Faster Diagnosis of Suspected Lower Respiratory Tract Infections: Single-Center Evidence from BIOFIRE FilmArray® Pneumonia Panel Results vs. Conventional Culture Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Specimen Collection

2.2. BIOFIRE FilmArray® Pneumonia Panel

2.3. Conventional Culture (CC) Method

2.4. Additional Tests for Resistance Markers on Isolated Bacterial Strains

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Specimen Characteristics

3.2. Pathogens Detected with PN Panel and CC Method

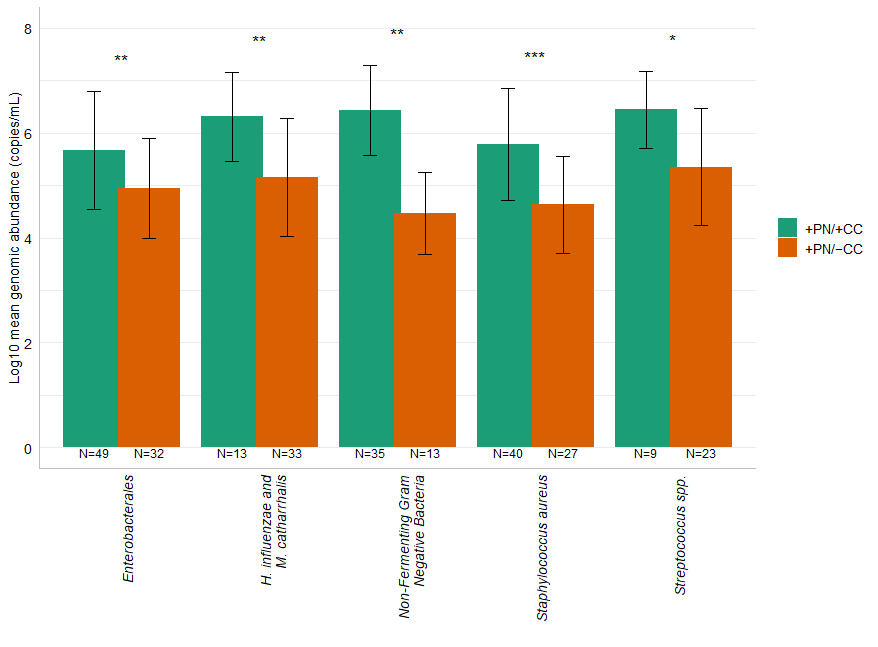

3.3. Comparison of Bacteria Detected by PN Panel Versus CC Method

3.4. Resistance Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LRTIs | Low Respiratory Tract Infections |

| PN | BIOFIRE FilmArray® Pneumonia |

| CC | Conventional Culture |

| AST | Antimicrobial susceptibility Test |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar Lavage |

