Intra-Arterial Radioligand Therapy in Brain Cancer: Bridging Nuclear Medicine and Interventional Neuroradiology

Abstract

1. Introduction

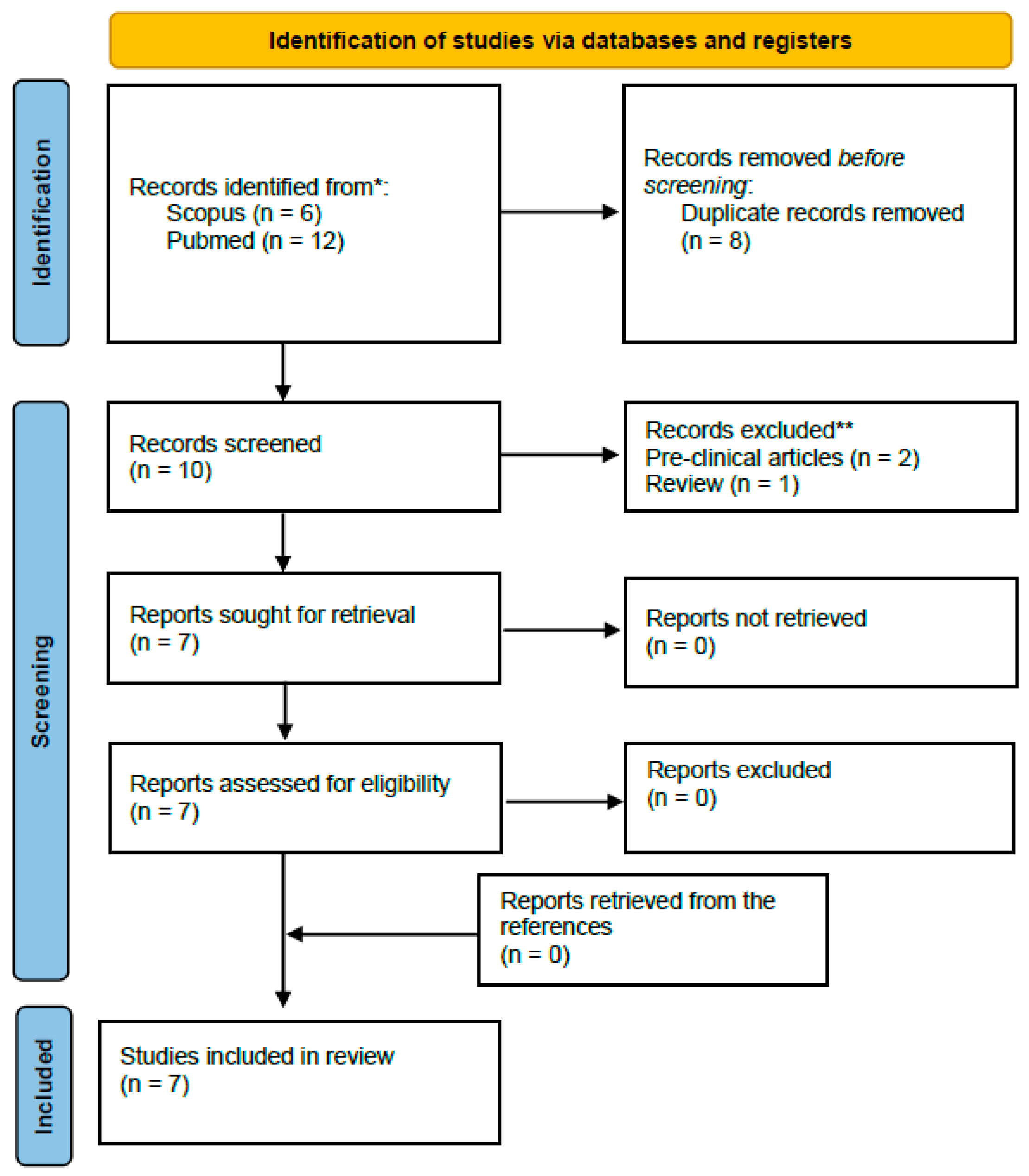

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Intra-Arterial Diagnostic Imaging

