Abstract

Background: The association between cerebral aneurysms and left atrial myxoma is known but rare. We described its pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnostic findings and treatment using a systemic review of the literature. Methods: MEDLINE via PubMed was searched for articles published until August 2022 using the keywords “atrial myxoma”, “cardiac myxoma” and “cerebral aneurysm”. Results: In this review, 55 patients with multiple myxomas aneurysms were analyzed, and 65% were women. The average age when aneurysms were diagnosed was 42.5 ± 15.81; most patients were less than 60 years old (86%). Aneurysms could be found before the diagnosis, at the same time as cardiac myxoma, or even 25 years after resection of the atrial mass. In our review, the mean time to diagnoses was 4.5 years. Our review estimates that the most common symptoms were vascular incidents (25%) and seizures (14.3%). In 15 cases, variable headaches were reported. Regarding management strategies, 57% cases were managed conservatively as the primary choice. Conclusions: Although cerebral aneurysms caused by atrial myxoma are rare, the long-term consequences can be serious and patients should be monitored.

1. Introduction

Cardiac myxomas (CM) are the most common benign “cardiac” tumors, accounting for up to 30–50% of all primary heart tumors [1]. The incidence is approximately 0.5–1 cases per 1,000,000 population per year [2]. About 75% concern the left atrium of the heart [3], and 18% originate in the right atrium; biatrial myxomas are rare and account for less than 2.5% of all cardiac myxomas. Myxomas are particularly frequent from the third to the sixth decades of life; the ratio women: men varies from 2:1 to 3:1. CM are diagnosed based on clinical examination and tests such as electrocardiography (ECG), transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE), transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), chest computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cardiac MRI [4].

Most cardiac myxomas present with constitutional, embolic and obstructive manifestations. Younger and male patients have more neurologic symptoms, and female patients have more systemic symptoms. These can cause many neurological complications, including systemic embolism, cerebral infarction, cerebral cavernous malformations and intracranial aneurysms [5]. Myxoma-related aneurysms are always multiple and in most cases have a fusiform-shape.

Left atrial myxomas are considered curable by complete resection and give excellent results in long-term follow-up. Surgical excision remains the treatment of choice for cardiac myxoma. Early diagnosis and intervention is desirable because of the persistent risk of brain metastases and aneurysms. However, incomplete resection, multifocal tumors and embolism caused by tumors are important factors in its recurrence and complications [3,6]. Currently, our understanding of cerebral aneurysms caused by atrial myxoma is based mainly on case reports.

This systemic review of the literature aimed to provide an exhaustive summary of available case reports evaluating medical history, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic methods in patients with cerebral aneurysms caused by atrial myxoma.

