Integrated Primary Healthcare Opioid Tapering Interventions: A Mixed-Methods Study of Feasibility and Acceptability in Two General Practices in New South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Integr. Care 2020, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, N.S.; Finnie, D.; Warner, D.O.; Hooten, W.M.; Mauck, K.F.; Cunningham, J.L.; Gazelka, H.; Bydon, M.; Huddleston, P.M.; Habermann, E.B. The System Is Broken: A Qualitative Assessment of Opioid Prescribing Practices after Spine Surgery. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Speed, T.; Xie, A.; Shechter, R.; Hanna, M.N. Perioperative Pain Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Telemedicine Approach. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintron, A.; Morrison, R.S. Pain and Ethnicity in the United States: A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 1454–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonora, M.; Perez, H.R.; Heo, M.; Cunningham, C.O.; Starrels, J.L. Race and Gender Are Associated with Opioid Dose Reduction Among Patients on Chronic Opioid Therapy. Pain Med. 2019, 20, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All (n = 26) | Negative Experience (n = 7) | Positive Experience (n = 19) | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 43.5 | (37–56) | 56 | (46–60) | 41 | (35–50) | 0.06 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Female | 20 | 76.9 | 5 | 71.4 | 15 | 78.9 | 1.00 |

| Male | 6 | 23.1 | 2 | 28.6 | 4 | 21.1 | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 21 | 80.8 | 5 | 71.4 | 16 | 84.2 | 0.59 |

| Black | 5 | 19.2 | 2 | 28.6 | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||||

| Single | 10 | 38.5 | 4 | 57.1 | 6 | 31.6 | 0.41 |

| Married | 14 | 53.9 | 3 | 42.9 | 11 | 57.9 | |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 2 | 7.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Education, n (%) | |||||||

| Below college | 16 | 61.5 | 5 | 71.4 | 11 | 57.9 | 0.67 |

| College degree or high | 10 | 38.5 | 2 | 28.6 | 8 | 42.1 | |

| Employment, n (%) | |||||||

| Employed | 7 | 26.9 | 3 | 42.9 | 4 | 21.1 | 0.34 |

| Unemployed/Disabled/Retired | 19 | 73.1 | 4 | 57.1 | 15 | 79.0 | |

| Insurance, n (%) | |||||||

| Private | 18 | 69.2 | 5 | 71.4 | 13 | 68.4 | 1.00 |

| Public | 8 | 30.8 | 2 | 28.6 | 6 | 31.6 | |

| Diagnosis of mood disorder, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 19 | 73.1 | 6 | 85.7 | 13 | 68.4 | 0.63 |

| Yes | 7 | 26.9 | 1 | 14.3 | 6 | 31.6 | |

| Diagnosis of anxiety, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 22 | 84.6 | 7 | 100.0 | 15 | 79.0 | 0.55 |

| Yes | 4 | 15.4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 21.1 | |

| Surgery, n (%) | |||||||

| Cardiac/Thoracic | 2 | 8.7 | 1 | 14.3 | 1 | 6.3 | 0.84 |

| GI/Abdominal | 5 | 21.7 | 1 | 14.3 | 4 | 25.0 | |

| Neuro/ENT | 1 | 4.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.3 | |

| Ortho/Trauma | 11 | 47.8 | 3 | 42.9 | 8 | 50.0 | |

| Plastic/Vascular | 4 | 17.4 | 2 | 28.6 | 2 | 12.5 | |

| No. of PPP visits, median (IQR) | 7.5 | (2–21) | 4 | (2–10) | 8 | (2–30) | 0.30 |

| No. of anesthesia visits, median (IQR) | 2 | (2–7) | 4 | (2–8) | 2 | (1–7) | 0.30 |

| No. of psychiatrist visits, median (IQR) | 1 | (0–8) | 0 | (0–2) | 3 | (0–20) | 0.18 |

| Duration of PPP visits, median (IQR) | 196 | (28–833) | 103 | (28–294) | 252 | (21–1050) | 0.34 |

| Duration of anesthesia visits **, median (IQR) | 42 | (14–217) | 103 | (28–245) | 32 | (0–210) | 0.36 |

