Clinical Profile of a Series of Left-Sided Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: Revisiting Surgical Indications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

2.2. Variables Studied

2.3. Definition of Terms

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients with PVE

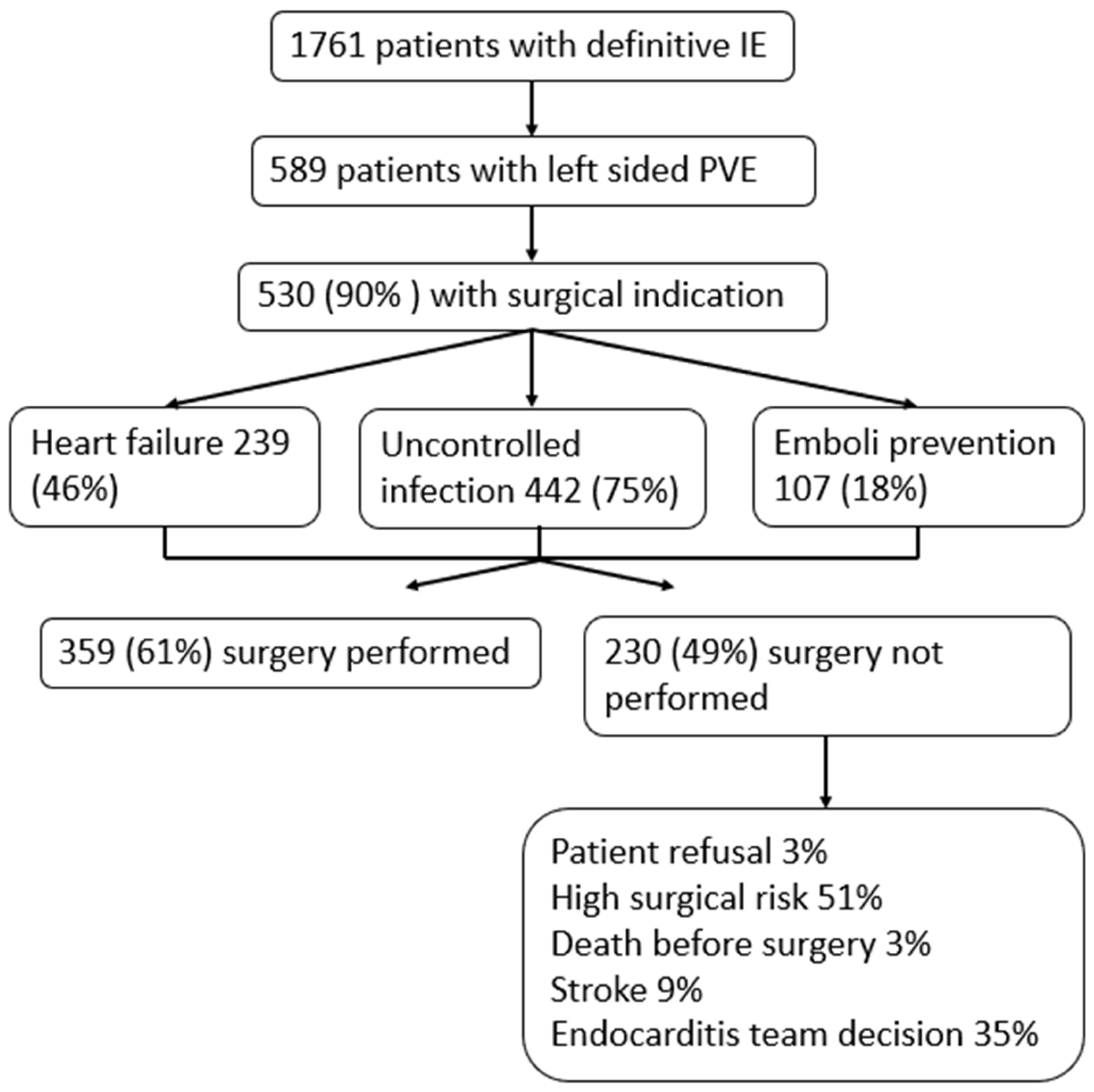

3.2. Surgical Indications

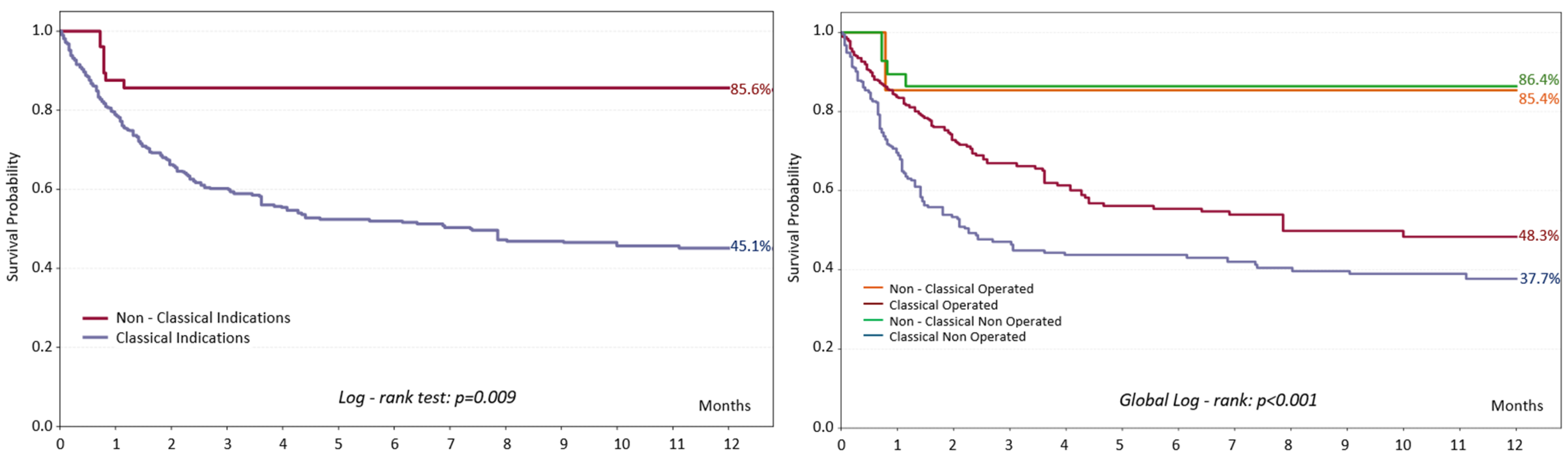

3.3. Mortality Among Patients with PVE

3.4. Patients with ‘’Non-Classical’’ Indications for Surgery

4. Discussion

4.1. Prognostic Factors and Determinants of Mortality

4.2. Evidence of Non-Classical Surgical Indications

4.3. Selection Bias

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PVE | Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis |

| NVE | Native Valve Endocarditis |

| IE | Infective Endocarditis |

| HACEK | Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, and Kingella Group |

| GNB | Gram-Negative Bacteria |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| TTE | Transthoracic Echocardiography |

| TEE | Transesophageal Echocardiography |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