| LAMP | Loop-mediated isothermal Amplification |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| NA | Not Applicable |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). The Top 10 Causes of Death. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Estimates 2021: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2021. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Kosai, K.; Akamatsu, N.; Ota, K.; Mitsumoto-Kaseida, F.; Sakamoto, K.; Hasegawa, H.; Izumikawa, K.; Mukae, H.; Yanagihara, K. BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel enhances detection of pathogens and antimicrobial resistance in lower respiratory tract specimens. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2022, 21, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchan, B.W.; Windham, S.; Balada-Llasat, J.M.; Leber, A.; Harrington, A.; Relich, R.; Murphy, C.; Bard, J.D.; Naccache, S.; Ronen, S.; et al. Practical comparison of the BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel to routine diagnostic methods and potential impact on antimicrobial stewardship in adult hospitalized patients with lower respiratory tract infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00135-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, G.; He, Y.; Sun, R. Evaluation and clinical practice of pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes of BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel in lower respiratory tract infections. Infection 2024, 52, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuti, E.L.; Patel, A.A.; Coleman, C.I. Impact of inappropriate antibiotic therapy on mortality in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia and bloodstream infection: A meta-analysis. J. Crit. Care 2008, 23, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderaro, A.; Buttrini, M.; Farina, B.; Montecchini, S.; De Conto, F.; Chezzi, C. Respiratory tract infections and laboratory diagnostic methods: A review with a focus on syndromic panel-based assays. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzada, F.M.; Mestre, B.; Vaquer, A.; Tejada, S.; de la Rica, R. Detecting respiratory pathogens for diagnosing lower respiratory tract infections at the point of care: Challenges and opportunities. Biosensors 2025, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leland, D.S.; Ginocchio, C.C. Role of cell culture for virus detection in the age of technology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, M.R.; Bard, J.D. Direct-from-specimen pathogen identification: Evolution of syndromic panels. Clin. Lab. Med. 2019, 39, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bioMérieux. BIOFIRE® FILMARRAY® Pneumonia Panel Operator Manual. 2023. Available online: https://www.biomerieux.com/content/dam/biomerieux-com/service-support/support-documents/instructions-for-use-and-manuals/RFIT-PRT-0575-FilmArray-Pneumo-Instructions-for-Use-EN.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Gastli, N.; Loubinoux, J.; Daragon, M.; Lavigne, J.P.; Saint-Sardos, P.; Pailhoriès, H.; Lemarié, C.; Benmansour, H.; D’hUmières, C.; Broutin, L.; et al. Multicentric evaluation of BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel for rapid bacteriological documentation of pneumonia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharioudakis, I.M.; Zervou, F.N.; Dubrovskaya, Y.; Inglima, K.; See, B.; Aguero-Rosenfeld, M. Evaluation of a multiplex PCR panel for the microbiological diagnosis of pneumonia in hospitalized patients: Experience from an academic medical center. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serigstad, S.; Markussen, D.; Grewal, H.M.S.; Ebbesen, M.; Kommedal, Ø.; Heggelund, L.; van Werkhoven, C.H.; Faurholt-Jepsen, D.; Clark, T.W.; Ritz, C.; et al. Rapid syndromic PCR testing in patients with respiratory tract infections reduces time to results and improves microbial yield. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, D.M.; Wallace, M.A.; Burnham, C.A.; Anderson, N.W. Evaluation of the BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel for detection of viral and bacterial pathogens in lower respiratory tract specimens in the setting of a tertiary care academic medical center. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00343-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytter, H.; Jamet, A.; Coureuil, M.; Charbit, A.; Ramond, E. Which current and novel diagnostic avenues for bacterial respiratory diseases? Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 616971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croxatto, A.; Prod’hom, G.; Greub, G. Applications of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in clinical diagnostic microbiology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalieri, S.J.; Kwon, S.; Vivekanandan, R.; Ased, S.; Carroll, C.; Anthone, J.; Schmidt, D.; Baysden, M.; Destache, C.J. Effect of antimicrobial stewardship with rapid MALDI-TOF identification and Vitek 2 antimicrobial susceptibility testing on hospitalization outcome. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 95, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Clinical Breakpoint Tables. (v 15.0). 2025. Available online. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_15.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Bernabeu, S.; Ratnam, K.C.; Boutal, H.; Gonzalez, C.; Vogel, A.; Devilliers, K.; Plaisance, M.; Oueslati, S.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Dortet, L.; et al. A Lateral Flow Immunoassay for the Rapid Identification of CTX-M-Producing Enterobacterales from Culture Plates and Positive Blood Cultures. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jia, P.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Duan, S.; Kang, W.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Q. Carbapenemase detection by NG-Test CARBA 5-a rapid immunochromatographic assay in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales diagnosis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa Hellou, M.; Virk, A.; Strasburg, A.P.; Harmsen, W.S.; Vergidis, P.; Kooda, K.; Kies, K.D.; Donadio, A.D.; Mandrekar, J.; Schuetz, A.N.; et al. Performance of BIOFIRE FILMARRAY Pneumonia Panel in suspected pneumonia: Insights from a real-world study. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0057125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Ruan, S.Y.; Pan, S.C.; Lee, T.F.; Chien, J.Y.; Hsueh, P.R. Performance of a multiplex PCR pneumonia panel for the identification of respiratory pathogens and the main determinants of resistance from the lower respiratory tract specimens of adult patients in intensive care units. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsey, A.R.; Branche, A.R.; Croft, D.P.; Formica, M.A.; Peasley, M.R.; Walsh, E.E. Real-life assessment of BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel in adults hospitalized with respiratory illness. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 229, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Babushkin, F.; Finn, T.; Geller, K.; Alexander, H.; Datnow, C.; Uda, M.; Shapiro, M.; Paikin, S.; Lellouche, J. High rates of bacterial pulmonary co-infections and superinfections identified by multiplex PCR among critically ill COVID-19 patients. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søgaard, K.K.; Hinic, V.; Goldenberger, D.; Gensch, A.; Schweitzer, M.; Bättig, V.; Siegemund, M.; Bassetti, S.; Bingisser, R.; Tamm, M.; et al. Evaluation of the clinical relevance of the BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel among hospitalized patients. Infection 2024, 52, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, K.H.; Beal, S.G.; Cherabuddi, K.; Couturier, B.; Lingenfelter, B.; Rindlisbacher, C.; Jones, J.; Houck, H.J.; Lessard, K.J.; E Tremblay, E. Performance of a semiquantitative multiplex bacterial and viral PCR panel compared with standard microbiological laboratory results: 396 patients studied with the BioFire Pneumonia Panel. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 8, ofaa560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitmuang, A.; Puttinad, S.; Hemvimol, S.; Pansasiri, S.; Horthongkham, N. A multiplex pneumonia panel for diagnosis of hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia in the era of emerging antimicrobial resistance. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 977320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafylaki, D.; Maraki, S.; Vaporidi, K.; Georgopoulos, D.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Kofteridis, D.P.; Chamilos, G. Impact of molecular syndromic diagnosis of severe pneumonia in the management of critically ill patients. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0161622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Fuentes, C.A.; Reyes-Montes, M.D.R.; Frías-De-León, M.G.; Valencia-Ledezma, O.E.; Acosta-Altamirano, G.; Duarte-Escalante, E. Aspergillus–SARS-CoV-2 coinfection: What is known? Pathogens 2022, 11, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.N.; Fowler, R.; Balada-Llasat, J.M.; Carroll, A.; Stone, H.; Akerele, O.; Buchan, B.; Windham, S.; Hopp, A.; Ronen, S.; et al. Multicenter evaluation of the BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia/Pneumonia Plus Panel for detection and quantification of agents of lower respiratory tract infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00128-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, K.H.; Beal, S.G.; Cherabuddi, K.; Houck, H.; Lessard, K.; Tremblay, E.E.; Couturier, B.; Lingenfelter, B.; Rindlisbacher, C.; Jones, J. Relationship of multiplex molecular pneumonia panel results with hospital outcomes and clinical variables. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, N.A.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Aboshanab, K.M.; El Borhamy, M.I. Evaluation of the BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel Plus compared to conventional diagnostic methods in determining the microbiological etiology of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Biology 2022, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolyi, M.; Pawelka, E.; Hind, J.; Baumgartner, S.; Friese, E.; Hoepler, W.; Neuhold, S.; Omid, S.; Seitz, T.; Traugott, M.T.; et al. Detection of bacteria via multiplex PCR in respiratory samples of critically ill COVID-19 patients with suspected HAP/VAP in the ICU. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr 2022, 134, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschi, C.; Zignoli, A.; Gaibani, P.; Vocale, C.; Rossini, G.; Lafratta, S.; Liberatore, A.; Turello, G.; Lazzarotto, T.; Ambretti, S. Respiratory bacterial co-infections in intensive care unit-hospitalized COVID-19 patients: Conventional culture vs BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Plus Panel. J. Microbiol. Methods 2021, 186, 106259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics and Critical Care Units | Overall | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | p -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (N) | 343 | 94 | 110 | 139 | |