| Duration of psychiatrist visits **, median (IQR) | 472.5 | (161–997.5) | 123 | (70–175) | 819 | (224–1029) | 0.13 |

| From Wilcoxon rank sum tests or Fisher’s exact tests | |||||||

| Nodes | Quote | Participant (Age, Race, Sex) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient understanding of PPP treatment | ||

| Understood reason for referral | Q1: “When I first heard about it, it struck me as a highly compassionate and necessary program. Because there are plenty of former opioid users who need surgery and who need to go on opioids to manage their pain. And I think it’s just a brilliant concept.” | P12 (57, C, F) |

| Unclear of reason for referral | Q2: “I guess sometimes I was a little confused about the, I don’t know, the goals of the program or the types of patients they serviced… do I even deserve to be here and be taking up these people’s time.” | P10 (37, C, F) |

| Improve patient education about the PPP | Q3: “… a flyer explaining what this perioperative pain clinic is and the types of specialists you’ll encounter, and the goal of the program, too.” | P10 (37, C, F) |

| Meet PPP team before surgery | Q4: “Once it’s determined that, look, you’re going to have this surgery, maybe that’s an option for them. We’d like to ask you a few questions and see if you wouldn’t want to get involved, or meet with that pain team.” | P15 (52, C, M) |

| Patient expectations of PPP treatment | ||

| Multimodal pain care | Q5: “I was already on high doses of narcotics and…desiring to come off of them… [I expected] weaning [and] adding on multimodal methods of pain management at the same time.” | P14 (43, C, F) |

| Set opioid taper expectations early | Q6: “Like, OK, we’re going to prescribe you narcotics for 30 days, then we’re going to move into other approaches that might be helpful to you. Letting people know what to expect so that there aren’t any surprises.” | P11 (60, C, F) |

| More non-pharmacologic approaches | Q7: “I feel like it might be nice [to have a] discussion of spectrum of services available. [The PPP] focuses mainly on medications… Here are some non-medication related therapies, like massage or acupuncture or things like that.” | P05 (54, C, F) |

| Nodes | Quote | Participant (Age, Race, Sex) |

|---|---|---|

| Unique pain experience | Q8: “When I got into the PPP, the care that I received was so different from anything else that I had ever experienced.” | P07 (72, C, M) |

| Preferred having pain specialist | Q9: “It was really beneficial to feel like I had a physician keeping close watch over me and my recovery who was a bit more of a specialist than my [primary care provider] would have been.” | P10 (37, C, F) |

| Access to pain experts reduced stress | Q10: “It was going to put my mind at ease. Reducing the stress going into surgery, I think, not only my quality, but my wife’s quality, who’s my caretaker. Knowing, her peace of mind, and knowing that we’ve got a team here that’s solely going to watch my pain and manage it appropriately. So, I mean, I think…that peace of mind is immeasurable, really.” | P15 (52, C, M) |

| Benefits of pain and mental health co-treatment | Q11: “My experience had been honestly out of this world for my mental health, you know, to my pain and managing my mental health, you know, and managing my pain through my mental health.” | P24 (45, AA, F) |

| Nodes | Quote | Participant (Age, Race, Sex) |

|---|---|---|

| Individualized Care | ||

| Pain education continued throughout opioid taper | Q12: “[There] was always somebody kind of guiding you… It was helpful to have somebody there with you… reassuring you that it’s a gentle and gradual process, and that you will feel uncomfortable during the process of weaning off of your medications.” | P14 (43, C, F) |

| Pain care tailored to individual’s medical history | Q13: “It put my mind at ease that somebody was monitoring what was going on, somebody knew exactly what has worked, hasn’t worked, and came up with a game plan. [It helped with] reducing the stress going into surgery.” | P15 (52, C, M) |

| Reduced stigma about opioid use | Q14: “I was no longer treated as a drug seeker. I mean, nothing infuriated me more than that… when I was dealing with physicians and surgeons.” | P07 (72, C, M) |

| Patient–physician relationship | ||

| Listened to patients | Q15: “I felt like [the physician] really took the time to just hear my whole [story], it’s a complicated thing.” | P13 (30, C, F) |