3.2. Intra-Arterial Administration for RLT Enrollment and Dosimetric Modeling

3.3. Therapeutic Applications

3.4. Radiotracers in Malignant Brain Tumors, Implications for Radioligand Therapy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RLT | Radioligand therapy |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SSTR | Somatostatin receptor subtype |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| SUV | Standardized uptake value |

| PSMA | Prostate-specific membrane antigen |

| FAP | Fibroblast activation protein |

| FAPI | Fibroblast activation protein inhibitors |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| SD | Stable disease |

| PD | Progression disease |

References

- Modha, A.; Gutin, P.H. Diagnosis and Treatment of Atypical and Anaplastic Meningiomas: A Review. Neurosurgery 2005, 57, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cui, Y.; Zou, L. Treatment Advances in High-Grade Gliomas. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1287725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, D.; Raposa, B.L.; Freihat, O.; Simon, M.; Mekis, N.; Cornacchione, P.; Kovács, Á. Glioblastoma: Clinical Presentation, Multidisciplinary Management, and Long-Term Outcomes. Cancers 2025, 17, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogasawara, C.; Philbrick, B.D.; Adamson, D.C. Meningioma: A Review of Epidemiology, Pathology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Future Directions. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Jiang, K.; Rincon-Torroella, J.; Materi, J.; Azad, T.D.; Kamson, D.O.; Kleinberg, L.R.; Bettegowda, C. Epidemiological Trends, Prognostic Factors, and Survival Outcomes of Synchronous Brain Metastases from 2015 to 2019: A Population-Based Study. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2023, 5, vdad015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbrunner, R.; Stavrinou, P.; Jenkinson, M.D.; Sahm, F.; Mawrin, C.; Weber, D.C.; Preusser, M.; Minniti, G.; Lund-Johansen, M.; Lefranc, F.; et al. EANO Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Meningiomas. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1821–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, M.; Van Den Bent, M.; Preusser, M.; Le Rhun, E.; Tonn, J.C.; Minniti, G.; Bendszus, M.; Balana, C.; Chinot, O.; Dirven, L.; et al. EANO Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diffuse Gliomas of Adulthood. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuzhalin, A.E. New Experimental Therapies for Glioblastoma: A Review of Preclinical Research. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, A.M.; Di, L.; Shah, A.H.; Crespo, R.; Eichberg, D.G.; Lu, V.M.; Luther, E.M.; Komotar, R.J.; Ivan, M.E. Current Experimental Therapies for Atypical and Malignant Meningiomas. J. Neurooncol. 2021, 153, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, J.; Zoetelief, E.; Brabander, T.; de Herder, W.W.; Hofland, J. Current Status of Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in Grade 1 and 2 Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2025, 37, e13469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninatti, G.; Lee, S.T.; Scott, A.M. Radioligand Therapy in Cancer Management: A Global Perspective. Cancers 2025, 17, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farolfi, A.; Fendler, W.; Iravani, A.; Haberkorn, U.; Hicks, R.; Herrmann, K.; Walz, J.; Fanti, S. Theranostics for Advanced Prostate Cancer: Current Indications and Future Developments. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2019, 2, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateishi, U. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA)-Ligand Positron Emission Tomography and Radioligand Therapy (RLT) of Prostate Cancer. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 50, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, L.; Urso, L.; Bianconi, F.; Palumbo, B.; Marzola, M.C.; Evangelista, L.; Schillaci, O. Radiomics and Theranostics with Molecular and Metabolic Probes in Prostate Cancer: Toward a Personalized Approach. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2023, 23, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, B.J.; Bartlett, D.J.; McGarrah, P.W.; Lewis, A.R.; Johnson, D.R.; Berberoğlu, K.; Pandey, M.K.; Packard, A.T.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Hruska, C.B.; et al. A Review of Theranostics: Perspectives on Emerging Approaches and Clinical Advancements. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 2023, 5, e220157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittra, E.S.; Wong, R.K.S.; Winters, C.; Brown, A.; Murley, S.; Kennecke, H. Establishing a Robust Radioligand Therapy Program: A Practical Approach for North American Centers. