Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques—A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

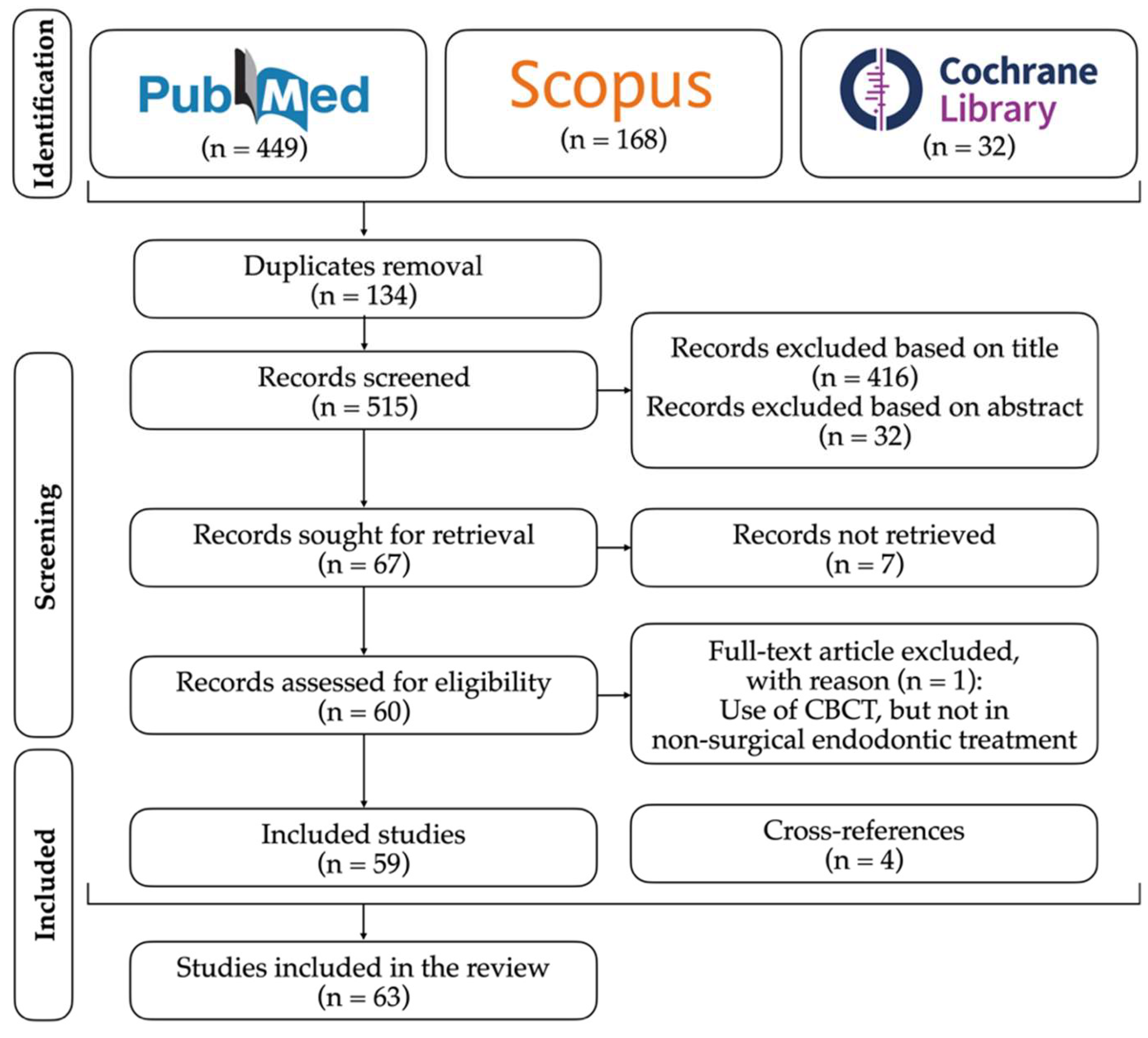

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zehnder, M.S.; Connert, T.; Weiger, R.; Krastl, G.; Kühl, S. Guided Endodontics: Accuracy of a Novel Method for Guided Access Cavity Preparation and Root Canal Location. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubizarreta-Macho, Á.; Valle Castaño, S.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Mena-Álvarez, J. Effect of Computer-Aided Navigation Techniques on the Accuracy of Endodontic Access Cavities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biology 2021, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Casadei, B.A.; de Lara-Mendes, S.T.O.; de Barbosa, F.M.C.; Araújo, C.V.; Freitas, C.A.; Machado, V.C.; Santa-Rosa, C.C. Access to Original Canal Trajectory after Deviation and Perforation with Guided Endodontic Assistance. Aust. Endodon. J. 2020, 46, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, P.S.; Dummer, P.M.H. Pulp Canal Obliteration: An Endodontic Diagnosis and Treatment Challenge. Int. Endod. J. 2012, 45, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, R.; Reich, S.; Connert, T.; Kess, S.; Soliman, S.; Reymus, M.; Krastl, G. Guided Endodontics: A Comparative in Vitro Study on the Accuracy and Effort of Two Different Planning Workflows. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2020, 23, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Buchgreitz, J.; Bjørndal, L.; Sobrinho, A.P.R.; Tavares, W.L.; Kinariwala, N.; Maia, L.M. Static Guided Nonsurgical Approach for Calcified Canals of Anterior Teeth. In Guided Endodontics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 113–133. ISBN 9783030552817. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca Tavares, W.L.; Diniz Viana, A.C.; de Carvalho Machado, V.; Feitosa Henriques, L.C.; Ribeiro Sobrinho, A.P. Guided Endodontic Access of Calcified Anterior Teeth. J Endod. 2018, 44, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjitkar, S.; Taylor, J.; Townsend, G. A Radiographic Assessment of the Prevalence of Pulp Stones in Australians. Aust. Dent. J. 2002, 47, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinagre, A.; Castanheira, C.; Messias, A.; Palma, P.J.; Ramos, J.C. Management of Pulp Canal Obliteration—Systematic Review of Case Reports. Medicina 2021, 57, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.D.; Carrico, C.K.; Bermanis, I. 3-Dimensional Accuracy of Dynamic Navigation Technology in Locating Calcified Canals. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta-Macho, Á.; Ferreiroa, A.; Agustin-Panadero, R.; Rico-Romano, C.; Lobo-Galindo, A.B.; Mena-Alvarez, J. Endodontic Re-Treatment and Restorative Treatment of a Dens Invaginatus Type II through New Technologies. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, 55840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta Macho, Á.; Ferreiroa, A.; Rico-Romano, C.; Alonso-Ezpeleta, L.Ó.; Mena-Álvarez, J. Diagnosis and Endodontic Treatment of Type II Dens Invaginatus by Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography and Splint Guides for Cavity Access. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2015, 146, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Arslan, H. Guided Endodontics: A Case Report of Maxillary Lateral Incisors with Multiple Dens Invaginatus. Restor Dent Endod 2019, 44, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Arslan, H.; Jethani, B. Conservative Management of Type II Dens Invaginatus with Guided Endodontic Approach: A Case Series. J. Conserv. Dent. 2019, 22, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.J.N.L.; De-Deus, G.; Souza, E.M.; Belladonna, F.G.; Cavalcante, D.M.; Simões-Carvalho, M.; Versiani, M.A. Present Status and Future Directions–Minimal Endodontic Access Cavities. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 531–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, B.S.; Dhesi, M.; Makdissi, J. Computer-Aided Dynamic Navigation: A Novel Method for Guided Endodontics. Quint. Int. 2019, 50, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandak, M.; Chandak, M.; Rathi, C.; Khatod, S.; Chandak, P.; Relan, K. Guided Endodontics: A Novel Invasive Technique For Access Cavity Preparation -Review. I. