Deep Learning-Based Liver Tumor Segmentation from Computed Tomography Scans with a Gradient-Enhanced Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. CNN-Based Segmentation Networks

2.2. Transformer-Based and Hybrid Segmentation Networks

2.3. Liver and Tumor Segmentation Networks

3. Materials and Methods

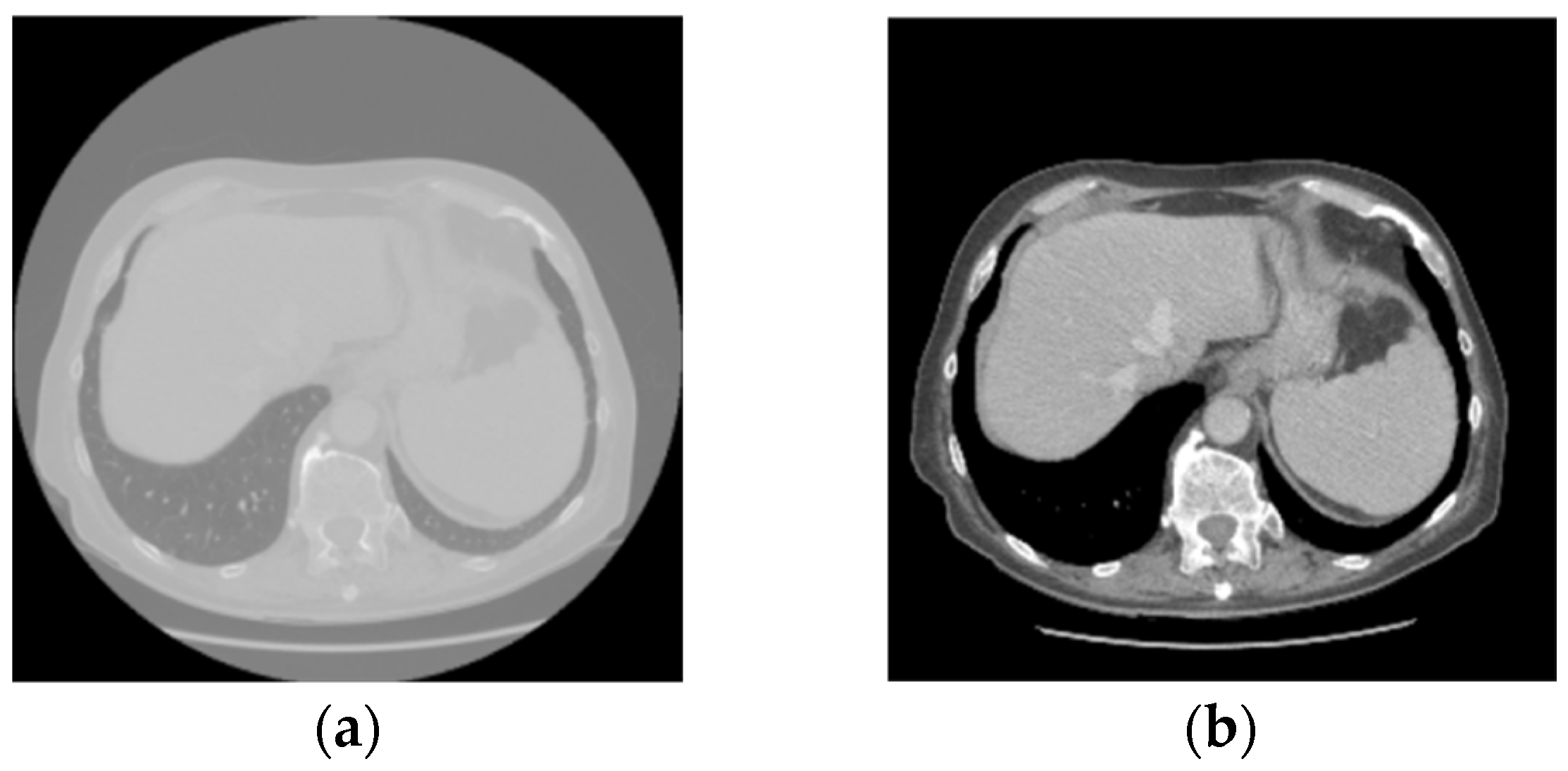

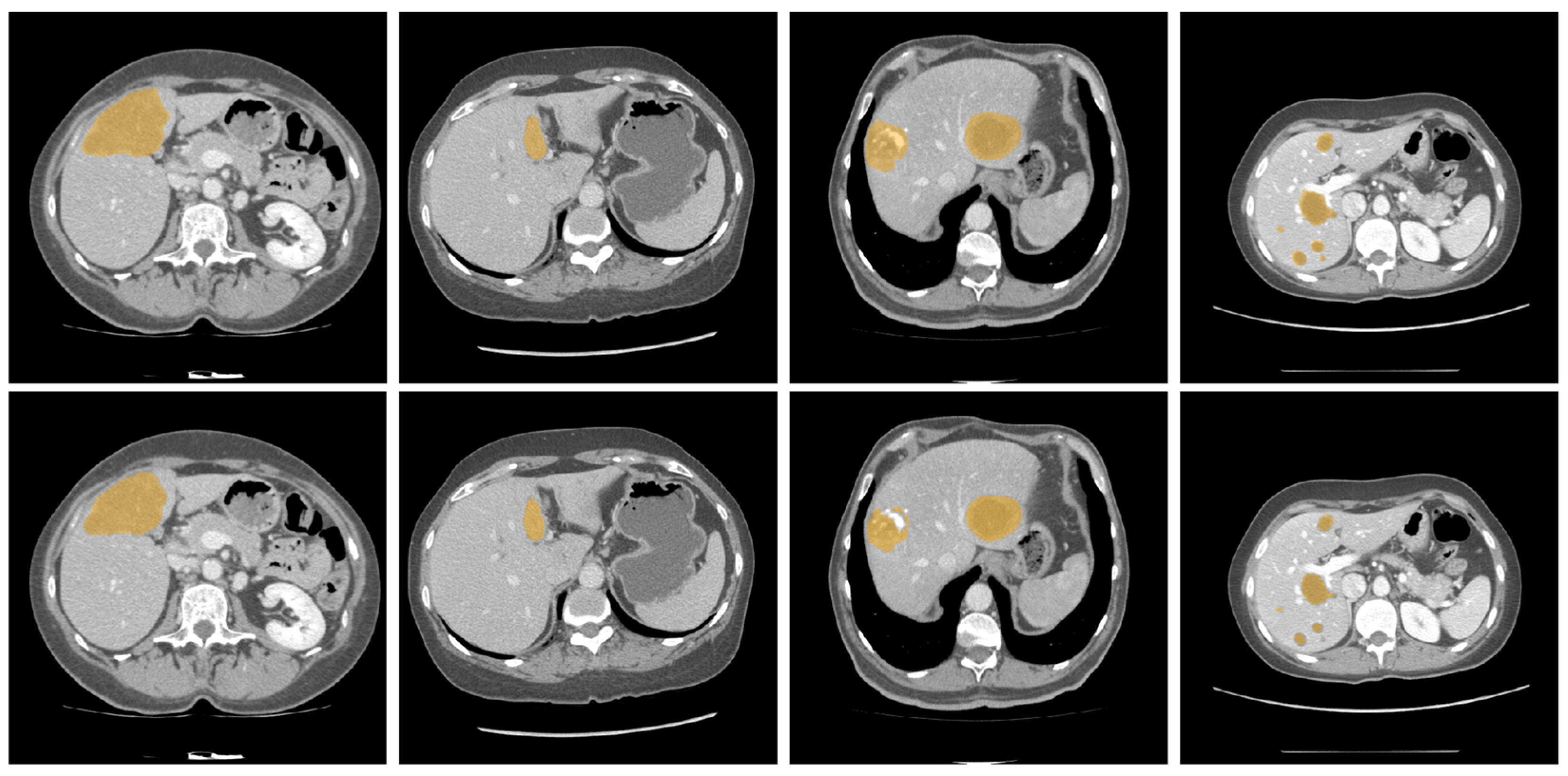

3.1. Data Preparation

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

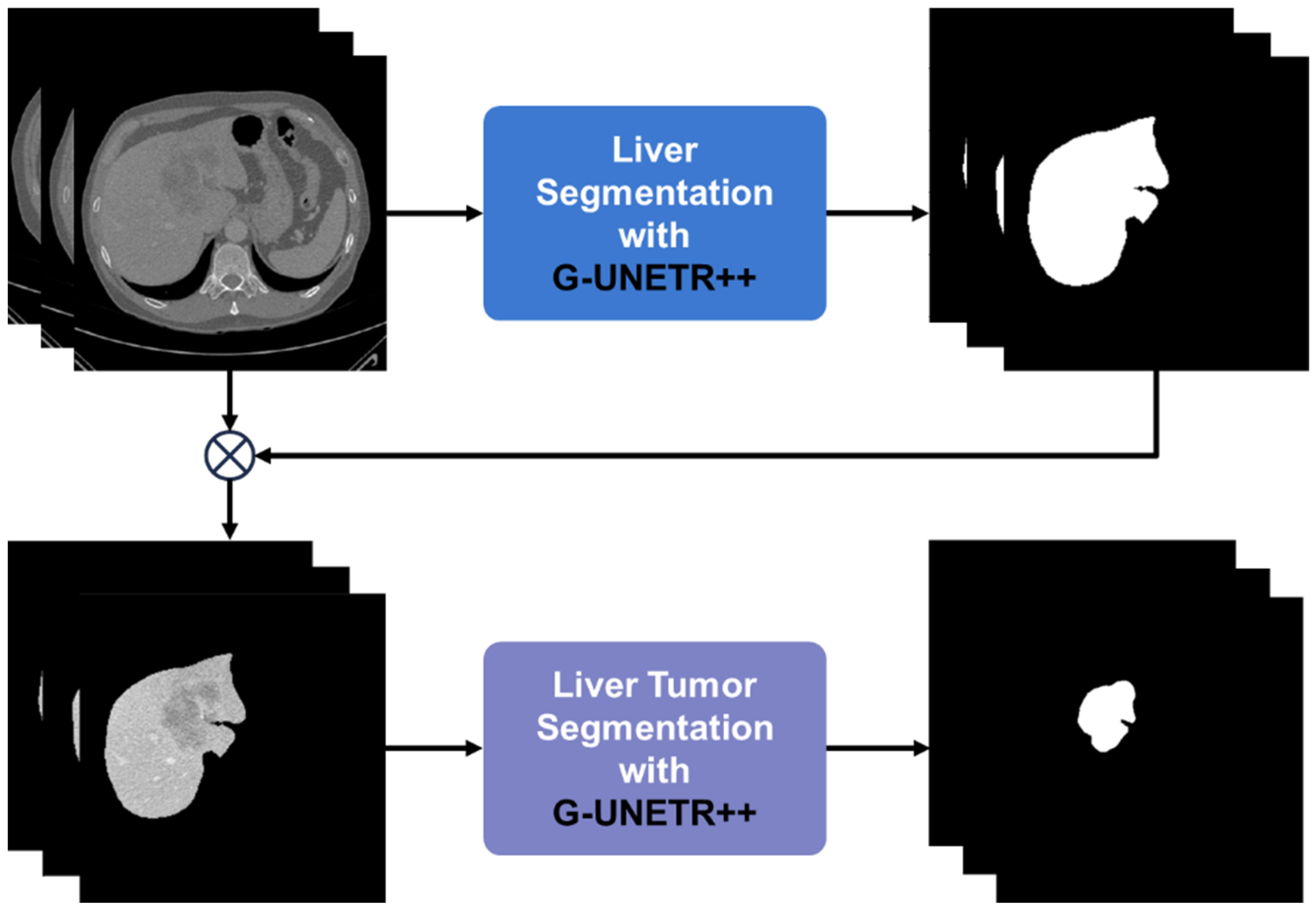

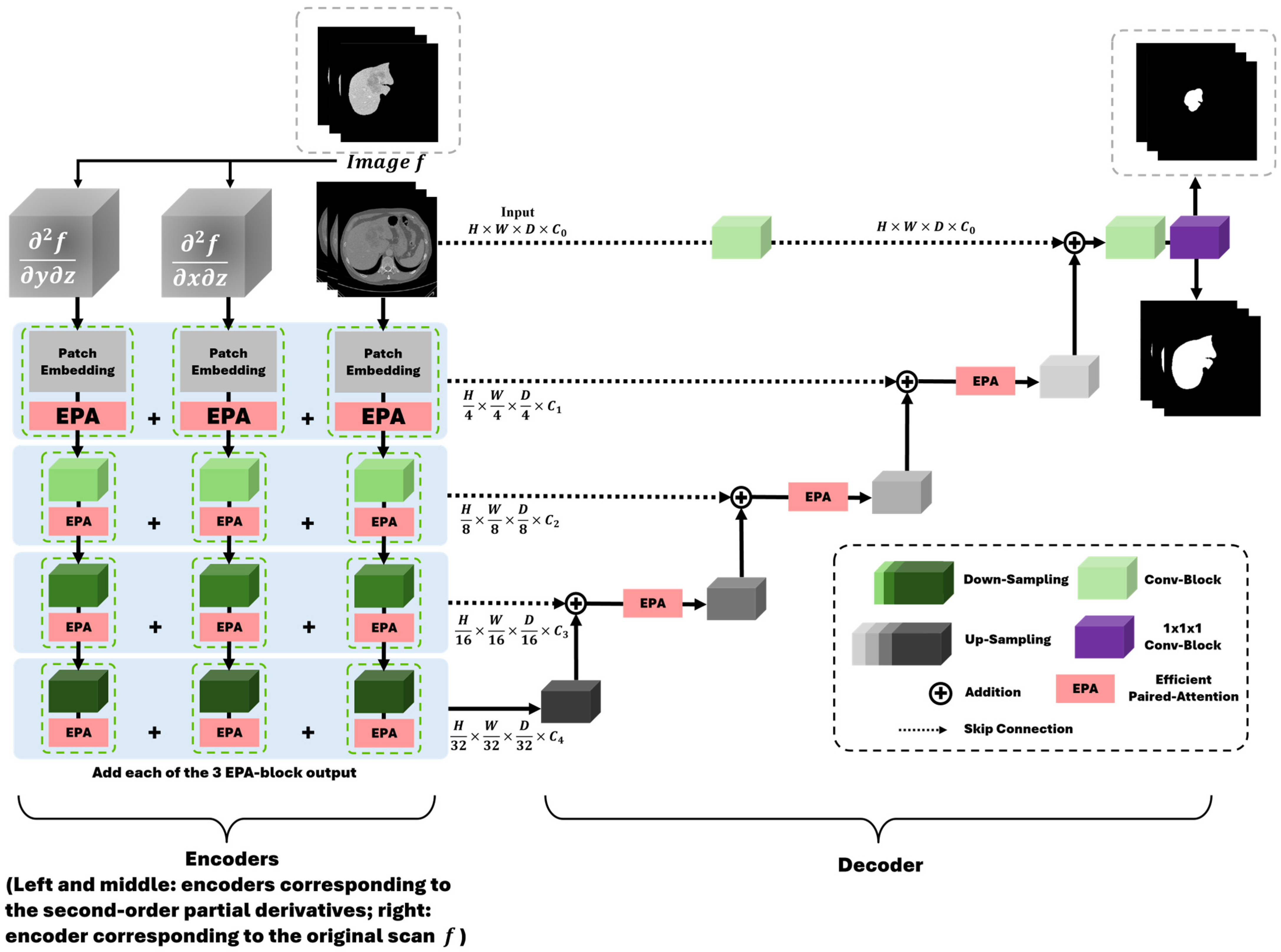

3.3. Deep Learning Model Preparation and Training

3.4. Loss Function

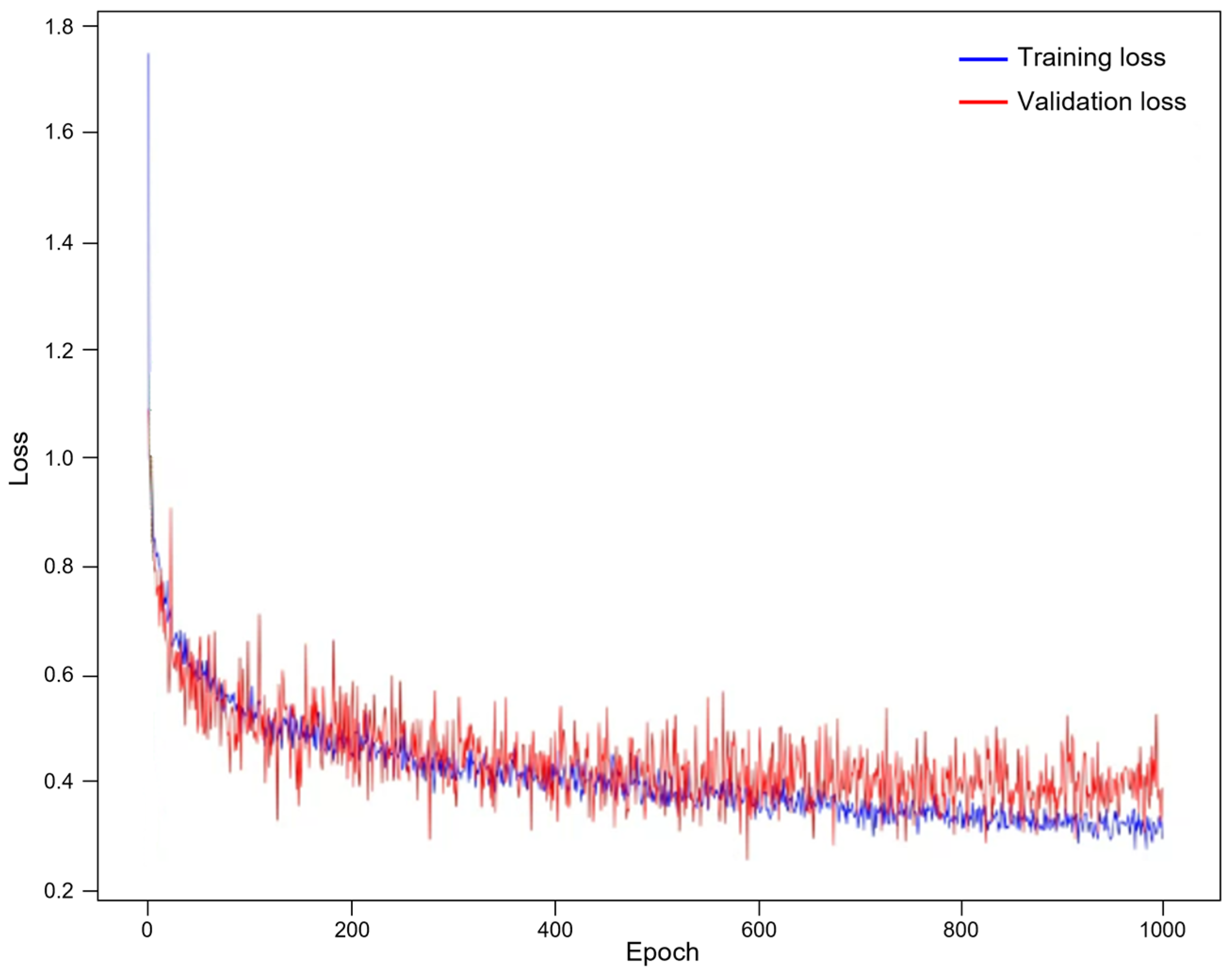

3.5. Model Training

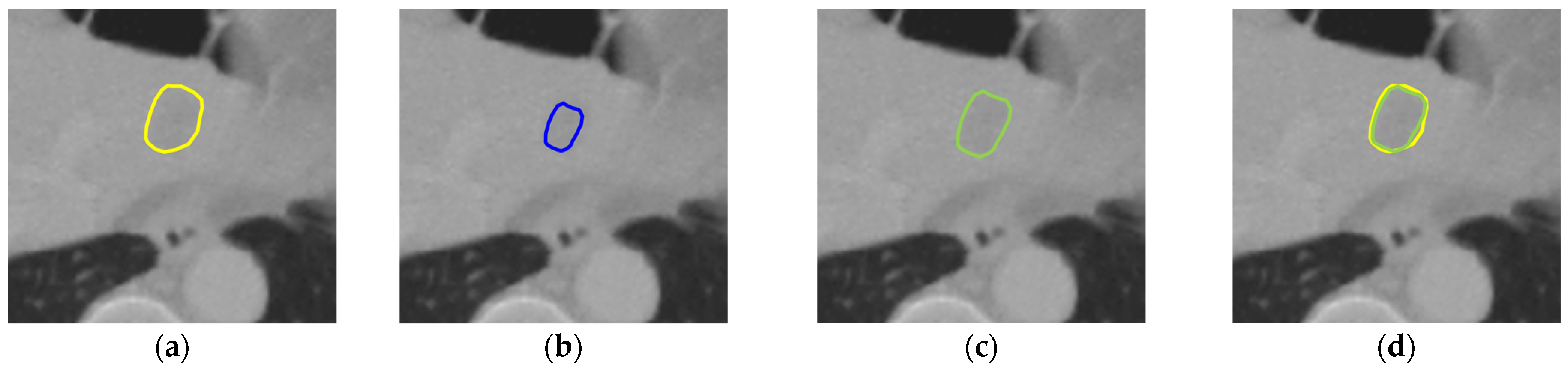

3.6. Post-Processing

3.7. Evaluation Metrics

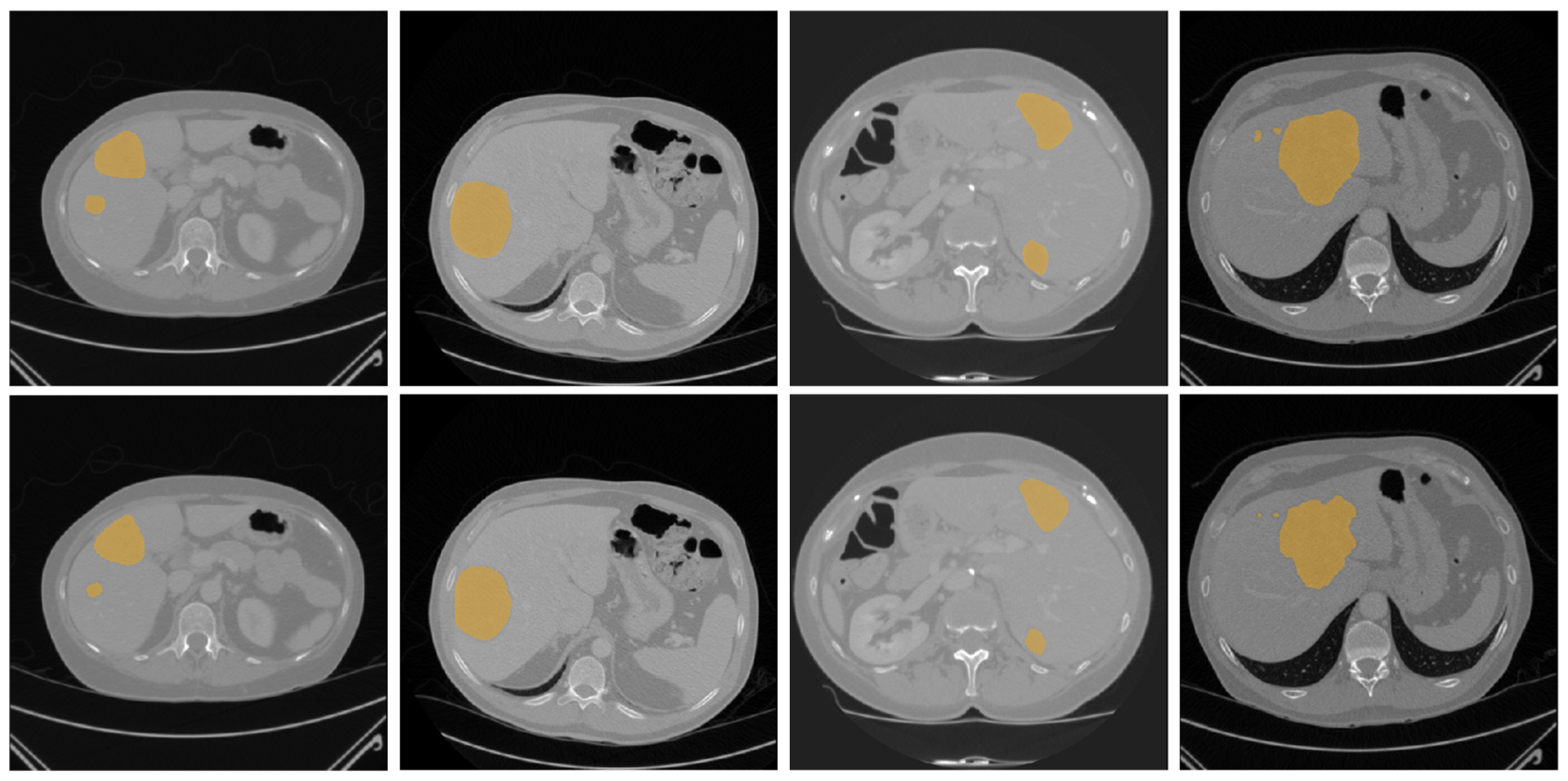

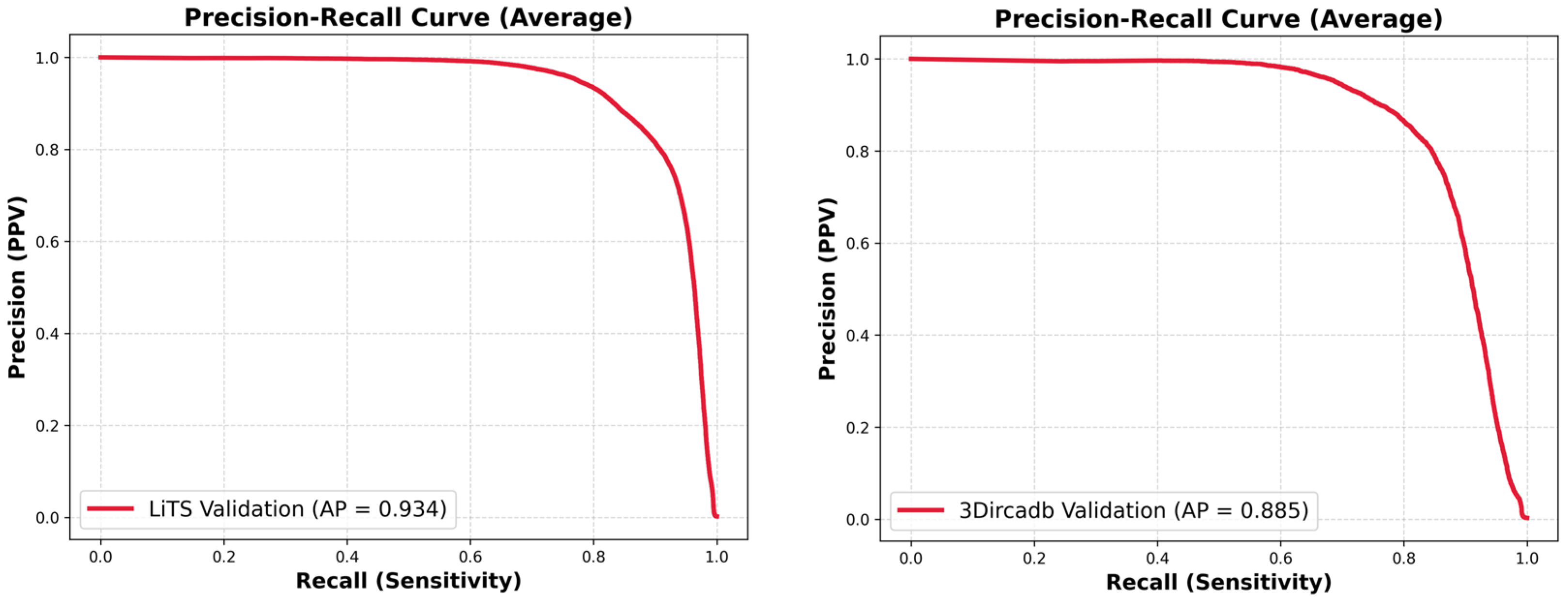

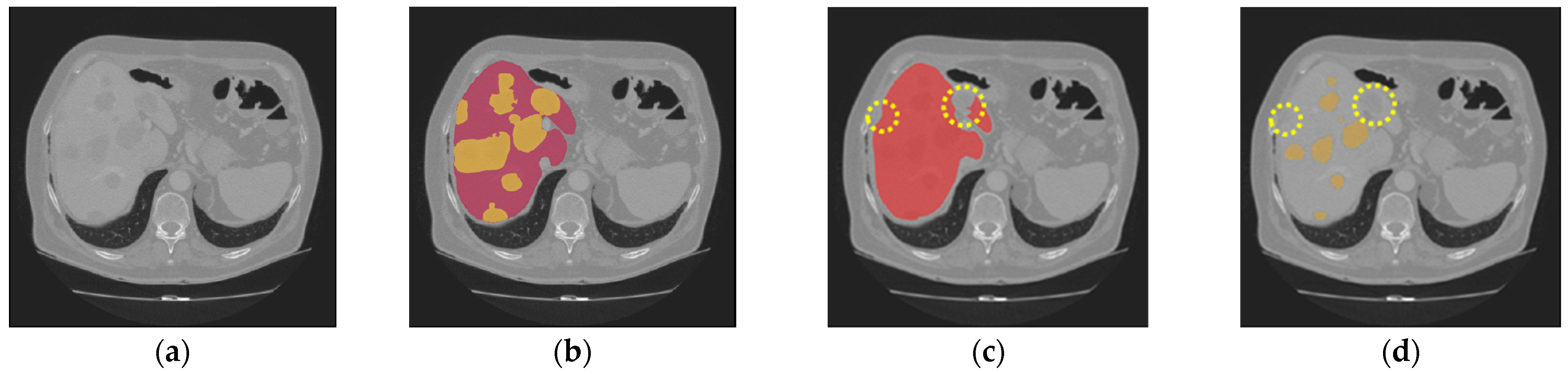

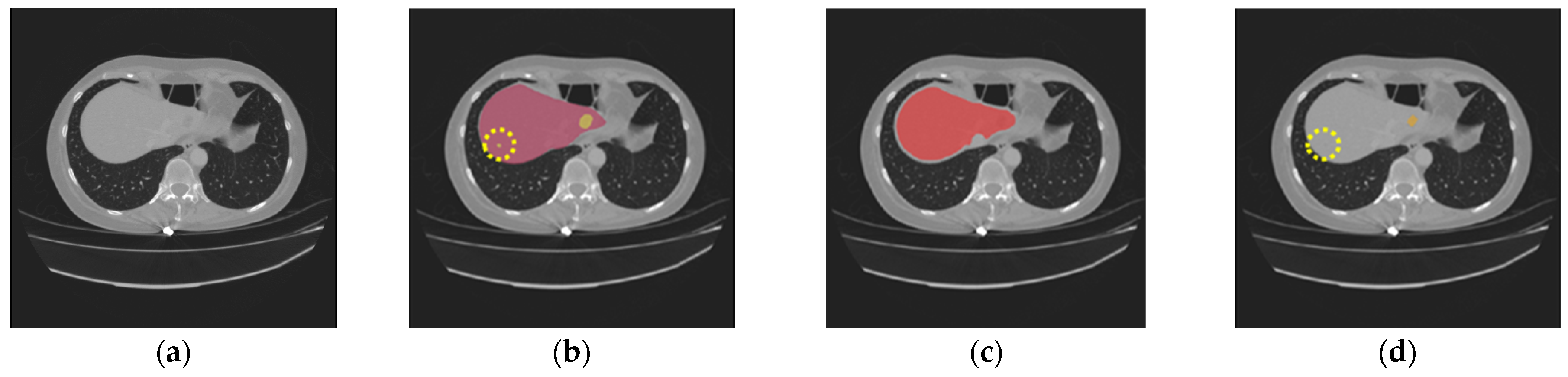

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, S.H.; Yeo, A.U.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, C.; Goh, Y.; Cho, S.; Lee, S.B.; Lim, Y.K.; Kim, H.; Shin, D.; et al. Comparative clinical evaluation of atlas and deep-learning-based auto-segmentation of organ structures in liver cancer. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 14, 213. