A Focus Group Study of Perceptions of Genetic Risk Disclosure in Members of the Public in Sweden: “I’ll Phone the Five Closest Ones, but What Happens to the Other Ten?”

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Selection

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

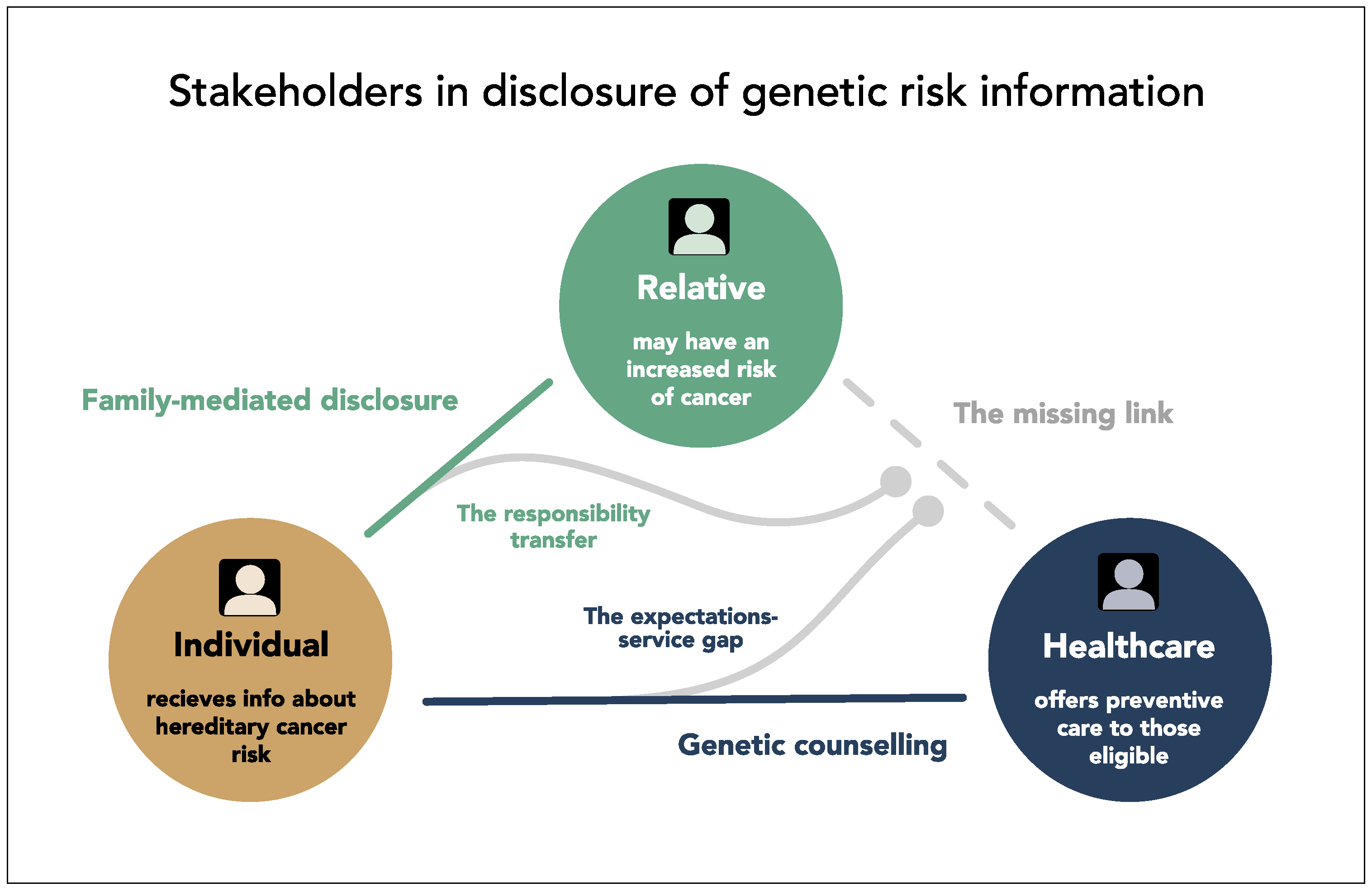

3.1. Overall Theme: A Maze of Challenges in a Haze of Silent Expectations

3.2. Theme: Face an Important but Difficult Challenge

3.2.1. Struggling with Unpleasant Feelings and Consequences

“I’m thinking it would be a terrible responsibility for the one who is 23 and in charge of informing the entire family”…(K1, FGD1)