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 11, 3459–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Wealleans, J.; Ray, J. Endodontic Applications of 3D Printing. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirani, C.; Spinelli, A.; Marchetti, C.; Gandolfi, M.G.; Zamparini, F.; Prati, C.; Pellegrino, G. Use of Dynamic Navigation with an Educational Interest for Finding of Root Canals. G Ital. Endod. 2020, 34, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, G.; Habib, M.; Tohme, H.; Patel, S.; Bordone, A.; Perez, C.; Zogheib, C. Guided Endodontic Treatment of Calcified Lower Incisors: A Case Report. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, C.; Keles, A. Digital Applications in Endodontics. J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2021, 38, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontiev, W.; Bieri, O.; Madörin, P.; Dagassan-Berndt, D.; Kühl, S.; Krastl, G.; Krug, R.; Weiger, R.; Connert, T. Suitability of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Guided Endodontics: Proof of Principle. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, P.J.; Martins, J.; Diogo, P.; Sequeira, D.; Ramos, J.C.; Diogenes, A.; Santos, J.M. Does Apical Papilla Survive and Develop in Apical Periodontitis Presence after Regenerative Endodontic Procedures? Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, P.J.; Marques, J.A.; Casau, M.; Santos, A.; Caramelo, F.; Falacho, R.I.; Santos, J.M. Evaluation of Root-End Preparation with Two Different Endodontic Microsurgery Ultrasonic Tips. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Arslan, H. Effectiveness of the Static-Guided Endodontic Technique for Accessing the Root Canal through MTA and Its Effect on Fracture Strength. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 1989–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, C.; Sayeh, A.; Etienne, O.; Gros, C.I.; Mark, A.; Couvrechel, C.; Meyer, F. Microguided Endodontics: Accuracy Evaluation for Access through Intraroot Fibre-post. Aust. Endodon. J. 2021, 47, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, C.; Finelle, G.; Couvrechel, C. Optimisation of a Guided Endodontics Protocol for Removal of Fibre-reinforced Posts. Aust. Endodon. J. 2020, 46, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, L.M.; Toubes, K.M.; Moreira, G., Jr.; Tonelli, S.Q.; de Machado, V.C.; Silveira, F.F.; Nunes, E. Guided Endodontics in Nonsurgical Retreatment of a Mandibular First Molar: A New Approach and Case Report. Iran Endod. J. 2020, 15, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, L.M.; Bambirra Júnior, W.; Toubes, K.M.; Moreira Júnior, G.; de Carvalho Machado, V.; Parpinelli, B.C.; Ribeiro Sobrinho, A.P. Endodontic Guide for the Conservative Removal of a Fiber-Reinforced Composite Resin Post. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, L.M.; de Carvalho Machado, V.; da Silva, N.R.F.A.; Brito Júnior, M.; da Silveira, R.R.; Moreira Júnior, G.; Ribeiro Sobrinho, A.P. Case Reports in Maxillary Posterior Teeth by Guided Endodontic Access. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, M.C.; Altoe, M.M.; de Azevedo Mohamed, C.P.; de Oliveira, L.A.; Salles, L.P. Guided Endodontic Treatment in a Region of Limited Mouth Opening: A Case Report of Mandibular Molar Mesial Root Canals with Dystrophic Calcification. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.M.; Diogo, P.; Dias, S.; Marques, J.A.; Palma, P.J.; Ramos, J.C. Long-Term Outcome of Nonvital Immature Permanent Teeth Treated with Apexification and Corono-Radicular Adhesive Restoration–a Case Series. J. Endod. 2022, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, W.L.F.; de Machado, V.C.; Fonseca, F.O.; Vasconcellos, B.C.; Guimarães, L.C.; Viana, A.C.D.; Henriques, L.C.F. Guided Endodontics in Complex Scenarios of Calcified Molars. Iran Endod. J. 2020, 15, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Jain, P.K.; Kankar, P.K. Progress and Issues Related to Designing and 3D Printing of Endodontic Guide. In Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 331–337. ISBN 9789811327186. [Google Scholar]