2. Methods

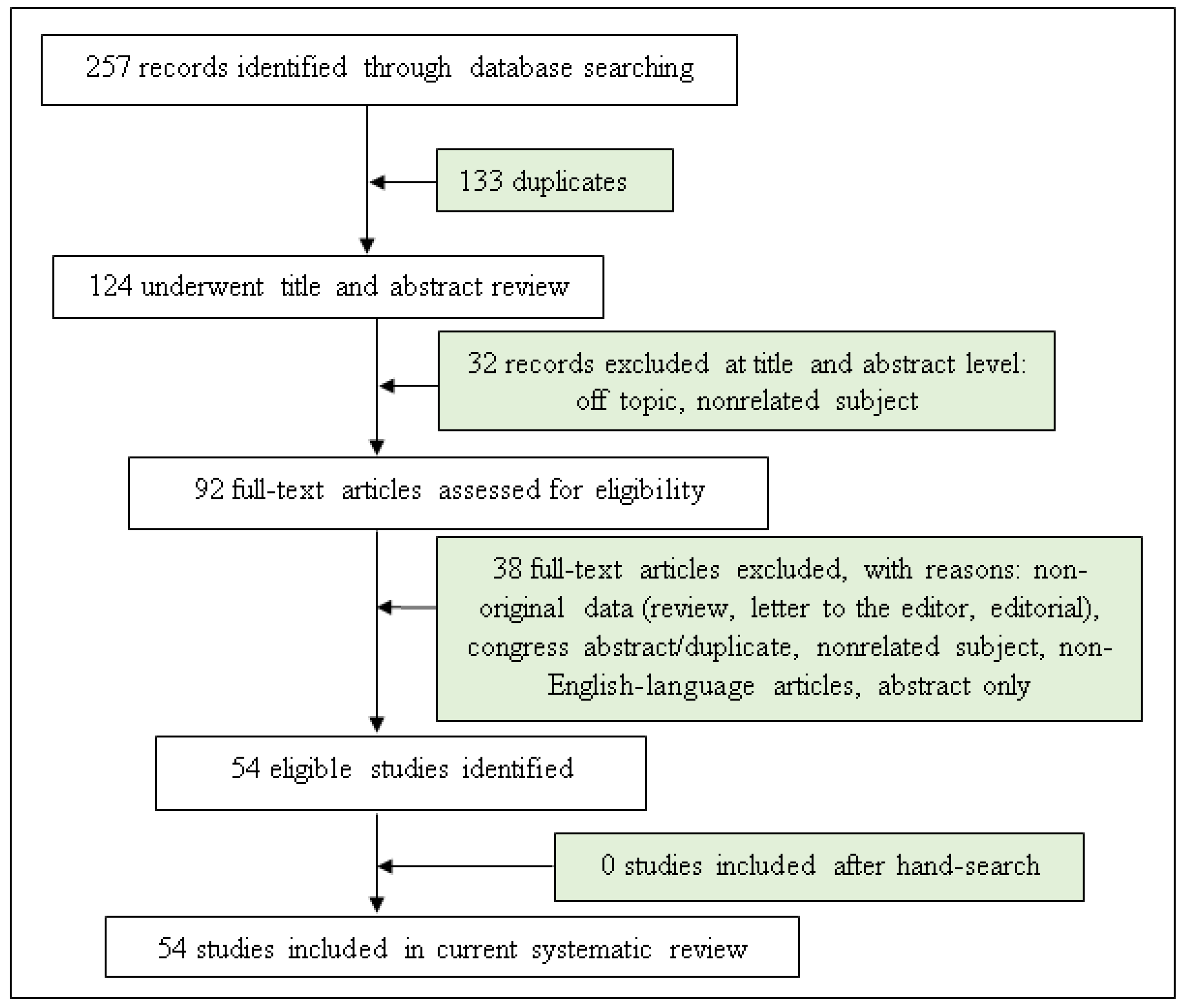

JCŁ and MWP performed an independent online search in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [7] using the following combination of keywords: “atrial” and “cardiac” and “myxoma” and “cerebral” and “aneurysm” or “myxomatosus” and “cerebral” and “aneurysm”.

We considered publication records from MEDLINE and ERIC databases until August 2022. In addition, the reference lists from eligible publications were searched. All discrepancies were resolved by discussing the results of the preliminary search with a third reviewer (SB) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

A total of 257 records were identified and screened separately by the authors. Then, these record lists were double read by both analysts and 92 abstracts were found to be relevant to the subject. Each researcher worked independently and prepared their own list of relevant full-text manuscripts. Both lists were compared and 54 publications were found to be the most relevant to the study and included in this review. The exclusion criteria were non-English-language articles, conference papers and abstract only.

3. Results

We found 54 case report articles describing 55 patients. All cases are illustrated in Table 1. We did not find any article about type case series or an original work on a larger group of patients. The group consisted of 35 women (64%) and 20 men (36%). The average age when aneurysms were diagnosed was 42.5 ± 15.81 years (the age varied from 11 to 69 years) and 46 of the patients were less than 60 years old (84%).

Table 1.

Overview of cases of cerebral aneurysms in atrial myxoma from the literature.

Aneurysms could be found before the diagnosis, at the same time as cardiac myxoma, or even 25 years after resection of atrial mass. In our review, the mean time to diagnoses was 4.5 years. In 1 patient, the myxoma was localized in both atrial, while in the remaining 54 patients—left atrium.

Our review estimates that the most common symptoms were vascular incidents (TIA, stroke), seizures, vertigo or dizziness and loss of consciousness. In 15 cases, variable headaches were reported—most often they had the migraine phenotype with visual disturbances. Three patient presented clinical symptoms typical of subarachnoid hemorrhage and two had no symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2.

The most common clinical symptoms.

