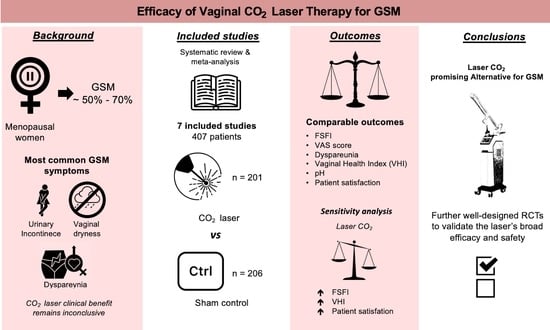

CO2 Laser versus Sham Control for the Management of Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search

- “lasers, gas”[MeSH Terms] OR (“lasers”[All Fields] AND “gas”[All Fields]) OR “gas lasers”[All Fields] OR (“laser”[All Fields] AND “co2”[All Fields]) OR “laser co2”[All Fields]) AND (“vagina”[MeSH Terms] OR “vagina”[All Fields] OR “vaginal”[All Fields] OR “vaginally”[All Fields] OR “vaginals”[All Fields] OR “vaginitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “vaginitis”[All Fields] OR “vaginitides”[All Fields]) AND (“atrophie”[All Fields] OR “atrophy”[MeSH Terms] OR “atrophy”[All Fields] OR “atrophied”[All Fields] OR “atrophies”[All Fields] OR “atrophying”[All Fields].

- “urogenital system”[MeSH Terms] OR (“urogenital”[All Fields] AND “system”[All Fields]) OR “urogenital system”[All Fields] OR “genitourinary”[All Fields]) AND (“syndrom”[All Fields] OR “syndromal”[All Fields] OR “syndromally”[All Fields] OR “syndrome”[MeSH Terms] OR “syndrome”[All Fields] OR “syndromes”[All Fields] OR “syndrome s”[All Fields] OR “syndromic”[All Fields] OR “syndroms”[All Fields]) AND (“menopause”[MeSH Terms] OR “menopause”[All Fields] OR “menopausal”[All Fields] OR “menopaused”[All Fields] OR “menopauses”[All Fields]) AND (“laser s”[All Fields] OR “lasers”[MeSH Terms] OR “lasers”[All Fields] OR “laser”[All Fields] OR “lasered”[All Fields] OR “lasering”[All Fields].