- Buchgreitz, J.; Buchgreitz, M.; Mortensen, D.; Bjørndal, L. Guided Access Cavity Preparation Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography and Optical Surface Scans-an Ex Vivo Study. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llaquet Pujol, M.; Vidal, C.; Mercadé, M.; Muñoz, M.; Ortolani-Seltenerich, S. Guided Endodontics for Managing Severely Calcified Canals. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Jeon, W.S.; Cho, J.M.; Jeong, H.; Shin, Y.; Park, W. Access Opening Guide Produced Using a 3D Printer (AOG-3DP) as an Effective Tool in Difficult Cases for Dental Students. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.A.Z.; Elias, M.R.A.; Capeletti, L.R.; Silva, J.A.; Siqueira, P.C.; Chaves, G.S.; Decurcio, D.A. Guided Endodontics: Volume of Dental Tissue Removed by Guided Access Cavity Preparation—An Ex Vivo Study. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostunov, J.; Rammelsberg, P.; Klotz, A.-L.; Zenthöfer, A.; Schwindling, F.S. Minimization of Tooth Substance Removal in Normally Calcified Teeth Using Guided Endodontics: An In Vitro Pilot Study. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hong, T.; Bai, S.; Tian, Y. The Effects of Endodontic Access Cavity Design on Dentine Removal and Effectiveness of Canal Instrumentation in Maxillary Molars. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 2290–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S. Clinical Practical Guidelines On Minimally Invasive Endodontics. Int. J. Dent. Oral Sci. 2021, 8, 3601–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrique Barbosa Ribeiro, F.; das Graças Oliveira Maia, B.; Silvestre Verner, F.; Binato Junqueira, R. Aspectos Atuais Da Endodontia Guiada. HU Rev. 2020, 46, 29153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Jain, P.K.; Kankar, P.K.; Jain, N. Computer-Aided Design–Based Guided Endodontic: A Novel Approach for Root Canal Access Cavity Preparation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H. 2018, 232, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connert, T.; Zehnder, M.S.; Weiger, R.; Kühl, S.; Krastl, G. Microguided Endodontics: Accuracy of a Miniaturized Technique for Apically Extended Access Cavity Preparation in Anterior Teeth. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, R.; Volland, J.; Reich, S.; Soliman, S.; Connert, T.; Krastl, G. Guided Endodontic Treatment of Multiple Teeth with Dentin Dysplasia: A Case Report. Head Face Med. 2020, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connert, T.; Krug, R.; Eggmann, F.; Emsermann, I.; ElAyouti, A.; Weiger, R.; Kühl, S.; Krastl, G. Guided Endodontics versus Conventional Access Cavity Preparation: A Comparative Study on Substance Loss Using 3-Dimensional–Printed Teeth. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, A.; Boelen, G.; Lambrechts, P.; Pedano, M.S.; Jacobs, R. Dynamic Navigation: A Laboratory Study on the Accuracy and Potential Use of Guided Root Canal Treatment. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connert, T.; Leontiev, W.; Dagassan-Berndt, D.; Kühl, S.; ElAyouti, A.; Krug, R.; Krastl, G.; Weiger, R. Real-Time Guided Endodontics with a Miniaturized Dynamic Navigation System Versus Conventional Freehand Endodontic Access Cavity Preparation: Substance Loss and Procedure Time. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarini, G.; Galli, M.; Morese, A.; Stefanelli, L.V.; Abduljabbar, F.; Giovarruscio, M.; di Nardo, D.; Seracchiani, M.; Testarelli, L. Precision of Dynamic Navigation to Perform Endodontic Ultraconservative Access Cavities: A Preliminary In Vitro Analysis. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1286–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.D.; Saunders, M.W.; Carrico, C.K.; Jadhav, A.; Deeb, J.G.; Myers, G.L. Dynamically Navigated versus Freehand Access Cavity Preparation: A Comparative Study on Substance Loss Using Simulated Calcified Canals. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1745–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianat, O.; Nosrat, A.; Tordik, P.A.; Aldahmash, S.A.; Romberg, E.; Price, J.B.; Mostoufi, B. Accuracy and Efficiency of a Dynamic Navigation System for Locating Calcified Canals. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1719–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janabi, A.; Tordik, P.A.; Griffin, I.L.; Mostoufi, B.; Price, J.B.; Chand, P.; Martinho, F.C. Accuracy and Efficiency of 3-Dimensional Dynamic Navigation System for Removal of Fiber Post from Root Canal–Treated Teeth. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta-Macho, Á.; de Pedro Muñoz, A.; Riad Deglow, E.; Agustín-Panadero, R.; Mena Álvarez, J. Accuracy of Computer-Aided Dynamic Navigation Compared to Computer-Aided Static Procedure for Endodontic Access Cavities: An In Vitro Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, L.M.; Moreira Júnior, G.; de Albuquerque, R.C.; de Carvalho Machado, V.; da Silva, N.R.F.A.; Hauss, D.D.; da Silveira, R.R. Three-Dimensional Endodontic Guide for Adhesive Fiber Post Removal: A Dental Technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Álvarez, J.; Rico-Romano, C.; Lobo-Galindo, A.B.; Zubizarreta-Macho, Á. Endodontic Treatment of Dens Evaginatus by Performing a Splint Guided Access Cavity. J. Esthetic Restorat. Dent. 2017, 29, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Venkatesh, K.V.; Sihivahanan, D. Microguided Endodontics: A Case Report of Conservative Approach for the Management of Calcified Maxillary Lateral Incisors. Saudi Endod. J. 2021, 11, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Mendes, S.T.O.; de Barbosa, C.F.M.; Machado, V.C.; Santa-Rosa, C.C. A New Approach for Minimally Invasive Access to Severely Calcified Anterior Teeth Using the Guided Endodontics Technique. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 1578–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.A.Z.; Silva, J.A.; Chaves, G.S.; Capeletti, L.R.; Estrela, C.; Decurcio, D.A. Guided Endodontics: The Impact of New Technologies on Complex Case Solution. Aust. Endod. J. 2021, 47, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krastl, G.; Zehnder, M.S.; Connert, T.; Weiger, R.; Kühl, S. Guided Endodontics: A Novel Treatment Approach for Teeth with Pulp Canal Calcification and Apical Pathology. Dent. Traumatol. 2016, 32, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.; Tawani, G.; Warhadpande, M.; Raut, A.; Dakshindas, D.; Wankhade, S. Guided Endodontic Therapy: Management of Pulp Canal Obliteration in the Maxillary Central Incisor. J. Conserv. Dent. 2019, 22, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, W.J.; Vissink, A.; Ng, Y.L.; Gulabivala, K. 3D Computer Aided Treatment Planning in Endodontics. J. Dent. 2016, 45, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Shaheen, E.; Lambrechts, P.; Politis, C.; Jacobs, R. Microguided Endodontics: A Case Report of a Maxillary Lateral Incisor with Pulp Canal Obliteration and Apical Periodontitis. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Lerut, K.; Lambrechts, P.; Jacobs, R. Guided Endodontics: Use of a Sleeveless Guide System on an Upper Premolar with Pulp Canal Obliteration and Apical Periodontitis. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchgreitz, J.; Buchgreitz, M.; Bjørndal, L. Guided Endodontics Modified for Treating Molars by Using an Intracoronal Guide Technique. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lara-Mendes, S.T.O.; de Barbosa, C.F.M.; Santa-Rosa, C.C.; Machado, V.C. Guided Endodontic Access in Maxillary Molars Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography and Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing System: A Case Report. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connert, T.; Zehnder, M.S.; Amato, M.; Weiger, R.; Kühl, S.; Krastl, G. Microguided Endodontics: A Method to Achieve Minimally Invasive Access Cavity Preparation and Root Canal Location in Mandibular Incisors Using a Novel Computer-Guided Technique. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordone, A.; Couvrechel, C. Treatment of Obliterated Root Canals Using Various Guided Endodontic Techniques: A Case Series. G Ital. Endod. 2020, 34, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, A.; Elsewify, T.; Hassanien, E. Endodontic Guides and Ultrasonic Tips for Management of Calcifications. G Ital. Endod. 2021, 35, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Chong, B.S. 3D Imaging, 3D Printing and 3D Virtual Planning in Endodontics. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rabié, C.; Torres, A.; Lambrechts, P.; Jacobs, R. Clinical Applications, Accuracy and Limitations of Guided Endodontics: A Systematic Review. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Study Type | Aim | Sample | Included Groups | Computer-Aided Technique | Results | Main Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krug et al. (2020) [5] | In vitro | To compare the accuracy and effort of digital workflow for GEA procedures using two different software applications in 3D-printed teeth modeled to simulate PCO in vitro. | 32 3D-printed teeth with simulated PCO | Incisors | SN | Root canal location rate: SE–100%; CDX–93.8% Angle deviation (p < 0.001): CDX-1.57 (1.16–1.97)° SE–0.68 (0.47–0.90)° Labial-oral deviation (p < 0.001): CDX–0.54 (0.37–0.71) mm SE–0.12 (0.06–0.18) mm Mesiodistal and Coronal-apical deviation (p > 0.05): no statistically significant difference 3D vector deviation (p < 0.001): CDX–0.74 (0.60–0.87) mm SE–0.35 (0.26–0.43) mm Planning time (p < 0.05): CDX–10 min 50 s (4 min 16 s–17 min 24 s) SE–20 min 28 s (11 min 2 s–29 min 54 s) Number of computer clicks (p < 0.01): CDX–107 (62–151) SE–341 (208–473) | Both methods enabled rapid drill path planning, a predictable GEA procedure, and the reliable location of root canals in teeth with PCO without perforation. |