| Knowledgeable about pain | Q16: “I think that for the types of therapy that were offered, that people seemed knowledgeable.” | P05 (54, C, F) |

| Clear communication | Q17: “The pain management team [helped us] better understand what was going on, and to come up better game plan and something that was consistent, and I thought that that was a big help.” | P15 (52, C, M) |

| Family engagement | Q18: “You know, my husband came with me quite a few times for visits, and it was nice that he could be there and ask questions himself… And I appreciated because it was easier to explain and to be heard from my family since they knew this was happening. I would definitely say it was good…to bring in a family member with me, that they would be able to get the same information and understanding.” | P16 (44, C, F) |

| Challenges adjusting to new physician’s opioid taper plan | Q19: “After a couple of visits with the original doctor, we agreed according to my history and so on and so forth, that it was gonna take time and we were gonna do a mutually-agreed upon step-down… and then maybe the third visit I see someone different… and [they] said [they] thought I could handle larger step-downs… and that becomes a totally different situation, which wasn’t what I was led to believe I was getting into.” | P03 (60, C, M) |

| Challenges establishing patient–physician relationship with new physician | Q20: “I wish I had kind of stayed with [my first PPP physician]. Because then I felt like I had to re-explain everything from the beginning with [my new physician]. And I didn’t necessarily feel that same comfort level… I felt like I was kind of like jumping past go, you know, without really, really looking at the whole picture.” | P13 (30, C, F) |

| Patients prefer continuity of care with same physician | Q21: “I think it’s always nice if there’s continuity in care with physicians… I had a very nice doctor, and [they] refilled my prescription for the pain meds I was using. Then I was set for a second appointment to come back, and I saw a different doctor… and [they] did not extend my prescription… I think that, if that was the intent, that the first doctor should have told me, okay, we’re going to give you one prescription and move forward from there.” | P11 (60, C, F) |

| Qualities of physician | Q22: “You guys by far have the best doctors there. They are empathetic, the compassion… it really showed, you know, that they care.” | P24 (45, AA, F) |

| Trust | Q23: “I owe the pain center… an enormous debt for this. I look forward to our appointments. I find [the physician] just delightful as a doctor and a person. And I really trust [them].” | P12 (57, C, F) |

| Honesty | Q24: “I was always honest with them… if you’re not honest with them I mean they really can’t help you so you got to be honest. I was honest with them and they made sure to not give me too much or too little.” | P18 (30, C, M) |

| Shared decision-making | ||

| Patient and physician partnered together | Q25: “[The PPP physician] worked with me in helping me manage the postoperative pain and weaning me down from what they had me on—without being judgmental.” | P08 (49, C, F) |

| Individualized opioid taper plan | Q26: “There was a lot of compassion, and also I think the general tone of working with the patient, and not pushing too hard, trying to do within a reasonable amount of time, and working with the patients, I guess, what’s the word, tolerance, in terms of pain levels, what a patient can tolerate day to day and still function. And talking about that.” | P03 (60, C, M) |

| Nodes | Quote | Participant (Age, Race, Sex) |

|---|---|---|

| Whole person approach | Q27: “A lot of doctors, they gloss over, if you say well this is happening, and they just don’t understand how much it is affecting your life. I think that [my psychiatrist has] given me a lot of encouragement and support, and I truly appreciate that.” | P16 (44, C, F) |

| Treating anxiety improves pain | Q28: “[Psychiatrist] put me on a mood stabilizer, which is not something I had ever tried. It’s completely affected my life in the fact that it stopped that really bad anxiety feeling that was causing me incredible pain.” | P20 (41, C, F) |

| Psychotropics improved capacity to work | Q29: “I couldn’t have made it through surgery without it. [The psychiatrist] got me back on antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications. And that has made a huge difference for me. After being unemployed for a good while, like 9 months, I got a great job that I love.” | P12 (57, C, F) |

| Management of substance abuse | Q30: “I think I had one relapse, but it was very short, and it was a one-time thing, and it was impulsive, and I can be a little impulsive… [the psychiatrist] dealt with that pretty well.” | P12 (57, C, F) |