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e6780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirian, C.; Duun-Henriksen, A.K.; Maier, A.; Pedersen, M.M.; Jensen, L.R.; Bashir, A.; Graillon, T.; Hrachova, M.; Bota, D.; Van Essen, M.; et al. Somatostatin Receptor–Targeted Radiopeptide Therapy in Treatment-Refractory Meningioma: Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwil, C.; López-Benítez, R.; Mier, W.; Haufe, S.; Isermann, B.; Kauczor, H.-U.; Choyke, P.L.; Haberkorn, U.; Giesel, F.L. Hepatic Arterial Infusion Enhances DOTATOC Radiopeptide Therapy in Patients with Neuroendocrine Liver Metastases. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2011, 18, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braat, A.J.A.T.; Snijders, T.J.; Seute, T.; Vonken, E.P.A. Will 177Lu-DOTATATE Treatment Become More Effective in Salvage Meningioma Patients, When Boosting Somatostatin Receptor Saturation? A Promising Case on Intra-Arterial Administration. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2019, 42, 1649–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuijzen Van Zanten, S.E.M.; Bos, E.M.; Verburg, F.A.; Van Doormaal, P.-J. Intracranial Hemangiopericytoma Showing Excellent Uptake on Arterial Injection of [68Ga]DOTATATE. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 1673–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruis, I.J.; Van Doormaal, P.J.; Balvers, R.K.; Van Den Bent, M.J.; Harteveld, A.A.; De Jong, L.C.; Konijnenberg, M.W.; Segbers, M.; Valkema, R.; Verburg, F.A.; et al. Potential of PSMA-Targeting Radioligand Therapy for Malignant Primary and Secondary Brain Tumours Using Super-Selective Intra-Arterial Administration: A Single Centre, Open Label, Non-Randomised Prospective Imaging Study. eBioMedicine 2024, 102, 105068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonken, E.-J.P.A.; Bruijnen, R.C.G.; Snijders, T.J.; Seute, T.; Lam, M.G.E.H.; Keizer, B.D.; Braat, A.J.A.T. Intraarterial Administration Boosts177 Lu-HA-DOTATATE Accumulation in Salvage Meningioma Patients. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 406–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puranik, A.D.; Dev, I.D.; Rangarajan, V.; Kulkarni, S.; Shetty, N.; Gala, K.; Sahu, A.; Bhattacharya, K.; Dasgupta, A.; Chatterjee, A.; et al. PRRT with Lu-177 DOTATATE in Treatment-Refractory Progressive Meningioma: Initial Experience from a Tertiary-Care Neuro-Oncology Center. Neurol. India 2024, 72, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerein, A.; Maurer, C.; Kircher, M.; Gäble, A.; Krebold, A.; Rinscheid, A.; Viering, O.; Pfob, C.H.; Bundschuh, R.A.; Behrens, L.; et al. Intraarterial Administration of Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in Patients with Advanced Meningioma: Initial Safety and Efficacy. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 1911–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghalbouni, A.; Snijders, T.J.; Amerein, A.; Tolboom, N.; Patt, M.; Maurer, C.J.; Van Der Schaaf, I.C.; Lapa, C.; Braat, A.J.A.T. Efficacy of Intra-Arterial [177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE Monotherapy for Treatment-Refractory Meningioma. J. Neurooncol. 2026, 176, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.R.; Flores, B.C.; Ban, V.S.; Hatanpaa, K.J.; Mickey, B.E.; Barnett, S.L. Intracranial Hemangiopericytomas: Recurrence, Metastasis, and Radiotherapy. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 2017, 78, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, T.-J.; Macdonald, W.; Muir, T.; Celliers, L.; Al-Ogaili, Z. 68Ga DOTATATE PET/CT of Non–FDG-Avid Pulmonary Metastatic Hemangiopericytoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2016, 41, 779–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ros, V.; Filippi, L.; Garaci, F. Intra-Arterial Administration of PSMA-Targeted Radiopharmaceuticals for Brain Tumors: Is the Era of Interventional Theranostics Next? Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2024, 24, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwil, C.; Fendler, W.P.; Eiber, M.; Hofman, M.S.; Emmett, L.; Calais, J.; Osborne, J.R.; Iravani, A.; Koo, P.; Lindenberg, L.; et al. Joint EANM/SNMMI Procedure Guideline for the Use of 177Lu-Labeled PSMA-Targeted Radioligand-Therapy (177Lu-PSMA-RLT). Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 50, 2830–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Parihar, A.S.; Bodei, L.; Hope, T.A.; Mallak, N.; Millo, C.; Prasad, K.; Wilson, D.; Zukotynski, K.; Mittra, E. Somatostatin Receptor Imaging and Theranostics: Current Practice and Future Prospects. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaknun, J.J.; Bodei, L.; Mueller-Brand, J.; Pavel, M.E.; Baum, R.P.; Hörsch, D.; O’Dorisio, M.S.; O’Dorisiol, T.M.; Howe, J.R.; Cremonesi, M.; et al. The Joint IAEA, EANM, and SNMMI Practical Guidance on Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy (PRRNT) in Neuroendocrine Tumours. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2013, 40, 800–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, L.; Valentini, F.B.; Gossetti, B.; Gossetti, F.; De Vincentis, G.; Scopinaro, F.; Massa, R. Intraoperative Gamma Probe Detection of Head and Neck Paragangliomas with 111 In-Pentetreotide: A Pilot Study. Tumori 2005, 91, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, L.; Palumbo, I.; Bagni, O.; Schillaci, O.; Aristei, C.; Palumbo, B. Somatostatin Receptor Targeted PET-Imaging for Diagnosis, Radiotherapy Planning and Theranostics of Meningiomas: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; ArunRaj, S.T.; Bhullar, K.; Haresh, K.P.; Gupta, S.; Ballal, S.; Yadav, M.; Singh, M.; Damle, N.A.; Garg, A.; et al. Ga-68 PSMA PET/CT in Recurrent High-Grade Gliomas: Evaluating PSMA Expression in Vivo. Neuroradiology 2022, 64, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasikumar, A.; Joy, A.; Pillai, M.R.A.; Nanabala, R.; Anees K, M.; Jayaprakash, P.G.; Madhavan, J.; Nair, S. Diagnostic Value of 68Ga PSMA-11 PET/CT Imaging of Brain Tumors—Preliminary Analysis. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 42, e41–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graef, J.; Bluemel, S.; Brenner, W.; Amthauer, H.; Truckenmueller, P.; Kaul, D.; Vajkoczy, P.; Onken, J.S.; Furth, C. [177 Lu]Lu-PSMA Therapy as an Individual Treatment Approach for Patients with High-Grade Glioma: Dosimetry Results and Critical Statement. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenhout, C.; Deprez, L.; Hustinx, R.; Withofs, N. Brain Tumor Assessment. PET Clin. 2025, 20, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrich, M.; Loktev, A.; Wefers, A.K.; Altmann, A.; Paech, D.; Adeberg, S.; Windisch, P.; Hielscher, T.; Flechsig, P.; Floca, R.; et al. IDH-Wildtype Glioblastomas and Grade III/IV IDH-Mutant Gliomas Show Elevated Tracer Uptake in Fibroblast Activation Protein–Specific PET/CT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 2569–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, C.; Kessler, L.; Blau, T.; Keyvani, K.; Pabst, K.M.; Fendler, W.P.; Fragoso Costa, P.; Lazaridis, L.; Schmidt, T.; Feldheim, J.; et al. The Role of Fibroblast Activation Protein in Glioblastoma and Gliosarcoma: A Comparison of Tissue,68 Ga-FAPI-46 PET Data, and Survival Data. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, H.; Cao, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Z. [68Ga]Ga-FAPI PET/CT in Brain Tumors: Comparison with [18F]F-FDG PET/CT. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1436009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighi, C.; Puttick, S.; Woods, A.; Keall, P.; Tooney, P.A.; Waddington, D.E.J.; Sproule, V.; Rose, S.; Fay, M. Comparison between [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-617 and [18F]FET PET as Imaging Biomarkers in Adult Recurrent Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, R.P.; Fan, X.; Jakobsson, V.; Yu, F.; Schuchardt, C.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J. Long-Term Nephrotoxicity after PRRT: Myth or Reality. Theranostics 2024, 14, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ros, V.; Oddo, L.; Toumia, Y.; Guida, E.; Minosse, S.; Strigari, L.; Strolin, S.; Paolani, G.; Di Giuliano, F.; Floris, R.; et al. PVA-Microbubbles as a Radioembolization Platform: Formulation and the In Vitro Proof of Concept. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolani, G.; Minosse, S.; Strolin, S.; Santoro, M.; Pucci, N.; Di Giuliano, F.; Garaci, F.; Oddo, L.; Toumia, Y.; Guida, E.; et al. Intra-Arterial Super-Selective Delivery of Yttrium-90 for the Treatment of Recurrent Glioblastoma: In Silico Proof of Concept with Feasibility and Safety Analysis. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, L.; Di Costanzo, G.G.; Tortora, R.; Pelle, G.; Saltarelli, A.; Marino Marsilia, G.; Cianni, R.; Schillaci, O.; Bagni, O. Prognostic Value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Its Correlation with Fluorine-18-Fluorodeoxyglucose Metabolic Parameters in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Submitted to 90Y-Radioembolization. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2020, 41, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Year)/Country | Study Type | Tumor Type; n | Tracer/Therapeutic Agent | Key Quantitative Uptake Metrics (IA vs. IV) | Median Follow-Up | Main Outcomes | Notable AEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