| Leontiev et al. (2021) [22] | In vitro | To demonstrate that MRI is sufficiently accurate for the detection of root canals using guided endodontics. | 100 human teeth | Anterior and premolar | SN | Root canal location rate: 91% Angle deviation: 1.82 (0.00–7.60)° Bur‘s base deviation: 0.21–0.31 mm Bur‘s tip deviation: 0.28–0.44 mm Preparation in the buccolingual dimension was significantly more precise in mandibular compared with maxillary teeth, and accuracy in the mesiodistal dimension was more precise in anterior teeth compared with premolars. | This in vitro study demonstrated the suitability of MRI for guided endodontic access cavity preparation. |

| Perez et al. (2021) [27] | In vitro | To evaluate accuracy of surgically guided endodontics when applied to the endodontic retreatment of canals with fibre-posts. | 40 human teeth | Molars and bicuspids | SN | Apical gutta-percha location rate: 87.5% Coronal stage deviation (n = 40): Buccal-oral–0.23 ± 0.18 mm Mesial-distal–0.28 ± 0.12 mm Global–0.39 ± 0.14 mm Apical stage deviation (n = 35): Buccal-oral–0.24 ± 0.20 mm Mesial-distal–0.26 ± 0.15 mm Global–0.40 ± 0.19 mm Difference between operators: Not found | Microguided endodontics is a predictable and accurate method to remove fibre-post restorations efficiently. |

| Nayak et al. (2018) [43] | In vitro | Not mentioned | 6 human teeth | Single-rooted human teeth (incisors, laterals, canines, and premolars) | SN | Maximum deviation found: 0.210 ± 0.04 mm ∆X = 0.134 ± 0.03 mm ∆Y = 0.145 ± 0.05 mm ∆D = 0.210 ± 0.04 mm ∆E = 0.07 ± 0.02 mm | The proposed method reveals encouraging results for endodontic guide design. |

| Conner et al. (2017) [44] | In vitro | To assess the accuracy of guided endodontics in mandibular anterior teeth by using miniaturized instruments. | 60 human teeth | Mandibular incisors and canines | SN | Total time required: 613 (447–936) s Deviation Angle: 1.59 (0–5.3)° Bur’s base deviation: Mesial-distal–0.12 (0–0.54) mm Buccal-oral–0.13 (0–0.4) mm Apical-coronal–0.12 (0–0.41) mm Bur’s tip deviation: Mesial-distal–0.14 (0–0.99) mm Buccal-oral–0.34 (0–1.26) mm Apical-coronal–0.12 (0–0.4) mm Difference between operators: Not found | Microguided endodontics provides an accurate, fast, and operator-independent technique for the preparation of apically extended access cavities in teeth with narrow roots such as mandibular incisors. |

| Zehnder et al. (2016) [1] | Ex vivo | To present a novel method utilizing 3D printed templates to gain guided access to root canals and to evaluate its accuracy in vitro. | 60 human teeth | Incisors, laterals, canines and premolars (single-rooted human teeth) | SN | Root canal location rate: 100% Angle deviation: 1.81 (0–5.6)° Bur‘s base deviation: Apical/coronal–0.16 (0–0.76) mm Mesial/distal–0.21 (0–0.75) mm Buccal/oral–0.2 (0–0.76) mm Means of deviations at bur’s base: 0.16–0.21 mm Bur‘s tip deviation: Apical/coronal–0.17 (0–0.75) mm Mesial/distal–0.29 (0–1.34) mm Buccal/oral–0.47 (0–1.59) mm Means of deviations at bur’s tip: 0.17–0.47 mm Difference between operators: Not found | ‘Guided Endodontics’ allowed an accurate access cavity preparation up to the apical third of the root utilizing printed templates for guidance. All root canals were accessible after preparation. |

| Buchgreitz et al. (2016) [35] | Ex vivo | To evaluate ex vivo, the accuracy of a preparation procedure planned for teeth with PCO using a guide rail concept based on a CBCT scan merged with an optical surface scan. | 48 human teeth | Not mentioned | SN | Root canal location rate: 79.2% Apical horizontal deviation (p < 0.001): 0.46 (0.69–0.32) mm | The combined use of CBCT and optical scans for the precise construction of a guide rail led to a drill path with a precision below a risk threshold. The present technique may be a valuable tool for the negotiation of partial or complete pulp canal obliteration. |

| Krug et al. (2020) [45] | In vitro | To compare the accuracy and effort of digital workflow for GEA procedures using two different software applications in 3D-printed teeth modeled to simulate PCO in vitro. | 32 3D-printed teeth with simulated PCO | Incisors | SN | Root canal location rate: SE–100% CDX–93.8% Angle deviation (p < 0.001): CDX–1.57 (1.16–1.97)° SE–0.68 (0.47–0.90)° Labial-oral deviation (p < 0.001): CDX–0.54 (0.37–0.71) mm SE–0.12 (0.06–0.18) mm Mesiodistal and Coronal-apical deviation (p > 0.05): no statistically significant difference 3D vector deviation (p < 0.001): CDX–0.74 (0.60–0.87) mm SE–0.35 (0.26–0.43) mm Planning time (p < 0.05): CDX–10 min 50 s (4 min 16 s–17 min 24 s) SE–20 min 28 s (11 min 2 s–29 min 54 s) Number of computer clicks (p < 0.01): CDX–107 (62–151) SE–341 (208–473) | Both methods enabled rapid drill path planning, a predictable GEA procedure, and the reliable location of root canals in teeth with PCO without perforation. |

| Ali et al. (2021) [25] | In vitro | To evaluate the effectiveness of the SN technique for accessing the root canal through the mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) and to evaluate the effect of this technique on the fracture strength of teeth. | 30 human teeth | Mandibular premolars | SN versus FH | Root canal location rate: 100% Number of cases with mishaps (p < 0.05): FH–13 SN–0 Root canals penetration time (p < 0.05): SN < FH Fracture strength (p < 0.05): FH–472.3 Newtons SN–1379.8 Newtons Non-restorable failure (p < 0.05): FH–13 SN–3 | Within the limitations of the present study, the SN technique yielded favorable results with respect to time, mishaps, and fracture strength. |