| Interpersonal relationship building | Q31: “I’ve really tried hard to maintain relationships and repair them. And I’m a very, very lucky woman. And again, I owe the pain center and [my psychiatrist] an enormous debt for this.” | P12 (57, C, F) |

| Cognitive behavioral therapies | Q32: “Ways of being, ways of behaving, ways of thinking. So, it wasn’t as simple as they got my narcotic level down…it was really gaining the emotional strength I’d completely forgotten I had.” | P07 (72, C, M) |

| Mindfulness therapies | Q33: “Stretches daily, in the morning and throughout the day. Mind over matter that we talked about. When the pain really gets bad, have a meditation moment. Being more aware of my environment, sounds, smells, trying to tune out the pain.” | P00 (45, AA, F) |

| No interest in mental health treatment | Q34: “I kept getting pushed onto mental health and everyone saying that I needed antidepressants and anti-anxiety and no one would listen to me when I’m like that isn’t the problem. I don’t have those issues.” | P25 (49, C, F) |

| Nodes | Quote | Participant (Age, Race, Sex) |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility of pain treatment and opioids | ||

| Health determinants limited pain care access | Q35: “The biggest downside that I had was just getting access to the clinic itself in the building. I had to pay about 15 dollars for parking every time I came. I added up to 60 dollars a month for the parking there.” | P05 (54, C, F) |

| Recommend telehealth to increase access | Q36: “Now in this day and age, [it would help if there were] options for telehealth visits.” | P01 (36, C, F) |

| Difficulty accessing multiple pain clinics | Q37: “For me, the only issue I had was scheduling conflicts. If I wanted to get an injection, it was hard to get an injection with my work schedule.” | P00 (45, AA, F) |

| Fears that PPP opioid contract would limit access to opioids | Q38: “They had [the patient] sign paperwork saying she wouldn’t see another doctor… And when we tried to reach back out it was challenging to understand if [the patient] could go back to her primary care physician or not. So I think that legality around prescribing narcotics caused a little bit of a challenge there because of the impact to her other medical problems.” | P13 (30, C, F) |

| Patients may not dispose of opioids | Q39: “Do they keep their pain medication after their treatment? We agreed that storing up of medication is something that some people felt an impulse to do. I think that some of the safeguards also cause the hoarding of medication.” | P05 (54, C, F) |

| Biases may influence opioid prescribing | Q40: “I’m a white woman and its easier for me to get pain medication, white privilege and systemic racism. Somebody who’s a young man of color may have a hard time getting pain medication if he needed it.” | P05 (54, C, F) |

| Care coordination of pain treatment and opioids | ||

| Physicians coordinated care with other health systems | Q41: “Before I went back for my follow up, I ended up going into an emergency. I went to another hospital that was closer at the time because of the amount of pain I was in. And when I told [the PPP] what had happened, they were like, Oh my God. And they called the hospital that was working with me, and they got the instruction. So, to me that was positive.” | P22 (40, AA, F) |

| Nodes | Quote | Participant (Age, Race, Sex) |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for PPP discharge | ||

| Able to self-manage pain | Q42: “I just managed it on my own. I definitely didn’t transition to anyone else for that pain. As soon as that surgical pain felt like it was manageable, I stopped going to the clinic and I didn’t see anyone else for that particular pain.” | P10 (37, C, F) |

| Transitioned to local pain clinic | Q43: “Just by trying to help me find a place closer to home that would try and help me. And [the physician] stuck with me until we did, [they] didn’t just drop me.” | P08 (49, C, F) |

| Planned to continue opioids for cancer-related pain | Q44: “I also knew that the radiation oncologist was probably going to put me back on pain medication, even if I got off of [opioids] in what was a very short time frame of… so that was a big ask.” | P03 (60, C, M) |

| Family member encouraged patient to discharge | Q45: “[I thought there would be] different medications that [the physician] was going to put me on that might be able to relieve my pain better… my boyfriend ended up going down with me, and he knew my history with my injuries and stuff like that… he didn’t think it was great, and he was the one who told me not to go back.” | P06 (35, C, F) |