Based on our analyses, trial myxoma-associated aneurysms are most often localized to the entire area of vascularization, followed by middle cerebral arteries, posterior cerebral arteries, anterior cerebral arteries and finally the basilar artery (Table 3).

Table 3.

Location of brain aneurysm.

All patients underwent successful surgical resection of the cardiac myxoma. Regarding management strategies, 33 patients (60%) were managed conservatively as the primary choice. In three cases (5.5%) there was chemotherapy treatment; in one case, radiotherapy. One patient was treated with stereotactic radiosurgery.

4. Discussion

Cardiac myxomas are the most common benign cardiac tumor in adults [58]. Myxoma cells most likely arise from resident pluripotent or multipotent mesenchymal stem cells, the embryonic remnants of which differentiate into endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and other mesenchymal cells and this explains the most common occurrence of myxomas in the atrial septum [58,59]. Myxomas of the heart are most common in adults between the third and sixth decades of life. They can occur sporadically (more often in women) or be familial [1,2,58]. Familial occurrence has been shown to be associated with an autosomal dominant mutation of the PRKAR1A gene located on chromosome 17q2 [59,60]. Familial myxomas are usually multiple, recurrent and located outside the left atrium [61].

The genetic basis of intracranial aneurysms is very complex. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the extracellular matrix surrounding cerebral vessels, as well as the role of matrix metalloproteinases [62,63]. Studies on the genetics of aneurysms have been aimed at elucidating causative genes or discovering new loci associated with aneurysm risk. Genome-wide association studies have used single nucleotide polymorphism data to discover several susceptibility loci, including the SOX17 and CDKN2A genes. The proteins encoded by these genes regulate endothelial function and blood vessel formation and so genetic variation that affects the extracellular matrix may have the greatest impact on the risk of aneurysms [62,64].

The clinical picture of CM includes symptoms due to embolism, intracardiac obstruction, size, location and mobility of the tumor [1,59]. Patients with small tumors may remain asymptomatic for years, or nonspecific symptoms may mimic systemic or cardiovascular disease [58].

Embolism associated with detachment of tumor fragments or thrombi occurs in 10–50% of patients with cardiac myxomas [59,65]. There has been no correlation between the risk of embolism and tumor size and some authors have suggested an association of such complications with chest trauma [66]. Most commonly, embolisms involve the cerebral arteries, where cavernous malformations and aneurysms can develop. Neurological complications are a very broad group of symptoms that include fainting and loss of consciousness, headache and dizziness, seizures, transient cerebral ischemia, stroke or rupture of aneurysms or vascular malformations [5,8,51]. Women in their fifth decade of life are most at risk for embolic stroke and acute embolic stroke may be the first manifestation of atrial myxoma in a young patient [58,59]. Sudden loss of consciousness after strenuous exercise is particularly important in the patient’s history [58]. Embolism of the coronary artery is rare, and it is even believed that the coronary arteries are relatively resistant to embolism due to anatomical conditions [1,65,67]. Braun et al. [61] showed from their analysis that only 40 cases of myocardial infarction due to myxoma have been documented in the literature.

The etiology of myxomatous cerebral aneurysms is still unknown [40,59]. A few hypotheses have been put forward in terms of the pathogenesis of aneurysms. Based on the literature, two main theories can be identified. First, a neoplastic process theory proposes that myxoma cells adhere to and penetrate the endothelium, then grow in the subintimal layer and destroy the arterial wall. However, it should be remembered that the metastatic hypothesis does not imply a typical tumor metastasis process. By definition, cardiac myxomas are not malignant tumors and therefore do not have potential to “metastasize” in the strict sense of the word. The second theory is the “vascular damage theory” proposed by Sloane et al. in 1966, where the temporary occlusion of cerebral vessels by myxoma cells causes damage to the endothelium, which is followed by an alteration of hemodynamics and promotion of aneurysm formation [68,69,70].