“I think it is obvious. One cannot walk around and keep it inside because they need to get their check-ups too—they must get checked.”(M2, FGD4)

3.2.2. Allowing Type of Relationship to Govern Preferences

“Closest ones I could also call, that’s fine, to talk to by myself, or when we get together. I don’t know, but it may feel really difficult to call…well like auntie whom I haven’t seen or talked to for 20 years”…(K1, FGD3)

“…say you are my sister, and I call you to tell this, but then you ask me follow-up questions and I’m not educated to answer or calm her. Or…to explain what will come of this, how big is the chance…well, that’s it really, if you would tell me, then I would have follow-up questions and then I think my sister would be very fazed, and she’s not educated to handle if I become shocked…”(K1, FGD2)

3.2.3. Feeling That Risk Disclosure Requires Skill and Experience

“No, but I think such information is best conveyed by knowledgeable staff; there is a risk that something is distorted or misinterpreted if it should go through someone…”(M1, FGD 5)

3.3. Theme: Expect Healthcare to Lead but Also Support Disclosure

3.3.1. Depending on Healthcare to Take Main Responsibility

“It (family-mediated disclosure) is a good complement, of course one should talk about it, but at the same time information should be disclosed by healthcare too…because there one can only encourage the person to talk about it, while if healthcare manages disclosure, it will reach them…”(K2, FGD 2)

“I feel that I would not want to be the one who tells them. I would prefer that it came from you to them. I mean, I wouldn’t want to challenge my siblings to go for an appointment…but you could send the same letter to them.”(K1, FGD2)

3.3.2. Surprise and Frustration about Current Practice

“So, I’ve gotten this result now, and I’m supposed to sit down and phone around…and I might not know the relatives that well, so maybe I’ll phone the five closest ones, but what happens to the other 10?”(K1, FGD3)

“Yeah, but sure I would think…I think I’d be really pissed off actually if I found out I could have known…and was not given the chance…”(K1, FGD 1)

3.3.3. Wanting Personalized Information to Empower Informed Health Choices

“If I receive it from a good physician, I don’t think I would feel offended by the family member who had not told me because it’s a tough thing to tell. Yeah, I don’t think it would make any difference, or it would, but it would not change my intention to pursue testing myself…”(K1, FGD5)

“…that’s why I think a small folder like this is the way it looks, so that one gets like a visualized family tree…almost with red lines…”(M1, FGD3)

4. Discussion

4.1. A Complex Topic Eliciting Worry and Concern for Others

4.2. Sharing the Responsibility by Collaboration with HCPs

4.3. Surprise about a Missing Link in the Triangle of Stakeholders

4.4. More Personalized Information to Allow Informed Decisions

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- What are your general thoughts about sharing/disclosing cancer risk information?

- How do you think risk disclosure should be handled?

- Who would you want to get this information from?

- How would one want to have this information (in i.e., letters etc.)?

- Is there anything which could make risk disclosure easier?

- Would one need support, and if so, what kind of support?

- What do you think about the individual being asked to inform the extended family?