References

- Cuervo, G.; Quintana, E.; Regueiro, A.; Perissinotti, A.; Vidal, B.; Miro, J.M.; Baddour, L.M. The Clinical Challenge of Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: JACC Focus Seminar 3/4. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 1418–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, W.K.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.B.; Jung, S.H.; Choo, S.J.; Chung, C.H.; Lee, J.W. Comparative Surgical Outcomes of Prosthetic and Native Valve Endocarditis. Korean Circ. J. 2021, 51, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Martínez, A.; Domínguez, F.; Muñoz, P.; Marín, M.; Pedraz, Á.; Fariñas, M.C.; Tascón, V.; de Alarcón, A.; Rodríguez-García, R.; Miró, J.M.; et al. Clinical presentation, microbiology, and prognostic factors of prosthetic valve endocarditis. Lessons learned from a large prospective registry. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J. The 2009 ESC Guidelines for management of infective endocarditis reviewed. Eur. Heart J. 2009, 30, 2185–2186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Habib, G.; Lancellotti, P.; Antunes, M.J.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Casalta, J.P.; Del Zotti, F.; Dulgheru, R.; El Khoury, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3075–3128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Remadi, J.P.; Habib, G.; Nadji, G.; Brahim, A.; Thuny, F.; Casalta, J.P.; Peltier, M.; Tribouilloy, C. Predictors of death and impact of surgery in Staphylococcus aureus infective endocarditis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007, 83, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón Parra, J.; De Castro-Campos, D.; Muñoz García, P.; Olmedo Samperio, M.; Marín Arriaza, M.; De Alarcón, A.; Gutierrez-Carretero, E.; Fariñas Alvarez, M.C.; Miró Meda, J.M.; Goneaga Sanchez, M.Á.; et al. Non-HACEK gram negative bacilli endocarditis: Analysis of a national prospective cohort. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 92, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; Donal, E.; Cosyns, B.; Laroche, C.; Popescu, B.A.; Prendergast, B.; Tornos, P.; Sadeghpour, A.; et al. Clinical presentation, aetiology and outcome of infective endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European infective endocarditis) registry: A prospective cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3222–3232, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, V.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; de Waha, S.; Bonaros, N.; Brida, M.; Burri, H.; Caselli, S.; Doenst, T.; Ederhy, S.; Erba, P.A.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3948–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancellotti, P.; Tribouilloy, C.; Hagendorff, A.; Popescu, B.A.; Edvardsen, T.; Pierard, L.A.; Badano, L.; Zamorano, J.L.; Scientific Document Committee of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurgitation: An executive summary from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 14, 611–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Motta, I. Anemia in Clinical Practice-Definition and Classification: Does Hemoglobin Change With Aging? Semin. Hematol. 2015, 52, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peláez Ballesta, A.I.; García Vázquez, E.; Gómez Gómez, J. Infective endocarditis treated in a secondary hospital: Epidemiological, clinical, microbiological characteristics and prognosis, with special reference to patients transferred to a third level hospital. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. Publ. Soc. Esp. Quimioter. 2022, 35, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, Z.; McTiernan, C.D.; Suuronen, E.J.; Mah, T.F.; Alarcon, E.I. Bacterial biofilm formation on implantable devices and approaches to its treatment and prevention. Heliyon 2018, 4, e01067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Tang, X.; Dong, W.; Sun, N.; Yuan, W. A Review of Biofilm Formation of Staphylococcus aureus and Its Regulation Mechanism. Antibiotics 2022, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Athan, E.; Pappas, P.A.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Olaison, L.; Paré, C.; Almirante, B.; Muñoz, P.; Rizzi, M.; Naber, C.; et al. Contemporary clinical profile and outcome of prosthetic valve endocarditis. JAMA 2007, 297, 1354–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diego-Yagüe, I.; Ramos-Martínez, A.; Muñoz, P.; Martínez-Sellés, M.; Machado, M.; de Alarcón, A.; Miró, J.M.; Rodríguez-Gacía, R.; Gutierrez-Díez, J.F.; Hidalgo-Tenorio, C.; et al. Clinical features and prognosis of prosthetic valve endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 43, 1989–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Valle, H.; Fariñas-Alvarez, C.; García-Palomo, J.D.; Bernal, J.M.; Martín-Durán, R.; Gutiérrez Díez, J.F.; Revuelta, J.M.; Fariñas, M.C. Clinical course and predictors of death in prosthetic valve endocarditis over a 20-year period. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 139, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Sevilla, T.; Vilacosta, I.; Sarriá, C.; Revilla, A.; Ortiz, C.; Ferrera, C.; Olmos, C.; Gómez, I.; San Román, J.A. Prognostic role of persistent positive blood cultures after initiation of antibiotic therapy in left-sided infective endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1749–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciani, N.; Mossuto, E.; Ricci, D.; Luciani, M.; Russo, M.; Salsano, A.; Pozzoli, A.; Pierri, M.D.; D’Onofrio, A.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. Prosthetic valve endocarditis: Predictors of early outcome of surgical therapy. A multicentric study. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2017, 52, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.C.; Anguita, M.P.; Torres, F.; Mesa, D.; Franco, M.; González, E.; Muñoz, I.; Vallés, F. Long-term prognosis of early and late prosthetic valve endocarditis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2004, 93, 1185–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou-Olivgeris, M.; Ledergerber, B.; Siedentop, B.; Monney, P.; Frank, M.; Tzimas, G.; Tozzi, P.; Kirsch, M.; Epprecht, J.; van Hemelrijck, M.; et al. Beyond the Timeline: 1-Year Mortality Trends in Early Versus Late Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 80, 804–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirouze, C.; Cabell, C.H.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Khayat, N.; Olaison, L.; Miro, J.M.; Habib, G.; Abrutyn, E.; Eykyn, S.; Corey, G.R.; et al. Prognostic factors in 61 cases of Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic valve infective endocarditis from the International Collaboration on Endocarditis merged database. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 1323–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalani, T.; Chu, V.H.; Park, L.P.; Cecchi, E.; Corey, G.R.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Gordon, D.; Grossi, P.; Hannan, M.; et al. In-hospital and 1-year mortality in patients undergoing early surgery for prosthetic valve endocarditis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (589) | No Surgery (230) | Surgery (359) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiologic variables | ||||