Myxoma cells produce and release proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6), which is an important factor of aneurysm initiation [18]. Recent studies suggest that autocrine production of IL-6 by myxoma plays a main role in the embolization of the myxomatous cell. Elevated IL-6 levels have been detected in patients with myxomatous aneurysms, before and even after myxoma resection. It has been known that atrial myxoma cells are capable of producing IL-6. Recent studies have shown that there is a connection between overproduction of Il-6 and cerebral aneurysm development. A persistent elevated IL-6 level induces overexpression of multiple proteolytic enzymes (such as metalloproteinase), which can weaken cerebral vessel walls and lead to aneurysm formation [55,71]. Based on this theory, cardiac myxoma resection is usually accompanied by a reduction in serum IL-6 levels, but a few studies have shown new aneurysm formation after the myxoma resection still showed persistently elevated IL-6 levels. Formation of a cerebral aneurysm is also associated with overproduction of Il-6 by an emboli tumor, that induces degradation of the extracellular matrix in the intracranial vessels and is connected with an increased level of IL-6 in cerebrospinal fluid. So, IL-6 has two ways of impacting the formation of the aneurysm’s direction, first by promoting tumor invasion into the intracranial artery or secondly by increasing the chance of a distant embolization of the cardiac myxoma [55,57,71].

The natural history of this kind of aneurysm is also not clear; some cases have shown stability, others have shown improvement (self-occlusion) and others have shown an increased number and enlargement of aneurysms [5,51,57]. In most cases, the first neurological manifestation of atrial myxomas is complications due to cerebral embolism and subsequent cerebral infarction [2,59,65]. Vascular incidents (transient cerebral ischemia, stroke), which were observed in 36.3% of the patients of this review, should be precisely associated with embolism. Aneurysm formation and subsequent subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage are rare but are the most well-known complications of atrial myxoma in adults [5]. Even the presence of multiple but unruptured cerebral vascular aneurysms usually does not produce clinical symptoms. However, up to half of patients with cerebral aneurysms may experience so-called “predictive headaches,” the exact cause of which is not known, but is thought to be related to microbleeding from aneurysms or other vascular malformations [69,72,73]. The other symptoms that were observed in the patients analyzed in this review included seizures, headaches or dizziness that could be related to microbleeding from aneurysms or could be a symptom related to compression of malformations on central nervous system structures. Given some nonspecific but nevertheless quite suggestive clinical signs, it is necessary to screen for cerebral complications in patients with atrial myxoma.

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of aneurysms caused by cardiac myxomas, but a conservative approach and radiological follow-up is recommended. The majority of reported cases have demonstrated stability and some have even been documented as exhibiting spontaneous regression [12]. Routine radiological follow-up by MRI examination is needed to monitor the eventual progression of the aneurysms [72,73]. A lot of therapeutic methods are available, ranging from endovascular methods, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation or a combination of these. Only enlarged or ruptured aneurysms may require invasive management and must be evaluated for endovascular or neurosurgical intervention [4].

The atrial myxoma should be excised as soon as possible after the diagnosis to prevent further complications such as systemic embolization, constitutional symptoms (fever, fatigue, weight loss) or obstruction of the mitral valve [44,58,59]. Surgical resection of the cardiac myxoma also eliminates the early neurologic symptoms, most frequently ischemic cerebral infarcts. Although the cardiac resection of the atrial tumor minimizes the risk of embolization, it does not decrease the risk of the formation of a delayed cerebral aneurysm. This results from the theory of “metastasis and infiltrate”. Intracranial aneurysms may continue to grow despite the surgical removal of the atrial myxoma [53,67].

The current literature describes several different surgical options. Cases of ruptured aneurysms are generally considered as urgent surgical procedures. Clipping or coiling are not applicable for myxomatous aneurysms because they are multiple, located at distal vessels, fusiform and without a neck. The literature provides a few reports about clipping of large aneurysms [54]. Aneurysms might keep growing after endovascular coil embolization [31].

Open surgical treatment is recommended for a lesion-caused mass effect or in cases of single saccular aneurysms. A bypass is recommended for lesions with good collateral compensation and it is a reasonable option when sacrifice of the feeding artery may be required. Compared with other options, this procedure is technically challenging and is limited because it is difficult to apply in a variety of locations where aneurysms may occur [33].