References

- Brennan, P.; Wild, C.P. Genomics of Cancer and a New Era for Cancer Prevention. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, A.W.; Katz, S.J. Emerging Opportunity of Cascade Genetic Testing for Population-Wide Cancer Prevention and Control. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1371–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, B.W.; Bray, F.; Forman, D.; Ohgaki, H.; Straif, K.; Ullrich, A.; Wild, C.P. Cancer prevention as part of precision medicine: ‘Plenty to be done’. Carcinogenesis 2016, 37, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Auffray, C.; Caulfield, T.; Griffin, J.L.; Khoury, M.J.; Lupski, J.R.; Schwab, M. From genomic medicine to precision medicine: Highlights of 2015. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogowski, W.H.; Grosse, S.D.; Khoury, M.J. Challenges of translating genetic tests into clinical and public health practice. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.C.; Dotson, W.D.; DeVore, C.S.; Bednar, E.M.; Bowen, D.J.; Ganiats, T.G.; Green, R.F.; Hurst, G.M.; Philp, A.R.; Ricker, C.N.; et al. Delivery Of Cascade Screening For Hereditary Conditions: A Scoping Review Of The Literature. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2018, 37, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladabaum, U.; Wang, G.; Terdiman, J.; Blanco, A.; Kuppermann, M.; Boland, C.R.; Ford, J.; Elkin, E.; Phillips, K.A. Strategies to identify the Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marco, M.; DAndrea, E.; Panic, N.; Baccolini, V.; Migliara, G.; Marzuillo, C.; De Vito, C.; Pastorino, R.; Boccia, S.; Villari, P. Which Lynch syndrome screening programs could be implemented in the “real world”? A systematic review of economic evaluations. Genet. Med. 2018, 20, 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forrest, L.E.; Delatycki, M.B.; Skene, L.; Aitken, M. Communicating genetic information in families-a review of guidelines and position papers. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 15, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Branum, R.; Wolf, S.M. International Policies on Sharing Genomic Research Results with Relatives: Approaches to Balancing Privacy with Access. J. Law Med. Ethics 2015, 43, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menko, F.H.; Jeanson, K.N.; Bleiker, E.M.A.; van Tiggelen, C.W.M.; Hogervorst, F.B.L.; Ter Stege, J.A.; Ait Moha, D.; van der Kolk, L.E. The uptake of predictive DNA testing in 40 families with a pathogenic BRCA1/BRCA2 variant. An evaluation of the proband-mediated procedure. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, E.; Stopfer, J.E.; Burlingame, E.; Evans, K.G.; Nathanson, K.L.; Weber, B.L.; Armstrong, K.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Domchek, S.M. Factors determining dissemination of results and uptake of genetic testing in families with known BRCA1/2 mutations. Genet. Test. 2008, 12, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daly, M.B.; Montgomery, S.; Bingler, R.; Ruth, K. Communicating genetic test results within the family: Is it lost in translation? A survey of relatives in the randomized six-step study. Fam. Cancer 2016, 15, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Geus, E.; Aalfs, C.M.; Menko, F.H.; Sijmons, R.H.; Verdam, M.G.; de Haes, H.C.; Smets, E.M. Development of the Informing Relatives Inventory (IRI): Assessing Index Patients’ Knowledge, Motivation and Self-Efficacy Regarding the Disclosure of Hereditary Cancer Risk Information to Relatives. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 22, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaff, C.L.; Clarke, A.J.; Atkinson, P.; Sivell, S.; Elwyn, G.; Iredale, R.; Thornton, H.; Dundon, J.; Shaw, C.; Edwards, A. Process and outcome in communication of genetic information within families: A systematic review. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 15, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phillips, A.; Niemiec, E.; Howard, H.C.; Kagkelari, K.; Borry, P.; Vears, D.F. Communicating genetic information to family members: Analysis of consent forms for diagnostic genomic sequencing. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroutsou, V.; Underhill-Blazey, M.L.; Appenzeller-Herzog, C.; Katapodi, M.C. Interventions Facilitating Family Communication of Genetic Testing Results and Cascade Screening in Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer or Lynch Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijzenga, W.; de Geus, E.; Aalfs, C.M.; Menko, F.H.; Sijmons, R.H.; de Haes, H.; Smets, E.M.A. How to support cancer genetics counselees in informing at-risk relatives? Lessons from a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, J.; Metcalfe, S.; Gaff, C.; Donath, S.; Delatycki, M.B.; Winship, I.; Skene, L.; Aitken, M.; Halliday, J. Outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of a complex genetic counselling intervention to improve family communication. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ajufo, E.; deGoma, E.M.; Raper, A.; Yu, K.D.; Cuchel, M.; Rader, D.J. A randomized controlled trial of genetic testing and cascade screening in familial hypercholesterolemia. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caswell-Jin, J.L.; Zimmer, A.D.; Stedden, W.; Kingham, K.E.; Zhou, A.Y.; Kurian, A.W. Cascade Genetic Testing of Relatives for Hereditary Cancer Risk: Results of an Online Initiative. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.; Borry, P.; Van Hoyweghen, I.; Vears, D.F. Disclosure of genetic information to family members: A systematic review of normative documents. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 2038–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menko, F.; Stege, J.; Kolk, L.; Jeanson, K.; Schats, W.; Moha, D.; Bleiker, E. The uptake of presymptomatic genetic testing in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and Lynch syndrome: A systematic review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. Fam. Cancer 2019, 18, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, J.; Burcher, S.; Kohut, K.; Eastman, N. Ethical Issues in Genetic Testing for Inherited Cancer Predisposition Syndromes: The Potentially Conflicting Interests of Patients and Their Relatives. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2020, 8, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heaton, T.J.; Chico, V. Attitudes towards the sharing of genetic information with at-risk relatives: Results of a quantitative survey. Hum. Genet. 2016, 135, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mackley, M.P.; Fletcher, B.; Parker, M.; Watkins, H.; Ormondroyd, E. Stakeholder views on secondary findings in whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marleen van den Heuvel, L.; Stemkens, D.; van Zelst-Stams, W.A.G.; Willeboordse, F.; Christiaans, I. How to inform at-risk relatives? Attitudes of 1379 Dutch patients, relatives, and members of the general population. J. Genet. Couns. 2019, 29, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cleophat, J.E.; Dorval, M.; El Haffaf, Z.; Chiquette, J.; Collins, S.; Malo, B.; Fradet, V.; Joly, Y.; Nabi, H. Whether, when, how, and how much? General public’s and cancer patients’ views about the disclosure of genomic secondary findings. BMC Med. Genom. 