| Choi et al. (2021) [37] | In vitro | To determine the effectiveness of using an access opening guide in teaching ideal access opening shape and preventing excessive tooth loss, with a focus on predoctoral dental students. | 90 human teeth | 60 premolars and 30 molars | SN versus FH | Access opening times–premolar group: FH–327.2 ± 135.5 s SN–97.4 ± 106.6 s Access opening times–molar group: FH–547.43 ± 269.6 s SN–104.57 ± 55.5 s Volume differences–premolar group: FH–38.1 ± 32.2 mm3 SN–−2.0 ± 14.4 mm3 Volume differences–molar group: FH–72.2 ± 60.6 mm3 SN–−8.7 ± 16.8 mm3 | Using the AOG-3DP (3D printer) significantly reduced the access opening time for premolars and molars. However, there is a limitation in that CBCT DICOM images must be converted to stereolithographic. stl files in order to be printed via 3D technology. This requires additional preclinical treatment time for imaging and subsequent printing. It could be considered that this can be a useful method in difficult cases. |

| Kostunov et al. (2021) [39] | In vitro | To investigate how much tooth substance can be preserved by using the guided approach. | 30 acrylic typodont teeth | Incisors (10), premolars (10), molars (10), | SN versus FH | Root canal location rate: SN–93.3% FH–100% Tooth substance removal (FH): Incisors–16.1 ± 3.7 mm3 Premolars–44.2 ± 8.9 mm3 Molars–99.3 ± 3.1 mm3 Tooth substance removal (SN): Incisors–10.3 ± 1.1 mm3 Premolars–29.3 ± 4.2 mm3 Molars–51.8 ± 5.3 mm3 mm3 Tooth substance removal (FH vs. SN): p < 0.05 | Use of guided endodontics in normally calcified teeth enables preservation of a significant amount of tooth substance. This advantage must be carefully balanced against a greater radiation burden and risk of perforation, higher costs, and more difficult debridement and visualization of the pulp chamber and root canals. |

| Connert et al. (2019) [46] | In vitro | To compare endodontic access cavities in teeth with calcified root canals prepared with the conventional technique and a guided endodontics approach regarding the detection of root canals, substance loss, and treatment duration. | 48 3D-printed teeth with simulated calcified root canals | Upper and lower incisors | SN versus FH | Root canal location rate: FH–41.7% SN–91.7% Substance loss: FH–49.9 (42.2–57.6) mm3 SN–9.8 (6.8–12.9) mm3 Treatment duration: FH–21.8 (15.9–27.7 min) SN–11.3 (6.7–15.9 min) Operator experience: does not influenced the success of the guided approach | Guided endodontics allows a more predictable and expeditious location and negotiation of calcified root canals with significantly less substance loss. |

| Loureiro et al. (2020) [38] | Ex vivo | To compare the volume of dental tissue removed after GEA and CEA to mandibular incisors and upper molars. | 40 human teeth | 20 mandibular incisors (G1) and 20 upper molars (G2) | SN versus FH | Volume of dental tissue removed (p = 0.004): G1 group using CEA–31.667 mm3 (10.62%) G1 group using GEA–26.523 mm3 (10.65%) G2 group using CEA–62.526 mm3 (5.86%) G2 group using GEA–45.677 mm3 (4.11%) | GEA preserved a greater volume of dental tissue in extracted upper human molars than CEA; however, there was no significant difference between CEA and GEA in the volume of dental tissue removed from mandibular incisors. |

| Wang et al. (2021) [40] | In vitro | To evaluate in a laboratory setting, the impact of three designs of endodontic access cavities on dentine removal and effectiveness of canal instrumentation in extracted maxillary first molars using micro-CT. | 30 human teeth | Maxillary first molars | SN (GEC) versus TEC versus CEC | Total volume of dentin removed: TEC–81.78 ± 14.77 mm3 CEC–39.26 ± 8.99 mm3 GEC–42.39 ± 8.17 mm3 TEC group > CEC and GEC group (p < 0.05). The volume of dentine removed in the crown, pericervical dentine and coronal third of the canal was significantly lower in CEC and GEC groups when compared to that in the TEC group (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in noninstrumented canal area, canal transportation and centring ratio amongst the TEC, CEC and GEC groups (p > 0.05). | CEC and GEC preserved more tooth tissue in the crown, pericervical dentine and coronal third of the canal compared with TEC after root canal preparation. The design of the endodontic access cavity did not impact on the effectiveness of canal instrumentation in terms of noninstrumented canal area, canal transportation and centring ratio. |

| Torres et al. (2021) [47] | In vitro | To evaluate 3D accuracy and outcome of a dynamic navigation method for guided root canal treatment of severe PCO in 3D printed jaws. | 132 3D printed teeth with PCO | Anterior teeth, premolars, and molars | DN | Root canal location rate: 92.9% Mean deviation at the apical point: 0.63 mm ± 0.35 p < 0.05: anterior teeth < molars Mean angular deviation: 2.81° ± 1.53 | DN was an accurate approach for root canal treatment in teeth with severely calcified canals. However, the technique has a learning curve and requires extensive training prior to its use clinically. |

| Chong et al. (2019) [16] | In vitro | To investigate the use of DN for guided endodontics. | 29 human teeth | Incisors, laterals, canines, premolars and molars | DN | Root canal location rate: 89.1% | The results of this study demonstrate the potential of using DN technology in guided endodontics in clinical practice. |

| Jain et al. (2020) [10] | In vitro | To present a novel dynamic navigation method to attain minimally invasive access cavity preparations and to evaluate its 3D accuracy in locating highly difficult simulated calcified canals among maxillary and mandibular teeth. | 84 printed teeth with simulated PCO | Anterior, premolars and molars | DN | 2D horizontal deviation–canal orifice: 0.9 ± 0.69 mm (p < 0.05): Maxilla: 1.0 ± 0.78 mm Mandible: 1.0 ± 0.60 mm 3D deviation–canal orifice: 1.3 ± 0.65 mm (p ≥ 0.05): Maxilla: 1.2 ± 0.57 mm Mandible: 1.4 ± 0.70 mm 3D angular deviation: 1.7 ± 0.98° (p < 0.05): Premolars: 1.4 ± 0.62° Molars: 1.9 ± 1.14° The 3D and 2D discrepancies were independent of the canal orifice depths (p > 0.05). The average drilling time was 57.8 s with significant dependence on the canal orifice depth, tooth type, and jaw (p < 0.05) | This study shows the potential of applying DN technology with high-speed drills to preserve tooth structure and accurately locate root canals in teeth with pulp canal obliteration. |

| Pirani et al. (2020) [19] | In vitro | To evaluate the potential application of dynamic navigation in teaching undergraduate students the opening of the access cavity. | 3 human teeth | 2 lower molars and 1 lower premolar | DN | Root canal location rate: 100% | Present results demonstrated a possible application of this technology for educational purposes in finding root canals. |