| Males (N, %) | 238 (69.4) | 67 (71.3) | 80 (72.7) | 91 (65.5) | 0.42 * |

| Age (year, median) | 60 (48–68) | 63 (52–69) | 57 (46–68) | 60 (46–68) | 0.25 ** |

| Specimens (N) | 410 | 115 | 133 | 162 | |

| Hematology (N, %) | 31 (7.6) | 13 (11.3) | 7 (5.3) | 11 (6.8) | 0.06 * |

| Intensive care (N, %) | 245 (59.8) | 75 (65.2) | 81 (60.9) | 89 (54.9) | |

| Medicine (N, %) | 115 (28.0) | 26 (22.6) | 36 (27.1) | 53 (32.7) | |

| Surgery (N, %) | 19 (4.6) | 1 (0.9) | 9 (6.7) | 9 (5.6) |

| Targets | PN Panel N (%) |

|---|---|

| Bacteria | |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex | 9 (2.20) |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | 10 (2.44) |

| Escherichia coli | 28 (6.83) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 42 (10.24) |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 4 (0.98) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 5 (1.22) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae group | 20 (4.88) |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 4 (0.98) |

| Proteus spp. | 6 (1.46) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 39 (9.51) |

| Serratia marcescens | 8 (1.95) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 67 (16.34) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 2 (0.49) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 25 (6.10) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 5 (1.22) |

| Atypical bacteria | |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | 1 (0.24) |

| Legionella pneumophila | 5 (1.22) |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 4 (0.98) |

| Viruses | |

| Adenovirus | 4 (0.98) |

| Coronavirus (229E, OC43, HKU1, NL63) | 12 (2.93) |

| Influenza Virus A | 21 (5.12) |

| Influenza Virus B | 0 (0.00) |

| MERS-CoV | 0 (0.00) |

| Metapneumovirus | 8 (1.95) |

| Parainfluenza Virus | 5 (1.22) |

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | 4 (0.98) |

| Total samples | 221 (54) |

| Culture N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Pathogens included in PN panel | |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex | 8 (1.95) |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | 7 (1.71) |

| Escherichia coli | 19 (4.63) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 11 (2.68) |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 2 (0.49) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 2 (0.49) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae group | 20 (4.88) |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 2 (0.49) |

| Proteus spp. | 5 (1.22) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 35 (8.54) |

| Serratia marcescens | 4 (0.98) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 40 (9.76) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 0 (0.00) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 9 (2.20) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 0 (0.00) |

| Pathogens not included in PN panel | |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 (0.24) |

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans | 1 (0.24) |

| Burkholderia cepacia group | 1 (0.24) |

| Citrobacter koseri | 3 (0.73) |

| Morganella morganii | 1 (0.24) |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 8 (1.95) |

| Total samples | 138 (33.9) |

| Bacteria | Sensibility (%, CI) | Specificity (%, CI) | Accuracy (%, CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex | 87.5 (47.35–99.68) | 99.5 (98.21–99.94) | 99.27 (97.88–99.85) |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | 57.14 (18.41–90.10) | 98.51 (96.79–99.45) | 97.8 (95.87–98.99) |

| Escherichia coli | 89.47 (66.86–98.70) | 97.19 (95.02–98.59) | 96.83 (94.64–98.30) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 100 (71.51–100.00) | 92.23 (89.15–94.66) | 92.44 (89.44–94.81) |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 100 (15.81–100.00) | 99.51 (98.24–99.94) | 99.51 (98.25–99.94) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 100 (15.81–100.00) | 99.26 (97.87–99.85) | 99.27 (97.88–99.85) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae group | 75 (50.90–91.34) | 98.72 (97.03–99.58) | 97.56 (95.56–98.82) |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 100 (15.81–100.00) | 99.51 (98.24–99.94) | 99.51 (98.25–99.94) |

| Proteus spp. | 100 (47.82–100.00) | 99.75 (98.63–99.99) | 99.76 (98.65–99.99) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 80 (63.06–91.56) | 97.07 (94.81–98.53) | 95.61 (93.15–97.38) |

| Serratia marcescens | 100 (39.76–100.00) | 99.01 (97.50–99.73) | 99.02 (97.52–99.73) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 100 (91.19–100.00) | 92.7 (89.56–95.14) | 93.41 (90.56–95.62) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | NA * | 99.51 (98.25–99.94) | NA * |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 100 (66.37–100.00) | 96.01 (93.60–97.70) | 96.1 (93.74–97.75) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | NA * | 98.78 (97.18–99.60) | NA * |

| Total | 89.02 (83.21–93.36) | 97.86 (97.46–98.21) | 97.63 (97.21–97.99) |

| Bacteria | +PN/+CC | −PN/−CC | +PN/−CC | −PN/+CC | PPV * (%, CI) | NPV * (%, CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex | 7 | 400 | 2 | 1 | 77.8 (46.15–93.46) | 99.8 (98.46–99.96) |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | 4 | 397 | 6 | 3 | 40 (19.37–64.92) | 99.3 (98.25–99.68) |

| Escherichia coli | 17 | 380 | 11 | 2 | 60.7 (45.83–73.85) | 99.5 (98.08–99.96) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 11 | 368 | 31 | 0 | 26.2 (20.19–33.23) | 100 (99.00–100) |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | 2 | 406 | 2 | 0 | 50 (20.06–79.94) | 100 (99.10–100) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 2 | 405 | 3 | 0 | 40 (17.76–67.30) | 100 (99.09–100) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae group | 15 | 385 | 5 | 5 | 75 (54.78–88.14) | 98.7 (97.30–99.40) |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 2 | 406 | 2 | 0 | 50 (20.06–79.94) | 100 (99.10–100) |

