Suction Drain Volume following Axillary Lymph Node Dissection for Melanoma—When to Remove Drains? A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Complications and Revision Surgery

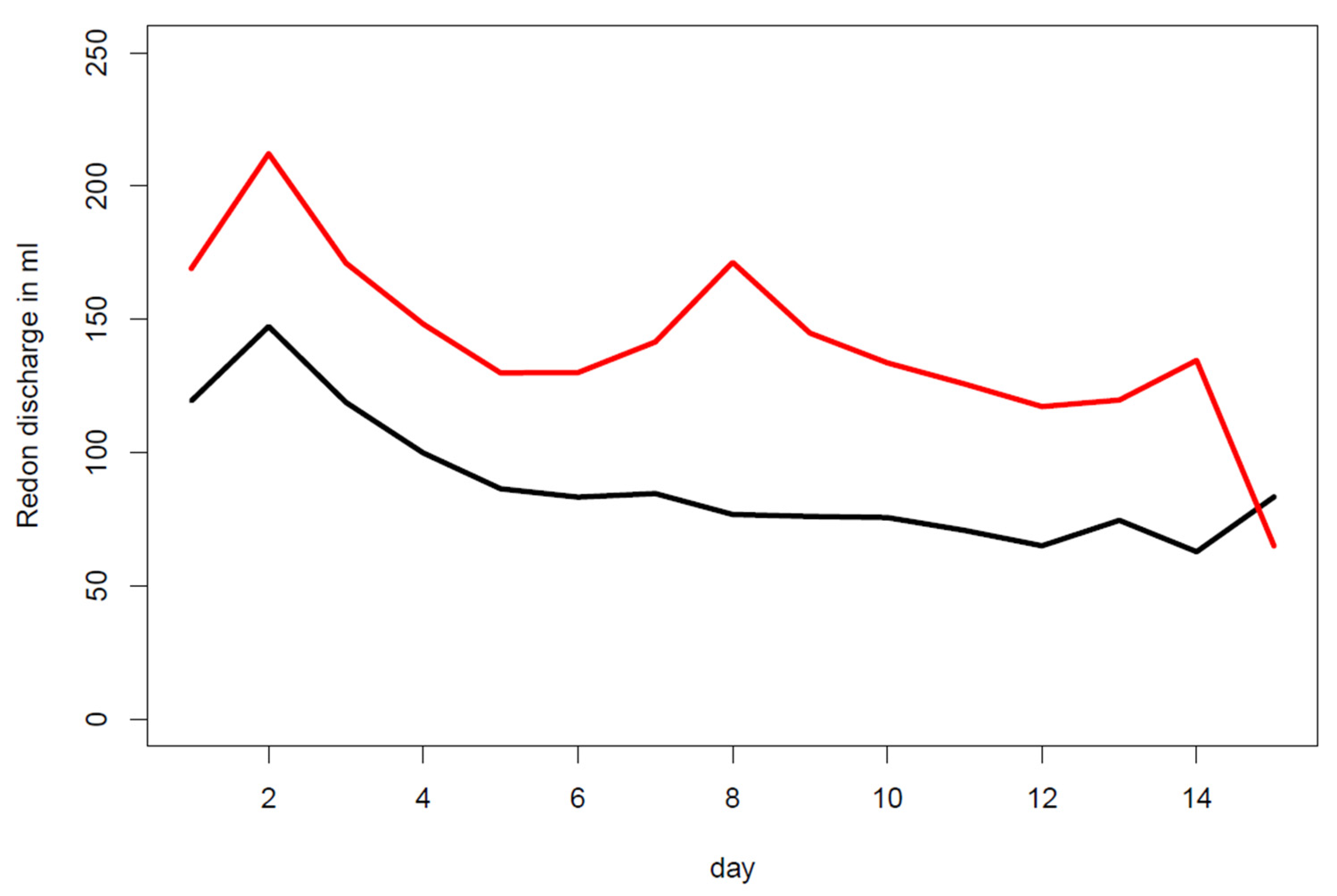

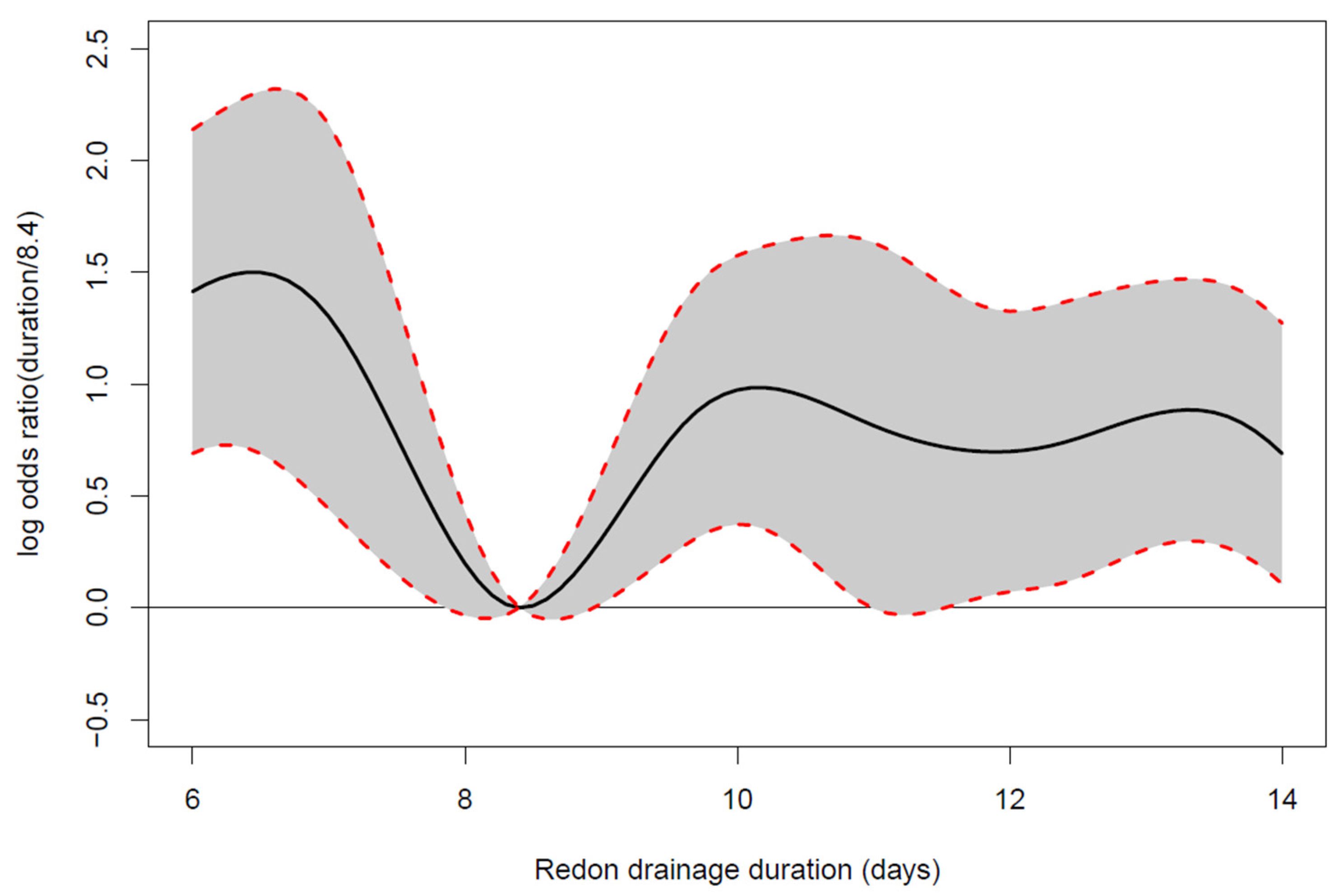

3.3. Drain Indwelling Time

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dummer, R.; Hauschild, A.; Lindenblatt, N.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Keilholz, U. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26 (Suppl. S5), v126–v132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.L.; Faries, M.B.; Kennedy, E.B.; Agarwala, S.S.; Akhurst, T.J.; Ariyan, C.; Balch, C.M.; Berman, B.S.; Cochran, A.; Delman, K.A.; et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Management of Regional Lymph Nodes in Melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 356–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, D.L.; Wanek, L.; Nizze, J.A.; Elashoff, R.M.; Wong, J.H. Improved Long-term Survival after Lymphadenectomy of Melanoma Metastatic to Regional Nodes. Analysis of prognostic factors in 1134 patients from the John Wayne Cancer Clinic. Ann. Surg. 1991, 214, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbe, C.; Amaral, T.; Peris, K.; Hauschild, A.; Arenberger, P.; Bastholt, L.; Bataille, V.; del Marmol, V.; Dréno, B.; Fargnoli, M.C.; et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 2: Treatment—Update 2019. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 126, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.L.; Thompson, J.F.; Cochran, A.J.; Mozzillo, N.; Elashoff, R.; Essner, R.; Nieweg, O.E.; Roses, D.F.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Karakousis, C.P.; et al. Sentinel-Node Biopsy or Nodal Observation in Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, J.; Botham, S.; Dahill, K.; Wallace, D.; Hardwicke, J. Complications following completion lymphadenectomy versus therapeutic lymphadenectomy for melanoma—A systematic review of the literature. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 43, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roses, D.F.; Brooks, A.D.; Harris, M.N.; Shapiro, R.L.; Mitnick, J. Complications of Level I and II Axillary Dissection in the Treatment of Carcinoma of the Breast. Ann. Surg. 1999, 230, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.D. Prevention of Seromas