| Connert et al. (2021) [48] | In vitro | To evaluate substance loss and the time required for ACP using the FH method versus a DN system of real-time guided endodontics in an in vitro model using 3D printed teeth. | 72 3D-printed teeth | Maxillary central incisors, lateral incisors, and canines | DN versus FH | Root canal location rate: 97.2% Substance loss (p < 0.001): FH–29.7 (24.2–35.2) mm3 DN–10.5 (7.6–13.3) mm3 Time required for ACP (p > 0.05): FH–193 (164–222) s DN–195 (135–254) s Operator experience: More experienced operator removed significantly (p < 0.001) less tooth structure (19.9 mm3) than the second operator (39.4 mm3) when performing FH. | DN is a practicable, substance-sparing method performed in comparable time as FH. Moreover, DN seems to be independent of operator experience. |

| Gambarini et al. (2020) [49] | In vitro | To evaluate the possible use of a novel DN in planning and executing ultra conservative access cavities, and its precision in vitro, compared to a FH approach without any guide. | 20 artificial teeth replicas | Upper right first molars | DN versus FH | Root canal location rate: 100% for FH and DN groups Deviation Angle (p < 0.05): FH–19.2 ± 8.6° DN–4.8 ± 1.8° Maximum distance from the ideal position (p < 0.05): FH–0.88 ± 0.41 mm DN–0.34 ± 0.19 mm Instrumentation time (p > 0.05): FH–12.2 ± 3.2 s DN–11.5 ± 2.4 s | The use of DN increased the benefits of ultra-conservative access cavities, by minimizing the potential risk of iatrogenic weakening of critical portions of the crown and reducing negative influences to shaping procedures. |

| Jain et al. (2020) [50] | In vitro | To compare the speed, qualitative precision, and quantitative loss of tooth structure with FH and DN access preparation techniques for root canal location in 3D–printed teeth with simulated calcified root canals. | 40 3D- printed teeth to simulate canal calcification | Maxillary (21) and mandibular (41) single-rooted central incisors | DN versus FH | Quantitative Substance Loss (p = 0.0356): FH–40.7 (29.1–52.2) mm3 DN–27.2 (22.0–32.5) mm3 Qualitative Precision (optimal) (p > 0.05): FH–45% DN–75% Qualitative Precision (suboptimal): FH–40% DN–15% Qualitative Precision (unacceptable): FH–15% DN–10% Treatment duration (p < 0.05): FH–424.8 (289.4–560.2) s DN–136.1 (101.4–170.8) s | Overall, DN access preparations led to significantly less substance loss with optimal and efficient precision in locating simulated anterior calcified root canals in comparison with freehand access preparations. |

| Dianat et al. (2020) [51] | Ex vivo | To compare the accuracy and efficiency of a DN system to the FH method for locating calcified canals in human teeth. | 60 human teeth with PCO | Single-rooted teeth (maxillary and mandibular incisors, canines, and premolars) | DN versus FH | Root canal location rate (p > 0.05): FH–83.3% DN–96.7% Linear deviation (BL; p ≤ 0.001): FH–0.81 ± 0.74 mm DN–0.19 ± 0.21 mm Linear deviation (MD; p > 0.05): FH–0.31 ± 0.35 mm DN–0.12 ± 0.14 mm Angular deflection (p ≤ 0.0001): FH–7.25 ± 4.2° DN–2.39 ± 0.85° Reduced Dentin Thickness (CEJ; p ≤ 0.0001): FH–1.55 ± 0.55 mm DN–1.06 ± 0.18 mm Reduced Dentin Thickness (End drilling point; p ≤ 0.001): FH–1.47 ± 0.49 mm DN–1.18 ± 0.17 mm Time required for ACP (p ≤ 0.05) (s) FH–405 ± 246 s DN–227 ± 97 s Mishaps (p ≤ 0.05): FH–8 DN–1 Frequency of Successful Attempts (p > 0.05): FH–25/30 DN–29/30 Operator experience: The time required for ACP was significantly shorter for the board-certified endodontist in the FH group (p ≤ 0.05). The rest of the measured variables were not different between the 2 operators (p > 0.05) | The DN system was more accurate and more efficient than the FH technique in locating calcified canals in human teeth. This novel DN system can help clinicians avoid catastrophic mishaps during access preparation in calcified teeth. |

| Janabi et al. (2021) [52] | In vitro | To investigate the accuracy and efficiency of the 3D DN system compared with the FH technique when removing fiber posts from root canal–treated teeth. | 26 human teeth | Maxillary single-rooted teeth (maxillary canines and incisors) | DN versus FH | Coronal deviation (p < 0.05): FH–1.13 ± 0.84 mm DN–0.91 ± 0.65 mm Apical deviation deviation (p < 0.05): FH–1.68 ± 0.85 mm DN–1.17 ± 0.64 mm Angular deflection (p < 0.05): FH–4.49 ± 2.10° DN–1.75 ± 0.63° Operation time (p < 0.05): FH–8.30 ± 4.65 min DN–4.30 ± 0.43 mi Volumetric loss of tooth structure (p < 0.05): DN < FH | The DN system was more accurate and efficient in removing fiber posts from root canal–treated teeth than the FH technique. |

| Zubizarreta-Macho et al. (2020) [53] | In vitro | To analyze the accuracy of two computer-aided navigation techniques to guide the performance of endodontic access cavities compared with the FH procedure. | 30 human teeth | Single-rooted anterior teeth (lower central incisors)) | SN versus DN versus FH | Coronal deviation (p-value): SN-DN = 0.654 SN-FH < 0.001 DN-FH < 0.001 Apical deviation (p-value): SN-DN = 0.914 SN-FH < 0.001 DN-FH < 0.001 Angular deviation (p-value): SN-DN = 0.072 SN-FH < 0.001 DN-FH < 0.001 | SN and DN procedures allow more accurate and safe endodontic access to cavities than conventional freehand techniques. |

| Author (Year) | Study Type | Aim | Tooth | Computer-Aided Technique | Outcome | Main Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up | Clinical and/or Radiographic | ||||||

| Casadei et al. (2020) [3] | Case Report | To describe endodontic treatment where there was an intercurrence, generating deviation and perforation, which was solved with the aid of guided endodontics. | Calcified maxillary right second premolar | SN | 1 year | Clinical: Absence of painful symptoms and a negative response to clinical tests. Radiographic: Regression of the periapical lesion. | This technique proved to be safe and predictable, allowing for a favorable prognosis in the long term. |

| Zubizarreta-Macho et al. (2019) [11] | Case Report | To propose a novel technique, based on new technologies, to make access cavity conservative and guided with minimal dental structure lost. | Retreatment of a DI in a maxillary left lateral incisor | SN | 6, 12 and 18 months | Clinical: Absence of clinical signs. Radiographic: Reduction of the periapical lesion. | The splint guide allowed a guided and conservative access cavity to root canal system. It facilitates the root canal retreatment and improves the prognosis of the teeth with dental malformations. |