| Experiences with care transitions | ||

| No gaps in pain management | Q46: “I honestly can’t remember how I was quite discharged from the clinic. If it was like “call us if you need us” or what, I can’t remember how that relationship formally ended. But I don’t remember leaving there feeling high and dry or anything.” | P10 (37, C, F) |

| Providers coordinated a warm hand-off with a local pain clinic | Q47: “I’m in a regular pain management program now, eventually trying to wean me off the last of it but I’ve had a few problems with the back surgery since then. But [the PPP] helped me find a long-term pain management doctor down here since I was no longer able to participate in the program.” | P08 (49, C, F) |

| Difficulty obtaining opioids after PPP discharge | Q48: “I ended up having to then get an appointment with my doctor up here to get pain meds and then they don’t want to prescribe them, and they want [the PPP] to prescribe them and [the PPP] won’t prescribe them and it’s an awful stressor that I just don’t think keeps the patient at heart.” | P11 (60, C, F) |

| Reassurance that PPP is an accessible resource | Q49: “That’s something else I got out of the program, was the reassurance that if [stuff] happened, and we all know that it does from time to time, that I had a resource that I could reach for, that I didn’t have to go through the whole thing of who I am, what I am, where I’m at. That kind of understanding… was really wonderful.” | P07 (72, C, M) |

| Nodes | Quote | Participant (Age, Race, Sex) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical outcomes associated with PPP treatment | ||

| Improved quality of life | Q50: “[The PPP] has made my life significantly better. I am not pain-free with surgery-related pain, but it’s significantly improved, and also my sort of overall quality of life has seen a drastic improvement.” | P02 (38, C, F) |

| Pain reduction | Q51: “I never knew that I would be able to have a life with days without pain… I swear you wouldn’t have told me in a million years that I would be in this place with my pain.” | P24 (45, AA, F) |

| Treating anxiety and depression improved pain | Q52: “You know, managing my depression and anxiety has also had a positive side effect on my pain.” | P12 (57, C, F) |

| Treating insomnia improved quality of life | Q53: “I was able to sleep, which is important for quality of life.” | P05 (54, C, F) |

| Learned to practice pain self-management | Q54: “I am a really big believer in distractions. So, I have hobbies… but, if those things aren’t working, then I will either go to heat, or ice, or massage, or something to try to, you know, relieve some of it. I have physical therapists that I go to on a semi-regular basis.” | P16 (44, C, F) |

| Learned about bidirectional relationship between mood and pain | Q55: “One thing I learned about my pain, too, when you sit in it and you dwell in it to me… It gets worse. So, I do try to get up. I try to move around. You know, a lot of self-love, a lot of self-everything. So, I do a lot of that every day, [so] I can get off these meds.” | P24 (45, AA, F) |

| Sustained opioid taper improved quality of life | Q56: “They helped me wean off and see exactly where my threshold was, you know. Being bogged down with all that medicine, you can’t think, and you can’t function the way you need to… I had a cocktail of medicines that I’d been on for a really long time, and [the physician] was able to switch them up, and I have seen a lot of difference between when I first started there and now.” | P16 (44, C, F) |

| Opioid discontinuation improved cognition | Q57: “The pain program has been transformational. This whole piece of regaining some of that lost functioning was borderline miraculous. I could feel myself coming out of a fog that, although I kind of knew I was in, I had no clue as to how deeply I was embedded in that fog, confusion, lack of concentration.” | P07 (72, C, M) |

| Family observed improved functioning after opioid discontinuation | Q58: “I said something to the effect of… ’Do you see some kind of difference?’ And she said, ‘Absolutely.’ And I said, ‘Well, I assume emotionally? I’m conveying an improvement?’ And she said, ‘Definitely. As a matter of fact, the way you are now is much more like the man I married.’” | P07 (72, C, M) |

| Opioid discontinuation improved interpersonal relationships | Q59: “It changed how my family felt about me, they were so excited to have me be free. I’ll never be free from pain but free from opioids.” | P17 (74, C, F) |