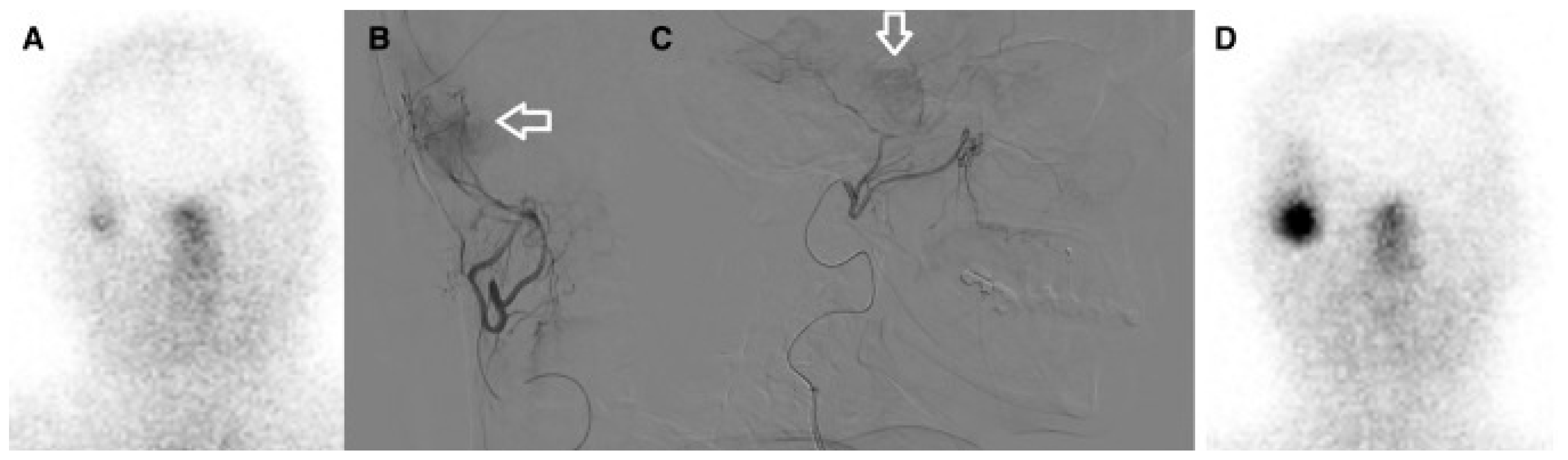

| Braat et al., 2019 [19]/The Netherlands | Case report | Recurrent right-temporal meningioma (WHO II); n = 1 (54 y, F) | 177Lu-DOTATATE (IV then IA) | IV absorbed dose ≈ 4.6 Gy vs. IA ≈ 51 Gy per cycle; ~11× uptake increase | 10 months (single patient) | Partial radiologic response (38% volume reduction), 79% decrease in SSTR2 expression on PET; clinical seizure control | No relevant treatment-related toxicity reported |