| Zubizarreta-Macho et al. (2015) [12] | Case Report | To describe the treatment of a type II DI by means of guided splints for cavity access. | Maxillary left lateral incisor with type II DI | SN | 6 months | Clinical: Any signs or symptoms. Radiographic: Periapical lesion disappearance. | CBCT is an effective method for obtaining information about the root canal system in teeth with DI. Guided implant surgery software is effective for manufacturing splint guides for endodontic treatment with conservative pulp chamber access. |

| Ali et al. (2019) [13] | Case Report | To describe the use of the guided endodontics technique for two maxillary lateral incisors with multiple DI. | Maxillary lateral incisors with type II DI | SN | Not mentioned | Radiographic: Regression of the periapical lesion in relation to teeth 21 and 22. | This technique can be a valuable tool for negotiation of the DI and the main root canal, reducing chair-time and, more importantly, the risk of iatrogenic damage to the tooth structure. |

| Ishak et al. (2020) [20] | Case Report | To evaluate the benefits and limitations of the micro-guided technique. | Calcified central lower incisors | SN | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | The guided approach allows predictable, efficient endodontic treatment of teeth presenting calcified canals, with minimal removal of sound dentine and less risk of root perforations. |

| Maia et al. (2019) [54] | Case Report | To describe a protocol for adhesive fiber post removal using a prototyped endodontic guide. | Maxillary right central incisor restored with a fiber post | SN | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | The CAD/CAM technology to generate guides with prototyping is a useful tool for fiber post removal. |

| Perez et al. (2020) [27] | Case Report | To demonstrate the usefulness of endodontic guides for the removal of fiber posts. | Maxillary right first molar restored with a fiber post | SN | 12 months | Radiographic: Apical area healed. | This case study illustrates the benefits of endodontic guides for the removal of fibre posts. It also demonstrates the feasibility of the technique in the posterior segment where the bulkiness of the device might appear to be a drawback. |

| Mena-Álvarez et al. (2017) [55] | Case Report | To describe the treatment of a type V dens evaginatus by using splits as guides to perform access cavity. | Maxillary left central incisor with type V dens evaginatus | SN | 1 year | Radiographic: Recovery and disappearance of the periapical lesion. | CBCT is an effective method for obtaining internal anatomical information of teeth with anatomical malformations. The osseointegrated implant planning software is an effective method for planning root canal treatment and designing stereolithograped splits (for performing minimally invasive access cavities) |

| Maia et al. (2021) [28] | Case Report | To describe the use of a prototyped guide created with virtual planning for fiber-reinforced composite resin post removal. | Maxillary left central incisor restored with a fiber post | SN | 18 months | Radiograpchic: Apical lesion healed. | The prototyped guide improved patient safety, decreased professional stress, shortened the treatment time, preserved the esthetics, and eliminated the need for a new restoration. In addition, this approach does not require specialized training or extensive clinical experience to achieve predictable results. |

| Maia et al. (2020) [28] | Case Report | To describe the use of the guided endodontics for a non-surgical endodontic retreatment of the mandibular molar. | Nonsurgical re-treatmen of a mandibular right first molar | SN | 24 months | Radiographic: Reduction of the periapical lesion, suggestive of complete healing. | The EndoGuide technique can be indicated as a fast, available and accurate solution for endodontic therapy in calcified root canals. |

| Santiago et al. (2022) [31] | Case Report | To describe the CAD/CAM workfow to create personalized templates with innovative design and the guided endodontics’ clinical procedures to treat the obliterated mesiobuccal and mesiolingual root canals of a mandibular molar. To compare the open-template design to the compact design and report the success assessment after one year of follow-up. | Mandibular right first molar with dystrophic calcifcation | SN | 1 year | Clinical: Asymptomatic tooth, negative to percussion tests. Radiographic: Integrity of the adjacent tissues. | The digital planning and guided access permitted to overcome the case limitations and then re-establish the glide path following the original anatomy of the root canals. The guided endodontic represents a personalized technique that provides security, reduced risks of root perforation, and a significant decrease of the working time to access obliterated root canals even in the mesial root canal of mandibular molars, a region of limited mouth opening. |

| Kaur et al. (2021) [56] | Case Report | To describe the use of guided endodontics in calcified maxillary lateral incisor using small diameter bur. | Calcified maxillary left lateral incisor | SN | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | This method demonstrated an ultraconservative, highly reliable, and successful treatment without the excessive removal of enamel and dentin. |

| Lara-Mendes et al. (2018) [57] | Case Report | To describe an endodontic treatment technique performed through a new minimally invasive approach that leads to no tooth damage at the incisal edge and uses CBCT imaging and 3D guides. | Calcified maxillary left central incisor | SN | 1 year | Clinical: Asymptomatic patient. Radiographic: Small alteration in the periodontal ligament space, which may be a sign of the presence of scar tissue. | The guided endodontic therapy optimized the treatment, having provided a conservative access with no tooth damage at the incisal edge in a safe and predictable way despite the presence of a severely calcified root canal. |

| Loureiro et al. (2021) [58] | Case Report | To discuss the impact of new technologies on the treatment of a complex case of a maxillary central incisor with PCO, lateral perforation and apical periodontitis treated using guided endodontics. | Calcified maxillary left central incisor | SN | 6 months | The periapical radiograph and CBCT scan showed that the guided endodontics approach was radiographically successful. | CBCT contributed effectively for the diagnosis of a perforation that occurred during failed attempts to access the root canal. Guided endodontics, a quick, safe and comfortable intervention, is also very affordable because it does not require any surgical procedures. |

| Krastl et al. (2016) [59] | Case Report | To present a new treatment approach for teeth with PCO which require root canal treatment. | Calcified maxillary right central incisor | SN | 15 months | Clinical: Asymptomatic with no pain on percussion Radiographic: No apical pathology | The presented guided endodontic approach seems to be a safe, clinically feasible method to locate root canals and prevent root perforation in teeth with PCO. |

| Hedge et al. (2019) [60] | Case Report | To report the management of PCO of maxillary central incisor using guided endodontic therapy. | Calcified maxillary right central incisor | SN | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Guided endodontic therapy was found to be a time-saving method of the management of PCO in anterior teeth. |

| van der Meer et al. (2016) [61] | Case Report | To describe the application of 3D digital mapping technology for predictable navigation of obliterated canal systems during root canal treatment to avoid iatrogenic damage of the root. | Anterior teeth/ Not mentioned | SN | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | The method of digital designing and rapid prototyping of endodontic guides allows for reliable and predictable location of root canals of teeth with calcifically metamorphosed root canal systems. |

| Torres et al. (2019) [62] | Case Report | To describe a minimally invasive method to create a 3D-printed guide to gain access to obliterated root canals on the basis of CBCT data. | Calcified maxillary left lateral incisor | SN | 6 months | Radiographic: Apical area completely healed. | Microguided Endodontics concept may be a valuable tool for the negotiation of PCO, reducing chair time and risk of iatrogenic damage to the root. |

| Torres et al. (2021) [63] | Case Report | To present a novel guided endodontics technique using a sleeveless 3D printed guide. | Calcified first maxillary right premolar | SN | 1 year | Radiographic: Apical area completely healed. | This technique seems to be a promising alternative in comparison to the conventional guided endodontic guide-design for the negotiation of PCO in cases where vertical space is limited. |