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, W.; Lin, H.; Chen, W.; Zhang, G.; Xu, G.; Wu, F. MS-FANet: Multi-scale feature attention network for liver tumor segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 163, 107208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2016, Athens, Greece, 17–21 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support: 4th International Workshop, DLMIA 2018, and 8th International Workshop, ML-CDS 2018, Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: Redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 39, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Tian, Y.; Lui, H.; Zeng, H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, G. Dense-UNet: A novel multiphoton in vivo cellular image segmentation model based on a convolutional neural network. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2020, 10, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Kaur, L.; Singh, A. GA-UNet: UNet-based framework for segmentation of 2D and 3D medical images applicable on heterogeneous datasets. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 14991–15025. [Google Scholar]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.-A. V-Net: Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Volumetric Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, Q.; Chen, H.; Jin, Y.; Yu, L.; Qin, J.; Heng, P.A. 3D Deeply Supervised Network for Automatic Liver Segmentation from CT Volumes. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2016, Athens, Greece, 17–21 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, H.; Qi, X.; Dou, Q.; Fu, C.-W.; Heng, P.-A. H-DenseUNet: Hybrid densely connected UNet for liver and tumor segmentation from CT volumes. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 2663–2674. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, H.R.; Oda, H.; Hayashi, Y.; Oda, M.; Shimizu, N.; Fujiwara, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K. Hierarchical 3D fully convolutional networks for multi-organ segmentation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.06382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, P.F.; Ettlinger, F.; Grün, F.; Elshaera, M.E.A.; Lipkova, J.; Schlecht, S.; Ahmaddy, F.; Tatavarty, S.; Bickel, M.; Bilic, P.; et al. Automatic liver and tumor segmentation of CT and MRI volumes using cascaded fully convolutional neural networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.05970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, X.; Li, C.; Wu, T. 3D liver and tumor segmentation with CNNs based on region and distance metrics. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Chow, P.K. Multi-Slice Dense-Sparse Learning for Efficient Liver and Tumor Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Virtual, 1–5 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, F.; Uçan, O.N.; Karaçam, S.; Tunçman, D. Fully automatic liver and tumor segmentation from CT images using an AIM-Unet. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Z.; Lin, S. Local Relation Networks for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3464–3473. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Han, K.; Shin, H.; Park, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.D.; Yu, H.C.; You, H. G-UNETR++: A gradient-enhanced network for accurate and robust liver segmentation from computed tomography images. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, D.; Vasylechko, S.D.; Gholipour, A. Convolution-free medical image segmentation using transformers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-Unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valanarasu, J.M.J.; Oza, P.; Hacihaliloglu, I.; Patel, V.M. Medical transformer: Gated axial-attention for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Tang, Y.; Nath, V.; Yang, D.; Myronenko, A.; Landman, B.; Roth, H.R.; Xu, D. UNETR: Transformers for 3D Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 574–584. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.-Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y. nnFormer: Volumetric medical image segmentation via a 3D transformer. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 4036–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, A.; Maaz, M.; Rasheed, H.; Khan, S.; Yang, M.H.; Khan, F.S. UNETR++: Delving into Efficient and Accurate 3D Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 3088–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Yan, P. Multi-organ segmentation over partially labeled datasets with multi-scale feature abstraction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 3619–3629. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Hu, Q. Transfuse: Fusing transformers and cnns for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, C.; Xia, Y. CoTr: Efficiently bridging CNN and transformer for 3D medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q.; Meng, Z.; Sun, C.; Cui, H.; Su, R. RA-UNet: A hybrid deep attention-aware network to extract liver and tumor in CT scans. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 1471. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, J.; Hua, Q.; Li, C.; Wang, P. SAA-Net: U shaped network with Scale-Axis-Attention for liver tumor segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 73, 103460. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Ou, J.; Liu, R.; Zou, Y.; Xie, T.; Xiao, H.; Bai, T. RMAU-Net: Residual multi-scale attention U-Net for liver and tumor segmentation in CT images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 158, 106838. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, S.; Zhang, J. Segmentation of Liver Tumors by Monai and PyTorch in CT Images with Deep Learning Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashaswini, G.N.; Manjunath, R.V.; Shubha, B.; Prabha, P.; Aishwarya, N.; Manu, H.M. Deep learning technique for automatic liver and liver tumor segmentation in CT images. J. Liver Transplant. 2025, 17, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer-Montero, M.; Marcos Morales, A.; Ligero, M.; Zatse, C.; Leiva, D.; Atlagich, L.M.; Staikoglou, N.; Viaplana, C.; Monreal, C.; Mateo, J.; et al. A CT-based deep learning-driven tool for automatic liver tumor detection and delineation in patients with cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102032. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P. Liver Tumor Segmentation Based on Multi-Scale Deformable Feature Fusion and Global Context Awareness. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilic, P.; Christ, P.; Li, H.B.; Vorontsov, E.; Ben-Cohen, A.; Kaissis, G.; Szeskin, A.; Jacobs, C.; Mamani, G.E.H.; Chartrand, G.; et al. The liver tumor segmentation benchmark (LiTS). Med. Image Anal. 2023, 84, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler, L.; Hosttettle, A.; Charnoz, A.; Fasquel, J.; Moreau, J. 3D Image Reconstruction for Comparison of Algorithm Database: A Patient Specific Anatomical and Medical Image Database. Available online: https://www.ircad.fr/research/data-sets/liver-segmentation-3d-ircadb-01/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Karimi, D.; Salcudean, S.E. Reducing the hausdorff distance in medical image segmentation with convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.Y.; Xie, S.; Gallagher, P.; Zhang, Z.; Tu, Z. Deeply-Supervised Nets. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, San Diego, CA, USA, 9–12 May 2015; pp. 562–570. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015—Conference Track Proceedings, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, F.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, C. Hybrid-attention densely connected U-Net with GAP for extracting livers from CT volumes. Med. Phys. 2022, 49, 1015–1033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diakogiannis, F.I.; Waldner, F.; Caccetta, P.; Wu, C. ResUNet-a: A deep learning framework for semantic segmentation of remotely sensed data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 162, 94–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kushnure, D.T.; Talbar, S.N. HFRU-Net: High-level feature fusion and recalibration unet for automatic liver and tumor segmentation in CT images. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 213, 106501. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Method | DSC | VOE | RAVD | ASSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiTS | HDU-Net [45] | 0.711 | 0.401 | 0.023 | 7.201 |