2021, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.; Hawranek, C.; Ofverholm, A.; Ehrencrona, H.; Grill, K.; Hajdarevic, S.; Melin, B.; Tham, E.; Hellquist, B.N.; Rosen, A. Public support for healthcare-mediated discl.losure of hereditary cancer risk information: Results from a population-based survey in Sweden. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2020, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, H.V.; Frederiksen, B.L.; Lautrup, C.K.; Lindberg, L.J.; Ladelund, S.; Nilbert, M. Unsolicited information letters to increase awareness of Lynch syndrome and familial colorectal cancer: Reactions and attitudes. Fam. Cancer 2019, 18, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrikson, N.B.; Blasi, P.; Figueroa Gray, M.; Tiffany, B.T.; Scrol, A.; Ralston, J.D.; Fullerton, S.M.; Lim, C.Y.; Ewing, J.; Leppig, K.A. Patient and Family Preferences on Health System-Led Direct Contact for Cascade Screening. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zordan, C.; Monteil, L.; Haquet, E.; Cordier, C.; Toussaint, E.; Roche, P.; Dorian, V.; Maillard, A.; Lhomme, E.; Richert, L.; et al. Evaluation of the template letter regarding the disclosure of genetic information within the family in France. J. Community Genet. 2019, 10, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, K.; Brun, W.; Kvale, G.; Nordin, K. Confidentiality versus duty to inform--an empirical study on attitudes towards the handling of genetic information. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2007, 143, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollinger, J.M.; Scott, J.; Dvoskin, R.; Kaufman, D. Public preferences regarding the return of individual genetic research results: Findings from a qualitative focus group study. Genet. Med. 2012, 14, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwiter, R.; Rahm, A.K.; Williams, J.L.; Sturm, A.C. How Can We Reach At-Risk Relatives? Efforts to Enhance Communication and Cascade Testing Uptake: A Mini-Review. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2018, 6, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heuvel, L.M.; Smets, E.M.A.; van Tintelen, J.P.; Christiaans, I. How to inform relatives at risk of hereditary diseases? A mixed-methods systematic review on patient attitudes. J. Genet. Couns. 2019, 28, 1042–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzinger, J.; Rosaline, S.B. Developing Focus Group Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausch, A.P.; Menold, N. Methodological Aspects of Focus Groups in Health Research: Results of Qualitative Interviews with Focus Group Moderators. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2016, 3, 2333393616630466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morgan, D. Successful Focus Groups: Advancing the State of the Art; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, OK, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Peek, L.; Fothergill, A. Using focus groups: Lessons from studying daycare centers, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.; Huby, M. The application of vignettes in social and nursing research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 37, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiseman, M.; Dancyger, C.; Michie, S. Communicating genetic risk information within families: A review. Fam. Cancer 2010, 9, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlsma, R.M.; Wouters, R.H.P.; Wessels, H.; May, A.M.; Ausems, M.; Voest, E.E.; Bredenoord, A.L. Managing unsolicited findings in genomics: A qualitative interview study with cancer patients. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarragle, K.M.; Hare, C.; Holter, S.; Facey, D.A.; McShane, K.; Gallinger, S.; Hart, T.L. Examining intrafamilial communication of colorectal cancer risk status to family members and kin responses to colonoscopy: A qualitative study. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2019, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leefmann, J.; Schaper, M.; Schicktanz, S. The Concept of “Genetic Responsibility” and Its Meanings: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Medical Sociology Literature. Front. Sociol. 2017, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van den Nieuwenhoff, H.W.; Mesters, I.; Gielen, C.; de Vries, N.K. Family communication regarding inherited high cholesterol: Why and how do patients disclose genetic risk? Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwiter, R.; Brown, E.; Murray, B.; Kindt, I.; Van Enkevort, E.; Pollin, T.I.; Sturm, A.C. Perspectives from individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia on direct contact in cascade screening. J. Genet. Couns. 2020, 29, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooding, H.C.; Organista, K.; Burack, J.; Biesecker, B.B. Genetic susceptibility testing from a stress and coping perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1880–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, K.; Bjork, J.; Berglund, G. Factors influencing intention to obtain a genetic test for a hereditary disease in an affected group and in the general public. Prev. Med. 2004, 39, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, N.; Jenkins, N.; Douglas, M.; Walker, S.; Finnie, R.; Porteous, M.; Lawton, J. Patients’ experiences and views of cascade screening for familial hypercholesterolemia (FH): A qualitative study. J. Community Genet. 2011, 2, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hardcastle, S.J.; Legge, E.; Laundy, C.S.; Egan, S.J.; French, R.; Watts, G.F.; Hagger, M.S. Patients’ perceptions and experiences of familial hypercholesterolemia, cascade genetic screening and treatment. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 22, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dheensa, S.; Fenwick, A.; Shkedi-Rafid, S.; Crawford, G.; Lucassen, A. Health-care professionals’ responsibility to patients’ relatives in genetic medicine: A systematic review and synthesis of empirical research. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smit, A.K.; Keogh, L.A.; Hersch, J.; Newson, A.J.; Butow, P.; Williams, G.; Cust, A.E. Public preferences for communicating personal genomic risk information: A focus group study. Health Expect. 2016, 19, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höglund-Nielsen, B.; Granskär, M. Tillämpad Kvalitativ Forskning Inom Hälso- Och Sjukvård, 3rd ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lindgren, B.M.; Lundman, B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 56, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elo, S.; Kyngas, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K.; Brun, W.; Kvale, G.; Ehrencrona, H.; Soller, M.; Nordin, K. How to handle genetic information: A comparison of attitudes among patients and the general population. Public Health Genom. 2010, 13, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Meaning Unit | Condensation | Abstraction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text | Condensed text | Code | Sub-category |