Chemotherapy as a treatment was introduced by Roeltgen et al. in 1981 [74]. They tried doxorubicin in conjunction with surgery for recurrent atrial myxoma. In some cases, etoposide and carboplatin were also used [13,50]. Chemotherapy may protect patients against aneurysm growth [13]. Low-dose radiation in combination with chemotherapy has been reported as an effective method for degradation of metastasis [5,12,13]. A new option is frameless stereotactic radiosurgery (SRT), which is less invasive than endovascular or open surgery, avoids the systemic effects of chemotherapy, and limits toxicity to surrounding brain parenchyma compared to whole brain irradiation [5].

5. Conclusions

Cerebral aneurysms are rare complications of cardiac myxoma, which can appear many years after cardiologic treatment. They are twice as common in middle-aged women. The entire area of vascularization is most often located in the area of the middle cerebral artery. Vascular incidents, unspecific headaches and seizures are their most common clinical manifestations; their rupture and subarachnoid hemorrhages are relatively rare. We do not have any treatment guidelines as yet, however, in the case of myxoma aneurysms a long-term observation is recommended.

Therefore, long-term follow-up of patients with cardiac myxomas for possible co-occurrence of cerebral aneurysms and their complications is very important. In addition, patients with multiple cerebral aneurysms, especially those with a cardiac burden, should be alert to the possibility of cardiac myxoma.

Author Contributions

J.C.-Ł.—conceptualized and wrote the manuscript; S.B.—reviewed the manuscript; M.W.-P.—conceptualized, wrote and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported by Wroclaw Medical University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of The Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Wroclaw Medical University.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACA | anterior cerebral artery |

| CT | computed tomography |

| CTA | computed tomography angiography |

| DSA | digital subtraction angiography |

| ICA | internal carotid artery |

| MCA | middle cerebral artery |

| MRA | magnetic resonance angiography |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| PCA | posterior cerebral artery |

| PICA | posterior inferior cerebellar artery |

| SWI | susceptibility weighted imaging |

References

- McManus, B. Primary tumors of the heart. In Braunwald’ s Heart Disease, A Text Book of Cardiovascular Medicine, 9th ed.; Mann, D.L., Douglas, P.Z., Libby, P., Bonow, R.O., Eds.; Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 1638–1650. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, S.K.; Barik, R.; Sarma, T.; Iyer, V.R.; Sai, V.; Mishra, J.; Voleti, C.D. Clinical presentation and investigation findings in cardiac myxomas: New insights from the developing world. Am. Heart J. 2007, 154, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Du, H.; Zhang, L.; Guo, S.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; He, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Mao, L.; et al. Multiple cerebral metastases and metastatic aneurysms in patients with left atrial Myxoma: A case report. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanidis, G.; Khoury, M.; Balanika, M.; Perrea, D.N. Current challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of cardiac myxoma. Kardiol Pol. 2020, 78, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hau, M.; Poon, T.L.; Cheung, F.C. Neurological manifestations of atrial myxoma and stereotactic radiosurgery for metastatic aneurysms. J. Radiosurg. SBRT 2020, 6, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Li, X. Multiple cerebral aneurysms associated with cardiac myxoma. J. Card Surg. 2019, 34, 860–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrohimi, A.; Putko, B.N.; Jeffery, D.; Van Dijk, R.; Chow, M.; McCombe, J.A. Cerebral Aneurysm in Association with Left Atrial Myxoma. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 46, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asranna, A.P.; Kesav, P.; Nagesh, C.; Sreedharan, S.E.; Kesavadas, C.; Sylaja, P.N. Cerebral aneurysms and metastases occurring as a delayed complication of resected atrial Myxoma: Imaging findings including high resolution Vessel Wall MRI. Neuroradiology 2017, 59, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashalatha, R.; Moosa, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Krishna Manohar, S.R.; Sandhyamani, S. Cerebral aneurysms in atrial myxoma: A delayed, rare manifestation. Neurol. India 2005, 53, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baikoussis, N.G.; Siminelakis, S.N.; Kotsanti, A.; Achenbach, K.; Argyropoulou, M.; Goudevenos, J. Multiple cerebral mycotic aneurysms due to left atrial myxoma: Are there any pitfalls for the cardiac surgeon? Hellenic J. Cardiol. 2011, 52, 466–468. [Google Scholar]