2.4. Selection of Sources of Evidence

Data-Charting Process, Data Items, and Synthesis of Results

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Excluded Studies

3.2. Included Studies

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Patient Characteristics

3.5. Main Outcomes

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Portman, D.J.; Gass, M.L. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: New terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2014, 21, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, E.; Delgado, J.L.; Carmona, F.; Caballero, B.; Guillán, C.; González, P.M.; Suárez-Almarza, J.; Velasco-Ortega, S.; Nieto, C. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Prevalence and quality of life in Spanish postmenopausal women. The GENISSE study. Climacteric 2018, 21, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mension, E.; Alonso, I.; Tortajada, M.; Matas, I.; Gómez, S.; Ribera, L.; Anglès, S.; Castelo-Branco, C. Vaginal laser therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause—Systematic review. Maturitas 2022, 156, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelou, K.; Grigoriadis, T.; Diakosavvas, M.; Zacharakis, D.; Athanasiou, S. The Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: An Overview of the Recent Data. Cureus 2020, 12, e7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffolo, A.F.; Braga, A.; Torella, M.; Frigerio, M.; Cimmino, C.; De Rosa, A.; Sorice, P.; Castronovo, F.; Salvatore, S.; Serati, M. Vaginal Laser Therapy for Female Stress Urinary Incontinence: New Solutions for a Well-Known Issue—A Concise Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitsouni, E.; Grigoriadis, T.; Douskos, A.; Kyriakidou, M.; Falagas, M.E.; Athanasiou, S. Efficacy of vaginal therapies alternative to vaginal estrogens on sexual function and orgasm of menopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 229, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.C.; Leung, C.Y.; Huang, H.L. Comparison of Severity of Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause Symptoms After Carbon Dioxide Laser vs Vaginal Estrogen Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2232563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, Y.; Abdelhakim, A.M.; Labib, K.; Islam, B.A.; Nassar, S.A.; Motaal, A.O.A.; Saleh, D.M.; Abdou, H.; Abbas, A.M.; Mojahed, E.M. Vaginal CO2 laser therapy versus sham for genitourinary syndrome of menopause management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause 2021, 28, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, A.M.; Dockter, T.; Le-Rademacher, J.; Salani, R.; Hudson, C.; Hundley, A.; Terstriep, S.; Streicher, L.; Faubion, S.; Loprinzi, C.L.; et al. Pilot study of fractional CO2 laser therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause in gynecologic cancer survivors. Maturitas 2021, 144, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruanphoo, P.; Bunyavejchevin, S. Treatment for vaginal atrophy using microablative fractional CO2 laser: A randomized double-blinded sham-controlled trial. Menopause 2020, 27, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruff, J.; Khandwala, S. A Double-Blind Randomized Sham-Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of Fractional Carbon Dioxide Laser Therapy on Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause. J. Sex Med. 2021, 18, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.G.; Maheux-Lacroix, S.; Deans, R.; Nesbitt-Hawes, E.; Budden, A.; Nguyen, K.; Lim, C.Y.; Song, S.; McCormack, L.; Lyons, S.D.; et al. Effect of Fractional Carbon Dioxide Laser vs Sham Treatment on Symptom Severity in Women With Postmenopausal Vaginal Symptoms: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 326, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatore, S.; Pitsouni, E.; Grigoriadis, T.; Zacharakis, D.; Pantaleo, G.; Candiani, M.; Athanasiou, S. CO2 laser and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause: A randomized sham-controlled trial. Climacteric 2021, 24, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mension, E.; Alonso, I.; Anglès-Acedo, S.; Ros, C.; Otero, J.; Villarino, Á.; Farré, R.; Saco, A.; Vega, N.; Castrejón, N.; et al. Effect of Fractional Carbon Dioxide vs Sham Laser on Sexual Function in Survivors of Breast Cancer Receiving Aromatase Inhibitors for Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: The LIGHT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2255697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.S.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Verhaeghe, J.; Latul, Y.P.; Housmans, S.; Deprest, J. Laser versus sham for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: A randomised controlled trial. Bjog 2023, 130, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Kacker, R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: An update. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2007, 28, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozo, S.P.; Djulbegovic, B.; Hozo, I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2005, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, W.; Chen, F.; Xu, T.; Fan, Q.; Shi, H.; Kang, J.; Shi, X.; Zhu, L. A randomized controlled study of vaginal fractional CO2 laser therapy for female sexual dysfunction. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.G.; Fuchs, T.; Deans, R.; McCormack, L.; Nesbitt-Hawes, E.; Abbott, J.; Farnsworth, A. Vaginal epithelial histology before and after fractional CO2 laser in postmenopausal women: A double-blind, sham-controlled randomized trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 229, 278.e271–278.e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraiso, M.F.R.; Ferrando, C.A.; Sokol, E.R.; Rardin, C.R.; Matthews, C.A.; Karram, M.M.; Iglesia, C.B. A randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen therapy in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause: The VeLVET Trial. Menopause 2020, 27, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, V.L.; Steiner, M.L.; Pompei, L.M.; Strufaldi, R.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; Santiago, L.H.S.; Wajsfeld, T.; Fernandes, C.E. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial for evaluating the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser compared with topical estriol in the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2018, 25, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, P.; Heinke, T.; Pinho, S.C.; Focchi, G.R.A.; Tso, F.K.; de Almeida, B.C.; Silva, I.; Speck, N.M.G. Comparison of topical fractional CO2 laser and vaginal estrogen for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome in postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2021, 28, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politano, C.A.; Costa-Paiva, L.; Aguiar, L.B.; Machado, H.C.; Baccaro, L.F. Fractional CO2 laser versus promestriene and lubricant in genitourinary syndrome of menopause: A randomized clinical trial. Menopause 2019, 26, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, L.B.; Politano, C.A.; Costa-Paiva, L.; Juliato, C.R.T. Efficacy of Fractional CO2 Laser, Promestriene, and Vaginal Lubricant in the Treatment of Urinary Symptoms in Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Lasers Surg. Med. 2020, 52, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faubion, S.S.; Sood, R.; Kapoor, E. Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: Management Strategies for the Clinician. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1842–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugulytė, N.; Žukienė, G.; Bartkevičienė, D. Emerging Use of Vaginal Laser to Treat Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause for Breast Cancer Survivors: A Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åsberg, R.E.; Giskeødegård, G.F.; Raj, S.X.; Karlsen, J.; Engstrøm, M.; Salvesen, Ø.; Nilsen, M.; Lundgren, S.; Reidunsdatter, R.J. Sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment, and body image in Norwegian breast cancer survivors: A 12-year longitudinal follow-up study and comparison with the general female population. Acta Oncol. 2023, 62, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Wyld, L.; Krishnaswamy, P.H. The Impact of Vaginal Laser Treatment for Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer 2019, 19, e556–e562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothes, A.R.; Runnebaum, M.; Runnebaum, I.B. Ablative dual-phase Erbium:YAG laser treatment of atrophy-related vaginal symptoms in post-menopausal breast cancer survivors omitting hormonal treatment. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 144, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, S.; Cardozo, L.; Ruffolo, A.F.; Athanasiou, S. Laser versus sham for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: A randomised controlled trial - Some crucial criticalities. Bjog 2023, 130, 1697–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, S.; Pitsouni, E.; Falagas, M.E.; Salvatore, S.; Grigoriadis, T. CO2-laser for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. How many laser sessions? Maturitas 2017, 104, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitsouni, E.; Grigoriadis, T.; Falagas, M.; Tsiveleka, A.; Salvatore, S.; Athanasiou, S. Microablative fractional CO2 laser for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause: Power of 30 or 40 W? Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1865–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippini, M.; Porcari, I.; Ruffolo, A.F.; Casiraghi, A.; Farinelli, M.; Uccella, S.; Franchi, M.; Candiani, M.; Salvatore, S. CO2-Laser therapy and Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sex Med. 2022, 19, 452–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year; Author | Country | Type of Study | Inclusion Criteria | Treatment Details | Outcomes Measured | Type of Laser |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023; Mension [17] | Spain | DB-RCT | Breast cancer survivors, age ≥ 30 yrs, aromatase inhibitors (for ≥6 months), menopause, signs or symptoms of GSM with dyspareunia, vaginal pH ≥ 5, willingness for sexual activity; no use of vaginal lubricants or moisturizers for 30 days; no vaginal hormonal treatment for 6 mo; no radiofrequency, laser treatment, hyaluronic, or lipofilling in the vagina for 2 years; no ospemifene treatment; no intraepithelial neoplasm of cervix, vagina, or vulva; no active genital tract infection; no prior treatment for genital cancer; no organ prolapse ≥ stage II; no positive test results for human papillomavirus | 5 sessions, 4-week intervals | FSFI, dyspareunia, body image, quality of life, VHI, vaginal pH, VMI, VET, VEE, adverse effects, tolerance | Microablative CO2 laser system, SmartXide2 V2LR, MonaLisa Touch (DEKA Laser) with 40 W power, 1000 μs dwell time, 1000 μm dot spacing, SmartStack 2 on double pulse emission mode |