| Age, years | 68.6 ± 12 | 72 ± 11 | 66 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Male | 62.5% (368) | 61.3% (141) | 63.2 (227) | 0.638 |

| Referred | 43.8% (258) | 34.4% (77) | 51.4% (181) | <0.001 |

| Acute onset | 60.2% (353) | 66.4% (152) | 56.3% (201) | 0.015 |

| Diabetes | 26.3% (155) | 30.9% (71) | 23.4% (84) | 0.045 |

| Cancer | 10.5% (62) | 14.3% (33) | 8.1% (29) | 0.016 |

| Anemia | 23.6% (139) | 29.6% (68) | 19.8% (71) | 0.007 |

| COPD | 10.4% (61) | 13.9% (32) | 8.1% (29) | 0.024 |

| Chronic kidney injury | 17.5% (103) | 22.6% (52) | 14.2% (51) | 0.009 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16.8% (95) | 18.4% (40) | 15.9% (55) | 0.425 |

| Microbiological variables | ||||

| Streptococcus gallolyticus | 3.9% (23) | 3.5% (8) | 4.2% (15) | 0.676 |

| Viridans streptococci | 8.8% (52) | 11.4% (26) | 7.2% (26) | 0.087 |

| Enterococci | 15.1% (89) | 21.4% (49) | 11.1% (40) | 0.001 |

| Other streptococci | 2.6% (15) | 2.6% (6) | 2.5% (9) | 0.932 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 16.5% (97) | 21.4% (49) | 13.4% (48) | 0.011 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 26.2% (154) | 20.1% (46) | 30.1% (108) | 0.007 |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 4.9% (29) | 4.8% (11) | 5% (18) | 0.909 |

| Fungi | 3.7% (22) | 1.3% (3) | 5.3% (19) | 0.013 |

| HACEK | 0.3% (2) | 0.4% (1) | 0.3% (1) | 0.999 |

| Anaerobic bacteria | 4.6% (27) | 1.3% (3) | 6.7% (24) | 0.002 |

| Negative cultures | 14.6% (86) | 13.5% (31) | 15.3% (55) | 0.551 |

| Positive cultures at admission | 76.2% (413) | 82.5% (184) | 71.8% (229) | 0.004 |

| Positive cultures after 48 h | 30.8% (117) | 34% (52) | 28.6% (65) | 0.268 |

| Clinical variables at admission | ||||

| Emboli at admission | 16.9% (99) | 18.4% (42) | 15.9% (57) | 0.422 |

| Heart failure at admission | 39.9% (234) | 38.6% (88) | 40.7% (146) | 0.617 |

| AKI at admission | 23% (135) | 30.7% (70) | 18.1% (65) | <0.001 |

| Stroke at admission | 11.1% (65) | 11.4% (26) | 10.9% (39) | 0.839 |

| Septic shock at admission | 7.5% (44) | 10.5% (24) | 5.6% (20) | 0.026 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 30.6% (175) | 29% (64) | 31.6% (111) | 0.501 |