| Opioid discontinuation improved work capacity | Q60: “In the infancy of having the pain, and being on the narcotics, it was very easy to have the knee-jerk reaction of I have to take medication, I have to go home. But I can’t go home for work, I have to hold down a job… my quality of life is much improved because I’m off of the narcotics.” | P14 (43, C, F) |

| Improved functioning with low-dose opioids | Q61: “And the fact that I wasn’t taking any pain medication at all made it difficult to sleep, aid my family life, it was difficult, and work was very difficult. And I needed to at least find a functional level. I’m not happy about it; it slows me down, it affects everything that I do; the level of medication I’m on. But, I am functioning better than I was without medication at all; I still have pain every day.” | P03 (60, C, M) |

| Treatment satisfaction | ||

| Met expectations | Q62: “It generally improved my quality of life because it achieved what it was supposed to do, which was get me off of the pain medication.” | P14 (43, C, F) |

| Gratitude for program | Q63: “I have had a very good experience from the pain management part to the therapy I’m getting with [the psychiatrist]…I have had this chronic illness for 23 years now… and this is the only plan that has worked for me…So, I am very grateful and I’m very appreciative and I always tell you know…if it wasn’t for [them], you know, I really don’t know where I would be.” | P24 (45, AA, F) |

| All Study Participants | Negative Experience | Positive Experience | p-Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Post Comparison | ||||||||||

| N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | Two-Group | All | Neg | Pos | |

| Opioid use, MME (mg) | ||||||||||

| First in PPP | 24 | 100.3 ± 123.2 | 7 | 77.1 ± 64.0 | 17 | 109.9 ± 141.2 | 0.82 | |||

| Last in PPP | 24 | 36.6 ± 49.3 | 7 | 30.4 ± 28.7 | 17 | 39.1 ± 56.2 | 0.31 | |||

| At interview | 25 | 31.1 ± 53.0 | 6 | 46.3 ± 63.4 | 19 | 26.3 ± 50.3 | 0.37 | |||

| Change in PPP | 24 | −63.8 ± 109.7 | 7 | −46.8 ± 61.0 | 17 | −70.8 ± 125.5 | 0.61 | 0.004 * | 0.09 | 0.02 * |

| Change from first PPP visit to interview | 23 | −67.0 ± 148.2 | 6 | −28.8 ± 103.7 | 17 | −80.4 ± 161.6 | 0.94 | 0.03 * | 0.29 | 0.05 |

| Change from last in PPP to interview | 23 | −1.5 ± 70.6 | 6 | 21.7 ± 46.5 | 17 | −9.7 ± 76.9 | 0.35 | 0.96 | 0.40 | 0.66 |

| All Study Participants | Negative Experience | Positive Experience | p-Values | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | Two-Group | Pre-Post | ||||

| Pain severity | |||||||||||

| First | 24 | 5.54 ± 2.07 | 7 | 6.04 ± 1.36 | 17 | 5.34 ± 2.30 | 0.36 | ||||

| Last | 24 | 4.65 ± 2.58 | 7 | 6.61 ± 2.48 | 17 | 3.84 ± 2.21 | 0.02 * | ||||

| Change | 24 | −0.90 ± 2.19 | 7 | 0.57 ± 1.37 | 17 | −1.50 ± 2.21 | 0.04 * | 0.10 | |||

| Pain interference | |||||||||||

| First | 24 | 6.70 ± 2.28 | 7 | 7.49 ± 1.69 | 17 | 6.38 ± 2.46 | 0.25 | ||||

| Last | 24 | 4.30 ± 3.19 | 7 | 6.80 ± 3.42 | 17 | 3.28 ± 2.53 | 0.02 * | ||||

| Change | 24 | −2.40 ± 2.46 | 7 | −0.69 ± 2.20 | 17 | −3.10 ± 2.26 | 0.03 * | <0.001 ** | |||