- Bernet, F.; Stulz, P.M.; Carrel, T.P. Long-term remission after resection, chemotherapy, and irradiation of a metastatic myxoma. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1998, 66, 1791–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branscheidt, M.; Frontzek, K.; Bozinov, O.; Valavanis, A.; Rushing, E.J.; Weller, M.; Wegener, S. Etoposide/carboplatin chemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic myxomatous cerebral aneurysms. J. Neurol. 2014, 261, 828–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.L.; Ye, W.; Miao, Z.R.; Song, Q.B.; Ling, F. Multiple intracranial aneurysms as delayed complication of atrial myxoma. Case Rep. Lit. Rev. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2005, 11, 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, D.H.; Chan, N.; Choy, C.; Chu, P.; Yuen, H.; Lau, C.; Lo, Y.; Tsui, P.; Mok, N. A lady with atrial myxoma presenting with myocardial infarction and cerebral aneurysm. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 172, e16–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desousa, A.L.; Muller, J.; Campbell, R.; Batnitzky, S.; Rankin, L. Atrial myxoma: A review of the neurological complications, metastases, and recurrences. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1978, 41, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddleman, C.S.; Gottardi-Littell, N.R.; Bendok, B.R.; Batjer, H.H.; Bernstein, R.A. Rupture of cerebral myxomatous aneurysm months after resection of the primary cardiac tumor. Neurocrit. Care 2010, 13, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezerioha, N.; Feng, W. Intracardiac Myxoma, Cerebral aneurysms and elevated Interleukin-6. Case Rep. Neurol. 2015, 7, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, P.L.; Haglund, F.; Bhogal, P.; Yeo Leong Litt, L.; Södermann, M. The dynamic natural history of cerebral aneurysms from cardiac myxomas: A review of the natural history of myxomatous aneurysms. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2018, 24, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, K.; Sasaki, T.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Okada, Y.; Fujimaki, T.; Kirino, T. Histologically verified cerebral aneurysm formation secondary to embolism from cardiac myxoma. Case Rep. J. Neurosurg. 1995, 83, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, K.J.; Rennie, A.; Saxena, A. Multiple cerebral aneurysms secondary to cardiac myxoma. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 26, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.M.; Agrawal, N. Oncotic cerebral aneurysms in a case of left atrial myxoma, role of imaging in diagnostics and treatment. Pol. J. Radiol. 2015, 80, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Herbst, M.; Wattjes, M.P.; Urbach, H.; Inhetvin-Hutter, C.; Becker, D.; Klockgether, T.; Hartmann, A. Cerebral embolism from left atrial myxoma leading to cerebral and retinal aneurysms: A case report. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2005, 26, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iskandar, M.E.; Dimitrova, K.; Geller, C.M.; Hoffman, D.M.; Tranbaugh, R.F. Complicated sporadic cardiac myxomas: A second recurrence and myxomatous cerebral aneurysms in one patient. Case Rep. Surg. 2013, 2013, 642394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanović, B.A.; Tadić, M.; Vraneš, M.; Orbović, B. Cerebral aneurysm associated with cardiac myxoma: Case report. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2011, 11, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jean, W.C.; Walski-Easton, S.M.; Nussbaum, E.S. Multiple intracranial aneurysms as delayed complications of an atrial myxoma: Case report. Neurosurgery 2001, 49, 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, S.A.; Johnston, S.C. Multiple stable fusiform intracranial aneurysms following atrial myxoma. Neurology 2005, 64, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, E.-A.; Lee, W.; Chung, J.W.; Park, J.H. Multiple cerebral and coronary aneurysms in a patient with left atrial myxoma. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 28, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.-H.; Kim, T.-G.; Kim, O.-J.; Oh, S.-H. Multiple fusiform cerebral aneurysms and highly elevated serum interleukin-6 in cardiac myxoma. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2009, 45, 394–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, P.; Rajaraman, K.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Das, S. Multiple fusiform distal aneurysms in an operated case of atrial myxoma: Case report and review of literature. Neurol. India 2013, 61, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarow, F.; Aktan, S.; Lanier, K.; Agola, J. Coil embolization of an enlarging fusiform myxomatous cerebral aneurysm. Radiol. Case Rep. 2018, 13, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shang, H.; Zhou, D.; Liu, R.; He, L.; Zheng, H. Repeated embolism and multiple aneurysms: Central nervous system manifestations of cardiac myxoma. Eur. J. Neurol. 