| Early PVE | 22.2% (131) | 18.7% (43) | 24.5% (88) | 0.098 |

| Echocardiographic variables | ||||

| Aortic prosthesis | 61% (359) | 56.1% (129) | 64.1% (230) | 0.053 |

| Mitral prosthesis | 48.4% (285) | 49.6% (114) | 47.6% (171) | 0.647 |

| Mechanical prothesis | 59.8% (352) | 55.7% (128) | 62.4% (224) | 0.103 |

| Biological prosthesis | 41.1% (242) | 44.3% (102) | 39% (140) | 0.198 |

| Vegetation | 78.3% (451) | 83.9% (187) | 74.8% (264) | 0.01 |

| Periannular complication | 35.9% (207) | 23.3% (52) | 43.9% (155) | <0.001 |

| Severe regurgitation | 26.6% (153) | 13% (29) | 35.1% (124) | <0.001 |

| Evolutive variables | ||||

| Septic shock | 15.8% (93) | 22.4% (51) | 11.7% (42) | 0.001 |

| Emboli | 26.4% (155) | 28.5% (65) | 25.1% (90) | 0.357 |

| Heart failure | 49.2% (289) | 50.4% (115) | 48.5% (174) | 0.642 |

| Acute kidney injury | 39% (229) | 49.6% (113) | 32.3% (116) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 16.2% (95) | 18.4% (42) | 14.8% (53) | 0.241 |

| Mortality | ||||

| In-hospital mortality | 31.4% (185) | 41.3% (95) | 25.1% (90) | < 0.001 |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p Value | OR (95%CI) | p Value | |

| Age | 1.03 (1.09–1.04) | 0.002 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.75 (1.19–2.57) | 0.004 | ||

| COPD | 2.34 (1.37–4.01) | 0.002 | 2.22 (1.21–4.09) | 0.010 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1.80 (1.24–2.62) | 0.002 | 1.75 (1.12–2.74) | 0.014 |

| Periannular complications | 1.65 (1.15–2.37) | 0.007 | 2.16 (1.41–3.32) | <0.001 |

| Early PVE | 0.68 (0.44–1.05) | 0.083 | ||

| Viridans streptococci | 0.26 (0.11–0.63) | 0.003 | 0.36 (0.14–0.92) | 0.033 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3.31 (2.12–5.18) | <0.001 | 2.94 (1.75–4.92) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure at admission | 2.20 (1.55–3.14) | <0.001 | 1.82 (1.18–2.74) | 0.014 |

| Septic shock at admission | 4.30 (2.27–8.17) | <0.001 | 2.31 (1.09–4.90) | 0.029 |

| Renal failure at admission | 3.16 (2.12–4.70) | <0.001 | 2.22 (1.40–3.52) | 0.001 |

| Surgery | 0.48 (0.33–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.45 (0.30–0.70) | <0.001 |

| Total (530) | Classical Indications (502) | Only Non-Classical Indications (28) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiological variables | ||||

| Age, years | 68 ± 12 | 68.5 ± 11.9 | 66.8 ± 11.6 | 0.283 |

| Male | 62.5% (331) | 63.5% (319) | 42.9% (12) | 0.028 |

| Referred | 46.6% (242) | 47.4% (233) | 33.3% (9) | 0.155 |

| Nosocomial | 32.8% (174) | 31.3% (157) | 60.7% (17) | 0.001 |

| Acute onset | 60.2% (318) | 59.1% (296) | 81.5% (22) | 0.021 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27.0% (143) | 26.5% (133) | 35.7% (10) | 0.285 |

| COPD | 10.4% (55) | 10.4% (52) | 10.7% (3) | 0.999 |

| Cancer | 10.4% (55) | 10.8% (54) | 3.6% (1) | 0.343 |

| Anemia | 23.6% (125) | 24.0% (120) | 17.9% (5) | 0.460 |

| Chronic kidney injury | 17.0% (90) | 16.9% (85) | 17.9% (5) | 0.801 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16.7% (86) | 16.4% (80) | 22.2% (6) | 0.427 |

| Microbiological variables | ||||

| Streptococcus gallolyticus | 4.0% (21) | 4.2% (21) | 0.0% (0) | 0.619 |

| Viridans streptococci | 7.4% (39) | 7.0% (35) | 14.3% (4) | 0.143 |

| Enterococci | 14.6% (77) | 15.0% (75) | 7.1% (2) | 0.406 |

| Other streptococci | 2.3% (12) | 2.2% (11) | 3.6% (1) | 0.483 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 18.3% (97) | 17.0% (85) | 42.9% (12) | 0.001 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 26.5% (140) | 26.7% (134) | 21.4% (6) | 0.535 |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 5.5% (29) | 4.8% (24) | 17.9% (5) | 0.014 |