| 2023; Page [18] | Belgium | DB-RCT | Moderate-to-severe GSM symptoms; MBS score ≥ 2; no acute or recurrent urogenital infections; no prolapse grade ≥ 3; no hormonal replacement therapy for the last 6 months; no vaginal estrogen, moisturizers, lubricants, homeopathic preparations, or physiotherapy for pelvic floor disorders for the last 3 months; no previous vaginal laser therapy | 3 sessions, 4-week intervals | Relief of most bothersome symptom (dryness, itching, burning, dyspareunia, dysuria)—scale 0–3, VAS, patient satisfaction, FSFI, ICIQ-OAB, adverse events, VHI, vaginal pH, vaginal architecture | Fractional microablative CO2, SmartXide2 V2LR Monalisa Touch (DEKA, Florence, Italy) laser with 30 W power, 1000 ms dwell time, 1000 mm dot spacing, SmartStack 2.0 |

| 2021; Cruff [14] | USA | DB-RCT | Menopausal or post bilateral oophorectomy status; moderate-to-severe dyspareunia or vaginal dryness; vaginal health index (VHI)<15 and vaginal pH > 5; POP-Q stage < III; no pelvic reconstructive surgery 6 months before; no malignancy; no acute or recurrent genital tract infections; no serious diseases or chronic conditions; no estrogen use for 3mo prior; no use of moisturizers, lubricants, or homeopathic preparations in past 14 days; willingness to discontinue lubricants or estrogens | 3 sessions, 6-week intervals | FSFI, DIVA, UDI-6, PGI-I, VAS for GSM symptoms, dyspareunia | Fractional microablative CO2 laser MonaLisa Touch Vagina: 30 W power, 1000 ms dwell time, 1000 mm dot spacing, SmartStack 1–3 Vulva: 26 W power, 800 ms, 800 mm dot spacing, SmartStack 1 |

| 2021; Li [15] | Australia | DB-RCT | Age ≥18 years; no previous vaginal energy-based treatment for GSM; amenorrhea ≥ 12 mo (naturally or iatrogenically); vaginal symptoms: dyspareunia, burning, itching, or dryness; ineffective previous treatment or contraindicated (personal lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, or estrogen); discontinuation of vaginal estrogen for 6 months before inclusion; no prolapse ≥ stage II; no active genital or urinary tract infections; no previous vaginal mesh surgery; no ongoing medical conditions | 3 sessions, 4-week intervals (min 4 weeks; max 8 weeks) | Change in symptom severity, dyspareunia, dysuria, vaginal dryness, burning, itching (VAS), VSQ, VHI, VMI, vaginal biopsy |

Laser CO2 (SmartXide V2LR, MonaLisa Touch, DEKA Laser)

40 W power, 1000 μs dwell time, 1000 μm dot spacing, SmartStack 2 on DP emission mode, delivering fluence of 5.37 J/cm2 |

| 2020; Ruanphoo [13] | Thailand | DB-RCT | Age ≥ 50 years; last menstruation at least 1 year ago; no hormonal therapy within the past 6 months; no vaginal moisturizer or lubricant for 30 days; no acute/recurrent urinary tract infection; no active genital infection; genital hiatus ≥ 2 cm; no prolapse stage ≥ 2 | 3 sessions, 4-week intervals | VAS for symptoms, vaginal health index, ICIQ-VS, adverse events, patient satisfaction | The laser settings were DEKA pulse mode, 40 W power, 1000 ms dwell time, 1000 mm dot spacing, SmartStack parameter 1–3 |