2008, 15, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namura, O.; Saitoh, M.; Moro, H.; Watanabe, H.; Sogawa, M.; Nishikura, K.; Hayashi, J.-I. A case of biatrial multiple myxomas with glandular structure. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 13, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oguz, K.K.; Firat, M.M.; Cila, A. Fusiform aneurysms detected 5 years after removal of an atrial myxoma. Neuroradiology 2001, 43, 990–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oomen, A.W.; Kuijpers, S.H. Cerebral aneurysms one year after resection of a cardiac myxoma. Neth. Heart J. 2013, 21, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Quan, K.; Song, J.; Zhu, W.; Chen, L.; Pan, Z.; Li, P.; Mao, Y. Repeated multiple intracranial hemorrhages induced by cardiac myxoma mimicking cavernous angiomas: A case report. Chin. Neurosurg. J. 2017, 3, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, D.L.; Lanpher, A.B.; Klein, J.M.; Kozakewich, H.P.W.; Kahle, K.T.; Smith, E.R.; Orbach, D.B. Multimodal treatment approach in a patient with multiple intracranial myxomatous aneurysms. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2018, 21, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radoi, M.P.; Stefanescu, F.; Arsene, D. Brain metastases and multiple cerebral aneurysms from cardiac myxoma: Case report and review of the literature. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 26, 893–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryou, K.S.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Park, J.; Hwang, S.-K.; Hamm, I.-S. Multiple fusiform myxomatous cerebral aneurysms in a patient with Carney complex. J. Neurosurg. 2008, 109, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabolek, M.; Bachus, R.; Arnold, G.; Storch, A.; Bachus-Banaschak, K. Multiple cerebral aneurysms as delayed complication of left cardiac myxoma: A case report and review. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2005, 111, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffie, P.; Riquelme, F.; Mura, J.; Urra, A.; Passig, C.; Castro, Á.; Illanes, S. Multiple myxomatous aneurysms with bypass and clipping in a 37-year-old man. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2015, 24, e69–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillan, A.; Sigounas, D.; Fink, M.E.; Gobin, Y.P. Multiple fusiform intracranial aneurysms 14 years after atrial myxoma resection. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 1204–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Saji, N.; Kobayashi, K.; Shibazaki, K.; Kimura, K. A case of cerebral embolism due to cardiac myxoma presenting with multiple cerebral microaneurysms detected on first MRI scans. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2016, 56, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sedat, J.; Chau, Y.; Dunac, A.; Gomez, N.; Suissa, L.; Mahagne, M. Multiple cerebral aneurysms caused by cardiac myxoma. A case report and present state of knowledge. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2007, 13, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorenson, T.J.; Brinjikji, W.; Lanzino, G. Giant Fusiform Intracranial Aneurysm in Patient with History of Myxoma. World Neurosurg. 2019, 128, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Tewari, P. Stroke associated with left atrial mass: Association of cerebral aneurysm with left atrial myxoma. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2014, 17, 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, K. Multiple cerebral aneurysms in a patient with recurrent cardiac myxomas. A case report. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2004, 10, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveinsson, O.; Herrman, L. Multiple cerebral aneurysms in a patient with cardiac myxoma: What to do? BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2013200767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamulevičiūtė, E.; Taeshineetanakul, P.; Terbrugge, K.; Krings, T. Myxomatous aneurysms: A case report and literature review. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2011, 17, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vontobel, J.; Huellner, M.; Stolzmann, P. Cerebral ‘metastasizing’ cardiac myxoma. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waliszewska-Prosół, M.; Zimny, A.; Chojdak-Łukasiewicz, J.; Zagrajek, M.; Paradowski, B. Multiple fusiform cerebral aneurysms detected after atrial myxoma resection: A report of two cases. Kardiol. Pol. 2018, 76, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Kilani, R.; Toye, L.R. Central and peripheral fusiform aneurysms six years after left atrial myxoma resection. J Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Y. Multiple intracranial aneurysms followed left atrial myxoma: Case report and literature review. J. Thorac. Dis. 2013, 5, E227–E231. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, M.B.; Akin, Y.; Güray, Ü.; Kisacik, H.L.; Korkmaz, S. Late recurrence of left atrial myxoma with multiple intracranial aneurysms. Int. J. Cardiol. 2003, 87, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokomuro, H.; Yoshihara, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Shiono, N.; Koyama, N.; Takanashi, Y. The variations in the immunologic features and interleukin-6 levels for the surgical treatment of cardiac myxomas. Surg. Today 2007, 37, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Ji, Z.Y.; Shi, S.S. Atrial myxoma presenting with multiple intracranial fusiform aneurysms: A case report. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2015, 115, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, Z.; Qiao, Q.; Mahmood, F.; Feng, Y. Anesthesia management of atrial myxoma resection with multiple cerebral aneurysms: A case report and review of the literature. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020, 20, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaravaza, D.R.; Lalla, U.; Zaharie, S.D.; de Jager, L.J. Unusual Presentation of Atrial Myxoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am. J. Case Rep. 2021, 22, e931437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynen, K. Cardiac myxomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Wang, S.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Z.; Ma, L.; Liao, X.; Li, Q. Neurological manifestations of atrial myxoma: A retrospective analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 4635–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Schrötter, H.; Reynen, K.; Schwencke, C.; Strasser, R.H. Myocardial infarction as complication of left atrial myxoma. Int. J. Cardiol. 2005, 101, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagra, A.; Williams, E.; Aghili-Mehrizi, S.; Goutnik, M.A.; Martinez, M.; Turner, R.C.; Lucke-Wold, B. Pediatric Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Rare Events with Important Implications. Brain Neurol. Disord. 2022, 5, 020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, D.; Small, C.; Lucke-Wold, B.; Dodd, W.S.; Chalouhi, N.; Hu, Y.C.; Hosaka, K.; Motwani, K.; Martinez, M.; Polifka, A.; et al. Understanding the genetics of intracranial aneurysms: A primer. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2022, 212, 107060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foroud, T.; Koller, D.L.; Lai, D.; Sauerbeck, L.; Anderson, C.; Ko, N.; Deka, R.; Mosley, T.H.; Fornage, M.; Woo, D.; et al. FIA Study Investigators. Genome-wide association study of intracranial aneurysms confirms role of Anril and SOX17 in disease risk. Stroke 2012, 43, 2846–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waikar, H.D.; Jayakrishnan, A.G.; Bandusena, B.S.N.; Priyadarshan, P.; Kamalaneson, P.P.; Ileperuma, A.; Neema, P.K.; Dhawan, R.; Chaney, M.A. Left atrial myxoma presenting as cerebral embolism. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2020, 34, 3452–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.C.; Trivedi, A. Widespread systemic and peripheral embolization of left atrial myxoma following blunt chest trauma. Conn. Med. 2017, 81, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Al Zahrani, I.M.; Alraqtan, A.; Rezk, A.; Almasswary, A.; Bella, A. Atrial myxoma related myocardial infarction: Case report and review of the literature. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 2014, 26, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sloane, L.; Allen, J.H.; Collins, H.A. Radiologic observations in cerebral embolization from left heart myxoma. Radiology 1966, 87, 262e6. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, V.H.; Connolly, H.M.; Brown, R.D., Jr. Central nervous system manifestations of cardiac myxoma. Arch. Neurol. 2007, 64, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinede, L.; Duhaut, P.; Loire, R. Clinical presentation of left atrial cardiac myxoma. A series of 112 consecutive cases. Medicine 2001, 80, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, C.E.; Rosado, M.F.; Bernal, L. The role of interleukin-6 in cases of cardiac myxoma. Clinical features, immunologic abnormalities, and a possible role in recurrence. Tex. Heart. Inst. J. 2001, 28, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nucifora, P.G.; Dillon, W.P. MRI diagnosis of myxomatous aneurysms: Report of two cases. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2001, 22, 1349–1352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chiang, K.-H.; Cheng, H.-M.; Chang, B.-S.; Chiu, C.-H.; Yen, P.-S. Multiple cerebral aneurysms as manifestations of cardiac myxoma: Brain imaging, digital subtraction angiography, and echocardiography. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2011, 23, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeltgen, D.P.; Weimer, G.R.; Patterson, L.F. Delayed neurologic complications of left atrial myxoma. Neurology 1981, 31, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).