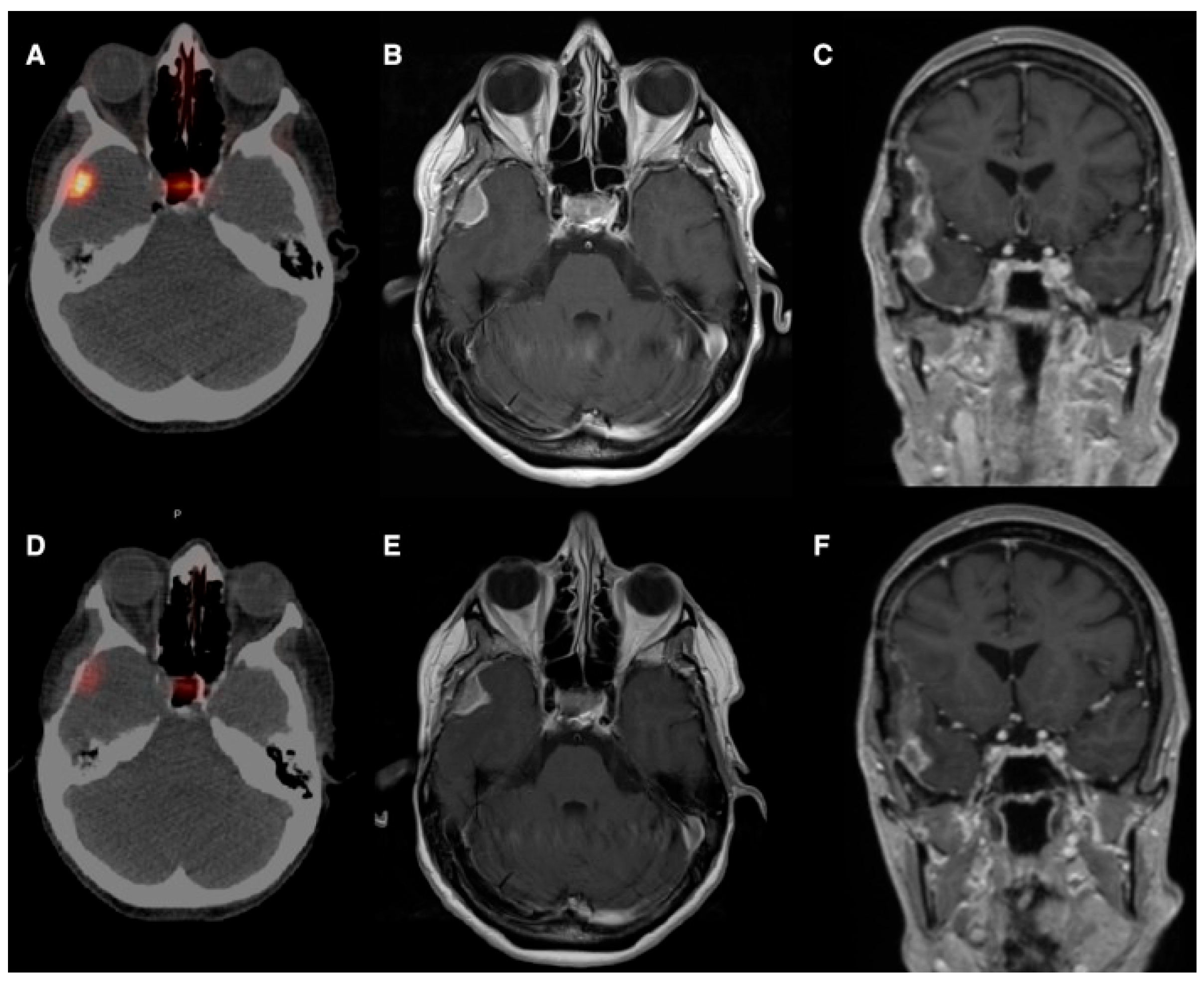

| Veldhuijzen Van Zanten et al., 2021 [20]/The Netherlands | Case report/ 40-year-old | Intracranial hemangiopericytoma; n = 1 (40, F) | 68Ga-DOTATATE (arterial injection) | Doubling of maximum SUV (IA vs. IV) | Not reported (early clinical deterioration; no IA therapy performed) | Selective IA administration increased tumor uptake (SUV_mean: 8.4 → 21.0; SUV_max: 15.8 → 36.0), suggesting potential feasibility of PRRT | Not applicable/not reported |

| Pruis et al., 2024 [21]/The Netherlands | Single-center, open-label, non-randomized prospective imaging study/ | Glioblastoma (IDH-wt) n = 4; oligodendroglioma n = 1; brain mets (NSCLC n = 4, breast n = 1); total n = 10 (8 M) | 68Ga-PSMA-11 (IA vs. IV diagnostic imaging; median IA activity ≈ 82 MBq) | Median ~15× higher tumor uptake after IA vs. IV (semi-quantitative analysis); imaging acquired 90, 165, 240 min post-injection | Imaging-only study: short-term imaging up to 240 min p.i. (no long-term median follow-up reported) | IA increases tumor uptake enabling dosimetric modeling for 177Lu- or 225Ac-based RLT; all patients qualified for IA RLT based on IA imaging | One transient stroke-like syndrome (probable vascular spasm/contrast encephalopathy); otherwise well tolerated |