| 2021; Salvatore [16] | Italy, Greece | DB-RCT | Postmenopausal women with dryness and dyspareunia related to GSM; no vulvodynia; no vulvovaginitis; no vulvovaginal pathology; no prior treatment with energy-based devices; no use of non-hormonal/hormonal local therapies; no prolapse stage > 2 | 3 sessions, 4-week intervals | VAS, FSFI, UDI-6, changes in dryness, dyspareunia | Microablative fractional CO2 laser (SmartXide2 V2LR Monalisa Touch; DEKA, Florence, Italy) Vagina: 30 W power, 1000 ls dwell time, 1000 lm dot spacing, SmartStack 1–3; D-pulse mode; pulse energy, 43.2 mJ, 86.4 mJ, and 129.6 mJ at the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd sessions, respectively; Introitus and labia minora: 24 W power, 400 ls dwell time, 1000 lm spacing, SmartStack parameter 1; D-pulse mode; fluence, 2.36 J/cm2; pulse energy, 23.2 mJ |

| 2020; Quick [12] | USA | SB-RCT | History of cervical, endometrial, vaginal, vulvar or ovarian cancer with dyspareunia and/or vaginal dryness, unable to be sexually active due to pain, completed all cancer-related treatment prior 6 months, no recurrent or metastatic cancer, no prolapse stage ≥ 2, no prior reconstructive pelvic surgery with mesh, no hormone therapy 6 weeks before treatment | 3 sessions, 4-week intervals | VAS, vulvar assessment scales, FSFI, UDI-6, patient satisfaction, adverse events | Fractional microablative CO2 (Monalisa Touch, DEKA, Florence, Italy) Vagina: 30 W power, 1000 μs dwell time, 1000 mm dot spacing, SmartStack 1 and 3 Vestibule: 26 W power, 800 μs dwell time, 800 μm dot spacing, SmartStack 1 |

| Year; Author | Patient No | Age (Years) | Parity | Sexually Active (Initially) | Years of Menopause | Iatrogenic-Induced Menopause | Lubrication Use/MHT | Follow-Up (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023; Mension [17] | CLT (CO2) vs. SLT (sham) 35 vs. 37 | 51.3 ± 7.8 vs. 53.7 ± 8.8 | N/A | 25 vs. 27 | N/A | 26 vs. 20 | N/A | 6 months |

| 2023; Page [18] | 29 vs. 29 | 57.4 ± 7.07 vs. 56.2 ± 6.3 | N/A | N/A | 6.85 ± 5.41 vs. 7.3 ± 5.22 | 9 vs. 9 | 5 vs. 5 | 3 months |

| 2021; Cruff [14] | 12 vs. 16 | 61 (54-66) vs. 59 (56-65) a | 2 (2–3) vs. 2 (2–3) | 12 vs. 13 | 14 (5–24) vs. 10 (4–15) a | N/A | 5 vs. 5 (estrogen) | 6 months |

| 2021; Li [15] | 43 vs. 42 | 55 ± 7 vs. 58 ± 8 | 4 vs. 6 nulliparous | 23 vs. 21 | 8 (4–14) vs. 6 (3–9) (median IQR) | 20 vs. 21 | N/A | 12 months |

| 2020; Ruanphoo [13] | 44 vs. 44 | 61.73 ± 8.01 vs. 59.84 ± 7.49 | 2.11 ± 1.51 vs. 2.20 ± 1.53 | 10 vs. 24 | N/A | N/A | N/A 10 vs. 8 | 3 months |

| 2021; Salvatore [16] | 28 vs. 30 | 57 ± 6.9 vs. 58.4 ± 6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 months |

| 2020; Quick [12] | 10 vs. 8 | 56 ± 11.17 vs. 56.8 ± 5.95 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 vs. 1 N/A | 4 months |

| Year; Author | Patient No | Vaginal Assessment Scale for GSM Symptoms * | UDI-6 * | FSFI * | VHI * | VAS Dyspareunia (Scale 0–10) * | Satisfaction (Patient No) ** | Vaginal pH * | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023; Mension [17] | 35 vs. 37 | N/A | N/A | 5.2 ± 1.5 a vs. 7.9 ± 1.2 a | 3.3 ± 4.1 a vs. 5 ± 4.5 a | −4.3 ± 3.4 a vs. −4.5 ± 2.3 a | N/A | −0.6 ± 0.9 a vs. −0.8 ± 1.2 a | N/A |