in Mastectomy Wounds: The effect of shoulder immobilization. Arch. Surg. 1995, 130, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R.F.; van Geel, A.N.; de Groot, H.G.; Rottier, A.B.; Olthuis, G.A.; van Putten, W.L. Immediate versus delayed shoulder exercises after axillary lymph node dissection. Am. J. Surg. 1990, 160, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hea, B.J.; Ho, M.N.; Petrek, J. External compression dressing versus standard dressing after axillary lymphadenectomy. Am. J. Surg. 1999, 177, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D.R.; Sadideen, H.; Furniss, D. Wound drainage after axillary dissection for carcinoma of the breast. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2021, CD006823. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, T.A.; Thomson, D.R.; Furniss, D. When should axillary drains be removed post axillary dissection? A systematic review of randomised control trials. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 21, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, D.R.; Trevatt, A.E.; Furniss, D. When should axillary drains be removed? A meta-analysis of time-limited versus volume controlled strategies for timing of drain removal following axillary lymphadenectomy. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2016, 69, 1614–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, R.; Abdall-Razak, A.; Crossley, E.; Dowlut, N.; Iosifidis, C.; Mathew, G.; Bashashati, M.; Millham, F.H.; Orgill, D.P.; Noureldin, A.; et al. STROCSS 2019 Guideline: Strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2019, 72, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.-A. Classification of Surgical Complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; de Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; de Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo Classification of Surgical Complications: Five-year experience. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Namm, J.P.; Chang, A.E.; Cimmino, V.M.; Rees, R.S.; Johnson, T.M.; Sabel, M.S. Is a level III dissection necessary for a positive sentinel lymph node in melanoma? J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 105, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, L.; Thoms, K.-M.; Peeters, S.; Haenssle, H.; Bertsch, H.