| Buchgreitz et al. (2019) [64] | Case Report | To show a modification of guided endodontics with the purpose of reducing the need for interocclusal space using an intracoronal guide technique whereby it can be applied more often in the posterior region. | Calcified first maxillary right molar | SN | 2 years | Clinical: Any objective symptoms of apical inflammation. Radiographic: Sustained lamina dura indicative of healing. | The demand for more interocclusal space was solved by transforming the virtual drill path into a composite-based intracoronal guide. |

| Lara-Mendes et al. (2018) [65] | Case report (2 treated teeth) | To describe a guided endodontic technique that facilitates access to root canals of molars presenting with pulp calcifications. | Calcified maxillary left second and third molars | SN | 3 months | Radiographic: Regression of the periradicular lesions. | The guided endodontic technique in maxillary molars was shown to be a fast, safe, and predictable therapy and can be regarded as an excellent option for the location of calcified root canals, avoiding failures in complex cases. |

| 1 year | Clinical: Reduction of pain symptoms and a negative response to the percussion tests. Radiographic: Reduction of the periradicular lesions. | ||||||

| Connert et al. (2018) [66] | Case report (2 treated teeth) | To present a novel miniaturized and minimally invasive treatment approach for root canal localization in mandibular incisors with PCO and apical periodontitis. | Calcified mandibular central incisors | SN | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | The ‘Microguided Endodontics’ technique is a safe and minimally invasive method for root canal location and prevention of technical failures in anterior teeth with PCO. |

| Krug et al. (2020) [45] | Case report (6 treated teeth) | To report the outcome of guided endodontic treatment of a case of dentin dysplasia with PCO and apical periodontitis based on the use of a 3D-printed template designed by merging CBCT and surface scan data. | Maxillary right lateral incisor, maxillary right second premolar, maxillary left first molar, mandibular left incisors and mandibular right first molar with dentin dysplasia | SN | 1 year | Clinical: Asymptomatic teeth, with mobility improvement. Radiographic: Signs of apical lesion size reduction in teeth 36, 32 and 12. Complete healing of apical periodontitis obtained in teeth 15, 26, 31 and 46. | In patients with dentin dysplasia, conventional endodontic therapy is challenging. Guided endodontic treatment considerably facilitates the root canal treatment of teeth affected by dentin dysplasia. |

| Maia et al. (2019) [30] | Case report (3 treated teeth) | To describe the endodontic treatment of 1 molar and 2 premolars with extremely calcified canals using the guided endodontics technique. | Calcified maxillary first left molar; calcified maxillary second left upper premolar; calcified maxillary second right premolar | SN | 15 days | Clinical: All the patients asymptomatic. | Although extremely detailed planning is required, the execution of the technique is relatively fast and safe, substantially reducing the occurrence of iatrogenic failures and increasing the success rates of endodontic treatment. |

| 6 months | Radiographic: Case 1 and 3–Periapical tissue mineralization. Case 2–Absence of periapical thickening. | ||||||

| 1 year | Radiographic: Case 1, 2 and 3–Complete healing | ||||||

| Bordone et al. (2020) [67] | Case series (4 clinical cases) | To demonstrate the benefits and limits of static guided endodontics. | Calcified mandibular right canine; calcified maxillary right central incisor; calcified mandibular left canine; maxillary right canine | SN | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | SN assists endodontists in the management of complex cases by enabling centered drilling of the canal with minimum risk of deviating from the virtually planned path. The novel choice of a small-diameter drill (0.75 mm) helps maximize the preservation of the dental tissues. |

| Tavares et al. (2018) [7] | Case Series (2 clinical cases) | To describe 2 cases of guided endodontics programmed with conventional palatal access in anterior teeth and to discuss the applicability of this approach in cases of PCO with apical periodontitis and acute symptoms. | Calcified maxillary right central incisor | SN | Case report 1: 15 days Case report 2: 30 days. | Clinical: Asymptomatic teeth. | The method demonstrated high reliability and permitted proper root canal disinfection expeditiously, without the unnecessary removal of enamel and dentin in the incisal surface. |

| Ali et al. (2019) [14] | Case series (2 clinical cases) | To describe the conservative endodontic treatment of a type II DI (dens Invaginatus) with guided endodontic approach and 3D printed surgical stents. | Case report 1: maxillary incisors with type II DI Case report 2: maxillary right incisors with type II DI | SN | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | This technique provides a precise and minimally invasive approach in the conservative management of DI, without compromising the vitality of main pulpal tissue. |

| Llaquet et al. (2020) [36] | Case series (7 clinical cases) | To describe the endodontic management of seven teeth with PCO by means of digitally guided endodontics using both a virtually designed 3D guide and a customized 1 mm-diameter cylindrical bur. | Calcified maxillary left central incisor (3 case reports); calcified maxillary right canine (1 case report); calcified maxillary right central incisor (3 case reports) | SN | 1 year | Clinical: No patients reported discomfort upon percussion or palpation at least one year after the treatment, when periapical healing was evident. | This treatment approach was demonstrated to be safe and fast and can be considered as a predictable technique for the location of calcified canals, thus minimizing complications. |

| Tavares et al. (2020) [33] | Case series (3 clinical cases) | To report a case series and describe the use of guided endodontics in complex symptomatic cases of mandibular and maxillary molars; presenting calcification of all three root canals. | Calcified mandibular second right molar; calcified mandibular right first molar; calcified maxillary right first molar | SN | Case report 1: 15 days; 12 months Case report 3: 1 week; 12 months | Clinical: asymptomatic teeth. | The use of guided endodontics in cases of calcification in molars was demonstrated to be a viable and reliable alternative treatment. |

| Shaban et al. (2021) [68] | Case series (2 clinical cases) | To describe the role of guided endodontics with ultrasonic tips in management of calcified canals. | Calcified maxillary left central incisor; calcified maxillary right first molar | SN | Case report 1 and 2: 2 weeks | Clinical: Asymptomatic, negative on palpation and percussion. | Endodontics guides with ultrasonic tips are reliable in management of root canal calcifications. Three-dimensional imaging using CBCT and CAD/CAM provides accurate 3D guides. |

| Case report 1 and 2: 1 year | Radiographic: Normal periapical radiographic appearance. | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, D.; Reis, E.; Marques, J.A.; Falacho, R.I.; Palma, P.J. Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques—A Literature Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12091516

Ribeiro D, Reis E, Marques JA, Falacho RI, Palma PJ. Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques—A Literature Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022; 12(9):1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12091516

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Diana, Eva Reis, Joana A. Marques, Rui I. Falacho, and Paulo J. Palma. 2022. "Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques—A Literature Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 12, no. 9: 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12091516

APA StyleRibeiro, D., Reis, E., Marques, J. A., Falacho, R. I., & Palma, P. J. (2022). Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques—A Literature Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(9), 1516. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12091516