| 2023; Page [18] | 29 vs. 29 | −0.61 ± 0.84 a vs. −0.364 ± 0.73 a | N/A | 3.51 ± 6.22 a vs. 3.14 ± 7.71 a | 2.9 ± 4.21 a vs. 1.24 ± 4.23 a | −2.31 ± 4.51 a vs. −2.17 ± 3.45 a | 12/29 vs. 10/29 | 0.02 ± 0.64 a vs. 0.12 ± 0.44 a | No serious, minor vaginal bleeding, spotting or discharge |

| 2021; Cruff [14] | 12 vs. 16 | N/A | −18.8 (−37.5 to 8.3) b vs. −8.3 (−16.7 to 8.3) b | 6.4 (−2.1 to 17.7) b vs. 6.6 (2.8 to 12.3) b | 3 (0 to 6) b vs. 5 (0 to 7) b | N/A | N/A | N/A | No |

| 2021; Li [15] | 43 vs. 42 | N/A | N/A | N/A N/A | 0.9 (−2.2 to 4) c vs. 1.3 (−1.4 to 4) c | −28.8 (−67.7 to 10) c vs. −4 (−35.3 to 27.4) c (scale 0−100) | N/A | N/A | 16 vs. 17 (vaginal pain/discomfort, spotting, lower urinary tract symptoms, lower or upper urinary tract infection, vaginal discharge) |

| 2020; Ruanphoo [13] | 44 vs. 44 | −0.44 ± 0.66 a vs. 0.04 ± 0.63 a | N/A | N/A | −3.27 ± 0.78 a vs. −1.42 ± −0.36 a | N/A | 31/39 vs. 17/38 | N/A | Vaginal bleeding 0 vs. 1 Vaginal discharge 3 vs. 1 Vaginitis 1 vs. 0 Pain after procedure 3 vs. 4 |

| 2021; Salvatore [16] | 28 vs. 30 | N/A | −8 ± 15.3 a vs. −2.6 ± 9.6 a | 12.3 ± 8.9 a vs. 2.4 ± 4.9 a | N/A | −6 ± 2.6 a vs. −1.1 ± 1.8 a | N/A | N/A | Mild vulva irritation 28 (laser group) |

| 2020; Quick [12] | 10 vs. 8 | −3 ± 1.7 a vs. −2 ± 3.5 a | −25 ± 28.3 a vs. −4.18 ± 13.3 a | 7.025 ± 5.51 a vs. −1.68 ± 3.4 a | N/A | N/A | 6/6 vs. 1/6 | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prodromidou, A.; Zacharakis, D.; Athanasiou, S.; Kathopoulis, N.; Varthaliti, A.; Douligeris, A.; Michala, L.; Athanasiou, V.; Salvatore, S.; Grigoriadis, T. CO2 Laser versus Sham Control for the Management of Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13121694

Prodromidou A, Zacharakis D, Athanasiou S, Kathopoulis N, Varthaliti A, Douligeris A, Michala L, Athanasiou V, Salvatore S, Grigoriadis T. CO2 Laser versus Sham Control for the Management of Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13(12):1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13121694

Chicago/Turabian StyleProdromidou, Anastasia, Dimitrios Zacharakis, Stavros Athanasiou, Nikolaos Kathopoulis, Antonia Varthaliti, Athanasios Douligeris, Lina Michala, Veatriki Athanasiou, Stefano Salvatore, and Themos Grigoriadis. 2023. "CO2 Laser versus Sham Control for the Management of Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials" Journal of Personalized Medicine 13, no. 12: 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13121694

APA StyleProdromidou, A., Zacharakis, D., Athanasiou, S., Kathopoulis, N., Varthaliti, A., Douligeris, A., Michala, L., Athanasiou, V., Salvatore, S., & Grigoriadis, T. (2023). CO2 Laser versus Sham Control for the Management of Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(12), 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13121694