| Proteus spp. | 5 | 404 | 1 | 0 | 83.3 (41.38–97.25) | 100 (99.09–100) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 28 | 364 | 11 | 7 | 71.8 (58.15–82.34) | 98.1 (96.40–99.02) |

| Serratia marcescens | 4 | 402 | 4 | 0 | 50 (27.39–72.61) | 100 (99.09–100) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 40 | 343 | 27 | 0 | 59.7 (50.75–68.05) | 100 (98.93–100) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 0 | 408 | 2 | 0 | NA ** | 100 (99.10–100) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 9 | 385 | 16 | 0 | 36 (25.81–47.63) | 100 (99.09–100) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 0 | 405 | 5 | 0 | NA ** | 98.78 (97.18–99.60) |

| Total | 146 | 5858 | 128 | 18 | 89.02 (83.21–93.36) | 97.86 (97.46–98.21) |

| Genomic Abundance (Low [<106]) (High [≥106]) | No Growth in Culture (N, %) | Low Growth in Culture ([<105]) (N, %) | High Growth in Culture ([≥105]) (N, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Low (N = 39) | 23 (58.97) | 14 (35.90) | 2 (5.13) |

| High (N =28) | 4 (14.29) | 10 (35.71) | 14 (50.00) | |

| Streptococcus spp. * | Low (N = 13) | 12 (92.31) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.69) |

| High (N = 19) | 11 (57.89) | 1 (5.26) | 7 (36.85) | |

| Enterobacterales | Low (N = 46) | 25 (54.37) | 17 (36.96) | 4 (8.69) |

| High (N = 35) | 7 (20.00) | 8 (22.86) | 20 (57.14) | |

| Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Bacteria ** | Low (N = 17) | 11 (64.71) | 6 (35.29) | 0 (0.0) |

| High (N = 31) | 2 (6.45) | 6 (19.36) | 23 (74.19) | |

| Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis | Low (N = 23) | 20 (86.95) | 2 (8.70) | 1 (4.35) |

| High (N = 23) | 13 (56.52) | 2 (8.70) | 8 (34.78) |

| +PN/−CC | +PN/−CC | −PN/+CC | −PN/−CC | PPV * (%, CI) | NPV * (%, CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbapenemase | 3 | 1 | 0 | 38 | 75 (30.24–95.41) | 100.00 (90.75–100.00) |

| CTX-M | 10 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 90.91 (59.30–98.56) | 95.65 (77.21–99.30) |

| mecA/C and MREJ | 9 | 3 | 0 | 28 | 75 (50.58–89.79) | 100.00 (87.66–100.00) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Orena, B.S.; Cariani, L.; Tomassini, E.; Girardi, F.; D’Accico, M.; Pirrone, A.; Biassoni, C.; Girelli, D.; Teri, A.; Tonelli, M.; et al. Faster Diagnosis of Suspected Lower Respiratory Tract Infections: Single-Center Evidence from BIOFIRE FilmArray® Pneumonia Panel Results vs. Conventional Culture Method. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020342

Orena BS, Cariani L, Tomassini E, Girardi F, D’Accico M, Pirrone A, Biassoni C, Girelli D, Teri A, Tonelli M, et al. Faster Diagnosis of Suspected Lower Respiratory Tract Infections: Single-Center Evidence from BIOFIRE FilmArray® Pneumonia Panel Results vs. Conventional Culture Method. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(2):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020342

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrena, Beatrice Silvia, Lisa Cariani, Elena Tomassini, Filippo Girardi, Monica D’Accico, Alessia Pirrone, Caterina Biassoni, Daniela Girelli, Antonio Teri, Marco Tonelli, and et al. 2026. "Faster Diagnosis of Suspected Lower Respiratory Tract Infections: Single-Center Evidence from BIOFIRE FilmArray® Pneumonia Panel Results vs. Conventional Culture Method" Diagnostics 16, no. 2: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020342

APA StyleOrena, B. S., Cariani, L., Tomassini, E., Girardi, F., D’Accico, M., Pirrone, A., Biassoni, C., Girelli, D., Teri, A., Tonelli, M., Alteri, C., & Callegaro, A. (2026). Faster Diagnosis of Suspected Lower Respiratory Tract Infections: Single-Center Evidence from BIOFIRE FilmArray® Pneumonia Panel Results vs. Conventional Culture Method. Diagnostics, 16(2), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16020342