| ResUNet [46] | 0.705 | 0.395 | 0.534 | 8.286 | |

| MS-FANet [2] | 0.742 | 0.367 | 0.107 | 5.996 | |

| HFRU-Net [47] | 0.749 ± 0.107 | 0.380 ± 0.128 | 0.218 ± 0.152 | - | |

| RMAU-Net [34] | 0.762 ± 0.118 | 0.371 ± 0.135 | 0.012 ± 0.291 | - | |

| The proposed | 0.844 ± 0.078 | 0.263 ± 0.114 | 0.133 ± 0.143 | 1.317 ± 0.645 | |

| 3DIRCADb | HDU-Net | 0.692 | 0.382 | 4.835 | 16.516 |

| ResUNet | 0.739 | 0.357 | 0.102 | 7.817 | |

| MS-FANet | 0.780 | 0.313 | 0.155 | 5.346 | |

| HFRU-Net | 0.789 ± 0.111 | 0.326 ± 0.142 | 0.033 ± 0.170 | - | |

| RMAU-Net | 0.831 ± 0.095 | 0.275 ± 0.125 | 0.126 ± 0.186 | - | |

| The proposed | 0.832 ± 0.060 | 0.283 ± 0.085 | 0.138 ± 0.111 | 1.682 ± 1.029 |

| Dataset | Method | DSC | VOE | RAVD | ASSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiTS | Without post-processing | 0.845 | 0.261 | 0.143 | 1.267 |

| With post-processing | 0.844 | 0.263 | 0.133 | 1.317 | |

| 3DIRCADb | Without post-processing | 0.803 | 0.313 | 0.198 | 1.784 |

| With post-processing | 0.832 | 0.283 | 0.138 | 1.682 |

| Dataset | Dilation Times | DSC | VOE | RAVD | ASSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiTS | 1 | 0.845 | 0.261 | 0.138 | 1.311 |

| 2 | 0.844 | 0.263 | 0.133 | 1.317 | |

| 3 | 0.841 | 0.267 | 0.127 | 1.327 | |

| 3DIRCADb | 1 | 0.827 | 0.291 | 0.164 | 1.712 |

| 2 | 0.832 | 0.283 | 0.138 | 1.682 | |

| 3 | 0.824 | 0.294 | 0.192 | 1.693 |

| Number of Parameters | Floating Point Operations/Second | Training Time/Epoch | Inference Time/CT Scan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiTS Dataset | 3DIRACDb Dataset | |||

| 97.73 M | 73.12 G | 26 min | 176.9 ± 124.8 s | 43.8 ± 12.8 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shin, H.; Han, K.; Lee, S.; Park, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.D.; Song, J.; Yu, H.C.; et al. Deep Learning-Based Liver Tumor Segmentation from Computed Tomography Scans with a Gradient-Enhanced Network. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030429

Shin H, Han K, Lee S, Park H, Kim S, Kim J, Yang X, Yang JD, Song J, Yu HC, et al. Deep Learning-Based Liver Tumor Segmentation from Computed Tomography Scans with a Gradient-Enhanced Network. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(3):429. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030429

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Hangyeul, Kyujin Han, Seungyoo Lee, Harin Park, Seunghyon Kim, Jeonghun Kim, Xiaopeng Yang, Jae Do Yang, Jisoo Song, Hee Chul Yu, and et al. 2026. "Deep Learning-Based Liver Tumor Segmentation from Computed Tomography Scans with a Gradient-Enhanced Network" Diagnostics 16, no. 3: 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030429

APA StyleShin, H., Han, K., Lee, S., Park, H., Kim, S., Kim, J., Yang, X., Yang, J. D., Song, J., Yu, H. C., & You, H. (2026). Deep Learning-Based Liver Tumor Segmentation from Computed Tomography Scans with a Gradient-Enhanced Network. Diagnostics, 16(3), 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030429