| Fungi | 4.2% (22) | 4.2% (21) | 3.6% (1) | 0.999 |

| HACEK | 0.4% (2) | 0.4% (2) | 0.0% (0) | 0.999 |

| Anaerobic bacteria | 4.5% (24) | 4.8% (24) | 0.0% (0) | 0.630 |

| Negative cultures | 14.4% (76) | 14.8% (74) | 7.1% (2) | 0.405 |

| Positive cultures at admission | 76.0% (373) | 74.8% (347) | 96.3% (26) | 0.011 |

| Positive cultures after 48 h | 34.1% (117) | 36.0% (117) | 0.0% (0) | 0.002 |

| Clinical variables at admission | ||||

| Emboli at admission | 17.7% (94) | 17.7% (89) | 17.9% (5) | 0.999 |

| Heart failure at admission | 41.7% (221) | 42.6% (214) | 25.0% (7) | 0.066 |

| AKI at admission | 23.2% (123) | 23.7% (119) | 14.3% (4) | 0.251 |

| Stroke at admission | 11.7% (62) | 12.0% (60) | 7.1% (2) | 0.760 |

| Septic shock at admission | 8.3% (44) | 8.8% (44) | 0.0% (0) | 0.155 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 31.7% (165) | 32.5% (160) | 17.9% (5) | 0.106 |

| Early PVE | 24.7% (131) | 22.5% (113) | 64.3% (18) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiographic variables | ||||

| Mitral prosthesis | 47.4% (251) | 46.0% (231) | 71.4% (20) | 0.009 |

| Aortic prosthesis | 62.6% (332) | 64.3% (323) | 32.1% (9) | 0.001 |

| Mechanical prosthesis | 60.0% (318) | 59.4% (298) | 71.4% (20) | 0.205 |

| Biological prosthesis | 40.9% (217) | 41.6% (209) | 28.6% (8) | 0.171 |

| Vegetation | 78.5% (413) | 77.7% (387) | 92.9% (26) | 0.058 |

| Periannular complication | 39.4% (207) | 41.6% (207) | 0.0% (0) | <0.001 |

| Valve perforation | 3.8% (20) | 4.0% (20) | 0.0% (0) | 0.617 |

| Severe regurgitation | 28.7% (151) | 30.3% (151) | 0.0% (0) | 0.001 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Surgery | 63.2% (335) | 64.7% (325) | 35.7% (10) | 0.002 |

| In-hospital mortality | 34.0% (180) | 35.1% (176) | 14.3% (4) | 0.024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ibáñez, A.L.; Díaz, J.L.; Álava, M.d.M.; Cabezón Villalba, G.; Oña Orive, A.; Gómez-Ramírez, D.; Landín, P.; Pérez-Camargo, D.; Campillo, S.; Gómez-Salvador, I.; et al. Clinical Profile of a Series of Left-Sided Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: Revisiting Surgical Indications. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030426

Ibáñez AL, Díaz JL, Álava MdM, Cabezón Villalba G, Oña Orive A, Gómez-Ramírez D, Landín P, Pérez-Camargo D, Campillo S, Gómez-Salvador I, et al. Clinical Profile of a Series of Left-Sided Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: Revisiting Surgical Indications. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(3):426. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030426

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbáñez, Adrián Lozano, Javier López Díaz, María de Miguel Álava, Gonzalo Cabezón Villalba, Andrea Oña Orive, Daniel Gómez-Ramírez, Patricia Landín, Daniel Pérez-Camargo, Sofía Campillo, Itziar Gómez-Salvador, and et al. 2026. "Clinical Profile of a Series of Left-Sided Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: Revisiting Surgical Indications" Diagnostics 16, no. 3: 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030426

APA StyleIbáñez, A. L., Díaz, J. L., Álava, M. d. M., Cabezón Villalba, G., Oña Orive, A., Gómez-Ramírez, D., Landín, P., Pérez-Camargo, D., Campillo, S., Gómez-Salvador, I., Sáez, C., Olmos, C., Vilacosta, I., & San Román, J. A. (2026). Clinical Profile of a Series of Left-Sided Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: Revisiting Surgical Indications. Diagnostics, 16(3), 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030426