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale | |||||||||||

| First | 24 | 21.54 ± 13.21 | 7 | 27.71 ± 13.47 | 17 | 19.00 ± 12.62 | 0.09 | ||||

| Last | 24 | 17.96 ± 15.30 | 7 | 31.00 ± 16.78 | 17 | 12.59 ± 11.21 | 0.02 * | ||||

| Change | 24 | −3.58 ± 11.16 | 7 | 3.29 ± 11.12 | 17 | −6.41 ± 10.17 | 0.10 | 0.10 | |||

| Insomnia Severity Index | |||||||||||

| First | 24 | 14.33 ± 9.07 | 7 | 13.14 ± 10.96 | 17 | 14.82 ± 8.50 | 0.68 | ||||

| Last | 24 | 12.79 ± 7.55 | 7 | 16.71 ± 7.89 | 17 | 11.18 ± 7.01 | 0.13 | ||||

| Change | 24 | −1.54 ± 9.25 | 7 | 3.57 ± 12.57 | 17 | −3.65 ± 6.91 | 0.31 | 0.17 | |||

| SF-12: Physical Composite Scale | |||||||||||

| First | 25 | 33.62 ± 10.38 | 6 | 35.29 ± 12.20 | 19 | 33.09 ± 10.05 | 0.66 | ||||

| Last | 20 | 35.75 ± 10.34 | 5 | 36.17 ± 11.37 | 15 | 35.61 ± 10.40 | 0.93 | ||||

| Change | 20 | 3.67 ± 10.91 | 5 | 3.01 ± 4.50 | 15 | 3.89 ± 12.47 | 0.90 | 0.19 | |||

| SF-12: Mental Composite Scale | |||||||||||

| First | 25 | 41.75 ± 10.50 | 6 | 33.96 ± 9.21 | 19 | 44.21 ± 9.85 | 0.04 * | ||||

| Last | 20 | 44.88 ± 14.08 | 5 | 32.90 ± 9.59 | 15 | 48.88 ± 13.21 | 0.02 * | ||||

| Change | 20 | 3.04 ± 11.02 | 5 | −3.73 ± 15.09 | 15 | 5.30 ± 8.83 | 0.18 | 0.14 | |||

| SF-36: Physical Composite Scale | |||||||||||

| First | 8 | 32.50 ± 10.31 | 1 | 34.11 | 7 | 32.27 ± 11.11 | |||||

| Last | 6 | 33.64 ± 11.45 | 0 | 6 | 33.64 ± 11.45 | ||||||

| Change | 6 | 2.02 ± 4.05 | 0 | 6 | 2.02 ± 4.05 | 0.25 | |||||

| SF-36: Mental Composite Scale | |||||||||||

| First | 8 | 49.17 ± 14.32 | 1 | 60.21 | 7 | 47.59 ± 14.70 | |||||

| Last | 6 | 54.44 ± 8.57 | 0 | 6 | 54.44 ± 8.57 | ||||||

| Change | 6 | 1.94 ± 7.30 | 0 | 6 | 1.94 ± 7.30 | 0.75 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manoharan, D.; Xie, A.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Flynn, H.K.; Beiene, Z.; Giagtzis, A.; Shechter, R.; McDonald, E.; Marsteller, J.; Hanna, M.; et al. Patient Experiences and Clinical Outcomes in a Multidisciplinary Perioperative Transitional Pain Service. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14010031

Manoharan D, Xie A, Hsu Y-J, Flynn HK, Beiene Z, Giagtzis A, Shechter R, McDonald E, Marsteller J, Hanna M, et al. Patient Experiences and Clinical Outcomes in a Multidisciplinary Perioperative Transitional Pain Service. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2024; 14(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleManoharan, Divya, Anping Xie, Yea-Jen Hsu, Hannah K. Flynn, Zodina Beiene, Alexandros Giagtzis, Ronen Shechter, Eileen McDonald, Jill Marsteller, Marie Hanna, and et al. 2024. "Patient Experiences and Clinical Outcomes in a Multidisciplinary Perioperative Transitional Pain Service" Journal of Personalized Medicine 14, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14010031

APA StyleManoharan, D., Xie, A., Hsu, Y.-J., Flynn, H. K., Beiene, Z., Giagtzis, A., Shechter, R., McDonald, E., Marsteller, J., Hanna, M., & Speed, T. J. (2024). Patient Experiences and Clinical Outcomes in a Multidisciplinary Perioperative Transitional Pain Service. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 14(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14010031