| …I think there’s a risk, like I said before, that one might feel a lot of guilt when talking about it, that one think’s it’s my fault passing on this or subjecting someone to… | might feel guilty when disclosing risk info think it’s my fault for passing it on | Feeling guilty | Uncomfortable to talk about cancer risk |

| …I would like to hear it from healthcare…those who work with this…I mean not that you’re supposed to go google this… | like to hear information from HCP not search information by oneself | Wanting information from healthcare | Prefer healthcare to handle disclosure |

| Characteristic | Total | FGD1 | FGD2 | FGD3 | FGD4 | FGD5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Women | 10 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Education | Elementary school or less (<9 years) | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 12 years of school completed | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Graduate studies (>one year) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| University degree/higher education diploma | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Age | 20–29 years | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 30–39 years | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 40–49 years | 2 | 2 | |||||

| 50–59 years | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| 60 or older | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Categories | Descriptive Themes | Overall Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Struggle with unpleasant feelings and consequences Allow type of relationship to govern preferences Recognize that disclosure requires skill and experience | Face an important but difficult challenge | A maze of challenges in a haze of silent expectations |

| Depend on healthcare to take main responsibility Surprise and frustration about current practice Want personalized info to enable informed choice | Expect healthcare to lead but also support disclosure |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hawranek, C.; Hajdarevic, S.; Rosén, A. A Focus Group Study of Perceptions of Genetic Risk Disclosure in Members of the Public in Sweden: “I’ll Phone the Five Closest Ones, but What Happens to the Other Ten?”. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111191

Hawranek C, Hajdarevic S, Rosén A. A Focus Group Study of Perceptions of Genetic Risk Disclosure in Members of the Public in Sweden: “I’ll Phone the Five Closest Ones, but What Happens to the Other Ten?”. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(11):1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111191

Chicago/Turabian StyleHawranek, Carolina, Senada Hajdarevic, and Anna Rosén. 2021. "A Focus Group Study of Perceptions of Genetic Risk Disclosure in Members of the Public in Sweden: “I’ll Phone the Five Closest Ones, but What Happens to the Other Ten?”" Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, no. 11: 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111191

APA StyleHawranek, C., Hajdarevic, S., & Rosén, A. (2021). A Focus Group Study of Perceptions of Genetic Risk Disclosure in Members of the Public in Sweden: “I’ll Phone the Five Closest Ones, but What Happens to the Other Ten?”. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(11), 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111191