-P.; Emmert, S. Postoperative morbidity of lymph node excision for cutaneous melanoma-sentinel lymphonodectomy versus complete regional lymph node dissection. Melanoma Res. 2008, 18, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.; Haug, I.; Lebo, P.; Grohmann, M.; Reischies, F.M.; Cambiaso-Daniel, J.; Tuca, A.; Rienmüller, T.; Friedl, H.; Spendel, S.; et al. Standardizing the complication rate after breast reduction using the Clavien-Dindo classification. Surgery 2017, 161, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Mulk, J.; Hölmich, L.R. Lymph node dissection in patients with malignant melanoma is associated with high risk of morbidity. Dan. Med. J. 2012, 59, A4441. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V.; Basu, S.; Shukla, V.K. Seroma Formation after Breast Cancer Surgery: What We Have Learned in the Last Two Decades. J. Breast Cancer 2012, 15, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soon, P.; Clark, J.; Magarey, C. Seroma formation after axillary lymphadenectomy with and without the use of drains. Breast 2005, 14, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.C.; Rai, S.; Hoar, F.; Brown, H.; Vishwanath, L. Breast cancer surgery without suction drainage: The impact of adopting a ‘no drains’ policy on symptomatic seroma formation rates. EJSO 2013, 39, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas-Junior, R.; Ribeiro, L.F.J.; Moreira, M.A.R.; Queiroz, G.S.; Esperidião, M.D.; Silva, M.A.C.; Pereira, R.J.; Zampronha, R.A.C.; Rahal, R.M.S.; Soares, L.R.; et al. Complete axillary dissection without drainage for the surgical treatment of breast cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Clinics 2017, 72, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faries, M.B.; Thompson, J.F.; Cochran, A.J.; Andtbacka, R.H.; Mozzillo, N.; Zager, J.S.; Jahkola, T.; Bowles, T.L.; Testori, A.; Beitsch, P.D.; et al. Completion Dissection or Observation for Sentinel-Node Metastasis in Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2211–2222. Available online: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1613210%0Apapers3://publication/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1613210 (accessed on 31 October 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Complications (Clavien–Dindo Classification) | Count (Overall) | Percentage (Complication) | Percentage (Overall) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complication | 66 (118) | 100% | 55.9% |