| Vonken et al., 2022 [22]/The Netherlands | Retrospective intrapatient comparison (selected patients) | Salvage meningioma patients; n = 4 IA-treated (selected from 7 referred), age: 44–66 y | 177Lu-HA-DOTATATE (IV then IA) | Planar target-to-background ratio median: 1.7 (IV) → 3.7 (IA); SPECT/CT ratio: 15.0 (IV) → 59.8 (IA) | Median follow-up 1.7 y | IA PRRT feasible and safe; 3 patients completed 4 cycles (1 PR, 2 SD); 1 WHO grade 3 patient progressed and died | One isolated grade 3 leukopenia; no angiography-related complications reported |

| Puranik et al., 2024 [23]/India | Single-center initial experience/case series | Treatment-refractory progressive meningioma (WHO I–III); n = 8 (5 M), median age: median age–52.3 t | 177Lu-DOTATATE PRRT (IV cycle for systemic coverage; subsequent IA cycles in 4 patients); 7.4 GBq per cycle | Mean tumor absorbed dose: 2.86 Gy (IV) → 3.62 Gy (IA); absorbed dose per unit activity: 0.82 Gy/GBq (IV) → 1.72 Gy/GBq (IA) | Median time to progression 8.9 months (study reports this efficacy timeframe) | Majority with stable disease or partial response after two cycles; metabolic PET response correlated with MRI; symptomatic improvement reported | No significant PRRT-related or angiography-related toxicities; no grade ≥3 non-hematologic AEs reported |