| Grade I | 46 (66) | 69.7% | 39% |

| Grade II | 12 (66) | 18.2% | 10.2% |

| Grade IIIa | 1 (66) | 1.5% | 0.8% |

| Grade IIIb | 7 (66) | 10.6% | 5.9% |

| Grade IVa | 0 | 0% | 0% |

| Grade IVb | 0 | 0% | 0% |

| Grade V | 0 | 0% | 0% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winter, R.; Tuca, A.; Wurzer, P.; Schaunig, C.; Sawetz, I.; Holzer-Geissler, J.C.J.; Gmainer, D.G.; Luze, H.; Friedl, H.; Richtig, E.; et al. Suction Drain Volume following Axillary Lymph Node Dissection for Melanoma—When to Remove Drains? A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12111862

Winter R, Tuca A, Wurzer P, Schaunig C, Sawetz I, Holzer-Geissler JCJ, Gmainer DG, Luze H, Friedl H, Richtig E, et al. Suction Drain Volume following Axillary Lymph Node Dissection for Melanoma—When to Remove Drains? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022; 12(11):1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12111862

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinter, Raimund, Alexandru Tuca, Paul Wurzer, Caroline Schaunig, Isabelle Sawetz, Judith C. J. Holzer-Geissler, Daniel Georg Gmainer, Hanna Luze, Herwig Friedl, Erika Richtig, and et al. 2022. "Suction Drain Volume following Axillary Lymph Node Dissection for Melanoma—When to Remove Drains? A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 12, no. 11: 1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12111862

APA StyleWinter, R., Tuca, A., Wurzer, P., Schaunig, C., Sawetz, I., Holzer-Geissler, J. C. J., Gmainer, D. G., Luze, H., Friedl, H., Richtig, E., Kamolz, L.-P., & Lumenta, D. B. (2022). Suction Drain Volume following Axillary Lymph Node Dissection for Melanoma—When to Remove Drains? A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(11), 1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12111862