| Amerein et al., 2024 [24]/Germany | Single-center retrospective series | Progressive, advanced meningioma (SSTR-positive); n = 13 (8 F); mean age: 65 ± 13 y | 177Lu-HA-DOTATATE IA; per-cycle activity ≈ 6.0–7.7 GBq (mean ≈ 7.4 GBq); up to 4 cycles; mean cumulative ≈ 25.7 GBq | Angiography was successful in all cases (100%). A mean activity of 7.4 GBq per cycle administered without dose reductions, resulting in a mean cumulative activity of 25.7 GBq. | Median progression-free survival reported ≈ 18 months | High rate of disease control (CR/PR/SD in majority); clinical symptom stabilization/improvement; IA PRRT feasible with promising activity | Predominantly transient hematologic toxicity (notably lymphocytopenia); infrequent grade ≥3 AEs; no clear chronic nephrotoxicity; rare angiography-related complications |

| El Ghalbouni et al. [25]/The Netherlands | Retrospective multicenter cohort | Treatment-refractory meningioma (WHO 1–3); n = 17 (11 M), median age: 64 y | 177Lu-DOTATATE monotherapy (selective IA administration); median cycles ≈ 3; median cumulative activity ≈ 28.8 GBq | Study emphasizes IA increased tumor absorbed dose by exploiting first-pass arterial delivery | Median follow-up 36 months | 6-month PFS 65%; OS 82%; objective response rate 24%; disease control rate 53% (RANO criteria); favorable vs. historical IV benchmarks | Limited grade 3 toxicity (mainly anemia); rare radionecrosis or SMART syndrome (likely related to prior radiotherapy); one angiography-related peripheral embolic complication |

| Domain | Items to Report |

|---|---|

| Patient selection | Histology (WHO grade), prior treatments, performance status, PET/SPECT selection thresholds (SUV, ratios), renal function |

| Radiopharmaceutical | Tracer name, radionuclide (e.g., 177Lu, 225Ac, 90Y), specific activity, mass dose |

| Administration technique | Access route (femoral/radial), catheter type, super-selective vessel(s) catheterized, angiographic mapping images, infusion rate, total activity administered |

| Imaging and dosimetry | Pre-IA and post-IA PET protocol (timing, scanner), quantitative metrics (SUVmax, SUVmean, tumor/background ratios), absorbed dose estimates to tumor and organs at risk |

| Safety and AEs | Peri-procedural complications (neurological, vascular), systemic toxicity (renal, salivary gland), grade per CTCAE, time to onset |

| Outcomes and follow-up | Radiologic response criteria (RANO or RECIST as applicable), clinical symptom changes, PFS/OS if available, planned follow-up schedule |

| Translational correlates | If available, paired biopsy data, immunohistochemistry (PSMA, SSTR2a, FAP), microregional uptake correlation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sabuzi, F.; Filippi, L.; Trulli, M.; Domenici, F.; Garaci, F.; Da Ros, V. Intra-Arterial Radioligand Therapy in Brain Cancer: Bridging Nuclear Medicine and Interventional Neuroradiology. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020341

Sabuzi F, Filippi L, Trulli M, Domenici F, Garaci F, Da Ros V. Intra-Arterial Radioligand Therapy in Brain Cancer: Bridging Nuclear Medicine and Interventional Neuroradiology. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020341

Chicago/Turabian StyleSabuzi, Federico, Luca Filippi, Mariafrancesca Trulli, Fabio Domenici, Francesco Garaci, and Valerio Da Ros. 2026. "Intra-Arterial Radioligand Therapy in Brain Cancer: Bridging Nuclear Medicine and Interventional Neuroradiology" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020341

APA StyleSabuzi, F., Filippi, L., Trulli, M., Domenici, F., Garaci, F., & Da Ros, V. (2026). Intra-Arterial Radioligand Therapy in Brain Cancer: Bridging Nuclear Medicine and Interventional Neuroradiology. Diagnostics, 16(2), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020341